A crystal is a solid material whose constituent atoms, molecules, or ions are arranged in an orderly repeating pattern extending in all three spatial dimensions. Crystal growth is a major stage of a crystallization process, and consists of the addition of new atoms, ions, or polymer strings into the characteristic arrangement of the crystalline lattice. The growth typically follows an initial stage of either homogeneous or heterogeneous (surface catalyzed) nucleation, unless a "seed" crystal, purposely added to start the growth, was already present.

The action of crystal growth yields a crystalline solid whose atoms or molecules are close packed, with fixed positions in space relative to each other. The crystalline state of matter is characterized by a distinct structural rigidity and very high resistance to deformation (i.e. changes of shape and/or volume). Most crystalline solids have high values both of Young's modulus and of the shear modulus of elasticity. This contrasts with most liquids or fluids, which have a low shear modulus, and typically exhibit the capacity for macroscopic viscous flow.

Overview

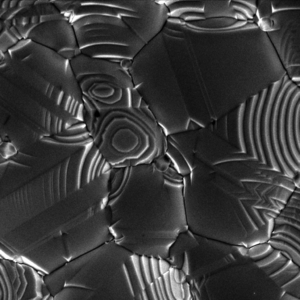

After successful formation of a stable nucleus, a growth stage ensues in which free particles (atoms or molecules) adsorb onto the nucleus and propagate its crystalline structure outwards from the nucleating site. This process is significantly faster than nucleation. The reason for such rapid growth is that real crystals contain dislocations and other defects, which act as a catalyst for the addition of particles to the existing crystalline structure. By contrast, perfect crystals (lacking defects) would grow exceedingly slowly. On the other hand, impurities can act as crystal growth inhibitors and can also modify crystal habit.

Nucleation

Nucleation can be either homogeneous, without the influence of foreign particles, or heterogeneous, with the influence of foreign particles. Generally, heterogeneous nucleation takes place more quickly since the foreign particles act as a scaffold for the crystal to grow on, thus eliminating the necessity of creating a new surface and the incipient surface energy requirements.

Heterogeneous nucleation can take place by several methods. Some of the most typical are small inclusions, or cuts, in the container the crystal is being grown on. This includes scratches on the sides and bottom of glassware. A common practice in crystal growing is to add a foreign substance, such as a string or a rock, to the solution, thereby providing nucleation sites for facilitating crystal growth and reducing the time to fully crystallize.

The number of nucleating sites can also be controlled in this manner. If a brand-new piece of glassware or a plastic container is used, crystals may not form because the container surface is too smooth to allow heterogeneous nucleation. On the other hand, a badly scratched container will result in many lines of small crystals. To achieve a moderate number of medium-sized crystals, a container which has a few scratches works best. Likewise, adding small previously made crystals, or seed crystals, to a crystal growing project will provide nucleating sites to the solution. The addition of only one seed crystal should result in a larger single crystal.

Mechanisms of growth

The interface between a crystal and its vapor can be molecularly sharp at temperatures well below the melting point. An ideal crystalline surface grows by the spreading of single layers, or equivalently, by the lateral advance of the growth steps bounding the layers. For perceptible growth rates, this mechanism requires a finite driving force (or degree of supercooling) in order to lower the nucleation barrier sufficiently for nucleation to occur by means of thermal fluctuations. In the theory of crystal growth from the melt, Burton and Cabrera have distinguished between two major mechanisms:

Non-uniform lateral growth

The surface advances by the lateral motion of steps which are one interplanar spacing in height (or some integral multiple thereof). An element of surface undergoes no change and does not advance normal to itself except during the passage of a step, and then it advances by the step height. It is useful to consider the step as the transition between two adjacent regions of a surface which are parallel to each other and thus identical in configuration—displaced from each other by an integral number of lattice planes. Note here the distinct possibility of a step in a diffuse surface, even though the step height would be much smaller than the thickness of the diffuse surface.

Uniform normal growth

The surface advances normal to itself without the necessity of a stepwise growth mechanism. This means that in the presence of a sufficient thermodynamic driving force, every element of surface is capable of a continuous change contributing to the advancement of the interface. For a sharp or discontinuous surface, this continuous change may be more or less uniform over large areas for each successive new layer. For a more diffuse surface, a continuous growth mechanism may require changes over several successive layers simultaneously.

Non-uniform lateral growth is a geometrical motion of steps—as opposed to motion of the entire surface normal to itself. Alternatively, uniform normal growth is based on the time sequence of an element of surface. In this mode, there is no motion or change except when a step passes via a continual change. The prediction of which mechanism will be operative under any set of given conditions is fundamental to the understanding of crystal growth. Two criteria have been used to make this prediction:

Whether or not the surface is diffuse: a diffuse surface is one in which the change from one phase to another is continuous, occurring over several atomic planes. This is in contrast to a sharp surface for which the major change in property (e.g. density or composition) is discontinuous, and is generally confined to a depth of one interplanar distance.

Whether or not the surface is singular: a singular surface is one in which the surface tension as a function of orientation has a pointed minimum. Growth of singular surfaces is known to requires steps, whereas it is generally held that non-singular surfaces can continuously advance normal to themselves.

Driving force

Consider next the necessary requirements for the appearance of lateral growth. It is evident that the lateral growth mechanism will be found when any area in the surface can reach a metastable equilibrium in the presence of a driving force. It will then tend to remain in such an equilibrium configuration until the passage of a step. Afterward, the configuration will be identical except that each part of the step but will have advanced by the step height. If the surface cannot reach equilibrium in the presence of a driving force, then it will continue to advance without waiting for the lateral motion of steps.

Thus, Cahn concluded that the distinguishing feature is the ability of the surface to reach an equilibrium state in the presence of the driving force. He also concluded that for every surface or interface in a crystalline medium, there exists a critical driving force, which, if exceeded, will enable the surface or interface to advance normal to itself, and, if not exceeded, will require the lateral growth mechanism.

Thus, for sufficiently large driving forces, the interface can move uniformly without the benefit of either a heterogeneous nucleation or screw dislocation mechanism. What constitutes a sufficiently large driving force depends upon the diffuseness of the interface, so that for extremely diffuse interfaces, this critical driving force will be so small that any measurable driving force will exceed it. Alternatively, for sharp interfaces, the critical driving force will be very large, and most growth will occur by the lateral step mechanism.

Note that in a typical solidification or crystallization process, the thermodynamic driving force is dictated by the degree of supercooling.

Morphology

It is generally believed that the mechanical and other properties of the crystal are also pertinent to the subject matter, and that crystal morphology provides the missing link between growth kinetics and physical properties. The necessary thermodynamic apparatus was provided by Josiah Willard Gibbs' study of heterogeneous equilibrium. He provided a clear definition of surface energy, by which the concept of surface tension is made applicable to solids as well as liquids. He also appreciated that an anisotropic surface free energy implied a non-spherical equilibrium shape, which should be thermodynamically defined as the shape which minimizes the total surface free energy.

It may be instructional to note that whisker growth provides the link between the mechanical phenomenon of high strength in whiskers and the various growth mechanisms which are responsible for their fibrous morphologies. (Prior to the discovery of carbon nanotubes, single-crystal whiskers had the highest tensile strength of any materials known). Some mechanisms produce defect-free whiskers, while others may have single screw dislocations along the main axis of growth—producing high strength whiskers.

The mechanism behind whisker growth is not well understood, but seems to be encouraged by compressive mechanical stresses including mechanically induced stresses, stresses induced by diffusion of different elements, and thermally induced stresses. Metal whiskers differ from metallic dendrites in several respects. Dendrites are fern-shaped like the branches of a tree, and grow across the surface of the metal. In contrast, whiskers are fibrous and project at a right angle to the surface of growth, or substrate.

Diffusion-control

Very commonly when the supersaturation (or degree of supercooling) is high, and sometimes even when it is not high, growth kinetics may be diffusion-controlled. Under such conditions, the polyhedral crystal form will be unstable, it will sprout protrusions at its corners and edges where the degree of supersaturation is at its highest level. The tips of these protrusions will clearly be the points of highest supersaturation. It is generally believed that the protrusion will become longer (and thinner at the tip) until the effect of interfacial free energy in raising the chemical potential slows the tip growth and maintains a constant value for the tip thickness.

In the subsequent tip-thickening process, there should be a corresponding instability of shape. Minor bumps or "bulges" should be exaggerated—and develop into rapidly growing side branches. In such an unstable (or metastable) situation, minor degrees of anisotropy should be sufficient to determine directions of significant branching and growth. The most appealing aspect of this argument, of course, is that it yields the primary morphological features of dendritic growth.