From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

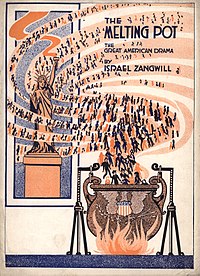

The image of the United States as a melting pot was popularized by the 1908 play

The Melting Pot.

The melting pot is a monocultural metaphor for a heterogeneous society becoming more homogeneous, the different elements "melting together" with a common culture; an alternative being a homogeneous society becoming more heterogeneous

through the influx of foreign elements with different cultural

backgrounds, possessing the potential to create disharmony within the

previous culture. It can also create a harmonious hybridized society

known as cultural amalgamation. Historically, it is often used to describe the cultural integration of immigrants to the United States. A related concept has been defined as "cultural additivity."

The melting-together metaphor was in use by the 1780s.

The exact term "melting pot" came into general usage in the United

States after it was used as a metaphor describing a fusion of

nationalities, cultures and ethnicities in the 1908 play of the same name.

The desirability of assimilation and the melting pot model has been rejected by proponents of multiculturalism, who have suggested alternative metaphors to describe the current American society, such as a salad bowl, or kaleidoscope, in which different cultures mix, but remain distinct in some aspects.

The melting pot continues to be used as an assimilation model in

vernacular and political discourse along with more inclusive models of

assimilation in the academic debates on identity, adaptation and

integration of immigrants into various political, social and economic

spheres.

Origins of the term

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the metaphor of a "crucible"

or "smelting pot" was used to describe the fusion of different

nationalities, ethnicities and cultures. It was used together with

concepts of the United States as an ideal republic and a "city upon a hill" or new promised land. It was a metaphor for the idealized process of immigration and colonization

by which different nationalities, cultures and "races" (a term that

could encompass nationality, ethnicity and racist views of humanity)

were to blend into a new, virtuous community, and it was connected to utopian visions of the emergence of an American "new man".

While "melting" was in common use the exact term "melting pot" came

into general usage in 1908, after the premiere of the play The Melting Pot by Israel Zangwill.

The first use in American literature of the concept of immigrants

"melting" into the receiving culture are found in the writings of J. Hector St. John de Crevecoeur. In his Letters from an American Farmer

(1782) Crevecoeur writes, in response to his own question, "What then

is the American, this new man?" that the American is one who "leaving

behind him all his ancient prejudices and manners, receives new ones

from the new mode of life he has embraced, the government he obeys, and

the new rank he holds. He becomes an American by being received in the

broad lap of our great Alma Mater. Here individuals of all nations are melted into a new race of men, whose labors and posterity will one day cause great changes in the world."

...whence came all these people?

They are a mixture of English, Scotch, Irish, French, Dutch, Germans,

and Swedes... What, then, is the American, this new man? He is either a

European or the descendant of a European; hence that strange mixture of

blood, which you will find in no other country. I could point out to you

a family whose grandfather was an Englishman, whose wife was Dutch,

whose son married a French woman, and whose present four sons have now

four wives of different nations. He is an American, who, leaving behind

him all his ancient prejudices and manners, receives new ones from the

new mode of life he has embraced, the new government he obeys, and the

new rank he holds.... The Americans were once scattered all over Europe;

here they are incorporated into one of the finest systems of population

which has ever appeared.

— J. Hector St. John de Crevecoeur, Letters from an American Farmer

In 1845, Ralph Waldo Emerson, alluding to the development of European civilization out of the medieval Dark Ages, wrote in his private journal of America as the Utopian product of a culturally and racially mixed "smelting pot", but only in 1912 were his remarks first published.

A magazine article in 1876 used the metaphor explicitly:

The fusing process goes on as in a blast-furnace;

one generation, a single year even—transforms the English, the German,

the Irish emigrant into an American. Uniform institutions, ideas,

language, the influence of the majority, bring us soon to a similar

complexion; the individuality of the immigrant, almost even his traits

of race and religion, fuse down in the democratic alembic like chips of

brass thrown into the melting pot.

In 1893, historian Frederick Jackson Turner also used the metaphor of immigrants melting into one American culture. In his essay The Significance of the Frontier in American History, he referred to the "composite nationality" of the American people, arguing that the frontier had functioned as a "crucible"

where "the immigrants were Americanized, liberated and fused into a

mixed race, English in neither nationality nor characteristics".

In his 1905 travel narrative The American Scene, Henry James discusses cultural intermixing in New York City as a "fusion, as of elements in solution in a vast hot pot".

According to some recent findings, the term has been used since the late 18th century.

The exact term "melting pot" came into general usage in the United

States after it was used as a metaphor describing a fusion of

nationalities, cultures and ethnicities in the 1908 play of the same name, first performed in Washington, D.C., where the immigrant protagonist declared:

Understand

that America is God's Crucible, the great Melting-Pot where all the

races of Europe are melting and re-forming! Here you stand, good folk,

think I, when I see them at Ellis Island, here you stand in your fifty

groups, your fifty languages, and histories, and your fifty blood

hatreds and rivalries. But you won't be long like that, brothers, for

these are the fires of God you've come to—these are fires of God. A fig

for your feuds and vendettas! Germans and Frenchmen, Irishmen and

Englishmen, Jews and Russians—into the Crucible with you all! God is

making the American.

- Israel Zangwill

In The Melting Pot (1908), Israel Zangwill combined a romantic

denouement with an utopian celebration of complete cultural

intermixing. The play was an adaptation of William Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet,

set in New York City. The play's immigrant protagonist David Quixano, a

Russian Jew, falls in love with Vera, a fellow Russian immigrant who is

Christian. Vera is an idealistic settlement house

worker and David is a composer struggling to create an "American

symphony" to celebrate his adopted homeland. Together they manage to

overcome the old world animosities that threaten to separate them. But

then David discovers that Vera is the daughter of the Tsarist officer

who directed the pogrom

that forced him to flee Russia. Horrified, he breaks up with her,

betraying his belief in the possibility of transcending religious and

ethnic animosities. However, unlike Shakespeare's tragedy, there is a

happy ending. At the end of the play the lovers are reconciled.

Reunited with Vera and watching the setting sun gilding the Statue of Liberty,

David Quixano has a prophetic vision: "It is the Fires of God round His

Crucible. There she lies, the great Melting-Pot—Listen! Can't you hear

the roaring and the bubbling? There gapes her mouth, the harbor where a

thousand mammoth feeders come from the ends of the world to pour in

their human freight". David foresees how the American melting pot will

make the nation's immigrants transcend their old animosities and

differences and will fuse them into one people: "Here shall they all

unite to build the Republic of Man and the Kingdom of God. Ah, Vera,

what is the glory of Rome and Jerusalem where all nations and races come

to worship and look back, compared with the glory of America, where all

races and nations come to labour and look forward!"

Zangwill thus combined the metaphor of the "crucible" or "melting

pot" with a celebration of the United States as an ideal republic and a

new promised land. The prophetic words of his Jewish protagonist

against the backdrop of the Statue of Liberty allude to Emma Lazarus's famous poem The New Colossus (1883), which celebrated the statue as a symbol of American democracy and its identity as an immigrant nation.

Zangwill concludes his play by wishing, "Peace, peace, to all ye

unborn millions, fated to fill this giant continent—the God of our

children give you Peace." Expressing his hope that through this forging

process the "unborn millions" who would become America's future citizens

would become a unified nation at peace with itself despite its ethnic

and religious diversity.

United States

In terms of immigrants to the United States, the "melting pot" process has been equated with Americanization, that is, cultural assimilation and acculturation. The "melting pot" metaphor implies both a melting of cultures and intermarriage of ethnicities,

yet cultural assimilation or acculturation can also occur without

intermarriage. Thus African-Americans are fully culturally integrated

into American culture and institutions. Yet more than a century after

the abolition of slavery, intermarriage between African-Americans and

other ethnicities is much less common than between different white

ethnicities, or between white and Asian ethnicities. Intermarriage

between whites and non-whites, and especially African-Americans, was a

taboo in the United States for a long time, and was illegal in many US

states (see anti-miscegenation laws) until 1967.

Native Americans

Intermarriage between Euro-American men and Native American

women has been common since colonial days and there was also

significant intermarriage in the 18th and early 19th centuries between

African Americans, whether free or fugitive slaves, and Native

Americans, especially in Florida. In the 21st century some 7.5 million

Americans claim Native American ancestry. In the 1920s the nation welcomed celebrities of Native American background, especially Will Rogers and Jim Thorpe, as well as Vice President Charles Curtis, who had been brought up on a reservation and identified with his Indian heritage.

Miscegenation

The mixing of whites and blacks, resulting in multiracial children, for which the term "miscegenation"

was coined in 1863, was a taboo, and most whites opposed marriages

between whites and blacks. In many states, marriage between whites and

non-whites was even prohibited by state law through anti-miscegenation laws. As a result, two kinds of "mixture talk" developed:

As the new word—miscegenation—became associated with black-white mixing,

a preoccupation of the years after the Civil War, the residual European

immigrant aspect of the question of [ethnoracial mixture] came to be

more than ever a thing apart, discussed all the more easily without any

reference to the African-American aspect of the question. This

separation of mixture talk into two discourses facilitated, and was in

turn reinforced by, the process Matthew Frye Jacobson has detailed whereby European immigrant groups became less ambiguously white and more definitely "not black".

By the early 21st century, many white Americans celebrated the impact

of African-American culture, especially in sports and music, and

marriages between white Americans and African-Americans were becoming

much more common. Israel Zangwill saw this coming in the early 20th

century: "However scrupulously and justifiably America avoids

intermarriage with the negro, the comic spirit cannot fail to note

spiritual miscegenation which, while clothing, commercializing, and

Christianizing the ex-African, has given 'rag-time' and the sex-dances that go with it, first to white America and then to the whole white world."

Multiracial influences on culture

White Americans long regarded some elements of African-American culture

quintessentially "American", while at the same time treating African

Americans as second-class citizens. White appropriation, stereotyping

and mimicking of black culture played an important role in the

construction of an urban popular culture in which European immigrants

could express themselves as Americans, through such traditions as blackface, minstrel shows and later in jazz and in early Hollywood cinema, notably in The Jazz Singer (1927).

Analyzing the "racial masquerade" that was involved in creation

of a white "melting pot" culture through the stereotyping and imitation

of black and other non-white cultures in the early 20th century,

historian Michael Rogin has commented: "Repudiating 1920s nativism,

these films [Rogin discusses The Jazz Singer, Old San Francisco (1927), Whoopee! (1930), King of Jazz

(1930) celebrate the melting pot. Unlike other racially stigmatized

groups, white immigrants can put on and take off their mask of

difference. But the freedom promised immigrants to make themselves over

points to the vacancy, the violence, the deception, and the melancholy

at the core of American self-fashioning".

Since World War II, the idea of the melting pot has become more

racially inclusive in the United States, gradually extending also to

acceptance of marriage between whites and non-whites.

Ethnicity in films

This

trend towards greater acceptance of ethnic and racial minorities was

evident in popular culture in the combat films of World War II, starting

with Bataan

(1943). This film celebrated solidarity and cooperation between

Americans of all races and ethnicities through the depiction of a

multiracial American unit. At the time blacks and Japanese in the armed

forces were still segregated, while Chinese and Indians were in

integrated units.

Historian Richard Slotkin sees Bataan

and the combat genre that sprang from it as the source of the "melting

pot platoon", a cinematic and cultural convention symbolizing in the

1940s "an American community that did not yet exist", and thus

presenting an implicit protest against racial segregation. However,

Slotkin points out that ethnic and racial harmony within this platoon is

predicated upon racist hatred for the Japanese enemy: "the emotion

which enables the platoon to transcend racial prejudice is itself a

virulent expression of racial hatred...The final heat which blends the

ingredients of the melting pot is rage against an enemy which is fully

dehumanized as a race of 'dirty monkeys.'" He sees this racist rage as

an expression of "the unresolved tension between racialism and civic

egalitarianism in American life".

Hawaii

In Hawaii, as Rohrer (2008) argues, there are two dominant discourses of racial politics, both focused on "haole"

(white people or whiteness in Hawaii) in the islands. The first is the

discourse of racial harmony representing Hawaii as an idyllic racial

paradise with no conflict or inequality. There is also a competing

discourse of discrimination against nonlocals, which contends that

"haoles" and nonlocal people of color are disrespected and treated

unfairly in Hawaii. As negative referents for each other, these

discourses work to reinforce one another and are historically linked.

Rohrer proposes that the question of racial politics be reframed toward

consideration of the processes of racialization themselves—toward a new

way of thinking about racial politics in Hawaii that breaks free of the

not racist/racist dyad.

Olympics

Throughout

the history of the modern Olympic Games, the theme of the United States

as a melting pot has been employed to explain American athletic

success, becoming an important aspect of national self-image. The

diversity of American athletes in the Olympic Games in the early 20th

century was an important avenue for the country to redefine a national

culture amid-a massive influx of immigrants, as well as American Indians

(represented by Jim Thorpe in 1912) and blacks (represented by Jesse Owens in 1936). In the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City, two black American athletes with gold and bronze medals saluted the U.S. national anthem with a "Black Power" salute that symbolized rejection of assimilation.

The international aspect of the games allowed the United States

to define its pluralistic self-image against the monolithic traditions

of other nations. American athletes served as cultural ambassadors of American exceptionalism,

promoting the melting pot ideology and the image of America as a

progressive nation based on middle-class culture. Journalists and other

American analysts of the Olympics framed their comments with patriotic

nationalism, stressing that the success of U.S. athletes, especially in

the high-profile track-and-field events, stemmed not from simple

athletic prowess but from the superiority of the civilization that

spawned them.

Following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City

strongly revived the melting pot image, returning to a bedrock form of

American nationalism and patriotism. The reemergence of Olympic melting

pot discourse was driven especially by the unprecedented success of African Americans, Mexican Americans, Asian Americans, and Native Americans in events traditionally associated with Europeans and white North Americans such as speed skating and the bobsled.

The 2002 Winter Olympics was also a showcase of American religious

freedom and cultural tolerance of the history of Utah's large majority

population of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, as well representation of Muslim Americans and other religious groups in the U.S. Olympic team.

Melting pot and cultural pluralism

The concept of multiculturalism was preceded by the concept of cultural pluralism,

which was first developed in the 1910s and 1920s, and became widely

popular during the 1940s. The concept of cultural pluralism first

emerged in the 1910s and 1920s among intellectual circles out of the

debates in the United States over how to approach issues of immigration

and national identity.

The First World War and the Russian Revolution caused a "Red Scare" in the US, which also fanned feelings of xenophobia. During and immediately after the First World War, the concept of the melting pot was equated by nativists with complete cultural assimilation towards an Anglo-American

norm ("Anglo-conformity") on the part of immigrants, and immigrants who

opposed such assimilation were accused of disloyalty to the United

States.

The newly popularized concept of the melting pot was frequently

equated with "Americanization", meaning cultural assimilation, by many

"old stock" Americans. In Henry Ford's

Ford English School (established in 1914), the graduation ceremony for

immigrant employees involved symbolically stepping off an immigrant ship

and passing through the melting pot, entering at one end in

costumes designating their nationality and emerging at the other end in

identical suits and waving American flags.

Opposition to the absorption of millions of immigrants from

Southern and Eastern Europe was especially strong among popular writers

such as Madison Grant and Lothrop Stoddard, who believed in the "racial" superiority of Americans of Northern European descent as member of the "Nordic race",

and therefore demanded immigration restrictions to stop a

"degeneration" of America's white racial "stock". They believed that

complete cultural assimilation of the immigrants from Southern and

Eastern Europe was not a solution to the problem of immigration because

intermarriage with these immigrants would endanger the racial purity

of Anglo-Americans. The controversy over immigration faded away after

immigration restrictions were put in place with the enactment of the Johnson-Reed Act in 1924.

In response to the pressure exerted on immigrants to culturally

assimilate and also as a reaction against the denigration of the culture

of non-Anglo white immigrants by Nativists, intellectuals on the left,

such as Horace Kallen in Democracy Versus the Melting-Pot (1915), and Randolph Bourne in Trans-National America (1916), laid the foundations for the concept of cultural pluralism. This term was coined by Kallen.

Randolph Bourne, who objected to Kallen's emphasis on the inherent

value of ethnic and cultural difference, envisioned a "trans-national"

and cosmopolitan America. The concept of cultural pluralism was popularized in the 1940s by John Dewey.

In the United States, where the term melting pot is still commonly used, the ideas of cultural pluralism and multiculturalism have, in some circles, taken precedence over the idea of assimilation. Alternate models where immigrants retain their native cultures such as the "salad bowl" or the "symphony" are more often used by sociologists to describe how cultures and ethnicities mix in the United States. Mayor David Dinkins,

when referring to New York City, described it as "not a melting pot,

but a gorgeous mosaic...of race and religious faith, of national origin

and sexual orientation – of individuals whose families arrived yesterday

and generations ago..."

Nonetheless, the term assimilation is still used to describe the ways

in which immigrants and their descendants adapt, such as by increasingly

using the national language of the host society as their first

language.

Since the 1960s, much research in Sociology and History has

disregarded the melting pot theory for describing interethnic relations

in the United States and other countries. The theory of multiculturalism offers alternative analogies for ethnic interaction including salad bowl theory, or, as it is known in Canada, the cultural mosaic.

In the 21st century, most second and third- generation descendants of

immigrants in the United States continue to assimilate into broader

American culture, while American culture itself increasingly

incorporates food and music influences of foreign cultures. Similar

patterns of integration can be found in Western Europe, particularly

among black citizens of countries such as Britain, the Netherlands,

France, Belgium, and Germany.

Nevertheless, some prominent scholars, such as Samuel P. Huntington in Who Are We? The Challenges to America's National Identity,

have expressed the view that the most accurate explanation for

modern-day United States culture and inter-ethnic relations can be found

somewhere in a fusion of some of the concepts and ideas contained in

the melting pot, assimilation, and Anglo-conformity models. Under this

theory, it is asserted that the United States has one of the most

homogeneous cultures of any nation in the world. This line of thought

holds that this American national culture derived most of its traits and

characteristics from the Northern European settlers who colonized North America.

When more recent immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe brought

their various cultures to America at the beginning of the 20th century,

they changed the American cultural landscape just very slightly and, for

the most part, assimilated into America's pre-existing culture, which

had its origins in Northwestern Europe.

The decision of whether to support a melting-pot or multicultural

approach has developed into an issue of much debate within some

countries. For example, the French

and British governments and populace are currently debating whether

Islamic cultural practices and dress conflict with their attempts to

form culturally unified countries.

Use in other regions

Antiquity

Gold

croeseid of

Croesus c.550 BC, depicting the Lydian lion and Greek bull - partly in recognition of transnational parentage.

In

more ancient times, some marriages between distinctly different tribes

and nations were due to royalty trying to form alliances with or to

influence other kingdoms or to dissuade marauders or slave traders. Two

examples, Hermodike I c.800BC and Hermodike II c.600BC were Greek princesses from the house of Agamemnon

who married kings from what is now Central Turkey. These unions

resulted in the transfer of ground-breaking technological skills into

Ancient Greece, respectively, the phonetic written script and the use of

coinage (to use a token currency, where the value is guaranteed by the

state).

Both inventions were rapidly adopted by surrounding nations through

trade and cooperation and have been of fundamental benefit to the

progress of civilization.

Mexico

Mexico

has seen a variety of cultural influences over the years, and in its

history has adopted a mixed assimilationist/multiculturalist policy.

Mexico, beginning with the conquest of the Aztecs,

had entered a new global empire based on trade and immigration. In the

16th and 17th centuries, waves of Spanish, and to a lesser extent,

African and Filipino culture became embedded into the fabric of Mexican

culture. It is important to note, however, that from a Mexican

standpoint, the immigrants and their culture were no longer considered

foreign, but Mexican in their entirety. The food, art, and even heritage

were assimilated into a Mexican identity. Upon the independence of Mexico,

Mexico began receiving immigrants from Central Europe, Eastern Europe,

the Middle East and Asia, again, bringing many cultural influences but

being quickly labeled as Mexican, unlike in the United States and

Canada, where other culture is considered foreign. This assimilation is

very evident, even in Mexican society today: for example, banda,

a style of music originating in northern Mexico, is simply a Mexican

take on Central European music brought by immigrants in the 18th

century. Mexico's thriving beer industry was also the result of German

brewers finding refuge in Mexico. Many famous Mexicans are actually of

Arab descent; Salma Hayek and Carlos Slim. The coastal states of Guerrero and Veracruz are inhabited by citizens of African descent. Mexico's national policy is based on the concept of mestizaje, a word meaning "to mix".

South America

Argentina

As with other areas of new settlement such as Canada, Australia, the United States, Brazil, New Zealand, The United Arab Emirates, and Singapore, Argentina is considered a country of immigrants.

When it is considered that Argentina was second only to the United

States (27 million of immigrants) in the number of immigrants received,

even ahead of such other areas of newer settlement like Australia,

Brazil, Canada and New Zealand; and that the country was scarcely populated following its independence, the impact of the immigration to Argentina becomes evident.

Most Argentines are descended from colonial-era settlers and of the 19th- and 20th-century immigrants from Europe. An estimated 8% of the population is Mestizo, and a further 4% of Argentines are of Arab (in Argentina the Arab ethnicity is considered among the White people, just like in the US Census) or Asian heritage. In the last national census, based on self-identification, 600,000 Argentines (2% of the population) declared to be Amerindians

Although various genetic tests show that in average, Argentines have 20

to 30% indigenous ancestry, which leads many who are culturally

European, to identify as white, even though they are genetically

mestizo. Most of the 6 million European And Arab immigrants arriving

between 1850 and 1950, regardless of origin, settled in several regions

of the country. Due to this large-scale European and Arab immigration,

Argentina's population more than doubled, although half ended up

returning to Europe, The Middle East or ended up settling in the United

States or Canada.

Immigrant population in Argentina (1869–1991)

The majority of these European immigrants came from Spain and Italy

mostly, but to a lesser extent, Germany, France, and Russia. Small

communities also descend from Switzerland, Wales, Scotland, Poland,

Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Ottoman

Empire, Ukraine, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Norway, Belgium, Luxembourg,

the Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, Bulgaria, Armenia, Greece,

Lithuania, Estonia, Latvia, Syria, Lebanon and several other regions.

Italian population in Argentina arrived mainly from the northern Italian regions varying between Piedmont, Veneto and Lombardy, later from Campania and Calabria;

Many Argentines have the gentilic of an Italian city, place, street or

occupation of the immigrant as last name, many of them were not

necessarily born Italians, but once they did the roles of immigration

from Italy the name usually changed. Spanish immigrants were mainly Galicians and Basques. Millions of immigrants also came from France (notably Béarn and the Northern Basque Country), Germany, Switzerland, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Ireland, Greece, Portugal, Finland, Russia and the United Kingdom. The Welsh settlement in Patagonia, known as Y Wladfa, began in 1865; mainly along the coast of Chubut Province. In addition to the main colony in Chubut, a smaller colony was set up in Santa Fe and another group settled at Coronel Suárez, southern Buenos Aires Province. Of the 50,000 Patagonians of Welsh descent, about 5,000 are Welsh speakers. The community is centered on the cities of Gaiman, Trelew and Trevelin.

Brazil

Brazil has long been a melting pot for a wide range of cultures. From colonial times Portuguese Brazilians

have favoured assimilation and tolerance for other peoples, and

intermarriage was more acceptable in Brazil than in most other European

colonies. However, Brazilian society has never been completely free of

ethnic strife and exploitation, and some groups have chosen to remain

separate from mainstream social life. Brazilians of mainly European

descent (Portuguese, German, French, Italian, Austrian, Polish, Spanish,

Hungarian, Lithuanian, Ukrainian, Russian, etc.) account for more than

half the population, although people of mixed ethnic backgrounds form an

increasingly larger segment; roughly two-fifths of the total are

mulattoes (mulattos; people of mixed African and European ancestry) and mestizos (mestiços, or caboclos;

people of mixed European and Indian ancestry). Portuguese are the main

European ethnic group in Brazil, and most Brazilians can trace their

ancestry to an ethnic Portuguese or a mixed-race Portuguese. Among European descendants, Brazil has the largest Italian diaspora, the second largest German diaspora, as well as other European groups. The country is also home to the largest Japanese diaspora outside Japan, the largest Arab community outside the Arab World, the largest African diaspora outside Africa and one of the top 10 Jewish populations.

Chile

In the 16th and 17th century Central Chile was a melting pot for uprooted indigenous peoples and it has been argued that Mapuche, Quechua and Spanish languages coexisted there, with significant bilingualism, during the 17th century. This coexistence explains how Quechua became the indigenous language that has influenced Chilean Spanish the most. Besides Araucanian

Mapuche and Quechua speaking populations a wide array of disparate

indigenous peoples were exported to Central Chile by the Spanish for

example peoples from Chiloé Archipelago, Huarpes from the arid areas across the Andes, and likely also some Chonos from the Patagonian archipelagoes.

South of Central Chile, in the Spanish exclave of Valdivia people of Spanish, Mapuche and Afro-Peruvian descendance lived together in colonial times. Once Spanish presence in Valdivia was reestablished in 1645, authorities had convicts from all-over the Viceroyalty of Peru construct the Valdivian Fort System. The convicts, many of whom were Afro-Peruvians, became soldier-settlers once they had served their term. Close contacts with indigenous Mapuche meant many soldiers were bilingual in Spanish and Mapuche. A 1749 census in Valdivia shows that Afro-descendants had a strong presence in the area.

Colombia

Colombia

is a melting pot of races and ethnicities. The population is descended

from three racial groups—Native Americans, blacks, and whites—that have

mingled throughout the nearly 500 years of the country's history. No

official figures were available, since the Colombian government dropped

any references to race in the census after 1918, but according to rough

estimates in the late 1980s, mestizos (white and Native American mix)

constituted approximately 50% of the population, whites (predominantly

Spanish origin, Italian, German, French, etc.) made 25%, mulattoes

(black-white mix) 14% and zambos (black and Native American mix) 4%,

blacks (pure or predominantly of African origin) 3%, and Native

Americans 1%.

Costa Rica

Costa Rican

people is a very syncretic melting pot, because the country has been

constituted in percentage since the 16th century by immigrants from all

the European countries—mostly Spaniards and Italians with a lot of Germans, British, Swedes, Swiss, French and Croats—also as black people from Africa and Jamaica, Americans, Chinese, Lebanese and Latin Americans

who have intermingled and married over time with the large native

populations (criollos, castizos, mulattos, blacks and tri-racial)

creating the national average modern ethnic composition.

Nowadays a great part of the Costa Rican inhabitants are

considered white and mestizo(84%), with minority groups of mulatto (7%),

indigenous (2%), Chinese (2%) and black (1%). Also, over 9% of the

total population is foreign-born (specially from Nicaragua, Colombia and the United States).

Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent has a long history of inter-ethnic marriage dating back to ancient India. Various groups of people have been intermarrying for millennia in the Indian subcontinent, including speakers of Dravidian, Indo-Aryan, Austroasiatic, and Tibeto-Burman

languages. On account of such diverse influences, the Indian

subcontinent in a nut-shell appears to be a cradle of human

civilization. Despite invasions in its recent history it has succeeded

in organically assimilating incoming influences, blunting their wills

for imperialistic hegemony and maintaining its strong roots and culture.

These invasions, however, brought their own racial mixing between

diverse populations and the Indian subcontinent is considered an

exemplary "melting pot" (and not a "salad bowl") by many geneticists for

exactly this reason. However, society in the Indian subcontinent has

never been completely free of ethnic strife and exploitation, and some

groups have chosen to remain separate from mainstream social life.

Ethnic conflicts in Pakistan and India between various ethnic and religious groups are an example of this.

Afghanistan

Afghanistan

seems to be in the process of becoming a melting pot, as customs

specific to particular ethnic groups are becoming summarily perceived as

national traits of Afghanistan. The term Afghan was originally used to refer to the Pashtuns in the Middle Ages, and the intention behind the creation of the Afghan state was originally to be a Pashtun state,

but later this policy changed, leading to the inclusion of non-Pashtuns

in the state as Afghans. Today in Afghanistan, the development of a

cultural melting pot is occurring, where different Afghanistan ethnic

groups are mixing together to build a new Afghan ethnicity composed of

preceding ethnicities in Afghanistan today, ultimately replacing the old

Pashtun identity which stood for Afghan. With the churning growth of Persian,

many ethnic groups, including de-tribalized Pashtuns, are adopting Dari

Persian as their new native tongue. Many ethnic groups in Afghanistan

tolerate each other, while the Hazara–Pashtun conflict was notable, and often claimed as a Shia-Sunni conflict instead of ethnic conflict, as this conflict was carried out by the Taliban. The Taliban, which are mostly ethnically Pashtun, have spurred Anti-Pashtunism across non-Pashtun Afghans. Pashtun–Tajik

rivalries have lingered about, but are much milder. Reasons for this

antipathy are criticism of Tajiks (for either their non-tribal culture

or cultural rivalry in Afghanistan) by Pashtuns and criticism of Taliban

(mostly composed of Pashtuns) by Tajiks. There have been rivalries

between Pashtuns and Uzbeks as well, which is likely very similar to the Kyrgyzstan Crisis, which Pashtuns would likely take place as Kyrgyz (for having a similar nomadic culture), rivaling with Tajiks and Uzbeks (of sedentary culture), despite all being Sunni Muslims.

Israel

In the early years of the state of Israel, the term melting pot

(כור היתוך), also known as "Ingathering of the Exiles" (קיבוץ גלויות),

was not a description of a process, but an official governmental

doctrine of assimilating the Jewish immigrants that originally came from

varying cultures (see Jewish ethnic divisions).

This was performed on several levels, such as educating the younger

generation (with the parents not having the final say) and (to mention

an anecdotal one) encouraging and sometimes forcing the new citizens to

adopt a Hebrew name.

Activists such as the Iraq-born Ella Shohat that an elite which developed in the early 20th century, out of the earlier-arrived Zionist Pioneers of the Second and Third Aliyas (immigration waves)—and who gained a dominant position in the Yishuv (pre-state community) since the 1930s—had formulated a new Hebrew culture, based on the values of Socialist Zionism, and imposed it on all later arrivals, at the cost of suppressing and erasing these later immigrants' original culture.

Proponents of the Melting Pot policy asserted that it applied to all newcomers to Israel equally; specifically, that Eastern European Jews were pressured to discard their Yiddish-based culture as ruthlessly as Mizrahi

Jews were pressured to give up the culture which they developed during

centuries of life in Arab and Muslim countries. Critics respond,

however, that a cultural change effected by a struggle within the Ashkenazi-East

European community, with younger people voluntarily discarding their

ancestral culture and formulating a new one, is not parallel to the

subsequent exporting and imposing of this new culture on others, who had

no part in formulating it. Also, it was asserted that extirpating the

Yiddish culture had been in itself an act of oppression only compounding

what was done to the Mizrahi immigrants.

Today the reaction to this doctrine is ambivalent; some say that

it was a necessary measure in the founding years, while others claim

that it amounted to cultural oppression.

Others argue that the melting pot policy did not achieve its declared

target: for example, the persons born in Israel are more similar from an

economic point of view to their parents than to the rest of the

population.

The policy is generally not practised today though as there is less

need for that—the mass immigration waves at Israel's founding have

declined. Nevertheless, one fifth of current Israel's Jewish population

have immigrated from former Soviet Union in the last two decades. The Jewish population includes other minorities such as Haredi Jews; Furthermore, 20% of Israel's population is Arab. These factors as well as others contribute to the rise of pluralism as a common principle in the last years.

Russia

Already the Kievan Rus was a multi ethnic state where different ethnicities merged, including Slavs, Finns, Turks and Balts.

Later the expansion of the Grand Duchy of Moscow and later of the Russian Empire throughout 15th to 20th centuries created a unique melting pot. Though the majority of Russians had Slavic-speaking ancestry, different ethnicities were assimilated into the Russian melting pot through the period of expansion. Assimilation

was a way for ethnic minorities to advance their standing within the

Russian society and state—as individuals or groups. It required adoption

of Russian as a day-to-day language and Orthodox Christianity

as religion of choice. The Roman Catholics (as in Poland and Lithuania)

generally resisted assimilation. Throughout the centuries of eastward

expansion of Russia, Finnic and Turkic peoples were assimilated and included into the emerging Russian nation. This includes Mordvin, Udmurt, Mari, Tatar, Chuvash, Bashkir, and others. Surnames of many of Russia's nobility (including Suvorov, Kutuzov, Yusupov, etc.) suggest their Turkic origin. Groups of later, 18th- and 19th-century migrants to Russia, from Europe (Germans, French, Italians, Poles, Serbs, Bulgarians, Greeks, Jews, etc.) or the Caucasus (Georgians, Armenians, Ossetians, Chechens, Azeris and Turks among them) also assimilated within several generations after settling among Russians in the expanding Russian Empire.

Soviet Union

The Soviet people (Russian: Советский народ) was an ideological epithet for the population of the Soviet Union. The Soviet government promoted the doctrine of assimilating all peoples living in USSR into one Soviet people, accordingly to Marxist principle of fraternity of peoples.

Southeast Asia

The term has been used to describe a number of countries in Southeast Asia.

Given the region's location and importance to trade routes between

China and the Western world, certain countries in the region have become

ethnically diverse.

In Vietnam, a relevant phenomenon is "tam giáo đồng nguyên", meaning

the co-existence and co-influence of three major religious teaching

schools (Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism), which shows a process

defined as "cultural addivity".

Philippines

In

the pre-Spanish era the Philippines was the trading nexus of various

cultures and eventually became the melting pot of different nations.

This primarily consisted of the Chinese, Indian and Arab traders. This

is also includes neighboring southeast Asian cultures. The cultures and

races mixed with indigenous tribes, mainly of Austronesian descent (i.e.

the Indonesians, Malays and Brunei) and the Negritos.

The result was a mix of cultures and ideals. This melting pot of

culture continued with the arrival of Europeans, mixing their western

culture with the nation. The Spanish Empire

colonized the Philippines for more than three centuries, and during the

early 20th century, was conquered and annexed by the United States and

occupied by the Empire of Japan during World War II.

In modern times, the Philippines has been the place of many retired

Americans, Japanese expatriates and Korean students. And continues to

uphold its status as a melting pot state today.

In popular culture

- Animated educational series Schoolhouse Rock! has a song entitled "The Great American Melting Pot".

- In 1969 the song "Melting Pot" was released by the UK band Blue Mink and charted at #3 in the UK Singles Chart.

The lyrics espouse how the world should become one big melting pot

where different races and religions are to be mixed, "churning out

coffee coloured people by the score", referring to the possible

pigmentation of children after such racial mixing.

- On The Colbert Report, an alternative to the melting pot culture was posed on The Wørd called "Lunchables", where separate cultures "co-exist" by being entirely separate and maintaining no contact or involvement (see also NIMBY).

- In a 2016 first-person shooter video game DOOM, a hologram

of a demon-worshipping spokesperson of the UAC company has several

lines, amongst which is "Earth is the melting pot of the universe",

aiming to make demons seem more sympathetic.

Quotations

Man

is the most composite of all creatures.... Well, as in the old burning

of the Temple at Corinth, by the melting and intermixture of silver and

gold and other metals a new compound more precious than any, called Corinthian brass,

was formed; so in this continent—asylum of all nations—the energy of

Irish, Germans, Swedes, Poles, and Cossacks, and all the European

tribes—of the Africans, and of the Polynesians—will construct a new

race, a new religion, a new state, a new literature, which will be as

vigorous as the new Europe which came out of the smelting-pot of the

Dark Ages, or that which earlier emerged from the Pelasgic and Etruscan

barbarism.

—

Ralph Waldo Emerson, journal entry, 1845, first published 1912 in Journals of Ralph Waldo Emerson with Annotations, Vol. IIV, 116

These good people are future

'Yankees.' By next year they will be wearing the clothes of their new

country, and by the following year they will be speaking its language.

Their children will grow up and will no longer even remember the mother

country. America is the melting pot in which all the nations of the

world come to be fused into a single mass and cast in a uniform mold.

— Ernest

Duvergier de Hauranne, English translation entitled “A Frenchman in

Lincoln’s America” [Volume 1] (Lakewood Classics, 1974), 240-41, of

“Huit Mois en Amérique: Lettres et Notes de Voyage, 1864-1865” (1866).

No reverberatory effect of The Great War

has caused American public opinion more solicitude than the failure of

the 'melting-pot.' The discovery of diverse nationalistic feelings among

our great alien population has come to most people as an intense shock.

—

Randolph Bourne, "Trans-National America", in Atlantic Monthly, 118 (July 1916), 86–97

Blacks, Chinese, Puerto Ricans,

etcetera, could not melt into the pot. They could be used as wood to

produce the fire for the pot, but they could not be used as material to

be melted into the pot.