| Hyperkinesia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Hyperkinesis |

| |

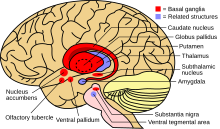

| Basal ganglia and its normal pathways. This circuitry is often disrupted in hyperkinesia. | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

Hyperkinesia refers to an increase in muscular activity that can result in excessive abnormal movements, excessive normal movements, or a combination of both. Hyperkinesia is a state of excessive restlessness which is featured in a large variety of disorders that affect the ability to control motor movement, such as Huntington's disease. It is the opposite of hypokinesia, which refers to decreased bodily movement, as commonly manifested in Parkinson's disease.

Many hyperkinetic movements are the result of improper regulation of the basal ganglia–thalamocortical circuitry. Overactivity of a direct pathway combined with decreased activity of indirect pathway results in activation of thalamic neurons and excitation of cortical neurons, resulting in increased motor output. Often, hyperkinesia is paired with hypotonia, a decrease in muscle tone. Many hyperkinetic disorders are psychological in nature and are typically prominent in childhood. Depending on the specific type of hyperkinetic movement, there are different treatment options available to minimize the symptoms, including different medical and surgical therapies. The word hyperkinesis comes from the Greek hyper, meaning "increased," and kinein, meaning "to move."

Classification

Basic hyperkinetic movements can be defined as any unwanted, excess movement. Such abnormal movements can be distinguished from each other on the basis of whether or not, or to what degree they are, rhythmic, discrete, repeated, and random. In evaluating the individual with a suspected form of hyperkinesia, the physician will record a thorough medical history, including a clear description of the movements in question, medications prescribed in the past and present, family history of similar diseases, medical history, including past infections, and any past exposure to toxic chemicals. Hyperkinesia is a defining feature of many childhood movement disorders, yet distinctly differs from both hypertonia and negative signs, which are also typically involved in such disorders. Several prominent forms of hyperkinetic movements include:

Ataxia

The term ataxia refers to a group of progressive neurological diseases that alter coordination and balance. Ataxias are often characterized by poor coordination of hand and eye movements, speech problems, and a wide-set, unsteady gait. Possible causes of ataxias may include stroke, tumor, infection, trauma, or degenerative changes in the cerebellum. These types of hyperkinetic movements can be further classified into two groups. The first group, hereditary ataxias, affect the cerebellum and spinal cord and are passed from one generation to the next through a defective gene. A common hereditary ataxia is Friedreich's ataxia. in contrast, sporadic ataxias occur spontaneously in individuals with no known family history of such movement disorders.

Athetosis

Athetosis is defined as a slow, continuous, involuntary writhing movement that prevents the individual from maintaining a stable posture. These are smooth, nonrhythmic movements that appear random and are not composed of any recognizable sub-movements. They mainly involve the distal extremities, but can also involve the face, neck, and trunk. Athetosis can occur in the resting state, as well as in conjunction with chorea and dystonia. When combined with o, as in cerebral palsy, the term "choreoathetosis" is frequently used.

Chorea

Chorea is a continuous, random-appearing sequence of one or more discrete involuntary movements or movement fragments. Although chorea consists of discrete movements, many are often strung together in time, thus making it difficult to identify each movement's start and end point. These movements can involve the face, trunk, neck, tongue, and extremities. Unlike dystonic movements, chorea-associated movements are often more rapid, random and unpredictable. Movements are repeated, but not rhythmic in nature. Children with chorea appear fidgety and will often try to disguise the random movements by voluntarily turning the involuntary, abnormal movement into a seemingly more normal, purposeful motion. Chorea may result specifically from disorders of the basal ganglia, cerebral cortex, thalamus, and cerebellum. It has also been associated with encephalitis, hyperthyroidism, anticholinergic toxicity, and other genetic and metabolic disorders. Chorea is also the prominent movement featured in Huntington's disease.

Dystonia

Dystonia is a movement disorder in which involuntarily sustained or intermittent muscle contractions cause twisting or repetitive movements, abnormal postures, or both. Such abnormal postures include foot inversion, wrist ulnar deviation, or lordotic trunk twisting. They can be localized to specific parts of the body or be generalized to many different muscle groups. These postures are often sustained for long periods of time and can be combined in time. Dystonic movements can augment hyperkinetic movements, especially when linked to voluntary movements.

Blepharospasm is a type of dystonia characterized by the involuntary contraction of the muscles controlling the eyelids. Symptoms can range from a simple increased frequency of blinking to constant, painful eye closure leading to functional blindness.

Oromandibular dystonia is a type of dystonia marked by forceful contractions of the lower face, which causes the mouth to open or close. Chewing motions and unusual tongue movements may also occur with this type of dystonia.

Laryngeal dystonia or spasmodic dysphonia results from abnormal contraction of muscles in the voice box, resulting in altered voice production. Patients may have a strained-strangled quality to their voice or, in some cases, a whispering or breathy quality.

Cervical dystonia (CD) or spasmodic torticollis is characterized by muscle spasms of the head and neck, which may be painful and cause the neck to twist into unusual positions or postures.

Writer's cramp and musician's cramp is a task-specific dystonia, meaning that it only occurs when performing certain tasks. Writer's cramp is a contraction of hand and/or arm muscles that happens only when a patient is writing. It does not occur in other situations, such as when a patient is typing or eating. Musician's cramp occurs only when a musician plays an instrument, and the type of cramp experienced is specific to the instrument. For example, pianists may experience cramping of their hands when playing, while brass players may have cramping or contractions of their mouth muscles.

Hemiballismus

Typically caused by damage to the subthalamic nucleus or nuclei, hemiballismus movements are nonrhythmic, rapid, nonsuppressible, and violent. They usually occur in an isolated body part, such as the proximal arm.

Hemifacial spasm

Hemifacial spasm (HFS) is characterized by involuntary contraction of facial muscles, typically occurring only on one side of the face. Like blepharospasm, the frequency of contractions in hemifacial spasm may range from intermittent to frequent and constant. The unilateral blepharospasm of HFS may interfere with routine tasks such as driving. In addition to medication, patients may respond well to treatment with Botox. HFS may be due to vascular compression of the nerves going to the muscles of the face. For these patients, surgical decompression may be a viable option for the improvement of symptoms.

Myoclonus

Myoclonus is defined as a sequence of repeated, often nonrhythmic, brief, shock-like jerks due to sudden involuntary contraction or relaxation of one or more muscles. These movements may be asynchronous, in which several muscles contract variably in time, synchronous, in which muscles contract simultaneously, or spreading, in which several muscles contract sequentially. It is characterized by a sudden, unidirectional movement due to muscle contraction, followed by a relaxation period in which the muscle is no longer contracted. However, when this relaxation phase is decreased, as when muscle contractions become faster, a myoclonic tremor results. Myoclonus can often be associated with seizures, delirium, dementia, and other signs of neurological disease and gray matter damage.

Stereotypies

Stereotypies are repetitive, rhythmic, simple movements that can be voluntarily suppressed. Like tremors, they are typically back and forth movements, and most commonly occur bilaterally. They often involve fingers, wrists, or proximal portions of the upper extremities. Although, like tics, they can stem from stress or excitement, there is no underlying urge to move associated with stereotypies and these movements can be stopped with distraction. When aware of the movements, the child can also suppress them voluntarily. Stereotypies are often associated with developmental syndromes, including the autism spectrum disorders. Stereotypies are quite common in preschool-aged children and for this reason are not necessarily indicative of neurological pathology on their own.

Tardive dyskinesia / tardive dystonia

Tardive dyskinesia or tardive dystonia, both referred to as "TD", refers to a wide variety of involuntary stereotypical movements caused by the prolonged use of dopamine receptor-blocking agents. The most common types of these agents are antipsychotics and anti-nausea agents. The classic form of TD refers to stereotypic movements of the mouth, which resemble chewing. However, TD can also appear as other involuntary movements such as chorea, dystonia, or tics.

Tics

A tic can be defined as a repeated, individually recognizable, intermittent movement or movement fragments that are almost always briefly suppressible and are usually associated with awareness of an urge to perform the movement. These abnormal movements occur with intervening periods of normal movement. These movements are predictable, often triggered by stress, excitement, suggestion, or brief voluntary suppressibility. Many children say that the onset of tics can stem from the strong urge to move. Tics can be either muscular (alter normal motor function) or vocal (alter normal speech) in nature and most commonly involve the face, mouth, eyes, head, neck or shoulder muscles. Tics can also be classified as simple motor tics (a single brief stereotyped movement or movement fragment), complex motor tics (a more complex or sequential movement involving multiple muscle groups), or phonic tics (including simple, brief phonations or vocalizations).

When both motor and vocal tics are present and persist for more than one year, a diagnosis of Tourette syndrome (TS) is likely. TS is an inherited neurobehavioral disorder characterized by both motor and vocal tics. Many individuals with TS may also develop obsessions, compulsions, inattention and hyperactivity. TS usually begins in childhood. Up to 5% of the population suffers from tics, but at least 20% of boys will have developed tics at some point in their lifetimes.

Tremor

A tremor can be defined as a rhythmic, back and forth or oscillating involuntary movement about a joint axis. Tremors are symmetric about a midpoint within the movement, and both portions of the movement occur at the same speed. Unlike the other hyperkinetic movements, tremors lack both the jerking associated movements and posturing.

Essential tremor (ET), also known as benign essential tremor, or familial tremor, is the most common movement disorder. It is estimated that 5 percent of people worldwide suffer from this condition, affecting those of all ages but typically staying within families. ET typically affects the hands and arms but can also affect the head, voice, chin, trunk and legs. Both sides of the body tend to be equally affected. The tremor is called an action tremor, becoming noticeable in the arms when they are being used. Patients often report that alcohol helps lessen the symptoms. Primary medical treatments for ET are usually beta-blockers. For patients who fail to respond sufficiently to medication, deep brain stimulation and thalamotomy can be highly effective.

A “flapping tremor,” or asterixis, is characterized by irregular flapping-hand movement, which appears most often with outstretched arms and wrist extension. Individuals with this condition resemble birds flapping their wings.

Volitional hyperkinesia

Volitional hyperkinesia refers to any type of involuntary movement described above that interrupts an intended voluntary muscular movement. These movements tend to be jolts that present suddenly during an otherwise smoothly coordinated action of skeletal muscle.

Pathophysiology

The causes of the majority of the above hyperkinetic movements can be traced to improper modulation of the basal ganglia by the subthalamic nucleus. In many cases, the excitatory output of the subthalamic nucleus is reduced, leading to a reduced inhibitory outflow of the basal ganglia. Without the normal restraining influence of the basal ganglia, upper motor neurons of the circuit tend to become more readily activated by inappropriate signals, resulting in the characteristic abnormal movements.

There are two pathways involving basal ganglia-thalamocortical circuitry, both of which originate in the neostriatum. The direct pathway projects to the internal globus pallidus (GPi) and to the substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr). These projections are inhibitory and have been found to utilize both GABA and substance P. The indirect pathway, which projects to the globus pallidus external (GPe), is also inhibitory and uses GABA and enkephalin. The GPe projects to the subthalamic nucleus (STN), which then projects back to the GPi and GPe via excitatory, glutaminergic pathways. Excitation of the direct pathway leads to disinhibition of the GABAergic neurons of the GPi/SNr, ultimately resulting in activation of thalamic neurons and excitation of cortical neurons. In contrast, activation of the indirect pathway stimulates the inhibitory striatal GABA/enkephalin projection, resulting in suppression of GABAerigc neuronal activity. This, in turn, causes disinhibition of the STN excitatory outputs, thus triggering the GPi/SNr inhibitory projections to the thalamus and decreased activation of cortical neurons. While deregulation of either of these pathways can disturb motor output, hyperkinesia is thought to result from overactivity of the direct pathway and decreased activity from the indirect pathway.

Hyperkinesia occurs when dopamine receptors, and norepinephrine receptors to a lesser extent, within the cortex and the brainstem are more sensitive to dopamine or when the dopaminergic receptors/neurons are hyperactive. Hyperkinesia can be caused by a large number of different diseases including metabolic disorders, endocrine disorders, heritable disorders, vascular disorders, or traumatic disorders. Other causes include toxins within the brain, autoimmune disease, and infections, which include meningitis.

Since the basal ganglia often have many connections with the frontal lobe of the brain, hyperkinesia can be associated with neurobehavioral or neuropsychiatric disorders such as mood changes, psychosis, anxiety, disinhibition, cognitive impairments, and inappropriate behavior.

In children, primary dystonia is usually inherited genetically. Secondary dystonia, however, is most commonly caused by dyskinetic cerebral palsy, due to hypoxic or ischemic injury to the basal ganglia, brainstem, cerebellum, and thalamus during the prenatal or infantile stages of development. Chorea and ballism can be caused by damage to the subthalamic nucleus. Chorea can be secondary to hyperthyroidism. Athetosis can be secondary to sensory loss in the distal limbs; this is called pseudoathetosis in adults but is not yet proven in children.

Diagnosis

Definition

There are various terms which refer to specific movement mechanisms that contribute to the differential diagnoses of hyperkinetic disorders.

As defined by Hogan and Sternad, “posture” is a nonzero time period during which bodily movement is minimal. When a movement is called “discrete,” it means that a new posture is assumed without any other postures interrupting the process. “Rhythmic” movements are those that occur in cycles of similar movements. “Repetitive,” “recurrent,” and “reciprocal” movements feature a certain bodily or joint position that occur more than once in a period, but not necessarily in a cyclic manner.

Overflow refers to unwanted movements that occur during a desired movement. It may occur in situations where the individual's motor intention spreads to either nearby or distant muscles, taking away from the original goal of the movement. Overflow is often associated with dystonic movements and may be due to a poor focusing of muscle activity and inability to suppress unwanted muscle movement. Co-contraction refers to a voluntary movement performed to suppress the involuntary movement, such as forcing one's wrist toward the body to stop it from involuntarily moving away from the body.

In evaluating these signs and symptoms, one must consider the frequency of repetition, whether or not the movements can be suppressed voluntarily (either by cognitive decisions, restraint, or sensory tricks), the awareness of the affected individual during the movement events, any urges to make the movements, and if the affected individual feels rewarded after having completed the movement. The context of the movement should also be noted; this means that a movement could be triggered in a certain posture, while at rest, during action, or during a specific task. The movement's quality can also be described in observing whether or not the movement can be categorized as a normal movement by an unaffected individual, or one that is not normally made on a daily basis by unaffected individuals.

Differential diagnosis

Diseases that feature one or more hyperkinetic movements as prominent symptoms include:

Huntington's disease

Hyperkinesia, more specifically chorea, is the hallmark symptom of Huntington's disease, formerly referred to as Huntington’s chorea. Appropriately, chorea is derived from the Greek word, khoros, meaning “dance.” The extent of the hyperkinesia exhibited in the disease can vary from solely the little finger to the entire body, resembling purposeful movements but occurring involuntarily. In children, rigidity and seizures are also symptoms. Other hyperkinetic symptoms include:

- Head turning to shift eye position

- Facial movements, including grimaces

- Slow, uncontrolled movements

- Quick, sudden, sometimes wild jerking movements of the arms, legs, face, and other body parts

- Unsteady gait

- Abnormal reflexes

- “prancing,” or a wide walk

The disease is characterized further by the gradual onset of defects in behavior and cognition, including dementia and speech impediments, beginning in the fourth or fifth decades of life. Death usually occurs within 10–20 years after a progressive worsening of symptoms. Caused by the Huntington gene, the disease eventually contributes to selective atrophy of the Caudate nucleus and Putamen, especially of GABAergic and acetylcholinergic neurons, with some additional degeneration of the frontal and temporal cortices of the brain. The disrupted signaling in the basal ganglia network is thought to cause the hyperkinesia. There is no known cure for Huntington's disease, yet there is treatment available to minimize the hyperkinetic movements. Dopamine blockers, such as haloperidol, tetrabenazine, and amantadine, are often effective in this regard.

Wilson's disease

Wilson's disease (WD) is a rare inherited disorder in which patients have a problem metabolizing copper. In patients with WD, copper accumulates in the liver and other parts of the body, particularly the brain, eyes and kidneys. Upon accumulation in the brain, patients may experience speech problems, incoordination, swallowing problems, and prominent hyperkinetic symptoms including tremor, dystonia, and gait difficulties. Psychiatric disturbances such as irritability, impulsiveness, aggressiveness, and mood disturbances are also common.

Restless leg syndrome

Restless leg syndrome is a disorder in which patients feel uncomfortable or unpleasant sensations in the legs. These sensations usually occur in the evening, while the patient is sitting or lying down and relaxing. Patients feel like they have to move their legs to relieve the sensations, and walking generally makes the symptoms disappear. In many patients, this can lead to insomnia and excessive daytime sleepiness. This is a very common problem and can occur at any age.

Similarly, the syndrome akathisia ranges from mildly compulsive movement usually in the legs to intense frenzied motion. These movements are partly voluntary, and the individual typically has the ability to suppress them for short amounts of time. Like restless leg syndrome, relief results from movement.

Post-stroke repercussions

A multitude of movement disorders have been observed after either ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. Some examples include athetosis, chorea with or without hemiballismus, tremor, dystonia, and segmental or focal myoclonus, although the prevalence of these manifestations after stroke is quite low. The amount of time that passes between stroke event and presentation of hyperkinesia depends on the type of hyperkinetic movement since their pathologies slightly differ. Chorea tends to affect older stroke victims while dystonia tends to affect younger ones. Men and women have an equal chance of developing the hyperkinetic movements after stroke. Strokes causing small, deep lesions in the basal ganglia, brain stem and thalamus are those most likely to be associated with post-stroke hyperkinesia.

Dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy

DRPLA is a rare trinucleotide repeat disorder (polyglutamine disease) that can be juvenile-onset (< 20 years), early adult-onset (20–40 years), or late adult-onset (> 40 years). Late adult-onset DRPLA is characterized by ataxia, choreoathetosis and dementia. Early adult-onset DRPLA also includes seizures and myoclonus. Juvenile-onset DRPLA presents with ataxia and symptoms consistent with progressive myoclonus epilepsy (myoclonus, multiple seizure types and dementia). Other symptoms that have been described include cervical dystonia, corneal endothelial degeneration, autism, and surgery-resistant obstructive sleep apnea.

Management

Athetosis, chorea and hemiballismus

Before prescribing medication for these conditions which often resolve spontaneously, recommendations have pointed to improved skin hygiene, good hydration via fluids, good nutrition, and installation of padded bed rails with use of proper mattresses. Pharmacological treatments include the typical neuroleptic agents such as fluphenazine, pimozide, haloperidol and perphenazine which block dopamine receptors; these are the first line of treatment for hemiballismus. Quetiapine, sulpiride and olanzapine, the atypical neuroleptic agents, are less likely to yield drug-induced parkinsonism and tardive dyskinesia. Tetrabenazine works by depleting presynaptic dopamine and blocking postsynaptic dopamine receptors, while reserpine depletes the presynaptic catecholamine and serotonin stores; both of these drugs treat hemiballismus successfully but may cause depression, hypotension and parkinsonism. Sodium valproate and clonazepam have been successful in a limited number of cases. Stereotactic ventral intermediate thalamotomy and use of a thalamic stimulator have been shown to be effective in treating these conditions.

Essential tremor

The medical treatment of essential tremor at the Movement Disorders Clinic at Baylor College of Medicine begins with minimizing stress and tremorgenic drugs along with recommending a restricted intake of beverages containing caffeine as a precaution, although caffeine has not been shown to significantly intensify the presentation of essential tremor. Alcohol amounting to a blood concentration of only 0.3% has been shown to reduce the amplitude of essential tremor in two-thirds of patients; for this reason it may be used as a prophylactic treatment before events during which one would be embarrassed by the tremor presenting itself. Using alcohol regularly and/or in excess to treat tremors is highly unadvisable, as there is a purported correlation between tremor and alcoholism. Alcohol is thought to stabilize neuronal membranes via potentiation of GABA receptor-mediated chloride influx. It has been demonstrated in essential tremor animal models that the food additive 1-octanol suppresses tremors induced by harmaline, and decreases the amplitude of essential tremor for about 90 minutes.

Two of the most valuable drug treatments for essential tremor are propranolol, a beta blocker, and primidone, an anticonvulsant. Propranolol is much more effective for hand tremor than head and voice tremor. Some beta-adrenergic blockers (beta blockers) are not lipid-soluble and therefore cannot cross the blood–brain barrier (propranolol being an exception), but can still act against tremors; this indicates that this drug's mechanism of therapy may be influenced by peripheral beta-adrenergic receptors. Primidone's mechanism of tremor prevention has been shown significantly in controlled clinical studies. The benzodiazepine drugs such as diazepam and barbiturates have been shown to reduce presentation of several types of tremor, including the essential variety. Controlled clinical trials of gabapentin yielded mixed results in efficacy against essential tremor while topiramate was shown to be effective in a larger double-blind controlled study, resulting in both lower Fahn-Tolosa-Marin tremor scale ratings and better function and disability as compared to placebo.

It has been shown in two double-blind controlled studies that injection of botulinum toxin into muscles used to produce oscillatory movements of essential tremors, such as forearm, wrist and finger flexors, may decrease the amplitude of hand tremor for approximately three months and that injections of the toxin may reduce essential tremor presenting in the head and voice. The toxin also may help tremor causing difficulty in writing, although properly adapted writing devices may be more efficient. Due to high incidence of side effects, use of botulinum toxin has only received a C level of support from the scientific community.

Deep brain stimulation toward the ventral intermediate nucleus of the thalamus and potentially the subthalamic nucleus and caudal zona incerta nucleus have been shown to reduce tremor in numerous studies. That toward the ventral intermediate nucleus of the thalamus has been shown to reduce contralateral and some ipsilateral tremor along with tremors of the cerebellar outflow, head, resting state and those related to hand tasks; however, the treatment has been shown to induce difficulty articulating thoughts (dysarthria), and loss of coordination and balance in long-term studies. Motor cortex stimulation is another option shown to be viable in numerous clinical trials.

Dystonia

Treatment of primary dystonia is aimed at reducing symptoms such as involuntary movements, pain, contracture, embarrassment, and to restore normal posture and improve the patient's function. This treatment is therefore not neuroprotective. According to the European Federation of Neurological Sciences and Movement Disorder Society, there is no evidence-based recommendation for treating primary dystonia with antidopaminergic or anticholinergic drugs although recommendations have been based on empirical evidence. Anticholinergic drugs prove to be most effective in treating generalized and segmental dystonia, especially if dose starts out low and increases gradually. Generalized dystonia has also been treated with such muscle relaxants as the benzodiazepines. Another muscle relaxant, baclofen, can help reduce spasticity seen in cerebral palsy such as dystonia in the leg and trunk. Treatment of secondary dystonia by administering levodopa in dopamine-responsive dystonia, copper chelation in Wilson's disease, or stopping the administration of drugs that may induce dystonia have been proven effective in a small number of cases. Physical therapy has been used to improve posture and prevent contractures via braces and casting, although in some cases, immobilization of limbs can induce dystonia, which is by definition known as peripherally induced dystonia. There are not many clinical trials that show significant efficacy for particular drugs, so medical of dystonia must be planned on a case-by-case basis. Botulinum toxin B, or Myobloc, has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat cervical dystonia due to level A evidential support by the scientific community. Surgery known as GPi DBS (Globus Pallidus Pars Interna Deep Brain Stimulation) has come to be popular in treating phasic forms of dystonia, although cases involving posturing and tonic contractions have improved to a lesser extent with this surgery. A follow-up study has found that movement score improvements observed one year after the surgery was maintained after three years in 58% of the cases. It has also been proven effective in treating cervical and cranial-cervical dystonia.

Tics

Treatment of tics present in conditions such as Tourette's syndrome begins with patient, relative, teacher and peer education about the presentation of the tics. Sometimes, pharmacological treatment is unnecessary and tics can be reduced by behavioral therapy such as habit-reversal therapy and/or counseling. Often this route of treatment is difficult because it depends most heavily on patient compliance. Once pharmacological treatment is deemed most appropriate, lowest effective doses should be given first with gradual increases. The most effective drugs belong to the neuroleptic variety such as monoamine-depleting drugs and dopamine receptor-blocking drugs. Of the monoamine-depleting drugs, tetrabenazine is most powerful against tics and results in fewest side effects. A non-neuroleptic drug found to be safe and effective in treating tics is topiramate. Botulinum toxin injection in affected muscles can successfully treat tics; involuntary movements and vocalizations can be reduced, as well as life-threatening tics that have the potential of causing compressive myelopathy or radiculopathy. Surgical treatment for disabling Tourette's syndrome has been proven effective in cases presenting with self-injury. Deep Brain Stimulation surgery targeting the globus pallidus, thalamus and other areas of the brain may be effective in treating involuntary and possibly life-threatening tics.

History

In the 16th century, Andreas Vesalius and Francesco Piccolomini were the first to distinguish between white matter, the cortex, and the subcortical nuclei in the brain. About a century later, Thomas Willis noticed that the corpus striatum was typically discolored, shrunken, and abnormally softened in the cadavers of people who had died from paralysis. The view that the corpus striatum played such a large role in motor functions was the most prominent one until the 19th century when electrophysiologic stimulation studies began to be performed. For example, Gustav Fritsch and Eduard Hitzig performed them on dog cerebral cortices in 1870, while David Ferrier performed them, along with ablation studies, on cerebral cortices of dogs, rabbits, cats, and primates in 1876. During the same year, John Hughlings Jackson posited that the motor cortex was more relevant to motor function than the corpus striatum after carrying out clinical-pathologic experiments in humans. Soon it would be discovered that the theory about the corpus striatum would not be completely incorrect.

By the late 19th century, a few hyperkinesias such as Huntington's chorea, post-hemiplegic choreoathetosis, Tourette's syndrome, and some forms of both tremor and dystonia were described in a clinical orientation. However, the common pathology was still a mystery. British neurologist William Richard Gowers called these disorders “general and functional diseases of the nervous system” in his 1888 publication entitled A Manual of Diseases of the Nervous System. It was not until the late 1980s and 1990s that sufficient animal models and human clinical trials were utilized to discover the specific involvement of the basal ganglia in the hyperkinesia pathology. In 1998, Wichmann and Delong made the conclusion that hyperkinesia is associated with decreased output from the basal ganglia, and in contrast, hypokinesia is associated with increased output from the basal ganglia. This generalization, however, still leaves a need for more complex models to distinguish the more nuanced pathologies of the numerous diverse hyperkinesias which are still being studied today.

In the 2nd century, Galen was the first to define tremor as “involuntary alternating up-and-down motion of the limbs.” Further classification of hyperkinetic movements came in the 17th and 18th centuries by Franciscus Sylvius and Gerard van Swieten. Parkinson's disease was one of the first disorders to be named as a result of the recent classification of its featured hyperkinetic tremor. The subsequent naming of other disorders involving abnormal motions soon followed.

Research directions

Studies have been done with electromyography to trace skeletal muscle activity in some hyperkinetic disorders. The electromyogram (EMG) of dystonia sometimes shows rapid rhythmic bursts, but these patterns can almost always be produced intentionally. In the myoclonus EMG, there are typically brief, and sometimes rhythmic, bursts or pauses in the recording pattern. When the bursts last for 50 milliseconds or less they are indicative of cortical myoclonus, but when they last up to 200 milliseconds, they are indicative of spinal or brainstem myoclonus. Such bursts can occur in multiple muscles simultaneously quite quickly, but high time resolution must be used in the EMG trace to clearly record them. The bursts recorded for tremor tend to be longer in duration than those of myoclonus, although some types can last for durations within the range for those of myoclonus. Future studies would have to examine the EMGs for tics, athetosis, stereotypies and chorea as there are minimal recordings done for those movements. However, it may be predicted that the EMG for chorea would include bursts varying in duration, timing, and amplitude, while that for tics and stereotypies would take on patterns of voluntary movements.

In general, research for treatment of hyperkinesia has most recently been focusing on ameliorating symptoms rather than attempting to correct the pathogenesis of the disease. Therefore, now and in the future it may be beneficial to inform the learning of the disease's pathology through carefully controlled, long-term, observation-based studies. As therapies are supported by proven effectiveness that can be repeated in multiple studies, they are useful, but the clinician may also consider that the best treatments for patients can only be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. It is the interplay of these two facets of neurology and medicine that may bring about significant progress in this field.