From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Euro| see also § euro in various languages |

|---|

|

|

| Code | EUR (numeric: 978) |

|---|

| Subunit | 0.01 |

|---|

|

| Unit | euro |

|---|

| Plural | Varies, see language and the euro |

|---|

| Symbol | € |

|---|

| Nickname | The single currency |

|---|

|

| Subunit |

|

|---|

| 1⁄100 | cent

(Name varies by language) |

|---|

| Plural |

|

|---|

| cent | (Varies by language) |

|---|

| Symbol |

|

|---|

| cent | c |

|---|

| Banknotes |

|

|---|

| Freq. used | €5, €10, €20, €50, €100 |

|---|

| Rarely used | €200, €500 |

|---|

| Coins |

|

|---|

| Freq. used | 1c, 2c, 5c, 10c, 20c, 50c, €1, €2 |

|---|

| Rarely used | 1c, 2c (Belgium, Finland, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands) |

|---|

|

| User(s) | primary: § members of Eurozone (20),

also: § other users |

|---|

|

| Central bank | Eurosystem |

|---|

| Website | www.ecb.europa.eu |

|---|

| Printer | see § Banknote printing |

|---|

| Mint | see § Coin minting |

|---|

|

| Inflation | 8.6% (June 2022) |

|---|

| Source | ec.europa.eu |

|---|

| Method | HICP |

|---|

| Pegged by | see § Pegged currencies |

|---|

Euro

Monetary policy Euro Zone inflation year/year

M3 money supply increases

Marginal Lending Facility

Main Refinancing Operations

Deposit Facility Rate

The euro (symbol: €; code: EUR) is the official currency of 20 of the 27 member states of the European Union (EU). This group of states is known as the eurozone or, officially, the euro area, and includes about 344 million citizens as of 2023. The euro is divided into 100 cents.

The currency is also used officially by the institutions of the European Union, by four European microstates that are not EU members, the British Overseas Territory of Akrotiri and Dhekelia, as well as unilaterally by Montenegro and Kosovo. Outside Europe, a number of special territories of EU members also use the euro as their currency. Additionally, over 200 million people worldwide use currencies pegged to the euro.

The euro is the second-largest reserve currency as well as the second-most traded currency in the world after the United States dollar. As of December 2019,

with more than €1.3 trillion in circulation, the euro has one of the

highest combined values of banknotes and coins in circulation in the

world.

The name euro was officially adopted on 16 December 1995 in Madrid. The euro was introduced to world financial markets as an accounting currency on 1 January 1999, replacing the former European Currency Unit

(ECU) at a ratio of 1:1 (US$1.1743). Physical euro coins and banknotes

entered into circulation on 1 January 2002, making it the day-to-day

operating currency of its original members, and by March 2002 it had

completely replaced the former currencies.

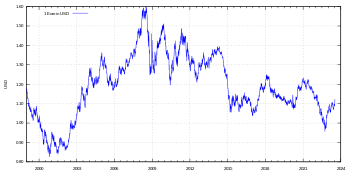

Between December 1999 and December 2002, the euro traded below

the US dollar, but has since traded near parity with or above the US

dollar, peaking at US$1.60 on 18 July 2008 and since then returning near

to its original issue rate. On 13 July 2022, the two currencies hit

parity for the first time in nearly two decades due in part to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Characteristics

Administration

The euro is managed and administered by the European Central Bank (ECB, Frankfurt am Main) and the Eurosystem (composed of the central banks of the eurozone countries). As an independent central bank, the ECB has sole authority to set monetary policy. The Eurosystem participates in the printing, minting and distribution of notes and coins in all member states, and the operation of the eurozone payment systems.

The 1992 Maastricht Treaty obliges most EU member states to adopt the euro upon meeting certain monetary and budgetary convergence criteria, although not all participating states have done so. Denmark has negotiated exemptions, while Sweden (which joined the EU in 1995, after the Maastricht Treaty was signed) turned down the euro in a non-binding referendum in 2003,

and has circumvented the obligation to adopt the euro by not meeting

the monetary and budgetary requirements. All nations that have joined

the EU since 1993 have pledged to adopt the euro in due course. The

Maastricht Treaty was later amended by the Treaty of Nice, which closed the gaps and loopholes in the Maastricht and Rome Treaties.

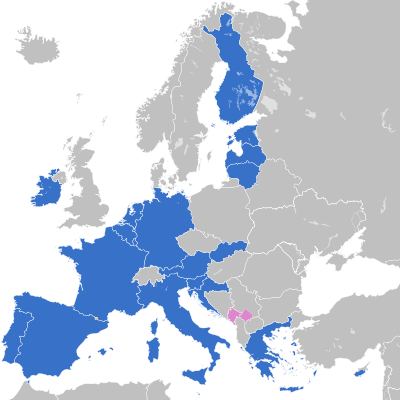

Eurozone members

The 20 participating members are

EU members not using the euro

The EU member states not in the Eurozone are Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Sweden.

Future eurozone members

The Bulgarian lev is targeted to be replaced by the euro on 1 January 2025.

The Romanian leu is targeted to be replaced by the euro sometime in 2029.

EU members Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Sweden

are legally obligated to adopt the euro eventually, though they have no

required date for adoption, and their governments do not currently have

any plans for switching. Denmark has negotiated for the right to not be required to switch.

Other users

Microstates with a monetary agreement:

EU special territories

Unilateral adopters

Pegged currencies

The currency of a number of states is pegged to the euro. These states are:

- Bosnia and Herzegovina (Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark, ISO 4217 code BAM)

- Bulgaria (Bulgarian lev, BGN)

- Cape Verde (Cape Verdean escudo, CVE)

- Cameroon (Central African CFA franc, XAF)

- Central African Republic (Central African CFA franc)

- Chad (Central African CFA franc)

- Equatorial Guinea (Central African CFA franc)

- Gabon (Central African CFA franc)

- Republic of the Congo (Central African CFA franc)

- French Polynesia (CFP franc, XFP)

- New Caledonia (CFP franc)

- Wallis and Futuna (CFP franc)

- Comoros (Comorian franc, KMF)

- Denmark (Danish krone, DKK)

- North Macedonia (Macedonian denar, MKD)

- Sovereign Military Order of Malta (Maltese scudo)

- São Tomé and Príncipe (São Tomé and Príncipe dobra, STN)

- Benin (West African CFA franc, XOF)

- Burkina Faso (West African CFA franc)

- Côte d'Ivoire (West African CFA franc)

- Guinea-Bissau (West African CFA franc)

- Mali (West African CFA franc)

- Niger (West African CFA franc)

- Senegal (West African CFA franc)

- Togo (West African CFA franc)

Coins and banknotes

Coins

The euro is divided into 100 cents (also referred to as euro cents,

especially when distinguishing them from other currencies, and referred

to as such on the common side of all cent coins). In Community

legislative acts the plural forms of euro and cent are spelled without the s, notwithstanding normal English usage. Otherwise, normal English plurals are used, with many local variations such as centime in France.

All circulating coins have a common side showing the denomination or value, and a map in the background. Due to the linguistic plurality in the European Union, the Latin alphabet version of euro is used (as opposed to the less common Greek or Cyrillic) and Arabic numerals

(other text is used on national sides in national languages, but other

text on the common side is avoided). For the denominations except the

1-, 2- and 5-cent coins, the map only showed the 15 member states which

were members when the euro was introduced. Beginning in 2007 or 2008

(depending on the country), the old map was replaced by a map of Europe

also showing countries outside the EU.

The 1-, 2- and 5-cent coins, however, keep their old design, showing a

geographical map of Europe with the 15 member states of 2002 raised

somewhat above the rest of the map. All common sides were designed by Luc Luycx. The coins also have a national side

showing an image specifically chosen by the country that issued the

coin. Euro coins from any member state may be freely used in any nation

that has adopted the euro.

The coins are issued in denominations of €2, €1, 50c, 20c, 10c, 5c, 2c, and 1c.

To avoid the use of the two smallest coins, some cash transactions are

rounded to the nearest five cents in the Netherlands and Ireland (by voluntary agreement) and in Finland and Italy (by law).

This practice is discouraged by the commission, as is the practice of

certain shops of refusing to accept high-value euro notes.

Commemorative coins

with €2 face value have been issued with changes to the design of the

national side of the coin. These include both commonly issued coins,

such as the €2 commemorative coin for the fiftieth anniversary of the

signing of the Treaty of Rome, and nationally issued coins, such as the

coin to commemorate the 2004 Summer Olympics

issued by Greece. These coins are legal tender throughout the eurozone.

Collector coins with various other denominations have been issued as

well, but these are not intended for general circulation, and they are

legal tender only in the member state that issued them.

Coin minting

A number of institutions are authorised to mint euro coins:

Banknotes

The design for the euro banknotes has common designs on both sides. The design was created by the Austrian designer Robert Kalina. Notes are issued in €500, €200, €100, €50, €20, €10, and €5.

Each banknote has its own colour and is dedicated to an artistic period

of European architecture. The front of the note features windows or

gateways while the back has bridges, symbolising links between states in

the union and with the future. While the designs are supposed to be

devoid of any identifiable characteristics, the initial designs by Robert Kalina were of specific bridges, including the Rialto and the Pont de Neuilly,

and were subsequently rendered more generic; the final designs still

bear very close similarities to their specific prototypes; thus they are

not truly generic. The monuments looked similar enough to different

national monuments to please everyone.

The Europa series, or second series, consists of six

denominations and no longer includes the €500 with issuance discontinued

as of 27 April 2019.

However, both the first and the second series of euro banknotes,

including the €500, remain legal tender throughout the euro area.

In December 2021, the ECB announced its plans to redesign euro

banknotes by 2024. A theme advisory group, made up of one member from

each euro area country, was selected to submit theme proposals to the

ECB. The proposals will be voted on by the public; a design competition

will also be held.

Issuing modalities for banknotes

Since 1 January 2002, the national central banks (NCBs) and the ECB have issued euro banknotes on a joint basis.

Eurosystem NCBs are required to accept euro banknotes put into

circulation by other Eurosystem members and these banknotes are not

repatriated. The ECB issues 8% of the total value of banknotes issued by

the Eurosystem.

In practice, the ECB's banknotes are put into circulation by the NCBs,

thereby incurring matching liabilities vis-à-vis the ECB. These

liabilities carry interest at the main refinancing rate of the ECB. The

other 92% of euro banknotes are issued by the NCBs in proportion to

their respective shares of the ECB capital key, calculated using national share of European Union (EU) population and national share of EU GDP, equally weighted.

Banknote printing

Member states are authorised to print or to commission bank note printing. As of November 2022, these are the printers:

Payments clearing, electronic funds transfer

Capital within the EU may be transferred in any amount from one state

to another. All intra-Union transfers in euro are treated as domestic

transactions and bear the corresponding domestic transfer costs. This includes all member states of the EU, even those outside the eurozone providing the transactions are carried out in euro.

Credit/debit card charging and ATM withdrawals within the eurozone are

also treated as domestic transactions; however paper-based payment

orders, like cheques, have not been standardised so these are still

domestic-based. The ECB has also set up a clearing system, TARGET, for large euro transactions.

History

Introduction

The euro was established by the provisions in the 1992 Maastricht Treaty. To participate in the currency, member states are meant to meet strict criteria, such as a budget deficit

of less than 3% of their GDP, a debt ratio of less than 60% of GDP

(both of which were ultimately widely flouted after introduction), low

inflation, and interest

rates close to the EU average. In the Maastricht Treaty, the United

Kingdom and Denmark were granted exemptions per their request from

moving to the stage of monetary union which resulted in the introduction

of the euro.

The name "euro" was officially adopted in Madrid on 16 December 1995. Belgian Esperantist Germain Pirlot, a former teacher of French and history, is credited with naming the new currency by sending a letter to then President of the European Commission, Jacques Santer, suggesting the name "euro" on 4 August 1995.

Due to differences in national conventions for rounding and significant digits, all conversion between the national currencies had to be carried out using the process of triangulation via the euro. The definitive values of one euro in terms of the exchange rates at which the currency entered the euro are shown on the right.

The rates were determined by the Council of the European Union,

based on a recommendation from the European Commission based on the

market rates on 31 December 1998. They were set so that one European Currency Unit

(ECU) would equal one euro. The European Currency Unit was an

accounting unit used by the EU, based on the currencies of the member

states; it was not a currency in its own right. They could not be set

earlier, because the ECU depended on the closing exchange rate of the

non-euro currencies (principally sterling) that day.

The procedure used to fix the conversion rate between the Greek drachma

and the euro was different since the euro by then was already two years

old. While the conversion rates for the initial eleven currencies were

determined only hours before the euro was introduced, the conversion

rate for the Greek drachma was fixed several months beforehand.

The currency was introduced in non-physical form (traveller's cheques,

electronic transfers, banking, etc.) at midnight on 1 January 1999,

when the national currencies of participating countries (the eurozone)

ceased to exist independently. Their exchange rates were locked at fixed

rates against each other. The euro thus became the successor to the European Currency Unit (ECU). The notes and coins for the old currencies, however, continued to be used as legal tender until new euro notes and coins were introduced on 1 January 2002.

The changeover period during which the former currencies' notes and

coins were exchanged for those of the euro lasted about two months,

until 28 February 2002. The official date on which the national

currencies ceased to be legal tender varied from member state to member

state. The earliest date was in Germany, where the mark

officially ceased to be legal tender on 31 December 2001, though the

exchange period lasted for two months more. Even after the old

currencies ceased to be legal tender, they continued to be accepted by

national central banks for periods ranging from several years to

indefinitely (the latter for Austria, Germany, Ireland, Estonia and

Latvia in banknotes and coins, and for Belgium, Luxembourg, Slovenia and

Slovakia in banknotes only). The earliest coins to become

non-convertible were the Portuguese escudos, which ceased to have monetary value after 31 December 2002, although banknotes remained exchangeable until 2022.

Currency sign

The euro sign; logotype and handwritten

A special euro currency sign (€) was designed after a public survey had narrowed the original ten proposals down to two. The European Commission then chose the design created by the Belgian artist Alain Billiet. Of the symbol, the Commission stated

Inspiration for the € symbol itself came from the Greek epsilon (Є) – a reference to the cradle of European civilisation – and the first letter of the word Europe, crossed by two parallel lines to 'certify' the stability of the euro.

The European Commission also specified a euro logo with exact proportions and foreground and background colour tones.

Placement of the currency sign relative to the numeric amount varies

from state to state, but for texts in English the symbol (or the ISO-standard "EUR") should precede the amount.

Eurozone crisis

Budget deficit of the eurozone compared to the United States and the United Kingdom.

Following the U.S. financial crisis in 2008, fears of a sovereign debt crisis developed in 2009 among investors concerning some European states, with the situation becoming particularly tense in early 2010. Greece was most acutely affected, but fellow Eurozone members Cyprus, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Spain were also significantly affected. All these countries used EU funds except Italy, which is a major donor to the EFSF. To be included in the eurozone, countries had to fulfil certain convergence criteria,

but the meaningfulness of such criteria was diminished by the fact it

was not enforced with the same level of strictness among countries.

According to the Economist Intelligence Unit

in 2011, "[I]f the [euro area] is treated as a single entity, its

[economic and fiscal] position looks no worse and in some respects,

rather better than that of the US or the UK" and the budget deficit for

the euro area as a whole is much lower and the euro area's government

debt/GDP ratio of 86% in 2010 was about the same level as that of the

United States. "Moreover", they write, "private-sector indebtedness

across the euro area as a whole is markedly lower than in the highly

leveraged Anglo-Saxon

economies". The authors conclude that the crisis "is as much political

as economic" and the result of the fact that the euro area lacks the

support of "institutional paraphernalia (and mutual bonds of solidarity) of a state".

The crisis continued with S&P downgrading the credit rating

of nine euro-area countries, including France, then downgrading the

entire European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) fund.

A historical parallel – to 1931 when Germany was burdened with

debt, unemployment and austerity while France and the United States were

relatively strong creditors – gained attention in summer 2012 even as Germany received a debt-rating warning of its own. In the enduring of this scenario the euro serves as a mean of quantitative primitive accumulation.

Direct and indirect usage

Agreed direct usage with minting rights

The euro is the sole currency of 20 EU member states:

Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany,

Greece, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the

Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Spain. These countries

constitute the "eurozone", some 347 million people in total as of 2023. According to bilateral agreements with the EU, the euro has also been designated as the sole and official currency in a further four European microstates

awarded minting rights (Andorra, Monaco, San Marino and the Vatican

City). With all but one (Denmark) EU members obliged to join when

economic conditions permit, together with future members of the EU, the enlargement of the eurozone is set to continue.

Agreed direct usage without minting rights

The euro is also the sole currency in three overseas territories of France that are not themselves part of the EU, namely Saint Barthélemy, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, and the French Southern and Antarctic Lands, as well as in the British Overseas Territory of Akrotiri and Dhekelia.

Unilateral direct usage

The

euro has been adopted unilaterally as the sole currency of Montenegro

and Kosovo. It has also been used as a foreign trading currency in Cuba

since 1998, Syria since 2006, and Venezuela since 2018. In 2009, Zimbabwe abandoned its local currency

and introduced major global convertible currencies instead, including

the euro and the United States dollar. The direct usage of the euro

outside of the official framework of the EU affects nearly 3 million

people.

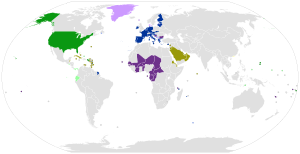

Currencies pegged to the euro

Worldwide use of the euro and the US dollar:

External adopters of the euro

Currencies pegged to the euro

Currencies pegged to the euro within narrow band

United States

External adopters of the US dollar

Currencies pegged to the US dollar

Currencies pegged to the US dollar within narrow band

Note: The Belarusian rouble is pegged to the euro, Russian rouble and US dollar in a currency basket.Outside the eurozone, two EU member states have currencies that are pegged to the euro, which is a precondition to joining the eurozone. The Danish krone and Bulgarian lev are pegged due to their participation in the ERM II.

Additionally, a total of 21 countries and territories that do not belong to the EU have currencies that are directly pegged to the euro including 14 countries in mainland Africa (CFA franc), two African island countries (Comorian franc and Cape Verdean escudo), three French Pacific territories (CFP franc) and two Balkan countries, Bosnia and Herzegovina (Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark) and North Macedonia (Macedonian denar). On 1 January 2010, the dobra of São Tomé and Príncipe was officially linked with the euro. Additionally, the Moroccan dirham is tied to a basket of currencies, including the euro and the US dollar, with the euro given the highest weighting.

These countries generally had previously implemented a currency peg to one of the major European currencies (e.g. the French franc, deutschmark or Portuguese escudo),

and when these currencies were replaced by the euro their currencies

became pegged to the euro. Pegging a country's currency to a major

currency is regarded as a safety measure, especially for currencies of

areas with weak economies, as the euro is seen as a stable currency,

prevents runaway inflation, and encourages foreign investment due to its

stability.

In total, as of 2013, 182 million people in Africa use a currency

pegged to the euro, 27 million people outside the eurozone in Europe,

and another 545,000 people on Pacific islands.

Since 2005, stamps issued by the Sovereign Military Order of Malta have been denominated in euro, although the Order's official currency remains the Maltese scudo. The Maltese scudo itself is pegged to the euro and is only recognised as legal tender within the Order.

Use as reserve currency

Since its introduction, the euro has been the second most widely held international reserve currency

after the U.S. dollar. The share of the euro as a reserve currency

increased from 18% in 1999 to 27% in 2008. Over this period, the share

held in U.S. dollar fell from 71% to 64% and that held in RMB fell from

6.4% to 3.3%. The euro inherited and built on the status of the deutschmark

as the second most important reserve currency. The euro remains

underweight as a reserve currency in advanced economies while overweight

in emerging and developing economies: according to the International Monetary Fund

the total of euro held as a reserve in the world at the end of 2008 was

equal to $1.1 trillion or €850 billion, with a share of 22% of all

currency reserves in advanced economies, but a total of 31% of all

currency reserves in emerging and developing economies.

The possibility of the euro becoming the first international reserve currency has been debated among economists. Former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan

gave his opinion in September 2007 that it was "absolutely conceivable

that the euro will replace the US dollar as reserve currency, or will be

traded as an equally important reserve currency".

In contrast to Greenspan's 2007 assessment, the euro's increase in the

share of the worldwide currency reserve basket has slowed considerably

since 2007 and since the beginning of the worldwide credit crunch related recession and European sovereign-debt crisis.

Economics

Optimal currency area

In economics, an optimum currency area, or region (OCA or OCR), is a

geographical region in which it would maximise economic efficiency to

have the entire region share a single currency. There are two models,

both proposed by Robert Mundell: the stationary expectations model and the international risk sharing model. Mundell himself advocates the international risk sharing model and thus concludes in favour of the euro. However, even before the creation of the single currency, there were concerns over diverging economies. Before the late-2000s recession it was considered unlikely that a state would leave the euro or the whole zone would collapse. However the Greek government-debt crisis led to former British Foreign Secretary Jack Straw claiming the eurozone could not last in its current form. Part of the problem seems to be the rules that were created when the euro was set up. John Lanchester, writing for The New Yorker, explains it:

The

guiding principle of the currency, which opened for business in 1999,

were supposed to be a set of rules to limit a country's annual deficit

to three per cent of gross domestic product, and the total accumulated

debt to sixty per cent of G.D.P. It was a nice idea, but by 2004 the two

biggest economies in the euro zone, Germany and France, had broken the

rules for three years in a row.

Transaction costs and risks

The most obvious benefit of adopting a single currency is to remove

the cost of exchanging currency, theoretically allowing businesses and

individuals to consummate previously unprofitable trades. For consumers,

banks in the eurozone must charge the same for intra-member

cross-border transactions as purely domestic transactions for electronic

payments (e.g., credit cards, debit cards and cash machine withdrawals).

Financial markets on the continent are expected to be far more liquid

and flexible than they were in the past. The reduction in cross-border

transaction costs will allow larger banking firms to provide a wider

array of banking services that can compete across and beyond the

eurozone. However, although transaction costs were reduced, some studies

have shown that risk aversion has increased during the last 40 years in the Eurozone.

Price parity

Another

effect of the common European currency is that differences in prices—in

particular in price levels—should decrease because of the law of one price. Differences in prices can trigger arbitrage, i.e., speculative trade in a commodity

across borders purely to exploit the price differential. Therefore,

prices on commonly traded goods are likely to converge, causing

inflation in some regions and deflation in others during the transition.

Some evidence of this has been observed in specific eurozone markets.

Macroeconomic stability

Before

the introduction of the euro, some countries had successfully contained

inflation, which was then seen as a major economic problem, by

establishing largely independent central banks. One such bank was the Bundesbank in Germany; the European Central Bank was modelled on the Bundesbank.

The euro has come under criticism due to its regulation, lack of

flexibility and rigidity towards sharing member states on issues such as

nominal interest rates.

Many national and corporate bonds

denominated in euro are significantly more liquid and have lower

interest rates than was historically the case when denominated in

national currencies. While increased liquidity may lower the nominal interest rate

on the bond, denominating the bond in a currency with low levels of

inflation arguably plays a much larger role. A credible commitment to

low levels of inflation and a stable debt reduces the risk that the

value of the debt will be eroded by higher levels of inflation or

default in the future, allowing debt to be issued at a lower nominal

interest rate.

Unfortunately, there is also a cost in structurally keeping

inflation lower than in the United States, UK, and China. The result is

that seen from those countries, the euro has become expensive, making

European products increasingly expensive for its largest importers;

hence export from the eurozone becomes more difficult.

In general, those in Europe who own large amounts of euro are served by high stability and low inflation.

A monetary union means states in that union lose the main mechanism of recovery of their international competitiveness by weakening (depreciating) their currency. When wages become too high compared to productivity

in the exports sector, then these exports become more expensive and

they are crowded out from the market within a country and abroad. This

drives the fall of employment and output in the exports sector and fall

of trade and current account

balances. Fall of output and employment in the tradable goods sector

may be offset by the growth of non-exports sectors, especially in construction and services. Increased purchases abroad and negative current account balances can be financed without a problem as long as credit is cheap.

The need to finance trade deficit weakens currency, making exports

automatically more attractive in a country and abroad. A state in a

monetary union cannot use weakening of currency to recover its

international competitiveness. To achieve this a state has to reduce

prices, including wages (deflation). This could result in high unemployment and lower incomes as it was during the European sovereign-debt crisis.

Trade

The euro increased price transparency and stimulated cross-border trade.

A 2009 consensus from the studies of the introduction of the euro

concluded that it has increased trade within the eurozone by 5% to 10%, although one study suggested an increase of only 3% while another estimated 9 to 14%. However, a meta-analysis of all available studies suggests that the prevalence of positive estimates is caused by publication bias and that the underlying effect may be negligible.

Although a more recent meta-analysis shows that publication bias

decreases over time and that there are positive trade effects from the

introduction of the euro, as long as results from before 2010 are taken

into account. This may be because of the inclusion of the Financial crisis of 2007–2008 and ongoing integration within the EU. Furthermore, older studies accounting for time trend

reflecting general cohesion policies in Europe that started before, and

continue after implementing the common currency find no effect on

trade. These results suggest that other policies aimed at European integration

might be the source of observed increase in trade. According to Barry

Eichengreen, studies disagree on the magnitude of the effect of the euro

on trade, but they agree that it did have an effect.

Investment

Physical investment seems to have increased by 5% in the eurozone due to the introduction.

Regarding foreign direct investment, a study found that the

intra-eurozone FDI stocks have increased by about 20% during the first

four years of the EMU.

Concerning the effect on corporate investment, there is evidence that

the introduction of the euro has resulted in an increase in investment

rates and that it has made it easier for firms to access financing in

Europe. The euro has most specifically stimulated investment in

companies that come from countries that previously had weak currencies. A

study found that the introduction of the euro accounts for 22% of the

investment rate after 1998 in countries that previously had a weak

currency.

Inflation

The introduction of the euro has led to extensive discussion about

its possible effect on inflation. In the short term, there was a

widespread impression in the population of the eurozone that the

introduction of the euro had led to an increase in prices, but this

impression was not confirmed by general indices of inflation and other

studies.

A study of this paradox found that this was due to an asymmetric effect

of the introduction of the euro on prices: while it had no effect on

most goods, it had an effect on cheap goods which have seen their price

round up after the introduction of the euro. The study found that

consumers based their beliefs on inflation of those cheap goods which

are frequently purchased.

It has also been suggested that the jump in small prices may be because

prior to the introduction, retailers made fewer upward adjustments and

waited for the introduction of the euro to do so.

Exchange rate risk

One

of the advantages of the adoption of a common currency is the reduction

of the risk associated with changes in currency exchange rates.

It has been found that the introduction of the euro created

"significant reductions in market risk exposures for nonfinancial firms

both in and outside Europe".

These reductions in market risk "were concentrated in firms domiciled

in the eurozone and in non-euro firms with a high fraction of foreign

sales or assets in Europe".

Financial integration

The introduction of the euro increased European financial integration, which helped stimulate growth of a European securities market (bond markets are characterized by economies of scale dynamics).

According to a study on this question, it has "significantly reshaped

the European financial system, especially with respect to the securities

markets [...] However, the real and policy barriers to integration in

the retail and corporate banking sectors remain significant, even if the

wholesale end of banking has been largely integrated." Specifically, the euro has significantly decreased the cost of trade in bonds, equity, and banking assets within the eurozone.

On a global level, there is evidence that the introduction of the euro

has led to an integration in terms of investment in bond portfolios,

with eurozone countries lending and borrowing more between each other

than with other countries. Financial integration made it cheaper for European companies to borrow.

Banks, firms and households could also invest more easily outside of

their own country, thus creating greater international risk-sharing.

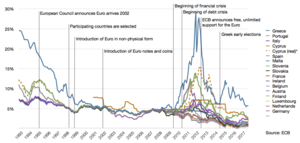

Effect on interest rates

Secondary market yields of government bonds with maturities of close to 10 years

As of January 2014, and since the introduction of the euro, interest

rates of most member countries (particularly those with a weak currency)

have decreased. Some of these countries had the most serious sovereign

financing problems.

The effect of declining interest rates, combined with excess

liquidity continually provided by the ECB, made it easier for banks

within the countries in which interest rates fell the most, and their

linked sovereigns, to borrow significant amounts (above the 3% of GDP

budget deficit imposed on the eurozone initially) and significantly

inflate their public and private debt levels. Following the financial crisis of 2007–2008,

governments in these countries found it necessary to bail out or

nationalise their privately held banks to prevent systemic failure of

the banking system when underlying hard or financial asset values were

found to be grossly inflated and sometimes so nearly worthless there was

no liquid market for them.

This further increased the already high levels of public debt to a

level the markets began to consider unsustainable, via increasing

government bond interest rates, producing the ongoing European

sovereign-debt crisis.

Price convergence

The

evidence on the convergence of prices in the eurozone with the

introduction of the euro is mixed. Several studies failed to find any

evidence of convergence following the introduction of the euro after a

phase of convergence in the early 1990s. Other studies have found evidence of price convergence, in particular for cars.

A possible reason for the divergence between the different studies is

that the processes of convergence may not have been linear, slowing down

substantially between 2000 and 2003, and resurfacing after 2003 as

suggested by a recent study (2009).

Tourism

A study

suggests that the introduction of the euro has had a positive effect on

the amount of tourist travel within the EMU, with an increase of 6.5%.

Exchange rates

Flexible exchange rates

The ECB targets interest rates rather than exchange rates and in general, does not intervene on the foreign exchange rate markets. This is because of the implications of the Mundell–Fleming model, which implies a central bank cannot (without capital controls) maintain interest rate and exchange rate targets simultaneously, because increasing the money supply results in a depreciation of the currency. In the years following the Single European Act, the EU has liberalised its capital markets and, as the ECB has inflation targeting as its monetary policy, the exchange-rate regime of the euro is floating.

Against other major currencies

The euro is the second-most widely held reserve currency

after the U.S. dollar. After its introduction on 4 January 1999 its

exchange rate against the other major currencies fell reaching its

lowest exchange rates in 2000 (3 May vs sterling, 25 October vs the U.S. dollar, 26 October vs Japanese yen).

Afterwards it regained and its exchange rate reached its historical

highest point in 2008 (15 July vs US dollar, 23 July vs Japanese yen, 29

December vs sterling). With the advent of the global financial crisis

the euro initially fell, to regain later. Despite pressure due to the European sovereign-debt crisis the euro remained stable.

In November 2011 the euro's exchange rate index – measured against

currencies of the bloc's major trading partners – was trading almost two

percent higher on the year, approximately at the same level as it was

before the crisis kicked off in 2007. In mid July, 2022, the euro equalled the US dollar for a short period of time.

Euro exchange rate against US dollar (USD), sterling (GBP) and Japanese yen (JPY), starting from 1999.

- Current and historical exchange rates against 32 other currencies (European Central Bank): link

Political considerations

Besides

the economic motivations to the introduction of the euro, its creation

was also partly justified as a way to foster a closer sense of joint

identity between European citizens. Statements about this goal were for

instance made by Wim Duisenberg, European Central Bank Governor, in 1998, Laurent Fabius, French Finance Minister, in 2000, and Romano Prodi, President of the European Commission, in 2002.

However, 15 years after the introduction of the euro, a study found no

evidence that it has had a positive influence on a shared sense of

European identity (and no evidence that it had a negative effect

either).

Euro in various languages

The formal titles of the currency are euro for the major unit and cent

for the minor (one-hundredth) unit and for official use in most

eurozone languages; according to the ECB, all languages should use the

same spelling for the nominative singular. This may contradict normal rules for word formation in some languages, e.g., those in which there is no eu diphthong.

Bulgaria has negotiated an exception; euro in the Bulgarian Cyrillic alphabet is spelled eвро (evro) and not eуро (euro) in all official documents.

In the Greek script the term ευρώ (evró) is used; the Greek "cent"

coins are denominated in λεπτό/ά (leptó/á). Official practice for

English-language EU legislation is to use the words euro and cent as

both singular and plural, although the European Commission's Directorate-General for Translation states that the plural forms euros and cents should be used in English.

The word 'euro' is pronounced differently according to pronunciation rules in the individual languages applied; in German [ˈɔɪ̯ʁo], in English [ˈjuəɹəu], in French [øˈʁo], etc.