| Battle of Agincourt | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Hundred Years' War | |||||||

The Battle of Agincourt, 15th-century miniature, Enguerrand de Monstrelet | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

6,000–8,100 men • About 5⁄6 archers • 1⁄6 dismounted men-at-arms in heavy armour |

14,000–15,000 men or up to 25,000 if counting armed servants • 10,000 men-at-arms • 4,000–5,000 archers and crossbowmen • Up to 10,000 mounted and armed servants (gros valets) present | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Up to 600 killed (112 identified) |

• 6,000 killed (most of whom were of the French nobility) • 700–2,200 captured | ||||||

The Battle of Agincourt (/ˈædʒɪnkɔːr(t)/ AJ-in-kor(t); French: Azincourt [azɛ̃kuʁ]) was an English victory in the Hundred Years' War. It took place on 25 October 1415 (Saint Crispin's Day) near Azincourt, in northern France. The unexpected English victory against the numerically superior French army boosted English morale and prestige, crippled France and started a new period of English dominance in the war.

After several decades of relative peace, the English had resumed the war in 1415 amid the failure of negotiations with the French. In the ensuing campaign, many soldiers died from disease, and the English numbers dwindled; they tried to withdraw to English-held Calais but found their path blocked by a considerably larger French army. Despite the numerical disadvantage, the battle ended in an overwhelming victory for the English.

King Henry V of England led his troops into battle and participated in hand-to-hand fighting. King Charles VI of France did not command the French army as he suffered from psychotic illnesses and associated mental incapacity. The French were commanded by Constable Charles d'Albret and various prominent French noblemen of the Armagnac party. This battle is notable for the use of the English longbow in very large numbers, with the English and Welsh archers comprising nearly 80 percent of Henry's army.

Agincourt is one of England's most celebrated victories and was one of the most important English triumphs in the Hundred Years' War, along with the Battle of Crécy (1346) and Battle of Poitiers (1356). It forms the centrepiece of William Shakespeare's play Henry V, written in 1599.

Contemporary accounts

The Battle of Agincourt is well documented by at least seven contemporary accounts, three from eyewitnesses. The approximate location of the battle has never been disputed, and the site remains relatively unaltered after 600 years.

Immediately after the battle, Henry summoned the heralds of the two armies who had watched the battle together with principal French herald Montjoie, and they settled on the name of the battle as Azincourt, after the nearest fortified place. Two of the most frequently cited accounts come from Burgundian sources, one from Jean Le Fèvre de Saint-Remy who was present at the battle, and the other from Enguerrand de Monstrelet. The English eyewitness account comes from the anonymous author of the Gesta Henrici Quinti, believed to have been written by a chaplain in the King's household who would have been in the baggage train at the battle. A recent re-appraisal of Henry's strategy of the Agincourt campaign incorporates these three accounts and argues that war was seen as a legal due process for solving the disagreement over claims to the French throne.

Campaign

Henry V invaded France following the failure of negotiations with the French. He claimed the title of King of France through his great-grandfather Edward III of England, although in practice the English kings were generally prepared to renounce this claim if the French would acknowledge the English claim on Aquitaine and other French lands (the terms of the Treaty of Brétigny). He initially called a Great Council in the spring of 1414 to discuss going to war with France, but the lords insisted that he should negotiate further and moderate his claims. In the ensuing negotiations Henry said that he would give up his claim to the French throne if the French would pay the 1.6 million crowns outstanding from the ransom of John II (who had been captured at the Battle of Poitiers in 1356), and concede English ownership of the lands of Anjou, Brittany, Flanders, Normandy, and Touraine, as well as Aquitaine. Henry would marry Catherine, Charles VI's young daughter, and receive a dowry of 2 million crowns.

The French responded with what they considered the generous terms of marriage with Catherine, a dowry of 600,000 crowns, and an enlarged Aquitaine. By 1415, negotiations had ground to a halt, with the English claiming that the French had mocked their claims and ridiculed Henry himself. In December 1414, the English parliament was persuaded to grant Henry a "double subsidy", a tax at twice the traditional rate, to recover his inheritance from the French. On 19 April 1415, Henry again asked the Great Council to sanction war with France, and this time they agreed.

Henry's army landed in northern France on 13 August 1415, carried by a vast fleet. It was often reported to comprise 1,500 ships, but was probably far smaller. Theodore Beck also suggests that among Henry's army was "the king's physician and a little band of surgeons". Thomas Morstede, Henry V's royal surgeon, had previously been contracted by the king to supply a team of surgeons and makers of surgical instruments to take part in the Agincourt campaign. The army of about 12,000 men and up to 20,000 horses besieged the port of Harfleur. The siege took longer than expected. The town surrendered on 22 September, and the English army did not leave until 8 October. The campaign season was coming to an end, and the English army had suffered many casualties through disease. Rather than retire directly to England for the winter, with his costly expedition resulting in the capture of only one town, Henry decided to march most of his army (roughly 9,000) through Normandy to the port of Calais, the English stronghold in northern France, to demonstrate by his presence in the territory at the head of an army that his right to rule in the duchy was more than a mere abstract legal and historical claim. He also intended the manoeuvre as a deliberate provocation to battle aimed at the dauphin, who had failed to respond to Henry's personal challenge to combat at Harfleur.

During the siege, the French had raised an army which assembled around Rouen. This was not strictly a feudal army, but an army paid through a system similar to that of the English. The French hoped to raise 9,000 troops, but the army was not ready in time to relieve Harfleur.

After Henry V marched to the north, the French moved to block them along the River Somme. They were successful for a time, forcing Henry to move south, away from Calais, to find a ford. The English finally crossed the Somme south of Péronne, at Béthencourt and Voyennes and resumed marching north.

Without a river obstacle to defend, the French were hesitant to force a battle. They shadowed Henry's army while calling a semonce des nobles, calling on local nobles to join the army. By 24 October, both armies faced each other for battle, but the French declined, hoping for the arrival of more troops. The two armies spent the night of 24 October on open ground. The next day the French initiated negotiations as a delaying tactic, but Henry ordered his army to advance and to start a battle that, given the state of his army, he would have preferred to avoid, or to fight defensively: that was how Crécy and the other famous longbow victories had been won. The English had very little food, had marched 260 miles (420 km) in two and a half weeks, were suffering from sickness such as dysentery, and were greatly outnumbered by well-equipped French men-at-arms. The French army blocked Henry's way to the safety of Calais, and delaying battle would only further weaken his tired army and allow more French troops to arrive.

Setting

Battlefield

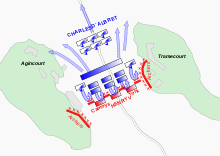

The precise location of the battle is not known. It may be in the narrow strip of open land formed between the woods of Tramecourt and Azincourt (close to the modern village of Azincourt). However, the lack of archaeological evidence at this traditional site has led to suggestions it was fought to the west of Azincourt. In 2019, the historian Michael Livingston also made the case for a site west of Azincourt, based on a review of sources and early maps.

English deployment

Early on the 25th, Henry deployed his army (approximately 1,500 men-at-arms and 7,000 longbowmen) across a 750-yard (690 m) part of the defile. The army was divided into three groups, with the right wing led by Edward, Duke of York, the centre led by the king himself, and the left wing under the old and experienced Baron Thomas Camoys. The archers were commanded by Sir Thomas Erpingham, another elderly veteran. It is likely that the English adopted their usual battle line of longbowmen on either flank, with men-at-arms and knights in the centre. They might also have deployed some archers in the centre of the line. The English men-at-arms in plate and mail were placed shoulder to shoulder four deep. The English and Welsh archers on the flanks drove pointed wooden stakes, or palings, into the ground at an angle to force cavalry to veer off. This use of stakes could have been inspired by the Battle of Nicopolis of 1396, where forces of the Ottoman Empire used the tactic against French cavalry.

The English made their confessions before the battle, as was customary. Henry, worried about the enemy launching surprise raids, and wanting his troops to remain focused, ordered all his men to spend the night before the battle in silence, on pain of having an ear cut off. He told his men that he would rather die in the coming battle than be captured and ransomed.

Henry made a speech emphasising the justness of his cause, and reminding his army of previous great defeats the kings of England had inflicted on the French. The Burgundian sources have him concluding the speech by telling his men that the French had boasted that they would cut off two fingers from the right hand of every archer, so that he could never draw a longbow again. Whether this was true is open to question; death was the normal fate of any soldier who could not be ransomed.

French deployment

The French army had 10,000 men-at arms plus some 4,000–5,000 miscellaneous footmen (gens de trait) including archers, crossbowmen (arbalétriers) and shield-bearers (pavisiers), totaling 14,000–15,000 men. Probably each man-at-arms would be accompanied by a gros valet (or varlet), an armed servant, adding up to another 10,000 potential fighting men, though some historians omit them from the number of combatants.

The French were organized into two main groups (or battles), a vanguard up front and a main battle behind, both composed principally of men-at-arms fighting on foot and flanked by more of the same in each wing. There was a special, elite cavalry force whose purpose was to break the formation of the English archers and thus clear the way for the infantry to advance. A second, smaller mounted force was to attack the rear of the English army, along with its baggage and servants. Many lords and gentlemen demanded – and got – places in the front lines, where they would have a higher chance to acquire glory and valuable ransoms; this resulted in the bulk of the men-at-arms being massed in the front lines and the other troops, for which there was no remaining space, to be placed behind. Although it had been planned for the archers and crossbowmen to be placed with the infantry wings, they were now regarded as unnecessary and placed behind them instead. On account of the lack of space, the French drew up a third battle, the rearguard, which was on horseback and mainly comprised the varlets mounted on the horses belonging to the men fighting on foot ahead.

The French vanguard and main battle numbered respectively 4,800 and 3,000 men-at-arms. Both lines were arrayed in tight, dense formations of about 16 ranks each, and were positioned a bowshot length from each other. Albret, Boucicaut and almost all the leading noblemen were assigned stations in the vanguard. The dukes of Alençon and Bar led the main battle. A further 600 dismounted men-at-arms stood in each wing, with the left under the Count of Vendôme and the right under the Count of Richemont. To disperse the enemy archers, a cavalry force of 800–1,200 picked men-at-arms, led by Clignet de Bréban and Louis de Bosredon, was distributed evenly between both flanks of the vanguard (standing slightly forward, like horns). Some 200 mounted men-at-arms would attack the English rear. The French apparently had no clear plan for deploying the rest of the army. The rearguard, leaderless, would serve as a "dumping ground" for the surplus troops.

Terrain

The field of battle was arguably the most significant factor in deciding the outcome. The recently ploughed land hemmed in by dense woodland favoured the English, both because of its narrowness, and because of the thick mud through which the French knights had to walk.

Accounts of the battle describe the French engaging the English men-at-arms before being rushed from the sides by the longbowmen as the mêlée developed. The English account in the Gesta Henrici says: "For when some of them, killed when battle was first joined, fall at the front, so great was the undisciplined violence and pressure of the mass of men behind them that the living fell on top of the dead, and others falling on top of the living were killed as well."

Although the French initially pushed the English back, they became so closely packed that they were described as having trouble using their weapons properly. The French monk of St. Denis says: "Their vanguard, composed of about 5,000 men, found itself at first so tightly packed that those who were in the third rank could scarcely use their swords," and the Burgundian sources have a similar passage.

Recent heavy rain made the battle field very muddy, proving very tiring to walk through in full plate armour. The French monk of St. Denis describes the French troops as "marching through the middle of the mud where they sank up to their knees. So they were already overcome with fatigue even before they advanced against the enemy". The deep, soft mud particularly favoured the English force because, once knocked to the ground, the heavily armoured French knights had a hard time getting back up to fight in the mêlée. Barker states that some knights, encumbered by their armour, actually drowned in their helmets.

Fighting

Opening moves

On the morning of 25 October, the French were still waiting for additional troops to arrive. The Duke of Brabant (about 2,000 men), the Duke of Anjou (about 600 men), and the Duke of Brittany (6,000 men, according to Monstrelet), were all marching to join the army.

For three hours after sunrise there was no fighting. Military textbooks of the time stated: "Everywhere and on all occasions that foot soldiers march against their enemy face to face, those who march lose and those who remain standing still and holding firm win." On top of this, the French were expecting thousands of men to join them if they waited. They were blocking Henry's retreat, and were perfectly happy to wait for as long as it took. There had even been a suggestion that the English would run away rather than give battle when they saw that they would be fighting so many French princes.

Henry's men were already very weary from hunger, illness and retreat. Apparently Henry believed his fleeing army would perform better on the defensive, but had to halt the retreat and somehow engage the French before a defensive battle was possible. This entailed abandoning his chosen position and pulling out, advancing, and then re-installing the long sharpened wooden stakes pointed outwards toward the enemy, which helped protect the longbowmen from cavalry charges. (The use of stakes was an innovation for the English: during the Battle of Crécy, for example, the archers had been instead protected by pits and other obstacles.)

The tightness of the terrain also seems to have restricted the planned deployment of the French forces. The French had originally drawn up a battle plan that had archers and crossbowmen in front of their men-at-arms, with a cavalry force at the rear specifically designed to "fall upon the archers, and use their force to break them," but in the event, the French archers and crossbowmen were deployed behind and to the sides of the men-at-arms (where they seem to have played almost no part, except possibly for an initial volley of arrows at the start of the battle). The cavalry force, which could have devastated the English line if it had attacked while they moved their stakes, charged only after the initial volley of arrows from the English. It is unclear whether the delay occurred because the French were hoping the English would launch a frontal assault (and were surprised when the English instead started shooting from their new defensive position), or whether the French mounted knights instead did not react quickly enough to the English advance. French chroniclers agree that when the mounted charge did come, it did not contain as many men as it should have; Gilles le Bouvier states that some had wandered off to warm themselves and others were walking or feeding their horses.

French cavalry attack

The French cavalry, despite being disorganised and not at full numbers, charged towards the longbowmen. It was a disastrous attempt. The French knights were unable to outflank the longbowmen (because of the encroaching woodland) and unable to charge through the array of sharpened stakes that protected the archers. John Keegan argues that the longbows' main influence on the battle at this point was injuries to horses: armoured only on the head, many horses would have become dangerously out of control when struck in the back or flank from the high-elevation, long-range shots used as the charge started. The mounted charge and subsequent retreat churned up the already muddy terrain between the French and the English. Juliet Barker quotes a contemporary account by a monk from St. Denis who reports how the wounded and panicking horses galloped through the advancing infantry, scattering them and trampling them down in their headlong flight from the battlefield.

Main French assault

The plate armour of the French men-at-arms allowed them to close the 1,000 yards or so to the English lines while being under what the French monk of Saint Denis described as "a terrifying hail of arrow shot". A complete coat of plate was considered such good protection that shields were generally not used, although the Burgundian contemporary sources distinguish between Frenchmen who used shields and those who did not, and Rogers has suggested that the front elements of the French force used axes and shields. Modern historians are divided on how effective the longbows would have been against plate armour of the time. Modern test and contemporary accounts conclude that arrows could not penetrate the better quality steel armour, which became available to knights and men-at-arms of fairly modest means by the middle of the 14th century, but could penetrate the poorer quality wrought iron armour. Rogers suggested that the longbow could penetrate a wrought iron breastplate at short range and penetrate the thinner armour on the limbs even at 220 yards (200 m). He considered a knight in the best-quality steel armour invulnerable to an arrow on the breastplate or top of the helmet, but vulnerable to shots hitting the limbs, particularly at close range. In any case, to protect themselves as much as possible from the arrows, the French had to lower their visors and bend their helmeted heads to avoid being shot in the face, as the eye- and air-holes in their helmets were among the weakest points in the armour. This head-lowered position restricted their breathing and their vision. Then they had to walk a few hundred yards (metres) through thick mud and a press of comrades while wearing armour weighing 50–60 pounds (23–27 kg), gathering sticky clay all the way. Increasingly, they had to walk around or over fallen comrades.

The surviving French men-at-arms reached the front of the English line and pushed it back, with the longbowmen on the flanks continuing to shoot at point-blank range. When the archers ran out of arrows, they dropped their bows and, using hatchets, swords and the mallets they had used to drive their stakes in, attacked the now disordered, fatigued and wounded French men-at-arms massed in front of them. The French could not cope with the thousands of lightly armoured longbowmen assailants (who were much less hindered by the mud and weight of their armour) combined with the English men-at-arms. The impact of thousands of arrows, combined with the slog in heavy armour through the mud, the heat and difficulty breathing in plate armour with the visor down, and the crush of their numbers, meant the French men-at-arms could "scarcely lift their weapons" when they finally engaged the English line. The exhausted French men-at-arms were unable to get up after being knocked to the ground by the English. As the mêlée developed, the French second line also joined the attack, but they too were swallowed up, with the narrow terrain meaning the extra numbers could not be used effectively. Rogers suggested that the French at the back of their deep formation would have been attempting to literally add their weight to the advance, without realising that they were hindering the ability of those at the front to manoeuvre and fight by pushing them into the English formation of lancepoints. After the initial wave, the French would have had to fight over and on the bodies of those who had fallen before them. In such a "press" of thousands of men, Rogers suggested that many could have suffocated in their armour, as was described by several sources, and which was also known to have happened in other battles.

The French men-at-arms were taken prisoner or killed in the thousands. The fighting lasted about three hours, but eventually the leaders of the second line were killed or captured, as those of the first line had been. The English Gesta Henrici described three great heaps of the slain around the three main English standards. According to contemporary English accounts, Henry fought hand to hand. Upon hearing that his youngest brother Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester had been wounded in the groin, Henry took his household guard and stood over his brother, in the front rank of the fighting, until Humphrey could be dragged to safety. The king received an axe blow to the head, which knocked off a piece of the crown that formed part of his helmet.

Attack on the English baggage train

The only French success was an attack on the lightly protected English baggage train, with Ysembart d'Azincourt (leading a small number of men-at-arms and varlets plus about 600 peasants) seizing some of Henry's personal treasures, including a crown. Whether this was part of a deliberate French plan or an act of local brigandage is unclear from the sources. Certainly, d'Azincourt was a local knight but he might have been chosen to lead the attack because of his local knowledge and the lack of availability of a more senior soldier. In some accounts the attack happened towards the end of the battle, and led the English to think they were being attacked from the rear. Barker, following the Gesta Henrici, believed to have been written by an English chaplain who was actually in the baggage train, concluded that the attack happened at the start of the battle.

Henry executes the French prisoners

Regardless of when the baggage assault happened, at some point after the initial English victory, Henry became alarmed that the French were regrouping for another attack. The Gesta Henrici places this after the English had overcome the onslaught of the French men-at-arms and the weary English troops were eyeing the French rearguard ("in incomparable number and still fresh"). Le Fèvre and Wavrin similarly say that it was signs of the French rearguard regrouping and "marching forward in battle order" which made the English think they were still in danger. A slaughter of the French prisoners ensued. It seems it was purely a decision of Henry, since the English knights found it contrary to chivalry, and contrary to their interests, to kill valuable hostages for whom it was commonplace to ask ransom. Henry threatened to hang whoever did not obey his orders.

In any event, Henry ordered the slaughter of what were perhaps several thousand French prisoners, sparing only the highest ranked (presumably those most likely to fetch a large ransom under the chivalric system of warfare). According to most chroniclers, Henry's fear was that the prisoners (who, in an unusual turn of events, actually outnumbered their captors) would realise their advantage in numbers, rearm themselves with the weapons strewn about the field and overwhelm the exhausted English forces. Contemporary chroniclers did not criticise him for it. In his study of the battle John Keegan argued that the main aim was not to actually kill the French knights but rather to terrorise them into submission and quell any possibility they might resume the fight, which would probably have caused the uncommitted French reserve forces to join the fray, as well. Such an event would have posed a risk to the still-outnumbered English and could have easily turned a stunning victory into a mutually destructive defeat, as the English forces were now largely intermingled with the French and would have suffered grievously from the arrows of their own longbowmen had they needed to resume shooting. Keegan also speculated that due to the relatively low number of archers actually involved in killing the French knights (roughly 200 by his estimate), together with the refusal of the English knights to assist in a duty they saw as distastefully unchivalrous, and combined with the sheer difficulty of killing such a large number of prisoners in such a short space of time, the actual number of French prisoners put to death may not have been substantial before the French reserves fled the field and Henry rescinded the order.

Aftermath

The French had suffered a catastrophic defeat. In all, around 6,000 of their fighting men lay dead on the ground. The list of casualties, one historian has noted, "read like a roll call of the military and political leaders of the past generation". Among them were 90–120 great lords and bannerets killed, including three dukes (Alençon, Bar and Brabant), nine counts (Blâmont, Dreux, Fauquembergue, Grandpré, Marle, Nevers, Roucy, Vaucourt, Vaudémont) and one viscount (Puisaye), also an archbishop. Of the great royal office holders, France lost its constable (Albret), an admiral (the lord of Dampierre), the Master of Crossbowmen (David de Rambures, dead along with three sons), Master of the Royal Household (Guichard Dauphin) and prévôt of the marshals. According to the heralds, 3,069 knights and squires were killed, while at least 2,600 more corpses were found without coats of arms to identify them. Entire noble families were wiped out in the male line, and in some regions an entire generation of landed nobility was annihilated. The bailiffs of nine major northern towns were killed, often along with their sons, relatives and supporters. In the words of Juliet Barker, the battle "cut a great swath through the natural leaders of French society in Artois, Ponthieu, Normandy, Picardy."

Estimates of the number of prisoners vary between 700 and 2,200, amongst them the dukes of Orléans and Bourbon, the counts of Eu, Vendôme, Richemont (brother of the Duke of Brittany and stepbrother of Henry V) and Harcourt, and marshal Jean Le Maingre.

While numerous English sources give the English casualties in double figures, record evidence identifies at least 112 Englishmen killed in the fighting, while Monstrelet reported 600 English dead. These included the Duke of York, the young Earl of Suffolk and the Welsh esquire Dafydd ("Davy") Gam.

Although the victory had been militarily decisive, its impact was complex. It did not lead to further English conquests immediately as Henry's priority was to return to England, which he did on 16 November, to be received in triumph in London on the 23rd. Henry returned a conquering hero, seen as blessed by God in the eyes of his subjects and European powers outside France. It established the legitimacy of the Lancastrian monarchy and the future campaigns of Henry to pursue his "rights and privileges" in France. Other benefits to the English were longer term. Very quickly after the battle, the fragile truce between the Armagnac and Burgundian factions broke down. The brunt of the battle had fallen on the Armagnacs and it was they who suffered the majority of senior casualties and carried the blame for the defeat. The Burgundians seized on the opportunity and within 10 days of the battle had mustered their armies and marched on Paris. This lack of unity in France allowed Henry eighteen months to prepare militarily and politically for a renewed campaign. When that campaign took place, it was made easier by the damage done to the political and military structures of Normandy by the battle.

Numbers at Agincourt

Most primary sources which describe the battle have English outnumbered by several times. By contrast, Anne Curry in her 2005 book Agincourt: A New History, argued, based on research into the surviving administrative records, that the French army was 12,000 strong, and the English army 9,000, proportions of four to three. While not necessarily agreeing with the exact numbers Curry uses, Bertrand Schnerb, a professor of medieval history at the University of Lille, states the French probably had 12,000–15,000 troops. Juliet Barker, Jonathan Sumption and Clifford J. Rogers criticized Curry's reliance on administrative records, arguing that they are incomplete and that several of the available primary sources already offer a credible assessment of the numbers involved. Ian Mortimer endorsed Curry's methodology, though applied it more liberally, noting how she "minimises French numbers (by limiting her figures to those in the basic army and a few specific additional companies) and maximises English numbers (by assuming the numbers sent home from Harfleur were no greater than sick lists)", and concluded that "the most extreme imbalance which is credible" is 15,000 French against 8,000–9,000 English. Barker opined that "if the differential really was as low as three to four then this makes a nonsense of the course of the battle as described by eyewitnesses and contemporaries".

Barker, Sumption and Rogers all wrote that the English probably had 6,000 men, these being 5,000 archers and 900–1,000 men-at-arms. These numbers are based on the Gesta Henrici Quinti and the chronicle of Jean Le Fèvre, the only two eyewitness accounts on the English camp. Curry and Mortimer questioned the reliability of the Gesta, as there have been doubts as to how much it was written as propaganda for Henry V. Both note that the Gesta vastly overestimates the number of French in the battle; its proportions of English archers to men-at-arms at the battle are also different from those of the English army before the siege of Harfleur. Mortimer also considers that the Gesta vastly inflates the English casualties – 5,000 – at Harfleur, and that "despite the trials of the march, Henry had lost very few men to illness or death; and we have independent testimony that no more than 160 had been captured on the way". Rogers, on the other hand, finds the number 5,000 plausible, giving several analogous historical events to support his case, and Barker considers that the fragmentary pay records which Curry relies on actually support the lower estimates.

Historians disagree less about the French numbers. Rogers, Mortimer and Sumption all give more or less 10,000 men-at-arms for the French, using as a source the herald of the Duke of Berry, an eyewitness. The number is supported by many other contemporary accounts. Curry, Rogers and Mortimer all agree the French had 4 to 5 thousand missile troops. Sumption, thus, concludes that the French had 14,000 men, basing himself on the monk of St. Denis; Mortimer gives 14 or 15 thousand fighting men. One particular cause of confusion may have been the number of servants on both sides, or whether they should at all be counted as combatants. Since the French had many more men-at-arms than the English, they would accordingly be accompanied by a far greater number of servants. Rogers says each of the 10,000 men-at-arms would be accompanied by a gros valet (an armed, armoured and mounted military servant) and a noncombatant page, counts the former as fighting men, and concludes thus that the French in fact numbered 24,000. Barker, who believes the English were outnumbered by at least four to one, says that the armed servants formed the rearguard in the battle. Mortimer notes the presence of noncombatant pages only, indicating that they would ride the spare horses during the battle and be mistakenly thought of as combatants by the English.

Popular representations

The battle remains an important symbol in popular culture. Some notable examples are listed below.

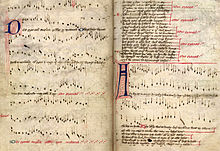

Music

Soon after the victory at Agincourt, a number of popular folk songs were created about the battle, the most famous being the "Agincourt Carol", produced in the first half of the 15th century. Other ballads followed, including "King Henry Fifth's Conquest of France", raising the popular prominence of particular events mentioned only in passing by the original chroniclers, such as the gift of tennis balls before the campaign.

Literature

The most famous cultural depiction of the battle today is in Act IV of William Shakespeare's Henry V, written in 1599. The play focuses on the pressures of kingship, the tensions between how a king should appear – chivalric, honest, and just – and how a king must sometimes act – Machiavellian and ruthless. Shakespeare illustrates these tensions by depicting Henry's decision to kill some of the French prisoners, whilst attempting to justify it and distance himself from the event. This moment of the battle is portrayed both as a break with the traditions of chivalry and as a key example of the paradox of kingship.

Shakespeare's depiction of the battle also plays on the theme of modernity. He contrasts the modern, English king and his army with the medieval, chivalric, older model of the French.

Shakespeare's play presented Henry as leading a truly English force into battle, playing on the importance of the link between the monarch and the common soldiers in the fight. The original play does not, however, feature any scenes of the actual battle itself, leading critic Rose Zimbardo to characterise it as "full of warfare, yet empty of conflict."

The play introduced the famous St Crispin's Day Speech, considered one of Shakespeare's most heroic speeches, which Henry delivers movingly to his soldiers just before the battle, urging his "band of brothers" to stand together in the forthcoming fight. Critic David Margolies describes how it "oozes honour, military glory, love of country and self-sacrifice", and forms one of the first instances of English literature linking solidarity and comradeship to success in battle. Partially as a result, the battle was used as a metaphor at the beginning of the First World War, when the British Expeditionary Force's attempts to stop the German advances were widely likened to it.

Shakespeare's portrayal of the casualty loss is ahistorical in that the French are stated to have lost 10,000 and the English 'less than' thirty men, prompting Henry's remark, "O God, thy arm was here".

Films

Shakespeare's version of the battle of Agincourt has been turned into several minor and two major films. The latter, each titled Henry V, star Laurence Olivier in 1944 and Kenneth Branagh in 1989. Made just prior to the invasion of Normandy, Olivier's rendition gives the battle what Sarah Hatchuel has termed an "exhilarating and heroic" tone, with an artificial, cinematic look to the battle scenes. Branagh's version gives a longer, more realist portrayal of the battle itself, drawing on both historical sources and images from the Vietnam and Falkland Wars.

In his 2007 film adaptation, director Peter Babakitis uses digital effects to exaggerate realist features during the battle scenes, producing a more avant-garde interpretation of the fighting at Agincourt. The battle also forms a central component of the 2019 Netflix film The King.

Mock trial

In March 2010, a mock trial of Henry V for the crimes associated with the slaughter of the prisoners was held in Washington, D.C., drawing from both the historical record and Shakespeare's play. Participating as judges were Justices Samuel Alito and Ruth Bader Ginsburg. The trial ranged widely over whether there was just cause for war and not simply the prisoner issue. Although an audience vote was "too close to call", Henry was unanimously found guilty by the court on the basis of "evolving standards of civil society".

Agincourt today

There is a modern museum in Agincourt village dedicated to the battle. The museum lists the names of combatants of both sides who died in the battle.