Nonhuman religious behaviour

Humanity's closest living relatives are common chimpanzees and bonobos.[1][2] These primates share a common ancestor with humans who lived between six and eight million years ago. It is for this reason that chimpanzees and bonobos are viewed as the best available surrogate for this common ancestor. Barbara King argues that while non-human primates are not religious, they do exhibit some traits that would have been necessary for the evolution of religion. These traits include high intelligence, a capacity for symbolic communication, a sense of social norms, realization of "self" and a concept of continuity.[3][4] There is inconclusive evidence that Homo neanderthalensis may have buried their dead which is evidence of the use of ritual. The use of burial rituals is thought to be evidence of religious activity, and there is no other evidence that religion existed in human culture before humans reached behavioral modernity.[5]Elephants demonstrate rituals around their deceased, which includes long periods of silence and mourning at the point of death and a process of returning to grave sites and caressing the remains.[6][7] Some evidence suggests that many species grieve death and loss.[8]

Setting the stage for human religion

Increased brain size

In this set of theories, the religious mind is one consequence of a brain that is large enough to formulate religious and philosophical ideas.[9] During human evolution, the hominid brain tripled in size, peaking 500,000 years ago. Much of the brain's expansion took place in the neocortex. The cerebral neocortex is presumed to be responsible for the neuronal computations underlying complex phenomena such as perception, thought, language, attention, episodic memory and voluntary movement.[10] According to Dunbar's theory, the relative neocortex size of any species correlates with the level of social complexity of the particular species.[11] The neocortex size correlates with a number of social variables that include social group size and complexity of mating behaviors.[12] In chimpanzees the neocortex occupies 50% of the brain, whereas in modern humans it occupies 80% of the brain.[13]Robin Dunbar argues that the critical event in the evolution of the neocortex took place at the speciation of archaic homo sapiens about 500,000 years ago. His study indicates that only after the speciation event is the neocortex large enough to process complex social phenomena such as language and religion. The study is based on a regression analysis of neocortex size plotted against a number of social behaviors of living and extinct hominids.[14]

Stephen Jay Gould suggests that religion may have grown out of evolutionary changes which favored larger brains as a means of cementing group coherence among savannah hunters, after that larger brain enabled reflection on the inevitability of personal mortality.[15]

Tool use

Lewis Wolpert argues that causal beliefs that emerged from tool use played a major role in the evolution of belief. The manufacture of complex tools requires creating a mental image of an object which does not exist naturally before actually making the artifact. Furthermore, one must understand how the tool would be used, that requires an understanding of causality.[16] Accordingly, the level of sophistication of stone tools is a useful indicator of causal beliefs.[17] Wolpert contends use of tools composed of more than one component, such as hand axes, represents an ability to understand cause and effect. However, recent studies of other primates indicate that causality may not be a uniquely human trait. For example, chimpanzees have been known to escape from pens closed with multiple latches, which was previously thought could only have been figured out by humans who understood causality. Chimpanzees are also known to mourn the dead, and notice things that have only aesthetic value, like sunsets, both of which may be considered to be components of religion or spirituality.[18] The difference between the comprehension of causality by humans and chimpanzees is one of degree. The degree of comprehension in an animal depends upon the size of the prefrontal cortex: the greater the size of the prefrontal cortex the deeper the comprehension.[19]Development of language

Religion requires a system of symbolic communication, such as language, to be transmitted from one individual to another. Philip Lieberman states "human religious thought and moral sense clearly rest on a cognitive-linguistic base".[20] From this premise science writer Nicholas Wade states:- "Like most behaviors that are found in societies throughout the world, religion must have been present in the ancestral human population before the dispersal from Africa 50,000 years ago. Although religious rituals usually involve dance and music, they are also very verbal, since the sacred truths have to be stated. If so, religion, at least in its modern form, cannot pre-date the emergence of language. It has been argued earlier that language attained its modern state shortly before the exodus from Africa. If religion had to await the evolution of modern, articulate language, then it too would have emerged shortly before 50,000 years ago."[21]

Morality and group living

Frans de Waal and Barbara King both view human morality as having grown out of primate sociality. Though morality awareness may be a unique human trait, many social animals, such as primates, dolphins and whales, have been known to exhibit pre-moral sentiments. According to Michael Shermer, the following characteristics are shared by humans and other social animals, particularly the great apes:- "attachment and bonding, cooperation and mutual aid, sympathy and empathy, direct and indirect reciprocity, altruism and reciprocal altruism, conflict resolution and peacemaking, deception and deception detection, community concern and caring about what others think about you, and awareness of and response to the social rules of the group".[22]

All social animals have hierarchical societies in which each member knows its own place. Social order is maintained by certain rules of expected behavior and dominant group members enforce order through punishment. However, higher order primates also have a sense of fairness. In a 2008 study, de Waal and colleagues put two capuchin monkeys side by side and gave them a simple task to complete: Giving a rock to the experimenter. They were given cucumbers as a reward for executing the task, and the monkeys obliged. But if one of the monkeys was given grapes, something interesting happened: After receiving the first piece of cucumber, the capuchin monkey gave the experimenter a rock as expected. But upon seeing that the other monkey got grapes, the capuchin monkey threw away the next piece of cucumber that was given to him.[23]

Chimpanzees live in fission-fusion groups that average 50 individuals. It is likely that early ancestors of humans lived in groups of similar size. Based on the size of extant hunter-gatherer societies, recent Paleolithic hominids lived in bands of a few hundred individuals. As community size increased over the course of human evolution, greater enforcement to achieve group cohesion would have been required. Morality may have evolved in these bands of 100 to 200 people as a means of social control, conflict resolution and group solidarity. According to Dr. de Waal, human morality has two extra levels of sophistication that are not found in primate societies. Humans enforce their society's moral codes much more rigorously with rewards, punishments and reputation building. Humans also apply a degree of judgment and reason not otherwise seen in the animal kingdom.

Psychologist Matt J. Rossano argues that religion emerged after morality and built upon morality by expanding the social scrutiny of individual behavior to include supernatural agents. By including ever-watchful ancestors, spirits and gods in the social realm, humans discovered an effective strategy for restraining selfishness and building more cooperative groups.[24] The adaptive value of religion would have enhanced group survival.[25][26] Rossano is referring here to collective religious belief and the social sanction that institutionalized morality. According to Rossano's teaching, individual religious belief is thus initially epistemological, not ethical, in nature.

Evolutionary psychology of religion

Cognitive scientists underlined that religions may be explained as a result of the brain architecture that expressed in early Homo genus, through the history of life. However, there is disagreement on the exact mechanisms that drove the evolution of the religious mind. The two main schools of thought hold that either religion evolved due to natural selection and has selective advantage, or that religion is an evolutionary byproduct of other mental adaptations.[27] Stephen Jay Gould, for example, believed that religion was an exaptation or a spandrel, in other words that religion evolved as byproduct of psychological mechanisms that evolved for other reasons.[28][29][30]Such mechanisms may include the ability to infer the presence of organisms that might do harm (agent detection), the ability to come up with causal narratives for natural events (etiology), and the ability to recognize that other people have minds of their own with their own beliefs, desires and intentions (theory of mind). These three adaptations (among others) allow human beings to imagine purposeful agents behind many observations that could not readily be explained otherwise, e.g. thunder, lightning, movement of planets, complexity of life.[31] The emergence of collective religious belief identified the agents as deities that standardized the explanation.[32]

Some scholars have suggested that religion is genetically "hardwired" into the human condition. One controversial proposal, the God gene hypothesis, states that some variants of a specific gene, the VMAT2 gene, predispose to spirituality.[33]

Another view is based on the concept of the triune brain: the reptilian brain, the limbic system, and the neocortex, proposed by Paul D. MacLean. Collective religious belief draws upon the emotions of love, fear, and gregariousness and is deeply embedded in the limbic system through socio-biological conditioning and social sanction. Individual religious belief utilizes reason based in the neocortex and often varies from collective religion. The limbic system is much older in evolutionary terms than the neocortex and is, therefore, stronger than it much in the same way as the reptilian is stronger than both the limbic system and the neocortex.

Yet another view is that the behavior of people who participate in a religion makes them feel better and this improves their fitness, so that there is a genetic selection in favor of people who are willing to believe in religion. Specifically, rituals, beliefs, and the social contact typical of religious groups may serve to calm the mind (for example by reducing ambiguity and the uncertainty due to complexity) and allow it to function better when under stress.[34] This would allow religion to be used as a powerful survival mechanism, particularly in facilitating the evolution of hierarchies of warriors, which if true, may be why many modern religions tend to promote fertility and kinship.

Still another view, proposed by F.H. Previc, is that human religion was a product of an increase in dopaminergic functions in the human brain and a general intellectual expansion beginning around 80 kya.[35][36][37] Dopamine promotes an emphasis on distant space and time, which is critical for the establishment of religious experience.[38] While the earliest shamanic cave paintings date back around 40 kya, the use of ochre for rock art predates this and there is clear evidence for abstract thinking along the coast of South Africa 80 kya.

Prehistoric evidence of religion

The exact time when humans first became religious remains unknown, however research in evolutionary archaeology shows credible evidence of religious-cum-ritualistic behaviour from around the Middle Paleolithic era (45-200 thousand years ago).[39]Paleolithic burials

The earliest evidence of religious thought is based on the ritual treatment of the dead. Most animals display only a casual interest in the dead of their own species.[40] Ritual burial thus represents a significant change in human behavior. Ritual burials represent an awareness of life and death and a possible belief in the afterlife. Philip Lieberman states "burials with grave goods clearly signify religious practices and concern for the dead that transcends daily life."[20]The earliest evidence for treatment of the dead comes from Atapuerca in Spain. At this location the bones of 30 individuals believed to be Homo heidelbergensis have been found in a pit.[41] Neanderthals are also contenders for the first hominids to intentionally bury the dead. They may have placed corpses into shallow graves along with stone tools and animal bones. The presence of these grave goods may indicate an emotional connection with the deceased and possibly a belief in the afterlife. Neanderthal burial sites include Shanidar in Iraq and Krapina in Croatia and Kebara Cave in Israel.[42][43][43][44]

The earliest known burial of modern humans is from a cave in Israel located at Qafzeh. Human remains have been dated to 100,000 years ago. Human skeletons were found stained with red ochre. A variety of grave goods were found at the burial site. The mandible of a wild boar was found placed in the arms of one of the skeletons.[45] Philip Lieberman states:

- "Burial rituals incorporating grave goods may have been invented by the anatomically modern hominids who emigrated from Africa to the Middle East roughly 100,000 years ago".[45]

Use of symbolism

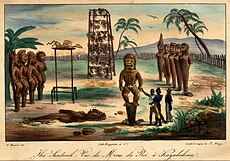

The use of symbolism in religion is a universal established phenomenon. Archeologist Steven Mithen contends that it is common for religious practices to involve the creation of images and symbols to represent supernatural beings and ideas. Because supernatural beings violate the principles of the natural world, there will always be difficulty in communicating and sharing supernatural concepts with others. This problem can be overcome by anchoring these supernatural beings in material form through representational art. When translated into material form, supernatural concepts become easier to communicate and understand.[47] Due to the association of art and religion, evidence of symbolism in the fossil record is indicative of a mind capable of religious thoughts. Art and symbolism demonstrates a capacity for abstract thought and imagination necessary to construct religious ideas. Wentzel van Huyssteen states that the translation of the non-visible through symbolism enabled early human ancestors to hold beliefs in abstract terms.[48]Some of the earliest evidence of symbolic behavior is associated with Middle Stone Age sites in Africa. From at least 100,000 years ago, there is evidence of the use of pigments such as red ochre. Pigments are of little practical use to hunter gatherers, thus evidence of their use is interpreted as symbolic or for ritual purposes. Among extant hunter gatherer populations around the world, red ochre is still used extensively for ritual purposes. It has been argued that it is universal among human cultures for the color red to represent blood, sex, life and death.[49]

The use of red ochre as a proxy for symbolism is often criticized as being too indirect. Some scientists, such as Richard Klein and Steven Mithen, only recognize unambiguous forms of art as representative of abstract ideas. Upper paleolithic cave art provides some of the most unambiguous evidence of religious thought from the paleolithic. Cave paintings at Chauvet depict creatures that are half human and half animal.

Origins of organized religion

Organised religion traces its roots to the neolithic revolution that began 11,000 years ago in the Near East but may have occurred independently in several other locations around the world. The invention of agriculture transformed many human societies from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to a sedentary lifestyle. The consequences of the neolithic revolution included a population explosion and an acceleration in the pace of technological development. The transition from foraging bands to states and empires precipitated more specialized and developed forms of religion that reflected the new social and political environment. While bands and small tribes possess supernatural beliefs, these beliefs do not serve to justify a central authority, justify transfer of wealth or maintain peace between unrelated individuals. Organized religion emerged as a means of providing social and economic stability through the following ways:- Justifying the central authority, which in turn possessed the right to collect taxes in return for providing social and security services.

- Bands and tribes consist of small number of related individuals. However, states and nations are composed of many thousands of unrelated individuals. Jared Diamond argues that organized religion served to provide a bond between unrelated individuals who would otherwise be more prone to enmity. In his book Guns, Germs, and Steel he argues that the leading cause of death among hunter-gatherer societies is murder.[50]

- Religions that revolved around moralizing gods may have facilitated the rise of large, cooperative groups of unrelated individuals.[51]