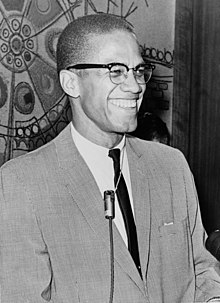

Malcolm X, March 1964

"The Ballot or the Bullet" is the title of a public speech by human rights activist Malcolm X. In the speech, which was delivered on April 3, 1964, at Cory Methodist Church in Cleveland, Ohio, Malcolm X advised African Americans

to judiciously exercise their right to vote, but he cautioned that if

the government continued to prevent African Americans from attaining

full equality, it might be necessary for them to take up arms. It was

ranked 7th in the top 100 American speeches of the 20th century by 137

leading scholars of American public address.

Background

Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam

On March 8, 1964, Malcolm X announced his separation from the Nation of Islam, a black nationalist religious organization for which he had been the spokesman for nearly a decade. The Nation of Islam, which advocated on behalf of African Americans, had significant disagreements with the Civil Rights Movement. Whereas the Civil Rights Movement advocated on behalf of integration and against segregation, the Nation of Islam favored separatism. One of the goals of the Civil Rights Movement was to end disenfranchisement of African Americans, but the Nation of Islam forbade its members from participating in the political process.

When he left the Nation of Islam, Malcolm declared his willingness to cooperate with the Civil Rights Movement.

He reassured leaders of the Civil Rights Movement that "I've forgotten

everything bad that [they] have said about me, and I pray they can also

forget the many bad things I've said about them."

The Civil Rights Act of 1964

In June 1963, President John F. Kennedy sent Congress

a civil rights bill. The bill proposed a ban on discrimination based on

race, religion, sex, or national origin in jobs and public

accommodations. Southern Democrats, sometimes called Dixiecrats, blocked the bill from consideration by the House of Representatives.

After Kennedy's assassination in November 1963, President Lyndon B. Johnson threw his support behind the civil rights bill. The bill was passed by the House on February 10, 1964, and sent to the Senate for consideration. Southern Democrats had promised to oppose the bill.

The speech

Malcolm

X began his speech by acknowledging that he was still a Muslim, but he

quickly added that he didn't intend to discuss religion or any other

issues that divide African Americans. Instead, he was going to emphasize

the common experience of African Americans of all faiths:

It's time for us to submerge our differences and realize that it is best for us to first see that we have the same problem, a common problem — a problem that will make you catch hell whether you're a Baptist, or a Methodist, or a Muslim, or a nationalist. Whether you're educated or illiterate, whether you live on the boulevard or in the alley, you're going to catch hell just like I am.

The ballot

Malcolm

X noted that 1964 was an election year, a year "when all of the white

political crooks will be right back in your and my community ... with

their false promises which they don't intend to keep".

He said that President Johnson and the Democratic Party claimed to

support the civil rights bill, and the Democrats controlled both the

House of Representatives and the Senate, but they had not taken genuine

action to pass the bill. Instead, he said, the Democrats blamed the

Dixiecrats, who were "nothing but Democrat[s] in disguise". He accused

the Democrats of playing a "political con game", with African Americans

as its victims.

Malcolm said that African Americans were becoming "politically

mature" and recognizing that, through unity and nonalignment, they could

be the swing vote in the coming elections and elect candidates who would be attentive to their concerns:

What does this mean? It means that when white people are evenly divided, and Black people have a bloc of votes of their own, it is left up to them to determine who's going to sit in the White House and who's going to be in the dog house.

Malcolm described how potent a weapon the ballot could be, if it was exercised with care:

A ballot is like a bullet. You don't throw your ballots until you see a target, and if that target is not within your reach, keep your ballot in your pocket.

The government

Although

he advocated exercising the ballot, Malcolm X expressed skepticism that

voting would bring about full equality for African Americans. The

government, he said, "is responsible for the oppression and exploitation

and degradation of Black people in this country.... This government has

failed the Negro".

According to Malcolm, one of the ways in which the government had

"failed the Negro" was its unwillingness to enforce the law. He pointed

out that the Supreme Court had outlawed segregation:

"Whenever you are going after something that is yours, you are within your legal rights to lay claim to it. And anyone who puts forth any effort to deprive you of that which is yours, is breaking the law, is a criminal. And this was pointed out by the Supreme Court decision. It outlawed segregation. Which means a segregationist is breaking the law".

But, he said, the police department and local government often sided with segregationists against the Civil Rights Movement.

Malcolm said that relying on the federal government to force

local governments to obey civil rights laws was futile. "When you take

your case to Washington, D.C., you're taking it to the criminal who's

responsible; it's like running from the wolf to the fox. They're all in

cahoots together".

Human rights

The proper solution, Malcolm X said, was to elevate the struggle of African Americans from one of civil rights to one of human rights.

A fight for civil rights was a domestic matter, and "no one from the

outside world can speak out in your behalf as long as your struggle is a

civil-rights struggle".

Malcolm said that changing the fight for African-American

equality to a human rights issue changed it from a domestic problem to

an international matter that could be heard by the United Nations.

He contrasted civil rights, which he described as "asking Uncle Sam to

treat you right", to human rights, which he called "your God-given

rights" and "the rights that are recognized by all nations of this

earth". He said that the people of the developing world

were "sitting there waiting to throw their weight on our side" if the

fight for civil rights were expanded into a human rights struggle.

Black nationalism

Malcolm X described his continued commitment to black nationalism,

which he defined as the philosophy that African Americans should govern

their own communities. He said that Black nationalists believe that

African Americans should control the politics and the economy in their

communities and that they need to remove the vices, such as alcoholism

and drug addiction, that afflict their communities.

Malcolm said that the philosophy of Black nationalism was being taught in the major civil rights organizations, including the NAACP, CORE, and SNCC.

Black nationalism was characterized by its political, social, and

economic philosophies. The political philosophy is self-government. The

local governments of the African-American communities should be managed

by African Americans. African Americans should be "re-educated into the

science of politics" in order to understand the importance and effect

of the vote they cast.

Don't be throwing out any ballots. A ballot is like a bullet. You don't throw your ballots until you see a target, and if that target is not within your reach, keep your ballot in your pocket.

The economic philosophy of black nationalism promotes

African-American control of the economy of the African-American

community. In frequenting stores not owned by an African American, the

money is given to another community. The dollar is taken from the

African-American community and given to outsiders. In doing so, the

African-American community loses money and becomes poorer while the

community the dollar was given to gains money and becomes richer.

Therefore, stores in the African-American community should be run by

African Americans.

Then you wonder why where you live is always a ghetto or a slum area. And where you and I are concerned, not only do we lose it when we spend it out of the community, but the white man has got all our stores in the community tied up; so that though we spend it in the community, at sundown the man who runs the store takes it over across town somewhere.

The social philosophy of black nationalism advocates for reform of

the community and reconstruction of it so it is more welcoming.

We ourselves have to lift the level of our community to a higher level, make our own society beautiful so that we will be satisfied in our own circles and won't be running around here try to knock our way into a social circle where we're not wanted.

Most of all, Malcolm promoted unity.

We've got to change our own minds about each other. We have to see each other with new eyes. We have to see each other as brothers and sisters. We have to come together with warmth so we can develop unity and harmony that's necessary to get this problem solved ourselves.

Self-defense

Malcolm

X addressed the issue of "rifles and shotguns", a controversy that had

dogged him since his March 8 announcement that he had left the Nation of

Islam.

He reiterated his position that if the government is "unwilling or

unable to defend the lives and the property of Negroes", African

Americans should defend themselves.

He advised his listeners to be mindful of the law — "This doesn't mean

you're going to get a rifle and form battalions and go out looking for

white folks ... that would be illegal and we don't do anything illegal" —

but he said that if white people didn't want African Americans to arm

themselves, the government should do its job.

The bullet

Malcolm

X referred to "the type of Black man on the scene in America today

[who] doesn't intend to turn the other cheek any longer", and warned that if politicians failed to keep their promises to African Americans, they made violence inevitable:

It's time now for you and me to become more politically mature and realize what the ballot is for; what we're supposed to get when we cast a ballot; and that if we don't cast a ballot, it's going to end up in a situation where we're going to have to cast a bullet. It's either a ballot or a bullet.

Malcolm predicted that if the civil rights bill wasn't passed, there would be a march on Washington in 1964. Unlike the 1963 March on Washington,

which was peaceful and integrated, the 1964 march Malcolm described

would be an all-Black "non-nonviolent army" with one-way tickets.

But, Malcolm said, there was still time to prevent this situation from developing:

Lyndon B. Johnson is the head of the Democratic Party. If he's for civil rights, let him go into the Senate next week and ... denounce the Southern branch of his party. Let him go in there right now and take a moral stand — right now, not later. Tell him, don't wait until election time. If he waits too long ... he will be responsible for letting a condition develop in this country which will create a climate that will bring seeds up out of the ground with vegetation on the end of them looking like something these people never dreamed of. In 1964, it's the ballot or the bullet.

Analysis

"The

Ballot or the Bullet" served several purposes at a critical point in

Malcolm X's life: it was part of his effort to distance himself from the

Nation of Islam, and it was intended to reach out to moderate civil

rights leaders. At the same time, the speech indicated that Malcolm

still supported Black nationalism and self-defense and thus had not made

a complete break with his past. "The Ballot or the Bullet" also marked a

notable shift in Malcolm X's rhetoric, as he presented previously

undiscussed ways of looking at the relationship between blacks and

whites.

Separation from the Nation of Islam

In

its advocacy of voting, "The Ballot or the Bullet" presented ideas

opposite to those of the Nation of Islam, which forbade its members from

participating in the political process.

Malcolm also chose not to discuss the religious differences that

divide Muslims and Christians, a common theme of his speeches when he

was the spokesman for the Nation of Islam. In "The Ballot or the

Bullet", Malcolm chose not to discuss religion but rather to stress the

experiences common to African Americans of all backgrounds.

Black nationalism

When

Malcolm X spoke of "the type of Black man on the scene in America today

[who] doesn't intend to turn the other cheek any longer",

he was addressing his followers, people who were not advocates of the

non-violent approach generally favored by the Civil Rights Movement.

Likewise, by stating his continued commitment to Black nationalism,

Malcolm reassured his followers that he had not made a complete break

with his past.

One biographer notes that Malcolm was one of the first

African-American leaders to note the existence and growing influence of

Black nationalism among young civil rights activists.

Rhetoric

"The

Ballot or the Bullet" indicates a shift in Malcolm X's rhetoric, as his

separation from the Nation of Islam and new, unfettered public activism

prompted a change in the ways he addressed his audience. Malcolm X

maintained his use of repetition as "communications of the passion that

is satisfied by a single statement, but that beats through the pulses",

and this can be exemplified by his consistent use of the phrase "the

ballot or the bullet". In addition, Malcolm X used his characteristic

use of language and imagery to disguise his conceptions of society and

history

in new ways to put issues into his perspective for his audience and

inspire activism. The most significant modification of Malcolm X's

rhetoric that can be observed in "The Ballot or the Bullet" is the

broadening of his audience, as he "emphasizes individualized judgement

rather than group cohesion" and allows for more analytical "flexibility restrained by a purposive focus on particular goals."

These changes expanded his appeal, therefore expanding his audience,

illustrating his ability to use the freedom he found after separating

from the Nation of Islam to his advantage in advancing himself as a

member of the Civil Rights Movement.