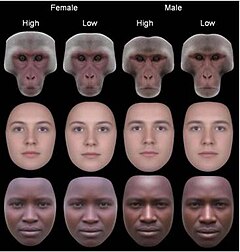

Concealed ovulation or hidden estrus in a species is the lack of any perceptible change in an adult female (for instance, a change in appearance or scent) when she is fertile and near ovulation. Some examples of perceptible changes are swelling and redness of the genitalia in baboons and bonobos, and pheromone release in the feline family. In contrast, the females of humans and a few other species that undergo hidden estrus have few external signs of fecundity, making it difficult for a mate to consciously deduce, by means of external signs only, whether or not a female is near ovulation.

Human females

In humans, an adult woman's fertility peaks for a few days during each roughly monthly cycle. The frequency and length of fertility (the time when a woman can become pregnant) is highly variable between women, and can slightly change for each woman over the course of her lifespan. Humans are considered to have concealed ovulation because there is no outward physiological sign, either to a woman herself or to others, that ovulation, or biological fertility, is occurring. Knowledge of the fertility cycle, learned through experience or from educational sources, can allow a woman to estimate her own level of fertility at a given time (fertility awareness). Whether other humans, potential reproductive partners in particular, can detect fertility in women through behavioral or invisible biological cues is highly debated. Scientists and laypersons are interested in this question because it has implications for human social behavior, and could theoretically offer biological explanations for some human sexual behavior. However, the science here is weak, due to a relatively small number of studies.

Several small studies have found that fertile women appear more attractive to men than women during infertile portions of her menstrual cycle, or women using hormonal contraception. It has also been suggested that a woman's voice may become more attractive to men during this time. Two small studies of monogamous human couples found that women initiated sex significantly more frequently when fertile, but male-initiated sex occurred at a constant rate, without regard to the woman's phase of menstrual cycle. It may be that a woman's awareness of men's courtship signals increases during her highly fertile phase due to an enhanced olfactory awareness of chemicals specifically found in men's body odor.

Analyses of data provided by the post-1998 U.S. Demographic and Health Surveys found no variation in the occurrence of coitus in the menstrual phases (except during menstruation itself). This is contrary to other studies, which have found female sexual desire and extra-pair copulations (EPCs) to increase during the midfollicular to ovulatory phases (that is, the highly fertile phase). These findings of differences in woman-initiated versus man-initiated sex are likely caused by the woman's subconscious awareness of her ovulation cycle (because of hormonal changes causing her to feel increased sexual desire), contrasting with the man's inability to detect ovulation because of its being "hidden".

In 2008, researchers announced the discovery in human semen of hormones usually found in ovulating women. They theorized that follicle stimulating hormone, luteinising hormone, and estradiol may encourage ovulation in women exposed to semen. These hormones are not found in the semen of chimpanzees, suggesting this phenomenon may be a human male counter-strategy to concealed ovulation in human females. Other researchers are skeptical that the low levels of hormones found in semen could have any effect on ovulation. One group of authors has theorized that concealed ovulation and menstruation were key factors in the development of symbolic culture in early human society.

Evolutionary hypotheses

Evolutionary psychologists have advanced a number of different possible explanations for concealed ovulation. Some posit that the lack of signaling in some species is a trait retained from evolutionary ancestors, not something that existed previously and later disappeared. If signaling is supposed to have existed and was lost, then it could have been merely due to reduced adaptive importance and lessened selection, or due to direct adaptive advantages for the concealment of ovulation. Yet another possibility (regarding humans specifically) is that while highly specific signaling of ovulation is absent, human female anatomy evolved to mimic permanent signaling of fertility.

Paternal investment hypothesis

The paternal investment hypothesis is strongly supported by many evolutionary biologists. Several hypotheses regarding human evolution integrate the idea that women increasingly required supplemental paternal investment in their offspring. The shared reliance on this idea across several hypotheses concerning human evolution increases its significance in terms of this specific phenomenon.

This hypothesis suggests that women concealed ovulation to obtain men's aid in rearing offspring. Schröder summarizes this hypothesis outlined in Alexander and Noonan's 1979 paper: if women no longer signaled the time of ovulation, men would be unable to detect the exact period in which they were fecund. This led to a change in men's mating strategy: rather than mating with multiple women in the hope that some of them, at least, were fecund during that period, men instead chose to mate with a particular woman repeatedly throughout her menstrual cycle. A mating would be successful in resulting in conception when it occurred during ovulation, and thus, frequent matings, necessitated by the effects of concealed ovulation, would be most evolutionarily successful. A similar hypothesis was proposed by Lovejoy in 1981 that argued that concealed ovulation, reduced canines and bipedalism evolved from a reproductive strategy where males provisioned food resources to his paired female and dependent offspring.

Continuous female sexual receptivity suggests human sexuality is not solely defined by reproduction; a large part of it revolves around conjugal love and communication between partners. Copulations between partners while the woman is pregnant or in the infertile period of her menstrual cycle do not achieve conception, but do strengthen the bond between these partners. Therefore, the increased frequency of copulations due to concealed ovulation are thought to have played a role in fostering pair bonds in humans.

The pair bond would be very advantageous to the reproductive fitness of both partners throughout the period of pregnancy, lactation, and rearing of offspring. Pregnancy, lactation and caring for post-lactation offspring require vast amounts of energy and time on the part of the woman. She must at first consume more food, then provide food to her offspring, while her ability to forage is reduced throughout. Supplemental male investment in the mother and her offspring is advantageous to all parties. While the man supplements the woman's limited gathered food, the woman is enabled to devote the necessary time and energy to the care of their offspring. The offspring benefits from the supplemental investment, in the form of food and defense from the father, and receives the full attention and resources of the mother. Through this shared parental investment, both man and woman would increase their offspring's chances for survival, thereby increasing their reproductive fitness. In this way, natural selection would favor the establishment of pair bonds in humans. To the extent that concealed ovulation strengthened pair bonding, selective pressure would favor concealed ovulation as well.

Another, more recent, hypothesis is that concealed ovulation is an adaptation in response to a promiscuous mating system, similar to that of our closest evolutionary relatives, bonobos and chimpanzees. The theory is that concealed ovulation evolved in women to lessen paternity certainty, which would both lessen the chances of infanticide (as a father is less likely to kill offspring that might be his), and potentially increase the number of men motivated to assist her in caring for her offspring (partible paternity). This is supported by the fact that all other mammals with concealed ovulation, such as dolphins and gray langurs, are promiscuous, and that the only other ape species that have multi-male communities, as humans do, are promiscuous. It is argued that evidence such as the Coolidge effect, showing that a man does not seem to be naturally geared towards sexual mate-guarding behavior (that is, preventing other males from having access to his sexual partner), supports the conclusion that sexual monogamy (though perhaps not social monogamy and/or pair bonding) was rare in early modern humans.

Reduced infanticide hypothesis

This hypothesis suggests the adaptive advantage for women who had hidden estrus would be a reduction in the possibility of infanticide by men, as they would be unable to reliably identify, and kill, their rivals' offspring. This hypothesis is supported by recent studies of wild Hanuman langurs, documenting concealed ovulation, and frequent matings with males outside their fertile ovulatory period. Heistermann et al. hypothesize that concealed ovulation is used by women to confuse paternity and thus reduce infanticide in primates. He explains that as ovulation is always concealed in women, men can only determine paternity (and thus decide on whether to kill the woman's child) probabilistically, based on his previous mating frequency with her, and so he would be unable to escape the possibility that the child might be his own, even if he were aware of promiscuous matings on the woman's part.

Sex and reward hypothesis

Schröder reviews a hypothesis by Symons and Hill, that after hunting, men exchanged meat for sex with women. Women who continuously mimicked estrus may have benefited from more meat than those that did not. If this occurred with enough frequency, then a definite period of estrus would have been lost, and with it sexual signaling specific to ovulation would have disappeared.

Social-bonding hypothesis

Schröder presents the idea of a "gradual diminution of mid-cycle estrus and concomitant continuous sexual receptivity in human women" because it facilitated orderly social relationships throughout the menstrual cycle by eliminating the periodic intensification of male–male aggressiveness in competition for mates. The extended estrous period of the bonobo (reproductive-age females are in heat for 75% of their menstrual cycle) has been said to have a similar effect to the lack of a "heat" in women. While concealed human ovulation may have evolved in this fashion, extending estrus until it was no longer a distinct period, as paralleled in the bonobo, this theory of why concealed ovulation evolved has frequently been rejected. Schröder outlines the two objections to this hypothesis: (1) natural selection would need to work at a level above the individual, which is difficult to prove; and (2) selection, because it acts on the individuals with the most reproductive success, would thus favor greater reproductive success over social integration at the expense of reproductive success.

However, since 1993 when that was written, group selection models have seen a resurgence. (See group selection, reciprocal altruism, and kin selection.)

Cuckoldry hypothesis

Schröder in his review writes that Benshoof and Thornhill hypothesized that estrus became hidden after monogamous relationships became the norm in Homo erectus. Concealed ovulation allowed the woman to mate secretly at times with a genetically superior man, and thus gain the benefit of his genes for her offspring, while still retaining the benefits of the pair bond with her usual sexual partner. Her usual sexual partner would have little reason to doubt her fidelity, because of the concealed ovulation, and would have high, albeit unfounded, paternity confidence in her offspring. His confidence would encourage him to invest his time and energy in assisting her to care for the child, even though it was not his own. Again, the idea of a man's investment being vital to the child's survival is a central fixture of a hypothesis regarding concealed ovulation, even as the evolutionary benefits accrue to the child, the woman, and her clandestine partner, and not to her regular sexual partner.

As a side effect of bipedalism

Pawlowski presents the importance of bipedalism to the mechanics and necessity of ovulation signaling. The more open savannah environment inhabited by early humans brought greater danger from predators. This would have caused humans to live in denser groups, and, in such a scenario, the long-distance sexual signaling provided by female genital swellings would have lost its function. Concealed ovulation is thus argued to be a loss of function evolutionary change rather than an adaptation. Thermoregulatory systems were also modified in humans with the move to the savannah to conserve water. It is thought that female genital swellings would have incurred added cost because of ineffective evaporation of water from the area. Pawlowski continues by saying the change to bipedalism in early hominins changed both the position of female genitals and the line of vision of males. Since males could no longer constantly see the female genitals, swelling of them during estrus as a mode of signaling would have become useless. Also, anogenital swelling at each ovulatory period may have interfered with the mechanics of bipedal locomotion, and selection may have favored females who were less hindered by this occurrence. This hypothesis ultimately concludes that bipedalism, which was strongly selected for, caused the physiological changes and a loss of function of sexual signaling through female genital swelling, leading to the concealed ovulation we now observe.

Pawlowski's paper offers views that differ from the other hypotheses regarding concealed ovulation in that it pinpoints physiological changes in early humans as the cause of concealed ovulation rather than social or behavioral ones. One of the strengths of this is derived from the other hypotheses' weaknesses – it is difficult to track the evolution of a behavior as it leaves no verifiable evidence in the form of bone or DNA. However, the fact that the Hanuman langurs also display some concealed ovulation and that it is not directly caused by a physiological change to bipedalism may suggest bipedalism was not, at least, the sole cause of concealed ovulation in humans. As stated earlier, it is possible for many elements of different hypotheses to be true regarding the selective pressures for concealed ovulation in humans.