Bureau of Land Management Triangle

| |

Flag of the Bureau of Land Management

| |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 1946 |

| Preceding agencies | |

| Jurisdiction | United States federal government |

| Headquarters | Main Interior Building 1849 C Street NW Room 5665, Washington, D.C., U.S. 20240 |

| Employees | 11,621 Permanent and 30,860 Volunteer (FY 2012) |

| Annual budget | $1,162,000,000 (FY 2014 operating) |

| Agency executive |

|

| Parent agency | U.S. Department of the Interior |

| Website | blm.gov |

Horses crossing a plain near the Simpson Park Wilderness Study Area in central Nevada, managed by the Battle Mountain BLM Field Office

Snow-covered cliffs of Snake River Canyon, Idaho, managed by the Boise District of the BLM

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) is an agency within the United States Department of the Interior that administers more than 247.3 million acres (1,001,000 km2) of public lands in the United States which constitutes one eighth of the landmass of the country. President Harry S. Truman created the BLM in 1946 by combining two existing agencies: the General Land Office and the Grazing Service. The agency manages the federal government's nearly 700 million acres (2,800,000 km2) of subsurface mineral estate located beneath federal, state and private lands severed from their surface rights by the Homestead Act of 1862. Most BLM public lands are located in these 12 western states: Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington and Wyoming.

This

map shows land owned by different federal government agencies. The

yellow represents the Bureau of Land Management's holdings.

The mission of the BLM is "to sustain the health, diversity, and

productivity of the public lands for the use and enjoyment of present

and future generations." Originally BLM holdings were described as "land nobody wanted" because homesteaders had passed them by. All the same, ranchers hold nearly 18,000 permits and leases for livestock grazing on 155 million acres (630,000 km2) of BLM public lands. The agency manages 221 wilderness areas, 27 national monuments and some 636 other protected areas as part of the National Conservation Lands (formerly known as the National Landscape Conservation System), totaling about 36 million acres (150,000 km2). In addition the National Conservation Lands include nearly 2,400 miles of Wild and Scenic Rivers, and nearly 6,000 miles of National Scenic and Historic Trails.

There are more than 63,000 oil and gas wells on BLM public lands. Total

energy leases generated approximately $5.4 billion in 2013, an amount

divided among the Treasury, the states, and Native American groups.

History

The BLM's roots go back to the Land Ordinance of 1785 and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787.

These laws provided for the survey and settlement of the lands that the

original 13 colonies ceded to the federal government after the American Revolution. As additional lands were acquired by the United States from Spain, France and other countries, the United States Congress directed that they be explored, surveyed, and made available for settlement. During the Revolutionary War, military bounty land was promised to soldiers who fought for the colonies. After the war, the Treaty of Paris of 1783, signed by the United States, England, France, and Spain, ceded territory to the United States. In the 1780s, other states relinquished their own claims to land in modern-day Ohio. By this time, the United States needed revenue to function. Land was sold so that the government would have money to survive. In order to sell the land, surveys needed to be conducted. The Land Ordinance of 1785 instructed a geographer to oversee this work as undertaken by a group of surveyors.

The first years of surveying were completed by trial and error; once

the territory of Ohio had been surveyed, a modern public land survey

system had been developed. In 1812, Congress established the General Land Office as part of the Department of the Treasury to oversee the disposition of these federal lands. By the early 1800s, promised bounty land claims were finally fulfilled.

Over the years, other bounty land and homestead laws were enacted to dispose of federal land. Several different types of patents existed.

These include cash entry, credit, homestead, Indian, military warrants,

mineral certificates, private land claims, railroads, state selections,

swamps, town sites, and town lots. A system of local land offices spread throughout the territories, patenting land that was surveyed via the corresponding Office of the Surveyor General of a particular territory. This pattern gradually spread across the entire United States. The laws that spurred this system with the exception of the General Mining Law of 1872 and the Desert Land Act of 1877 have since been repealed or superseded.

In the early 20th century, Congress took additional steps toward

recognizing the value of the assets on public lands and directed the Executive Branch to manage activities on the remaining public lands. The Mineral Leasing Act of 1920 allowed leasing, exploration, and production of selected commodities, such as coal, oil, gas, and sodium to take place on public lands. The Taylor Grazing Act of 1934 established the United States Grazing Service to manage the public rangelands by establishment of advisory boards that set grazing fees. The Oregon and California Revested Lands Sustained Yield Management Act of 1937, commonly referred as the O&C Act, required sustained yield management of the timberlands in western Oregon.

In 1946, the Grazing Service was merged with the General Land Office to form the Bureau of Land Management within the Department of the Interior. It took several years for this new agency to integrate and reorganize.

In the end, the Bureau of Land Management became less focused on land

disposal and more focused on the long term management and preservation

of the land.

The agency achieved its current form by combining offices in the

western states and creating a corresponding office for lands both east

of and alongside the Mississippi River.

As a matter of course, the BLM's emphasis fell on activities in the

western states as most of the mining, land sales, and federally owned

areas are located west of the Mississippi.

BLM personnel on the ground have typically been oriented toward

local interests, while bureau management in Washington are led by

presidential guidance. By means of the Federal Land Policy and Management Act

of 1976, Congress created a more unified bureau mission and recognized

the value of the remaining public lands by declaring that these lands

would remain in public ownership.

The law directed that these lands be managed with a view toward

"multiple use" defined as "management of the public lands and their

various resource values so that they are utilized in the combination

that will best meet the present and future needs of the American

people."

Since the Reagan

years of the 1980s, Republicans have often given priority to local

control and to grazing, mining and petroleum production, while Democrats

have more often emphasized environmental concerns even when granting

mining and drilling leases. In September 1996, then President Bill Clinton used his authority under the Antiquities Act to establish the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in southern Utah, the first of now 20 national monuments established on BLM lands and managed by the agency. The establishment of Grand Staircase-Escalante foreshadowed later creation of the BLM's National Landscape Conservation System in 2000. Use of the Antiquities Act authority, to the extent it effectively scuttled a coal mine to have been operated by Andalex Resources, delighted recreation and conservation enthusiasts but set up larger confrontations with state and local authorities.

BLM programs

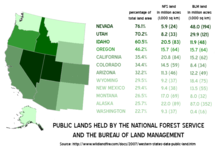

Most of the public lands held by the Bureau of Land Management are located in the western states.

- Grazing. The BLM manages livestock grazing on nearly 155 million acres (630,000 km2) million acres under the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934. The agency has granted more than 18,000 permits and leases to ranchers who graze their livestock, mostly cattle and sheep, at least part of the year on BLM public lands. Permits and leases generally cover a 10-year period and are renewable if the BLM determines that the terms and conditions of the expiring permit or lease are being met. The federal grazing fee is adjusted annually and is calculated using a formula originally set by Congress in the Public Rangelands Improvement Act of 1978. Under this formula, the grazing fee cannot fall below $1.35 per animal unit month (AUM), nor can any fee increase or decrease exceed 25 percent of the previous year's level. The grazing fee for 2014 was set at $1.35 per AUM, the same level as for 2013. Over time there has been a gradual decrease in the amount of grazing that takes place on BLM-managed land. Grazing on public lands has declined from 18.2 million AUMs in 1954 to 7.9 million AUMs in 2013.

- Mining. Domestic production from over 63,000 Federal "onshore" oil and gas wells on BLM lands accounts for 11 percent of the natural gas supply and five percent of the oil supply in the United States. BLM has on record a total of 290,000 mining claims under the General Mining Law of 1872. The BLM supports an all of the above energy approach, which includes oil and gas, coal, strategic minerals, and renewable energy resources such as wind, geothermal and solar—all of which may be developed on public lands and subject to free markets. This approach strengthens American energy security, supports job creation, and strengthens America's energy infrastructure. The BLM is also taking steps to make energy development on public lands easier by reviewing and streamlining it's business processes to serve industry and the American public. Even under the current administration's America first and energy independence the total mining claims on lands owned by the BLM has decreased while also the amount of rejected claims has increased. too put some context on this, the BLM oversees over 3.8 million mining claims. However, approximately 89% are closed mines with just over 10% of claims still being active. Of these active claims Nevada currently has the most at 203,705. The next closest state is California with 49,259.

- Coal leases. The BLM holds the coal mineral estate to more than 570 million acres (2,300,000 km2) where the owner of the surface is the federal government, a state or local government, or a private entity. As of 2013, the BLM had competitively granted 309 leases for coal mining to 474,252 acres (191,923 ha), an increase of 13,487 acres (5,458 ha) or nearly 3% increase in land subject to coal production over ten years' time.

- Recreation. The BLM administers 205,498 miles (330,717 km) of fishable streams, 2.2 million acres (8,900 km2) of lakes and reservoirs, 6,600 miles (10,600 km) of floatable rivers, over 500 boating access points, 69 National Back Country Byways, and 300 Watchable Wildlife sites. The agency also manages 4,500 miles (7,200 km) of National Scenic, National Historic and National Recreation Trails, as well as thousands of miles of multiple use trails used by motorcyclists, hikers, equestrians, and mountain bikers. In 2013, BLM lands received an estimated 61.7 million recreational visitors. Over 99% of BLM-managed lands are open to hunting, recreational shooting opportunities, and fishing.

- California Desert Conservation Area. The California Desert Conservation Area covers 25 million acres (100,000 km2) of land in southern California designated by Congress in 1976 by means of the Federal Land Policy and Management Act. BLM is charged with administering about 10 million acres (40,000 km2) of this fragile area with its potential for multiple uses in mind.

- Timberlands. The Bureau manages 55 million acres (220,000 km2) of forests and woodlands, including 11 million acres (45,000 km2) of commercial forest and 44 million acres (180,000 km2) of woodlands in 11 western states and Alaska.53 million acres (210,000 km2) are productive forests and woodlands on public domain lands and 2.4 million acres (9,700 km2) are on O&C lands in western Oregon.

Calm Before the Storm: Fatigued BLM Firefighters taking a break after a fire in Oregon in 2008

- Firefighting. Well in excess of 3,000 full-time equivalent firefighting personnel work for BLM. The agency fought 2,573 fires on BLM-managed lands in fiscal year 2013.

- Mineral rights on Indian lands. As part of its trust responsibilities, the BLM provides technical advice for minerals operations on 56 million acres (230,000 km2) of Indian lands.

- Leasing and Land Management of Split Estates. A split estate is similar to the broad form deeds used, starting in the early 1900s. It is a separation of mineral rights and surface rights on a property. The BLM manages split estates, but only in cases when the "surface rights are privately owned and the rights to the minerals are held by the Federal Government."

- Cadastral surveys. The BLM is the official record keeper for over 200 years' worth of cadastral survey records and plats as part of the Public Land Survey System. In addition, the Bureau still completes numerous new surveys each year, mostly in Alaska, and conducts resurveys to restore obliterated or lost original surveys.

- Abandoned mines. BLM maintains an inventory of known abandoned mines on the lands it manages. As of April 2014, the inventory contained nearly 46,000 sites and 85,000 other features. Approximately 23% of the sites had either been remediated, had reclamation actions planned or underway, or did not require further action. The remaining sites require further investigation. A 2008 Inspector General report alleges that BLM has for decades neglected the dangers represented by these abandoned mines.

- Energy corridors. Approximately 5,000 miles (8,000 km) of energy corridors for pipelines and transmission lines are located on BLM-managed lands.

- Helium. BLM operates the National Helium Reserve near Amarillo, Texas, a program begun in 1925 during the time of the Zeppelin Wars. Though the reserve had been set to be moved to private hands, it remains subject to oversight of the BLM under the provisions of the unanimously-passed Responsible Helium Administration and Stewardship Act of 2013.

- Revenue and fees. The BLM produces significant revenue for the United States budget. In 2009, public lands were expected to generate an estimated $6.2 billion in revenues, mostly from energy development. Nearly 43.5 percent of these funds are provided directly to states and counties to support roads, schools, and other community needs.

National Landscape Conservation System

Established in 2000, the National Landscape Conservation System is overseen by the BLM. The National Landscape Conservation System lands constitute just about 12% of the lands managed by the BLM. Congress passed Title II of the Omnibus Public Land Management Act of 2009 (Public Law 111-11) to make the system a permanent part of the public lands protection system in the United States.

By designating these areas for conservation, the law directed the BLM

to ensure these places are protected for future generations, similar to national parks and wildlife refuges.

| Category | Unit Type | Number | BLM acres | BLM miles |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Conservation Lands | National Monuments | 27 | 5,590,135 acres (22,622.47 km2) |

|

| National Conservation Lands | National Conservation Areas | 16 | 3,671,519 acres (14,858.11 km2) |

|

| National Conservation Lands | Areas Similar to National Conservation Areas | 5 | 436,164 acres (1,765.09 km2) |

|

| Wilderness | Wilderness Areas | 221 | 8,711,938 acres (35,255.96 km2) |

|

| Wilderness | Wilderness Study Areas | 528 | 12,760,472 acres (51,639.80 km2) |

|

| National Wild and Scenic Rivers | National Wild and Scenic Rivers | 69 | 1,001,353 acres (4,052.33 km2) | 2,423 miles (3,899 km) |

| National Trails System | National Historic Trails | 13 |

|

5,078 miles (8,172 km) |

| National Trails System | National Scenic Trails | 5 |

|

683 miles (1,099 km) |

|

|

Totals | 877 | About 36 million acres (150,000 km2) (some units overlap) | 8,184 miles (13,171 km) |

Source: BLM Resources and Statistics

Law enforcement and security

Lightning-sparked wildfires are frequent occurrences on BLM land in Nevada.

The BLM, through its Office of Law Enforcement & Security, functions as a federal law enforcement agency of the United States Government. BLM law enforcement rangers and special agents receive their training through Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers (FLETC). Full-time staffing for these positions approaches 300.

Uniformed rangers enforce laws and regulations governing BLM lands and resources.

As part of that mission, these BLM rangers carry firearms, defensive

equipment, make arrests, execute search warrants, complete reports and

testify in court.

They seek to establish a regular and recurring presence on a vast

amount of public lands, roads and recreation sites. They focus on the

protection of natural and cultural resources, other BLM employees and

visitors.

Given the many locations of BLM public lands, these rangers use

canines, helicopters, snowmobiles, dirt bikes and boats to perform their

duties.

By contrast BLM special agents are criminal investigators

who plan and conduct investigations concerning possible violations of

criminal and administrative provisions of the BLM and other statutes

under the United States Code.

Special agents are normally plain clothes officers who carry concealed

firearms, and other defensive equipment, make arrests, carry out complex

criminal investigations, present cases for prosecution to local United States Attorneys and prepare investigative reports. Criminal investigators occasionally conduct internal and civil claim investigations.

Wild horse and burro program

Mustangs run across Tule Valley, Utah

The BLM manages free-roaming horses and burros on public lands in ten western states. Though they are feral, the agency is obligated to protect them under the Wild and Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971 (WFRHBA). As the horses have few natural predators, populations have grown substantially.

WFRHBA as enacted provides for the removal of excess animals; the

destruction of lame, old, or sick animals; the private placement or

adoption of excess animals; and even the destruction of healthy animals

if range management required it. In fact, the destruction of healthy or unhealthy horses has almost never occurred. Pursuant to the Public Rangelands Improvement Act of 1978, the BLM has established 179 "herd management areas" (HMAs) covering 31.6 million acres (128,000 km2) acres where feral horses can be found on federal lands.

In 1973, BLM began a pilot project on the Pryor Mountains Wild Horse Range known as the Adopt-A-Horse initiative.

The program took advantage of provisions in the WFRHBA to allow private

"qualified" individuals to "adopt" as many horses as they wanted if

they could show that they could provide adequate care for the animals. At the time, title to the horses remained permanently with the federal government. The pilot project was so successful that BLM allowed it to go nationwide in 1976.

The Adopt-a-Horse program quickly became the primary method of removing

excess feral horses from BLM land given the lack of other viable

methods. The BLM also uses limited amounts of contraceptives in the herd, in the form of PZP

vaccinations; advocates say that additional use of these vaccines would

help to diminish the excess number of horses currently under BLM

management.

Despite the early successes of the adoption program, the BLM has

struggled to maintain acceptable herd levels, as without natural

predators, herd sizes can double every four years.

As of 2014, there were more than 49,000 horses and burros on

BLM-managed land, exceeding the BLM's estimated "appropriate management

level" (AML) by almost 22,500.

The Bureau of Land Management has implemented several programs

and has developed partnerships as part of their management plan for

preserving wild burros and horses in the United States. There are

several herds of horses and burros roaming free on 26.9 million acres of

range spread out in ten western states. It is essential to maintain a

balance that keeps herd management land and animal population healthy.

Some programs and partnerships include the Mustang Heritage Foundation,

U.S. Border Patrol, Idaho 4H, Napa Mustang Days and Little Book Cliffs

Darting Team. These partnerships help with adoption and animal

population as well as education and raising awareness about wild horses

and burros.

Renewable energy

Aerial photograph of Ivanpah Solar Power Facility located on BLM-managed land in the Mojave Desert

In 2009, BLM opened Renewable Energy Coordination Offices in order to

approve and oversee wind, solar, biomass, and geothermal projects on

BLM-managed lands.

The offices were located in the four states where energy companies had

shown the greatest interest in renewable energy development: Arizona, California, Nevada, and Wyoming.

- Solar energy. In 2010, BLM approved the first utility-scale solar energy projects on public land. As of 2014, 70 solar energy projects covering 560,000 acres (2,300 km2) had been proposed on public lands managed by BLM primarily located in Arizona, California, and Nevada. To date, it has approved 29 projects that have the potential to generate 8,786 megawatts of renewable energy or enough energy to power roughly 2.6 million homes. The projects range in size from a 45-megawatt photovoltaic system on 422 acres (171 ha) to a 1,000-megawatt parabolic trough system on 7,025 acres (2,843 ha).

- Wind energy. BLM manages 20.6 million acres (83,000 km2) of public lands with wind potential. It has authorized 39 wind energy development projects with a total approved capacity of 5,557 megawatts or enough to supply the power needs of over 1.5 million homes. In addition, BLM has authorized over 100 wind energy testing sites.

- Geothermal energy. BLM manages 59 geothermal leases in producing status, with a total capacity of 1,500 megawatts. This amounts to over 40 percent of the geothermal energy capacity in the United States.

- Biomass and bioenergy. Its large portfolio of productive timberlands leaves BLM with woody biomass among its line of forest products. The biomass is composed of "smaller diameter materials" and other debris that result from timber production and forest management. Though the use of these materials as a renewable resource is nascent, the agency is engaged in pilot projects to increase the use of its biomass supplies in bioenergy programs.