| Summerhill School | |

|---|---|

| |

| Address | |

Westward Ho

, ,

IP16 4HY

England

| |

| Coordinates | 52.211222°N 1.572639°ECoordinates: 52.211222°N 1.572639°E |

| Information | |

| Type | Independent Boarding School |

| Established | 1921 |

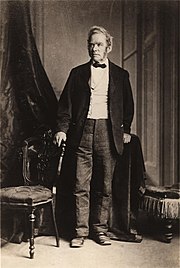

| Founder | Alexander Sutherland Neill |

| Local authority | Suffolk |

| Department for Education URN | 124870 Tables |

| Ofsted | Reports |

| Principal | Zoë Readhead |

| Staff | Approx. 10 teaching, 5 support |

| Gender | Coeducational |

| Age | 6 to 18 |

| Enrolment | 78 pupils |

| Houses | San, Cottage, House, Shack, Carriage |

| Publication | The Orange Peel Magazine |

| Website | http://www.summerhillschool.co.uk |

Summerhill School is an independent (i.e. fee-paying) British boarding school that was founded in 1921 by Alexander Sutherland Neill with the belief that the school should be made to fit the child, rather than the other way around. It is run as a democratic community; the running of the school is conducted in the school meetings, which anyone, staff or pupil, may attend, and at which everyone has an equal vote. These meetings serve as both a legislative and judicial body. Members of the community are free to do as they please, so long as their actions do not cause any harm to others, according to Neill's principle "Freedom, not Licence." This extends to the freedom for pupils to choose which lessons, if any, they attend. It is an example of both democratic education and alternative education.

History

In

1920, A. S. Neill started to search for premises in which to found a

new school which he could run according to his educational principle of

giving freedom to the children and staff through democratic governance.

On a trip to Europe, which started out as a research visit into progressive schools on behalf of the Theosophical journal New Era, he found the ideal accommodation in Hellerau near Dresden, a village founded on principles that presaged the Garden City movement in England. By combining with two other Projects, the Neue Deutsche Schule

(New German School), founded by Carl Thiess the previous year and an

existing school with many international students dedicated to the

teaching of Eurhythmics, a joint venture named the International School or Neue Schule Hellerau

was launched. Neill's sector was called the "foreign" school (in

contrast to the Thiess's "German School"). Jonathan Croall wrote, "This,

in essence, was the beginning of Summerhill" although the name Summerhill itself came later.

Neill was soon dissatisfied with Neue Schule's ethos, and moved his sector of the organisation to Sonntagberg in Austria. Due to the hostility of the local people, it moved again in 1923 to Lyme Regis

in England. The house in Lyme Regis was called Summerhill, and this

became the name of the school. In 1927, it moved to its present site in Leiston, Suffolk, England. It had to move again temporarily to Ffestiniog, Wales, during the Second World War so that the site could be used as a British Army training camp.

After Neill died in 1973, it was run by his wife, Ena May Neill, until 1985.

Today it is a boarding and day school serving primary and secondary education in a democratic fashion. It is now run by Neill's daughter, Zoë Readhead.

Although the school's founding could arguably be dated to other

years, the school itself marks 1921 as the year of its establishment.

Schools based on Summerhill

Many schools opened based on Summerhill, especially in America in the 1960s. A common challenge was to implement Neill's dictum of "Freedom, not licence":

"A free school is not a place where you can run roughshod over other

people. It's a place that minimises the authoritarian elements and

maximises the development of community and really caring about the other

people. Doing this is a tricky business."

Neill distanced himself from some schools for confusing freedom

and licence: "Look at those American Summerhill schools. I sent a letter

to the Greenwich Village Voice,

in New York, disclaiming any affiliation with any American school that

calls itself a Summerhill school. I've heard so many rumours about them.

It's one thing to use freedom. Quite another to use licence."

Government inspections

Summerhill

has had a less-than-perfect relationship with the British government.

Already in the 1950s a government inspection found the school's finances

were shaky, the number of students too high, and the quality of

teaching poor among the junior faculty. In spite of these criticisms

however, the inspectors apparently found the school praiseworthy.

During the 1990s, the school was inspected nine times. It later emerged that this was because OFSTED (The "OFfice for STandards in EDucation") had placed Summerhill on a secret list of 61 independent schools marked as TBW (To Be Watched).

In March 1999, following a major inspection from OFSTED, the then Secretary of State for Education and Employment, David Blunkett,

issued the school a notice of complaint, based on the school's policy

of non-compulsory lessons. Failure to comply with such a notice within

six months usually leads to closure; however, Summerhill chose to

contest the notice in court.

The case went before a special educational tribunal in March

2000, at which the school was represented by noted human rights lawyers Geoffrey Robertson QC and Mark Stephens.

Four days into the hearing, the government's case collapsed and a

settlement was agreed. The pupils attending the hearing on that day took

over the courtroom and held a school meeting to debate whether to

accept the settlement. They voted unanimously to do so.

The nature of the settlement was notably broader than could have

been decided on the judge's authority alone. The educational tribunal

only had the power to annul the notice of complaint, whereas the

settlement made provisions that Summerhill be inspected with respect to

its philosophy and values, that the voice of the child (through

community meetings and in other ways) be included in the inspection, and

that the inspectors be accompanied by two advisers from the school and

one from the DfE to ensure that the inspection respected the school's

aims and values. The school was the first in England to grant children a

legal right to formally express their opinions and to meet with the

inspectors. The DfE advisers have included Prof. Paul Hirst and Prof.

Geoff Whitty, Director of the Institute of Education and now on OFSTED's

governing body.

The first full inspection report since the disputed 1999 report was published in 2007.

The 2007 inspection, conducted within the framework set out by the

court settlement, was generally positive, even in areas previously

criticised by the 1999 report. The school maintained that it had not

changed its approach since the original inspection.

The full inspection on 5 October 2011 concluded that the school

is outstanding in all areas except teaching, which was seen as good, and

not outstanding due to issues of assessment.

In February 2013, the DfE unilaterally rescinded the court

agreement by claiming that OFSTED now understood the school and the

court mandated inspection process was no longer needed to ensure a fair

inspection. The school sent evidence and questions to the Select

Committee on Education for their meeting with the Chief Inspector of

Schools, Sir Michael Wilshaw, on 13 February 2013. The evidence quoted a

member of the Select Committee expressing shock at the lack of

processes for OFSTED to learn by its mistakes.

A. S. Neill Summerhill Trust

The

A. S. Neill Summerhill Trust was launched in 2004 by Prof. Tim

Brighouse, Tom Conti, Bill Nighy, Mark Stephens and Geoffrey Robertson

QC to raise funds for bursaries

for pupils from poorer families and to promote democratic education

around the world. It publishes an electronic newsletter and organises

fund-raising events. An elected committee of schoolchildren, called the

"External Affairs Committee", have—over the years since the court case

and with the support of the Trust—promoted Summerhill as a case study to

state schoolchildren, teachers and educationalists at conferences,

schools and events. They have run full democratic meetings at the Houses of Parliament and London's City Hall.

They have lobbied four chief inspectors of schools through the Select

Committee on Education on the importance of children's rights in schools

and school inspections. They have addressed the UNESCO Conference of

Education Ministers, lobbied and protested at the UN Special Conference on the Rights of the Child in New York. They took an active part in advising and contributing to events for the children's rights group Article 12. They continue to work with schools, colleges and universities.

Philosophy and educational structure

Summerhill is noted for its philosophy that children learn best with

freedom from coercion. A philosophy that was promoted by the New Ideals

in Education Conferences (1914–37) that helped to define the good modern primary school as child-centred.

All lessons are optional, and pupils are free to choose what to do with

their time. Neill founded Summerhill with the belief that "the function

of a child is to live his own life—–not the life that his anxious

parents think he should live, not a life according to the purpose of an

educator who thinks he knows best."

In addition to taking control of their own time, pupils can

participate in the self-governing community of the school. School

meetings are held twice a week, where pupils and staff alike have an

equal voice in the decisions that affect their day-to-day lives,

discussing issues and creating or changing school laws. The rules agreed

at these meetings are wide ranging—from agreeing on acceptable bed

times to making nudity allowed around the pool

and within the classrooms. Meetings are also an opportunity for the

community to vote on a course of action for unresolved conflicts, such

as a fine for a theft (usually the fine consists of having to pay back

the amount stolen). If there is an urgent reason to have a meeting,

children and staff can ask the chairperson to hold a special meeting,

and this is written on the main whiteboard, before a meal time, so that the whole school knows and can attend.

In creating its laws and dealing out sanctions, the school

meeting generally applies A. S. Neill's maxim "Freedom not Licence" (he

wrote a book of the same name); the principle that you can do as you

please, so long as it doesn't cause harm to others. For example, pupils

may swear within the school grounds, but calling someone else an offensive name is licence.

Classes are voluntary at Summerhill.

Although most students attend, depending on their age and reasons,

children choose whether to go of their own accord and without adult

compulsion.

The staff discuss new children and those who they feel may have issues

that interfere with their freedom to choose (e.g., fear of classrooms,

shyness to learn in front of others, lack of confidence), and propose

and vote on interventions, if needed, during staff meetings. This is

called the 'Special Attention List'.

The staff meet at least twice a week to discuss issues; those relevant

to the community will be brought to a community meeting. Children can

attend these meetings when they ask, but are asked to leave when

individual students are discussed, to maintain the privacy of the

student.

Academics

Although

Neill was more concerned with the social development of children than

their academic development, Summerhill nevertheless has some important

differences in its approach to teaching. There is no concept of a "year"

or "form" at Summerhill. Instead, children are placed according to

their interest or level of understanding in a given subject. It is not

uncommon for a single class to have pupils of widely varying ages, or

for pupils as young as 13 or 14 to take GCSE

examinations. This structure reflects a belief that children should

progress at their own pace, rather than having to meet a set standard by

a certain age.

There are also two classrooms which operate on a "drop-in" basis

for all or part of the day, the workshop and the art room. Anyone can

come to these classrooms and, with supervision, make just about

anything. Children commonly play with wooden toys (usually swords or guns) they have made themselves, and much of the furniture and décor in the school has been likewise constructed by students.

Neill believed that children who were educated in this way were

better prepared than traditionally educated children for most of life's

challenges—including higher education. He wrote that Summerhill students

who decided to prepare for university entrance exams were able to

finish the material faster than pupils of traditional schools.

Inspector accounts assert that this was inaccurate, and that interested

pupils were disadvantaged by their dearth of preparation.

However, Michael Newman has argued that the inspectors assumed that

lesson attendance was necessary evidence of children learning, and that

lack of attendance was equated with a lack of learning. Newman says the

inspectors refused to accept as evidence the students' exam results,

verbal evidence from teachers, current and previous children, and the

success of children after leaving Summerhill.

The Summerhill classroom was popularly assumed to reflect Neill's

anti-authoritarian beliefs, but in fact classes were traditional in

practice. Neill did not show outward interest in classroom pedagogy, and was mainly interested in pupil happiness. He did not consider lesson quality important, and thus there were no distinctive Summerhillian classroom methods. Neill also felt that charismatic teachers taught with persuasion that weakened child autonomy.

Today the school peer-reviews its teachers, and has policies and systems in place to ensure the quality of teaching.

Since Zoë Readhead took over as Principal, the school has developed an

ethos of keeping its staff, through increase in wages and conditions of

work. And there is an ongoing review and development of methods of

teaching, assessment and record-keeping.

The staff now share with each other their methods, especially in

relation to numeracy and literacy learning. The music department have

developed over several years, including action research, methods of

supporting spontaneous music performance, creativity and development of

expression through music. This is being shared with the rest of the

staff. The school has always had a creative drama delivery, based on

spontaneous acting and development of plays through collaboration

between actors, directors and writers. With small-group teaching and

negotiated timetables, the curriculum is presented in multi-sensory,

individual-focused lessons, with flexibility to respond to the student's

needs.

Boarding houses and pastoral care

Children

at Summerhill are placed in one of five groups which correspond to the

buildings in which they are accommodated. Placement is generally decided

at the beginning of term by the Principal, in theory according to age.

In practice, a younger child may take priority if they have been waiting

a long time for a place, if they have many friends in the upper group,

or if they show a maturity characteristic of a member of the upper

group.

Certain school rules pertain specifically to certain age groups. For instance, no one else may ride a San child's bicycle, and only Shack and Carriage children are allowed to build camp fires. The rules concerning when children must go to bed are also made according to age group.

Bedrooms generally accommodate four or five children.

Houseparents

Each of the boarding houses (save the Carriages, see below) has a "houseparent": a member of staff whose duty is pastoral care. The duties of a houseparent include doing their charges' laundry,

treating minor injuries and ailments, taking them to the doctor's

surgery or hospital for more serious complaints and general emotional

support. Depending on the age group, they might also tell them bedtime

stories, keep their valuables secure, escort them into town to spend

their pocket money, or speak on their behalf in the meetings.

San

Ages 6–8 (approx)

The San building is an outbuilding, near the primary classrooms;

its name derives from the fact that it was originally built as a sanatorium.

When there proved to be insufficient demand for a separate sanatorium,

it was given over to accommodation for the youngest children and their

houseparent. At one time, San children were housed in the main school

building, and the San building was used as the library. They have since

moved back, and the rooms they previously occupied now house the Cottage

children.

The laws of the school generally protect San children, both by

disallowing them from engaging in certain dangerous activities and

preventing older children from bullying, swindling or otherwise abusing

their juniors. San children have the right to bring up their cases at

the beginning of the school meeting or have another student or a teacher

bring the issue or issues up on their behalf.

San children can sleep in mixed-sex rooms, while older children have single-sex rooms.

Cottage

Ages 9–10 (approx)

Cottage children were originally housed in Neill's old cottage,

at the edge of the school grounds. For some time, the San wholly

replaced the Cottage, but Cottage children are now housed in the main

school building.

House

Ages 12–13 (approx)

House children are accommodated in the main school building, called simply "the House".

Shack

Ages 13–14 (approx)

The Shack buildings (there are two, the Boys' Shack and the

Girls' Shack) are small outbuildings, so called because of the somewhat

ramshackle nature of their original construction. The buildings have

since been renovated.

Children of Shack age and above are expected to take a more

active role in running the school, standing for committees, chairing the

meetings, acting as ombudsmen to resolve disputes and speaking in the

school meetings. Of course, younger children can take on some of these

roles if they so wish, and few of them are compulsory, even for the

older children. The only compulsory role is to be added to a rotation to

supervise work fines.

Carriages

Ages 15+ (approx)

The carriage buildings are similar to those of the Shack, only

larger. However, they were originally converted rail carriages. Since

the last renovation, the Boys' Carriage building incorporates a kitchenette and the Girls' Carriages a common room and shower block (other bathrooms in the school have only baths). Either facility may be used by both sexes.

The Carriage children each have individual rooms. They are

expected to do their own laundry and generally look after themselves.

This is not to say that they have no houseparent, just that as part of

their increased freedom they must take on additional responsibility.

Conflict resolution

There are two main methods of resolving conflicts at Summerhill.

Ombudsmen

In the first instance, one should go to an ombudsman

to resolve a conflict. The ombudsmen are an elected committee of older

members of the community, whose job it is to intervene in disputes. One

party will go and find an ombudsman and ask for an "Ombudsman Case".

Often, all the ombudsman has to do is warn someone to stop causing a

nuisance. Sometimes, if the dispute is more complex, the ombudsman must

mediate. If the conflict cannot be resolved there and then, or the

ombudsman's warnings are ignored, the case can be brought before the

school meeting.

In special cases, the meeting sometimes assigns an individual

their own "special ombudsman", an ombudsman who only takes cases from

one person. This usually happens if a particular child is being

consistently bullied, or has problems with the language (in which case

someone who is bilingual, in English and the language of the child in question, is chosen as the ombudsman.)

The tribunal

The

tribunal is the school meeting which concerns itself with people who

break the school rules. Sometimes there is a separate meeting for the

tribunal, and sometimes the legislative and judicial meetings are

combined. This is itself a matter which can be decided by the meeting.

A "tribunal case" consists of one person "bringing up" another,

or a group of people. The person bringing the case states the problem,

the chairperson asks those accused if they did it, and if they have

anything to say, then calls for any witnesses. If the accused admits to

the offence, or there are reliable witness statements, the chair will

call for proposals. Otherwise, the floor is opened to discussion.

If there is no clear evidence as to who is guilty (for instance,

in the case of an unobserved theft), the "investigation committee" is

often called upon. The investigation committee has the power to search

people's rooms or lockers, and to question people. They will bring the

case back to the next meeting if they are able to obtain any new

evidence. In a community as small as Summerhill, few events go totally

unnoticed and matters are usually resolved quickly.

Once it has been established that a person has broken the rules,

the meeting must propose and then vote to decide a fine. There is no

such thing as a 'standard fine', no equivalent to a judge's sentencing guidelines,

and most fines are given with consideration to the factors involved,

such as severity of the offence, intent behind the action, consequences

to others, remorse and/or behaviour displayed during the meeting, and

whether it was a repeat offence. Fines can include a "strong warning"

administered by the chair, a monetary fine, loss of privileges (for

instance, not being allowed out of school, or being the last to be

served lunch), or a "work fine" (e.g., picking up litter for a set time

or similar job of benefit to the community). In the case of theft, it is

usually considered sufficient for the thief to return what was stolen.

Although there are some rare cases where the property stolen is no

longer in the possession of the thief; in these cases, the thief is

given a more severe fine and is questioned as to where the property has

been sent.

Notoriety and criticism

Summerhill

received most of its public attention in two waves: the 1920s/30s and

1960s/70s. In particular, the 1960 American edition of Neill's writings,

Summerhill, made the school into an example for a wide public, and led to an American movement with copycat schools.

A. S. Neill's biographer Richard Bailey linked this increased interest

to the wider society's interest in social change (progressivism and the

counterculture, respectively), though he added that Neill was not

influenced by this reception.

Richard Bailey argued that the students' free choice of what to

learn may leave them unexposed to subject matter which they do not know

to exist, and also may narrow their exposure to subjects fashionable in a

given time period. The school has said it now has mechanisms in place to alleviate such concerns.

Bailey reviews an account of an algebra

lesson taught by Neill, and describes Neill's teaching technique as

"simply awful", for his lack of pupil engagement, inarticulate

explanations, and insults directed at pupils.

Bailey criticised Neill's avoidance of responsibility for his pupils'

academic performance, and his view that charismatic instruction was a

form of persuasion that weakened child autonomy.

Bailey also did find, however, that the media were unreasonably

critical in their coverage of the school. For instance they tended to

emphasize casual teacher–pupil relations and lack of compulsory classes,

instead of the weekly meeting. They also represented Summerhill's

pupils as unrestricted and anarchic, to an unrealistic degree.

Sexual licence

Mikey

Cuddihy, a graduate of Summerhill, wrote that in the 1960s: "It was

common for students to get married in mock weddings, and they were

allowed to sleep together...More worryingly, sexual relations

between students and teachers were also common...Neill's 35-year-old

stepson Myles, who taught pottery...went out with some of the more

senior pupils (because) he has a special dispensation."

In his book Summerhill (1960), Neill shows an influence of Wilhelm Reich's

theories, e.g., promoting adolescent sexual activity, and claiming that

a negative attitude towards masturbation causes juvenile delinquency.

Although Neill was not a trained psychotherapist, he held amateur

psychoanalytic sessions with some of his children. These sessions were

designed to "unblock" the "energies" of the children. For this purpose

Neill also gave body massages to the children, a technique advocated by Reich. In Summerhill, Neill gave accounts of such psychoanalytic sessions.

Neill wrote that "Promiscuity is neurotic; it is a constant

change of partner in the hope of finding the right partner at last.

[...] If the term free love has a sinister meaning, it is because it describes sex that is neurotic."

Notable former pupils

- John Burningham, children's author and illustrator

- Keith Critchlow, artist and professor of architecture

- Rebecca De Mornay, actress

- Storm Thorgerson, rock album cover designer

- Gus Dudgeon, record producer

In fiction and television

Enid Blyton's The Naughtiest Girl

series of novels, written in the 1940s and 50s, were her first series

about school-aged children, and they were set in a school based on

Summerhill, with democratic community meetings allowing the children to

make decisions about the school and 'punishments' etc.

Ira Levin's novel Rosemary's Baby (1967) has the main character reading a copy of Neill's book Summerhill and discussing it with her friends.

The school was the subject of the 1987 ITV documentary Being Happy is What Matters Most. This was later parodied in the 1997 Channel 4 documentary show Brass Eye in its second episode, "Drugs". The fictional documentary entitled The Drumlake Experiment featured an interview with the school's headmaster, Donaldus Matthews, played by David Cann.

In 1991 Zoe Readhead made an extended appearance on the Channel 4 discussion programme After Dark alongside among others the 13-year old James Harries.

In 1992, Channel 4's documentary show Cutting Edge created an episode on Summerhill at 70, broadcast on 30 March.

In 2008 BBC1, CBBC and BBC Four aired a miniseries called Summerhill.

The show was set in Summerhill and presented a highly fictionalised

version of the 2000 court case and the events leading up to it. Much of

the production was recorded on location at Summerhill and used pupils as

extras. The production presented an unabashedly positive view of the

school as the Director, Jon East, wanted to challenge the present paradigm of what a school is, as presented in popular culture. It received two BAFTAs, including one for script, by Alison Hume