| Denali National Park and Preserve | |

|---|---|

IUCN category V (protected landscape/seascape)

| |

Denali is the tallest peak in North America

| |

| Location | Denali Borough and Matanuska-Susitna Borough, Alaska, United States |

| Nearest city | Healy |

| Coordinates | 63°20′N 150°30′WCoordinates: 63°20′N 150°30′W |

| Area | 4,740,911 acres (19,185.79 km2) (park) and 1,304,242 acres (5,278.08 km2) (preserve) |

| Established | February 26, 1917 |

| Visitors | 594,660 (in 2018) |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Official website |

Denali National Park and Preserve is an American national park and preserve located in Interior Alaska, centered on Denali, the highest mountain in North America. The park and contiguous preserve encompass 6,045,153 acres (9,446 sq mi; 24,464 km2) which is larger than the state of New Hampshire. On December 2, 1980, 2,146,580-acre (3,354 sq mi; 8,687 km2) Denali Wilderness was established within the park. Denali's landscape is a mix of forest at the lowest elevations, including deciduous taiga, with tundra at middle elevations, and glaciers, snow, and bare rock at the highest elevations. The longest glacier is the Kahiltna Glacier. Wintertime activities include dog sledding, cross-country skiing, and snowmobiling. The park received 594,660 recreational visitors in 2018.

History

Prehistory and protohistory

Human

habitation in the Denali Region extends to more than 11,000 years

before the present, with documented sites just outside park boundaries

dated to more than 8,000 years before present. However, relatively few

archaeological sites have been documented within the park boundaries,

owing to the region's high elevation, with harsh winter conditions and

scarce resources compared to lower elevations in the area. The oldest

site within park boundaries is the Teklanika River site, dated to about

7130 BC. More than 84 archaeological sites have been documented within

the park. The sites are typically characterized as hunting camps rather

than settlements, and provide little cultural context. The presence of Athabaskan

peoples in the region is dated to 1,500 - 1,000 years before present on

linguistic and archaeological evidence, while researchers have proposed

that Athabaskans may have inhabited the area for thousands of years

before then. The principal groups in the park area in the last 500 years

include the Koyukon, Tanana and Dena'ina people.

Establishment of the park

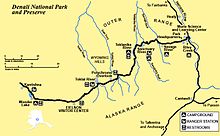

Park map

In 1906, conservationist Charles Alexander Sheldon conceived the idea of preserving the Denali region as a national park. He presented the plan to his co-members of the Boone and Crockett Club.

They decided that the political climate at the time was unfavorable for

congressional action, and that the best hope of success rested on the

approval and support from the Alaskans themselves. Sheldon wrote, "The

first step was to secure the approval and cooperation of the delegate

who represented Alaska in Congress."

In October 1915, Sheldon took up the matter with Dr. E. W. Nelson of the Biological Survey at Washington, D.C. and with George Bird Grinnell,

with a purpose to introduce a suitable bill in the coming session of

Congress. The matter was then taken to the Game Committee of the Boone and Crockett Club and, after a full discussion, it received the committee's full endorsement.

On December 3, 1915, the plan was presented to Alaska's delegate, James Wickersham, who after some deliberation gave his approval. The plan then went to the Executive Committee of the Boone and Crockett Club and, on December 15, 1915, it was unanimously accepted. The plan was thereupon endorsed by the Club and presented to Stephen Mather, Assistant Secretary of the Interior in Washington, D.C., who immediately approved it.

The bill was introduced in April 1916, by Delegate Wickersham in the House and by Senator Key Pittman

of Nevada in the Senate. Much lobbying took place over the following

year, and on February 19, 1917, the bill passed. On February 26, 1917,

11 years from its conception, the bill was signed in legislation by the

President of the United States, Woodrow Wilson, thereby creating Mount McKinley National Park.

A portion of Denali, excluding the summit, was included the

original park boundary. On Thanksgiving Day in 1921, the Mount McKinley

Park Hotel opened. In July 1923, President Warren Harding stopped at the hotel, on a tour of the length of the Alaska Railroad, during which he drove a golden spike signaling its completion at Nenana.

The hotel was the first thing visitors saw stepping down from the

train. The flat-roofed, two-story log building featured exposed

balconies, glass windows, and electric lights. Inside were two dozen

guest rooms, a shop, lunch counter, kitchen, and storeroom. By the

1930s, there were reports of lice, dirty linen, drafty rooms, and

marginal food, which led to the hotel's eventually closing.

In 1947, the park boundaries expanded to include the area of the

hotel and railroad. After being abandoned for many years, the hotel was

destroyed in 1950 by a fire.

There was no road access to the park entrance until 1957. Now

with a highway connection to Anchorage and Fairbanks, park attendance

greatly expanded: there were 5,000 visitors in 1956 and 25,000 visitors

by 1958.

Graphic of Denali Park History - Denali Visitor Center

The park was designated an international biosphere reserve in 1976. A separate Denali National Monument was proclaimed by President Jimmy Carter on December 1, 1978.

Naming controversy

Aerial view of Denali's summit

The name of Mount McKinley National Park was subject to local

criticism from the beginning of the park. The word Denali means "the

high one" in the native Athabaskan language and refers to the mountain itself. The mountain was named after newly elected US president William McKinley

in 1897 by local prospector William A. Dickey. The United States

government formally adopted the name Mount McKinley after President

Wilson signed the bill creating Mount McKinley National Park into effect

in 1917. In 1980, Mount McKinley National Park was combined with Denali National Monument, and the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act

named the combined unit the Denali National Park and Preserve. At that

time the Alaska state Board of Geographic Names changed the name of the

mountain to Denali. However, the U.S. Board on Geographic Names

did not recognize the change and continued to denote the official name

as Mount McKinley. This situation lasted until Aug. 30, 2015, when

President Barack Obama directed Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell

to rename the mountain to Denali, using statutory authority to act on

requests when the Board of Geographic Names does not do so in a

"reasonable" time period.

1990s

In 1992, Christopher McCandless ventured into the Alaskan wilderness and settled in an abandoned bus in the park, off the Stampede Trail, near Lake Wentitika. He carried little food or equipment, and hoped to live simply for a time in solitude. Almost four months later, McCandless' starved remains were found, weighing only 67 pounds (30 kg). His story has been widely publicized via articles, books, and films,

and the bus in which his remains were found has become a shrine of

sorts, attracting pilgrimages by people from around the world, many of

whom leave tributes in McCandless' memory.

2000s

On November 5, 2012, the United States Mint released the 15th of its America the Beautiful Quarters series, which honors Denali National Park. The coin's reverse side features a Dall sheep with Denali in the background.

In September 2013, President Barack Obama signed the Denali National Park Improvement Act into law. Hundreds, if not thousands of people had promoted the law and put it through Congress. The statute allows the United States Department of the Interior to "issue permits for microhydroelectric

projects in the Kantishna Hills area of the Denali National Park and

Preserve in Alaska"; it authorizes the Department of the Interior and a

company called Doyon Tourism, Inc. to exchange some land in the area; it

authorizes the National Park Service

(NPS) to "issue permits to construct a natural gas pipeline in the

Denali National Park"; and it renames the existing Talkeetna Ranger

Station the Walter Harper Talkeetna Ranger Station.

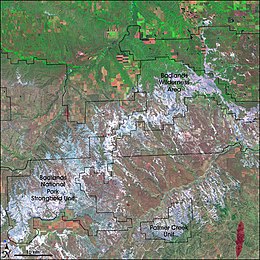

Geography

Denali National Park and Preserve includes the central, highest portion of the Alaska Range,

together with many of the glaciers and glacial valleys running

southwards out of the range. To the north the park and preserve

encompass the valleys of the McKinley, Toklat and Foraker Rivers, as well as the Kantishna and Wyoming Hills. The George Parks Highway runs along the eastern edge of the park, crossing the Alaska Range at the divide between the valleys of the Chultina River and the Nenana River. The entrance to the park is about 11 miles (18 km) south of Healy.

The Denali Visitor Center and the park headquarters are located just

inside the entrance. The park road parallels the Alaska Range for 92

miles (148 km), ending at Kantishna. Preserve lands are located on the

west side of the park, with one parcel encompassing areas of lakes in

the Highpower Creek and Muddy River areas, and the second preserve area

covering the southwest end of the high Alaska Range around Mount Dall.

In contrast to the park, where hunting is prohibited or restricted to

subsistence hunting by local residents, sport hunting is allowed in the

preserve lands.

Vehicle access

The single road within the park

The park is serviced by the 91-mile (146 km) long Denali Park Road, which begins at the George Parks Highway and continues to the west, ending at Kantishna.

Located 1 mile (1.6 km) within the park, the Wilderness Access Center

(which houses a small gift shop, a coffee stand, and an information

desk) is the main location to arrange a bus trip into the park, or

reserve/check-in for a campground site. All shuttle buses depart from

here, as do some tours. The Denali Visitor Center is at mile marker 1.5

on the park road and is the main source of visitor information. Most

ranger-led programs begin at the Denali Visitor Center. Other features

include an exhibit hall. Within a short walking distance from the

Visitor Center are a restaurant, a bookstore, the Murie Science and

Learning Center, the Denali National Park railroad depot, and the McKinley National Park Airport.

The Denali Park Road runs north of and roughly parallel to the imposing Alaska Range. Only a small fraction of the road is paved because permafrost and the freeze-thaw cycle

would create a high cost for maintaining a paved road. The first 15

miles (24 km) of the road are available to private vehicles, allowing

easy access to the Riley Creek and Savage River campgrounds. Private

vehicle access is prohibited beyond the Savage River Bridge. There is a

turn around for motorists at this point, as well as a nearby parking

area for those who wish to hike the Savage River Loop Trail. Beyond this

point, visitors must access the interior of the park through

tour/shuttle buses.

The tours travel from the initial boreal forests through tundra to the Toklat River or Kantishna. Several portions of the road run alongside sheer cliffs that drop hundreds of feet at the edges. There are no guardrails. As a result of the danger involved, and because most of the gravel road is only one lane wide, drivers must be trained in procedures for navigating the sharp mountain curves, and yielding the right-of-way to opposing buses and park vehicles.

Road map with camping locations, visitor centers, and ranger stations

There are four camping areas located within the interior of the park (Sanctuary River, Teklanika River, Igloo Creek, and Wonder Lake).

Camper buses provide transportation to these campgrounds, but only

passengers camping in the park can use these particular buses. At mile

marker 53 on road is the Toklat River Contact Station. All shuttle and

tour buses make a stop at Toklat River. The contact station features

rest rooms, visitor information, and a small bookstore. Eielson Visitor

Center is located four hours into the park on the road (at mile marker

66). It features restrooms, daily ranger-led programs during the summer,

and on clear days, views of Denali and the Alaska Range. Wonder Lake

and Kantishna are a six-hour bus ride from the Visitors Center. During

the winter, only the portion of the Denali Park Road near the Visitors

Center remains open.

Kantishna features five lodges: the Denali Backcountry Lodge,

Kantishna Roadhouse, Skyline Lodge, Camp Denali and North Face Lodge.

Visitors can bypass the six hour bus ride and charter an air taxi flight

to the Kantishna Airport. The Kantishna resorts have no TVs, and there is no cell phone service in the area. Lodging with services can be found in McKinley Park,

one mile north of the park entrance on the George Parks Highway. Many

hotels, restaurants, gift shops, and a convenience store are located in

Denali Park.

While the main park road goes straight through the middle of the

Denali National Park Wilderness, the national preserve and portions of

the park not designated wilderness

are even more inaccessible. There are no roads extending out to the

preserve areas, which are on the far west end of the park. The far north

of the park, characterized by hills and rivers, is accessed by the Stampede Trail,

a dirt road which effectively stops at the park boundary near the "Into

the Wild" bus. The rugged south portion of the park, characterized by

large glacier-filled canyons,

is accessed by Petersville Road, a dirt road that stops about 5 miles

(8.0 km) outside the park. The mountains can be accessed most easily by

air taxis that land on the glaciers. Kantishna can also be reached by

air taxi via the Purkeypile Airport, which is just outside the park

boundary.

Visitors who want to climb Denali

need to obtain a climbing permit first, and go through an orientation

as well. These can be found at the Walter Harper Talkeetna Ranger

Station in Talkeetna, Alaska,

about 100 miles (160 km) south of the entrance to Denali National Park

and Preserve. This center serves as the center of mountaineering

operations. It is open year-round.

Wilderness

Camping in the Savage River drainage

The Denali Wilderness is a wilderness area within Denali National

Park and Preserve that protects the higher elevations of the central Alaska Range, including Denali. The wilderness comprises about one-third of the current national park and preserve—2,146,580 acres (3,354 sq mi; 8,687 km2) that correspond with the former park boundaries from 1917 to 1980.

Geology

Geologic time scale and geologic map of terranes

Tectonic history

Denali from Ruth Glacier

Denali National Park and Preserve is located in the central area of

the Alaska Range, a mountain chain extending 600 miles (970 km) across

Alaska. Its best-known geologic feature is Denali,

formerly known as Mount McKinley. Its elevation of 20,310 feet

(6,190.5 m) makes it the highest mountain in North America. Its vertical

relief (distance from base to peak) of 18,000 feet (5,500 m) is the

highest of any mountain in the world. The mountain is still gaining

about 1 millimetre (0.039 in) in height each year due to the continued

convergence of the North American and Pacific Plates. The mountain is primarily made of granite, a hard rock that does not erode easily; this is why it has retained such a great height rather than being eroded.

The park area is characterized by collision tectonics: over the past millions of years, exotic terranes

in the Pacific Ocean have been moving toward the North American

landmass and accreting, or attaching, to the area that now makes up

Alaska. The oldest rocks in the park are part of the Yukon-Tanana

terrane. They originated from ocean sediments deposited between 400

million and 1 billion years ago. The original rocks have been affected

by the processes of regional metamorphism, folding, and faulting to form

rocks such as schist, quartzite, phyllite, slate, marble, and limestone. The next oldest group of rocks is the Farewell terrane. It is composed of rocks from the Paleozoic era

(250-500 million years old). The sediments that make up these rocks

were deposited in a variety of marine environments, ranging from deep

ocean basins to continental shelf areas. The abundant marine fossils are

evidence that around 380 million years ago, this area had a warm,

tropical climate. The Pingston, McKinley, and Chulitna terranes are the

next oldest; they were deposited in the Mesozoic era. The rock types include marble, chert, limestone, shale, and sandstone. There are intrusions of igneous rocks, such as gabbro, diabase, and diorite. Special features include pillow basalts,

which are formed when molten lava flows into water and a hard outer

crust forms, making a puffy, pillow shaped feature; as well as an

ophiolite sequence, which is a distinct sequence of rocks indicating

that a section of oceanic crust has been uplifted and thrust onto a

continental area.

Polychrome Mountain

Some of the youngest rocks in the park include the Kahlitna terrane,

which is a flysch sequence (a sedimentary rock sequence deposited in a

marine environment during the early stages of mountain building) formed

about 100 million years ago, during late Cretaceous time. Another rock sequence is the McKinley Intrusive Sequence, which includes Denali. The Cantwell Volcanics include basalt and rhyolite flows, as well as ash deposits. An example can be seen at Polychrome Pass in the park.

Mesozoic fossils include fossil trackways from therizinosaurids and hadrosaurids in the Cantwell Formation indicate the area was once an immigration point for dinosaurs

traveling between Asia and North America during the Late Cretaceous

period. Studies of fossil plants from the same formation indicate the

area was wet, with marshes and ponds throughout the region.

Denali National Park and Preserve is located in an area of

intense tectonic activity: the Pacific Plate is subducting under the

North American plate, creating the Denali fault system, which is a right-lateral strike-slip fault over 720 miles (1,160 km) long. This is a part of the larger fault system which includes the famous San Andreas Fault

of California. Over 600 earthquakes occur in the park each year,

helping seismologists to understand this fault system. Most of these

earthquakes are too small to be felt, although two large earthquakes did

occur in 2002. On October 23, 2002 a magnitude 6.7 earthquake occurred

in the park, and on November 3, 2002, a magnitude 7.9 earthquake

occurred. These earthquakes did not cause a significant loss of life or

property, since the area is very sparsely populated, but they did

trigger thousands of landslides.

Painting

of the heavily glaciated southern part of Denali, looking

north-northwest. Mount Foraker is at the left, and Denali, purposely

drawn on an exaggerated scale, is featured in the center. Mouse over the

painting, and click on an area of interest.

Glaciers

The Kichatna Mountains in the southwestern portion of the preserve

Glaciers cover about 16% of the 6 million acres of Denali National

Park and Preserve. There are more extensive glaciers on the southeastern

side of the range because more snow is dropped on this side from the

moisture-bearing winds from the Gulf of Alaska. The 5 largest south-facing glaciers are Yentna (20 miles (32 km) long), Kahiltna (30 miles (48 km)), Tokositna (23 miles (37 km)), Ruth (31 miles (50 km)), and Eldrige (30 miles (48 km)). The Ruth glacier is 3,800 feet (1,200 m) thick.[18] However, the largest glacier, Muldrow Glacier

(32 miles (51 km) long), is located on the north side. Nonetheless, the

northern side has smaller and shorter glaciers overall. Muldrow glacier

has "surged"

twice in the last hundred years. Surging means that it has moved

forward for a short time at a greatly increased rate of speed, due to a

build-up of water between the bottom of the glacier and the bedrock

channel floating on the ice (due to hydrostatic pressure).

At the upper ends of Denali's glaciers are steep-walled semicircular basins called cirques.

Cirques form from freeze-thaw cycles of meltwater in the rocks above

the glacier, and by glacial erosion and mass wasting occurring under the

glacier. As cirques on the opposite sides of a ridge are cut deeper

into the divide, they form a narrow, sharp, serrated ridge called an arête. As the arête wears away from glacial ice breaking it down, the low point between cirques is called a col

(or if it is large, a pass). Cols are saddle-shaped depressions in the

ridge between cirques. A spire-like sharp peak, called a horn, is formed when cirques cut back into a mountaintop from three or four sides.

Glaciers deposit rock fragments, but the most notable of the

depositions are the erratics, which are large rock fragments carried

some distance from the source, found on glacial terraces and ridge tops

in many places throughout Denali. Headquarter erratics are made of

granite and can be the size of a house. Some erratics (like those from

the Yanert Valley) are located 30 miles (48 km) away from their original

location.

Ruth Glacier and medial moraine - the dark stripe of debris down the middle

Large amounts of rock debris are carried on, in, and beneath the ice

as the glaciers move downslope. Lateral moraines are created as debris

accumulates as low ridges of till that ride along the edge of the moving

glaciers. When lateral moraines adjacent to each other join, they create medial moraines, which are also carried down on the surface of the moving ice.

Braided meltwater streams heavily loaded with rock debris

continually shift and intertwine their channels over valley floors.

Valley trains are built up as streams drop quantities of poorly sorted

sediment. Valley trains are long, narrow accumulation of glacial

outwash, confined by valley walls.

Kettles

are formed when glacial retreat and melting is rapid, and blocks of ice

are still buried under till. When the ice under the till melts, the

till slumps in and forms depressions called kettles. When kettles fill

with water, they are known as kettle lakes. Kettle lakes are visible near the Polychrome Overlook, the Teklanika rest stop and near Wonder Lake.

Permafrost

During the very cold Pleistocene

climates, all of Denali was solidly frozen. In the northern areas of

the range, it is very much still frozen due to continued cold

temperatures. Permanently frozen ground is known as permafrost.

In Denali, the permafrost is discontinuous, meaning due to difference

in vegetation, temperatures, snow cover, hydrology, etc., not all of the

ground is solidly frozen. The active layer (the layer that freezes and

thaws seasonally) can be from 1 inch (25 mm) to 10 feet (3.0 m) thick.

The permafrost layer below the active layer has been measured to be

between 30 and 100 feet (9.1 and 30.5 m) deep depending on the location

of measurement in the park. A stand of white spruce growing on a lower

slope of Denali is called the Drunken Forest

because of the oddly leaning trees which seem to look "drunk." This

appearance is due to the sliding soil beneath them, due to the

permafrost difference and freeze-thaw oscillations that occur due to

differences in temperature, vegetation, and hydrology.

Shallow ponds in Denali are known as thaw lakes and cave-in

lakes. They form where sunwarmed water has melted basins in the

underlying permafrost. They deepen gradually in the summer months

depending on the temperature variance. If the temperature is high

enough, the thaw lakes and cave-in lakes will enlarge as their rims

collapse.

Ice has 10 percent greater volume than water, so it continues to

exert pressure on the ground. Thermal expansion and contraction can

cause cracks to develop in the permafrost. During the thaw season in the

freeze-thaw cycle, water gets into the cracks and forms veins of ice

called ice wedges. Ice wedges enlarge with successive seasons of

freezing and thawing. Some ice wedges that have been buried for

centuries are revealed during excavations or landslides.

Climate

According to the Köppen climate classification system, Denali National Park has a Subarctic with Cool Summers and Year Around Rainfall Climate (‘’Dfc’’). The plant hardiness zone at Denali Visitor Center is 3a with an average annual extreme minimum temperature of -38.9 °F (-39.4 °C).

Long winters are followed by short growing seasons. Eighty

percent of the bird population returns after cold months, raising their

young. Most mammals and other wildlife in the park spend the brief

summer months preparing for winter and raising their young.

Summers are usually cool and damp, but temperatures in the 70s

are not rare. The weather is so unpredictable that there have even been

instances of snow in August.

The north and south side of the Alaskan Range have a completely different climate. The Gulf of Alaska

carries moisture to the south side, but the mountains block water to

the north side. This brings a drier climate and huge temperature

fluctuations to the north. The south has transitional maritime

continental climates, with moister, cooler summers and warmer winters.

Ecology

Alpine forest and lakes in Denali

The Alaska Range

is a mountainous expanse running through the entire park, strongly

influencing the park's ecosystems. Vegetation in the park depends on the

altitude. The treeline is at 2,500 feet (760 m), causing most of the park to be a vast expanse of tundra. In the lowland areas of the park, such as the western sections surrounding Wonder Lake, spruces and willows

dominate the forest. Most trees and shrubs do not reach full size, due

to unfavorable climate and thin soils. There are three types of forest

in the park: from lowest to highest, they are low brush bog, bottomland spruce-poplar forest, upland spruce-hardwood forest. The forest grows in a mosaic, due to periodic fires.

In the tundra of the park, layers of topsoil collect on rotten fragmented rock moved by thousands of years of glacial activity. Mosses, ferns, grasses, and fungi grow on the topsoil. In areas of muskeg, tussocks form and may collect algae. The term 'muskeg' includes spongy waterlogged tussocks as well as deep pools of water covered by solid-looking moss. Wild blueberries and soap berries thrive in the tundra and provide the bears of Denali with the main part of their diet.

Over 450 species of flowering plants fill the park and can be viewed in bloom throughout summer. Images of goldenrod, fireweed, lupine, bluebell, and gentian filling the valleys of Denali are often used on postcards and in artwork.

Adult brown bear (Ursus arctos) and cub on the park road

Denali is home to a variety of North American birds and mammals, including an estimated 300-350 grizzly bears on the north side of the Alaska Range (70 bears per 1000 square miles) and an estimated 2,700 black bears (334 per 1,000 square miles). As of 2014, park biologists were monitoring about 51 wolves in 13 packs (7.4 wolves per 1,000 square miles), while surveys estimated 2,230 caribou in 2013, and 1,477 moose in 2011. Dall sheep are often seen on mountainsides. Smaller animals such as coyotes, hoary marmots, shrews, Arctic ground squirrels, beavers, pikas, and snowshoe hares are seen in abundance. Red foxes, martens, lynxes, wolverines also inhabit the park, but are more rarely seen due to their elusive natures.

Many migratory bird species reside in the park during late spring and summer. There are waxwings, Arctic warblers, pine grosbeaks, and wheatears, as well as ptarmigan and the tundra swan. Raptors include a variety of hawks, owls, and gyrfalcons, as well as the abundant but striking golden eagles.

A caribou and tour bus on the park road

Ten species of fish, including trout, salmon, and Arctic grayling,

share the waters of the park. Because many of the rivers and lakes of

Denali are fed by glaciers, glacial silt and cold temperatures slow the

metabolism of the fish, preventing them from reaching normal sizes. A single amphibious species, the wood frog, also lives among the lakes of the park.

Denali park rangers maintain a constant effort to keep the

wildlife wild by limiting the interaction between humans and park

animals. Feeding any animal is strictly forbidden, as it may cause

adverse effects on the feeding habits of the creature. Visitors are

encouraged to view animals from safe distances. In August 2012 the park

experienced its first known fatal bear attack when a lone hiker

apparently startled a large male grizzly while photographing it.

Analysis of the scene and the hiker's camera strongly suggest he

violated park regulations regarding backcountry bear encounters, which

all permit holders are made aware of.

Certain areas of the park are often closed due to uncommon wildlife

activity, such as denning areas of wolves and bears or recent kill

sites.

Panoramic view of the Polychrome Mountains