| Zion National Park | |

|---|---|

IUCN category II (national park)

| |

Zion Canyon from Angels Landing at sunset

| |

| Location | Washington, Kane, and Iron counties, Utah, United States |

| Nearest city | Springdale (south), Orderville (east) and Cedar City near Kolob Canyons entrance |

| Coordinates | 37°18′N 113°00′WCoordinates: 37°18′N 113°00′W |

| Area | 146,597 acres (229.058 sq mi; 59,326 ha; 593.26 km2) |

| Established | November 19, 1919 |

| Visitors | 4,320,033 (in 2018) |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Official website |

Zion National Park is an American national park located in southwestern Utah near the town of Springdale. A prominent feature of the 229-square-mile (590 km2) park is Zion Canyon, which is 15 miles (24 km) long and up to 2,640 ft (800 m) deep. The canyon walls are reddish and tan-colored Navajo Sandstone eroded by the North Fork of the Virgin River. The lowest point in the park is 3,666 ft (1,117 m) at Coalpits Wash and the highest peak is 8,726 ft (2,660 m) at Horse Ranch Mountain. Located at the junction of the Colorado Plateau, Great Basin, and Mojave Desert regions, the park has a unique geography and a variety of life zones that allow for unusual plant and animal diversity. Numerous plant species as well as 289 species of birds, 75 mammals (including 19 species of bat), and 32 reptiles inhabit the park's four life zones: desert, riparian, woodland, and coniferous forest. Zion National Park includes mountains, canyons, buttes, mesas, monoliths, rivers, slot canyons, and natural arches.

Human habitation of the area started about 8,000 years ago with small family groups of Native Americans, one of which was the semi-nomadic Basketmaker Anasazi (c. 300 CE). Subsequently, the Virgin Anasazi culture (c. 500) and the Parowan Fremont group developed as the Basketmakers settled in permanent communities. Both groups moved away by 1300 and were replaced by the Parrusits and several other Southern Paiute subtribes. Mormons came into the area in 1858 and settled there in the early 1860s. In 1909, President William Howard Taft named the area Mukuntuweap National Monument in order to protect the canyon. In 1918, the acting director of the newly created National Park Service, Horace Albright, drafted a proposal to enlarge the existing monument and change the park's name to Zion National Monument, Zion being a term used by the Mormons. According to historian Hal Rothman: "The name change played to a prevalent bias of the time. Many believed that Spanish and Indian names would deter visitors who, if they could not pronounce the name of a place, might not bother to visit it. The new name, Zion, had greater appeal to an ethnocentric audience." On November 19, 1919, Congress redesignated the monument as Zion National Park, and the act was signed by President Woodrow Wilson. The Kolob section was proclaimed a separate Zion National Monument in 1937, but was incorporated into the national park in 1956.

The geology of the Zion and Kolob canyons area includes nine formations that together represent 150 million years of mostly Mesozoic-aged sedimentation. At various periods in that time warm, shallow seas, streams, ponds and lakes, vast deserts, and dry near-shore environments covered the area. Uplift associated with the creation of the Colorado Plateau lifted the region 10,000 feet (3,000 m) starting 13 million years ago.

Geography

The park is located in southwestern Utah in Washington, Iron and Kane counties. Geomorphically, it is located on the Markagunt and Kolob plateaus, at the intersection of three North American geographic provinces: the Colorado Plateau, the Great Basin, and the Mojave Desert. The northern part of the park is known as the Kolob Canyons section and is accessible from Interstate 15, exit 40.

The 8,726-foot (2,660 m) summit of Horse Ranch Mountain

is the highest point in the park; the lowest point is the 3,666-foot

(1,117 m) elevation of Coal Pits Wash, creating a relief of about 5,100

feet (1,600 m).

Streams in the area take rectangular paths because they follow jointing planes in the rocks. The stream gradient of the Virgin River,

whose North Fork flows through Zion Canyon in the park, ranges from 50

to 80 feet per mile (9.5 to 15.2 m/km) (0.9–1.5%)—one of the steepest

stream gradients in North America.

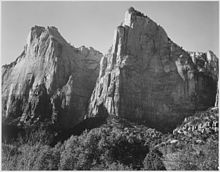

Towers of the Virgin

The road into Zion Canyon is 6 miles (9.7 km) long, ending at the Temple of Sinawava, which is named for the coyote god of the Paiute Indians. The canyon becomes more narrow near the Temple and a hiking trail continues to the mouth of The Narrows, a gorge only 20 feet (6 m) wide and up to 2,000 feet (610 m) tall.

The Zion Canyon road is served by a free shuttle bus from early April

to late October and by private vehicles the other months of the year.

Other roads in Zion are open to private vehicles year-round.

The east side of the park is served by Zion-Mount Carmel Highway (SR-9), which passes through the Zion–Mount Carmel Tunnel and ends at Mount Carmel. On the east side of the park, notable park features include Checkerboard Mesa and the East Temple.

The Kolob Terrace area, northwest of Zion Canyon, features a slot canyon called The Subway, and a panoramic view of the entire area from Lava Point. The Kolob Canyons section, further to the northwest near Cedar City, features Tucupit Point and one of the world's longest natural arches, Kolob Arch.

Court of the Patriarchs, by Ansel Adams (1933)

Other notable geographic features of Zion Canyon include Angels Landing, The Great White Throne, the Court of the Patriarchs, The West Temple, Towers of the Virgin, the Altar of Sacrifice, the Watchman, Weeping Rock, and the Emerald Pools.

Spring weather is unpredictable, with stormy, wet days being common, mixed with occasional warm, sunny weather. Precipitation is normally heaviest in March. Spring wildflowers

bloom from April through June, peaking in May. Fall days are usually

clear and mild; nights are often cool. Summer days are hot (95 to

110 °F; 35 to 43 °C), but overnight lows are usually comfortable (65 to

70 °F; 18 to 21 °C). Afternoon thunderstorms are common from mid-July through mid-September. Storms may produce waterfalls as well as flash floods.

Autumn tree-color displays begin in September in the high country; in

Zion Canyon, autumn colors usually peak in late October. Winter in Zion

Canyon is fairly mild. Winter storms bring rain or light snow to Zion

Canyon and heavier snow to the higher elevations. Clear days may become

quite warm, reaching 60 °F (16 °C); nights are often 20 to 40 °F (−7 to

4 °C).

Winter storms can last several days and make roads icy. Zion roads are

plowed, except the Kolob Terrace Road which is closed when covered with

snow. Winter driving conditions last from November through March.

Climate

Zion National Park has a BWk (Köppen climate classification)

cold desert type of climate consisting of hot summers and cold winters

with a limited amount of precipitation throughout the year.[19]

| Climate data for Zion National Park (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 73 (23) |

89 (32) |

91 (33) |

97 (36) |

106 (41) |

114 (46) |

115 (46) |

112 (44) |

110 (43) |

99 (37) |

86 (30) |

81 (27) |

115 (46) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 54.2 (12.3) |

58.3 (14.6) |

66.2 (19.0) |

74.3 (23.5) |

85.2 (29.6) |

95.7 (35.4) |

101.0 (38.3) |

98.3 (36.8) |

91.0 (32.8) |

78.3 (25.7) |

63.5 (17.5) |

53.3 (11.8) |

76.7 (24.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 42.3 (5.7) |

45.9 (7.7) |

52.3 (11.3) |

59.1 (15.1) |

68.9 (20.5) |

78.8 (26.0) |

85.0 (29.4) |

83.0 (28.3) |

75.6 (24.2) |

63.6 (17.6) |

50.3 (10.2) |

41.4 (5.2) |

62.3 (16.8) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 30.3 (−0.9) |

33.5 (0.8) |

38.3 (3.5) |

43.9 (6.6) |

52.7 (11.5) |

62.0 (16.7) |

69.0 (20.6) |

67.7 (19.8) |

60.3 (15.7) |

48.8 (9.3) |

37.0 (2.8) |

29.5 (−1.4) |

47.8 (8.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −15 (−26) |

0 (−18) |

10 (−12) |

21 (−6) |

20 (−7) |

7 (−14) |

41 (5) |

35 (2) |

33 (1) |

17 (−8) |

−10 (−23) |

−5 (−21) |

−15 (−26) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.82 (46) |

1.98 (50) |

2.04 (52) |

1.31 (33) |

0.67 (17) |

0.31 (7.9) |

1.22 (31) |

1.45 (37) |

1.04 (26) |

1.30 (33) |

1.42 (36) |

1.63 (41) |

16.19 (409.9) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.9 (2.3) |

1.0 (2.5) |

0.7 (1.8) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.5 (1.3) |

1.0 (2.5) |

4.2 (10.65) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 6.5 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 6.1 | 4.4 | 2.7 | 5.1 | 6.6 | 4.7 | 5.1 | 4.8 | 6.4 | 68 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 2.5 |

History

Archaeologists

have divided the long span of Zion's human history into three cultural

periods: the Archaic, Protohistoric and Historic periods. Each period is

characterized by distinctive technological and social adaptations.

Archaic period

The first human presence in the region dates to 8,000 years ago when family groups camped where they could hunt or collect plants and seeds. About 2,000 years ago, some groups began growing corn and other crops, leading to an increasingly sedentary lifestyle. Later groups in this period built permanent villages called pueblos. Archaeologists call this the Archaic period and it lasted until c. 500. Baskets, cordage nets, and yucca

fiber sandals have been found and dated to this period. The Archaic

toolkits included flaked stone knives, drills, and stemmed dart points.

The dart points were attached to wooden shafts and propelled by throwing

devices called atlatls.

By c. 300, some of the archaic groups developed into an early branch of seminomadic Anasazi, the Basketmakers. Basketmaker sites have grass- or stone-lined storage cists and shallow, partially underground dwellings called pithouses. They were hunters and gatherers who supplemented their diet with limited agriculture. Locally collected pine nuts were important for food and trade.

Protohistoric period

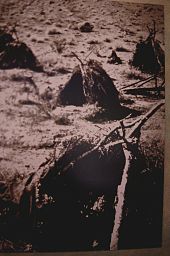

Kaun huts were used by Southern Paiute

Both the Virgin Anasazi and the Parowan Fremont disappear from the archaeological record of southwestern Utah by c. 1300.

Extended droughts in the 11th and 12th centuries, interspersed with

catastrophic flooding, may have made horticulture impossible in this

arid region.

Tradition and archaeological evidence hold that their replacements were Numic-speaking cousins of the Virgin Anasazi, such as the Southern Paiute and Ute. The newcomers migrated on a seasonal basis up and down valleys in search of wild seeds and game animals. Some, particularly the Southern Paiute, also planted fields of corn, sunflowers, and squash to supplement their diet. These more sedentary groups made brownware vessels that were used for storage and cooking.

Exploration and settlement by Euro-Americans

The Historic period begins in the late 18th century with the exploration of southern Utah by Padres Silvestre Vélez de Escalante and Francisco Atanasio Domínguez.

The padres passed near what is now the Kolob Canyons Visitor Center on

October 13, 1776, becoming the first people of European descent known to

visit the area. In 1825, trapper and trader Jedediah Smith explored some of the downstream areas while under contract with the American Fur Company.

In 1847, Mormon farmers from the Salt Lake area became the first people of European descent to settle the Virgin River region. In 1851, the Parowan and Cedar City areas were settled by Mormons who used the Kolob Canyons area for timber, and for grazing cattle, sheep, and horses. They prospected for mineral deposits, and diverted Kolob water to irrigate crops in the valley below. Mormon settlers named the area Kolob—in Mormon scripture, the heavenly place nearest the residence of God.

A ranch near the mouth of Zion Canyon (c. 1910s)

Settlements had expanded 30 miles (48 km) south to the lower Virgin River by 1858.

That year, a Southern Paiute guide led young Mormon missionary and

interpreter Nephi Johnson into the upper Virgin River area and Zion

Canyon.

Johnson wrote a favorable report about the agricultural potential of

the upper Virgin River basin, and returned later that year to found the

town of Virgin. In 1861 or 1862, Joseph Black made the arduous journey

to Zion Canyon and was very impressed by its beauty.

The floor of Zion Canyon was settled in 1863 by Isaac Behunin, who farmed corn, tobacco, and fruit trees. The Behunin family lived in Zion Canyon near the site of today's Zion Lodge

during the summer, and wintered in Springdale. Behunin is credited with

naming Zion, a reference to the place of peace mentioned in the Bible.

Two more families settled Zion Canyon in the next couple of years,

bringing with them cattle and other domesticated animals. The canyon

floor was farmed until Zion became a Monument in 1909.

The Powell Geographic Expedition of 1869 entered the area after their first trip through the Grand Canyon. John Wesley Powell visited Zion Canyon in 1872 and named it Mukuntuweap, under the impression that that was the Paiute name. Powell Survey photographers John K. Hillers and James Fennemore first visited the Zion Canyon and Kolob Plateau region in the spring of 1872. Hillers returned in April 1873 to add more photographs to the "Virgin River Series" of photographs and stereographs. Hillers described wading the canyon for four days and nearly freezing to death to take his photographs.

Protection and tourism

Painting of Zion Canyon by Frederick S. Dellenbaugh (1903)

Paintings of the canyon by Frederick S. Dellenbaugh were exhibited at the Saint Louis World's Fair in 1904, followed by a favorable article in Scribner's Magazine the next year. The article and paintings, along with previously created photographs, paintings, and reports, led to President William Howard Taft's proclamation on July 31, 1909 that created Mukuntuweap National Monument. In 1917, the acting director of the newly created National Park Service

visited the canyon and proposed changing its name from the locally

unpopular Mukuntuweap to Zion, a name used by the local Mormon

community. The United States Congress added more land and established Zion National Park on November 19, 1919.

A separate Zion National Monument, the Kolob Canyons area, was

proclaimed on January 22, 1937, and was incorporated into the park on

July 11, 1956.

Travel to the area before it was a national park was rare due to

its remote location, lack of accommodations, and the absence of real

roads in southern Utah. Old wagon roads were upgraded to the first

automobile roads starting about 1910, and the road into Zion Canyon was

built in 1917 leading to the Grotto, short of the present road that now

ends at the Temple of Sinawava.

1938 poster of Zion National Park

Touring cars could reach Zion Canyon by the summer of 1917. The first visitor lodging in Zion Canyon, called Wylie Camp, was established that same year as a tent camp. The Utah Parks Company, a subsidiary of the Union Pacific Railroad, acquired Wylie Camp in 1923, and offered ten-day rail/bus tours to Zion, nearby Bryce Canyon, the Kaibab Plateau, and the North Rim of the Grand Canyon. The Zion Lodge complex was built in 1925 at the site of the Wylie tent camp. Architect Gilbert Stanley Underwood designed the Zion Lodge in a rustic architectural style, while the Utah Parks Company funded the construction.

Infrastructure improvements

Work on the Zion Mount Carmel Highway started in 1927 to enable

reliable access between Springdale and the east side of the park. The road opened in 1930 and park visit and travel in the area greatly increased. The most famous feature of the Zion – Mount Carmel Highway is its 1.1-mile (1.8 km) tunnel, which has six large windows cut through the massive sandstone cliff.

In 1896, local rancher John Winder improved the Native American footpath up Echo Canyon, which later became the East Rim Trail.

Entrepreneur David Flanigan used this trail in 1900 to build cableworks

that lowered lumber into Zion Canyon from Cable Mountain. More than

200,000 board feet (470 m3) of lumber were lowered by 1906. The auto road was extended to the Temple of Sinawava, and a trail built from there 1 mile (1.6 km) to the start of the Narrows. Angel's Landing Trail was constructed in 1926 and two suspension bridges were built over the Virgin River. Other trails were constructed by the Civilian Conservation Corps during the 1930s.

More recent history

The Altar of Sacrifice (center) with reddish, blood-like streaks

Zion National Park has been featured in numerous films, including The Deadwood Coach (1924), Arizona Bound (1927), Nevada (1927), Ramrod (1947) and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969).

Zion Canyon Scenic Drive

provides access to Zion Canyon. Traffic congestion in the narrow canyon

was recognized as a major problem in the 1990s and a public

transportation system using propane-powered shuttle buses was instituted

in the year 2000. As part of its shuttle fleet, Zion has two electric trams each holding up to 36 passengers.

Usually from early April through late October, the scenic drive in Zion

Canyon is closed to private vehicles and visitors ride the shuttle

buses. The National Park Service has contracted the management of the shuttle bus system to transit operator RATP Dev.

Zion shuttle bus stops are marked with numbers

On April 12, 1995, heavy rains triggered a landslide that blocked the Virgin River in Zion Canyon.

Over a period of two hours, the river carved away part of the only

exit road from the canyon, trapping 450 guests and employees at the Zion

Lodge. A one-lane, temporary road was constructed within 24 hours to allow evacuation of the Lodge. A more stable — albeit temporary — road was completed on May 25, 1995 to allow summer visitors to access the canyon. This road was replaced with a permanent road during the first half of 1996.

The Zion–Mount Carmel Highway can be travelled year-round. Access

for oversized vehicles requires a special permit, and is limited to

daytime hours, as traffic through the tunnel must be one way to

accommodate large vehicles. The 5-mile (8.0 km)-long Kolob Canyons Road

was built to provide access to the Kolob Canyons section of the park. This road often closes in the winter.

In March 2009, President Barack Obama signed into law the Omnibus Public Land Management Act of 2009, which designated and further protected 124,406 acres (50,345 ha) of park land as the Zion Wilderness.

In September 2015, flooding trapped a party of seven in Keyhole Canyon, a slot canyon in the park. The flash flood killed all seven members of the group, whose remains were located after a search lasting several days.

On March 25, 2020, the park campgrounds were closed to help prevent the spread of COVID-19.

Geology

The Three Patriarchs in Zion Canyon are made of Navajo Sandstone

The nine known exposed geologic formations in Zion National Park are part of a super-sequence of rock units called the Grand Staircase. Together, these formations represent about 150 million years of mostly Mesozoic-aged sedimentation in that part of North America. The formations exposed in the Zion area were deposited as sediment in very different environments:

- The warm, shallow (sometimes advancing or retreating) sea of the Kaibab and Moenkopi formations;

- Streams, ponds, and lakes of the Chinle, Moenave, and Kayenta formations;

- The vast desert of the Navajo and Temple Cap formations; and

- The dry near-shore environment of the Carmel Formation.

The Kolob Canyons are a set of finger canyons cut into the Kolob Plateau

Uplift affected the entire region, known as the Colorado Plateaus, by slowly raising these formations more than 10,000 feet (3,000 m) higher than where they were deposited. This steepened the stream gradient of the ancestral Virgin and other rivers on the plateau.

The faster-moving streams took advantage of uplift-created joints in the rocks. Eventually, all Cenozoic-aged

formations were removed and gorges were cut into the plateaus. Zion

Canyon was cut by the North Fork of the Virgin River in this way. During

the later part of this process, lava flows and cinder cones covered parts of the area.

High water volume in wet seasons does most of the downcutting in the main canyon. These flood events are responsible for transporting most of the 3 million short tons (2.7 million metric tons) of rock and sediment that the Virgin River transports yearly. The Virgin cuts away its canyon faster than its tributaries can cut away their own streambeds, so tributaries end in waterfalls from hanging valleys where they meet the Virgin. The valley between the peaks of the Twin Brothers is a notable example of a hanging valley in the canyon.

| Rock layer | Appearance | Location | Deposition | Rock type | Photo |

| Dakota Formation | Cliffs | Top of Horse Ranch Mountain | Streams | Conglomerate and sandstone |

|

| Carmel Formation | Cliffs | Mount Carmel Junction | Shallow sea and coastal desert | Limestone, sandstone and gypsum | |

| Temple Cap Formation | Cliffs | Top of West Temple | Desert | Sandstone |

|

| Navajo Sandstone | Steep cliffs 1,600 to 2,200 ft (490 to 670 m) thick; red lower layers are colored by iron oxides | Tall cliffs of Zion Canyon; highest exposure is West Temple; cross-bedding shows well at Checkerboard Mesa (photo) | Sand dunes covered 150,000 sq mi (390,000 km2); shifting winds during deposition created cross-bedding | Sandstone |

|

| Kayenta Formation | Rocky slopes | Throughout canyon | Streams | Siltstone and sandstone |

|

| Moenave Formation | Slopes and ledges | Lower red cliffs seen from Zion Human History Museum | Streams and ponds | Siltstone and sandstone | |

| Chinle Formation | Purplish slopes | Above Rockville | Streams | Shale, loose clay and conglomerate | |

| Moenkopi Formation | Chocolate cliffs with white bands | Rocky slopes from Virgin to Rockville | Shallow sea | Shale, siltstone, sandstone, mudstone, and limestone | |

| Kaibab Limestone | Cliffs | Hurricane Cliffs along I-15 near Kolob Canyons | Shallow sea | Limestone |

Biology

Taylor Creek with Horse Ranch Mountain in background. Desert, riparian, woodland, and coniferous forest habitats are all visible.

The Great Basin, Mojave Desert, and Colorado Plateau converge at Zion and the Kolob canyons. This, along with the varied topography of canyon–mesa country, differing soil types, and uneven water availability, provides diverse habitat for the equally diverse mix of plants and animals that live in the area. The park is home to 289 bird, 79 mammals, 28 reptiles, 7 fish, and 6 amphibian species. These organisms make their homes in one or more of four life zones found in the Park: desert, riparian, woodland, and coniferous forest.

Desert conditions persist on canyon bottoms and rocky ledges away from perennial streams. Sagebrush, prickly pear cactus, and rabbitbrush, along with sacred datura and Indian paintbrush, are common. Utah penstemon and golden aster can also be found. Milkvetch and prince's plume are found in pockets of selenium-rich soils.

Common daytime animals include mule deer, rock squirrels, pinyon jays, and whiptail and collared lizards. Desert cottontails, jackrabbits, and Merriam's kangaroo rats come out at night. Cougars, bobcats, coyotes, badgers, gray foxes, and ring-tail cats are the top predators.

Cooler conditions persist at mid-elevation slopes, from 3,900 to 5,500 feet (1,200 to 1,700 m). Stunted forests of pinyon pine and juniper coexist here with manzanita shrubs, cliffrose, serviceberry, scrub oak, and yucca. Stands of ponderosa pine, Gambel oak, manzanita and aspen populate the mesas and cliffs above 6,000 feet (1,800 m).

Desert bighorn sheep are often visible near the roadway in the park.

Golden eagles, red-tailed hawks, peregrine falcons, and white-throated swifts can be seen in the area. Desert bighorn sheep were reintroduced in the park in 1973. California condors were reintroduced in the Arizona Strip and in 2014 the first successful breeding of condors in the park was confirmed.[56] Nineteen species of bat also live in the area.

Boxelder, Fremont cottonwood, maple, and willow dominate riparian plant communities. Animals such as bank beavers, flannel-mouth suckers, gnatcatchers, dippers, canyon wrens, the virgin spinedace, and water striders all make their homes in the riparian zones.

Activities

Guided horseback riding trips, nature walks, and evening programs are available from late March to early November. The Junior Ranger Program for ages 6–12 is active from Memorial Day to Labor Day at the Zion Nature Center.

Rangers at the visitor centers in Zion Canyon and Kolob Canyons can

help visitors plan their stay. A bookstore attached to the Zion Canyon

visitor center offers books, maps, and souvenirs. The Grotto in Zion Canyon, the visitor center, and the viewpoint at the end of Kolob Canyons Road have the only designated picnic sites.

The Subway, a slot canyon within the Kolob Terrace section

- Trails

Seven trails with round-trip times of half an hour (Weeping Rock) to 4 hours (Angels Landing) are found in Zion Canyon. Two popular trails, Taylor Creek (4 hours round trip) and Kolob Arch (8 hours round trip), are in the Kolob Canyons section of the park, near Cedar City. Hiking up into The Narrows

from the Temple of Sinawava is popular in summer; however, hiking

beyond Big Springs requires a permit. The entire Narrows from

Chamberlain's Ranch is a 16-mile one way trip that typically takes 12

hours of strenuous hiking.

A shorter alternative is to enter the Narrows via Orderville Canyon.

Both Orderville and the full Narrows require a back country permit.

Entrance to the Parunuweap Canyon section of the park downstream of

Labyrinth Falls is prohibited. Other often-used backcountry trails

include the West Rim and LaVerkin Creek. The more primitive sections of Zion include the Kolob Terrace and the Kolob Canyons.

A network of trails totaling 50 miles in distance connect Zion's

northwest corner of the park (Lee Pass Trailhead) to its southeast

section (East Rim Trailhead). Popularly known as the Zion Traverse, the

route offers backpackers a diverse experience of the park.

Zion is a center for rock climbing,

with short walls like Spaceshot, Moonlight Buttress, Prodigal Son,

Ashtar Command, and Touchstone being the most popular, highly rated

routes.

- Camping and lodging

Zion Lodge accommodations

Lodging in the park is available at Zion Lodge, located halfway through Zion Canyon. Three campgrounds

are available: South and Watchman at the far southern side of the park,

and a primitive site at Lava Point in the middle of the park off Kolob

Terrace Road. Overnight camping in the backcountry requires permits.