| CT scan | |

|---|---|

Modern CT scanner

| |

| Other names | X-ray computed tomography (X-ray CT), computerized axial tomography scan (CAT scan), computer aided tomography, computed tomography scan |

| ICD-10-PCS | B?2 |

| ICD-9-CM | 88.38 |

| MeSH | D014057 |

| OPS-301 code | 3–20...3–26 |

| MedlinePlus | 003330 |

A CT scan, also known as computed tomography scan, and formerly known as a computerized axial tomography scan or CAT scan, makes use of computer-processed combinations of many X-ray measurements taken from different angles to produce cross-sectional (tomographic) images (virtual "slices") of specific areas of a scanned object, allowing the user to see inside the object without cutting.

Digital geometry processing is used to further generate a three-dimensional volume of the inside of the object from a large series of two-dimensional radiographic images taken around a single axis of rotation. Medical imaging is the most common application of X-ray CT. Its cross-sectional images are used for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes in various medical disciplines. The rest of this article discusses medical-imaging X-ray CT; industrial applications of X-ray CT are discussed at industrial computed tomography scanning.

The term "computed tomography" (CT) is often used to refer to X-ray CT, because it is the most commonly known form. But, many other types of CT exist, such as positron emission tomography (PET) and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT). X-ray tomography, a predecessor of CT, is one form of radiography, along with many other forms of tomographic and non-tomographic radiography.

CT produces data that can be manipulated in order to demonstrate various bodily structures based on their ability to absorb the X-ray beam. Although, historically, the images generated were in the axial or transverse plane, perpendicular to the long axis of the body, modern scanners allow this volume of data to be reformatted in various planes or even as volumetric (3D) representations of structures. Although most common in medicine, CT is also used in other fields, such as nondestructive materials testing. Another example is archaeological uses such as imaging the contents of sarcophagi or ceramics. Individuals responsible for performing CT exams are called radiographers or radiologic technologists.

Use of CT has increased dramatically over the last two decades in many countries. An estimated 72 million scans were performed in the United States in 2007 and more than 80 million a year in 2015. One study estimated that as many as 0.4% of current cancers in the United States are due to CTs performed in the past and that this may increase to as high as 1.5 to 2% with 2007 rates of CT use; however, this estimate is disputed, as there is not a consensus about the existence of damage from low levels of radiation. Lower radiation doses are often used in many areas, such as in the investigation of renal colic. Side effects from intravenous contrast used in some types of studies include the possibility of exacerbating kidney problems in the setting of pre-existing kidney disease.

Medical use

Since its introduction in the 1970s, CT has become an important tool in medical imaging to supplement X-rays and medical ultrasonography. It has more recently been used for preventive medicine or screening

for disease, for example CT colonography for people with a high risk of

colon cancer, or full-motion heart scans for people with high risk of

heart disease. A number of institutions offer full-body scans

for the general population although this practice goes against the

advice and official position of many professional organizations in the

field primarily due to the radiation dose applied.

Head

Computed tomography of human brain, from base of the skull to top. Taken with intravenous contrast medium.

CT scanning of the head is typically used to detect infarction, tumors, calcifications, haemorrhage and bone trauma. Of the above, hypodense (dark) structures can indicate edema

and infarction, hyperdense (bright) structures indicate calcifications

and haemorrhage and bone trauma can be seen as disjunction in bone

windows. Tumors can be detected by the swelling and anatomical

distortion they cause, or by surrounding edema. Ambulances equipped with

small bore multi-sliced CT scanners respond to cases involving stroke

or head trauma. CT scanning of the head is also used in CT-guided stereotactic surgery and radiosurgery

for treatment of intracranial tumors, arteriovenous malformations and

other surgically treatable conditions using a device known as the N-localizer.

Magnetic resonance imaging

(MRI) of the head provides superior information as compared to CT scans

when seeking information about headache to confirm a diagnosis of neoplasm, vascular disease, posterior cranial fossa lesions, cervicomedullary lesions, or intracranial pressure disorders. It also does not carry the risks of exposing the patient to ionizing radiation. CT scans may be used to diagnose headache when neuroimaging is indicated and MRI is not available, or in emergency settings when hemorrhage, stroke, or traumatic brain injury are suspected.

Even in emergency situations, when a head injury is minor as determined

by a physician's evaluation and based on established guidelines, CT of

the head should be avoided for adults and delayed pending clinical

observation in the emergency department for children.

Lungs

High-resolution computed tomographs of a normal thorax, taken in the axial, coronal and sagittal planes, respectively.

Bronchial wall thickness (T) and diameter (D).

Bronchial wall thickening can be seen on lung CTs, and generally (but not always) implies inflammation of the bronchi. Normally, the ratio of the bronchial wall thickness and the bronchial diameter is between 0.17 and 0.23.

An incidentally found nodule in the absence of symptoms (sometimes referred to as an incidentaloma) may raise concerns that it might represent a tumor, either benign or malignant.

Perhaps persuaded by fear, patients and doctors sometimes agree to an

intensive schedule of CT scans, sometimes up to every three months and

beyond the recommended guidelines, in an attempt to do surveillance on

the nodules.

However, established guidelines advise that patients without a prior

history of cancer and whose solid nodules have not grown over a two-year

period are unlikely to have any malignant cancer.

For this reason, and because no research provides supporting evidence

that intensive surveillance gives better outcomes, and because of risks

associated with having CT scans, patients should not receive CT

screening in excess of those recommended by established guidelines.

Angiography

Example of a CTPA, demonstrating a saddle embolus (dark horizontal line) occluding the pulmonary arteries (bright white triangle)

Computed tomography angiography (CTA) is contrast CT to visualize arterial and venous vessels throughout the body. This ranges from arteries serving the brain to those bringing blood to the lungs, kidneys, arms and legs. An example of this type of exam is CT pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) used to diagnose pulmonary embolism (PE). It employs computed tomography and an iodine based contrast agent to obtain an image of the pulmonary arteries.

Cardiac

A CT scan of the heart is performed to gain knowledge about cardiac or coronary anatomy. Traditionally, cardiac CT scans are used to detect, diagnose or follow up coronary artery disease.

More recently CT has played a key role in the fast evolving field of

transcatheter structural heart interventions, more specifically in the

transcatheter repair and replacement of heart valves.

The main forms of cardiac CT scanning are:

- Coronary CT angiography (CTA): the use of CT to assess the coronary arteries of the heart. The subject receives an intravenous injection of radiocontrast and then the heart is scanned using a high speed CT scanner, allowing radiologists to assess the extent of occlusion in the coronary arteries, usually in order to diagnose coronary artery disease.

- Coronary CT calcium scan: also used for the assessment of severity of coronary artery disease. Specifically, it looks for calcium deposits in the coronary arteries that can narrow arteries and increase the risk of heart attack. A typical coronary CT calcium scan is done without the use of radiocontrast, but it can possibly be done from contrast-enhanced images as well.

To better visualize the anatomy, post-processing of the images is common.

Most common are multiplanar reconstructions (MPR) and volume rendering.

For more complex anatomies and procedures, such as heart valve

interventions, a true 3D reconstruction or a 3D print is created based on these CT images to gain a deeper understanding.

Abdominal and pelvic

CT scan of a normal abdomen and pelvis, taken in the axial, coronal and sagittal planes, respectively.

CT is an accurate technique for diagnosis of abdominal

diseases. Its uses include diagnosis and staging of cancer, as well as

follow up after cancer treatment to assess response. It is commonly used

to investigate acute abdominal pain.

Axial skeleton and extremities

Normal cervical vertebrae

For the axial skeleton and extremities, CT is often used to image complex fractures,

especially ones around joints, because of its ability to reconstruct

the area of interest in multiple planes. Fractures, ligamentous injuries

and dislocations can easily be recognised with a 0.2 mm resolution. With modern Dual-energy CT scanners, new areas of use have been established, such as aiding in the diagnosis of gout.

Advantages

There are several advantages that CT has over traditional 2D medical radiography.

First, CT completely eliminates the superimposition of images of

structures outside the area of interest. Second, because of the inherent

high-contrast resolution of CT, differences between tissues that differ

in physical density by less than 1% can be distinguished. Finally, data

from a single CT imaging procedure consisting of either multiple

contiguous or one helical scan can be viewed as images in the axial, coronal, or sagittal planes, depending on the diagnostic task. This is referred to as multiplanar reformatted imaging.

CT is regarded as a moderate- to high-radiation

diagnostic technique. The improved resolution of CT has permitted the

development of new investigations, which may have advantages; compared

to conventional radiography, for example, CT angiography avoids the

invasive insertion of a catheter. CT colonography (also known as virtual colonoscopy or VC for short) is far more accurate than a barium enema for detection of tumors, and uses a lower radiation dose. CT VC is increasingly being used in the UK and US as a screening test for colon polyps and colon cancer and can negate the need for a colonoscopy in some cases.

The radiation dose for a particular study depends on multiple

factors: volume scanned, patient build, number and type of scan

sequences, and desired resolution and image quality.

In addition, two helical CT scanning parameters that can be adjusted

easily and that have a profound effect on radiation dose are tube

current and pitch. Computed tomography (CT) scan has been shown to be

more accurate than radiographs in evaluating anterior interbody fusion

but may still over-read the extent of fusion.

Adverse effects

Cancer

The radiation used in CT scans can damage body cells, including DNA molecules, which can lead to radiation-induced cancer.

The radiation doses received from CT scans is variable. Compared to

the lowest dose x-ray techniques, CT scans can have 100 to 1,000 times

higher dose than conventional X-rays. However, a lumbar spine x-ray has a similar dose as a head CT.

Articles in the media often exaggerate the relative dose of CT by

comparing the lowest-dose x-ray techniques (chest x-ray) with the

highest-dose CT techniques. In general, the radiation dose associated

with a routine abdominal CT has a radiation dose similar to 3 years

average background radiation (from cosmic radiation).

Some experts note that CT scans are known to be "overused," and

"there is distressingly little evidence of better health outcomes

associated with the current high rate of scans."

Early estimates of harm from CT are partly based on similar radiation exposures experienced by those present during the atomic bomb explosions in Japan after the Second World War and those of nuclear industry workers. Some experts project that in the future, between three and five percent of all cancers would result from medical imaging.

An Australian study of 10.9 million people reported that the

increased incidence of cancer after CT scan exposure in this cohort was

mostly due to irradiation. In this group one in every 1800 CT scans was

followed by an excess cancer. If the lifetime risk of developing cancer

is 40% then the absolute risk rises to 40.05% after a CT.

Some studies have shown that publications indicating an increased

risk of cancer from typical doses of body CT scans are plagued with

serious methodological limitations and several highly improbable

results, concluding that no evidence indicates such low doses cause any long-term harm.

A person's age plays a significant role in the subsequent risk of cancer. Estimated lifetime cancer mortality risks from an abdominal CT of a 1-year-old is 0.1% or 1:1000 scans.

The risk for someone who is 40 years old is half that of someone who is

20 years old with substantially less risk in the elderly.

The International Commission on Radiological Protection estimates that the risk to a fetus being exposed to 10 mGy (a unit of radiation exposure, see Gray (unit))

increases the rate of cancer before 20 years of age from 0.03% to 0.04%

(for reference a CT pulmonary angiogram exposes a fetus to 4 mGy).

A 2012 review did not find an association between medical radiation and

cancer risk in children noting however the existence of limitations in

the evidences over which the review is based.

CT scans can be performed with different settings for lower

exposure in children with most manufacturers of CT scans as of 2007

having this function built in. Furthermore, certain conditions can require children to be exposed to multiple CT scans. Studies support informing parents of the risks of pediatric CT scanning.

Contrast reactions

In the United States half of CT scans are contrast CTs using intravenously injected radiocontrast agents.

The most common reactions from these agents are mild, including nausea,

vomiting and an itching rash; however, more severe reactions may occur. Overall reactions occur in 1 to 3% with nonionic contrast and 4 to 12% of people with ionic contrast. Skin rashes may appear within a week to 3% of people.

The old radiocontrast agents caused anaphylaxis in 1% of cases while the newer, lower-osmolar agents cause reactions in 0.01–0.04% of cases. Death occurs in about two to 30 people per 1,000,000 administrations, with newer agents being safer.

There is a higher risk of mortality in those who are female, elderly or

in poor health, usually secondary to either anaphylaxis or acute renal

failure.

The contrast agent may induce contrast-induced nephropathy. This occurs in 2 to 7% of people who receive these agents, with greater risk in those who have preexisting renal insufficiency, preexisting diabetes,

or reduced intravascular volume. People with mild kidney impairment are

usually advised to ensure full hydration for several hours before and

after the injection. For moderate kidney failure, the use of iodinated contrast

should be avoided; this may mean using an alternative technique instead

of CT. Those with severe renal failure requiring dialysis require less

strict precautions, as their kidneys have so little function remaining

that any further damage would not be noticeable and the dialysis will

remove the contrast agent; it is normally recommended, however, to

arrange dialysis as soon as possible following contrast administration

to minimize any adverse effects of the contrast.

In addition to the use of intravenous contrast, orally

administered contrast agents are frequently used when examining the

abdomen. These are frequently the same as the intravenous contrast

agents, merely diluted to approximately 10% of the concentration.

However, oral alternatives to iodinated contrast exist, such as very

dilute (0.5–1% w/v) barium sulfate

suspensions. Dilute barium sulfate has the advantage that it does not

cause allergic-type reactions or kidney failure, but cannot be used in

patients with suspected bowel perforation or suspected bowel injury, as

leakage of barium sulfate from damaged bowel can cause fatal peritonitis.

Process

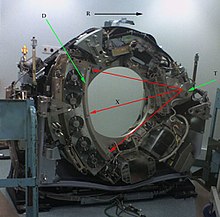

CT scanner with cover removed to show internal components. Legend:

T: X-ray tube

D: X-ray detectors

X: X-ray beam

R: Gantry rotation

T: X-ray tube

D: X-ray detectors

X: X-ray beam

R: Gantry rotation

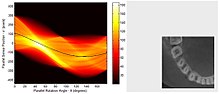

Left image is a sinogram

which is a graphic representation of the raw data obtained from a CT

scan. At right is an image sample derived from the raw data.

Computed tomography operates by using an X-ray generator that rotates around the object; X-ray detectors

are positioned on the opposite side of the circle from the X-ray

source. A visual representation of the raw data obtained is called a

sinogram, yet it is not sufficient for interpretation. Once the scan

data has been acquired, the data must be processed using a form of tomographic reconstruction, which produces a series of cross-sectional images. Pixels in an image obtained by CT scanning are displayed in terms of relative radiodensity. The pixel itself is displayed according to the mean attenuation of the tissue(s) that it corresponds to on a scale from +3071 (most attenuating) to −1024 (least attenuating) on the Hounsfield scale. Pixel

is a two dimensional unit based on the matrix size and the field of

view. When the CT slice thickness is also factored in, the unit is known

as a Voxel,

which is a three-dimensional unit. The phenomenon that one part of the

detector cannot differentiate between different tissues is called the "Partial Volume Effect".

That means that a big amount of cartilage and a thin layer of compact

bone can cause the same attenuation in a voxel as hyperdense cartilage

alone. Water has an attenuation of 0 Hounsfield units

(HU), while air is −1000 HU, cancellous bone is typically +400 HU,

cranial bone can reach 2000 HU or more (os temporale) and can cause artifacts.

The attenuation of metallic implants depends on atomic number of the

element used: Titanium usually has an amount of +1000 HU, iron steel can

completely extinguish the X-ray and is, therefore, responsible for

well-known line-artifacts in computed tomograms. Artifacts are caused by

abrupt transitions between low- and high-density materials, which

results in data values that exceed the dynamic range of the processing

electronics. Two-dimensional CT images are conventionally rendered so

that the view is as though looking up at it from the patient's feet.

Hence, the left side of the image is to the patient's right and vice

versa, while anterior in the image also is the patient's anterior and

vice versa. This left-right interchange corresponds to the view that

physicians generally have in reality when positioned in front of

patients. CT data sets have a very high dynamic range

which must be reduced for display or printing. This is typically done

via a process of "windowing", which maps a range (the "window") of pixel

values to a grayscale ramp. For example, CT images of the brain are

commonly viewed with a window extending from 0 HU to 80 HU. Pixel values

of 0 and lower, are displayed as black; values of 80 and higher are

displayed as white; values within the window are displayed as a grey

intensity proportional to position within the window. The window used

for display must be matched to the X-ray density of the object of

interest, in order to optimize the visible detail.

Contrast

Contrast media used for X-ray CT, as well as for plain film X-ray, are called radiocontrasts. Radiocontrasts for X-ray CT are, in general, iodine-based.

This is useful to highlight structures such as blood vessels that

otherwise would be difficult to delineate from their surroundings. Using

contrast material can also help to obtain functional information about

tissues. Often, images are taken both with and without radiocontrast.

Scan dose

There can be a

wide variation in radiation doses between similar scan types, where the

highest dose could be as much as 22 times higher than the lowest dose.

A typical plain film X-ray involves radiation dose of 0.01 to

0.15 mGy, while a typical CT can involve 10–20 mGy for specific organs,

and can go up to 80 mGy for certain specialized CT scans.

For purposes of comparison, the world average dose rate from naturally occurring sources of background radiation is 2.4 mSv per year, equal for practical purposes in this application to 2.4 mGy per year. While there is some variation, most people (99%) received less than 7 mSv per year as background radiation.

Medical imaging as of 2007 accounted for half of the radiation exposure

of those in the United States with CT scans making up two thirds of

this amount. In the United Kingdom it accounts for 15% of radiation exposure. The average radiation dose from medical sources is ≈0.6 mSv per person globally as of 2007. Those in the nuclear industry in the United States are limited to doses of 50 mSv a year and 100 mSv every 5 years.

Radiation dose units

The radiation dose reported in the gray or mGy

unit is proportional to the amount of energy that the irradiated body

part is expected to absorb, and the physical effect (such as DNA double strand breaks) on the cells' chemical bonds by X-ray radiation is proportional to that energy.

The sievert unit is used in the report of the effective dose.

The sievert unit, in the context of CT scans, does not correspond to

the actual radiation dose that the scanned body part absorbs but to

another radiation dose of another scenario, the whole body absorbing the

other radiation dose and the other radiation dose being of a magnitude,

estimated to have the same probability to induce cancer as the CT scan.

Thus, as is shown in the table above, the actual radiation that is

absorbed by a scanned body part is often much larger than the effective

dose suggests. A specific measure, termed the computed tomography dose index

(CTDI), is commonly used as an estimate of the radiation absorbed dose

for tissue within the scan region, and is automatically computed by

medical CT scanners.

The equivalent dose

is the effective dose of a case, in which the whole body would actually

absorb the same radiation dose, and the sievert unit is used in its

report. In the case of non-uniform radiation, or radiation given to only

part of the body, which is common for CT examinations, using the local

equivalent dose alone would overstate the biological risks to the entire

organism.

Effects of radiation

Most adverse health effects of radiation exposure may be grouped in two general categories:

- deterministic effects (harmful tissue reactions) due in large part to the killing/ malfunction of cells following high doses; and

- stochastic effects, i.e., cancer and heritable effects involving either cancer development in exposed individuals owing to mutation of somatic cells or heritable disease in their offspring owing to mutation of reproductive (germ) cells.

The added lifetime risk of developing cancer by a single abdominal CT of 8 mSv is estimated to be 0.05%, or 1 one in 2,000.

Because of increased susceptibility of fetuses to radiation

exposure, the radiation dosage of a CT scan is an important

consideration in the choice of medical imaging in pregnancy.

Excess doses

In

October, 2009, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) initiated an

investigation of brain perfusion CT (PCT) scans, based on radiation burns

caused by incorrect settings at one particular facility for this

particular type of CT scan. Over 256 patients over an 18-month period

were exposed, over 40% lost patches of hair, and prompted the editorial

to call for increased CT quality assurance programs, while also noting

that "while unnecessary radiation exposure should be avoided, a

medically needed CT scan obtained with appropriate acquisition parameter

has benefits that outweigh the radiation risks." Similar problems have been reported at other centers. These incidents are believed to be due to human error.

Campaigns

In

response to increased concern by the public and the ongoing progress of

best practices, The Alliance for Radiation Safety in Pediatric Imaging

was formed within the Society for Pediatric Radiology. In concert with The American Society of Radiologic Technologists, The American College of Radiology and The American Association of Physicists in Medicine,

the Society for Pediatric Radiology developed and launched the Image

Gently Campaign which is designed to maintain high quality imaging

studies while using the lowest doses and best radiation safety practices

available on pediatric patients.

This initiative has been endorsed and applied by a growing list of

various professional medical organizations around the world and has

received support and assistance from companies that manufacture

equipment used in Radiology.

Following upon the success of the Image Gently campaign,

the American College of Radiology, the Radiological Society of North

America, the American Association of Physicists in Medicine and the

American Society of Radiologic Technologists have launched a similar

campaign to address this issue in the adult population called Image Wisely.

The World Health Organization and International Atomic Energy Agency

(IAEA) of the United Nations have also been working in this area and

have ongoing projects designed to broaden best practices and lower

patient radiation dose.

Prevalence

Patient undergoing a CT scan of the thorax

Use of CT has increased dramatically over the last two decades. An estimated 72 million scans were performed in the United States in 2007. Of these, six to eleven percent are done in children, an increase of seven to eightfold from 1980. Similar increases have been seen in Europe and Asia.

In Calgary, Canada 12.1% of people who present to the emergency with

an urgent complaint received a CT scan, most commonly either of the head

or of the abdomen. The percentage who received CT, however, varied

markedly by the emergency physician who saw them from 1.8% to 25%. In the emergency department in the United States, CT or MRI imaging is done in 15% of people who present with injuries as of 2007 (up from 6% in 1998).

The increased use of CT scans has been the greatest in two

fields: screening of adults (screening CT of the lung in smokers,

virtual colonoscopy, CT cardiac screening, and whole-body CT in

asymptomatic patients) and CT imaging of children. Shortening of the

scanning time to around 1 second, eliminating the strict need for the

subject to remain still or be sedated, is one of the main reasons for

the large increase in the pediatric population (especially for the

diagnosis of appendicitis). As of 2007 in the United States a proportion of CT scans are performed unnecessarily. Some estimates place this number at 30%. There are a number of reasons for this including: legal concerns, financial incentives, and desire by the public. For example, some healthy people avidly pay to receive full-body CT scans as screening, but it is not at all clear that the benefits outweigh the risks and costs, because deciding whether and how to treat incidentalomas is fraught with complexity, radiation exposure is cumulative and not negligible, and the money for the scans involves opportunity cost (it may have been more effectively spent on more targeted screening or other health care strategies).

Presentation

CT creates a volume of voxels.

Types of presentations of CT scans:

- Average intensity projection

- Maximum intensity projection

- Thin slice (median plane)

- Volume rendering by high and low threshold for radiodensity.

- Average intensity projection

- Maximum intensity projection

- Thin slice (median plane)

- Volume rendering by high and low threshold for radiodensity.

The result of a CT scan is a volume of voxels, which may be presented to a human observer by various methods, which broadly fit into the following categories:

- Thin slice. This is generally regarded as planes representing a thickness of less than 3 mm.

- Projection, including maximum intensity projection and average intensity projection

- Volume rendering (VR)

Technically, all volume renderings become projections when viewed on a 2-dimensional display,

making the distinction between projections and volume renderings a bit

vague. Still, the epitomes of volume rendering models feature a mix of

for example coloring and shading in order to create realistic and observable representations.

Two-dimensional CT images are conventionally rendered so that the view is as though looking up at it from the patient's feet.

Hence, the left side of the image is to the patient's right and vice

versa, while anterior in the image also is the patient's anterior and

vice versa. This left-right interchange corresponds to the view that

physicians generally have in reality when positioned in front of

patients.

Grayscale

Pixels in an image obtained by CT scanning are displayed in terms of relative radiodensity. The pixel itself is displayed according to the mean attenuation of the tissue(s) that it corresponds to on a scale from +3071 (most attenuating) to −1024 (least attenuating) on the Hounsfield scale. Pixel

is a two dimensional unit based on the matrix size and the field of

view. When the CT slice thickness is also factored in, the unit is known

as a Voxel, which is a three-dimensional unit. The phenomenon that one part of the detector cannot differentiate between different tissues is called the "Partial Volume Effect".

That means that a big amount of cartilage and a thin layer of compact

bone can cause the same attenuation in a voxel as hyperdense cartilage

alone. Water has an attenuation of 0 Hounsfield units

(HU), while air is −1000 HU, cancellous bone is typically +400 HU,

cranial bone can reach 2000 HU or more (os temporale) and can cause

artifacts. The attenuation of metallic implants depends on atomic number

of the element used: Titanium usually has an amount of +1000 HU, iron

steel can completely extinguish the X-ray and is, therefore, responsible

for well-known line-artifacts in computed tomograms. Artifacts are

caused by abrupt transitions between low- and high-density materials,

which results in data values that exceed the dynamic range of the

processing electronics.

CT data sets have a very high dynamic range

which must be reduced for display or printing. This is typically done

via a process of "windowing", which maps a range (the "window") of pixel

values to a grayscale ramp. For example, CT images of the brain are

commonly viewed with a window extending from 0 HU to 80 HU. Pixel values

of 0 and lower, are displayed as black; values of 80 and higher are

displayed as white; values within the window are displayed as a grey

intensity proportional to position within the window. The window used

for display must be matched to the X-ray density of the object of

interest, in order to optimize the visible detail.

Multiplanar reconstruction and projections

Typical screen layout for diagnostic software, showing one volume rendering (VR) and multiplanar view of three thin slices.

Multiplanar reconstruction (MPR) is the creation of slices in more anatomical planes than the one (usually transverse)

used for initial tomography acquisition. It can be used for thin slices

as well as projections. Multiplanar reconstruction is feasible because

contemporary CT scanners offer isotropic or near isotropic resolution.

MPR is frequently used for examining the spine. Axial images

through the spine will only show one vertebral body at a time and cannot

reliably show the intervertebral discs. By reformatting the volume, it

becomes much easier to visualise the position of one vertebral body in

relation to the others.

Modern software allows reconstruction in non-orthogonal (oblique)

planes so that the optimal plane can be chosen to display an anatomical

structure. This may be particularly useful for visualization of the

structure of the bronchi as these do not lie orthogonal to the direction

of the scan.

For vascular imaging, curved-plane reconstruction can be

performed. This allows bends in a vessel to be "straightened" so that

the entire length can be visualised on one image, or a short series of

images. Once a vessel has been "straightened" in this way, quantitative

measurements of length and cross sectional area can be made, so that

surgery or interventional treatment can be planned.

| Type of projection | Schematic illustration | Examples (10 mm slabs) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average intensity projection (AIP) |

|

The average attenuation of each voxel is displayed. Image will get smoother as slice thickness increases. Will look more and more similar to conventional projectional radiography as slice thickness increases. | |

| Maximum intensity projection (MIP) |

|

The voxel with the highest attenuation is displyed. Therefore, high attenuating structures such as blood vessels filled with contrast media is enhanced. May be used for angiographic studies and identification of pulmonary nodules. | |

| Minimum intensity projection (MinIP) |

|

The voxel with the lowest attenuation is displayed. Therefore, low attenuating structures such air spaces is enhanced. May be used for assessing the lung parenchyma. |

Volume rendering

A threshold value of radiodensity is set by the operator (e.g., a

level that corresponds to bone). From this, a three-dimensional model

can be constructed using edge detection

image processing algorithms and displayed on screen. Multiple models

can be constructed from various thresholds, allowing different colors to

represent each anatomical component such as bone, muscle, and

cartilage. However, the interior structure of each element is not

visible in this mode of operation.

Surface rendering is limited in that it will display only

surfaces that meet a threshold density, and will display only the

surface that is closest to the imaginary viewer. In volume rendering, transparency, colors and shading

are used to allow a better representation of the volume to be shown in a

single image. For example, the bones of the pelvis could be displayed

as semi-transparent, so that, even at an oblique angle, one part of the

image does not conceal another.

Reduced size 3D printed human skull from computed tomography data.

Image quality

A series of CT scans converted into an animated image using Photoshop

Artifacts

Although

images produced by CT are generally faithful representations of the

scanned volume, the technique is susceptible to a number of artifacts, such as the following:

- Streak artifact

- Streaks are often seen around materials that block most X-rays, such as metal or bone. Numerous factors contribute to these streaks: undersampling, photon starvation, motion, beam hardening, and Compton scatter. This type of artifact commonly occurs in the posterior fossa of the brain, or if there are metal implants. The streaks can be reduced using newer reconstruction techniques or approaches such as metal artifact reduction (MAR). MAR techniques include spectral imaging, where CT images are taken with photons of different energy levels, and then synthesized into monochromatic images with special software such as GSI (Gemstone Spectral Imaging).

- Partial volume effect

- This appears as "blurring" of edges. It is due to the scanner being unable to differentiate between a small amount of high-density material (e.g., bone) and a larger amount of lower density (e.g., cartilage). The reconstruction assumes that the X-ray attenuation within each voxel is homogenous; this may not be the case at sharp edges. This is most commonly seen in the z-direction, due to the conventional use of highly anisotropic voxels, which have a much lower out-of-plane resolution, than in-plane resolution. This can be partially overcome by scanning using thinner slices, or an isotropic acquisition on a modern scanner.

- Ring artifact

- Probably the most common mechanical artifact, the image of one or many "rings" appears within an image. They are usually caused by the variations in the response from individual elements in a two dimensional X-ray detector due to defect or miscalibration. Ring artefacts can largely be reduced by intensity normalization, also referred to as flat field correction. Remaining rings can be suppressed by a transformation to polar space, where they become linear stripes. A comparative evaluation of ring artefact reduction on X-ray tomography images showed that the method of Sijbers and Postnov can effectively suppress ring artefacts.

- Noise

- This appears as grain on the image and is caused by a low signal to noise ratio. This occurs more commonly when a thin slice thickness is used. It can also occur when the power supplied to the X-ray tube is insufficient to penetrate the anatomy.

- Windmill

- Streaking appearances can occur when the detectors intersect the reconstruction plane. This can be reduced with filters or a reduction in pitch.

- Beam hardening

- This can give a "cupped appearance" when grayscale is visualized as height. It occurs because conventional sources, like X-ray tubes emit a polychromatic spectrum. Photons of higher photon energy levels are typically attenuated less. Because of this, the mean energy of the spectrum increases when passing the object, often described as getting "harder". This leads to an effect increasingly underestimating material thickness, if not corrected. Many algorithms exist to correct for this artifact. They can be divided in mono- and multi-material methods.

Dose versus image quality

An

important issue within radiology today is how to reduce the radiation

dose during CT examinations without compromising the image quality. In

general, higher radiation doses result in higher-resolution images,

while lower doses lead to increased image noise and unsharp images.

However, increased dosage raises the adverse side effects, including the

risk of radiation-induced cancer – a four-phase abdominal CT gives the same radiation dose as 300 chest X-rays. Several methods that can reduce the exposure to ionizing radiation during a CT scan exist.

- New software technology can significantly reduce the required radiation dose. New iterative tomographic reconstruction algorithms (e.g., iterative Sparse Asymptotic Minimum Variance) could offer superresolution without requiring higher radiation dose.

- Individualize the examination and adjust the radiation dose to the body type and body organ examined. Different body types and organs require different amounts of radiation.

- Prior to every CT examination, evaluate the appropriateness of the exam whether it is motivated or if another type of examination is more suitable. Higher resolution is not always suitable for any given scenario, such as detection of small pulmonary masses.

Industrial use

Industrial CT Scanning

(industrial computed tomography) is a process which utilizes X-ray

equipment to produce 3D representations of components both externally

and internally. Industrial CT scanning has been utilized in many areas

of industry for internal inspection of components. Some of the key uses

for CT scanning have been flaw detection, failure analysis, metrology,

assembly analysis, image-based finite element methods and reverse engineering applications. CT scanning is also employed in the imaging and conservation of museum artifacts.

CT scanning has also found an application in transport security (predominantly airport security where it is currently used in a materials analysis context for explosives detection CTX (explosive-detection device) and is also under consideration for automated baggage/parcel security scanning using computer vision

based object recognition algorithms that target the detection of

specific threat items based on 3D appearance (e.g. guns, knives, liquid

containers).

History

The history of X-ray computed tomography goes back to at least 1917 with the mathematical theory of the Radon transform.

In October 1963, Oldendorf received a U.S. patent for a "radiant energy

apparatus for investigating selected areas of interior objects obscured

by dense material". The first commercially viable CT scanner was invented by Sir Godfrey Hounsfield in 1972.

Etymology

The word "tomography" is derived from the Greek tome (slice) and graphein

(to write). Computed tomography was originally known as the "EMI scan"

as it was developed in the early 1970s at a research branch of EMI, a company best known today for its music and recording business. It was later known as computed axial tomography (CAT or CT scan) and body section röntgenography.

Although the term "computed tomography" could be used to describe positron emission tomography or single photon emission computed tomography

(SPECT), in practice it usually refers to the computation of tomography

from X-ray images, especially in older medical literature and smaller

medical facilities.

In MeSH, "computed axial tomography" was used from 1977 to 1979, but the current indexing explicitly includes "X-ray" in the title.

The term sinogram was introduced by Paul Edholm and Bertil Jacobson in 1975.

Types of machines

Spinning tube, commonly called spiral CT, or helical CT is an imaging technique in which an entire X-ray tube

is spun around the central axis of the area being scanned. These are

the dominant type of scanners on the market because they have been

manufactured longer and offer lower cost of production and purchase. The

main limitation of this type is the bulk and inertia of the equipment

(X-ray tube assembly and detector array on the opposite side of the

circle) which limits the speed at which the equipment can spin. Some

designs use two X-ray sources and detector arrays offset by an angle, as

a technique to improve temporal resolution.

Electron beam tomography

(EBT) is a specific form of CT in which a large enough X-ray tube is

constructed so that only the path of the electrons, travelling between

the cathode and anode of the X-ray tube, are spun using deflection

coils. This type had a major advantage since sweep speeds can be much

faster, allowing for less blurry imaging of moving structures, such as

the heart and arteries. Fewer scanners of this design have been produced

when compared with spinning tube types, mainly due to the higher cost

associated with building a much larger X-ray tube and detector array and

limited anatomical coverage. Only one manufacturer (Imatron, later

acquired by General Electric) ever produced scanners of this design. Production ceased in early 2006.

In multislice computed tomography (MSCT) or multidetector computed tomography (MDCT),

a higher number of tomographic slices allow for higher-resolution

imaging. Modern CT machines typically generate 64-640 slices per scan.

Research directions

Photon counting computed tomography

is a CT technique currently under development. Typical CT scanners use

energy integrating detectors; photons are measured as a voltage on a

capacitor which is proportional to the x-rays detected. However, this

technique is susceptible to noise and other factors which can affect the

linearity of the voltage to x-ray intensity relationship.

Photon counting detectors (PCDs) are still affected by noise but it

does not change the measured counts of photons. PCDs have several

potential advantages including improving signal (and contrast) to noise

ratios, reducing doses, improving spatial resolution and, through use of

several energies, distinguishing multiple contrast agents.

PCDs have only recently become feasible in CT scanners due to

improvements in detector technologies that can cope with the volume and

rate of data required. As of February 2016 photon counting CT is in use

at three sites. Some early research has found the dose reduction potential of photon counting CT for breast imaging to be very promising.