From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The

American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution which occurred in

colonial North America between 1765 and 1783. The American Patriots in the

Thirteen Colonies defeated the British in the

American Revolutionary War (1775–1783) with the assistance of France, winning independence from Great Britain and establishing the

United States of America.

The

American colonials proclaimed "

no taxation without representation" starting with the

Stamp Act Congress

in 1765. They had no representatives in the British Parliament and so

rejected Parliament's authority to tax them. Protests steadily escalated

to the

Boston Massacre in 1770 and the

burning of the Gaspee in

Rhode Island in 1772, followed by the

Boston Tea Party in December 1773. The British responded by closing

Boston Harbor and enacting a

series of punitive laws which effectively rescinded

Massachusetts Bay Colony's

rights of self-government. The other colonies rallied behind

Massachusetts, and a group of American Patriot leaders set up their own

government in late 1774 at the

Continental Congress to coordinate their resistance of Britain; other colonists retained their allegiance to the Crown and were known as

Loyalists or

Tories.

Tensions erupted into battle between Patriot militia and British regulars when

King George's forces attempted to destroy American military supplies at

Lexington and Concord

on April 19, 1775. The conflict quickly escalated into war, during

which the Patriots (and later their French allies) fought the British

and Loyalists in the Revolutionary War. Each colony formed a

Provincial Congress which assumed power from the former colonial governments, suppressed Loyalism, and recruited a

Continental Army led by General

George Washington. The Continental Congress declared King George a tyrant who trampled the colonists'

rights as Englishmen, and they declared the colonies

free and independent states on July 2, 1776. The Patriot leadership professed the political philosophies of

liberalism and

republicanism to reject monarchy and aristocracy, and they proclaimed that all men are created equal.

The Patriots unsuccessfully

attempted to invade Quebec during the winter of 1775–76, expecting like-minded colonists in British Canada to rally to the cause. The newly created Continental Army

forced the British military out of Boston in March 1776, but

the British captured New York City

and its strategic harbor that summer, which they held for the duration

of the war. The Royal Navy blockaded ports and captured other cities for

brief periods, but they failed to destroy Washington's forces. The

Continental Army captured a British army at the

Battle of Saratoga

in October 1777, and France then entered the war as an ally of the

United States. Britain then refocused its war to make France the main

enemy. Britain also attempted to hold the Southern states with the

anticipated aid of Loyalists, and the war moved south.

Charles Cornwallis captured an army at

Charleston, South Carolina

in early 1780, but he failed to enlist enough volunteers from Loyalist

civilians to take effective control of the territory. Finally, a

combined American and French force captured a second British army

at Yorktown in the fall of 1781, effectively ending the war. The

Treaty of Paris

was signed September 3, 1783, formally ending the conflict and

confirming the new nation's complete separation from the British Empire.

The United States took possession of nearly all the territory east of

the Mississippi River and south of the Great Lakes, with the British

retaining control of Canada, and Spain taking Florida.

Among the significant results of the Revolution were American

independence and friendly economic trade with Britain. The Americans

adopted the

United States Constitution, establishing a strong national government which included an elected

executive, a

national judiciary, and an elected bicameral

Congress representing states in the

Senate and the population in the

House of Representatives. Around 60,000 Loyalists migrated to other British territories, particularly to

British North America (Canada), but the great majority remained in the United States.

Origin

1651–1748: Early seeds

As early as 1651, the English government had sought to regulate trade in the

American colonies, and Parliament passed the

Navigation Acts on October 9 to provide the plantation colonies of the south with a profitable export market. The Acts prohibited British producers from growing tobacco and also encouraged shipbuilding, particularly in the

New England colonies. Some argue that the economic impact was minimal on the colonists,

but the political friction which the acts triggered was more serious,

as the merchants most directly affected were also the most politically

active.

King Philip's War

ended in 1678, which the New England colonies fought without any

military assistance from England, and this contributed to the

development of a unique identity separate from that of the British

people. But

King Charles II

determined to bring the New England colonies under a more centralized

administration in the 1680s to regulate trade to more effectively

benefit the homeland. The New England colonists fiercely opposed his efforts, and the Crown nullified their colonial charters in response. Charles' successor

James II finalized these efforts in 1686, establishing the consolidated

Dominion of New England.

Dominion rule triggered bitter resentment throughout New England; the

enforcement of the unpopular Navigation Acts and the curtailing of local

democracy angered the colonists. New Englanders were encouraged, however, by a

change of government in England which saw James II effectively abdicate, and a

populist uprising in New England overthrew Dominion rule on April 18, 1689.

Colonial governments reasserted their control after the revolt, and

successive governments made no more attempts to restore the Dominion.

Subsequent English governments continued in their efforts to tax certain goods, passing acts regulating the trade of

wool,

hats, and

molasses.

The Molasses Act of 1733 was particularly egregious to the colonists,

as a significant part of colonial trade relied on molasses. The taxes

severely damaged the New England economy and resulted in a surge of

smuggling, bribery, and intimidation of customs officials. Colonial wars fought in America were also a source of considerable tension. The British captured the fortress of

Louisbourg during

King George's War

but then ceded it back to France in 1748. New England colonists

resented their losses of lives, as well as the effort and expenditure

involved in subduing the fortress, only to have it returned to their

erstwhile enemy.

It may be said as truly that the

American Revolution was an aftermath of the Anglo-French conflict in the

New World carried on between 1754 and 1763.

The

Royal Proclamation of 1763 redrew boundaries of the lands west of Quebec and west of a line running along the crest of the

Allegheny Mountains,

making them Indian territory and barred to colonial settlement for two

years. The colonists protested, and the boundary line was adjusted in a

series of treaties with

Indian tribes. In 1768, the

Iroquois agreed to the

Treaty of Fort Stanwix, and the

Cherokee agreed to the

Treaty of Hard Labour followed in 1770 by the

Treaty of Lochaber.

The treaties opened most of Kentucky and West Virginia to colonial

settlement. The new map was drawn up at the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in

1768 which moved the line much farther to the west, from the green line

to the red line on the map at right.

1764–1766: Taxes imposed and withdrawn

Notice of Stamp Act of 1765 in newspaper

Prime Minister

George Grenville

asserted in 1762 that the whole revenue of the custom houses in America

amounted to one or two thousand pounds a year, and that the English

exchequer was paying between seven and eight thousand pounds a year to

collect. Adam Smith wrote in

The Wealth of Nations

that Parliament "has never hitherto demanded of [the American colonies]

anything which even approached to a just proportion to what was paid by

their fellow subjects at home."

As early as 1651, the English government had sought to regulate

trade in the American colonies. On October 9, 1651, they passed the

Navigation Acts to pursue a

mercantilist policy intended to ensure that trade enriched Great Britain but prohibited trade with any other nations. Parliament also passed the

Sugar Act,

decreasing the existing customs duties on sugar and molasses but

providing stricter measures of enforcement and collection. That same

year, Grenville proposed direct taxes on the colonies to raise revenue,

but he delayed action to see whether the colonies would propose some way

to raise the revenue themselves.

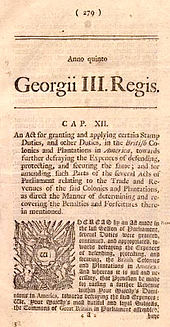

Parliament finally passed the

Stamp Act

in March 1765, which imposed direct taxes on the colonies for the first

time. All official documents, newspapers, almanacs, and pamphlets were

required to have the stamps—even decks of playing cards. The colonists

did not object that the taxes were high; they were actually low.

They objected to their lack of representation in the Parliament, which

gave them no voice concerning legislation that affected them.

Benjamin Franklin

testified in Parliament in 1766 that Americans already contributed

heavily to the defense of the Empire. He said that local governments had

raised, outfitted, and paid 25,000 soldiers to fight France—as many as

Britain itself sent—and spent many millions from American treasuries

doing so in the

French and Indian War alone.

London had to deal with 1,500 politically well-connected British Army

soldiers. The decision was to keep them on active duty with full pay,

but they had to be stationed somewhere. Stationing a standing army in

Great Britain during peacetime was politically unacceptable, so the

decision was made to station them in America and have the Americans pay

them. The soldiers had no military mission; they were not there to

defend the colonies because there was no threat to the colonies.

The

Sons of Liberty

formed that same year in 1765, and they used public demonstrations,

boycotts, and threats of violence to ensure that the British tax laws

were unenforceable. In Boston, the Sons of Liberty burned the records of

the vice admiralty court and looted the home of chief justice

Thomas Hutchinson. Several legislatures called for united action, and nine colonies sent delegates to the

Stamp Act Congress in New York City in October. Moderates led by

John Dickinson drew up a "

Declaration of Rights and Grievances" stating that taxes passed without representation violated their

rights as Englishmen, and colonists emphasized their determination by boycotting imports of British merchandise.

The Parliament at Westminster saw itself as the supreme lawmaking

authority throughout all British possessions and thus entitled to levy

any tax without colonial approval.

They argued that the colonies were legally British corporations

subordinate to the British parliament, and they pointed to numerous

instances where Parliament had made laws in the past that were binding

on the colonies. Parliament insisted that the colonies effectively enjoyed a "

virtual representation" as most British people did, as only a small minority of the British population elected representatives to Parliament, but Americans such as

James Otis maintained that they were not "virtually represented" at all.

The

Rockingham

government came to power in July 1765, and Parliament debated whether

to repeal the stamp tax or to send an army to enforce it. Benjamin

Franklin made the case for repeal, explaining that the colonies had

spent heavily in manpower, money, and blood defending the empire in a

series of wars against the French and Indians, and that further taxes to

pay for those wars were unjust and might bring about a rebellion.

Parliament agreed and repealed the tax on February 21, 1766, but they

insisted in the

Declaratory Act of March 1766 that they retained full power to make laws for the colonies "in all cases whatsoever". The repeal nonetheless caused widespread celebrations in the colonies.

1767–1773: Townshend Acts and the Tea Act

In 1767, the Parliament passed the

Townshend Acts

which placed duties on a number of staple goods, including paper,

glass, and tea, and established a Board of Customs in Boston to more

rigorously execute trade regulations. The new taxes were enacted on the

belief that Americans only objected to internal taxes and not to

external taxes such as custom duties. The Americans, however, argued

against the constitutionality of the act because its purpose was to

raise revenue and not regulate trade.

Colonists responded by organizing new boycotts of British goods. These

boycotts were less effective, however, as the Townshend goods were

widely used.

In February 1768, the Assembly of Massachusetts Bay

issued a circular letter

to the other colonies urging them to coordinate resistance. The

governor dissolved the assembly when it refused to rescind the letter.

Meanwhile, a riot broke out in Boston in June 1768 over the seizure of

the sloop

Liberty, owned by

John Hancock,

for alleged smuggling. Customs officials were forced to flee, prompting

the British to deploy troops to Boston. A Boston town meeting declared

that no obedience was due to parliamentary laws and called for the

convening of a convention. A convention assembled but only issued a mild

protest before dissolving itself. In January 1769, Parliament responded

to the unrest by reactivating the

Treason Act 1543

which called for subjects outside the realm to face trials for treason

in England. The governor of Massachusetts was instructed to collect

evidence of said treason, and the threat caused widespread outrage,

though it was not carried out.

On March 5, 1770, a large crowd gathered around a group of

British soldiers. The crowd grew threatening, throwing snowballs, rocks,

and debris at them. One soldier was clubbed and fell.

There was no order to fire, but the soldiers fired into the crowd

anyway. They hit 11 people; three civilians died at the scene of the

shooting, and two died after the incident. The event quickly came to be

called the

Boston Massacre. The soldiers were tried and acquitted (defended by

John Adams),

but the widespread descriptions soon began to turn colonial sentiment

against the British. This began a downward spiral in the relationship

between Britain and the Province of Massachusetts.

A new ministry under

Lord North

came to power in 1770, and Parliament withdrew all taxes except the tax

on tea, giving up its efforts to raise revenue while maintaining the

right to tax. This temporarily resolved the crisis, and the boycott of

British goods largely ceased, with only the more radical patriots such

as

Samuel Adams continuing to agitate.

In June 1772, American

patriots, including

John Brown, burned a British warship that had been vigorously enforcing unpopular trade regulations in what became known as the

Gaspee Affair. The affair was investigated for possible treason, but no action was taken.

In 1772, it became known that the Crown intended to pay fixed

salaries to the governors and judges in Massachusetts, which had been

paid by local authorities. This would reduce the influence of colonial

representatives over their government. Samuel Adams in Boston set about

creating new Committees of Correspondence, which linked Patriots in all

13 colonies and eventually provided the framework for a rebel

government. Virginia, the largest colony, set up its Committee of

Correspondence in early 1773, on which Patrick Henry and Thomas

Jefferson served.

A total of about 7,000 to 8,000 Patriots served on "Committees of

Correspondence" at the colonial and local levels, comprising most of

the leadership in their communities. Loyalists were excluded. The

committees became the

leaders

of the American resistance to British actions, and largely determined

the war effort at the state and local level. When the First Continental

Congress decided to boycott British products, the colonial and local

Committees took charge, examining merchant records and publishing the

names of merchants who attempted to defy the boycott by importing

British goods.

In 1773,

private letters were published

in which Massachusetts Governor Thomas Hutchinson claimed that the

colonists could not enjoy all English liberties, and Lieutenant Governor

Andrew Oliver

called for the direct payment of colonial officials. The letters'

contents were used as evidence of a systematic plot against American

rights, and discredited Hutchinson in the eyes of the people; the

Assembly petitioned for his recall.

Benjamin Franklin,

postmaster general for the colonies, acknowledged that he leaked the

letters, which led to him being berated by British officials and fired

from his job.

Meanwhile, Parliament passed the

Tea Act to lower the price of taxed tea exported to the colonies to help the

East India Company

undersell smuggled Dutch tea. Special consignees were appointed to sell

the tea to bypass colonial merchants. The act was opposed by those who

resisted the taxes and also by smugglers who stood to lose business.

In most instances, the consignees were forced to resign and the tea was

turned back, but Massachusetts governor Hutchinson refused to allow

Boston merchants to give in to pressure. A town meeting in Boston

determined that the tea would not be landed, and ignored a demand from

the governor to disperse. On December 16, 1773, a group of men, led by

Samuel Adams and dressed to evoke the appearance of American Indians,

boarded the ships of the

British East India Company

and dumped £10,000 worth of tea from their holds (approximately

£636,000 in 2008) into Boston Harbor. Decades later, this event became

known as the

Boston Tea Party and remains a significant part of American patriotic lore.

1774–1775: Intolerable Acts and the Quebec Act

The British government responded by passing several Acts which came to be known as the

Intolerable Acts, which further darkened colonial opinion towards the British. They consisted of four laws enacted by the British parliament. The first was the

Massachusetts Government Act which altered the Massachusetts charter and restricted town meetings. The second act was the

Administration of Justice Act

which ordered that all British soldiers to be tried were to be

arraigned in Britain, not in the colonies. The third Act was the

Boston Port Act,

which closed the port of Boston until the British had been compensated

for the tea lost in the Boston Tea Party. The fourth Act was the

Quartering Act of 1774, which allowed royal governors to house British troops in the homes of citizens without requiring permission of the owner.

In response, Massachusetts patriots issued the

Suffolk Resolves

and formed an alternative shadow government known as the "Provincial

Congress" which began training militia outside British-occupied Boston. In September 1774, the

First Continental Congress

convened, consisting of representatives from each colony, to serve as a

vehicle for deliberation and collective action. During secret debates,

conservative

Joseph Galloway

proposed the creation of a colonial Parliament that would be able to

approve or disapprove of acts of the British Parliament, but his idea

was not accepted. The Congress instead endorsed the proposal of John

Adams that Americans would obey Parliament voluntarily but would resist

all taxes in disguise. Congress called for a boycott beginning on 1

December 1774 of all British goods; it was enforced by new committees

authorized by the Congress.

Military hostilities begin

Join, or Die by Benjamin Franklin was recycled to encourage the former colonies to unite against British rule.

Massachusetts was declared in a state of rebellion in February 1775

and the British garrison received orders to disarm the rebels and arrest

their leaders, leading to the

Battles of Lexington and Concord

on 19 April 1775. The Patriots laid siege to Boston, expelled royal

officials from all the colonies, and took control through the

establishment of

Provincial Congresses. The

Battle of Bunker Hill

followed on June 17, 1775. It was a British victory—but at a great

cost: about 1,000 British casualties from a garrison of about 6,000, as

compared to 500 American casualties from a much larger force. The Second Continental Congress was divided on the best course of action, but eventually produced the

Olive Branch Petition, in which they attempted to come to an accord with

King George. The king, however, issued a

Proclamation of Rebellion which stated that the states were "in rebellion" and the members of Congress were traitors.

The war that arose was in some ways a classic

insurgency As

Benjamin Franklin wrote to

Joseph Priestley

in October 1775: "Britain, at the expense of three millions, has killed

150 Yankees this campaign, which is £20,000 a head ... During the same

time, 60,000 children have been born in America. From these data his

mathematical head will easily calculate the time and expense necessary

to kill us all.".

In the winter of 1775, the Americans

invaded Canada under generals

Benedict Arnold and

Richard Montgomery,

expecting to rally sympathetic colonists there. The attack was a

failure; many Americans who weren't killed were either captured or died

of smallpox.

In March 1776, the Continental Army forced the British to

evacuate Boston,

with George Washington as the commander of the new army. The

revolutionaries now fully controlled all thirteen colonies and were

ready to declare independence. There still were many Loyalists, but they

were no longer in control anywhere by July 1776, and all of the Royal

officials had fled.

Creating new state constitutions

Following the

Battle of Bunker Hill

in June 1775, the Patriots had control of Massachusetts outside the

Boston city limits, and the Loyalists suddenly found themselves on the

defensive with no protection from the British army. In all 13 colonies,

Patriots had overthrown their existing governments, closing courts and

driving away British officials. They had elected conventions and

"legislatures" that existed outside any legal framework; new

constitutions were drawn up in each state to supersede royal charters.

They declared that they were states, not colonies.

On January 5, 1776,

New Hampshire

ratified the first state constitution. In May 1776, Congress voted to

suppress all forms of crown authority, to be replaced by locally created

authority. Virginia,

South Carolina, and New Jersey created their constitutions before July 4.

Rhode Island and

Connecticut simply took their existing

royal charters and deleted all references to the crown.

The new states were all committed to republicanism, with no inherited

offices. They decided what form of government to create, and also how to

select those who would craft the constitutions and how the resulting

document would be ratified. On 26 May 1776,

John Adams wrote James Sullivan from Philadelphia:

Depend upon it, sir, it is

dangerous to open so fruitful a source of controversy and altercation,

as would be opened by attempting to alter the qualifications of voters.

There will be no end of it. New claims will arise. Women will demand a

vote. Lads from twelve to twenty one will think their rights not enough

attended to, and every man, who has not a farthing, will demand an equal

voice with any other in all acts of state. It tends to confound and

destroy all distinctions, and prostrate all ranks, to one common

level[.]

- Property qualifications for voting and even more substantial

requirements for elected positions (though New York and Maryland lowered

property qualifications)

- Bicameral legislatures, with the upper house as a check on the lower

- Strong governors with veto power over the legislature and substantial appointment authority

- Few or no restraints on individuals holding multiple positions in government

- The continuation of state-established religion

In Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New Hampshire, the resulting constitutions embodied:

- universal manhood suffrage, or minimal property requirements for

voting or holding office (New Jersey enfranchised some property-owning

widows, a step that it retracted 25 years later)

- strong, unicameral legislatures

- relatively weak governors without veto powers, and with little appointing authority

- prohibition against individuals holding multiple government posts

The radical provisions of Pennsylvania's constitution lasted only 14

years. In 1790, conservatives gained power in the state legislature,

called a new constitutional convention, and rewrote the constitution.

The new constitution substantially reduced universal male suffrage, gave

the governor veto power and patronage appointment authority, and added

an upper house with substantial wealth qualifications to the unicameral

legislature. Thomas Paine called it a constitution unworthy of America.

Independence and Union

In April 1776, the

North Carolina Provincial Congress issued the

Halifax Resolves explicitly authorizing its delegates to vote for independence.

By June, nine Provincial Congresses were ready for independence; one by

one, the last four fell into line: Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland,

and New York.

Richard Henry Lee

was instructed by the Virginia legislature to propose independence, and

he did so on June 7, 1776. On June 11, a committee was created to draft

a document explaining the justifications for separation from Britain.

After securing enough votes for passage, independence was voted for on

July 2.

The

Declaration of Independence was drafted largely by

Thomas Jefferson and presented by the committee; it was unanimously adopted by the entire Congress on July 4,

and each colony became independent and autonomous. The next step was to

form a union to facilitate international relations and alliances.

The Second Continental Congress approved the "

Articles of Confederation"

for ratification by the states on November 15, 1777; the Congress

immediately began operating under the Articles' terms, providing a

structure of shared sovereignty during prosecution of the war and

facilitating international relations and alliances with France and

Spain. The articles were ratified on March 1, 1781. At that point, the

Continental Congress was dissolved and a new government of the

United States in Congress Assembled took its place on the following day, with

Samuel Huntington as presiding officer.

Defending the Revolution

British return: 1776–1777

According to British historian

Jeremy Black,

the British had significant advantages, including a highly trained

army, the world's largest navy, and an efficient system of public

finance that could easily fund the war. However, they seriously

misunderstood the depth of support for the American Patriot position and

ignored the advice of General Gage, misinterpreting the situation as

merely a large-scale riot. The British government believed that they

could overawe the Americans by sending a large military and naval force,

forcing them to be loyal again:

Convinced that the Revolution was

the work of a full few miscreants who had rallied an armed rabble to

their cause, they expected that the revolutionaries would be

intimidated .... Then the vast majority of Americans, who were loyal but

cowed by the terroristic tactics ... would rise up, kick out the

rebels, and restore loyal government in each colony.

Washington forced the British out of Boston in the spring of 1776,

and neither the British nor the Loyalists controlled any significant

areas. The British, however, were massing forces at their naval base at

Halifax, Nova Scotia. They returned in force in July 1776, landing in New York and defeating Washington's Continental Army in August at the

Battle of Brooklyn. Following that victory, they requested a meeting with representatives from Congress to negotiate an end to hostilities.

A delegation including John Adams and Benjamin Franklin met British admiral

Richard Howe on

Staten Island in New York Harbor on September 11 in what became known as the

Staten Island Peace Conference.

Howe demanded that the Americans retract the Declaration of

Independence, which they refused to do, and negotiations ended. The

British then

seized New York City

and nearly captured Washington's army. They made New York their main

political and military base of operations, holding it until

November 1783. The city became the destination for Loyalist refugees and a focal point of Washington's

intelligence network.

The British also took New Jersey, pushing the Continental Army into Pennsylvania. Washington

crossed the Delaware River back into New Jersey in a surprise attack in late December 1776 and defeated the

Hessian and British armies at

Trenton and

Princeton,

thereby regaining control of most of New Jersey. The victories gave an

important boost to Patriots at a time when morale was flagging, and they

have become iconic events of the war.

In 1777, the British sent Burgoyne's invasion force from Canada

south to New York to seal off New England. Their aim was to isolate New

England, which the British perceived as the primary source of agitation.

Rather than move north to support Burgoyne, the British army in New

York City went to Philadelphia in a major case of mis-coordination,

capturing it from Washington. The invasion army under

Burgoyne was much too slow and became trapped in northern New York state. It surrendered after the

Battles of Saratoga in October 1777. From early October 1777 until November 15, a siege distracted British troops at

Fort Mifflin,

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and allowed Washington time to preserve the

Continental Army by safely leading his troops to harsh winter quarters

at

Valley Forge.

Prisoners

In August 1775, George III declared Americans to be traitors to the

Crown if they took up arms against royal authority. There were thousands

of British and Hessian soldiers in American hands following their

surrender at the

Battles of Saratoga

in October 1777. Lord Germain took a hard line, but the British

generals on American soil never held treason trials and treated captured

American soldiers as prisoners of war.

The dilemma was that tens of thousands of Loyalists were under American

control and American retaliation would have been easy. The British

built much of their strategy around using these Loyalists.

The British maltreated the prisoners whom they held, resulting in more

deaths to American prisoners of war than from combat operations. At the end of the war, both sides released their surviving prisoners.

American alliances after 1778

The capture of a British army at Saratoga encouraged the French to

formally enter the war in support of Congress, and Benjamin Franklin

negotiated a permanent military alliance in early 1778; France thus

became the first foreign nation to officially recognize the Declaration

of Independence. On February 6, 1778, the United States and France

signed the

Treaty of Amity and Commerce and the

Treaty of Alliance.

William Pitt

spoke out in Parliament urging Britain to make peace in America and to

unite with America against France, while British politicians who had

sympathized with colonial grievances now turned against the Americans

for allying with Britain's rival and enemy.

The Spanish and the Dutch became allies of the French in 1779 and

1780 respectively, forcing the British to fight a global war without

major allies and requiring it to slip through a combined blockade of the

Atlantic. Britain began to view the American war for independence as

merely one front in a wider war,

and the British chose to withdraw troops from America to reinforce the

sugar-producing Caribbean colonies, which were more lucrative to British

investors. British commander Sir

Henry Clinton evacuated Philadelphia and returned to New York City. General Washington intercepted him in the

Battle of Monmouth Court House,

the last major battle fought in the north. After an inconclusive

engagement, the British retreated to New York City. The northern war

subsequently became a stalemate, as the focus of attention shifted to

the smaller southern theater.

Hessian troops hired out to the British by their German sovereigns

The British move South, 1778–1783

The British strategy in America now concentrated on a campaign in the

southern states. With fewer regular troops at their disposal, the

British commanders saw the "southern strategy" as a more viable plan, as

they perceived the south as strongly Loyalist with a large population

of recent immigrants and large numbers of slaves who might be captured

or run away to join the British.

Beginning in late December 1778, they captured

Savannah and controlled the

Georgia coastline. In 1780, they launched a fresh invasion and

took Charleston, as well. A significant victory at the

Battle of Camden

meant that royal forces soon controlled most of Georgia and South

Carolina. The British set up a network of forts inland, hoping that the

Loyalists would rally to the flag.

Not enough Loyalists turned out, however, and the British had to fight

their way north into North Carolina and Virginia with a severely

weakened army. Behind them, much of the territory that they had already

captured dissolved into a chaotic guerrilla war, fought predominantly

between bands of Loyalists and American militia, which negated many of

the gains that the British had previously made.

Surrender at Yorktown (1781)

The British army under Cornwallis marched to

Yorktown, Virginia, where they expected to be rescued by a British fleet. The fleet did arrive, but so did a larger French fleet. The French were victorious in the

Battle of the Chesapeake,

and the British fleet returned to New York for reinforcements, leaving

Cornwallis trapped. In October 1781, the British surrendered their

second invading army of the war under a siege by the combined French and

Continental armies commanded by Washington.

The end of the war

Historians continue to debate whether the odds were long or short for American victory.

John E. Ferling says that the odds were so long that the American victory was "almost a miracle". On the other hand,

Joseph Ellis

says that the odds favored the Americans, and asks whether there ever

was any realistic chance for the British to win. He argues that this

opportunity came only once, in the summer of 1776, and the British

failed that test. Admiral Howe and his brother General Howe "missed

several opportunities to destroy the Continental Army .... Chance, luck,

and even the vagaries of the weather played crucial roles." Ellis's

point is that the strategic and tactical decisions of the Howes were

fatally flawed because they underestimated the challenges posed by the

Patriots. Ellis concludes that, once the Howe brothers failed, the

opportunity "would never come again" for a British victory.

Support for the conflict had never been strong in Britain, where

many sympathized with the Americans, but now it reached a new low.

King George wanted to fight on, but his supporters lost control of

Parliament and they launched no further offensives in America. War erupted between America and Britain three decades later with the

War of 1812, which firmly established the permanence of the United States and its complete autonomy.

Washington did not know whether the British might reopen

hostilities after Yorktown. They still had 26,000 troops occupying New

York City, Charleston, and Savannah, together with a powerful fleet. The

French army and navy departed, so the Americans were on their own in

1782–83. The treasury was empty, and the unpaid soldiers were growing restive, almost to the point of mutiny or possible

coup d'état. Washington dispelled the unrest among officers of the

Newburgh Conspiracy in 1783, and Congress subsequently created the promise of a five years bonus for all officers.

Paris peace treaty

During negotiations in Paris, the American delegation discovered that

France supported American independence but no territorial gains, hoping

to confine the new nation to the area east of the Appalachian

Mountains. The Americans opened direct secret negotiations with London,

cutting out the French. British Prime Minister

Lord Shelburne was in charge of the British negotiations, and he saw a chance to make the United States a valuable economic partner.

The US obtained all the land east of the Mississippi River, south of

Canada, and north of Florida. It gained fishing rights off Canadian

coasts, and agreed to allow British merchants and Loyalists to recover

their property. Prime Minister Shelburne foresaw highly profitable

two-way trade between Britain and the rapidly growing United States,

which did come to pass. The blockade was lifted and all British

interference had been driven out, and American merchants were free to

trade with any nation anywhere in the world.

The British largely abandoned their American Indian allies, who

were not a party to this treaty and did not recognize it until they were

defeated militarily by the United States. However, the British did sell

them munitions and maintain forts in American territory until the

Jay Treaty of 1795.

Losing the war and the Thirteen Colonies was a shock to Britain. The war revealed the limitations of Britain's

fiscal-military state

when they discovered that they suddenly faced powerful enemies with no

allies, and they were dependent on extended and vulnerable transatlantic

lines of communication. The defeat heightened dissension and escalated

political antagonism to the King's ministers. Inside Parliament, the

primary concern changed from fears of an over-mighty monarch to the

issues of representation, parliamentary reform, and government

retrenchment. Reformers sought to destroy what they saw as widespread

institutional corruption,

and the result was a crisis from 1776 to 1783. The peace in 1783 left

France financially prostrate, while the British economy boomed thanks to

the return of American business. The crisis ended after 1784 thanks to

the King's shrewdness in outwitting

Charles James Fox (the leader of the

Fox-North Coalition), and renewed confidence in the system engendered by the leadership of Prime Minister

William Pitt. Some historians suggest that loss of the American colonies enabled Britain to deal with the

French Revolution with more unity and better organization than would otherwise have been the case. Britain turned towards Asia, the Pacific, and later Africa with subsequent exploration leading to the rise of the

Second British Empire.

Finance

Britain's war against the Americans, the French, and the Spanish cost

about £100 million, and the Treasury borrowed 40-percent of the money

that it needed. Heavy spending brought France to the

verge of bankruptcy and revolution,

while the British had relatively little difficulty financing their war,

keeping their suppliers and soldiers paid, and hiring tens of thousands

of German soldiers.

Britain had a sophisticated financial system based on the wealth of

thousands of landowners who supported the government, together with

banks and financiers in London. The British tax system collected about

12 percent of the GDP in taxes during the 1770s.

In sharp contrast, Congress and the American states had no end of difficulty financing the war.

In 1775, there was at most 12 million dollars in gold in the colonies,

not nearly enough to cover current transactions, let alone finance a

major war. The British made the situation much worse by imposing a tight

blockade on every American port, which cut off almost all imports and

exports. One partial solution was to rely on volunteer support from

militiamen and donations from patriotic citizens.

Another was to delay actual payments, pay soldiers and suppliers in

depreciated currency, and promise that it would be made good after the

war. Indeed, the soldiers and officers were given land grants in 1783 to

cover the wages that they had earned but had not been paid during the

war. The national government did not have a strong leader in financial

matters until 1781, when

Robert Morris was named

Superintendent of Finance of the United States. Morris used a French loan in 1782 to set up the private

Bank of North America to finance the war. He reduced the

civil list,

saved money by using competitive bidding for contracts, tightened

accounting procedures, and demanded the national government's full share

of money and supplies from the individual states.

Congress used four main methods to cover the cost of the war, which cost about 66 million dollars in specie (gold and silver).

Congress made issues of paper money in 1775–1780 and in 1780–81. The

first issue amounted to 242 million dollars. This paper money would

supposedly be redeemed for state taxes, but the holders were eventually

paid off in 1791 at the rate of one cent on the dollar. By 1780, the

paper money was "not worth a Continental", as people said.

The skyrocketing inflation was a hardship on the few people who had

fixed incomes, but 90 percent of the people were farmers and were not

directly affected by it. Debtors benefited by paying off their debts

with depreciated paper. The greatest burden was borne by the soldiers of

the Continental Army whose wages were usually paid late and declined in

value every month, weakening their morale and adding to the hardships

of their families.

Beginning in 1777, Congress repeatedly asked the states to

provide money, but the states had no system of taxation and were of

little help. By 1780, Congress was making requisitions for specific

supplies of corn, beef, pork, and other necessities, an inefficient

system which barely kept the army alive.

Starting in 1776, the Congress sought to raise money by loans from

wealthy individuals, promising to redeem the bonds after the war. The

bonds were redeemed in 1791 at face value, but the scheme raised little

money because Americans had little specie, and many of the rich

merchants were supporters of the Crown. The French secretly supplied the

Americans with money, gunpowder, and munitions to weaken Great Britain;

the subsidies continued when France entered the war in 1778, and the

French government and Paris bankers lent large sums to the American war

effort. The Americans struggled to pay off the loans; they ceased

making interest payments to France in 1785 and defaulted on installments

due in 1787. In 1790, however, they resumed regular payments on their

debts to the French, and settled their accounts with the French government in 1795 by selling the debt to James Swan, an American banker.

Concluding the Revolution

Creating a "more perfect union" and guaranteeing rights

The war ended in 1783 and was followed by a period of prosperity. The

national government was still operating under the Articles of

Confederation and settled the issue of the western territories, which

the states ceded to Congress. American settlers moved rapidly into those

areas, with Vermont, Kentucky, and Tennessee becoming states in the

1790s.

However, the national government had no money either to pay the

war debts owed to European nations and the private banks, or to pay

Americans who had been given millions of dollars of promissory notes for

supplies during the war. Nationalists led by Washington, Alexander

Hamilton, and other veterans feared that the new nation was too fragile

to withstand an international war, or even internal revolts such as the

Shays' Rebellion of 1786 in Massachusetts. They convinced Congress to call the

Philadelphia Convention in 1787 and named their party the Federalist party. The Convention adopted a new

Constitution which provided for a much stronger federal government, including an effective executive in a

check-and-balance system with the judiciary and legislature.

The Constitution was ratified in 1788, after a fierce debate in the

states over the proposed new government. The new government under

President George Washington took office in New York in March 1789.

James Madison

spearheaded Congressional amendments to the Constitution as assurances

to those cautious about federal power, guaranteeing many of the

inalienable rights that formed a foundation for the revolution, and Rhode Island was the final state to ratify the Constitution in 1791.

National debt

The national debt fell into three categories after the American

Revolution. The first was the $12 million owed to foreigners, mostly

money borrowed from France. There was general agreement to pay the

foreign debts at full value. The national government owed $40 million

and state governments owed $25 million to Americans who had sold food,

horses, and supplies to the Patriot forces. There were also other debts

which consisted of

promissory notes

issued during the war to soldiers, merchants, and farmers who accepted

these payments on the premise that the new Constitution would create a

government that would pay these debts eventually.

The war expenses of the individual states added up to $114 million, compared to $37 million by the central government.

In 1790, Congress combined the remaining state debts with the foreign

and domestic debts into one national debt totaling $80 million at the

recommendation of first Secretary of the Treasury

Alexander Hamilton.

Everyone received face value for wartime certificates, so that the

national honor would be sustained and the national credit established.

Ideology and factions

The population of the Thirteen States was not homogeneous in

political views and attitudes. Loyalties and allegiances varied widely

within regions and communities and even within families, and sometimes

shifted during the Revolution.

Ideology behind the Revolution

The American Enlightenment was a critical precursor of the American

Revolution. Chief among the ideas of the American Enlightenment were the

concepts of natural law, natural rights, consent of the governed,

individualism, property rights, self-ownership, self-determination,

liberalism, republicanism, and defense against corruption. A growing

number of American colonists embraced these views and fostered an

intellectual environment which led to a new sense of political and

social identity.

Liberalism

John Locke's

(1632–1704) ideas on liberty influenced the political thinking behind

the revolution, especially through his indirect influence on English

writers such as

John Trenchard,

Thomas Gordon, and

Benjamin Hoadly, whose political ideas had a strong influence on the American Patriots.

Locke is often referred to as "the philosopher of the American

Revolution" due to his work in the Social Contract and Natural Rights

theories that underpinned the Revolution's political ideology. Locke's

Two Treatises of Government

published in 1689 was especially influential. He argued that all humans

were created equally free, and governments therefore needed the

"consent of the governed". In late eighteenth-century America, belief was still widespread in "equality by creation" and "rights by creation".

Republicanism

The American ideology called "republicanism" was inspired by the

Whig party in Great Britain which openly criticized the corruption within the British government. Americans were increasingly embracing republican values, seeing Britain as corrupt and hostile to American interests. The colonists associated political corruption with luxury and inherited aristocracy, which they condemned.

The Founding Fathers were strong advocates of republican values, particularly

Samuel Adams,

Patrick Henry,

John Adams,

Benjamin Franklin,

Thomas Jefferson,

Thomas Paine,

George Washington,

James Madison, and

Alexander Hamilton,

which required men to put civic duty ahead of their personal desires.

Men had a civic duty to be prepared and willing to fight for the rights

and liberties of their countrymen. John Adams wrote to

Mercy Otis Warren

in 1776, agreeing with some classical Greek and Roman thinkers: "Public

Virtue cannot exist without private, and public Virtue is the only

Foundation of Republics." He continued:

There must be a positive Passion

for the public good, the public Interest, Honour, Power, and Glory,

established in the Minds of the People, or there can be no Republican

Government, nor any real Liberty. And this public Passion must be

Superior to all private Passions. Men must be ready, they must pride

themselves, and be happy to sacrifice their private Pleasures, Passions,

and Interests, nay their private Friendships and dearest connections,

when they Stand in Competition with the Rights of society.

Thomas Paine published his pamphlet

Common Sense

in January 1776, after the Revolution had started. It was widely

distributed and often read aloud in taverns, contributing significantly

to spreading the ideas of republicanism and liberalism together,

bolstering enthusiasm for separation from Great Britain and encouraging

recruitment for the Continental Army. Paine offered a solution for Americans alarmed by the threat of tyranny.

Protestant Dissenters and the Great Awakening

Protestant churches that had separated from the Church of England

(called "dissenters") were the "school of democracy", in the words of

historian Patricia Bonomi. Before the Revolution, the

Southern Colonies and three of the

New England Colonies had officially established churches: Congregational in

Massachusetts Bay,

Connecticut, and

New Hampshire, and Anglican in

Maryland,

Virginia,

North-Carolina,

South Carolina, and

Georgia.

New York,

New Jersey,

Pennsylvania,

Delaware, and the

Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations had no officially established churches. Church membership statistics from the period are unreliable and scarce,

but what little data exists indicates that Anglicans were not in the

majority, not even in the colonies where the Church of England was the

established church, and they probably did not comprise even 30 percent

of the population (with the possible exception of Virginia).

President

John Witherspoon of the College of New Jersey (now

Princeton University)

wrote widely circulated sermons linking the American Revolution to the

teachings of the Bible. Throughout the colonies, dissenting Protestant

ministers (Congregational, Baptist, and Presbyterian) preached

Revolutionary themes in their sermons, while most Church of England

clergymen preached loyalty to the king, the titular head of the English

state church.

Religious motivation for fighting tyranny transcended socioeconomic

lines to encompass rich and poor, men and women, frontiersmen and

townsmen, farmers and merchants.

The Declaration of Independence also referred to the "Laws of Nature

and of Nature's God" as justification for the Americans' separation from

the British monarchy. Most eighteenth-century Americans believed that

the entire universe ("nature") was God's creation

and he was "Nature's God". Everything was part of the "universal order

of things" which began with God and was directed by his providence.

Accordingly, the signers of the Declaration professed their "firm

reliance on the Protection of divine Providence", and they appealed to

"the Supreme Judge for the rectitude of our intentions".

George Washington was firmly convinced that he was an instrument of providence, to the benefit of the American people and of all humanity.

Historian

Bernard Bailyn

argues that the evangelicalism of the era challenged traditional

notions of natural hierarchy by preaching that the Bible teaches that

all men are equal, so that the true value of a man lies in his moral

behavior, not in his class. Kidd argues that religious

disestablishment,

belief in God as the source of human rights, and shared convictions

about sin, virtue, and divine providence worked together to unite

rationalists and evangelicals and thus encouraged a large proportion of

Americans to fight for independence from the Empire. Bailyn, on the

other hand, denies that religion played such a critical role. Alan Heimert argues that

New Light

anti-authoritarianism was essential to furthering democracy in colonial

American society, and set the stage for a confrontation with British

monarchical and aristocratic rule.

Class and psychology of the factions

John Adams concluded in 1818:

The Revolution was effected before

the war commenced. The Revolution was in the minds and hearts of the

people .... This radical change in the principles, opinions, sentiments,

and affections of the people was the real American Revolution.

In the mid-20th century, historian

Leonard Woods Labaree

identified eight characteristics of the Loyalists that made them

essentially conservative, opposite to the characteristics of the

Patriots.

Loyalists tended to feel that resistance to the Crown was morally

wrong, while the Patriots thought that morality was on their side. Loyalists were alienated when the Patriots resorted to violence, such as burning houses and

tarring and feathering.

Loyalists wanted to take a centrist position and resisted the Patriots'

demand to declare their opposition to the Crown. Many Loyalists had

maintained strong and long-standing relations with Britain, especially

merchants in port cities such as New York and Boston.

Many Loyalists felt that independence was bound to come eventually, but

they were fearful that revolution might lead to anarchy, tyranny, or

mob rule. In contrast, the prevailing attitude among Patriots was a

desire to seize the initiative. Labaree also wrote that Loyalists were pessimists who lacked the confidence in the future displayed by the Patriots.

Historians in the early 20th century such as

J. Franklin Jameson examined the class composition of the Patriot cause, looking for evidence of a class war inside the revolution. More recent historians have largely abandoned that interpretation, emphasizing instead the high level of ideological unity. Both Loyalists and Patriots were a "mixed lot",

but ideological demands always came first. The Patriots viewed

independence as a means to gain freedom from British oppression and

taxation and to reassert their basic rights. Most yeomen farmers,

craftsmen, and small merchants joined the Patriot cause to demand more

political equality. They were especially successful in Pennsylvania but

less so in New England, where John Adams attacked Thomas Paine's

Common Sense for the "absurd democratical notions" that it proposed.

King George III

The war became a personal issue for

the king,

fueled by his growing belief that British leniency would be taken as

weakness by the Americans. He also sincerely believed that he was

defending Britain's constitution against usurpers, rather than opposing

patriots fighting for their natural rights.

Patriots

Those who fought for independence were called "Patriots", "Whigs",

"Congress-men", or "Americans" during and after the war. They included a

full range of social and economic classes but were unanimous regarding

the need to defend the rights of Americans and uphold the principles of

republicanism in rejecting monarchy and aristocracy, while emphasizing

civic virtue by citizens. Newspapers were strongholds of patriotism

(although there were a few Loyalist papers) and printed many pamphlets,

announcements, patriotic letters, and pronouncements.

According to historian Robert Calhoon, 40– to 45-percent of the

white population in the Thirteen Colonies supported the Patriots' cause,

15– to 20-percent supported the Loyalists, and the remainder were

neutral or kept a low profile.

Mark Lender analyzes why ordinary people became insurgents against the

British, even if they were unfamiliar with the ideological reasons

behind the war. He concludes that such people held a sense of rights

which the British were violating, rights that stressed local autonomy,

fair dealing, and government by consent. They were highly sensitive to

the issue of tyranny, which they saw manifested in the British response

to the Boston Tea Party. The arrival in Boston of the British Army

heightened their sense of violated rights, leading to rage and demands

for revenge. They had faith that God was on their side. The signers of the Declaration of Independence were mostly well-educated, of British stock, and of the Protestant faith.

Loyalists

American Patriots mobbing a Loyalist in 1775–76

The consensus of scholars is that about 15– to 20-percent of the white population remained loyal to the British Crown.

Those who actively supported the king were known at the time as

"Loyalists", "Tories", or "King's men". The Loyalists never controlled

territory unless the British Army occupied it. They were typically

older, less willing to break with old loyalties, and often connected to

the Church of England; they included many established merchants with

strong business connections throughout the Empire, as well as royal

officials such as Thomas Hutchinson of Boston. There were 500 to 1,000

black loyalists,

slaves who escaped to British lines and joined the British army. Most

died of disease, but Britain took the survivors to Canada as free men.

The revolution could divide families, such as

William Franklin, son of Benjamin Franklin and royal governor of the

Province of New Jersey who remained loyal to the Crown throughout the war. He and his father never spoke again. Recent immigrants who had not been fully Americanized were also inclined to support the King, such as

Flora MacDonald, a Scottish settler in the backcountry.

After the war, the most of the approximately 500,000 Loyalists

remained in America and resumed normal lives. Some became prominent

American leaders, such as

Samuel Seabury.

Approximately 46,000 Loyalists relocated to Canada; others moved to

Britain (7,000), Florida, or the West Indies (9,000). The exiles

represented approximately two percent of the total population of the

colonies. Nearly all black loyalists left for Nova Scotia, Florida, or England, where they could remain free. Loyalists who left the South in 1783 took thousands of their slaves with them to be slaves in the British West Indies.

Neutrals

A minority of uncertain size tried to stay neutral in the war. Most

kept a low profile, but the Quakers were the most important group to

speak out for neutrality, especially in Pennsylvania. The Quakers

continued to do business with the British even after the war began, and

they were accused of supporting British rule, "contrivers and authors of

seditious publications" critical of the revolutionary cause. Most Quakers remained neutral, although

a sizeable number nevertheless participated to some degree.

Role of women

Women contributed to the American Revolution in many ways and were

involved on both sides. Formal politics did not include women, but

ordinary domestic behaviors became charged with political significance

as Patriot women confronted a war which permeated all aspects of

political, civil, and domestic life. They participated by boycotting

British goods, spying on the British, following armies as they marched,

washing, cooking, and mending for soldiers, delivering secret messages,

and even fighting disguised as men in a few cases, such as

Deborah Samson.

Mercy Otis Warren held meetings in her house and cleverly attacked Loyalists with her creative plays and histories.

Many women also acted as nurses and helpers, tending to the soldiers'

wounds and buying and selling goods for them. Some of these camp

followers even participated in combat, such as Madam John Turchin who

led her husband's regiment into battle.

Above all, women continued the agricultural work at home to feed their

families and the armies. They maintained their families during their

husbands' absences and sometimes after their deaths.

American women were integral to the success of the boycott of British goods,

as the boycotted items were largely household articles such as tea and

cloth. Women had to return to knitting goods and to spinning and weaving

their own cloth—skills that had fallen into disuse. In 1769, the women

of Boston produced 40,000 skeins of yarn, and 180 women in

Middletown, Massachusetts wove 20,522 yards (18,765 m) of cloth. Many women gathered food, money, clothes, and other supplies during the war to help the soldiers.

A woman's loyalty to her husband could become an open political act,

especially for women in America committed to men who remained loyal to

the King. Legal divorce, usually rare, was granted to Patriot women

whose husbands supported the King.

Other participants

Coin minted for

John Adams

in 1782 to celebrate The Netherlands' recognition of the United States

as an independent nation, one of three coins minted for him; all three

are in the coin collection of the

Teylers Museum

France and Spain

In early 1776, France set up a major program of aid to the Americans,

and the Spanish secretly added funds. Each country spent one million

"livres tournaises" to buy munitions. A dummy corporation run by

Pierre Beaumarchais

concealed their activities. American Patriots obtained some munitions

through the Dutch Republic, as well as French and Spanish ports in the

West Indies. Heavy expenditures and a weak taxation system pushed France toward bankruptcy.

Spain did not officially recognize the U.S. but it separately declared war on Britain on June 21, 1779.

Bernardo de Gálvez y Madrid, general of the Spanish forces in

New Spain,

also served as governor of Louisiana. He led an expedition of colonial

troops to force the British out of Florida and to keep open a vital

conduit for supplies.

American Indians

Most American Indians rejected pleas that they remain neutral and

instead supported the British Crown. The great majority of the 200,000

Indians east of the Mississippi distrusted the Colonists and supported

the British cause, hoping to forestall continued colonial expansion into

their territories. Those tribes closely involved in trade tended to side with the Patriots, although political factors were important, as well.

Most Indians did not participate directly in the war, except for warriors and bands associated with four of the

Iroquois

tribes in New York and Pennsylvania which allied with the British. The

British did have other allies, especially in the upper Midwest. They

provided Indians with funding and weapons to attack American outposts.

Some Indians tried to remain neutral, seeing little value in joining

what they perceived to be a European conflict, and fearing reprisals

from whichever side they opposed. The

Oneida and

Tuscarora tribes among the Iroquois of central and western New York supported the American cause. The British provided arms to Indians who were led by Loyalists in war parties to raid frontier settlements from the

Carolinas to New York. They killed many settlers on the frontier, especially in Pennsylvania and New York's Mohawk Valley.

In 1776,

Cherokee war parties attacked American Colonists all along the southern frontier of the uplands throughout the

Washington District, North Carolina (now Tennessee) and the Kentucky wilderness area. They would launch raids with roughly 200 warriors, as seen in the

Cherokee–American wars; they could not mobilize enough forces to invade Colonial areas without the help of allies, most often the

Creek. The

Chickamauga Cherokee under

Dragging Canoe allied themselves closely with the British, and fought on for an additional decade after the Treaty of Paris was signed.

Joseph Brant of the powerful

Mohawk

tribe in New York was the most prominent Indian leader against the

Patriot forces. In 1778 and 1780, he led 300 Iroquois warriors and 100

white Loyalists in multiple attacks on small frontier settlements in New

York and Pennsylvania, killing many settlers and destroying villages,

crops, and stores. The Seneca, Onondaga, and Cayuga of the Iroquois Confederacy also allied with the British against the Americans.

In 1779, the Americans forced the hostile Indians out of upstate New York when Washington sent an army under

John Sullivan which destroyed 40 empty Iroquois villages in central and western New York. The

Battle of Newtown

proved decisive, as the Patriots had an advantage of three-to-one, and

it ended significant resistance; there was little combat otherwise.

Sullivan systematically burned the empty villages and destroyed about

160,000 bushels of corn that composed the winter food supply. Facing

starvation and homeless for the winter, the Iroquois fled to Canada. The

British resettled them in Ontario, providing land grants as

compensation for some of their losses.

At the peace conference following the war, the British ceded

lands which they did not really control, and they did not consult their

Indian allies. They transferred control to the United States of all the

land east of the Mississippi and north of Florida. Calloway concludes:

Burned villages and crops, murdered

chiefs, divided councils and civil wars, migrations, towns and forts

choked with refugees, economic disruption, breaking of ancient

traditions, losses in battle and to disease and hunger, betrayal to

their enemies, all made the American Revolution one of the darkest

periods in American Indian history.

The British did not give up their forts until 1796 in the eastern

Midwest, stretching from Ohio to Wisconsin; they kept alive the dream of

forming a satellite Indian nation there, which they called a Neutral

Indian Zone. That goal was one of the causes of the

War of 1812.

Black Americans

Crispus Attucks was an iconic patriot; he was fatally shot by British soldiers in the

Boston Massacre of 1770 and is thus considered the first American killed in the Revolution

Free blacks in the North and South fought on both sides of the

Revolution, but most fought for the Patriots. Gary Nash reports that

there were about 9,000 black Patriots, counting the Continental Army and

Navy, state militia units, privateers, wagoneers in the Army, servants

to officers, and spies.

Ray Raphael notes that thousands did join the Loyalist cause, but "a

far larger number, free as well as slave, tried to further their

interests by siding with the patriots."

Crispus Attucks was shot dead by British soldiers in the

Boston Massacre in 1770 and is considered the first American casualty of the Revolutionary War.

Many black slaves sided with the Loyalists. Tens of thousands in

the South used the turmoil of war to escape, and the southern plantation

economies of South Carolina and Georgia were disrupted in particular.

During the Revolution, the British tried to turn slavery against the

Americans. Historian

David Brion Davis explains the difficulties with a policy of wholesale arming of the slaves:

But England greatly feared the effects of any such move on its own West Indies,

where Americans had already aroused alarm over a possible threat to

incite slave insurrections. The British elites also understood that an

all-out attack on one form of property could easily lead to an assault

on all boundaries of privilege and social order, as envisioned by

radical religious sects in Britain's seventeenth-century civil wars.

Davis underscores the British dilemma: "Britain, when confronted by

the rebellious American colonists, hoped to exploit their fear of slave

revolts while also reassuring the large number of slave-holding

Loyalists and wealthy Caribbean planters and merchants that their slave

property would be secure". The Colonists, however, accused the British of encouraging slave revolts.

American advocates of independence were commonly lampooned in

Great Britain for what was termed their hypocritical calls for freedom,

while many of their leaders were planters who held hundreds of slaves.

Samuel Johnson snapped, "how is it we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of the Negroes?" Benjamin Franklin countered by criticizing the British self-congratulation about "the freeing of one Negro" named

Somersett while they continued to permit the overall slave trade.

Phyllis Wheatley was a black poet who popularized the image of

Columbia to represent America. She came to public attention when her

Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral appeared in 1773.

The effects of the war were more dramatic in the South. In Virginia, royal governor Lord

Dunmore

recruited black men into the British forces with the promise of

freedom, protection for their families, and land grants. Tens of

thousands of slaves escaped to British lines throughout the South,

causing dramatic losses to slaveholders and disrupting cultivation and

harvesting of crops. For instance,

South Carolina

was estimated to have lost about 25,000 slaves to flight, migration, or

death—amounting to a third of its slave population. From 1770 to 1790,

the black proportion of the population (mostly slaves) in South Carolina

dropped from 60.5 percent to 43.8 percent, and from 45.2 percent to

36.1 percent in Georgia.

British forces gave transportation to 10,000 slaves when they evacuated

Savannah and

Charleston, carrying through on their promise. They evacuated and resettled more than 3,000

Black Loyalists

from New York to Nova Scotia, Upper Canada, and Lower Canada. Others

sailed with the British to England or were resettled as freedmen in the

West Indies of the Caribbean. But slaves carried to the Caribbean under

control of Loyalist masters generally remained slaves until British

abolition in its colonies in 1834. More than 1,200 of the Black

Loyalists of Nova Scotia later resettled in the British colony of Sierra

Leone, where they became leaders of the

Krio

ethnic group of Freetown and the later national government. Many of

their descendants still live in Sierra Leone, as well as other African

countries.

Effects of the Revolution

Loyalist expatriation

Tens of thousands of Loyalists left the United States following the war, and Maya Jasanoff estimates as many as 70,000.

Some migrated to Britain, but the great majority received land and

subsidies for resettlement in British colonies in North America,

especially

Quebec (concentrating in the

Eastern Townships),

Prince Edward Island, and

Nova Scotia. Britain created the colonies of Upper Canada (

Ontario) and

New Brunswick

expressly for their benefit, and the Crown awarded land to Loyalists as

compensation for losses in the United States. Britain wanted to develop

the frontier of Upper Canada on a British colonial model. Nevertheless,

approximately 85-percent of the Loyalists stayed in the United States

as American citizens, and some of the exiles later returned to the U.S.

Interpretations

Interpretations vary concerning the effect of the Revolution. Historians such as

Bernard Bailyn,

Gordon Wood, and

Edmund Morgan

view it as a unique and radical event which produced deep changes and

had a profound effect on world affairs, such as an increasing belief in

the principles of the Enlightenment. These were demonstrated by a

leadership and government that espoused protection of natural rights,

and a system of laws chosen by the people.

John Murrin, by contrast, argues that the definition of "the people" at

that time was mostly restricted to free men who passed a property

qualification.

This view argues that any significant gain of the revolution was

irrelevant in the short term to women, black Americans and slaves, poor

white men, youth, and American Indians.

Gordon Wood states:

- The American Revolution was integral to the changes occurring in

American society, politics and culture .... These changes were radical,

and they were extensive .... The Revolution not only radically changed

the personal and social relationships of people, including the position

of women, but also destroyed aristocracy as it'd been understood in the

Western world for at least two millennia.

Edmund Morgan has argued that, in terms of long-term impact on American society and values:

- The Revolution did revolutionize social relations. It did

displace the deference, the patronage, the social divisions that had

determined the way people viewed one another for centuries and still

view one another in much of the world. It did give to ordinary people a

pride and power, not to say an arrogance, that have continued to shock

visitors from less favored lands. It may have left standing a host of

inequalities that have troubled us ever since. But it generated the

egalitarian view of human society that makes them troubling and makes

our world so different from the one in which the revolutionists had

grown up.

Inspiring all colonies

After the Revolution, genuinely democratic politics became possible in the former colonies.

The rights of the people were incorporated into state constitutions.

Concepts of liberty, individual rights, equality among men and hostility