From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The expansion of the universe is the increase of the distance between two distant parts of the universe with time.[1] It is an intrinsic expansion whereby the scale of space itself changes. The universe does not expand "into" anything and does not require space to exist "outside" it. Technically neither space, nor objects in space, move. Instead it is the metric governing the size and geometry of spacetime itself that changes in scale. Although light and objects within spacetime cannot travel faster than the speed of light, this limitation does not restrict the metric itself. To an observer it appears that space is expanding and all but the nearest galaxies are receding into the distance.

During the inflationary epoch about 10−32 of a second after the Big Bang, the universe suddenly expanded, and its volume increased by a factor of at least 1078 (an expansion of distance by a factor of at least 1026 in each of the three dimensions), equivalent to expanding an object 1 nanometer (10−9 m, about half the width of a molecule of DNA) in length to one approximately 10.6 light years (about 1017 m or 62 trillion miles) long. A much slower and gradual expansion of space continued after this, until at around 9.8 billion years after the Big Bang (4 billion years ago) it began to gradually expand more quickly, and is still doing so today.

The metric expansion of space is a completely different kind of expansion than the expansions and explosions seen in daily life. It also seems to be a property of the entire universe as a whole rather than a phenomenon that applies just to one part of the universe or can be observed from "outside" it.

Metric expansion is a key feature of Big Bang cosmology, is modeled mathematically with the Friedmann-Lemaître-Robertson-Walker metric and is a generic property of the universe we inhabit. However, the model is valid only on large scales (roughly the scale of galaxy clusters and above), because gravitational attraction binds matter together strongly enough that metric expansion cannot be observed at this time, on a smaller scale. As such, the only galaxies receding from one another as a result of metric expansion are those separated by cosmologically relevant scales larger than the length scales associated with the gravitational collapse that are possible in the age of the universe given the matter density and average expansion rate.

Physicists have postulated the existence of dark energy, appearing as a cosmological constant in the simplest gravitational models as a way to explain the acceleration. According to the simplest extrapolation of the currently-favored cosmological model, the Lambda-CDM model, this acceleration becomes more dominant into the future. In June 2016, NASA and ESA scientists reported that the universe was found to be expanding 5% to 9% faster than thought earlier, based on studies using the Hubble Space Telescope.[2]

While special relativity prohibits objects from moving faster than light with respect to a local reference frame where spacetime can be treated as flat and unchanging, it does not apply to situations where spacetime curvature or evolution in time become important. These situations are described by general relativity, which allows the separation between two distant objects to increase faster than the speed of light, although the definition of "separation" is different from that used in an inertial frame. This can be seen when observing distant galaxies more than the Hubble radius away from us (approximately 4.5 gigaparsecs or 14.7 billion light-years); these galaxies have a recession speed that is faster than the speed of light. Light that is emitted today from galaxies beyond the cosmological event horizon, about 5 gigaparsecs or 16 billion light-years, will never reach us, although we can still see the light that these galaxies emitted in the past. Because of the high rate of expansion, it is also possible for a distance between two objects to be greater than the value calculated by multiplying the speed of light by the age of the universe. These details are a frequent source of confusion among amateurs and even professional physicists.[3] Due to the non-intuitive nature of the subject and what has been described by some as "careless" choices of wording, certain descriptions of the metric expansion of space and the misconceptions to which such descriptions can lead are an ongoing subject of discussion within education and communication of scientific concepts.[4][5][6][7]

The expansion of the universe is the increase of the distance between two distant parts of the universe with time.[1] It is an intrinsic expansion whereby the scale of space itself changes. The universe does not expand "into" anything and does not require space to exist "outside" it. Technically neither space, nor objects in space, move. Instead it is the metric governing the size and geometry of spacetime itself that changes in scale. Although light and objects within spacetime cannot travel faster than the speed of light, this limitation does not restrict the metric itself. To an observer it appears that space is expanding and all but the nearest galaxies are receding into the distance.

During the inflationary epoch about 10−32 of a second after the Big Bang, the universe suddenly expanded, and its volume increased by a factor of at least 1078 (an expansion of distance by a factor of at least 1026 in each of the three dimensions), equivalent to expanding an object 1 nanometer (10−9 m, about half the width of a molecule of DNA) in length to one approximately 10.6 light years (about 1017 m or 62 trillion miles) long. A much slower and gradual expansion of space continued after this, until at around 9.8 billion years after the Big Bang (4 billion years ago) it began to gradually expand more quickly, and is still doing so today.

The metric expansion of space is a completely different kind of expansion than the expansions and explosions seen in daily life. It also seems to be a property of the entire universe as a whole rather than a phenomenon that applies just to one part of the universe or can be observed from "outside" it.

Metric expansion is a key feature of Big Bang cosmology, is modeled mathematically with the Friedmann-Lemaître-Robertson-Walker metric and is a generic property of the universe we inhabit. However, the model is valid only on large scales (roughly the scale of galaxy clusters and above), because gravitational attraction binds matter together strongly enough that metric expansion cannot be observed at this time, on a smaller scale. As such, the only galaxies receding from one another as a result of metric expansion are those separated by cosmologically relevant scales larger than the length scales associated with the gravitational collapse that are possible in the age of the universe given the matter density and average expansion rate.

Physicists have postulated the existence of dark energy, appearing as a cosmological constant in the simplest gravitational models as a way to explain the acceleration. According to the simplest extrapolation of the currently-favored cosmological model, the Lambda-CDM model, this acceleration becomes more dominant into the future. In June 2016, NASA and ESA scientists reported that the universe was found to be expanding 5% to 9% faster than thought earlier, based on studies using the Hubble Space Telescope.[2]

While special relativity prohibits objects from moving faster than light with respect to a local reference frame where spacetime can be treated as flat and unchanging, it does not apply to situations where spacetime curvature or evolution in time become important. These situations are described by general relativity, which allows the separation between two distant objects to increase faster than the speed of light, although the definition of "separation" is different from that used in an inertial frame. This can be seen when observing distant galaxies more than the Hubble radius away from us (approximately 4.5 gigaparsecs or 14.7 billion light-years); these galaxies have a recession speed that is faster than the speed of light. Light that is emitted today from galaxies beyond the cosmological event horizon, about 5 gigaparsecs or 16 billion light-years, will never reach us, although we can still see the light that these galaxies emitted in the past. Because of the high rate of expansion, it is also possible for a distance between two objects to be greater than the value calculated by multiplying the speed of light by the age of the universe. These details are a frequent source of confusion among amateurs and even professional physicists.[3] Due to the non-intuitive nature of the subject and what has been described by some as "careless" choices of wording, certain descriptions of the metric expansion of space and the misconceptions to which such descriptions can lead are an ongoing subject of discussion within education and communication of scientific concepts.[4][5][6][7]

Cosmic inflation

Around 1930, Edwin Hubble discovered that light from remote galaxies was redshifted; i.e. the more remote galaxies were, the more shifted was the light coming from them. This observation was quickly interpreted as galaxies being receding from earth. If earth is not in some special, privileged, central position in the universe, then it would mean all galaxies are moving apart, and the further away, the faster they are moving away. It is now understood that the universe is expanding, carrying the galaxies with it, and causing this observation. Many other observations agree, and also lead to the same conclusion. However, for many years it was not clear why or how the universe might be expanding, or what it might signify.Based on a huge amount of experimental observation and theoretical work, it is now believed that the reason for the observation is that space itself is expanding, and that it expanded very rapidly within the first fraction of a second after the Big Bang. This kind of expansion is known as the "metric expansion". In mathematics and physics, a "metric" means a measure of distance, and the term implies that the sense of distance within the universe is itself changing, although at this time it is far too small an effect to see on less than an intergalactic scale.

The modern explanation for the metric expansion of space was proposed by physicist Alan Guth in 1979, while investigating the problem of why no magnetic monopoles are seen today. Guth found in his investigation that if the universe contained a field that has a positive-energy false vacuum state, then according to general relativity it would generate an exponential expansion of space. It was very quickly realized that such an expansion would resolve many other long-standing problems. These problems arise from the observation that to look like it does today, the universe would have to have started from very finely tuned, or "special" initial conditions at the Big Bang. Inflation theory largely resolves these problems as well, thus making a universe like ours much more likely in the context of Big Bang theory.

No field responsible for the cosmic inflation has been discovered. However such a field, if found in the future, would be scalar. The first similar scalar field proven to exist was only discovered in 2012 - 2013 and is still being researched. So it is not seen as problematic that a field responsible for cosmic inflation and the metric expansion of space has not yet been discovered.

The proposed field and its quanta (the subatomic particles related to it) have been named inflaton. If this field did not exist, scientists would have to propose a different explanation for all the observations that strongly suggest a metric expansion of space has occurred, and is still occurring much more slowly today.

Overview of metrics and comoving coordinates

To understand the metric expansion of the universe, it is helpful to discuss briefly what a metric is, and how metric expansion works.A metric defines the concept of distance, by stating in mathematical terms how distances between two nearby points in space are measured, in terms of the coordinate system. Coordinate systems locate points in a space (of whatever number of dimensions) by assigning unique positions on a grid, known as coordinates, to each point. GPS, latitude and longitude, and x-y graphs are common examples of coordinates. A metric is a formula which describes how a number known as "distance" is to be measured between two points.

It may seem obvious that distance is measured by a straight line, but in many cases it is not. For example, long haul aircraft travel along a curve known as a "great circle" and not a straight line, because that is a better metric for air travel. (A straight line would go through the earth). Another example is planning a car journey, where one might want the shortest journey in terms of travel time - in that case a straight line is a poor choice of metric because the shortest distance by road is not normally a straight line. A final example is the internet, where even for nearby towns, the quickest route for data can be via major connections that go across the country and back again. In this case the metric used will be the shortest time that data takes to travel between two points on the network.

In cosmology, we cannot use a ruler to measure metric expansion, because our ruler will also be expanding (extremely slowly). Also any objects on or near earth that we might measure are being held together or pushed apart by several forces which are far larger in their effects. So even if we could measure the tiny expansion that is still happening, we would not notice the change on a small scale or in everyday life. On a large intergalactic scale, we can use other tests of distance and these do show that space is expanding, even if a ruler on earth could not measure it.

The metric expansion of space is described using the mathematics of metric tensors. The coordinate system we use is called "comoving coordinates", a type of coordinate system which takes account of time as well as space and the speed of light, and allows us to incorporate the effects of both general and special relativity.

Example: "Great Circle" metric for Earth's surface

For example, consider the measurement of distance between two places on the surface of the Earth. This is a simple, familiar example of spherical geometry. Because the surface of the Earth is two-dimensional, points on the surface of the Earth can be specified by two coordinates — for example, the latitude and longitude. Specification of a metric requires that one first specify the coordinates used. In our simple example of the surface of the Earth, we could choose any kind of coordinate system we wish, for example latitude and longitude, or X-Y-Z Cartesian coordinates. Once we have chosen a specific coordinate system, the numerical values of the coordinates of any two points are uniquely determined, and based upon the properties of the space being discussed, the appropriate metric is mathematically established too. On the curved surface of the Earth, we can see this effect in long-haul airline flights where the distance between two points is measured based upon a great circle, rather than the straight line one might plot on a two-dimensional map of the Earth's surface. In general, such shortest-distance paths are called "geodesics". In Euclidean geometry, the geodesic is a straight line, while in non-Euclidean geometry such as on the Earth's surface, this is not the case. Indeed, even the shortest-distance great circle path is always longer than the Euclidean straight line path which passes through the interior of the Earth. The difference between the straight line path and the shortest-distance great circle path is due to the curvature of the Earth's surface. While there is always an effect due to this curvature, at short distances the effect is small enough to be unnoticeable.On plane maps, great circles of the Earth are mostly not shown as straight lines. Indeed, there is a seldom-used map projection, namely the gnomonic projection, where all great circles are shown as straight lines, but in this projection, the distance scale varies very much in different areas. There is no map projection in which the distance between any two points on Earth, measured along the great circle geodesics, is directly proportional to their distance on the map; such accuracy is possible only with a globe.

Metric tensors

In differential geometry, the backbone mathematics for general relativity, a metric tensor can be defined which precisely characterizes the space being described by explaining the way distances should be measured in every possible direction. General relativity necessarily invokes a metric in four dimensions (one of time, three of space) because, in general, different reference frames will experience different intervals of time and space depending on the inertial frame. This means that the metric tensor in general relativity relates precisely how two events in spacetime are separated. A metric expansion occurs when the metric tensor changes with time (and, specifically, whenever the spatial part of the metric gets larger as time goes forward). This kind of expansion is different from all kinds of expansions and explosions commonly seen in nature in no small part because times and distances are not the same in all reference frames, but are instead subject to change. A useful visualization is to approach the subject rather than objects in a fixed "space" moving apart into "emptiness", as space itself growing between objects without any acceleration of the objects themselves. The space between objects grows or shrinks as the various geodesics converge or diverge.Because this expansion is caused by relative changes in the distance-defining metric, this expansion (and the resultant movement apart of objects) is not restricted by the speed of light upper bound of special relativity. Two reference frames that are globally separated can be moving apart faster than light without violating special relativity, although whenever two reference frames diverge from each other faster than the speed of light, there will be observable effects associated with such situations including the existence of various cosmological horizons.

Theory and observations suggest that very early in the history of the universe, there was an inflationary phase where the metric changed very rapidly, and that the remaining time-dependence of this metric is what we observe as the so-called Hubble expansion, the moving apart of all gravitationally unbound objects in the universe. The expanding universe is therefore a fundamental feature of the universe we inhabit — a universe fundamentally different from the static universe Albert Einstein first considered when he developed his gravitational theory.

Comoving coordinates

In expanding space, proper distances are dynamical quantities which change with time. An easy way to correct for this is to use comoving coordinates which remove this feature and allow for a characterization of different locations in the universe without having to characterize the physics associated with metric expansion. In comoving coordinates, the distances between all objects are fixed and the instantaneous dynamics of matter and light are determined by the normal physics of gravity and electromagnetic radiation. Any time-evolution however must be accounted for by taking into account the Hubble law expansion in the appropriate equations in addition to any other effects that may be operating (gravity, dark energy, or curvature, for example). Cosmological simulations that run through significant fractions of the universe's history therefore must include such effects in order to make applicable predictions for observational cosmology.Understanding the expansion of the universe

Measurement of expansion and change of rate of expansion

When an object is receding, its light gets stretched (redshifted). When the object is approaching, its light gets compressed (blueshifted).

In principle, the expansion of the universe could be measured by taking a standard ruler and measuring the distance between two cosmologically distant points, waiting a certain time, and then measuring the distance again, but in practice, standard rulers are not easy to find on cosmological scales and the timescales over which a measurable expansion would be visible are too great to be observable even by multiple generations of humans. The expansion of space is measured indirectly. The theory of relativity predicts phenomena associated with the expansion, notably the redshift-versus-distance relationship known as Hubble's Law; functional forms for cosmological distance measurements that differ from what would be expected if space were not expanding; and an observable change in the matter and energy density of the universe seen at different lookback times.

The first measurement of the expansion of space occurred with the creation of the Hubble diagram. Using standard candles with known intrinsic brightness, the expansion of the universe has been measured using redshift to derive Hubble's Constant: H0 = 67.15 ± 1.2 (km/s)/Mpc. For every million parsecs of distance from the observer, the rate of expansion increases by about 67 kilometers per second.[8][9][10]

The Hubble parameter is not thought to be constant through time. There are dynamical forces acting on the particles in the universe which affect the expansion rate. It was earlier expected that the Hubble parameter would be decreasing as time went on due to the influence of gravitational interactions in the universe, and thus there is an additional observable quantity in the universe called the deceleration parameter which cosmologists expected to be directly related to the matter density of the universe. Surprisingly, the deceleration parameter was measured by two different groups to be less than zero (actually, consistent with −1) which implied that today the Hubble parameter is converging to a constant value as time goes on. Some cosmologists have whimsically called the effect associated with the "accelerating universe" the "cosmic jerk".[11] The 2011 Nobel Prize in Physics was given for the discovery of this phenomenon.[12]

Measuring distances in expanding space

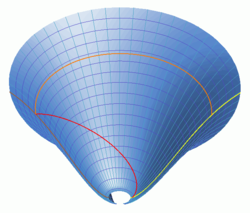

Two views of an isometric embedding of part of the visible universe over most of its history, showing how a light ray (red line) can travel an effective distance of 28 billion light years (orange line) in just 13 billion years of cosmological time.

At cosmological scales the present universe is geometrically flat,[13] which is to say that the rules of Euclidean geometry associated with Euclid's fifth postulate hold, though in the past spacetime could have been highly curved. In part to accommodate such different geometries, the expansion of the universe is inherently general relativistic; it cannot be modeled with special relativity alone, though such models exist, they are at fundamental odds with the observed interaction between matter and spacetime seen in our universe.

The images to the right show two views of spacetime diagrams that show the large-scale geometry of the universe according to the ΛCDM cosmological model. Two of the dimensions of space are omitted, leaving one dimension of space (the dimension that grows as the cone gets larger) and one of time (the dimension that proceeds "up" the cone's surface). The narrow circular end of the diagram corresponds to a cosmological time of 700 million years after the big bang while the wide end is a cosmological time of 18 billion years, where one can see the beginning of the accelerating expansion as a splaying outward of the spacetime, a feature which eventually dominates in this model. The purple grid lines mark off cosmological time at intervals of one billion years from the big bang. The cyan grid lines mark off comoving distance at intervals of one billion light years in the present era (less in the past and more in the future). Note that the circular curling of the surface is an artifact of the embedding with no physical significance and is done purely to make the illustration viewable; space does not actually curl around on itself. (A similar effect can be seen in the tubular shape of the pseudosphere.)

The brown line on the diagram is the worldline of the Earth (or, at earlier times, of the matter which condensed to form the Earth). The yellow line is the worldline of the most distant known quasar. The red line is the path of a light beam emitted by the quasar about 13 billion years ago and reaching the Earth in the present day. The orange line shows the present-day distance between the quasar and the Earth, about 28 billion light years, which is, notably, a larger distance than the age of the universe multiplied by the speed of light: ct.

According to the equivalence principle of general relativity, the rules of special relativity are locally valid in small regions of spacetime that are approximately flat. In particular, light always travels locally at the speed c; in our diagram, this means, according to the convention of constructing spacetime diagrams, that light beams always make an angle of 45° with the local grid lines. It does not follow, however, that light travels a distance ct in a time t, as the red worldline illustrates. While it always moves locally at c, its time in transit (about 13 billion years) is not related to the distance traveled in any simple way since the universe expands as the light beam traverses space and time. In fact the distance traveled is inherently ambiguous because of the changing scale of the universe. Nevertheless, we can single out two distances which appear to be physically meaningful: the distance between the Earth and the quasar when the light was emitted, and the distance between them in the present era (taking a slice of the cone along the dimension that we've declared to be the spatial dimension). The former distance is about 4 billion light years, much smaller than ct because the universe expanded as the light traveled the distance, the light had to "run against the treadmill" and therefore went farther than the initial separation between the Earth and the quasar. The latter distance (shown by the orange line) is about 28 billion light years, much larger than ct. If expansion could be instantaneously stopped today, it would take 28 billion years for light to travel between the Earth and the quasar while if the expansion had stopped at the earlier time, it would have taken only 4 billion years.

The light took much longer than 4 billion years to reach us though it was emitted from only 4 billion light years away, and, in fact, the light emitted towards the Earth was actually moving away from the Earth when it was first emitted, in the sense that the metric distance to the Earth increased with cosmological time for the first few billion years of its travel time, and also indicating that the expansion of space between the Earth and the quasar at the early time was faster than the speed of light. None of this surprising behavior originates from a special property of metric expansion, but simply from local principles of special relativity integrated over a curved surface.

Topology of expanding space

A graphical representation of the expansion of the universe with the

inflationary epoch represented as the dramatic expansion of the metric

seen on the left. This diagram can be confusing because the expansion

of space looks like it is happening into an empty "nothingness".

However, this is a choice made for convenience of visualization: it is

not a part of the physical models which describe the expansion.

Over time, the space that makes up the universe is expanding. The words 'space' and 'universe', sometimes used interchangeably, have distinct meanings in this context. Here 'space' is a mathematical concept that stands for the three-dimensional manifold into which our respective positions are embedded while 'universe' refers to everything that exists including the matter and energy in space, the extra-dimensions that may be wrapped up in various strings, and the time through which various events take place. The expansion of space is in reference to this 3-D manifold only; that is, the description involves no structures such as extra dimensions or an exterior universe.[14]

The ultimate topology of space is a posteriori — something which in principle must be observed — as there are no constraints that can simply be reasoned out (in other words there can not be any a priori constraints) on how the space in which we live is connected or whether it wraps around on itself as a compact space. Though certain cosmological models such as Gödel's universe even permit bizarre worldlines which intersect with themselves, ultimately the question as to whether we are in something like a "Pac-Man universe" where if traveling far enough in one direction would allow one to simply end up back in the same place like going all the way around the surface of a balloon (or a planet like the Earth) is an observational question which is constrained as measurable or non-measurable by the universe's global geometry. At present, observations are consistent with the universe being infinite in extent and simply connected, though we are limited in distinguishing between simple and more complicated proposals by cosmological horizons. The universe could be infinite in extent or it could be finite; but the evidence that leads to the inflationary model of the early universe also implies that the "total universe" is much larger than the observable universe, and so any edges or exotic geometries or topologies would not be directly observable as light has not reached scales on which such aspects of the universe, if they exist, are still allowed. For all intents and purposes, it is safe to assume that the universe is infinite in spatial extent, without edge or strange connectedness.[15]

Regardless of the overall shape of the universe, the question of what the universe is expanding into is one which does not require an answer according to the theories which describe the expansion; the way we define space in our universe in no way requires additional exterior space into which it can expand since an expansion of an infinite expanse can happen without changing the infinite extent of the expanse. All that is certain is that the manifold of space in which we live simply has the property that the distances between objects are getting larger as time goes on. This only implies the simple observational consequences associated with the metric expansion explored below. No "outside" or embedding in hyperspace is required for an expansion to occur. The visualizations often seen of the universe growing as a bubble into nothingness are misleading in that respect. There is no reason to believe there is anything "outside" of the expanding universe into which the universe expands.

Even if the overall spatial extent is infinite and thus the universe cannot get any "larger", we still say that space is expanding because, locally, the characteristic distance between objects is increasing. As an infinite space grows, it remains infinite.

Density of universe during expansion

Despite being extremely dense when very young and during part of its early expansion - far denser than is usually required to form a black hole - the universe did not re-collapse into a black hole. This is because commonly-used calculations for gravitational collapse are usually based upon objects of relatively constant size, such as stars, and do not apply to rapidly expanding space such as the Big Bang.Effects of expansion on small scales

The expansion of space is sometimes described as a force which acts to push objects apart. Though this is an accurate description of the effect of the cosmological constant, it is not an accurate picture of the phenomenon of expansion in general. For much of the universe's history the expansion has been due mainly to inertia. The matter in the very early universe was flying apart for unknown reasons (most likely as a result of cosmic inflation) and has simply continued to do so, though at an ever-decreasing[citation needed] rate due to the attractive effect of gravity.

Animation of an expanding raisin bread model. As the bread doubles in

width (depth and length), the distances between raisins also double.

In addition to slowing the overall expansion, gravity causes local clumping of matter into stars and galaxies. Once objects are formed and bound by gravity, they "drop out" of the expansion and do not subsequently expand under the influence of the cosmological metric, there being no force compelling them to do so.

There is no difference between the inertial expansion of the universe and the inertial separation of nearby objects in a vacuum; the former is simply a large-scale extrapolation of the latter.

Once objects are bound by gravity, they no longer recede from each other. Thus, the Andromeda galaxy, which is bound to the Milky Way galaxy, is actually falling towards us and is not expanding away. Within the Local Group, the gravitational interactions have changed the inertial patterns of objects such that there is no cosmological expansion taking place. Once one goes beyond the Local Group, the inertial expansion is measurable, though systematic gravitational effects imply that larger and larger parts of space will eventually fall out of the "Hubble Flow" and end up as bound, non-expanding objects up to the scales of superclusters of galaxies. We can predict such future events by knowing the precise way the Hubble Flow is changing as well as the masses of the objects to which we are being gravitationally pulled. Currently, the Local Group is being gravitationally pulled towards either the Shapley Supercluster or the "Great Attractor" with which, if dark energy were not acting, we would eventually merge and no longer see expand away from us after such a time.

A consequence of metric expansion being due to inertial motion is that a uniform local "explosion" of matter into a vacuum can be locally described by the FLRW geometry, the same geometry which describes the expansion of the universe as a whole and was also the basis for the simpler Milne universe which ignores the effects of gravity. In particular, general relativity predicts that light will move at the speed c with respect to the local motion of the exploding matter, a phenomenon analogous to frame dragging.

The situation changes somewhat with the introduction of dark energy or a cosmological constant. A cosmological constant due to a vacuum energy density has the effect of adding a repulsive force between objects which is proportional (not inversely proportional) to distance. Unlike inertia it actively "pulls" on objects which have clumped together under the influence of gravity, and even on individual atoms. However, this does not cause the objects to grow steadily or to disintegrate; unless they are very weakly bound, they will simply settle into an equilibrium state which is slightly (undetectably) larger than it would otherwise have been. As the universe expands and the matter in it thins, the gravitational attraction decreases (since it is proportional to the density), while the cosmological repulsion increases; thus the ultimate fate of the ΛCDM universe is a near vacuum expanding at an ever-increasing rate under the influence of the cosmological constant. However, the only locally visible effect of the accelerating expansion is the disappearance (by runaway redshift) of distant galaxies; gravitationally bound objects like the Milky Way do not expand and the Andromeda galaxy is moving fast enough towards us that it will still merge with the Milky Way in 3 billion years time, and it is also likely that the merged supergalaxy that forms will eventually fall in and merge with the nearby Virgo Cluster. However, galaxies lying farther away from this will recede away at ever-increasing speed and be redshifted out of our range of visibility.

Metric expansion and speed of light

At the end of the early universe's inflationary period, all the matter and energy in the universe was set on an inertial trajectory consistent with the equivalence principle and Einstein's general theory of relativity and this is when the precise and regular form of the universe's expansion had its origin (that is, matter in the universe is separating because it was separating in the past due to the inflaton field)[citation needed].While special relativity prohibits objects from moving faster than light with respect to a local reference frame where spacetime can be treated as flat and unchanging, it does not apply to situations where spacetime curvature or evolution in time become important. These situations are described by general relativity, which allows the separation between two distant objects to increase faster than the speed of light, although the definition of "distance" here is somewhat different from that used in an inertial frame. The definition of distance used here is the summation or integration of local comoving distances, all done at constant local proper time. For example, galaxies that are more than the Hubble radius, approximately 4.5 gigaparsecs or 14.7 billion light-years, away from us have a recession speed that is faster than the speed of light. Visibility of these objects depends on the exact expansion history of the universe. Light that is emitted today from galaxies beyond the cosmological event horizon, about 5 gigaparsecs or 16 billion light-years, will never reach us, although we can still see the light that these galaxies emitted in the past.

Because of the high rate of expansion, it is also possible for a distance between two objects to be greater than the value calculated by multiplying the speed of light by the age of the universe. These details are a frequent source of confusion among amateurs and even professional physicists.[3] Due to the non-intuitive nature of the subject and what has been described by some as "careless" choices of wording, certain descriptions of the metric expansion of space and the misconceptions to which such descriptions can lead are an ongoing subject of discussion in the realm of pedagogy and communication of scientific concepts.[4][5][6][7] In June 2016, NASA and ESA scientists reported that the universe was found to be expanding 5% to 9% faster than thought earlier, based on studies using the Hubble Space Telescope.[2]

Scale factor

At a fundamental level, the expansion of the universe is a property of spatial measurement on the largest measurable scales of our universe. The distances between cosmologically relevant points increases as time passes leading to observable effects outlined below. This feature of the universe can be characterized by a single parameter that is called the scale factor which is a function of time and a single value for all of space at any instant (if the scale factor were a function of space, this would violate the cosmological principle). By convention, the scale factor is set to be unity at the present time and, because the universe is expanding, is smaller in the past and larger in the future. Extrapolating back in time with certain cosmological models will yield a moment when the scale factor was zero; our current understanding of cosmology sets this time at 13.799 ± 0.021 billion years ago. If the universe continues to expand forever, the scale factor will approach infinity in the future. In principle, there is no reason that the expansion of the universe must be monotonic and there are models where at some time in the future the scale factor decreases with an attendant contraction of space rather than an expansion.Other conceptual models of expansion

The expansion of space is often illustrated with conceptual models which show only the size of space at a particular time, leaving the dimension of time implicit.In the "ant on a rubber rope model" one imagines an ant (idealized as pointlike) crawling at a constant speed on a perfectly elastic rope which is constantly stretching. If we stretch the rope in accordance with the ΛCDM scale factor and think of the ant's speed as the speed of light, then this analogy is numerically accurate — the ant's position over time will match the path of the red line on the embedding diagram above.

In the "rubber sheet model" one replaces the rope with a flat two-dimensional rubber sheet which expands uniformly in all directions. The addition of a second spatial dimension raises the possibility of showing local perturbations of the spatial geometry by local curvature in the sheet.

In the "balloon model" the flat sheet is replaced by a spherical balloon which is inflated from an initial size of zero (representing the big bang). A balloon has positive Gaussian curvature while observations suggest that the real universe is spatially flat, but this inconsistency can be eliminated by making the balloon very large so that it is locally flat to within the limits of observation. This analogy is potentially confusing since it wrongly suggests that the big bang took place at the center of the balloon. In fact points off the surface of the balloon have no meaning, even if they were occupied by the balloon at an earlier time.

In the "raisin bread model" one imagines a loaf of raisin bread expanding in the oven. The loaf (space) expands as a whole, but the raisins (gravitationally bound objects) do not expand; they merely grow farther away from each other.

Theoretical basis and first evidence

The expansion of the universe proceeds in all directions as determined by the Hubble constant.

However, the Hubble constant can change in the past and in the future,

dependent on the observed value of density parameters (Ω). Before the

discovery of dark energy,

it was believed that the universe was matter-dominated, and so Ω on

this graph corresponds to the ratio of the matter density to the critical density ( ).

).

).

).Hubble's law

Technically, the metric expansion of space is a feature of many solutions[which?] to the Einstein field equations of general relativity, and distance is measured using the Lorentz interval. This explains observations which indicate that galaxies that are more distant from us are receding faster than galaxies that are closer to us (see Hubble's law).Cosmological constant and the Friedmann equations

The first general relativistic models predicted that a universe which was dynamical and contained ordinary gravitational matter would contract rather than expand. Einstein's first proposal for a solution to this problem involved adding a cosmological constant into his theories to balance out the contraction, in order to obtain a static universe solution. But in 1922 Alexander Friedmann derived a set of equations known as the Friedmann equations, showing that the universe might expand and presenting the expansion speed in this case.[16] The observations of Edwin Hubble in 1929 suggested that distant galaxies were all apparently moving away from us, so that many scientists came to accept that the universe was expanding.Hubble's concerns over the rate of expansion

While the metric expansion of space appeared to be implied by Hubble's 1929 observations, Hubble disagreed with the expanding-universe interpretation of the data:[…] if redshift are not primarily due to velocity shift […] the velocity-distance relation is linear, the distribution of the nebula is uniform, there is no evidence of expansion, no trace of curvature, no restriction of the time scale […] and we find ourselves in the presence of one of the principles of nature that is still unknown to us today […] whereas, if redshifts are velocity shifts which measure the rate of expansion, the expanding models are definitely inconsistent with the observations that have been made […] expanding models are a forced interpretation of the observational results.

[If the redshifts are a Doppler shift …] the observations as they stand lead to the anomaly of a closed universe, curiously small and dense, and, it may be added, suspiciously young. On the other hand, if redshifts are not Doppler effects, these anomalies disappear and the region observed appears as a small, homogeneous, but insignificant portion of a universe extended indefinitely both in space and time.Hubble's skepticism about the universe being too small, dense, and young turned out to be based on an observational error. Later investigations appeared to show that Hubble had confused distant H II regions for Cepheid variables and the Cepheid variables themselves had been inappropriately lumped together with low-luminosity RR Lyrae stars causing calibration errors that led to a value of the Hubble Constant of approximately 500 km/s/Mpc instead of the true value of approximately 70 km/s/Mpc. The higher value meant that an expanding universe would have an age of 2 billion years (younger than the Age of the Earth) and extrapolating the observed number density of galaxies to a rapidly expanding universe implied a mass density that was too high by a similar factor, enough to force the universe into a peculiar closed geometry which also implied an impending Big Crunch that would occur on a similar time-scale. After fixing these errors in the 1950s, the new lower values for the Hubble Constant accorded with the expectations of an older universe and the density parameter was found to be fairly close to a geometrically flat universe.[19]

— E. Hubble, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 97, 506, 1937 [18]

However, recent measurements of the distances and velocities of faraway galaxies revealed a 9 percent discrepancy in the value of the Hubble constant, implying a universe that seems expanding too fast compared to previous measurements.[20] In 2001, Dr. Wendy Freedman determined space to expand at 72 kilometers per second per megaparsec - roughly 3.3 million light years - meaning that as we move away from Earth every 3.3 million light years is moving 72 kilometers a second faster.[20] In the summer of 2016, another measurement reported a value of 73 for the constant, thereby contradicting 2013 measurements from the European Planck mission of slower expansion value of 67. The discrepancy opened new questions concerning the nature of dark energy, or of neutrinos.[20]

Inflation as an explanation for the expansion

Until the theoretical developments in the 1980s no one had an explanation for why this seemed to be the case, but with the development of models of cosmic inflation, the expansion of the universe became a general feature resulting from vacuum decay. Accordingly, the question "why is the universe expanding?" is now answered by understanding the details of the inflation decay process which occurred in the first 10−32 seconds of the existence of our universe.[21] During inflation, the metric changed exponentially, causing any volume of space that was smaller than an atom to grow to around 100 million light years across in a time scale similar to the time when inflation occurred (10−32 seconds).Measuring distance in a metric space

A diagram depicting the expansion of the universe and the appearance of

galaxies moving away from a single galaxy. The phenomenon is relative to

the observer. Object t1 is a smaller expansion than t2.

Each section represents the movement of the red galaxies over the white

galaxies for comparison. The blue and green galaxies are markers to show

which galaxy is the same one (fixed center point) in the subsequent

box. t = time.

In expanding space, distance is a dynamic quantity which changes with time. There are several different ways of defining distance in cosmology, known as distance measures, but a common method used amongst modern astronomers is comoving distance.

The metric only defines the distance between nearby (so-called "local") points. In order to define the distance between arbitrarily distant points, one must specify both the points and a specific curve (known as a "spacetime interval") connecting them. The distance between the points can then be found by finding the length of this connecting curve through the three dimensions of space. Comoving distance defines this connecting curve to be a curve of constant cosmological time. Operationally, comoving distances cannot be directly measured by a single Earth-bound observer. To determine the distance of distant objects, astronomers generally measure luminosity of standard candles, or the redshift factor 'z' of distant galaxies, and then convert these measurements into distances based on some particular model of spacetime, such as the Lambda-CDM model. It is, indeed, by making such observations that it was determined that there is no evidence for any 'slowing down' of the expansion in the current epoch.

Observational evidence

Theoretical cosmologists developing models of the universe have drawn upon a small number of reasonable assumptions in their work. These workings have led to models in which the metric expansion of space is a likely feature of the universe. Chief among the underlying principles that result in models including metric expansion as a feature are:- the Cosmological Principle which demands that the universe looks the same way in all directions (isotropic) and has roughly the same smooth mixture of material (homogeneous).

- the Copernican Principle which demands that no place in the universe is preferred (that is, the universe has no "starting point").

- Hubble demonstrated that all galaxies and distant astronomical objects were moving away from us, as predicted by a universal expansion.[23] Using the redshift of their electromagnetic spectra to determine the distance and speed of remote objects in space, he showed that all objects are moving away from us, and that their speed is proportional to their distance, a feature of metric expansion. Further studies have since shown the expansion to be highly isotropic and homogeneous, that is, it does not seem to have a special point as a "center", but appears universal and independent of any fixed central point.

- In studies of large-scale structure of the cosmos taken from redshift surveys a so-called "End of Greatness" was discovered at the largest scales of the universe. Until these scales were surveyed, the universe appeared "lumpy" with clumps of galaxy clusters and superclusters and filaments which were anything but isotropic and homogeneous. This lumpiness disappears into a smooth distribution of galaxies at the largest scales.

- The isotropic distribution across the sky of distant gamma-ray bursts and supernovae is another confirmation of the Cosmological Principle.

- The Copernican Principle was not truly tested on a cosmological scale until measurements of the effects of the cosmic microwave background radiation on the dynamics of distant astrophysical systems were made. A group of astronomers at the European Southern Observatory noticed, by measuring the temperature of a distant intergalactic cloud in thermal equilibrium with the cosmic microwave background, that the radiation from the Big Bang was demonstrably warmer at earlier times.[24] Uniform cooling of the cosmic microwave background over billions of years is strong and direct observational evidence for metric expansion.