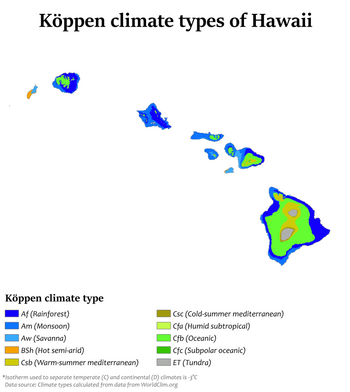

Köppen climate types of Hawaii

The American state of Hawaii, which covers the Hawaiian Islands, is tropical but it experiences many different climates, depending on altitude and surrounding. The island of Hawaii for example hosts 4 (out of 5 in total) climate groups on a surface as small as 4,028 square miles (10,430 km2) according to the Köppen climate types: tropical, arid, temperate and polar. When counting also the Köppen sub-categories the island of Hawaii hosts 10 (out of 14 in total) climate zones. The islands receive most rainfall from the trade winds on their north and east flanks (the windward side) as a result of orographic precipitation. Coastal areas are drier, especially the south and west side or leeward sides.

The Hawaiian Islands receive most of their precipitation from

October to April. Drier conditions generally prevail from May to

September. Due to cooler waters around Hawaii, the risk of tropical cyclones is low for Hawai'i.

Temperature

Temperatures

at sea level generally range from highs of 84–88 °F (29–31 °C) during

the summer months to 79–83 °F (26–28 °C) during the winter months.

Rarely does the temperature rise above 90 °F (32 °C) or drop below 60 °F

(16 °C) at lower elevations. Temperatures are lower at higher

altitudes. During the winter, snowfall is common at the summits of Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa on Hawaii Island. On Maui, the summit of Haleakalā

occasionally experiences snowfall, but snow had never been observed

below 7,500 feet (2,300 m) before February 2019, when snow was observed

at 6,200 feet (1,900 m) and fell at higher elevations in amounts large

enough to force Haleakalā National Park to close for several days. The record low temperature in Honolulu is 52 °F (11 °C) on January 20, 1969.

Temperatures of 90 °F (32 °C) and above are uncommon (with the

exception of dry, leeward areas). In the leeward areas, temperatures may

reach into the low 90s several days during the year, but temperatures

higher than these are unusual. The highest temperature ever recorded on

the islands was 100 °F (38 °C) on April 27, 1931 in Pahala.

The surface waters of the open ocean around Hawaii range from 75 °F

(24 °C) between late February and early April, to a maximum of 82 °F

(28 °C) in late September or early October. In the United States, only Florida has warmer surf temperatures.

The Pacific High, and with it the trade-wind zone, moves north

and south with changing angle of the sun, so that it reaches its

northernmost position in the summer. This brings trade winds during the

period of May through September, when they are prevalent 80 to 95

percent of the time. From October through April, the heart of the trade

winds moves south of Hawaii; thus there average wind speeds are lower

across the islands. Due to Hawaii being at the northern edge of the

tropics (mostly above 20 latitude), there are only weak wet and dry

seasons unlike many tropical climates.

Winds

Island wind

patterns are very complex. Though the trade winds are fairly constant,

their relatively uniform air flow is distorted and disrupted by

mountains, hills, and valleys. Usually winds blow upslope by day and

downslope by night. Local conditions that produce occasional violent

winds are not well understood. These are very localized, sometimes

reaching speeds of 60 to 100 mph (100 to 160 km/h) and are best known in

the settled areas of Kula and Lahaina on Maui. The Kula winds are strong downslope winds on the lower slopes of the west side of Haleakala. These winds tend to be strongest from 2,000 to 4,000 ft (600 to 1,200 m) above mean sea level.

The Lahaina winds are also downslope winds, but are somewhat different. They are also called "lehua winds" after the ʻōhiʻa lehua (Metrosideros polymorpha),

whose red blossoms fill the air when these strong winds blow. They

issue from canyons at the base of the western Maui mountains, where

steeper canyon slopes meet the more gentle piedmont

slope below. These winds only occur every 8 to 12 years. They are

extremely violent, with wind speeds of 80–100 mph (130–160 km/h) or

more.

Cloud formation

Under trade wind

conditions, there is very often a pronounced moisture discontinuity

between 4,000 and 8,000 feet (1,200 and 2,400 m). Below these heights,

the air is moist; above, it is dry. The break (a large-scale feature of

the Pacific High) is caused by a temperature inversion embedded in the

moving trade wind air. The inversion tends to suppress the vertical

movement of air and so restricts cloud development to the zone just

below the inversion. The inversion is present 50 to 70 percent of the

time; its height fluctuates from day to day, but it is usually between

5,000 and 7,000 feet (1,500 and 2,100 m). On trade wind days when the

inversion is well defined, the clouds develop below these heights with

only an occasional cloud top breaking through the inversion.

These towering clouds form along the mountains where the incoming

trade wind air converges as it moves up a valley and is forced up and

over the mountains to heights of several thousand feet. On days without

an inversion, the sky is almost cloudless (completely cloudless skies

are extremely rare). In leeward areas well screened from the trade winds

(such as the west coast of Maui), skies are clear 30 to 60 percent of

the time.

Windward areas tend to be cloudier during the summer, when the

trade winds and associated clouds are more prevalent, while leeward

areas, which are less affected by cloudy conditions associated with

trade wind cloudiness, tend to be cloudier during the winter, when storm

fronts pass through more frequently. On Maui, the cloudiest zones are

at and just below the summits of the mountains, and at elevations of

2,000 to 4,000 ft (600 to 1,200 m) on the windward sides of Haleakala.

In these locations the sky is cloudy more than 70 percent of the time.

The usual clarity of the air in the high mountains is associated with

the low moisture content of the air.

Precipitation

Hawaii

differs from many tropical locations with pronounced wet and dry

seasons, in that the wet season coincides with the winter months (rather

than the summer months more typical of other places in the tropics).

For instance, Honolulu's Köppen climate classification is the rare As wet-winter subcategory of the Tropical wet and dry climate type.

Major storms occur most frequently in October through March.

There may be as many as six or seven major storm events in a year. Such

storms bring heavy rains and can be accompanied by strong local winds.

The storms may be associated with the passage of a cold front, the leading edge of a mass of relatively cool air that is moving from west to east or from northwest to southeast.

Annual mean rainfall ranges from 188 mm (7.4 inches) on the summit of Mauna Kea to 10,271 mm (404 inches) in Big Bog. Windward slopes have greater rainfall than leeward lowlands and tall mountains.

Average Annual Rainfall for the State of Hawai‘i, http://rainfall.geography.hawaii.edu/

On windward coasts, many brief showers are common, not one of which

is heavy enough to produce more than 0.01 in (0.25 mm) of rain. The

usual run of trade wind weather yields many light showers in the

lowlands, whereas torrential rains are associated with a sudden surge in

the trade winds or with a major storm. Hana has had as much as 28 in (710 mm) of rain in a single 24-hour period.

Severe thunderstorms, as defined by the National Weather Service (NWS) as tornadoes, hail 1 in (25 mm) or larger, and/or convective winds of at least 58 mph (93 km/h) occur but are relatively uncommon. Nontornadic waterspouts are more common than tornadoes produced by supercells,

which produce stronger, longer lasting tornadoes, especially with

respect to inland areas, and also produce the largest hail, such as the 2012 Hawaii hailstorm. An annual average of approximately one tornado, either emanating from supercells or by other processes, occurs.

Kona storms

are features of the winter season. The name comes from winds out of the

"kona" or usually leeward direction. Rainfall in a well-developed Kona

storm is widespread and more prolonged than in the usual cold-front

storm. Kona storm rains are usually most intense in an arc, extending

from south to east of the storm and well in advance of its center. Kona

rains last from several hours to several days. The rains may continue

steadily, but the longer lasting ones are characteristically interrupted

by intervals of lighter rain or partial clearing, as well as by intense

showers superimposed on the more moderate continuous, steady rain. An

entire winter may pass without a single well-developed Kona storm. More

often there are one or two such storms a year; sometimes four or five.

Hurricanes

The hurricane

season in the Hawaiian Islands is roughly from June through November,

when hurricanes and tropical storms are most probable in the North

Pacific. These storms tend to originate off the coast of Mexico (particularly the Baja California peninsula)

and track west or northwest towards the islands. As storms cross the

Pacific, they tend to lose strength if they bear northward and encounter

cooler water.

True hurricanes are rare in Hawai'i, thanks in part to the

comparatively cool waters around the islands as well as unfavorable

atmospheric conditions, such as enhanced wind shear; only four have

affected the islands during 63 years.

Tropical storms are more frequent. These have more modest winds, below

74 mph (119 km/h). Because tropical storms resemble Kona storms, and

because early records do not distinguish clearly between them, it has

been difficult to estimate the average frequency of tropical storms.

Every year or two a tropical storm will affect the weather in some part

of the islands. Unlike cold fronts

and Kona storms, hurricanes and tropical storms are most likely to

occur during the last half of the year, from July through December.

Three strong and destructive hurricanes are known to have made landfall

on the islands, an unnamed storm in 1871, Hurricane Dot in 1959, and Hurricane Iniki in 1992. Another hurricane, Iwa,

caused significant damage in 1982 but its center passed nearby and did

not directly make landfall. The rarity of hurricanes making landfall on

the Islands is subject to change as the climate warms. In the Pliocene

era, where CO2 levels were comparable to those we see today, the waters

around Hawai'i were much warmer, resulting in frequent hurricane strikes

in computer simulations.

Effect on trade winds

A

true-color satellite view of Hawaii shows that most of the flora on the

islands grow on the north-east sides, which face the trade winds. The

texture change around the calmer south-west of the islands is the result

of the shelter provided from the islands.

The top image above shows the winds around the Hawaiian Islands measured by the Seawinds instrument aboard QuikSCAT

during August 1999. Trade winds blow from right to left in the image.

The bottom image shows the ocean current formed by the islands’ wake.

Arrows indicate current direction and speed, while white contours show

ocean temperatures. The warm water of the current generates winds that

sustain the current for thousands of miles.

Despite being small islands within the vast Pacific Ocean, the

Hawaiian Islands have a surprising effect on ocean currents and

circulation patterns over much of the Pacific. In the Northern

Hemisphere, trade winds blow from northeast to southwest, from North and

South America toward Asia, between the equator and 30 degrees north latitude. Typically, the trade winds continue across the Pacific — unless something gets in their way, like an island.

Hawai‘i's high mountains present a substantial obstacle to the

trade winds. The elevated topography blocks the airflow, effectively

splitting the trade winds in two. This split causes a zone of weak

winds, called a "wind wake", on the leeward side of the islands.

Aerodynamic theory

indicates that an island wind wake effect should dissipate within a few

hundred kilometers and not be felt in the western Pacific. However, the

wind wake caused by the Hawaiian Islands extends 1,860 miles

(3,000 km), roughly 10 times longer than any other wake. The long wake

testifies to the strong interaction between the atmosphere and ocean,

which has strong implications for global climate research. It is also

important for understanding natural climate variations, like El Niño.

There are number of reasons why this has been observed only in

Hawai‘i. First, the ocean reacts slowly to fast-changing winds; winds

must be steady to exert force on the ocean, such as the trade winds.

Second, the high mountain topography provides a significant disturbance

to the winds. Third, the Hawaiian Islands are large in horizontal

(east-west) scale, extending over four degrees in longitude. It is this

active interaction between wind, ocean current, and temperature that

creates this uniquely long wake west of Hawaii.

The wind wake drives an eastward "counter current" that brings

warm water 5,000 miles (8,000 km) from the Asian coast. This warm water

drives further changes in wind, allowing the island effect to extend far

into the western Pacific. The counter current had been observed by oceanographers near the Hawaiian Islands years before the long wake was discovered, but they did not know what caused it.