The cell cycle, or cell-division cycle, is the series of events that take place in a cell that cause it to divide into two daughter cells. These events include the duplication of its DNA (DNA replication) and some of its organelles, and subsequently the partitioning of its cytoplasm and other components into two daughter cells in a process called cell division.

In cells with nuclei (eukaryotes), (i.e., animal, plant, fungal, and protist cells), the cell cycle is divided into two main stages: interphase and the mitotic (M) phase (including mitosis and cytokinesis). During interphase, the cell grows, accumulating nutrients needed for mitosis, and replicates its DNA and some of its organelles. During the mitotic phase, the replicated chromosomes, organelles, and cytoplasm separate into two new daughter cells. To ensure the proper replication of cellular components and division, there are control mechanisms known as cell cycle checkpoints after each of the key steps of the cycle that determine if the cell can progress to the next phase.

In cells without nuclei (prokaryotes), (i.e., bacteria and archaea), the cell cycle is divided into the B, C, and D periods. The B period extends from the end of cell division to the beginning of DNA replication. DNA replication occurs during the C period. The D period refers to the stage between the end of DNA replication and the splitting of the bacterial cell into two daughter cells.

The cell-division cycle is a vital process by which a single-celled fertilized egg develops into a mature organism, as well as the process by which hair, skin, blood cells, and some internal organs are renewed. After cell division, each of the daughter cells begin the interphase of a new cycle. Although the various stages of interphase are not usually morphologically distinguishable, each phase of the cell cycle has a distinct set of specialized biochemical processes that prepare the cell for initiation of the cell division.

Phases

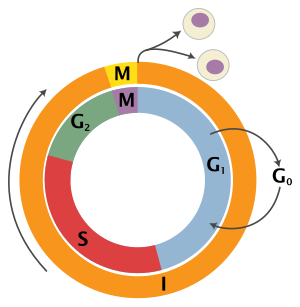

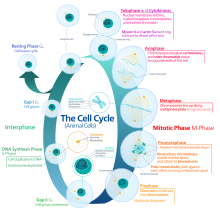

The eukaryotic cell cycle consists of four distinct phases: G1 phase, S phase (synthesis), G2 phase (collectively known as interphase) and M phase (mitosis and cytokinesis). M phase is itself composed of two tightly coupled processes: mitosis, in which the cell's nucleus divides, and cytokinesis, in which the cell's cytoplasm divides forming two daughter cells. Activation of each phase is dependent on the proper progression and completion of the previous one. Cells that have temporarily or reversibly stopped dividing are said to have entered a state of quiescence called G0 phase.

| State | Phase | Abbreviation | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resting | Gap 0 | G0 | A phase where the cell has left the cycle and has stopped dividing. |

| Interphase | Gap 1 | G1 | Cells increase in size in Gap 1. The G1 checkpoint control mechanism ensures that everything is ready for DNA synthesis. |

| Synthesis | S | DNA replication occurs during this phase. | |

| Gap 2 | G2 | During the gap between DNA synthesis and mitosis, the cell will continue to grow. The G2 checkpoint control mechanism ensures that everything is ready to enter the M (mitosis) phase and divide. | |

| Cell division | Mitosis | M | Cell growth stops at this stage and cellular energy is focused on the orderly division into two daughter cells. A checkpoint in the middle of mitosis (Metaphase Checkpoint) ensures that the cell is ready to complete cell division. |

After cell division, each of the daughter cells begin the interphase of a new cycle. Although the various stages of interphase are not usually morphologically distinguishable, each phase of the cell cycle has a distinct set of specialized biochemical processes that prepare the cell for initiation of cell division.

G0 phase (quiescence)

G0 is a resting phase where the cell has left the cycle and has stopped dividing. The cell cycle starts with this phase. Non-proliferative (non-dividing) cells in multicellular eukaryotes generally enter the quiescent G0 state from G1 and may remain quiescent for long periods of time, possibly indefinitely (as is often the case for neurons). This is very common for cells that are fully differentiated. Some cells enter the G0 phase semi-permanently and are considered post-mitotic, e.g., some liver, kidney, and stomach cells. Many cells do not enter G0 and continue to divide throughout an organism's life, e.g., epithelial cells.

The word "post-mitotic" is sometimes used to refer to both quiescent and senescent cells. Cellular senescence occurs in response to DNA damage and external stress and usually constitutes an arrest in G1. Cellular senescence may make a cell's progeny nonviable; it is often a biochemical alternative to the self-destruction of such a damaged cell by apoptosis.

Interphase

Interphase represent the phase between two successive M phases. Interphase is a series of changes that takes place in a newly formed cell and its nucleus before it becomes capable of division again. It is also called preparatory phase or intermitosis. Typically interphase lasts for at least 91% of the total time required for the cell cycle.

Interphase proceeds in three stages, G1, S, and G2, followed by the cycle of mitosis and cytokinesis. The cell's nuclear DNA contents are duplicated during S phase.

G1 phase (First growth phase or Post mitotic gap phase)

The first phase within interphase, from the end of the previous M phase until the beginning of DNA synthesis, is called G1 (G indicating gap). It is also called the growth phase. During this phase, the biosynthetic activities of the cell, which are considerably slowed down during M phase, resume at a high rate. The duration of G1 is highly variable, even among different cells of the same species. In this phase, the cell increases its supply of proteins, increases the number of organelles (such as mitochondria, ribosomes), and grows in size. In G1 phase, a cell has three options.

- To continue cell cycle and enter S phase

- Stop cell cycle and enter G0 phase for undergoing differentiation.

- Become arrested in G1 phase hence it may enter G0 phase or re-enter cell cycle.

The deciding point is called check point (Restriction point). This check point is called the restriction point or START and is regulated by G1/S cyclins, which cause transition from G1 to S phase. Passage through the G1 check point commits the cell to division.

S phase (DNA replication)

The ensuing S phase starts when DNA synthesis commences; when it is complete, all of the chromosomes have been replicated, i.e., each chromosome consists of two sister chromatids. Thus, during this phase, the amount of DNA in the cell has doubled, though the ploidy and number of chromosomes are unchanged. Rates of RNA transcription and protein synthesis are very low during this phase. An exception to this is histone production, most of which occurs during the S phase.

G2 phase (growth)

G2 phase occurs after DNA replication and is a period of protein synthesis and rapid cell growth to prepare the cell for mitosis. During this phase microtubules begin to reorganize to form a spindle (preprophase). Before proceeding to mitotic phase, cells must be checked at the G2 checkpoint for any DNA damage within the chromosomes. The G2 checkpoint is mainly regulated by the tumor protein p53. If the DNA is damaged, p53 will either repair the DNA or trigger the apoptosis of the cell. If p53 is dysfunctional or mutated, cells with damaged DNA may continue through the cell cycle, leading to the development of cancer.

Mitotic phase (chromosome separation)

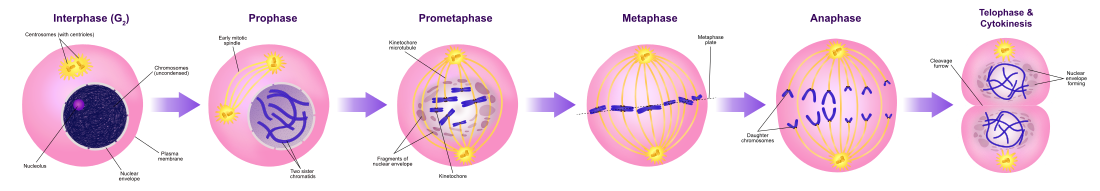

The relatively brief M phase consists of nuclear division (karyokinesis). It is a relatively short period of the cell cycle. M phase is complex and highly regulated. The sequence of events is divided into phases, corresponding to the completion of one set of activities and the start of the next. These phases are sequentially known as:

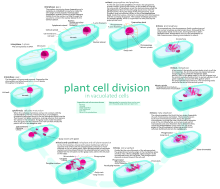

Mitosis is the process by which a eukaryotic cell separates the chromosomes in its cell nucleus into two identical sets in two nuclei. During the process of mitosis the pairs of chromosomes condense and attach to microtubules that pull the sister chromatids to opposite sides of the cell.

Mitosis occurs exclusively in eukaryotic cells, but occurs in different ways in different species. For example, animal cells undergo an "open" mitosis, where the nuclear envelope breaks down before the chromosomes separate, while fungi such as Aspergillus nidulans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (yeast) undergo a "closed" mitosis, where chromosomes divide within an intact cell nucleus.

Cytokinesis phase (separation of all cell components)

Mitosis is immediately followed by cytokinesis, which divides the nuclei, cytoplasm, organelles and cell membrane into two cells containing roughly equal shares of these cellular components. Mitosis and cytokinesis together define the division of the mother cell into two daughter cells, genetically identical to each other and to their parent cell. This accounts for approximately 10% of the cell cycle.

Because cytokinesis usually occurs in conjunction with mitosis, "mitosis" is often used interchangeably with "M phase". However, there are many cells where mitosis and cytokinesis occur separately, forming single cells with multiple nuclei in a process called endoreplication. This occurs most notably among the fungi and slime molds, but is found in various groups. Even in animals, cytokinesis and mitosis may occur independently, for instance during certain stages of fruit fly embryonic development. Errors in mitosis can result in cell death through apoptosis or cause mutations that may lead to cancer.

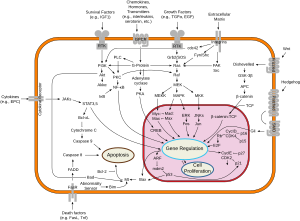

Regulation of eukaryotic cell cycle

Regulation of the cell cycle involves processes crucial to the survival of a cell, including the detection and repair of genetic damage as well as the prevention of uncontrolled cell division. The molecular events that control the cell cycle are ordered and directional; that is, each process occurs in a sequential fashion and it is impossible to "reverse" the cycle.

Role of cyclins and CDKs

Nobel Laureate Paul Nurse |

Nobel Laureate Tim Hunt |

Two key classes of regulatory molecules, cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), determine a cell's progress through the cell cycle. Leland H. Hartwell, R. Timothy Hunt, and Paul M. Nurse won the 2001 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their discovery of these central molecules. Many of the genes encoding cyclins and CDKs are conserved among all eukaryotes, but in general, more complex organisms have more elaborate cell cycle control systems that incorporate more individual components. Many of the relevant genes were first identified by studying yeast, especially Saccharomyces cerevisiae; genetic nomenclature in yeast dubs many of these genes cdc (for "cell division cycle") followed by an identifying number, e.g. cdc25 or cdc20.

Cyclins form the regulatory subunits and CDKs the catalytic subunits of an activated heterodimer; cyclins have no catalytic activity and CDKs are inactive in the absence of a partner cyclin. When activated by a bound cyclin, CDKs perform a common biochemical reaction called phosphorylation that activates or inactivates target proteins to orchestrate coordinated entry into the next phase of the cell cycle. Different cyclin-CDK combinations determine the downstream proteins targeted. CDKs are constitutively expressed in cells whereas cyclins are synthesised at specific stages of the cell cycle, in response to various molecular signals.

General mechanism of cyclin-CDK interaction

Upon receiving a pro-mitotic extracellular signal, G1 cyclin-CDK complexes become active to prepare the cell for S phase, promoting the expression of transcription factors that in turn promote the expression of S cyclins and of enzymes required for DNA replication. The G1 cyclin-CDK complexes also promote the degradation of molecules that function as S phase inhibitors by targeting them for ubiquitination. Once a protein has been ubiquitinated, it is targeted for proteolytic degradation by the proteasome. However, results from a recent study of E2F transcriptional dynamics at the single-cell level argue that the role of G1 cyclin-CDK activities, in particular cyclin D-CDK4/6, is to tune the timing rather than the commitment of cell cycle entry.

Active S cyclin-CDK complexes phosphorylate proteins that make up the pre-replication complexes assembled during G1 phase on DNA replication origins. The phosphorylation serves two purposes: to activate each already-assembled pre-replication complex, and to prevent new complexes from forming. This ensures that every portion of the cell's genome will be replicated once and only once. The reason for prevention of gaps in replication is fairly clear, because daughter cells that are missing all or part of crucial genes will die. However, for reasons related to gene copy number effects, possession of extra copies of certain genes is also deleterious to the daughter cells.

Mitotic cyclin-CDK complexes, which are synthesized but inactivated during S and G2 phases, promote the initiation of mitosis by stimulating downstream proteins involved in chromosome condensation and mitotic spindle assembly. A critical complex activated during this process is a ubiquitin ligase known as the anaphase-promoting complex (APC), which promotes degradation of structural proteins associated with the chromosomal kinetochore. APC also targets the mitotic cyclins for degradation, ensuring that telophase and cytokinesis can proceed.

Specific action of cyclin-CDK complexes

Cyclin D is the first cyclin produced in the cells that enter the cell cycle, in response to extracellular signals (e.g. growth factors). Cyclin D levels stay low in resting cells that are not proliferating. Additionally, CDK4/6 and CDK2 are also inactive because CDK4/6 are bound by INK4 family members (e.g., p16), limiting kinase activity. Meanwhile, CDK2 complexes are inhibited by the CIP/KIP proteins such as p21 and p27, When it is time for a cell to enter the cell cycle, which is triggered by a mitogenic stimuli, levels of cyclin D increase. In response to this trigger, cyclin D binds to existing CDK4/6, forming the active cyclin D-CDK4/6 complex. Cyclin D-CDK4/6 complexes in turn mono-phosphorylates the retinoblastoma susceptibility protein (Rb) to pRb. The un-phosphorylated Rb tumour suppressor functions in inducing cell cycle exit and maintaining G0 arrest (senescence).

In the last few decades, a model has been widely accepted whereby pRB proteins are inactivated by cyclin D-Cdk4/6-mediated phosphorylation. Rb has 14+ potential phosphorylation sites. Cyclin D-Cdk 4/6 progressively phosphorylates Rb to hyperphosphorylated state, which triggers dissociation of pRB–E2F complexes, thereby inducing G1/S cell cycle gene expression and progression into S phase.

However, scientific observations from a recent study show that Rb is present in three types of isoforms: (1) un-phosphorylated Rb in G0 state; (2) mono-phosphorylated Rb, also referred to as "hypo-phosphorylated' or 'partially' phosphorylated Rb in early G1 state; and (3) inactive hyper-phosphorylated Rb in late G1 state. In early G1 cells, mono-phosphorylated Rb exits as 14 different isoforms, one of each has distinct E2F binding affinity. Rb has been found to associate with hundreds of different proteins and the idea that different mono-phosphorylated Rb isoforms have different protein partners was very appealing. A recent report confirmed that mono-phosphorylation controls Rb's association with other proteins and generates functional distinct forms of Rb. All different mono-phosphorylated Rb isoforms inhibit E2F transcriptional program and are able to arrest cells in G1-phase. Importantly, different mono-phosphorylated forms of RB have distinct transcriptional outputs that are extended beyond E2F regulation.

In general, the binding of pRb to E2F inhibits the E2F target gene expression of certain G1/S and S transition genes including E-type cyclins. The partial phosphorylation of RB de-represses the Rb-mediated suppression of E2F target gene expression, begins the expression of cyclin E. The molecular mechanism that causes the cell switched to cyclin E activation is currently not known, but as cyclin E levels rise, the active cyclin E-CDK2 complex is formed, bringing Rb to be inactivated by hyper-phosphorylation. Hyperphosphorylated Rb is completely dissociated from E2F, enabling further expression of a wide range of E2F target genes are required for driving cells to proceed into S phase. Recently, it has been identified that cyclin D-Cdk4/6 binds to a C-terminal alpha-helix region of Rb that is only distinguishable to cyclin D rather than other cyclins, cyclin E, A and B. This observation based on the structural analysis of Rb phosphorylation supports that Rb is phosphorylated in a different level through multiple Cyclin-Cdk complexes. This also makes feasible the current model of a simultaneous switch-like inactivation of all mono-phosphorylated Rb isoforms through one type of Rb hyper-phosphorylation mechanism. In addition, mutational analysis of the cyclin D- Cdk 4/6 specific Rb C-terminal helix shows that disruptions of cyclin D-Cdk 4/6 binding to Rb prevents Rb phosphorylation, arrests cells in G1, and bolsters Rb's functions in tumor suppressor. This cyclin-Cdk driven cell cycle transitional mechanism governs a cell committed to the cell cycle that allows cell proliferation. A cancerous cell growth often accompanies with deregulation of Cyclin D-Cdk 4/6 activity.

The hyperphosphorylated Rb dissociates from the E2F/DP1/Rb complex (which was bound to the E2F responsive genes, effectively "blocking" them from transcription), activating E2F. Activation of E2F results in transcription of various genes like cyclin E, cyclin A, DNA polymerase, thymidine kinase, etc. Cyclin E thus produced binds to CDK2, forming the cyclin E-CDK2 complex, which pushes the cell from G1 to S phase (G1/S, which initiates the G2/M transition). Cyclin B-cdk1 complex activation causes breakdown of nuclear envelope and initiation of prophase, and subsequently, its deactivation causes the cell to exit mitosis. A quantitative study of E2F transcriptional dynamics at the single-cell level by using engineered fluorescent reporter cells provided a quantitative framework for understanding the control logic of cell cycle entry, challenging the canonical textbook model. Genes that regulate the amplitude of E2F accumulation, such as Myc, determine the commitment in cell cycle and S phase entry. G1 cyclin-CDK activities are not the driver of cell cycle entry. Instead, they primarily tune the timing of E2F increase, thereby modulating the pace of cell cycle progression.

Inhibitors

Endogenous

Two families of genes, the cip/kip (CDK interacting protein/Kinase inhibitory protein) family and the INK4a/ARF (Inhibitor of Kinase 4/Alternative Reading Frame) family, prevent the progression of the cell cycle. Because these genes are instrumental in prevention of tumor formation, they are known as tumor suppressors.

The cip/kip family includes the genes p21, p27 and p57. They halt the cell cycle in G1 phase by binding to and inactivating cyclin-CDK complexes. p21 is activated by p53 (which, in turn, is triggered by DNA damage e.g. due to radiation). p27 is activated by Transforming Growth Factor β (TGF β), a growth inhibitor.

The INK4a/ARF family includes p16INK4a, which binds to CDK4 and arrests the cell cycle in G1 phase, and p14ARF which prevents p53 degradation.

Synthetic

Synthetic inhibitors of Cdc25 could also be useful for the arrest of cell cycle and therefore be useful as antineoplastic and anticancer agents.

Many human cancers possess the hyper-activated Cdk 4/6 activities. Given the observations of cyclin D-Cdk 4/6 functions, inhibition of Cdk 4/6 should result in preventing a malignant tumor from proliferating. Consequently, scientists have tried to invent the synthetic Cdk4/6 inhibitor as Cdk4/6 has been characterized to be a therapeutic target for anti-tumor effectiveness. Three Cdk4/6 inhibitors - palbociclib, ribociclib, and abemaciclib - currently received FDA approval for clinical use to treat advanced-stage or metastatic, hormone-receptor-positive (HR-positive, HR+), HER2-negative (HER2-) breast cancer. For example, palbociclib is an orally active CDK4/6 inhibitor which has demonstrated improved outcomes for ER-positive/HER2-negative advanced breast cancer. The main side effect is neutropenia which can be managed by dose reduction.

Cdk4/6 targeted therapy will only treat cancer types where Rb is expressed. Cancer cells with loss of Rb have primary resistance to Cdk4/6 inhibitors.

Transcriptional regulatory network

Current evidence suggests that a semi-autonomous transcriptional network acts in concert with the CDK-cyclin machinery to regulate the cell cycle. Several gene expression studies in Saccharomyces cerevisiae have identified 800–1200 genes that change expression over the course of the cell cycle. They are transcribed at high levels at specific points in the cell cycle, and remain at lower levels throughout the rest of the cycle. While the set of identified genes differs between studies due to the computational methods and criteria used to identify them, each study indicates that a large portion of yeast genes are temporally regulated.

Many periodically expressed genes are driven by transcription factors that are also periodically expressed. One screen of single-gene knockouts identified 48 transcription factors (about 20% of all non-essential transcription factors) that show cell cycle progression defects. Genome-wide studies using high throughput technologies have identified the transcription factors that bind to the promoters of yeast genes, and correlating these findings with temporal expression patterns have allowed the identification of transcription factors that drive phase-specific gene expression. The expression profiles of these transcription factors are driven by the transcription factors that peak in the prior phase, and computational models have shown that a CDK-autonomous network of these transcription factors is sufficient to produce steady-state oscillations in gene expression).

Experimental evidence also suggests that gene expression can oscillate with the period seen in dividing wild-type cells independently of the CDK machinery. Orlando et al. used microarrays to measure the expression of a set of 1,271 genes that they identified as periodic in both wild type cells and cells lacking all S-phase and mitotic cyclins (clb1,2,3,4,5,6). Of the 1,271 genes assayed, 882 continued to be expressed in the cyclin-deficient cells at the same time as in the wild type cells, despite the fact that the cyclin-deficient cells arrest at the border between G1 and S phase. However, 833 of the genes assayed changed behavior between the wild type and mutant cells, indicating that these genes are likely directly or indirectly regulated by the CDK-cyclin machinery. Some genes that continued to be expressed on time in the mutant cells were also expressed at different levels in the mutant and wild type cells. These findings suggest that while the transcriptional network may oscillate independently of the CDK-cyclin oscillator, they are coupled in a manner that requires both to ensure the proper timing of cell cycle events. Other work indicates that phosphorylation, a post-translational modification, of cell cycle transcription factors by Cdk1 may alter the localization or activity of the transcription factors in order to tightly control timing of target genes.

While oscillatory transcription plays a key role in the progression of the yeast cell cycle, the CDK-cyclin machinery operates independently in the early embryonic cell cycle. Before the midblastula transition, zygotic transcription does not occur and all needed proteins, such as the B-type cyclins, are translated from maternally loaded mRNA.

DNA replication and DNA replication origin activity

Analyses of synchronized cultures of Saccharomyces cerevisiae under conditions that prevent DNA replication initiation without delaying cell cycle progression showed that origin licensing decreases the expression of genes with origins near their 3' ends, revealing that downstream origins can regulate the expression of upstream genes. This confirms previous predictions from mathematical modeling of a global causal coordination between DNA replication origin activity and mRNA expression, and shows that mathematical modeling of DNA microarray data can be used to correctly predict previously unknown biological modes of regulation.

Checkpoints

Cell cycle checkpoints are used by the cell to monitor and regulate the progress of the cell cycle. Checkpoints prevent cell cycle progression at specific points, allowing verification of necessary phase processes and repair of DNA damage. The cell cannot proceed to the next phase until checkpoint requirements have been met. Checkpoints typically consist of a network of regulatory proteins that monitor and dictate the progression of the cell through the different stages of the cell cycle.

It is estimated that in normal human cells about 1% of single-strand DNA damages are converted to about 50 endogenous DNA double-strand breaks per cell per cell cycle. Although such double-strand breaks are usually repaired with high fidelity, errors in their repair are considered to contribute significantly to the rate of cancer in humans.

There are several checkpoints to ensure that damaged or incomplete DNA is not passed on to daughter cells. Three main checkpoints exist: the G1/S checkpoint, the G2/M checkpoint and the metaphase (mitotic) checkpoint. Another checkpoint is the Go checkpoint, in which the cells are checked for maturity. If the cells fail to pass this checkpoint by not being ready yet, they will be discarded from dividing.

G1/S transition is a rate-limiting step in the cell cycle and is also known as restriction point. This is where the cell checks whether it has enough raw materials to fully replicate its DNA (nucleotide bases, DNA synthase, chromatin, etc.). An unhealthy or malnourished cell will get stuck at this checkpoint.

The G2/M checkpoint is where the cell ensures that it has enough cytoplasm and phospholipids for two daughter cells. But sometimes more importantly, it checks to see if it is the right time to replicate. There are some situations where many cells need to all replicate simultaneously (for example, a growing embryo should have a symmetric cell distribution until it reaches the mid-blastula transition). This is done by controlling the G2/M checkpoint.

The metaphase checkpoint is a fairly minor checkpoint, in that once a cell is in metaphase, it has committed to undergoing mitosis. However that's not to say it isn't important. In this checkpoint, the cell checks to ensure that the spindle has formed and that all of the chromosomes are aligned at the spindle equator before anaphase begins.

While these are the three "main" checkpoints, not all cells have to pass through each of these checkpoints in this order to replicate. Many types of cancer are caused by mutations that allow the cells to speed through the various checkpoints or even skip them altogether. Going from S to M to S phase almost consecutively. Because these cells have lost their checkpoints, any DNA mutations that may have occurred are disregarded and passed on to the daughter cells. This is one reason why cancer cells have a tendency to exponentially accrue mutations. Aside from cancer cells, many fully differentiated cell types no longer replicate so they leave the cell cycle and stay in G0 until their death. Thus removing the need for cellular checkpoints. An alternative model of the cell cycle response to DNA damage has also been proposed, known as the postreplication checkpoint.

Checkpoint regulation plays an important role in an organism's development. In sexual reproduction, when egg fertilization occurs, when the sperm binds to the egg, it releases signalling factors that notify the egg that it has been fertilized. Among other things, this induces the now fertilized oocyte to return from its previously dormant, G0, state back into the cell cycle and on to mitotic replication and division.

p53 plays an important role in triggering the control mechanisms at both G1/S and G2/M checkpoints. In addition to p53, checkpoint regulators are being heavily researched for their roles in cancer growth and proliferation.

Fluorescence imaging of the cell cycle

Pioneering work by Atsushi Miyawaki and coworkers developed the fluorescent ubiquitination-based cell cycle indicator (FUCCI), which enables fluorescence imaging of the cell cycle. Originally, a green fluorescent protein, mAG, was fused to hGem(1/110) and an orange fluorescent protein (mKO2) was fused to hCdt1(30/120). Note, these fusions are fragments that contain a nuclear localization signal and ubiquitination sites for degradation, but are not functional proteins. The green fluorescent protein is made during the S, G2, or M phase and degraded during the G0 or G1 phase, while the orange fluorescent protein is made during the G0 or G1 phase and destroyed during the S, G2, or M phase. A far-red and near-infrared FUCCI was developed using a cyanobacteria-derived fluorescent protein (smURFP) and a bacteriophytochrome-derived fluorescent protein (movie found at this link).

Role in tumor formation

A disregulation of the cell cycle components may lead to tumor formation. As mentioned above, when some genes like the cell cycle inhibitors, RB, p53 etc. mutate, they may cause the cell to multiply uncontrollably, forming a tumor. Although the duration of cell cycle in tumor cells is equal to or longer than that of normal cell cycle, the proportion of cells that are in active cell division (versus quiescent cells in G0 phase) in tumors is much higher than that in normal tissue. Thus there is a net increase in cell number as the number of cells that die by apoptosis or senescence remains the same.

The cells which are actively undergoing cell cycle are targeted in cancer therapy as the DNA is relatively exposed during cell division and hence susceptible to damage by drugs or radiation. This fact is made use of in cancer treatment; by a process known as debulking, a significant mass of the tumor is removed which pushes a significant number of the remaining tumor cells from G0 to G1 phase (due to increased availability of nutrients, oxygen, growth factors etc.). Radiation or chemotherapy following the debulking procedure kills these cells which have newly entered the cell cycle.

The fastest cycling mammalian cells in culture, crypt cells in the intestinal epithelium, have a cycle time as short as 9 to 10 hours. Stem cells in resting mouse skin may have a cycle time of more than 200 hours. Most of this difference is due to the varying length of G1, the most variable phase of the cycle. M and S do not vary much.

In general, cells are most radiosensitive in late M and G2 phases and most resistant in late S phase.

For cells with a longer cell cycle time and a significantly long G1 phase, there is a second peak of resistance late in G1.

The pattern of resistance and sensitivity correlates with the level of sulfhydryl compounds in the cell. Sulfhydryls are natural substances that protect cells from radiation damage and tend to be at their highest levels in S and at their lowest near mitosis.

Homologous recombination (HR) is an accurate process for repairing DNA double-strand breaks. HR is nearly absent in G1 phase, is most active in S phase, and declines in G2/M. Non-homologous end joining, a less accurate and more mutagenic process for repairing double strand breaks, is active throughout the cell cycle.