From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Asteroids are

minor planets, especially those of the

inner Solar System. The larger ones have also been called

planetoids. These terms have historically been applied to any astronomical object orbiting the

Sun that did not show the disc of a planet and was not observed to have the characteristics of an active

comet. As

minor planets in the outer Solar System

were discovered and found to have volatile-based surfaces that resemble

those of comets, they were often distinguished from asteroids of the

asteroid belt.

[1] In this article, the term "asteroid" refers to the minor planets of the inner Solar System including those co-orbital with

Jupiter.

There are millions of asteroids, many thought to be the shattered remnants of

planetesimals, bodies within the young Sun's

solar nebula that never grew large enough to become

planets.

[2] The large majority of known asteroids orbit in the asteroid belt between the orbits of

Mars and Jupiter, or are co-orbital with Jupiter (the

Jupiter trojans). However, other orbital families exist with significant populations, including the

near-Earth objects. Individual asteroids are classified by their characteristic

spectra, with the majority falling into three main groups:

C-type,

M-type, and

S-type. These were named after and are generally identified with

carbon-rich,

metallic, and

silicate (stony) compositions, respectively. The size of asteroids varies greatly, some reaching as much as

1000 km across.

Asteroids are differentiated from

comets and

meteoroids.

In the case of comets, the difference is one of composition: while

asteroids are mainly composed of mineral and rock, comets are composed

of dust and ice. In addition, asteroids formed closer to the sun,

preventing the development of the aforementioned cometary ice.

[3]

The difference between asteroids and meteoroids is mainly one of size:

meteoroids have a diameter of less than one meter, whereas asteroids

have a diameter of greater than one meter.

[4] Finally, meteoroids can be composed of either cometary or asteroidal materials.

[5]

Only one asteroid,

4 Vesta,

which has a relatively reflective surface, is normally visible to the

naked eye, and this only in very dark skies when it is favorably

positioned. Rarely, small asteroids passing close to Earth may be

visible to the naked eye for a short time.

[6] As of March 2016, the

Minor Planet Center

had data on more than 1.3 million objects in the inner and outer Solar

System, of which 750,000 had enough information to be given numbered

designations.

[7]

The

United Nations declared June 30 as International

Asteroid Day to educate the public about asteroids. The date of International

Asteroid Day commemorates the anniversary of the

Tunguska asteroid impact over Siberia, Russian Federation, on 30 June 1908.

[8][9]

Discovery

243 Ida and its moon Dactyl. Dactyl is the first satellite of an asteroid to be discovered.

The first asteroid to be discovered,

Ceres, was found in 1801 by

Giuseppe Piazzi, and was originally considered to be a new planet.

[note 1]

This was followed by the discovery of other similar bodies, which, with

the equipment of the time, appeared to be points of light, like stars,

showing little or no planetary disc, though readily distinguishable from

stars due to their apparent motions. This prompted the astronomer

Sir William Herschel to propose the term "asteroid",

[10] coined in Greek as ἀστεροειδής, or

asteroeidēs, meaning 'star-like, star-shaped', and derived from the Ancient Greek

ἀστήρ astēr

'star, planet'. In the early second half of the nineteenth century, the

terms "asteroid" and "planet" (not always qualified as "minor") were

still used interchangeably.

[note 2]

Historical methods

Asteroid discovery methods have dramatically improved over the past two centuries.

In the last years of the 18th century, Baron

Franz Xaver von Zach organized a group of 24 astronomers to search the sky for the missing planet predicted at about 2.8

AU from the Sun by the

Titius-Bode law, partly because of the discovery, by Sir

William Herschel in 1781, of the planet

Uranus at the distance predicted by the law. This task required that hand-drawn sky charts be prepared for all stars in the

zodiacal

band down to an agreed-upon limit of faintness. On subsequent nights,

the sky would be charted again and any moving object would, hopefully,

be spotted. The expected motion of the missing planet was about 30

seconds of arc per hour, readily discernible by observers.

The first object,

Ceres, was not discovered by a member of the group, but rather by accident in 1801 by

Giuseppe Piazzi, director of the observatory of

Palermo in

Sicily. He discovered a new star-like object in

Taurus and followed the displacement of this object during several nights. Later that year,

Carl Friedrich Gauss used these observations to calculate the orbit of this unknown object, which was found to be between the planets

Mars and

Jupiter. Piazzi named it after

Ceres, the Roman goddess of agriculture.

Three other asteroids (

2 Pallas,

3 Juno, and

4 Vesta)

were discovered over the next few years, with Vesta found in 1807.

After eight more years of fruitless searches, most astronomers assumed

that there were no more and abandoned any further searches.

However,

Karl Ludwig Hencke persisted, and began searching for more asteroids in 1830. Fifteen years later, he found

5 Astraea, the first new asteroid in 38 years. He also found

6 Hebe

less than two years later. After this, other astronomers joined in the

search and at least one new asteroid was discovered every year after

that (except the wartime year 1945). Notable asteroid hunters of this

early era were

J. R. Hind,

Annibale de Gasparis,

Robert Luther,

H. M. S. Goldschmidt,

Jean Chacornac,

James Ferguson,

Norman Robert Pogson,

E. W. Tempel,

J. C. Watson,

C. H. F. Peters,

A. Borrelly,

J. Palisa, the

Henry brothers and

Auguste Charlois.

In 1891,

Max Wolf pioneered the use of

astrophotography

to detect asteroids, which appeared as short streaks on long-exposure

photographic plates. This dramatically increased the rate of detection

compared with earlier visual methods: Wolf alone discovered 248

asteroids, beginning with

323 Brucia,

whereas only slightly more than 300 had been discovered up to that

point. It was known that there were many more, but most astronomers did

not bother with them, calling them "vermin of the skies",

[11] a phrase variously attributed to

Eduard Suess[12] and

Edmund Weiss.

[13] Even a century later, only a few thousand asteroids were identified, numbered and named.

Manual methods of the 1900s and modern reporting

Until 1998, asteroids were discovered by a four-step process. First, a region of the sky was

photographed by a wide-field

telescope, or

astrograph.

Pairs of photographs were taken, typically one hour apart. Multiple

pairs could be taken over a series of days. Second, the two films or

plates of the same region were viewed under a

stereoscope.

Any body in orbit around the Sun would move slightly between the pair

of films. Under the stereoscope, the image of the body would seem to

float slightly above the background of stars. Third, once a moving body

was identified, its location would be measured precisely using a

digitizing microscope. The location would be measured relative to known

star locations.

[14]

These first three steps do not constitute asteroid discovery: the observer has only found an apparition, which gets a

provisional designation,

made up of the year of discovery, a letter representing the half-month

of discovery, and finally a letter and a number indicating the

discovery's sequential number (example:

1998 FJ74).

The last step of discovery is to send the locations and time of observations to the

Minor Planet Center,

where computer programs determine whether an apparition ties together

earlier apparitions into a single orbit. If so, the object receives a

catalogue number and the observer of the first apparition with a

calculated orbit is declared the discoverer, and granted the honor of

naming the object subject to the approval of the

International Astronomical Union.

Computerized methods

There is increasing interest in identifying asteroids whose orbits cross

Earth's, and that could, given enough time, collide with Earth

(see Earth-crosser asteroids). The three most important groups of

near-Earth asteroids are the

Apollos,

Amors, and

Atens. Various

asteroid deflection strategies have been proposed, as early as the 1960s.

The

near-Earth asteroid

433 Eros had been discovered as long ago as 1898, and the 1930s brought a flurry of similar objects. In order of discovery, these were:

1221 Amor,

1862 Apollo,

2101 Adonis, and finally

69230 Hermes, which approached within 0.005

AU of

Earth in 1937. Astronomers began to realize the possibilities of Earth impact.

Two events in later decades increased the alarm: the increasing acceptance of the

Alvarez hypothesis that an

impact event resulted in the

Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction, and the 1994 observation of

Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 crashing into

Jupiter. The U.S. military also declassified the information that its

military satellites, built to

detect nuclear explosions, had detected hundreds of upper-atmosphere impacts by objects ranging from one to 10 metres across.

All these considerations helped spur the launch of highly efficient surveys that consist of Charge-Coupled Device (

CCD)

cameras and computers directly connected to telescopes. As of spring

2011, it was estimated that 89% to 96% of near-Earth asteroids one

kilometer or larger in diameter had been discovered.

[15] A list of teams using such systems includes:

[16]

The LINEAR system alone has discovered 138,393 asteroids, as of 20 September 2013.

[17] Among all the surveys, 4711 near-Earth asteroids have been discovered

[18] including over 600 more than 1 km (0.6 mi) in diameter.

Terminology

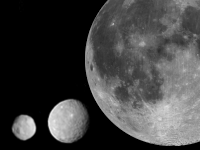

A composite image, to scale, of the asteroids that have been imaged at high resolution except

Ceres. As of 2011 they are, from largest to smallest:

4 Vesta,

21 Lutetia,

253 Mathilde,

243 Ida and its moon Dactyl,

433 Eros,

951 Gaspra,

2867 Šteins,

25143 Itokawa.

The largest asteroid in the previous image,

Vesta (left), with

Ceres (center) and the

Moon (right) shown to scale.

Traditionally, small bodies orbiting the Sun were classified as

comets, asteroids, or

meteoroids, with anything smaller than 10 meters across being called a meteoroid (such as in Beech and Steel's 1995 paper).

[19][20] The term "asteroid", from the Greek word for "star-like", never had a formal definition, with the broader term

minor planet being preferred by the

International Astronomical Union.

However, following the discovery of asteroids below 10 meters in

size, Rubin and Grossman in a 2010 paper revised the previous definition

of meteoroid to objects between 10

µm and 1 meter in size in order to maintain the distinction between asteroids and meteoroids.

[4] The smallest asteroids discovered (based on

absolute magnitude H) are

2008 TS26 with

H = 33.2 and

2011 CQ1 with

H = 32.1 both with an estimated size of about 1 meter.

[21]

In 2006, the term "

small Solar System body" was also introduced to cover both most minor planets and comets.

[22][23]

Other languages prefer "planetoid" (Greek for "planet-like"), and this

term is occasionally used in English especially for larger minor planets

such as the

dwarf planets as well as an alternative for asteroids since they are not star-like.

[24] The word "

planetesimal"

has a similar meaning, but refers specifically to the small building

blocks of the planets that existed when the Solar System was forming.

The term "planetule" was coined by the geologist

William Daniel Conybeare to describe minor planets,

[25] but is not in common use. The three largest objects in the asteroid belt,

Ceres,

Pallas, and

Vesta, grew to the stage of

protoplanets. Ceres is a

dwarf planet, the only one in the inner Solar System.

When found, asteroids were seen as a class of objects distinct from

comets, and there was no unified term for the two until "small Solar

System body" was coined in 2006. The main difference between an asteroid

and a comet is that a comet shows a coma due to

sublimation

of near surface ices by solar radiation. A few objects have ended up

being dual-listed because they were first classified as minor planets

but later showed evidence of cometary activity. Conversely, some

(perhaps all) comets are eventually depleted of their surface

volatile ices

and become asteroid-like. A further distinction is that comets

typically have more eccentric orbits than most asteroids; most

"asteroids" with notably eccentric orbits are probably dormant or

extinct comets.

[26]

For almost two centuries, from the discovery of

Ceres in 1801 until the discovery of the first

centaur,

Chiron, in 1977, all known asteroids spent most of their time at or within the orbit of Jupiter, though a few such as

Hidalgo

ventured far beyond Jupiter for part of their orbit. When astronomers

started finding more small bodies that permanently resided further out

than Jupiter, now called

centaurs,

they numbered them among the traditional asteroids, though there was

debate over whether they should be considered asteroids or as a new type

of object. Then, when the first

trans-Neptunian object (other than

Pluto),

1992 QB1,

was discovered in 1992, and especially when large numbers of similar

objects started turning up, new terms were invented to sidestep the

issue:

Kuiper-belt object,

trans-Neptunian object,

scattered-disc object,

and so on. These inhabit the cold outer reaches of the Solar System

where ices remain solid and comet-like bodies are not expected to

exhibit much cometary activity; if centaurs or trans-Neptunian objects

were to venture close to the Sun, their volatile ices would sublimate,

and traditional approaches would classify them as comets and not

asteroids.

The innermost of these are the

Kuiper-belt objects, called "objects" partly to avoid the need to classify them as asteroids or comets.

[27] They are thought to be predominantly comet-like in composition, though some may be more akin to asteroids.

[28]

Furthermore, most do not have the highly eccentric orbits associated

with comets, and the ones so far discovered are larger than traditional

comet nuclei. (The much more distant

Oort cloud

is hypothesized to be the main reservoir of dormant comets.) Other

recent observations, such as the analysis of the cometary dust collected

by the

Stardust probe, are increasingly blurring the distinction between comets and asteroids,

[29] suggesting "a continuum between asteroids and comets" rather than a sharp dividing line.

[30]

The minor planets beyond Jupiter's orbit are sometimes also called "asteroids", especially in popular presentations.

[31]

However, it is becoming increasingly common for the term "asteroid" to

be restricted to minor planets of the inner Solar System.

[27] Therefore, this article will restrict itself for the most part to the classical asteroids: objects of the

asteroid belt,

Jupiter trojans, and

near-Earth objects.

When the IAU introduced the class

small Solar System bodies in 2006 to include most objects previously classified as minor planets and comets, they created the class of

dwarf planets

for the largest minor planets—those that have enough mass to have

become ellipsoidal under their own gravity. According to the IAU, "the

term 'minor planet' may still be used, but generally the term 'Small

Solar System Body' will be preferred."

[32] Currently only the largest object in the asteroid belt,

Ceres, at about 950 km (590 mi) across, has been placed in the dwarf planet category.

Formation

Artist’s impression shows how an asteroid is torn apart by the strong gravity of a

white dwarf.

[33]

It is thought that

planetesimals in the asteroid belt evolved much like the rest of the

solar nebula until Jupiter neared its current mass, at which point excitation from

orbital resonances

with Jupiter ejected over 99% of planetesimals in the belt. Simulations

and a discontinuity in spin rate and spectral properties suggest that

asteroids larger than approximately 120 km (75 mi) in diameter

accreted

during that early era, whereas smaller bodies are fragments from

collisions between asteroids during or after the Jovian disruption.

[34] Ceres and Vesta grew large enough to melt and

differentiate, with heavy metallic elements sinking to the core, leaving rocky minerals in the crust.

[35]

In the

Nice model, many

Kuiper-belt objects

are captured in the outer asteroid belt, at distances greater than 2.6

AU. Most were later ejected by Jupiter, but those that remained may be

the

D-type asteroids, and possibly include Ceres.

[36]

Distribution within the Solar System

Various dynamical groups of asteroids have been discovered orbiting

in the inner Solar System. Their orbits are perturbed by the gravity of

other bodies in the Solar System and by the

Yarkovsky effect. Significant populations include:

Asteroid belt

The majority of known asteroids orbit within the asteroid belt between the orbits of

Mars and

Jupiter, generally in relatively low-

eccentricity

(i.e. not very elongated) orbits. This belt is now estimated to contain

between 1.1 and 1.9 million asteroids larger than 1 km (0.6 mi) in

diameter,

[37] and millions of smaller ones. These asteroids may be remnants of the

protoplanetary disk, and in this region the

accretion of

planetesimals into planets during the formative period of the Solar System was prevented by large gravitational perturbations by

Jupiter.

Trojans

Trojans

are populations that share an orbit with a larger planet or moon, but

do not collide with it because they orbit in one of the two

Lagrangian points of stability,

L4 and L5, which lie 60° ahead of and behind the larger body.

The most significant population of trojans are the

Jupiter trojans.

Although fewer Jupiter trojans have been discovered as of 2010, it is

thought that they are as numerous as the asteroids in the asteroid belt.

A couple of trojans have also been found orbiting with

Mars.

[note 3]

Near-Earth asteroids

Near-Earth asteroids, or NEAs, are asteroids that have orbits that

pass close to that of Earth. Asteroids that actually cross Earth's

orbital path are known as

Earth-crossers. As of June 2016, 14,464 near-Earth asteroids are known

[15] and the number over one kilometre in diameter is estimated to be 900–1,000.

Frequency of

bolides, small asteroids roughly 1 to 20 meters in diameter impacting Earth's atmosphere.

Characteristics

Size distribution

Sizes of the first ten asteroids to be discovered, compared to the Moon

Asteroids vary greatly in size, from almost

1000 km for the largest down to rocks just 1 meter across.

[note 4]

The three largest are very much like miniature planets: they are

roughly spherical, have at least partly differentiated interiors,

[38] and are thought to be surviving

protoplanets. The vast majority, however, are much smaller and are irregularly shaped; they are thought to be either surviving

planetesimals or fragments of larger bodies.

The

dwarf planet Ceres is by far the largest asteroid, with a diameter of 975 km (610 mi). The next largest are

4 Vesta and

2 Pallas,

both with diameters of just over 500 km (300 mi). Vesta is the only

main-belt asteroid that can, on occasion, be visible to the naked eye.

On some rare occasions, a near-Earth asteroid may briefly become visible

without technical aid; see

99942 Apophis.

The mass of all the objects of the

asteroid belt, lying between the orbits of

Mars and

Jupiter, is estimated to be about 2.8–

3.2×1021 kg, or about 4% of the mass of the Moon. Of this,

Ceres comprises

0.95×1021 kg, a third of the total.

[39] Adding in the next three most massive objects,

Vesta (9%),

Pallas (7%), and

Hygiea (3%), brings this figure up to 51%; whereas the three after that,

511 Davida (1.2%),

704 Interamnia (1.0%), and

52 Europa

(0.9%), only add another 3% to the total mass. The number of asteroids

then increases rapidly as their individual masses decrease.

The number of asteroids decreases markedly with size. Although this generally follows a

power law, there are 'bumps' at

5 km and

100 km, where more asteroids than expected from a

logarithmic distribution are found.

[40]

The asteroids of the Solar System, categorized by size and number

Approximate number of asteroids (N) larger than a certain diameter (D)

| D |

100 m |

300 m |

500 m |

1 km |

3 km |

5 km |

10 km |

30 km |

50 km |

100 km |

200 km |

300 km |

500 km |

900 km |

| N |

~25000000 |

4000000 |

2000000 |

750000 |

200000 |

90000 |

10000 |

1100 |

600 |

200 |

30 |

5 |

3 |

1 |

Largest asteroids

Although their location in the asteroid belt excludes them from planet status, the three largest objects,

Ceres,

Vesta, and

Pallas, are intact

protoplanets that share many characteristics common to planets, and are atypical compared to the majority of "potato"-shaped asteroids.

Ceres is the only asteroid with a fully ellipsoidal shape and hence the only one that is a

dwarf planet.

[43] It has a much higher

absolute magnitude than the other asteroids, of around 3.32,

[44] and may possess a surface layer of ice.

[45] Like the planets, Ceres is differentiated: it has a crust, a mantle and a core.

[45] No meteorites from Ceres have been found on Earth.

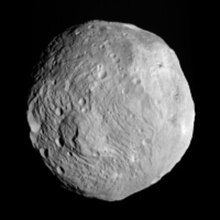

Vesta, too, has a differentiated interior, though it formed inside the Solar System's

frost line, and so is devoid of water;

[46] its composition is mainly of basaltic rock such as olivine.

[47] Aside from the large crater at its southern pole,

Rheasilvia, Vesta also has an ellipsoidal shape. Vesta is the parent body of the

Vestian family and other

V-type asteroids, and is the source of the

HED meteorites, which constitute 5% of all meteorites on Earth.

Pallas is unusual in that, like

Uranus, it rotates on its side, with its axis of rotation tilted at high angles to its orbital plane.

[48] Its composition is similar to that of Ceres: high in carbon and silicon, and perhaps partially differentiated.

[49] Pallas is the parent body of the

Palladian family of asteroids.

The fourth-most-massive asteroid,

Hygiea, is the largest carbonaceous asteroid and, unlike the other largest asteroids, lies relatively close to the

plane of the ecliptic.

[50] It is the largest member and presumed parent body of the

Hygiean family of asteroids. Between them, the four largest asteroids constitute half the mass of the asteroid belt.

| Attributes of largest asteroids |

| Name |

Orbital

radius (AU) |

Orbital period

(years) |

Inclination

to ecliptic |

Orbital

eccentricity |

Diameter

(km) |

Diameter

(% of Moon) |

Mass

(×1018 kg) |

Mass

(% of Ceres) |

Density[51]

g/cm3 |

Rotation

period

(hr) |

Axial tilt |

Surface

temperature |

| Vesta |

2.36 |

3.63 |

7.1° |

0.089 |

573×557×446

(mean 525) |

15% |

260 |

28% |

3.44 ± 0.12 |

5.34 |

29° |

85–270 K |

| Ceres |

2.77 |

4.60 |

10.6° |

0.079 |

975×975×909

(mean 952) |

28% |

940 |

100% |

2.12 ± 0.04 |

9.07 |

≈ 3° |

167 K |

| Pallas |

2.77 |

4.62 |

34.8° |

0.231 |

580×555×500

(mean 545) |

16% |

210 |

22% |

2.71 ± 0.11 |

7.81 |

≈ 80° |

164 K |

| Hygiea |

3.14 |

5.56 |

3.8° |

0.117 |

530×407×370

(mean 430) |

12% |

87 |

9% |

2.76 ± 1.2 |

27.6 |

≈ 60° |

164 K |

Rotation

Measurements

of the rotation rates of large asteroids in the asteroid belt show that

there is an upper limit. No asteroid with a diameter larger than 100

meters has a rotation period smaller than 2.2 hours. For asteroids

rotating faster than approximately this rate, the inertial force at the

surface is greater than the gravitational force, so any loose surface

material would be flung out. However, a solid object should be able to

rotate much more rapidly. This suggests that most asteroids with a

diameter over 100 meters are

rubble piles formed through accumulation of debris after collisions between asteroids.

[52]

Composition

Cratered terrain on 4 Vesta

The physical composition of asteroids is varied and in most cases

poorly understood. Ceres appears to be composed of a rocky core covered

by an icy mantle, where Vesta is thought to have a

nickel-iron core,

olivine mantle, and basaltic crust.

[53] 10 Hygiea, however, which appears to have a uniformly primitive composition of

carbonaceous chondrite,

is thought to be the largest undifferentiated asteroid. Most of the

smaller asteroids are thought to be piles of rubble held together

loosely by gravity, though the largest are probably solid. Some

asteroids have

moons or are co-orbiting

binaries: Rubble piles, moons, binaries, and scattered

asteroid families are thought to be the results of collisions that disrupted a parent asteroid.

Asteroids contain traces of

amino acids

and other organic compounds, and some speculate that asteroid impacts

may have seeded the early Earth with the chemicals necessary to initiate

life, or may have even brought life itself to Earth

(also see panspermia).

[54] In August 2011, a report, based on

NASA studies with

meteorites found on

Earth, was published suggesting

DNA and

RNA components (

adenine,

guanine and related

organic molecules) may have been formed on asteroids and

comets in

outer space.

[55][56][57]

Asteroid collision – building planets (artist concept).

Composition is calculated from three primary sources:

albedo,

surface spectrum, and density. The last can only be determined

accurately by observing the orbits of moons the asteroid might have. So

far, every asteroid with moons has turned out to be a rubble pile, a

loose conglomeration of rock and metal that may be half empty space by

volume. The investigated asteroids are as large as 280 km in diameter,

and include

121 Hermione (268×186×183 km), and

87 Sylvia (384×262×232 km). Only half a dozen asteroids are

larger than 87 Sylvia,

though none of them have moons; however, some smaller asteroids are

thought to be more massive, suggesting they may not have been disrupted,

and indeed

511 Davida,

the same size as Sylvia to within measurement error, is estimated to be

two and a half times as massive, though this is highly uncertain. The

fact that such large asteroids as Sylvia can be rubble piles, presumably

due to disruptive impacts, has important consequences for the formation

of the Solar System: Computer simulations of collisions involving solid

bodies show them destroying each other as often as merging, but

colliding rubble piles are more likely to merge. This means that the

cores of the planets could have formed relatively quickly.

[58]

On 7 October 2009, the presence of

water ice was confirmed on the surface of

24 Themis using

NASA’s

Infrared Telescope Facility. The surface of the asteroid appears completely covered in ice. As this

ice layer is

sublimated, it may be getting replenished by a reservoir of ice under the surface. Organic compounds were also detected on the surface.

[59][60][61][62] Scientists hypothesize that some of the first water brought to

Earth was delivered by asteroid impacts after the collision that produced the

Moon. The presence of ice on 24 Themis supports this theory.

[61]

In October 2013, water was detected on an extrasolar body for the first time, on an asteroid orbiting the

white dwarf GD 61.

[63] On 22 January 2014,

European Space Agency (ESA) scientists reported the detection, for the first definitive time, of

water vapor on

Ceres, the largest object in the asteroid belt.

[64] The detection was made by using the

far-infrared abilities of the

Herschel Space Observatory.

[65]

The finding is unexpected because comets, not asteroids, are typically

considered to "sprout jets and plumes". According to one of the

scientists, "The lines are becoming more and more blurred between comets

and asteroids."

[65] In May 2016, significant asteroid data arising from the

Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer and

NEOWISE missions have been questioned,

[66][67][68] but the criticism has yet to undergo peer review.

[69]

Surface features

Most asteroids outside the "

big four" (Ceres, Pallas, Vesta, and Hygiea) are likely to be broadly similar in appearance, if irregular in shape. 50-km (31-mi)

253 Mathilde

is a rubble pile saturated with craters with diameters the size of the

asteroid's radius, and Earth-based observations of 300-km (186-mi)

511 Davida,

one of the largest asteroids after the big four, reveal a similarly

angular profile, suggesting it is also saturated with radius-size

craters.

[70] Medium-sized asteroids such as Mathilde and

243 Ida that have been observed up close also reveal a deep

regolith

covering the surface. Of the big four, Pallas and Hygiea are

practically unknown. Vesta has compression fractures encircling a

radius-size crater at its south pole but is otherwise a

spheroid.

Ceres seems quite different in the glimpses Hubble has provided, with

surface features that are unlikely to be due to simple craters and

impact basins, but details will be expanded with the

Dawn spacecraft, which entered Ceres orbit on 6 March 2015.

[71]

Color

Asteroids become darker and redder with age due to

space weathering.

[72]

However evidence suggests most of the color change occurs rapidly, in

the first hundred thousands years, limiting the usefulness of spectral

measurement for determining the age of asteroids.

[73]

Classification

Asteroids

are commonly classified according to two criteria: the characteristics

of their orbits, and features of their reflectance

spectrum.

Orbital classification

Many asteroids have been placed in groups and families based on their

orbital characteristics. Apart from the broadest divisions, it is

customary to name a group of asteroids after the first member of that

group to be discovered. Groups are relatively loose dynamical

associations, whereas families are tighter and result from the

catastrophic break-up of a large parent asteroid sometime in the past.

[74] Families have only been recognized within the

asteroid belt. They were first recognized by

Kiyotsugu Hirayama in 1918 and are often called

Hirayama families in his honor.

About 30–35% of the bodies in the asteroid belt belong to dynamical

families each thought to have a common origin in a past collision

between asteroids. A family has also been associated with the plutoid

dwarf planet Haumea.

Quasi-satellites and horseshoe objects

Some asteroids have unusual

horseshoe orbits that are co-orbital with

Earth or some other planet. Examples are

3753 Cruithne and

2002 AA29. The first instance of this type of orbital arrangement was discovered between

Saturn's moons

Epimetheus and

Janus.

Sometimes these horseshoe objects temporarily become

quasi-satellites for a few decades or a few hundred years, before returning to their earlier status. Both Earth and

Venus are known to have quasi-satellites.

Such objects, if associated with Earth or Venus or even hypothetically

Mercury, are a special class of

Aten asteroids. However, such objects could be associated with outer planets as well.

Spectral classification

This picture of

433 Eros

shows the view looking from one end of the asteroid across the gouge on

its underside and toward the opposite end. Features as small as 35 m

(115 ft) across can be seen.

In 1975, an asteroid

taxonomic system based on

color,

albedo, and

spectral shape was developed by

Clark R. Chapman,

David Morrison, and

Ben Zellner.

[75]

These properties are thought to correspond to the composition of the

asteroid's surface material. The original classification system had

three categories:

C-types for dark carbonaceous objects (75% of known asteroids),

S-types

for stony (silicaceous) objects (17% of known asteroids) and U for

those that did not fit into either C or S. This classification has since

been expanded to include many other asteroid types. The number of types

continues to grow as more asteroids are studied.

The two most widely used taxonomies now used are the

Tholen classification and

SMASS classification. The former was proposed in 1984 by

David J. Tholen,

and was based on data collected from an eight-color asteroid survey

performed in the 1980s. This resulted in 14 asteroid categories.

[76]

In 2002, the Small Main-Belt Asteroid Spectroscopic Survey resulted in a

modified version of the Tholen taxonomy with 24 different types. Both

systems have three broad categories of C, S, and X asteroids, where X

consists of mostly metallic asteroids, such as the

M-type. There are also several smaller classes.

[77]

The proportion of known asteroids falling into the various spectral

types does not necessarily reflect the proportion of all asteroids that

are of that type; some types are easier to detect than others, biasing

the totals.

Problems

Originally, spectral designations were based on inferences of an asteroid's composition.

[78]

However, the correspondence between spectral class and composition is

not always very good, and a variety of classifications are in use. This

has led to significant confusion. Although asteroids of different

spectral classifications are likely to be composed of different

materials, there are no assurances that asteroids within the same

taxonomic class are composed of similar materials.

Naming

2013 EC, shown here in radar images, has a provisional designation

A newly discovered asteroid is given a

provisional designation (such as

2002 AT4) consisting of the year of discovery and an alphanumeric code indicating the

half-month

of discovery and the sequence within that half-month. Once an

asteroid's orbit has been confirmed, it is given a number, and later may

also be given a name (e.g.

433 Eros).

The formal naming convention uses parentheses around the number (e.g.

(433) Eros), but dropping the parentheses is quite common. Informally,

it is common to drop the number altogether, or to drop it after the

first mention when a name is repeated in running text.

[79]

In addition, names can be proposed by the asteroid's discoverer, within

guidelines established by the International Astronomical Union.

[80]

Symbols

The first asteroids to be discovered were assigned iconic symbols

like the ones traditionally used to designate the planets. By 1855 there

were two dozen asteroid symbols, which often occurred in multiple

variants.

[81]

| Asteroid |

Symbol |

Year |

| 1 Ceres |

⚳    |

Ceres' scythe, reversed to double as the letter C |

1801 |

| 2 Pallas |

⚴   |

Athena's (Pallas') spear |

1801 |

| 3 Juno |

⚵    |

A star mounted on a scepter,

for Juno, the Queen of Heaven |

1804 |

| 4 Vesta |

⚶     |

The altar and sacred fire of Vesta |

1807 |

| 5 Astraea |

|

A scale, or an inverted anchor, symbols of justice |

1845 |

| 6 Hebe |

|

Hebe's cup |

1847 |

| 7 Iris |

|

A rainbow (iris) and a star |

1847 |

| 8 Flora |

|

A flower (flora), specifically the Rose of England |

1847 |

| 9 Metis |

|

The eye of wisdom and a star |

1848 |

| 10 Hygiea |

|

Hygiea's serpent and a star, or the Rod of Asclepius |

1849 |

| 11 Parthenope |

|

A harp, or a fish and a star; symbols of the sirens |

1850 |

| 12 Victoria |

|

The laurels of victory and a star |

1850 |

| 13 Egeria |

|

A shield, symbol of Egeria's protection, and a star |

1850 |

| 14 Irene |

|

A dove carrying an olive branch (symbol of

irene 'peace') with a star on its head,[82] or

an olive branch, a flag of truce, and a star |

1851 |

| 15 Eunomia |

|

A heart, symbol of good order

(eunomia), and a star |

1851 |

| 16 Psyche |

|

A butterfly's wing, symbol of

the soul (psyche), and a star |

1852 |

| 17 Thetis |

|

A dolphin, symbol of Thetis, and a star |

1852 |

| 18 Melpomene |

|

The dagger of Melpomene, and a star |

1852 |

| 19 Fortuna |

|

The wheel of fortune and a star |

1852 |

| 26 Proserpina |

|

Proserpina's pomegranate |

1853 |

| 28 Bellona |

|

Bellona's whip and lance[83] |

1854 |

| 29 Amphitrite |

|

The shell of Amphitrite and a star |

1854 |

| 35 Leukothea |

|

A lighthouse beacon, symbol of Leucothea[84] |

1855 |

| 37 Fides |

|

The cross of faith (fides)[85] |

1855 |

In 1851,

[86] after the fifteenth asteroid (

Eunomia) had been discovered,

Johann Franz Encke made a major change in the upcoming 1854 edition of the

Berliner Astronomisches Jahrbuch (BAJ,

Berlin Astronomical Yearbook).

He introduced a disk (circle), a traditional symbol for a star, as the

generic symbol for an asteroid. The circle was then numbered in order of

discovery to indicate a specific asteroid (although he assigned ① to

the fifth,

Astraea,

while continuing to designate the first four only with their existing

iconic symbols). The numbered-circle convention was quickly adopted by

astronomers, and the next asteroid to be discovered (

16 Psyche,

in 1852) was the first to be designated in that way at the time of its

discovery. However, Psyche was given an iconic symbol as well, as were a

few other asteroids discovered over the next few years (see chart

above).

20 Massalia was the first asteroid that was not assigned an iconic symbol, and no iconic symbols were created after the 1855 discovery of

37 Fides.

[87]

That year Astraea's number was increased to ⑤, but the first four

asteroids, Ceres to Vesta, were not listed by their numbers until the

1867 edition. The circle was soon abbreviated to a pair of parentheses,

which were easier to typeset and sometimes omitted altogether over the

next few decades, leading to the modern convention.

[82]

Exploration

951 Gaspra is the first asteroid to be imaged in close-up (enhanced color).

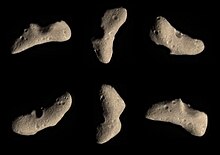

Several views of 433 Eros in natural colour

Until the age of

space travel,

objects in the asteroid belt were merely pinpricks of light in even the

largest telescopes and their shapes and terrain remained a mystery. The

best modern ground-based telescopes and the Earth-orbiting

Hubble Space Telescope

can resolve a small amount of detail on the surfaces of the largest

asteroids, but even these mostly remain little more than fuzzy blobs.

Limited information about the shapes and compositions of asteroids can

be inferred from their

light curves

(their variation in brightness as they rotate) and their spectral

properties, and asteroid sizes can be estimated by timing the lengths of

star occulations (when an asteroid passes directly in front of a star).

Radar

imaging can yield good information about asteroid shapes and orbital and

rotational parameters, especially for near-Earth asteroids. In terms of

delta-v and propellant requirements, NEOs are more easily accessible than the Moon.

[88]

The first close-up photographs of asteroid-like objects were taken in 1971, when the

Mariner 9 probe imaged

Phobos and

Deimos, the two small moons of

Mars,

which are probably captured asteroids. These images revealed the

irregular, potato-like shapes of most asteroids, as did later images

from the

Voyager probes of the small moons of the

gas giants.

The first true asteroid to be photographed in close-up was

951 Gaspra in 1991, followed in 1993 by

243 Ida and its moon

Dactyl, all of which were imaged by the

Galileo probe en route to

Jupiter.

The first dedicated asteroid probe was

NEAR Shoemaker, which photographed

253 Mathilde in 1997, before entering into orbit around

433 Eros, finally landing on its surface in 2001.

Other asteroids briefly visited by spacecraft en route to other destinations include

9969 Braille (by

Deep Space 1 in 1999), and

5535 Annefrank (by

Stardust in 2002).

In September 2005, the Japanese

Hayabusa probe started studying

25143 Itokawa in detail and was plagued with difficulties, but

returned samples of its surface to Earth on 13 June 2010.

The European

Rosetta probe (launched in 2004) flew by

2867 Šteins in 2008 and

21 Lutetia, the third-largest asteroid visited to date, in 2010.

In September 2007,

NASA launched the

Dawn spacecraft, which orbited

4 Vesta from July 2011 to September 2012, and has been orbiting the dwarf planet

1 Ceres since 2015. 4 Vesta is the second-largest asteroid visited to date.

On 13 December 2012, China's lunar orbiter

Chang'e 2 flew within 2 miles (3.2 km) of the asteroid

4179 Toutatis on an extended mission.

Planned and future missions

The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) launched the

Hayabusa 2 probe in December 2014, and plans to return samples from

162173 Ryugu in December 2020.

In May 2011, NASA selected the

OSIRIS-REx sample return mission to asteroid

101955 Bennu; it launched on September 8, 2016.

In early 2013, NASA announced the planning stages of a mission to

capture a near-Earth asteroid and move it into lunar orbit where it

could possibly be visited by astronauts and later impacted into the

Moon.

[89] On 19 June 2014, NASA reported that asteroid

2011 MD was a prime candidate for capture by a robotic mission, perhaps in the early 2020s.

[90]

It has been suggested that asteroids might be used as a source of materials that may be rare or exhausted on Earth (

asteroid mining), or materials for constructing

space habitats (see Colonization of the asteroids). Materials that are heavy and expensive to launch from Earth may someday be mined from asteroids and used for

space manufacturing and construction.

In the U.S.

Discovery program the

Psyche spacecraft proposal to

16 Psyche and

Lucy spacecraft to

Jupiter trojans made it to the semifinalist stage of mission selection.

Fiction

Asteroids and the asteroid belt are a staple of science fiction

stories. Asteroids play several potential roles in science fiction: as

places human beings might colonize, resources for extracting minerals,

hazards encountered by spacecraft traveling between two other points,

and as a threat to life on Earth or other inhabited planets, dwarf

planets and natural satellites by potential impact.

are the internal coordinates for stretching of each of the four C-H bonds.

are the internal coordinates for stretching of each of the four C-H bonds.,

, the product of the Planck constant and the vibration frequency derived using classical mechanics. For a transition from level n to level n+1 due to absorption of a photon, the frequency of the photon is equal to the classical vibration frequency

, the product of the Planck constant and the vibration frequency derived using classical mechanics. For a transition from level n to level n+1 due to absorption of a photon, the frequency of the photon is equal to the classical vibration frequency  (in the harmonic oscillator approximation).

(in the harmonic oscillator approximation).