Antinatalism, or anti-natalism, is a philosophical position that assigns a negative value to birth. Antinatalists argue that humans should abstain from procreation because it is morally wrong (some also recognize the procreation of other sentient beings as morally wrong). In scholarly and in literary writings, various ethical foundations have been presented for antinatalism. Some of the earliest surviving formulations of the idea that it would be better not to have been born come from ancient Greece. The term antinatalism is in opposition to the term natalism or pro-natalism, and was used probably for the first time as the name of the position by Théophile de Giraud in his book L'art de guillotiner les procréateurs: Manifeste anti-nataliste.

Arguments

In religion

The teaching of the Buddha, among other Four Noble Truths and the beginning of Mahāvagga, is interpreted by Hari Singh Gour as follows:

Buddha states his propositions in the pedantic style of his age. He throws them into a form of sorites; but, as such, it is logically faulty and all he wishes to convey is this: Oblivious of the suffering to which life is subject, man begets children, and is thus the cause of old age and death. If he would only realize what suffering he would add to by his act, he would desist from the procreation of children; and so stop the operation of old age and death.

The Marcionites believed that the visible world is an evil creation of a crude, cruel, jealous, angry demiurge, Yahweh. According to this teaching, people should oppose him, abandon his world, not create people, and trust in the good God of mercy, foreign and distant.

The Encratites observed that birth leads to death. In order to conquer death, people should desist from procreation: "not produce fresh fodder for death".

The Manichaeans, the Bogomils and the Cathars believed that procreation sentences the soul to imprisonment in evil matter. They saw procreation as an instrument of an evil god, demiurge, or of Satan that imprisons the divine element in the matter and thus causes the divine element to suffer.

Theodicy and anthropodicy

Julio Cabrera considers the issue of being a creator in relation to theodicy and argues that just as it is impossible to defend the idea of a good God as creator, it is also impossible to defend the idea of a good man as a creator. In parenthood, the human parent imitates the divine parent, in the sense that education could be understood as a form of pursuit of "salvation", the "right path" for a child. However, a human being could decide that it is better not to suffer at all than to suffer and be offered the later possibility of salvation from suffering. In Cabrera's opinion, evil is associated not with the lack of being, but with the suffering and dying of those that are alive. So, on the contrary, evil is only and obviously associated with being.

Karim Akerma, due to the moral problem of man as creator, introduces anthropodicy, a twin concept for theodicy. He is of the opinion that the less faith in the Almighty Creator-God there is, the more urgent the question of anthropodicy becomes. Akerma thinks that for those who want to lead ethical lives, the causation of suffering requires a justification. Man can no longer shed responsibility for the suffering that occurs by appealing to an imaginary entity that sets moral principles. For Akerma, antinatalism is a consequence of the collapse of theodicy endeavors and the failure of attempts to establish an anthropodicy. According to him, there is no metaphysics nor moral theory that can justify the production of new people, and therefore anthropodicy is indefensible as well as theodicy.

Peter Wessel Zapffe

Peter Wessel Zapffe viewed humans as a biological paradox. According to him, consciousness has become over-evolved in humans, thereby making us incapable of functioning normally like other animals: cognition gives us more than we can carry. Our frailness and insignificance in the cosmos are visible to us. We want to live, and yet because of how we have evolved, we are the only species whose members are conscious that they are destined to die. We are able to analyze the past and the future, both our situation and that of others, as well as to imagine the suffering of billions of people (as well as of other living beings) and feel compassion for their suffering. We yearn for justice and meaning in a world that lacks both. This ensures that the lives of conscious individuals are tragic. We have desires: spiritual needs that reality is unable to satisfy, and our species still exists only because we limit our awareness of what that reality actually entails. Human existence amounts to a tangled network of defense mechanisms, which can be observed both individually and socially, in our everyday behavior patterns. According to Zapffe, humanity should cease this self-deception, and the natural consequence would be its extinction by abstaining from procreation.

Negative ethics

Julio Cabrera proposes a concept of "negative ethics" in opposition to "affirmative" ethics, meaning ethics that affirm being. He describes procreation as manipulation and harm, a unilateral and non-consensual sending of a human being into a painful, dangerous and morally impeding situation.

Cabrera regards procreation as an ontological issue of total manipulation: one's very being is manufactured and used; in contrast to intra-worldly cases where someone is placed in a harmful situation. In the case of procreation, no chance of defense against that act is even available. According to Cabrera: manipulation in procreation is visible primarily in the unilateral and non-consensual nature of the act, which makes procreation per se inevitably asymmetrical; be it a product of forethought, or a product of neglect. It is always connected with the interests (or disinterests) of other humans, not the created human. In addition, Cabrera points out that in his view the manipulation of procreation is not limited to the act of creation itself, but it is continued in the process of raising the child, during which parents gain great power over the child's life, who is shaped according to their preferences and for their satisfaction. He emphasizes that although it is not possible to avoid manipulation in procreation, it is perfectly possible to avoid procreation itself and that then no moral rule is violated.

Cabrera believes that the situation in which one is placed through procreation, human life, is structurally negative in that its constitutive features are inherently adverse. The most prominent of them are, according to Cabrera, the following:

- The being acquired by a human at birth is decreasing (or "decaying"), in the sense of a being that begins to end since its very emergence, following a single and irreversible direction of deterioration and decline, of which complete consummation can occur at any moment between some minutes and around one hundred years.

- From the moment they come into being, humans are affected by three kinds of frictions: physical pain (in the form of illnesses, accidents, and natural catastrophes to which they are always exposed); discouragement (in the form of "lacking the will", or the "mood" or the "spirit", to continue to act, from mild taedium vitae to serious forms of depression), and finally, exposure to the aggressions of other humans (from gossip and slander to various forms of discrimination, persecution, and injustice), aggressions that we too can inflict on others, also submitted, like us, to the three kinds of friction.

- To defend themselves against (a) and (b), human beings are equipped with mechanisms of creation of positive values (ethical, aesthetic, religious, entertaining, recreational, as well as values contained in human realizations of all kinds), which humans must keep constantly active. All positive values that appear within human life are reactive and palliative; they are introduced by the permanent, anxious, and uncertain struggle against the decaying life and its three kinds of friction.

Cabrera calls the set of these characteristics A–C the "terminality of being". He is of the opinion that a huge number of humans around the world cannot withstand this steep struggle against the terminal structure of their being, which leads to destructive consequences for them and others: suicides, major or minor mental illnesses, or aggressive behavior. He accepts that life may be – thanks to human's own merits and efforts – bearable and even very pleasant (though not for all, due to the phenomenon of moral impediment), but also considers it problematic to bring someone into existence so that they may attempt to make their life pleasant by struggling against the difficult and oppressive situation we place them in by procreating. It seems more reasonable, according to Cabrera, simply not to put them in that situation, since the results of their struggle are always uncertain.

Cabrera believes that in ethics, including affirmative ethics, there is one overarching concept which he calls the "Minimal Ethical Articulation", "MEA" (previously translated into English as "Fundamental Ethical Articulation" and "FEA"): the consideration of other people's interests, not manipulating them and not harming them. Procreation for him is an obvious violation of MEA – someone is manipulated and placed in a harmful situation as a result of that action. In his view, values included in the MEA are widely accepted by affirmative ethics, they are even their basics, and if approached radically, they should lead to the refusal of procreation.

For Cabrera, the worst thing in human life and by extension in procreation is what he calls "moral impediment": the structural impossibility of acting in the world without harming or manipulating someone at some given moment. This impediment does not occur because of an intrinsic "evil" of human nature, but because of the structural situation in which the human being has always been. In this situation, we are cornered by various kinds of pain, space for action is limited, and different interests often conflict with each other. We do not have to have bad intentions to treat others with disregard; we are compelled to do so in order to survive, pursue our projects, and escape from suffering. Cabrera also draws attention to the fact that life is associated with the constant risk of one experiencing strong physical pain, which is common in human life, for example as a result of a serious illness, and maintains that the mere existence of such possibility impedes us morally, as well as that because of it, we can at any time lose, as a result of its occurrence, the possibility of a dignified, moral functioning even to a minimal extent.

Kantian imperative

Julio Cabrera, David Benatar and Karim Akerma all argue that procreation is contrary to Immanuel Kant's practical imperative (according to Kant, a man should never be used as merely a means to an end, but always be treated as an end in himself). They argue that a person can be created for the sake of his parents or other people, but that it is impossible to create someone for his own good; and that therefore, following Kant's recommendation, we should not create new people. Heiko Puls argues that Kant's considerations regarding parental duties and human procreation, in general, imply arguments for an ethically justified antinatalism. Kant, however, according to Puls, rejects this position in his teleology for meta-ethical reasons.

Impossibility of consent

Seana Shiffrin, Gerald Harrison, Julia Tanner and Asheel Singh argue that procreation is morally problematic because of the impossibility of obtaining consent from the human who will be brought into existence.

Shiffrin lists four factors that in her opinion make the justification for having hypothetical consent to procreation a problem:

- great harm is not at stake if the action is not taken;

- if the action is taken, the harms suffered by the created person can be very severe;

- a person cannot escape the imposed condition without very high cost (suicide is often a physically, emotionally, and morally excruciating option);

- the hypothetical consent procedure is not based on the values of the person who will bear the imposed condition.

Gerald Harrison and Julia Tanner argue that when we want to significantly affect someone by our action and it is not possible to get their consent, then the default should be to not take such action. The exception is, according to them, actions by which we want to prevent greater harm of a person (for example, pushing someone out of the way of a falling piano). However, in their opinion, such actions certainly do not include procreation, because before taking this action a person does not exist.

Asheel Singh emphasizes that one does not have to think that coming into existence is always an overall harm in order to recognize antinatalism as a correct view. In his opinion, it is enough to think that there is no moral right to inflict serious, preventable harms upon others without their consent.

Death as a harm

Marc Larock presents a view which he calls "deprivationalism". According to this view:

- Each person has an interest in acquiring a new satisfied preference.

- Whenever a person is deprived of a new satisfied preference this violates an interest and thus causes harm.

Larock argues that if a person is deprived of an infinite number of new satisfied preferences, they suffer an infinite number of harms and that such deprivation is death to which procreation leads.

All of us are brought into existence, without our consent, and over the course of our lives, we are acquainted with a multitude of goods. Unfortunately, there is a limit to the amount of good each of us will have in our lives. Eventually, each of us will die and we will be permanently cut off from the prospect of any further good. Existence, viewed in this way, seems to be a cruel joke.

Larock believes that it is not correct to neutralize his view by stating that death is also an infinitely great benefit for us, because it protects us from the infinite number of new frustrated preferences. He proposes a thought experiment in which we have two people, Mary and Tom. The first person, Mary, dies at the age of forty years as a result of complications caused by a degenerative disease. Mary would live for some more time, if not for the complications, but she would only experience bad things in her life, not good ones. The second person, Tom, dies at the same age from the same illness, but in his case, the disease is at such a stage of development that his body would no longer be able to function. According to Larock, it is bad when someone, like in the case of Tom, encounters the impossibility of continuing to derive good things from his life; everybody's life leads to such a point if someone lives long enough and our intuitions do not tell us that this is generally good or even neutral. Therefore, we should reject the view that death is also an infinitely great benefit: because we think that Tom has been unlucky. In the case of Mary, our intuitions tell us that her misfortune is not as great as Tom's misfortune. Her misfortune is reduced by the fact that death saved her from the real prospect of experiencing bad things. We do not have the same intuition in Tom's case. No evil or good future was physically possible for him. Larock thinks that while the impossibility of experiencing future good things seems to us to be a harm, the mere lack of a logical possibility of experiencing future bad things does not seem to be a compensatory benefit to us. If so, there would be nothing strange in recognizing that Tom had not suffered any misfortune. But he is a victim of misfortune, just like Mary. However, Mary's misfortune does not seem to be so great because her death prevents great suffering. Larock is of the opinion that most people will see both cases in this way. This conclusion is supposed to lead to the fact that we recognize that there is an asymmetry between the harms and benefits that death brings.

Larock summarizes his view as follows:

The existence of every moral patient in our world rests on a crude moral miscalculation. As I see it, non-procreation is the best means of rectifying this mistake.

Negative utilitarianism

Negative utilitarianism argues that minimizing suffering has greater moral importance than maximizing happiness.

Hermann Vetter agrees with the assumptions of Jan Narveson:

- There is no moral obligation to produce a child even if we could be sure that it will be very happy throughout its life.

- There is a moral obligation not to produce a child if it can be foreseen that it will be unhappy.

However, he disagrees with the conclusion that Narveson draws:

- In general – if it can be foreseen neither that the child will be unhappy nor that it will bring disutility upon others – there is no duty to have or not to have a child.

Instead, he presents the following decision-theoretic matrix:

| Child will be more or less happy | Child will be more or less unhappy | |

|---|---|---|

| Produce the child | No duty fulfilled or violated | Duty violated |

| Do not produce the child | No duty fulfilled or violated | Duty fulfilled |

Based on this, he concludes that we should not create people:

It is seen immediately that the act "do not produce the child" dominates the act "produce the child" because it has equally good consequences as the other act in one case and better consequences in the other. So it is to be preferred to the other act as long as we cannot exclude with certainty the possibility that the child will be more or less unhappy; and we never can. So we have, instead of (3), the far-reaching consequence: (3') In any case, it is morally preferable not to produce a child.

Karim Akerma argues that utilitarianism requires the least metaphysical assumptions and is, therefore, the most convincing ethical theory. He believes that negative utilitarianism is the right one because the good things in life do not compensate for the bad things; first and foremost, the best things do not compensate for the worst things such as, for example, the experiences of terrible pain, the agonies of the wounded, sick or dying. In his opinion, we also rarely know what to do to make people happy, but we know what to do so that people do not suffer: it is enough that they are not created. What is important for Akerma in ethics is the striving for the fewest suffering people (ultimately no one), not striving for the happiest people, which, according to him, takes place at the expense of immeasurable suffering.

Bruno Contestabile cites the story "The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas" by Ursula K. Le Guin. In this story, the existence of the utopian city of Omelas and the good fortune of its inhabitants depend on the suffering of one child who is tortured in an isolated place and who cannot be helped. The majority accepts this state of affairs and stays in the city, but there are those who do not agree with it, who do not want to participate in it and thus they "walk away from Omelas". Contestabile draws a parallel here: for Omelas to exist, the child must be tortured, and in the same way, the existence of our world is related to the fact that someone is constantly harmed. According to Contestabile, antinatalists can be seen just as "the ones who walk away from Omelas", who do not accept such a world, and who do not approve of its perpetuation. He poses the question: is all happiness able to compensate for the extreme suffering of even one person?

David Benatar

Asymmetry between pleasure and pain

David Benatar argues that there is a crucial asymmetry between the good and the bad things, such as pleasure and pain:

- the presence of pain is bad;

- the presence of pleasure is good;

- the absence of pain is good, even if that good is not enjoyed by anyone;

- the absence of pleasure is not bad unless there is somebody for whom this absence is a deprivation.

| Scenario A (X exists) | Scenario B (X never exists) |

|---|---|

| 1. Presence of pain (Bad) | 3. Absence of pain (Good) |

| 2. Presence of pleasure (Good) | 4. Absence of pleasure (Not bad) |

Regarding procreation, the argument follows that coming into existence generates both good and bad experiences, pain and pleasure, whereas not coming into existence entails neither pain nor pleasure. The absence of pain is good, the absence of pleasure is not bad. Therefore, the ethical choice is weighed in favor of non-procreation.

Benatar explains the above asymmetry using four other asymmetries that he considers quite plausible:

- We have a moral obligation not to create unhappy people and we have no moral obligation to create happy people. The reason why we think there is a moral obligation not to create unhappy people is that the presence of this suffering would be bad (for the sufferers) and the absence of the suffering is good (even though there is nobody to enjoy the absence of suffering). By contrast, the reason we think there is no moral obligation to create happy people is that although their pleasure would be good for them, the absence of pleasure when they do not come into existence will not be bad, because there will be no one who will be deprived of this good.

- It is strange to mention the interests of a potential child as a reason why we decide to create them, and it is not strange to mention the interests of a potential child as a reason why we decide not to create them. That the child may be happy is not a morally important reason to create them. By contrast, that the child may be unhappy is an important moral reason not to create them. If it were the case that the absence of pleasure is bad even if someone does not exist to experience its absence, then we would have a significant moral reason to create a child and to create as many children as possible. And if it were not the case that the absence of pain is good even if someone does not exist to experience this good, then we would not have a significant moral reason not to create a child.

- Someday we can regret for the sake of a person whose existence was conditional on our decision, that we created them – a person can be unhappy and the presence of their pain would be a bad thing. But we will never feel regret for the sake of a person whose existence was conditional on our decision, that we did not create them – a person will not be deprived of happiness, because he or she will never exist, and the absence of happiness will not be bad, because there will be no one who will be deprived of this good.

- We feel sadness by the fact that somewhere people come into existence and suffer, and we feel no sadness by the fact that somewhere people did not come into existence in a place where there are happy people. When we know that somewhere people came into existence and suffer, we feel compassion. The fact that on some deserted island or planet people did not come into existence and suffer is good. This is because the absence of pain is good even when there is not someone who is experiencing this good. On the other hand, we do not feel sadness by the fact that on some deserted island or planet people did not come into existence and are not happy. This is because the absence of pleasure is bad only when someone exists to be deprived of this good.

Suffering experienced by descendents

According to Benatar, by creating a child, we are responsible not only for this child's suffering, but we may also be co-responsible for the suffering of further offspring of this child.

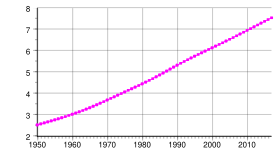

Assuming that each couple has three children, an original pair's cumulative descendants over ten generations amount to 88,572 people. That constitutes a lot of pointless, avoidable suffering. To be sure, full responsibility for it all does not lie with the original couple because each new generation faces the choice of whether to continue that line of descendants. Nevertheless, they bear some responsibility for the generations that ensue. If one does not desist from having children, one can hardly expect one's descendants to do so.

Consequences of procreation

Benatar cites statistics showing where the creation of people leads. It is estimated that:

- more than fifteen million people are thought to have died from natural disasters in the last 1,000 years,

- approximately 20,000 people die every day from hunger,

- an estimated 840 million people suffer from hunger and malnutrition,

- between 541 and 1912, it is estimated that over 102 million people succumbed to plague,

- the 1918 influenza epidemic killed 50 million people,

- nearly 11 million people die every year from infectious diseases,

- malignant neoplasms take more than a further 7 million lives each year,

- approximately 3.5 million people die every year in accidents,

- approximately 56.5 million people died in 2001, that is more than 107 people per minute,

- before the twentieth century over 133 million people were killed in mass killings,

- in the first 88 years of the twentieth century 170 million (and possibly as many as 360 million) people were shot, beaten, tortured, knifed, burned, starved, frozen, crushed, or worked to death; buried alive, drowned, hanged, bombed, or killed in any other of the myriad ways governments have inflicted death on unarmed, helpless citizens and foreigners,

- there were 1.6 million conflict-related deaths in the sixteenth century, 6.1 million in the seventeenth century, 7 million in the eighteenth, 19.4 million in the nineteenth, and 109.7 million in the twentieth,

- war-related injuries led to 310,000 deaths in 2000,

- about 40 million children are maltreated each year,

- more than 100 million currently living women and girls have been subjected to genital cutting,

- 815,000 people are thought to have committed suicide in 2000[50] (currently, it is estimated that someone commits suicide every 40 seconds, more than 800,000 people per year).[51]

Misanthropy

In addition to the philanthropic arguments, which are based on a concern for the humans who will be brought into existence, Benatar also posits that another path to antinatalism is the misanthropic argument that can be summarized in his opinion as follows:

Another route to anti-natalism is via what I call a "misanthropic" argument. According to this argument, humans are a deeply flawed and destructive species that is responsible for the suffering and deaths of billions of other humans and non-human animals. If that level of destruction were caused by another species we would rapidly recommend that new members of that species not be brought into existence.

Harm to non-human animals

David Benatar, Gunter Bleibohm, Gerald Harrison, Julia Tanner, and Patricia MacCormack are attentive to the harm caused to other sentient beings by humans. They would say that billions of non-human animals are abused and slaughtered each year by our species for the production of animal products, for experimentation and after the experiments (when they are no longer needed), as a result of the destruction of habitats or other environmental damage and for sadistic pleasure. They tend to agree with animal rights thinkers that the harm we do to them is immoral. They consider the human species the most destructive on the planet, arguing that without new humans, there will be no harm caused to other sentient beings by new humans.

Some antinatalists are also vegetarians or vegans for moral reasons, and postulate that such views should complement each other as having a common denominator: not causing harm to other sentient beings. This attitude was already present in Manichaeism and Catharism.

Environmental impact

Volunteers of the Voluntary Human Extinction Movement argue that human activity is the primary cause of environmental degradation, and therefore refraining from reproduction is "the humanitarian alternative to human disasters". Others, in the United States and other developed countries, are similarly concerned about contributing to climate change and other environmental problems by having biological children.

Realism

Some antinatalists believe that most people do not evaluate reality accurately, which affects the desire to have children.

Peter Wessel Zapffe identifies four repressive mechanisms we use, consciously or not, to restrict our consciousness of life and the world:

- isolation – an arbitrary dismissal from our consciousness and the consciousness of others about all negative thoughts and feelings associated with the unpleasant facts of our existence. In daily life, this manifests as a tacit agreement to remain silent on certain subjects – especially around children, to prevent instilling in them a fear of the world and what awaits them in life, before they will be able to learn other mechanisms.

- anchoring – the creation and use of personal values to ensure our attachment to reality, such as parents, home, the street, school, God, the church, the State, morality, fate, the law of life, the people, the future, accumulation of material goods or authority, etc. This can be characterized as creating a defensive structure, "a fixation of points within, or construction of walls around, the liquid fray of consciousness", and defending the structure against threats.

- distraction – shifting focus to new impressions to flee from circumstances and ideas we consider harmful or unpleasant.

- sublimation – refocusing the tragic parts of life into something creative or valuable, usually through an aesthetic confrontation for the purpose of catharsis. We focus on the imaginary, dramatic, heroic, lyric or comic aspects of life, to allow ourselves and others an escape from their true impact.

According to Zapffe, depressive disorders are often "messages from a deeper, more immediate sense of life, bitter fruits of a geniality of thought". Some studies seem to confirm this, it is said about the phenomenon of depressive realism, and Colin Feltham writes about antinatalism as one of its possible consequences.

David Benatar citing numerous studies lists three phenomena described by psychologists, which, according to him, are responsible for making our self-assessments about the quality of our lives unreliable:

- Tendency towards optimism (or Pollyanna principle) – we have a positively distorted picture of our lives in the past, present and future.

- Adaptation (or accommodation, habituation) – we adapt to negative situations and adjust our expectations accordingly.

- Comparison – for our self-assessments about the quality of our lives, more important than how our lives go is how they go in comparison with the lives of others. One of the effects of this is that negative aspects of life that affect everyone are not taken into account when assessing our own well-being. We are also more likely to compare ourselves with those who are worse off than those who are better off.

Benatar concludes:

The above psychological phenomena are unsurprising from an evolutionary perspective. They militate against suicide and in favour of reproduction. If our lives are quite as bad as I shall still suggest they are, and if people were prone to see this true quality of their lives for what it is, they might be much more inclined to kill themselves, or at least not to produce more such lives. Pessimism, then, tends not to be naturally selected.

Thomas Ligotti draws attention to the similarity between Zapffe's philosophy and terror management theory. Terror management theory argues that humans are equipped with unique cognitive abilities beyond what is necessary for survival, which includes symbolic thinking, extensive self-consciousness and perception of themselves as temporal beings aware of the finitude of their existence. The desire to live alongside our awareness of the inevitability of death triggers terror in us. Opposition to this fear is among our primary motivations. To escape it, we build defensive structures around ourselves to ensure our symbolic or literal immortality, to feel like valuable members of a meaningful universe, and to focus on protecting ourselves from immediate external threats.

Practical implications

Abortion

Antinatalism can lead to a particular position on the morality of abortion.

According to David Benatar, one comes into existence in the morally relevant sense when consciousness arises, when a fetus becomes sentient, and up until that time an abortion is moral, whereas continued pregnancy would be immoral. Benatar refers to EEG brain studies and studies on the pain perception of the fetus, which states that fetal consciousness arises no earlier than between twenty-eight and thirty weeks of pregnancy, before which it is incapable of feeling pain. Contrary to that, the latest report from the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists showed that the fetus gains consciousness no earlier than week twenty-four of the pregnancy. Some assumptions of this report regarding sentience of the fetus after the second trimester were criticized. In a similar way argues Karim Akerma. He distinguishes between organisms that do not have mental properties and living beings that have mental properties. According to his view, which he calls the mentalistic view, a living being begins to exist when an organism (or another entity) produces a simple form of consciousness for the first time.

Julio Cabrera believes that the moral problem of abortion is totally different from the problem of abstention of procreation because in the case of abortion, there is no longer a non-being, but an already existing being – the most helpless and defenseless of the parties involved, that someday will have the autonomy to decide, and we cannot decide for them. From the point of view of Cabrera's negative ethics, abortion is immoral for similar reasons as procreation. For Cabrera, the exception in which abortion is morally justified is cases of irreversible illness of the foetus (or some serious "social illnesses" like American conquest or Nazism), according to him in such cases we are clearly thinking about the unborn, and not simply of our own interests. In addition, Cabrera believes that under certain circumstances, it is legitimate and comprehensible to commit unethical actions, for example, abortion is legitimate and comprehensible when the mother's life is at risk.

Adoption

Herman Vetter, Théophile de Giraud, Travis N. Rieder, Tina Rulli, Karim Akerma and Julio Cabrera argue that presently rather than engaging in the morally problematic act of procreation, one could do good by adopting already existing children. De Giraud emphasizes that, across the world, there are millions of existing children who need care.

Famine relief

Stuart Rachels and David Benatar argue that presently, in a situation where a huge number of people live in poverty, we should cease procreation and divert these resources, that would have been used to raise our own children, to the poor.

Non-human animals

Some antinatalists recognize the procreation of non-human sentient animals as morally bad, and some view sterilization as morally good in their case. Karim Akerma defines antinatalism, that includes non-human sentient animals, as universal antinatalism and he assumes such a position himself:

By sterilising animals, we can free them from being slaves to their instincts and from bringing more and more captive animals into the cycle of being born, contracting parasites, ageing, falling ill and dying; eating and being eaten.

David Benatar emphasizes that his asymmetry applies to all sentient beings, and mentions that humans play a role in deciding how many animals there will be: humans breed many species of animals.

Magnus Vinding argues that the lives of wild animals in their natural environment are generally very bad. He draws attention to phenomena such as dying before adulthood, starvation, disease, parasitism, infanticide, predation and being eaten alive. He cites research on what animal life looks like in the wild. One of eight male lion cubs survives into adulthood. Others die as a result of starvation, disease and often fall victims to the teeth and claws of other lions. Attaining adulthood is much rarer for fish. Only one in a hundred male chinook salmon survives into adulthood. Vinding is of the opinion that if human lives and the survival of human children looked like this, current human values would disallow procreation; however, this is not possible when it comes to non-human animals, who are guided by instinct. He takes the view that even if one does not agree that procreation is always morally bad, one should recognize procreation in wildlife as morally bad and something that ought to be prevented (at least in theory, not necessarily in practice). He maintains that non-intervention cannot be defended if we reject speciesism and that we should reject the unjustifiable dogma stating that what is happening in nature is what should be happening in nature.

We cannot allow ourselves to spuriously rationalize away the suffering that takes place in nature, and to forget the victims of the horrors of nature merely because that reality does not fit into our convenient moral theories, theories that ultimately just serve to make us feel consistent and good about ourselves in the face of an incomprehensibly bad reality.