Giordano Bruno | |

|---|---|

Modern portrait based on a woodcut from "Livre du recteur", 1578 | |

| Born | Filippo Bruno January or February 1548 |

| Died | 17 February 1600 (aged 51–52) |

| Cause of death | Execution by burning at the stake |

| Era | Renaissance |

| School | Renaissance humanism Neopythagoreanism |

Main interests | Cosmology |

Notable ideas | Cosmic pluralism |

Influences | |

Influenced |

Giordano Bruno (/dʒɔːrˈdɑːnoʊ ˈbruːnoʊ/; Italian: [dʒorˈdaːno ˈbruːno]; Latin: Iordanus Brunus Nolanus; born Filippo Bruno, January or February 1548 – 17 February 1600) was an Italian philosopher, poet, cosmological theorist, and Hermetic occultist. He is known for his cosmological theories, which conceptually extended to include the then novel Copernican model. He proposed that the stars were distant suns surrounded by their own planets, and he raised the possibility that these planets might foster life of their own, a cosmological position known as cosmic pluralism. He also insisted that the universe is infinite and could have no "center".

While Bruno began as a Dominican friar, during his time in Geneva he embraced Calvinism. Bruno was later tried for heresy by the Roman Inquisition on charges of denial of several core Catholic doctrines, including eternal damnation, the Trinity, the divinity of Christ, the virginity of Mary, and transubstantiation. Bruno's pantheism was not taken lightly by the church, nor was his teaching of the transmigration of the soul (reincarnation). The Inquisition found him guilty, and he was burned alive at the stake in Rome's Campo de' Fiori in 1600. After his death, he gained considerable fame, being particularly celebrated by 19th- and early 20th-century commentators who regarded him as a martyr for science, although most historians agree that his heresy trial was not a response to his cosmological views but rather a response to his religious and afterlife views. Some historians contend that the main reason for Bruno's death was indeed his cosmological views. Bruno's case is still considered a landmark in the history of free thought and the emerging sciences.

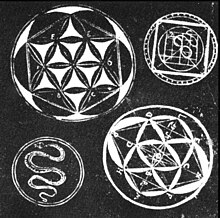

In addition to cosmology, Bruno also wrote extensively on the art of memory, a loosely organized group of mnemonic techniques and principles. Historian Frances Yates argues that Bruno was deeply influenced by the presocratic Empedocles, Neoplatonism, Renaissance Hermeticism, and Genesis-like legends surrounding the Hellenistic conception of Hermes Trismegistus. Other studies of Bruno have focused on his qualitative approach to mathematics and his application of the spatial concepts of geometry to language.

Life

Early years, 1548–1576

Born Filippo Bruno in Nola (a comune in the modern-day province of Naples, in the Southern Italian region of Campania, then part of the Kingdom of Naples) in 1548, he was the son of Giovanni Bruno, a soldier, and Fraulissa Savolino. In his youth he was sent to Naples to be educated. He was tutored privately at the Augustinian monastery there, and attended public lectures at the Studium Generale. At the age of 17, he entered the Dominican Order at the monastery of San Domenico Maggiore in Naples, taking the name Giordano, after Giordano Crispo, his metaphysics tutor. He continued his studies there, completing his novitiate, and ordained a priest in 1572 at age 24. During his time in Naples, he became known for his skill with the art of memory and on one occasion traveled to Rome to demonstrate his mnemonic system before Pope Pius V and Cardinal Rebiba. In his later years, Bruno claimed that the Pope accepted his dedication to him of the lost work On The Ark of Noah at this time.

While Bruno was distinguished for outstanding ability, his taste for free thinking and forbidden books soon caused him difficulties. Given the controversy he caused in later life, it is surprising that he was able to remain within the monastic system for eleven years. In his testimony to Venetian inquisitors during his trial many years later, he says that proceedings were twice taken against him for having cast away images of the saints, retaining only a crucifix, and for having recommended controversial texts to a novice. Such behavior could perhaps be overlooked, but Bruno's situation became much more serious when he was reported to have defended the Arian heresy, and when a copy of the banned writings of Erasmus, annotated by him, was discovered hidden in the monastery latrine. When he learned that an indictment was being prepared against him in Naples he fled, shedding his religious habit, at least for a time.

First years of wandering, 1576–1583

Bruno first went to the Genoese port of Noli, then to Savona, Turin and finally to Venice, where he published his lost work On the Signs of the Times with the permission (so he claimed at his trial) of the Dominican Remigio Nannini Fiorentino. From Venice he went to Padua, where he met fellow Dominicans who convinced him to wear his religious habit again. From Padua he went to Bergamo and then across the Alps to Chambéry and Lyon. His movements after this time are obscure.

In 1579 he arrived in Geneva. As D.W. Singer, a Bruno biographer, notes, "The question has sometimes been raised as to whether Bruno became a Protestant, and there is evidence he joined a Calvinist church. During his Venetian trial he told inquisitors that while in Geneva he told the Marchese de Vico of Naples, who was notable for helping Italian refugees in Geneva, "I did not intend to adopt the religion of the city. I desired to stay there only that I might live at liberty and in security." Bruno had a pair of breeches made for himself, and the Marchese and others apparently made Bruno a gift of a sword, hat, cape and other necessities for dressing himself; in such clothing Bruno could no longer be recognized as a priest. Things apparently went well for Bruno for a time, as he entered his name in the Rector's Book of the University of Geneva in May 1579. But in keeping with his personality he could not long remain silent. In August he published an attack on the work of Antoine de la Faye, a distinguished professor. Bruno and the printer, Jean Bergeon, were promptly arrested. Rather than apologizing, Bruno insisted on continuing to defend his publication. He was refused the right to take sacrament. Though this right was soon restored, he left Geneva.

He went to France, arriving first in Lyon, and thereafter settling for a time (1580–1581) in Toulouse, where he took his doctorate in theology and was elected by students to lecture in philosophy. He also attempted at this time to return to Catholicism, but was denied absolution by the Jesuit priest he approached. When religious strife broke out in the summer of 1581, he moved to Paris. There he held a cycle of thirty lectures on theological topics and also began to gain fame for his prodigious memory. His talents attracted the benevolent attention of the king Henry III; Bruno subsequently reported

"I got me such a name that King Henry III summoned me one day to discover from me if the memory which I possessed was natural or acquired by magic art. I satisfied him that it did not come from sorcery but from organized knowledge; and, following this, I got a book on memory printed, entitled The Shadows of Ideas, which I dedicated to His Majesty. Forthwith he gave me an Extraordinary Lectureship with a salary."

In Paris, Bruno enjoyed the protection of his powerful French patrons. During this period, he published several works on mnemonics, including De umbris idearum (On the Shadows of Ideas, 1582), Ars memoriae (The Art of Memory, 1582), and Cantus circaeus (Circe's Song, 1582; described at Circe in the arts § Reasoning beasts). All of these were based on his mnemonic models of organized knowledge and experience, as opposed to the simplistic logic-based mnemonic techniques of Petrus Ramus then becoming popular. Bruno also published a comedy summarizing some of his philosophical positions, titled Il Candelaio (The Torchbearer, 1582). In the 16th century dedications were, as a rule, approved beforehand, and hence were a way of placing a work under the protection of an individual. Given that Bruno dedicated various works to the likes of King Henry III, Sir Philip Sidney, Michel de Castelnau (French Ambassador to England), and possibly Pope Pius V, it is apparent that this wanderer had risen sharply in status and moved in powerful circles.

England, 1583–1585

In April 1583, Bruno went to England with letters of recommendation from Henry III as a guest of the French ambassador, Michel de Castelnau. Bruno lived at the French embassy with the lexicographer John Florio. There he became acquainted with the poet Philip Sidney (to whom he dedicated two books) and other members of the Hermetic circle around John Dee, though there is no evidence that Bruno ever met Dee himself. He also lectured at Oxford, and unsuccessfully sought a teaching position there. His views were controversial, notably with John Underhill, Rector of Lincoln College and subsequently bishop of Oxford, and George Abbot, who later became Archbishop of Canterbury. Abbot mocked Bruno for supporting "the opinion of Copernicus that the earth did go round, and the heavens did stand still; whereas in truth it was his own head which rather did run round, and his brains did not stand still", and found Bruno had both plagiarized and misrepresented Ficino's work, leading Bruno to return to the continent.

Nevertheless, his stay in England was fruitful. During that time Bruno completed and published some of his most important works, the six "Italian Dialogues", including the cosmological tracts La cena de le ceneri (The Ash Wednesday Supper, 1584), De la causa, principio et uno (On Cause, Principle and Unity, 1584), De l'infinito, universo et mondi (On the Infinite, Universe and Worlds, 1584) as well as Lo spaccio de la bestia trionfante (The Expulsion of the Triumphant Beast, 1584) and De gli eroici furori (On the Heroic Frenzies, 1585). Some of these were printed by John Charlewood. Some of the works that Bruno published in London, notably The Ash Wednesday Supper, appear to have given offense. Once again, Bruno's controversial views and tactless language lost him the support of his friends. John Bossy has advanced the theory that, while staying in the French Embassy in London, Bruno was also spying on Catholic conspirators, under the pseudonym "Henry Fagot", for Sir Francis Walsingham, Queen Elizabeth's Secretary of State.

Bruno is sometimes cited as being the first to propose that the universe is infinite, which he did during his time in England, but an English scientist, Thomas Digges, put forth this idea in a published work in 1576, some eight years earlier than Bruno. An infinite universe and the possibility of alien life had also been earlier suggested by German Catholic Cardinal Nicholas of Cusa in "On Learned Ignorance" published in 1440 and Bruno attributed his understanding of multiple worlds to this earlier scholar, who he called "the divine Cusanus".

Last years of wandering, 1585–1592

In October 1585, Castelnau was recalled to France, and Bruno went with him. In Paris, Bruno found a tense political situation. Moreover, his 120 theses against Aristotelian natural science soon put him in ill favor. In 1586, following a violent quarrel over these theses, he left France for Germany.

In Germany he failed to obtain a teaching position at Marburg, but was granted permission to teach at Wittenberg, where he lectured on Aristotle for two years. However, with a change of intellectual climate there, he was no longer welcome, and went in 1588 to Prague, where he obtained 300 taler from Rudolf II, but no teaching position. He went on to serve briefly as a professor in Helmstedt, but had to flee again in 1590 when he was excommunicated by the Lutherans.

During this period he produced several Latin works, dictated to his friend and secretary Girolamo Besler, including De Magia (On Magic), Theses De Magia (Theses on Magic) and De Vinculis in Genere (A General Account of Bonding). All these were apparently transcribed or recorded by Besler (or Bisler) between 1589 and 1590. He also published De Imaginum, Signorum, Et Idearum Compositione (On the Composition of Images, Signs and Ideas, 1591).

In 1591 he was in Frankfurt, where he received an invitation from the Venetian patrician Giovanni Mocenigo, who wished to be instructed in the art of memory, and also heard of a vacant chair in mathematics at the University of Padua. At the time the Inquisition seemed to be losing some of its strictness, and because the Republic of Venice was the most liberal state in the Italian Peninsula, Bruno was lulled into making the fatal mistake of returning to Italy.

He went first to Padua, where he taught briefly, and applied unsuccessfully for the chair of mathematics, which was given instead to Galileo Galilei one year later. Bruno accepted Mocenigo's invitation and moved to Venice in March 1592. For about two months he served as an in-house tutor to Mocenigo, to whom he let slip some of his heterodox ideas. Mocenigo denounced him to the Venetian Inquisition, which had Bruno arrested on 22 May 1592. Among the numerous charges of blasphemy and heresy brought against him in Venice, based on Mocenigo's denunciation, was his belief in the plurality of worlds, as well as accusations of personal misconduct. Bruno defended himself skillfully, stressing the philosophical character of some of his positions, denying others and admitting that he had had doubts on some matters of dogma. The Roman Inquisition, however, asked for his transfer to Rome. After several months of argument, the Venetian authorities reluctantly consented and Bruno was sent to Rome in January 1593.

Imprisonment, trial and execution, 1593–1600

During the seven years of his trial in Rome, Bruno was held in confinement, lastly in the Tower of Nona. Some important documents about the trial are lost, but others have been preserved, among them a summary of the proceedings that was rediscovered in 1940. The numerous charges against Bruno, based on some of his books as well as on witness accounts, included blasphemy, immoral conduct, and heresy in matters of dogmatic theology, and involved some of the basic doctrines of his philosophy and cosmology. Luigi Firpo speculates the charges made against Bruno by the Roman Inquisition were:

- holding opinions contrary to the Catholic faith and speaking against it and its ministers;

- holding opinions contrary to the Catholic faith about the Trinity, the divinity of Christ, and the Incarnation;

- holding opinions contrary to the Catholic faith pertaining to Jesus as the Christ;

- holding opinions contrary to the Catholic faith regarding the virginity of Mary, mother of Jesus;

- holding opinions contrary to the Catholic faith about both Transubstantiation and the Mass;

- claiming the existence of a plurality of worlds and their eternity;

- believing in metempsychosis and in the transmigration of the human soul into brutes;

- dealing in magics and divination.

Bruno defended himself as he had in Venice, insisting that he accepted the Church's dogmatic teachings, but trying to preserve the basis of his cosmological views. In particular, he held firm to his belief in the plurality of worlds, although he was admonished to abandon it. His trial was overseen by the Inquisitor Cardinal Bellarmine, who demanded a full recantation, which Bruno eventually refused. On 20 January 1600, Pope Clement VIII declared Bruno a heretic, and the Inquisition issued a sentence of death. According to the correspondence of Gaspar Schopp of Breslau, he is said to have made a threatening gesture towards his judges and to have replied: Maiori forsan cum timore sententiam in me fertis quam ego accipiam ("Perhaps you pronounce this sentence against me with greater fear than I receive it").

He was turned over to the secular authorities. On 17 February 1600, in the Campo de' Fiori (a central Roman market square), with his "tongue imprisoned because of his wicked words", he was hung upside down naked before finally being burned alive at the stake. His ashes were thrown into the Tiber river.

All of Bruno's works were placed on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum in 1603. The inquisition cardinals who judged Giordano Bruno were Cardinal Bellarmino (Bellarmine), Cardinal Madruzzo (Madruzzi), Camillo Cardinal Borghese (later Pope Paul V), Domenico Cardinal Pinelli, Pompeio Cardinal Arrigoni, Cardinal Sfondrati, Pedro Cardinal De Deza Manuel and Cardinal Santorio (Archbishop of Santa Severina, Cardinal-Bishop of Palestrina).

The measures taken to prevent Bruno continuing to speak have resulted in his becoming a symbol for free thought and speech in present-day Rome, where an annual memorial service takes place close to the spot where he was executed.

Physical appearance

The earliest likeness of Bruno is an engraving published in 1715 and cited by Salvestrini as "the only known portrait of Bruno". Salvestrini suggests that it is a re-engraving made from a now lost original. This engraving has provided the source for later images.

The records of Bruno's imprisonment by the Venetian inquisition in May 1592 describe him as a man "of average height, with a hazel-coloured beard and the appearance of being about forty years of age". Alternately, a passage in a work by George Abbot indicates that Bruno was of diminutive stature: "When that Italian Didapper, who intituled himselfe Philotheus Iordanus Brunus Nolanus, magis elaboratae Theologiae Doctor, &c. with a name longer than his body...". The word "didapper" used by Abbot is the derisive term which at the time meant "a small diving waterfowl".

Cosmology

Contemporary cosmological beliefs

In the first half of the 15th century, Nicholas of Cusa challenged the then widely accepted philosophies of Aristotelianism, envisioning instead an infinite universe whose center was everywhere and circumference nowhere, and moreover teeming with countless stars. He also predicted that neither were the rotational orbits circular nor were their movements uniform.

In the second half of the 16th century, the theories of Copernicus (1473–1543) began diffusing through Europe. Copernicus conserved the idea of planets fixed to solid spheres, but considered the apparent motion of the stars to be an illusion caused by the rotation of the Earth on its axis; he also preserved the notion of an immobile center, but it was the Sun rather than the Earth. Copernicus also argued the Earth was a planet orbiting the Sun once every year. However he maintained the Ptolemaic hypothesis that the orbits of the planets were composed of perfect circles—deferents and epicycles—and that the stars were fixed on a stationary outer sphere.

Despite the widespread publication of Copernicus' work De revolutionibus orbium coelestium, during Bruno's time most educated Catholics subscribed to the Aristotelian geocentric view that the Earth was the center of the universe, and that all heavenly bodies revolved around it. The ultimate limit of the universe was the primum mobile, whose diurnal rotation was conferred upon it by a transcendental God, not part of the universe (although, as the kingdom of heaven, adjacent to it), a motionless prime mover and first cause. The fixed stars were part of this celestial sphere, all at the same fixed distance from the immobile Earth at the center of the sphere. Ptolemy had numbered these at 1,022, grouped into 48 constellations. The planets were each fixed to a transparent sphere.

Few astronomers of Bruno's time accepted Copernicus's heliocentric model. Among those who did were the Germans Michael Maestlin (1550–1631), Christoph Rothmann, Johannes Kepler (1571–1630); the Englishman Thomas Digges (c. 1546–1595), author of A Perfit Description of the Caelestial Orbes; and the Italian Galileo Galilei (1564–1642).

Bruno's cosmological claims

In 1584, Bruno published two important philosophical dialogues (La Cena de le Ceneri and De l'infinito universo et mondi) in which he argued against the planetary spheres (Christoph Rothmann did the same in 1586 as did Tycho Brahe in 1587) and affirmed the Copernican principle.

In particular, to support the Copernican view and oppose the objection according to which the motion of the Earth would be perceived by means of the motion of winds, clouds etc., in La Cena de le Ceneri Bruno anticipates some of the arguments of Galilei on the relativity principle. Note that he also uses the example now known as Galileo's ship.

Theophilus – [...] air through which the clouds and winds move are parts of the Earth, [...] to mean under the name of Earth the whole machinery and the entire animated part, which consists of dissimilar parts; so that the rivers, the rocks, the seas, the whole vaporous and turbulent air, which is enclosed within the highest mountains, should belong to the Earth as its members, just as the air [does] in the lungs and in other cavities of animals by which they breathe, widen their arteries, and other similar effects necessary for life are performed. The clouds, too, move through accidents in the body of the Earth and are in its bowels as are the waters. [...] With the Earth move [...] all things that are on the Earth. If, therefore, from a point outside the Earth something were thrown upon the Earth, it would lose, because of the latter's motion, its straightness as would be seen on the ship [...] moving along a river, if someone on point C of the riverbank were to throw a stone along a straight line, and would see the stone miss its target by the amount of the velocity of the ship's motion. But if someone were placed high on the mast of that ship, move as it may however fast, he would not miss his target at all, so that the stone or some other heavy thing thrown downward would not come along a straight line from the point E which is at the top of the mast, or cage, to the point D which is at the bottom of the mast, or at some point in the bowels and body of the ship. Thus, if from the point D to the point E someone who is inside the ship would throw a stone straight up, it would return to the bottom along the same line however far the ship moved, provided it was not subject to any pitch and roll."

Bruno's infinite universe was filled with a substance—a "pure air", aether, or spiritus—that offered no resistance to the heavenly bodies which, in Bruno's view, rather than being fixed, moved under their own impetus (momentum). Most dramatically, he completely abandoned the idea of a hierarchical universe.

The universe is then one, infinite, immobile.... It is not capable of comprehension and therefore is endless and limitless, and to that extent infinite and indeterminable, and consequently immobile.

Bruno's cosmology distinguishes between "suns" which produce their own light and heat, and have other bodies moving around them; and "earths" which move around suns and receive light and heat from them. Bruno suggested that some, if not all, of the objects classically known as fixed stars are in fact suns. According to astrophysicist Steven Soter, he was the first person to grasp that "stars are other suns with their own planets."

Bruno wrote that other worlds "have no less virtue nor a nature different from that of our Earth" and, like Earth, "contain animals and inhabitants".

During the late 16th century, and throughout the 17th century, Bruno's ideas were held up for ridicule, debate, or inspiration. Margaret Cavendish, for example, wrote an entire series of poems against "atoms" and "infinite worlds" in Poems and Fancies in 1664. Bruno's true, if partial, vindication would have to wait for the implications and impact of Newtonian cosmology.

Bruno's overall contribution to the birth of modern science is still controversial. Some scholars follow Frances Yates in stressing the importance of Bruno's ideas about the universe being infinite and lacking geocentric structure as a crucial crossing point between the old and the new. Others see in Bruno's idea of multiple worlds instantiating the infinite possibilities of a pristine, indivisible One, a forerunner of Everett's many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics.

While many academics note Bruno's theological position as pantheism, several have described it as pandeism, and some also as panentheism. Physicist and philosopher Max Bernhard Weinstein in his Welt- und Lebensanschauungen, Hervorgegangen aus Religion, Philosophie und Naturerkenntnis ("World and Life Views, Emerging From Religion, Philosophy and Nature"), wrote that the theological model of pandeism was strongly expressed in the teachings of Bruno, especially with respect to the vision of a deity for which "the concept of God is not separated from that of the universe." However, Otto Kern takes exception to what he considers Weinstein's overbroad assertions that Bruno, as well as other historical philosophers such as John Scotus Eriugena, Anselm of Canterbury, Nicholas of Cusa, Mendelssohn, and Lessing, were pandeists or leaned towards pandeism. Discover editor Corey S. Powell also described Bruno's cosmology as pandeistic, writing that it was "a tool for advancing an animist or Pandeist theology", and this assessment of Bruno as a pandeist was agreed with by science writer Michael Newton Keas, and The Daily Beast writer David Sessions.

Retrospective views of Bruno

Late Vatican position

The Vatican has published few official statements about Bruno's trial and execution. In 1942, Cardinal Giovanni Mercati, who discovered a number of lost documents relating to Bruno's trial, stated that the Church was perfectly justified in condemning him. On the 400th anniversary of Bruno's death, in 2000, Cardinal Angelo Sodano declared Bruno's death to be a "sad episode" but, despite his regret, he defended Bruno's prosecutors, maintaining that the Inquisitors "had the desire to serve freedom and promote the common good and did everything possible to save his life". In the same year, Pope John Paul II made a general apology for "the use of violence that some have committed in the service of truth".

A martyr of science

Some authors have characterized Bruno as a "martyr of science", suggesting parallels with the Galileo affair which began around 1610. "It should not be supposed," writes A. M. Paterson of Bruno and his "heliocentric solar system", that he "reached his conclusions via some mystical revelation....His work is an essential part of the scientific and philosophical developments that he initiated." Paterson echoes Hegel in writing that Bruno "ushers in a modern theory of knowledge that understands all natural things in the universe to be known by the human mind through the mind's dialectical structure".

Ingegno writes that Bruno embraced the philosophy of Lucretius, "aimed at liberating man from the fear of death and the gods." Characters in Bruno's Cause, Principle and Unity desire "to improve speculative science and knowledge of natural things," and to achieve a philosophy "which brings about the perfection of the human intellect most easily and eminently, and most closely corresponds to the truth of nature."

Other scholars oppose such views, and claim Bruno's martyrdom to science to be exaggerated, or outright false. For Yates, while "nineteenth century liberals" were thrown "into ecstasies" over Bruno's Copernicanism, "Bruno pushes Copernicus' scientific work back into a prescientific stage, back into Hermeticism, interpreting the Copernican diagram as a hieroglyph of divine mysteries."

According to historian Mordechai Feingold, "Both admirers and critics of Giordano Bruno basically agree that he was pompous and arrogant, highly valuing his opinions and showing little patience with anyone who even mildly disagreed with him." Discussing Bruno's experience of rejection when he visited Oxford University, Feingold suggests that "it might have been Bruno's manner, his language and his self-assertiveness, rather than his ideas" that caused offence.

Theological heresy

In his Lectures on the History of Philosophy, Hegel writes that Bruno's life represented "a bold rejection of all Catholic beliefs resting on mere authority."

Alfonso Ingegno states that Bruno's philosophy "challenges the developments of the Reformation, calls into question the truth-value of the whole of Christianity, and claims that Christ perpetrated a deceit on mankind... Bruno suggests that we can now recognize the universal law which controls the perpetual becoming of all things in an infinite universe." A. M. Paterson says that, while we no longer have a copy of the official papal condemnation of Bruno, his heresies included "the doctrine of the infinite universe and the innumerable worlds" and his beliefs "on the movement of the earth".

Michael White notes that the Inquisition may have pursued Bruno early in his life on the basis of his opposition to Aristotle, interest in Arianism, reading of Erasmus, and possession of banned texts. White considers that Bruno's later heresy was "multifaceted" and may have rested on his conception of infinite worlds. "This was perhaps the most dangerous notion of all... If other worlds existed with intelligent beings living there, did they too have their visitations? The idea was quite unthinkable."

Frances Yates rejects what she describes as the "legend that Bruno was prosecuted as a philosophical thinker, was burned for his daring views on innumerable worlds or on the movement of the earth." Yates however writes that "the Church was... perfectly within its rights if it included philosophical points in its condemnation of Bruno's heresies" because "the philosophical points were quite inseparable from the heresies."

According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, "in 1600 there was no official Catholic position on the Copernican system, and it was certainly not a heresy. When [...] Bruno [...] was burned at the stake as a heretic, it had nothing to do with his writings in support of Copernican cosmology."

The website of the Vatican Apostolic Archive, discussing a summary of legal proceedings against Bruno in Rome, states:

"In the same rooms where Giordano Bruno was questioned, for the same important reasons of the relationship between science and faith, at the dawning of the new astronomy and at the decline of Aristotle's philosophy, sixteen years later, Cardinal Bellarmino, who then contested Bruno's heretical theses, summoned Galileo Galilei, who also faced a famous inquisitorial trial, which, luckily for him, ended with a simple abjuration."