Retrofuturism (adjective retrofuturistic or retrofuture) is a movement in the creative arts showing the influence of depictions of the future produced in an earlier era. If futurism is sometimes called a "science" bent on anticipating what will come, retrofuturism is the remembering of that anticipation. Characterized by a blend of old-fashioned "retro styles" with futuristic technology, retrofuturism explores the themes of tension between past and future, and between the alienating and empowering effects of technology. Primarily reflected in artistic creations and modified technologies that realize the imagined artifacts of its parallel reality, retrofuturism can be seen as "an animating perspective on the world".

Etymology

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, an early use of the term appears in a Bloomingdales advertisement in a 1983 issue of The New York Times. The ad talks of jewellery that is "silverized steel and sleek grey linked for a retro-futuristic look". In an example more related to retrofuturism as an exploration of past visions of the future, the term appears in the form of “retro-futurist” in a 1984 review of the film Brazil in The New Yorker. Critic Pauline Kael writes, "[Terry Gilliam] presents a retro-futurist fantasy."

Several websites have referenced a supposed 1967 book published by Pelican Books called Retro-Futurism by T. R. Hinchliffe as the origin of the term, but this account is unverified. There exist no records of this book or author.

Historiography

Retrofuturism builds on ideas of futurism, but the latter term functions differently in several different contexts. In avant-garde artistic, literary and design circles, futurism is a long-standing and well established term. But in its more popular form, futurism (sometimes referred to as futurology) is "an early optimism that focused on the past and was rooted in the nineteenth century, an early-twentieth-century 'golden age' that continued long into the 1960s' Space Age".

Retrofuturism is first and foremost based on modern but changing notions of "the future". As Guffey notes, retrofuturism is "a recent neologism", but it "builds on futurists' fevered visions of space colonies with flying cars, robotic servants, and interstellar travel on display there; where futurists took their promise for granted, retro-futurism emerged as a more skeptical reaction to these dreams". It took its current shape in the 1970s, a time when technology was rapidly changing. From the advent of the personal computer to the birth of the first test tube baby, this period was characterized by intense and rapid technological change. But many in the general public began to question whether applied science would achieve its earlier promise—that life would inevitably improve through technological progress. In the wake of the Vietnam War, environmental depredations, and the energy crisis, many commentators began to question the benefits of applied science. But they also wondered, sometimes in awe, sometimes in confusion, at the scientific positivism evinced by earlier generations. Retrofuturism "seeped into academic and popular culture in the 1960s and 1970s", inflecting George Lucas's Star Wars and the paintings of pop artist Kenny Scharf alike". Surveying the optimistic futurism of the early twentieth century, the historians Joe Corn and Brian Horrigan remind us that retrofuturism is "a history of an idea, or a system of ideas—an ideology. The future, or course, does not exist except as an act of belief or imagination."

Characteristics

Retrofuturism incorporates two overlapping trends which may be summarized as the future as seen from the past and the past as seen from the future.

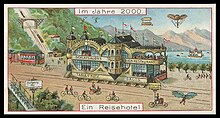

The first trend, retrofuturism proper, is directly inspired by the imagined future which existed in the minds of writers, artists, and filmmakers in the pre-1960 period who attempted to predict the future, either in serious projections of existing technology (e.g. in magazines like Science and Invention) or in science fiction novels and stories. Such futuristic visions are refurbished and updated for the present, and offer a nostalgic, counterfactual image of what the future might have been, but is not.

The second trend is the inverse of the first: futuristic retro. It starts with the retro appeal of old styles of art, clothing, mores, and then grafts modern or futuristic technologies onto it, creating a mélange of past, present, and future elements. Steampunk, a term applying both to the retrojection of futuristic technology into an alternative Victorian age, and the application of neo-Victorian styles to modern technology, is a highly successful version of this second trend. In the movie Space Station 76 (2014), mankind has reached the stars, but clothes, technology, furnitures and above all social taboos are purposely highly reminiscent of the mid-1970s.

In practice, the two trends cannot be sharply distinguished, as they mutually contribute to similar visions. Retrofuturism of the first type is inevitably influenced by the scientific, technological, and social awareness of the present, and modern retrofuturistic creations are never simply copies of their pre-1960 inspirations; rather, they are given a new (often wry or ironic) twist by being seen from a modern perspective.

In the same way, futuristic retro owes much of its flavor to early science fiction (e.g. the works of Jules Verne and H. G. Wells), and in a quest for stylistic authenticity may continue to draw on writers and artists of the desired period.

Both retrofuturistic trends in themselves refer to no specific time. When a time period is supplied for a story, it might be a counterfactual present with unique technology; a fantastic version of the future; or an alternate past in which the imagined (fictitious or projected) inventions of the past were indeed real.

The import of retrofuturism has, in recent years, come under considerable discussion. Some, like the German architecture critic Niklas Maak, see retrofuturism as "nothing more than an aesthetic feedback loop recalling a lost belief in progress, the old images of the once radically new". Bruce McCall calls retrofuturism a "faux nostalgia"—the nostalgia for a future that never happened.

Themes

Although retrofuturism, due to the varying time-periods and futuristic visions to which it alludes, does not provide a unified thematic purpose or experience, a common thread is dissatisfaction or discomfort with the present, to which retrofuturism provides a nostalgic contrast.

A similar theme is dissatisfaction with the modern world itself. A world of high-speed air transport, computers, and space stations is (by any past standard) "futuristic"; yet the search for alternative and perhaps more promising futures suggests a feeling that the desired or expected future has failed to materialize. Retrofuturism suggests an alternative path, and in addition to pure nostalgia, may act as a reminder of older but now forgotten ideals. This dissatisfaction also manifests as political commentary in Retrofuturistic literature, in which visionary nostalgia is paradoxically linked to a utopian future modelled after conservative values as seen in the example of Fox News' use of BioShock's aesthetic in a 2014 broadcast.

Retrofuturism also implies a reevaluation of technology. Unlike the total rejection of post-medieval technology found in most fantasy genres, or the embrace of any and all possible technologies found in some science-fiction, retrofuturism calls for a human-scale, largely comprehensible technology, amenable to tinkering and less opaque than modern black-box technology.

Retrofuturism is not universally optimistic, and when its points of reference touch on gloomy periods like World War II, or the paranoia of the Cold War, it may itself become bleak and dystopian. In such cases, the alternative reality inspires fear, not hope, though it may still be coupled with nostalgia for a world of greater moral as well as mechanical transparency.

Genres

Genres of retrofuturism include cyberpunk, steampunk, dieselpunk, atompunk, and Raygun Gothic, each referring to a technology from a specific time period.

The first of these to be named and recognized as its own genre was cyberpunk, originating in the early to mid-1980s in literature with the works of Bruce Bethke, William Gibson, Bruce Sterling, and Pat Cadigan. Its setting is almost always a dystopian future, with a strong emphasis either upon outlaws hacking the futuristic world's machinery (often computers and computer networks), or even upon post-apocalyptic settings. The post-apocalyptic variant is the one usually associated with retrofuturism, where characters will rely upon a mixture of old and new technologies. Furthermore, synthwave and vaporwave are nostalgic, humorous and often retrofuturistic revivals of early cyberpunk aesthetic.

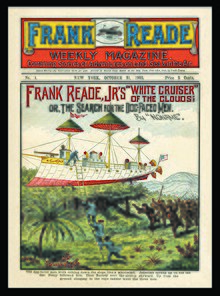

The second to be named and recognized was steampunk, in the late 1980s. It is generally more optimistic and brighter than cyberpunk, set within an alternate history closely resembling our Long 19th century from circa the Regency era onwards and up to circa 1914, only that 20th-century or even futuristic technologies are based upon steam power. The genre themes also often involve references to electricity as a yet-as-of-now mysterious force that is considered the utopian power source of the future and sometimes even regarded as possessing mystical healing powers (much as with nuclear energy around the middle of the 20th century). The genre often strongly resembles the original scientific romances and utopic novels of genre predecessors H. G. Wells and Jules Verne, and began in its modern form with literature such as Mervyn Peake's Titus Alone (1959), Ronald W. Clark's Queen Victoria's Bomb (1967), Michael Moorcock's A Nomad of the Time Streams series (1971–1981), K. W. Jeter's Morlock Night (1979), and William Gibson & Bruce Sterling's The Difference Engine (1990), and with films such as The Time Machine (1960) or Castle in the Sky (1986). A notable early example of steampunk in comics is the Franco-Belgian graphic novel series Les Cités obscures, started by its creators François Schuiten and Benoît Peeters in the early 1980s. At times, steampunk as a genre crosses into that of Weird West.

The most recently named and recognized retrofuturistic genre is dieselpunk aka decodence (the term dieselpunk is often associated with a more pulpish form and decodence, named after the contemporary art movement of Art Deco, with a more sophisticated form), set in alternate versions of an era located circa in the period of the 1920s–1950s. Early examples include the 1970s concept albums, their designs and marketing materials of the German band Kraftwerk (see below), the comic-book character Rocketeer (first appearing in his own series in 1982), the Fallout series of video games, and films such as Brazil (1985), Batman (1989), The Rocketeer (1991), Batman Returns (1992), The Hudsucker Proxy (1994), The City of Lost Children (1995), and Dark City (1998). Especially the lower end of the genre strongly mimic the pulp literature of the era (such as the 2004 film Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow), and films of the genre often reference the cinematic styles of film noir and German Expressionism. At times, the genre overlaps with the alternate history genre of a different World War II, such as with an Axis victory.

Design and arts

Although loosely affiliated with early-twentieth century Futurism, retrofuturism draws from a wider range of sources. To be sure, retrofuturist art and literature often draws from the factories, buildings, cities, and transportation systems of the machine age. But it might be said that 20th century futuristic vision found its ultimate expression in the development of Googie or Populuxe design. As applied to fiction, this brand of retrofuturistic visual style began to take shape in William Gibson's short story "The Gernsback Continuum". Here and elsewhere it is referred to as Raygun Gothic, a catchall term for a visual style that incorporates various aspects of the Googie, Streamline Moderne, and Art Deco architectural styles when applied to retrofuturistic science fiction environments.

Although Raygun Gothic is most similar to the Googie or Populuxe style and sometimes synonymous with it, the name is primarily applied to images of science fiction. The style is also still a popular choice for retro sci-fi in film and video games. Raygun Gothic's primary influences include the set designs of Kenneth Strickfaden and Fritz Lang. The term was coined by William Gibson in his story "The Gernsback Continuum": "Cohen introduced us and explained that Dialta [a noted pop-art historian] was the prime mover behind the latest Barris-Watford project, an illustrated history of what she called 'American Streamlined Modern'. Cohen called it 'raygun Gothic'. Their working title was The Airstream Futuropolis: The Tomorrow That Never Was."

Aspects of this form of retrofuturism can also be associated with the late 1970s and early 1980s the neo-Constructivist revival that emerged in art and design circles. Designers like David King in the UK and Paula Scher in the US imitated the cool, futuristic look of the Russian avant-garde in the years following the Russian Revolution.

With three of their 1970s albums, German band Kraftwerk tapped into a larger retrofuturist vision, by combining their futuristic pioneering electronic music with nostalgic visuals. Kraftwerk's retro-futurism in their 1970s visual language has been referred to by German literary critic Uwe Schütte, a reader at Aston University, Birmingham, as "clear retro-style", and in the 2008 three-hour documentary Kraftwerk and the Electronic Revolution, Irish-British music scholar Mark J. Prendergast refers to Kraftwerk's peculiar "nostalgia for the future" clearly referencing "an interwar [progressive] Germany that never was but could've been, and now [due to their influence as a band] hopefully could happen again". Design historian Elizabeth Guffey has written that if Kraftwerk's machine imagery was lifted from Russian design motifs that were once considered futuristic, they also presented a "compelling, if somewhat chilling, vision of the world in which musical ecstasy is rendered cool, mechanical and precise." Kraftwerk's three retrofuturist albums are:

- Kraftwerk's 1975 album Radio-Activity showed a contemporary 1930s radio on the cover, its inlay (which for its later CD re-release was widely expanded as a booklet illustrated in the same nostalgic style) showed the band photographed in black and white with old-fashioned suits and hairdos, and the music in its instrumentation as well as its ambiguous lyrics were (besides the other obvious theme of nuclear decay and nuclear power referenced by the album's titular pun) in hommage to the "Radio Stars", that is the pioneers of electronic music of the first half of the 20th century, such as Guglielmo Marconi, Léon Theremin, Pierre Schaeffer, and Karlheinz Stockhausen (due to whom the band referred to themselves as but the "second generation" of electronic music).

- The European version of the band's 1977 album Trans-Europe Express had a similar 1930s-style black and white photo of the band members on the cover (the U.S. version even had a cover of a vintage-style colored photograph in the style of Golden Age Hollywood stars), the style of the sleeve design as well as the design of promotional material tying in with the album were influenced by Bauhaus, Art Deco, and Streamline Moderne, the record came with a large, hand-tinted black and white poster of the band members in early-1930s style suits (where band member Karl Bartos later said in Kraftwerk and the Electronic Revolution that their intention was to visually resemble "an interwar string orchestra electrified" and that the background was meant to be a pictorial Switzerland where the band was making a resting stop in-between two legs of their European tour on the eponymous Trans-Europe Express), the song lyrics referenced the "elegance and decadence" of an urban interwar Europe, and in the promo clip made for the album's title song (shot in black and white on purpose) and other promotional material, the eponymous Trans-Europe Express was portrayed by the Schienenzeppelin first employed by the Deutsche Reichsbahn in 1931 (footage of the large original was used in outdoor shots, and a miniature model of it was used for shots where the TEE moved through a futuristic cityscape strongly reminiscent of Fritz Lang's 1927 film Metropolis).

- The cover and sleeve design of the 1978 album The Man-Machine exhibits an obvious stylistic nod to the Constructivism of 1920s artists such as El Lissitzky, Alexander Rodchenko, and László Moholy-Nagy (due to which band members have also referred to it as "the Russian album"), and one song references the film Metropolis again. From this album on, Kraftwerk would also use their "show-room dummies" aka robot lookalikes on stage and in promotional material and increase the use of slightly campish make-up on band members that also resembled 1920s' expressionist make-up that to a lesser degree had already appeared in the promotional material for their 1977 album Trans-Europe Express.

From their 1981 album Computer World onwards, Kraftwerk have largely abandoned their retro notions and appear mainly futuristic only. The only references to their earlier retro style today appear in excerpts from their 1970s' promo clips that are projected in between more modern segments in their stage shows during the performance of these old song.

Fashion

Retrofuturistic clothing is a particular imagined vision of the clothing that might be worn in the distant future, typically found in science fiction and science fiction films of the 1940s onwards, but also in journalism and other popular culture. The garments envisioned have most commonly been either one-piece garments, skin-tight garments, or both, typically ending up looking like either overalls or leotards, often worn together with plastic boots. In many cases, there is an assumption that the clothing of the future will be highly uniform.

The cliché of futuristic clothing has now become part of the idea of retrofuturism. Futuristic fashion plays on these now-hackneyed stereotypes, and recycles them as elements into the creation of real-world clothing fashions.

"We've actually seen this look creeping up on the runway as early as 1995, though it hasn't been widely popular or acceptable street wear even through 2008," said Brooke Kelley, fashion editor and Glamour magazine writer. "For the last 20 years, fashion has reviewed the times of past, decade by decade, and what we are seeing now is a combination of different eras into one complete look. Future fashion is a style beyond anything we've yet dared to wear, and it's going to be a trend setter's paradise."

Architecture

Retrofuturism has appeared in some examples of postmodern architecture. To critics such as Niklas Maak, the term suggests that the "future style" is "a mere quotation of its own iconographic tradition" and retrofuturism is little more than "an aesthetic feedback loop" In the example seen at right, the upper portion of the building is not intended to be integrated with the building but rather to appear as a separate object—a huge flying saucer-like space ship only incidentally attached to a conventional building. This appears intended not to evoke an even remotely possible future, but rather a past imagination of that future, or a reembracing of the futuristic vision of Googie architecture.

The once-futuristic Los Angeles International Airport Theme Building was built in 1961 as an expression of the then new jet and space ages, incorporating what later came to be known as Googie and Populuxe design elements. Plans unveiled in 2008 for LAX's expansion featured retrofuturist flying-saucer/spaceship themes in proposals for new terminals and concourses.

Video games

Retrofuturism has been also applied to video games, such as the following:

- Atomic Heart

- Alien: Isolation

- Assassin's Creed III

- BioShock

- Call of Duty: Black Ops II

- Command & Conquer: Red Alert

- Crimson Skies

- Cyberpunk 2077

- Cloudpunk

- Damnation

- Deathloop

- Dishonored

- Dishonored 2

- Dishonored: Death of the Outsider

- Fallout

- Far Cry 3: Blood Dragon

- Grim Fandango

- Grand Theft Auto 2

- Infamous Second Son

- Jazzpunk

- Metal Gear

- Observer

- Prey

- Resistance

- Stubbs the Zombie in Rebel Without a Pulse

- The Outer Worlds

- TimeShift

- Wasteland 2

- We Happy Few

- Wolfenstein

- X-COM: Apocalypse

- X-Men: Destiny

- Yu-Gi-Oh! Worldwide Edition: Stairway to the Destined Duel

Music

- Modern electro style, influenced by Detroit-based artist in the early 80s (such as Drexciya, Aux 88, Cybotron). This style blend old analog gear (Roland Tr-808 and synths) and sampling methods from the 80's with modern approach of electro. The records labels involved in this journey are AMZS Recording, Gosu, Osman, Traffic Records and many others.

- Canadian band Alvvays's music video, "Dreams Tonite", which includes archival footage of Montreal's Expo 67 was described by the band as "fetishizing retro-futurism".

- English band Electric Light Orchestra released their concept album "Time" in 1981. This album follows a man who wakes up in the year 2095 and how he reacts to this sudden change as well as his longing to be back in 1981. There are multiple descriptions of life and what technology is like in 2095.

Film

- Director Brad Bird describes his 2004 Pixar film The Incredibles as "looking like what we thought the future would turn out like in the 1960s."

- British filmmaker Richard Ayoade noted his film The Double from 2013 was designed with the intention of looking like "the future imagined by someone in the past who got it wrong."

- The 2015 Disney film Tomorrowland, which is based on Disneyland's attraction by the same name and also was directed by Brad Bird clearly has retrofuturistic aesthetic.