From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In physical chemistry, the van der Waals forces (or van der Waals' interaction), named after Dutch scientist Johannes Diderik van der Waals, is the sum of the attractive or repulsive forces between molecules (or between parts of the same molecule) other than those due to covalent bonds, or the electrostatic interaction of ions with one another, with neutral molecules, or with charged molecules.[1] The resulting van der Waals forces can be attractive or repulsive.[2]

The term includes:

- force between two permanent dipoles (Keesom force)

- force between a permanent dipole and a corresponding induced dipole (Debye force)

- force between two instantaneously induced dipoles (London dispersion force).

In low molecular weight alcohols, the hydrogen-bonding properties of the polar hydroxyl group dominate other weaker van der Waals interactions. In higher molecular weight alcohols, the properties of the nonpolar hydrocarbon chain(s) dominate and define the solubility. Van der Waals forces quickly vanish at longer distances between interacting molecules.

In 2012, the first direct measurements of the strength of the van der Waals force for a single organic molecule bound to a metal surface was made via atomic force microscopy and corroborated with density functional calculations.[3]

Definition

Van der Waals forces include attractions and repulsions between atoms, molecules, and surfaces, as well as other intermolecular forces. They differ from covalent and ionic bonding in that they are caused by correlations in the fluctuating polarizations of nearby particles (a consequence of quantum dynamics[4]).

Intermolecular forces have four major contributions:

- A repulsive component resulting from the Pauli exclusion principle that prevents the collapse of molecules.

- Attractive or repulsive electrostatic interactions between permanent charges (in the case of molecular ions), dipoles (in the case of molecules without inversion center), quadrupoles (all molecules with symmetry lower than cubic), and in general between permanent multipoles. The electrostatic interaction is sometimes called the Keesom interaction or Keesom force after Willem Hendrik Keesom.

- Induction (also known as polarization), which is the attractive interaction between a permanent multipole on one molecule with an induced multipole on another. This interaction is sometimes called Debye force after Peter J.W. Debye.

- Dispersion (usually named after Fritz London), which is the attractive interaction between any pair of molecules, including non-polar atoms, arising from the interactions of instantaneous multipoles.

All intermolecular/van der Waals forces are anisotropic (except those between two noble gas atoms), which means that they depend on the relative orientation of the molecules. The induction and dispersion interactions are always attractive, irrespective of orientation, but the electrostatic interaction changes sign upon rotation of the molecules. That is, the electrostatic force can be attractive or repulsive, depending on the mutual orientation of the molecules. When molecules are in thermal motion, as they are in the gas and liquid phase, the electrostatic force is averaged out to a large extent, because the molecules thermally rotate and thus probe both repulsive and attractive parts of the electrostatic force. Sometimes this effect is expressed by the statement that "random thermal motion around room temperature can usually overcome or disrupt them" (which refers to the electrostatic component of the van der Waals force). Clearly, the thermal averaging effect is much less pronounced for the attractive induction and dispersion forces.

The Lennard-Jones potential is often used as an approximate model for the isotropic part of a total (repulsion plus attraction) van der Waals force as a function of distance.

Van der Waals forces are responsible for certain cases of pressure broadening (van der Waals broadening) of spectral lines and the formation of van der Waals molecules. The London-van der Waals forces are related to the Casimir effect for dielectric media, the former being the microscopic description of the latter bulk property. The first detailed calculations of this were done in 1955 by E. M. Lifshitz.[5] A more general theory of van der Waals forces has also been developed.[6][7]

The main characteristics of van der Waals forces are:- [8]

- They are weaker than normal covalent ionic bonds.

- Van der Waals forces are additive and cannot be saturated.

- They have no directional characteristic.

- They are all short-range forces and hence only interactions between nearest need to be considered instead of all the particles. The greater is the attraction if the molecules are closer due to Van der Waals forces.

- Van der Waals forces are independent of temperature except dipole - dipole interactions.

London dispersion force

London dispersion forces, named after the German-American physicist Fritz London, are weak intermolecular forces that arise from the interactive forces between instantaneous multipoles in molecules without permanent multipole moments. These forces dominate the interaction of non-polar molecules, and are often more significant than Keesom and Debye forces in polar molecules. London dispersion forces are also known as dispersion forces, London forces, or instantaneous dipole–induced dipole forces. The strength of London dispersion forces is proportional to the polarizability of the molecule, which in turn depends on the total number of electrons and the area over which they are spread. Any connection between the strength of London dispersion forces and mass is coincidental.Van der Waals forces between macroscopic objects

For macroscopic bodies with known volumes and numbers of atoms or molecules per unit volume, the total van der Waals force is often computed based on the "microscopic theory" as the sum over all interacting pairs. It is necessary to integrate over the total volume of the object, which makes the calculation dependent on the objects' shapes. For example, the van der Waals' interaction energy between spherical bodies of radii R1 and R2 and with smooth surfaces was approximated in 1937 by Hamaker[9] (using London's famous 1937 equation for the dispersion interaction energy between atoms/molecules[10] as the starting point) by:![\begin{align}

&U(z;R_{1},R_{2}) = -\frac{A}{6}\left(\frac{2R_{1}R_{2}}{z^2 - (R_{1} + R_{2})^2} + \frac{2R_{1}R_{2}}{z^2 - (R_{1} - R_{2})^2} + \ln\left[\frac{z^2-(R_{1}+ R_{2})^2}{z^2-(R_{1}- R_{2})^2}\right]\right)

\end{align}](//upload.wikimedia.org/math/5/7/4/574d97354e30c09385b05957e1348e12.png) (1)

(1)

.

.In the limit of close-approach, the spheres are sufficiently large compared to the distance between them; i.e.,

, so that equation (1) for the potential energy function simplifies to:

, so that equation (1) for the potential energy function simplifies to: (2)

(2)

. This yields:

. This yields: (3)

(3)

From the expression above, it is seen that the van der Waals force decreases with decreasing size of bodies (R). Nevertheless, the strength of inertial forces, such as gravity and drag/lift, decrease to a greater extent. Consequently, the van der Waals forces become dominant for collections of very small particles such as very fine-grained dry powders (where there are no capillary forces present) even though the force of attraction is smaller in magnitude than it is for larger particles of the same substance. Such powders are said to be cohesive, meaning they are not as easily fluidized or pneumatically conveyed as easily as their more coarse-grained counterparts. Generally, free-flow occurs with particles greater than about 250 μm.

The van der Waals force of adhesion is also dependent on the surface topography. If there are surface asperities, or protuberances, that result in a greater total area of contact between two particles or between a particle and a wall, this increases the van der Waals force of attraction as well as the tendency for mechanical interlocking.

The microscopic theory assumes pairwise additivity. It neglects many-body interactions and retardation. A more rigorous approach accounting for these effects, called the "macroscopic theory" was developed by Lifshitz in 1956.[14] Langbein derived a much more cumbersome "exact" expression in 1970 for spherical bodies within the framework of the Lifshitz theory[15] while a simpler macroscopic model approximation had been made by Derjaguin as early as 1934.[16] Expressions for the van der Waals forces for many different geometries using the Lifshitz theory have likewise been published.

Use by geckos and spiders

The ability of geckos – which can hang on a glass surface using only one toe – to climb on sheer surfaces has been attributed to the van der Waals forces between these surfaces and the spatulae, or microscopic projections, which cover the hair-like setae found on their footpads.[17][18] A later study suggested that capillary adhesion might play a role,[19] but that hypothesis has been rejected by more recent studies.[20][21][22] There were efforts in 2008 to create a dry glue that exploits the effect,[23] and success was achieved in 2011 to create an adhesive tape on similar grounds.[24] In 2011, a paper was published relating the effect to both velcro-like hairs and the presence of lipids in gecko footprints.[25]

Some spiders have convergently evolved similar setae on their scopulae or scopula pads, enabling them to climb or hang upside-down from extremely smooth surfaces such as glass or porcelain.[26]

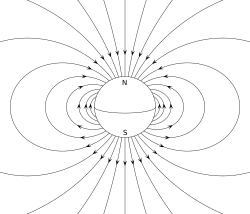

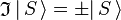

is the center of mass of the molecule/group of particles.

is the center of mass of the molecule/group of particles.

is the dipole operator and

is the dipole operator and  is the inversion operator. The permanent dipole moment of an atom in a non-degenerate state (see

is the inversion operator. The permanent dipole moment of an atom in a non-degenerate state (see

is an S-state, non-degenerate, wavefunction, which is symmetric or antisymmetric under inversion:

is an S-state, non-degenerate, wavefunction, which is symmetric or antisymmetric under inversion:  . Since the product of the wavefunction (in the ket) and its complex conjugate (in the bra) is always symmetric under inversion and its inverse,

. Since the product of the wavefunction (in the ket) and its complex conjugate (in the bra) is always symmetric under inversion and its inverse,

, being a symmetry operator, is

, being a symmetry operator, is  and

and  may be moved from bra to ket and then becomes

may be moved from bra to ket and then becomes  . Since the only quantity that is equal to minus itself is the zero, the expectation value vanishes,

. Since the only quantity that is equal to minus itself is the zero, the expectation value vanishes,

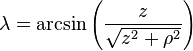

is the unit vector parallel to r;

is the unit vector parallel to r;

is a unit vector in the direction of r, p is the (vector)

is a unit vector in the direction of r, p is the (vector)

.

. .

.

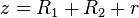

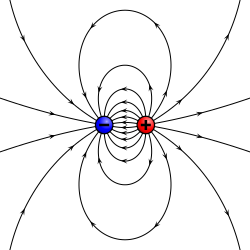

along the

along the  direction of the form

direction of the form

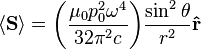

, the far-field takes the simpler form of a radiating "spherical" wave, but with angular dependence embedded in the cross-product:

, the far-field takes the simpler form of a radiating "spherical" wave, but with angular dependence embedded in the cross-product:

) responsible for such "donut-shaped" angular distribution is precisely the

) responsible for such "donut-shaped" angular distribution is precisely the  "p" wave.

"p" wave.