Rewilding is a form of ecological restoration aimed at increasing biodiversity and restoring natural processes. It differs from other forms of ecological restoration in that rewilding aspires to reduce human influence on ecosystems. It is also distinct from other forms of restoration in that, while it places emphasis on recovering geographically specific sets of ecological interactions and functions that would have maintained ecosystems prior to human influence, rewilding is open to novel or emerging ecosystems which encompass new species and new interactions.

A key feature of rewilding is its focus on replacing human interventions with natural processes. The aim is to create resilient, self-regulating and self-sustaining ecosystems.

While rewilding initiatives can be controversial, the United Nations has listed rewilding as one of several methods needed to achieve massive scale restoration of natural ecosystems, which they say must be accomplished by 2030 as part of the 30x30 campaign.

Origin

The term rewilding was coined by members of the grassroots network Earth First!, first appearing in print in 1990. It was refined and grounded in a scientific context in a paper published in 1998 by conservation biologists Michael Soulé and Reed Noss. Soulé and Noss envisaged rewilding as a conservation method based on the concept of 'cores, corridors, and carnivores'. Cores, corridors and carnivores (or the '3Cs') was based on the theory that large predators play regulatory roles in ecosystems. 3Cs rewilding therefore relied on protecting 'core' areas of wild land, linked together by 'corridors' allowing passage for 'carnivores' to move around the landscape and perform their functional role. The concept was developed further in 1999 and Earth First co-founder, Dave Foreman, subsequently wrote a full-length book on rewilding as a conservation strategy.

History

Rewilding was developed as a method to preserve functional ecosystems and reduce biodiversity loss, incorporating research in island biogeography and the ecological role of large carnivores. In 1967, The Theory of Island Biogeography by Robert H. MacArthur and Edward O. Wilson established the importance of considering the size and fragmentation of wildlife conservation areas, stating that protected areas remained vulnerable to extinctions if small and isolated. In 1987, William D. Newmark's study of extinctions in national parks in North America added weight to the theory. The publications intensified debates on conservation approaches. With the creation of the Society for Conservation Biology in 1985, conservationists began to focus on reducing habitat loss and fragmentation.

Practice and interest in rewilding grew rapidly in the first two decades of the 21st century. An early and groundbreaking initiative was led in the United Kingdom by Neil A. Hill, an ecologist and early proponent of non-interventional land management. His published work on the Landscape Enhancement Initiative (LEI) went on to inform a number of European projects under the Interreg IIIb tier. He undertook later work with the Iberian lynx that led to large-scale rewilding initiatives in the Dehesa/Montado ecosystems of the Iberian Peninsula. An early conceptual framework was further provided by Frans Vera's wood-pasture hypothesis, which hypothesizes a primary role for herbivores in shaping prehistoric European landscapes.

Supporters of rewilding initiatives range from individuals, small land owners, local non-governmental organizations and authorities, to national governments and international non-governmental organizations such as the International Union for Conservation of Nature. While small-scale efforts are generally well regarded the increased popularity of rewilding has generated controversy, especially regarding large-scale projects. These have sometimes attracted criticism from academics and practicing conservationists, as well as government officials and business people. In a 2021 report for the launch of the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration, the United Nations listed rewilding as one of several restoration methods which they state should be used for ecosystem restoration of over 1 billion hectares.

Guiding principles

Since its origin, the term rewilding has been used as a signifier of particular forms of ecological restoration projects (or advocacy thereof) that have ranged widely in scope and geographic application. In 2021 the journal Conservation Biology published a paper by 33 coauthors from around the world. Titled, 'Guiding Principles for Rewilding'. Researchers and project leaders from North America (Canada, Mexico and the United States) joined with counterparts in Europe (Denmark, France, Hungary, The Netherlands, Switzerland, and the UK), China, and South America (Chile and Colombia) to produce a unifying description, along with a set of ten guiding principles.

The group wrote, 'Commonalities in the concept of rewilding lie in its aims, whereas differences lie in the methods used, which include land protection, connectivity conservation, removing human infrastructure, and species reintroduction or taxon replacement.' Referring to the span of project types they stated, 'Rewilding now incorporates a variety of concepts, including Pleistocene megafauna replacement, taxon replacement, species reintroductions, retrobreeding, release of captive-bred animals, land abandonment, and spontaneous rewilding.'

Empowered by a directive from the International Union for the Conservation of Nature to produce a document on rewilding that reflected a global scale inventory of underlying goals as well as practices, the group sought a 'unifying definition', producing the following:

'Rewilding is the process of rebuilding, following major human disturbance, a natural ecosystem by restoring natural processes and the complete or near complete food web at all trophic levels as a self-sustaining and resilient ecosystem with biota that would have been present had the disturbance not occurred. This will involve a paradigm shift in the relationship between humans and nature. The ultimate goal of rewilding is the restoration of functioning native ecosystems containing the full range of species at all trophic levels while reducing human control and pressures. Rewilded ecosystems should—where possible—be self-sustaining. That is, they require no or minimal management (i.e., natura naturans [nature doing what nature does]), and it is recognized that ecosystems are dynamic.'

Ten principles were developed by the group:

- Rewilding utilizes wildlife to restore trophic interactions.

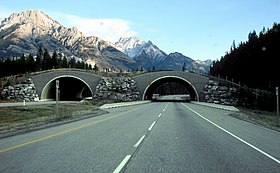

- Rewilding employs landscape-scale planning that considers core areas, connectivity, and co-existence.

- Rewilding focuses on the recovery of ecological processes, interactions, and conditions based on reference ecosystems.

- Rewilding recognizes that ecosystems are dynamic and constantly changing.

- Rewilding should anticipate the effects of climate change and where possible act as a tool to mitigate impacts.

- Rewilding requires local engagement and support.

- Rewilding is informed by science, traditional ecological knowledge, and other local knowledge.

- Rewilding is adaptive and dependent on monitoring and feedback.

- Rewilding recognizes the intrinsic value of all species and ecosystems.

- Rewilding requires a paradigm shift in the coexistence of humans and nature.

Rewilding and climate change

Rewilding can mitigate global climate change by restoring ecosystems. An example of this would be rewilding pasture land, thereby reducing the number of cows and sheep and increasing the number of trees.

Trophic rewilding can enhance the carbon capture and storage of ecosystems and has been posited as a "natural climate solution". The functional roles animals perform in an ecosystem, such as grazing, nutrient cycling and seed distribution, can influence the amount of carbon soils and plants capture in both marine and terrestrial environments. A study in a tropical forest in Guyana found that an increase in mammal species from 5 to 35 increased tree and soil carbon storage by four to five times, compared to an increase of 3.5 to four times with an increase of tree species from 10 to 70.

For example, the loss of wildebeest from the Serengeti led to an increase in ungrazed grass, leading to more frequent and intense fires, and causing the grassland to turn from a carbon sink into a carbon source. When disease management practices restored the population, the Serengeti returned to a carbon sink state.

Types of rewilding

Passive rewilding

Passive rewilding (also referred to as ecological rewilding) aims to restore natural ecosystem processes via minimal or the total withdrawal of direct human management of the landscape.

Active rewilding

Active rewilding is an umbrella term used to describe a range of rewilding approaches all of which involve human intervention. These might include species reintroductions or translocations and/or habitat engineering and the removal of man-made structures.

Trophic rewilding

Trophic rewilding is an ecological restoration strategy focussed on restoring trophic interactions (specifically top-down and associated trophic cascades where a top consumer/predator controls the primary consumer population) through species introductions, in order to promote self-regulating biodiverse ecosystems.

Pleistocene rewilding

Pleistocene rewilding is the advocacy of the reintroduction of extant Pleistocene megafauna, or the close ecological equivalents of extinct megafauna, to restore ecosystem function. Advocates of the approach maintain that communities where species evolved in response to Pleistocene megafauna (but now lack large mammals) may be in danger of collapse, while critics argue that it is unrealistic to assume that communities today are functionally similar to their state 10,000 years ago. European bison is one example of species reintroduced as part of Pleistocene rewilding in Europe and Britain.

Rewilding plants

In 1982 Daniel Janzen and Paul S. Martin originated the concept of evolutionary anachronism in a Science article titled, "Neotropical Anachronisms: The Fruits the Gomphotheres Ate". Eighteen years later Connie Barlow, in her book The Ghosts of Evolution: Nonsensical Fruit, Missing Partners, and Other Ecological Anachronisms (2000), explored the specifics of temperate North American plants whose fruits displayed the characteristics of megafauna dispersal syndrome. Barlow noted that a consequence for such native fruits following the loss of their megafaunal seed dispersal partners was range constriction during the Holocene, made increasingly severe since the mid-20th century by rapid human-driven climate change. Additional details of range contraction were incorporated in Barlow's 2001 article, "Anachronistic Fruits and the Ghosts Who Haunt Them".

A plant species beset with anachronistic features whose range had already become so restricted that it warranted endangered species classification was the glacial relict Torreya taxifolia. For this species, Barlow and Martin advocated assisted migration poleward in an article published in Wild Earth in 2004, titled "Bring Torreya taxifolia North Now". In 2005 Barlow and Lee Barnes (co-founders of Torreya Guardians) began obtaining seeds from mature horticultural plantings in states northward of Florida and Georgia for distribution to volunteer planters whose lands contained forested habitats potentially suitable for this native of Florida. Documentation of seed distribution and ongoing results, state by state, are publicly available on the Torreya Guardians website.) Articles published in Scientific American in 2009 and in Landscape Architecture Magazine in 2014 referred to the actions of Torreya Guardians as an example of "rewilding". Connie Barlow expressly referred to such efforts as "rewilding" in the 2020 book by Zach St. George, The Journeys of Trees. Her earliest use of the term "rewilding" was in her 1999 essay, "Rewilding for Evolution", in Wild Earth.

Because part of Barlow's activities occurred on public and private lands for which she did not expressly obtain planting permission, this form of rewilding action could be referred to as guerrilla rewilding, which is an adaptation of the established term guerrilla gardening. One example of guerrilla rewilding was reported in 2022. Himantoglossum robertianum is a tall orchid native to the Mediterranean Basin, but it is documented growing wild in Great Britain. As reported in The Guardian, "It is not believed these plants arrived naturally, but rather by someone scattering seeds about 15 years ago."

Within range, or slightly poleward of range, wild plantings are underway for a common subcanopy tree of the eastern United States. Pawpaw, Asimina triloba, is the northernmost species of an otherwise tropical fruit family, Annonaceae. Citizens in three states independently stepped forward to begin this rewilding effort in their home regions within Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Michigan. Because the fruit of pawpaw is regarded as an evolutionary anachronism, extinction of its coevolved seed dispersers (notably, mastodons) severely reduced its ability to obtain long-distance seed dispersal from any animals other than humans. Archeological evidence points to indigenous peoples of North America as fulfilling this function. That pawpaw planting sites chosen by citizens center on damaged riverine forests of old industrial sites in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and Ypsilanti, Michigan, may account for the lack of controversy regarding their actions.

While the intrinsic value of plants is an ethical foundation for many forms of plant conservation, the Pittsburgh wild-planting of pawpaw also entails an animal conservation ethic. Gabrielle Marsden is recruiting volunteers for the project she calls "Pittsburgh Pawpaw Pathways for Zebra Swallowtail Trails". Because the larval stage of the zebra swallowtail butterfly feeds only on pawpaw leaves, and because the butterfly is not a long-distance traveller, planting pawpaws within recovering forests on slopes of the Allegheny River is supported primarily as a way of expanding the population of the butterfly.

Elements

Rewilding aims to restore three key ecological processes: trophic complexity, dispersal, and stochastic disturbances.

Keystone species

A keystone species is a species that has a disproportionately large effect on its environment relative to its abundance.

Ecosystem engineers

One example of ecosystem engineers are powerful ground-disrupting animals that push over trees, trample shrubs and dig holes. These ensure that trees in grasslands do not become dominant. Some of these species used in rewilding efforts include beaver, elephants, bison, elk, cattle (as analogues for the extinct aurochs). These species also disperse seeds in their dung. Pig species, originally wild boar, dig creating soil where new plants can grow. Beavers are another important example of ecosystem engineers. The dams they build create micro-ecosystems that can be used as spawning beds for salmon and collect invertebrates for the salmon fry to feed on. The dams also create wetlands for plant, insect, and bird life. Specific trees, such as alder, birch, cottonwood, and willow, are important to beaver's diets and should be encouraged to grow in areas near beavers.

Predators

Predators may be required to ensure that browsing and grazing animals are kept from over-breeding/over-feeding, destroying vegetation complexity, as may be concluded from mass-starvations which happened in Oostvaardersplassen. Some examples of these predators are Eurasian lynx and wolves. However, although it is generally undebated that predators occupy an important role in ecosystems, there is no general agreement about whether wild predators keep herbivore populations in check, or whether their influence is of more subtle nature (see Ecology of fear). By analogy, wildebeest populations in the Serengeti are primarily controlled by food constraints despite the presence of many predators. The consequence is natural mass-starvation.

Criticism

Compatibility with economic activity

A view expressed by some national governments and officials within multilateral agencies such as the United Nations, is that excessive rewilding, such as large rigorously enforced protected areas where no extraction activities are allowed, can be too restrictive on people's ability to earn sustainable livelihoods. The alternative view is that increasing ecotourism can provide employment.

Farming

Some farmers have been critical of rewilding for 'abandoning productive farmland when the world's population is growing'. Farmers have also attacked plans to reintroduce the lynx in the United Kingdom because of fears that reintroduction will lead to an increase in sheep predation.

Conflicts with animal rights and welfare

Rewilding has been criticized by animal rights scholars, such as Dale Jamieson, who argues that "most cases of rewilding or reintroducing are likely to involve conflicts between the satisfaction of human preferences and the welfare of nonhuman animals." Erica von Essen and Michael Allen, using Donaldson and Kymlicka's political animal categories framework, assert that wildness standards imposed on animals are arbitrary and inconsistent with the premise that wild animals should be granted sovereignty over the territories that they inhabit and the right to make decisions about their own lives. To resolve this, von Essen and Allen contend that rewilding needs to shift towards full alignment with mainstream conservation and welcome full sovereignty, or instead take full responsibility for the care of animals who have been reintroduced. Ole Martin Moen argues that rewilding projects should be brought to an end because they unnecessarily increase wild animal suffering and are expensive, and the funds could be better spent elsewhere.

Erasure of environmental history

The environmental historian Dolly Jørgensen argues that rewilding, as it currently exists, 'seeks to erase human history and involvement with the land and flora and fauna. Such an attempted split between nature and culture may prove unproductive and even harmful.' She calls for rewilding to be more inclusive to combat this. Jonathan Prior and Kim J. Ward challenge Jørgensen's criticism and provide existing examples of rewilding programs which 'have been developed and governed within the understanding that human and non-human world are inextricably entangled'.

Harm to conservation

Some conservationists have expressed concern that rewilding 'could replace the traditional protection of rare species on small nature reserves', which could potentially lead to an increase in habitat fragmentation and species loss. David Nogués-Bravo and Carsten Rahbek assert that the benefits of rewilding lack evidence and that such programs may inadvertently lead to 'de-wilding', through the extinction of local and global species. They also contend that rewilding programs may draw funding away from 'more scientifically supported conservation projects'.

Rewilding in different locations

Both grassroots groups and major international conservation organizations have incorporated rewilding into projects to protect and restore large-scale core wilderness areas, corridors (or connectivity) between them, and apex predators, carnivores, or keystone species (species which interact strongly with the environment, such as elephant and beaver). Projects include the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative in North America (also known as Y2Y) and the European Green Belt, built along the former Iron Curtain, transboundary projects, including those in southern Africa funded by the Peace Parks Foundation, community-conservation projects, such as the wildlife conservancies of Namibia and Kenya, and projects organized around ecological restoration, including Gondwana Link, regrowing native bush in a hotspot of endemism in southwest Australia, and the Area de Conservacion Guanacaste, restoring dry tropical forest and rainforest in Costa Rica.

North America

In North America, a major project aims to restore the prairie grasslands of the Great Plains. The American Prairie is reintroducing bison on private land in the Missouri Breaks region of north-central Montana, with the goal of creating a prairie preserve larger than Yellowstone National Park.

Dam removal has led to the restoration of many river systems in the Pacific Northwest. This has been done in an effort to restore salmon populations specifically but with other species in mind. As stated in an article on environmental law, 'These dam removals provide perhaps the best example of large-scale environmental remediation in the twenty-first century. This restoration, however, has occurred on a case-by-case basis, without a comprehensive plan. The result has been to put into motion ongoing rehabilitation efforts in four distinct river basins: the Elwha and White Salmon in Washington and the Sandy and Rogue in Oregon.'

South America

Argentina

In 1997, Douglas and Kris Tompkins created 'The Conservation Land Trust Argentina', a team of conservationists and scientists with the goal of transforming the Iberá Wetlands. Thanks to the team and a donation of 195,094 ha (482,090 acres) of land made by Kris, in 2018 an area was converted into a National Park, and the jaguar was reintroduced into it, a species that had been extinct in the region for seven decades. They also introduced anteaters and giant otters. A spin-off of the Tompkins Foundation, Rewilding Argentina is an organization that is dedicated to the restoration of El Impenetrable National Park, in Chaco, Patagonia Park, in Santa Cruz, and the Patagonian coastal area in the province of Chubut, in addition to Iberá National Park.

Brazil

In Tijuca National Park (Rio de Janeiro state, Brazil), two important seed dispersers, the red-humped agouti and the brown howler monkey, were reintroduced between years 2010 and 2017. The goal of the reintroductions was to restore seed dispersal interactions between seed dispersing animals and fleshy-fruited trees. The agoutis and howler monkeys interacted with several plant and dung beetle species. Before reintroductions, the national park did not have large or intermediate -sized seed dispersers, meaning that the increased dispersal of tree seeds following the reintroductions can have a large effect on forest regeneration in the national park. The Tijuca National Park is part of heavily fragmented Atlantic Forest, where there is potential to restore many more seed dispersal interactions if seed dispersing mammals and birds are reintroduced to forest patches where the tree species diversity remains high.

Australia

Rewilding is newer in Australia than in Europe and North America, but there are many projects underway across the country as of 2023. Colonisation has had a huge impact on the native flora and fauna, and the introduction of red foxes and cats has devastated many of the smaller ground-dwelling mammals. The island state of Tasmania has become an important location for rewilding efforts because, as an island, it is easier to remove feral cat populations and manage other invasive species. The reintroduction and management of the Tasmanian devil in this state, and dingoes on the mainland, is being trialled in an effort to contain introduced predators, as well as over-populations of kangaroos.

WWF-Australia has a program called 'Rewilding Australia' which aims to 'test strategies to increase resilience and adaptability to these current and future threats'. Its projects include the platypus in the Royal National Park, south of Sydney, eastern quolls in the Booderee National Park in Jervis Bay and at Silver Plains in Tasmania, and brush-tailed bettongs in the Marna Banggara project on the Yorke Peninsula in South Australia. Other projects around the country include:

- Barrington Wildlife Sanctuary, NSW – many species

- Mongo Valley, NSW – koalas

- Bungador Stoney Rises Nature Reserve, Victoria – spotted-tail quoll, koala, long-nosed potoroo

- Mount Zero-Taravale Sanctuary, Queensland – several species

- Dirk Hartog Island National Park, Western Australia – many species

- Marna Banggara, SA – also red-tailed phascogales and bandicoots

- Clarke Island/Lungtalanana, Tasmania – several species

- Other locations around Tasmania - Tasmanian devils and (proposed) emus

Europe

In 2011, the 'Rewilding Europe' initiative was established with the aim of rewilding one million hectares of land in ten areas including the western Iberian Peninsula, Velebit, the Carpathians and the Danube delta by 2020, mostly abandoned farmland among other identified candidate sites. The present project considers only species that are still present in Europe, such as the Iberian lynx, Eurasian lynx, grey wolf, European jackal, brown bear, chamois, Iberian ibex, European bison, red deer, griffon vulture, cinereous vulture, Egyptian vulture, great white pelican and horned viper, along with a few primitive breeds of domestic horse/Przewalski's horse and cattle as proxies for the extinct tarpan and aurochs. Since 2012, Rewilding Europe has been heavily involved in the Tauros Programme, which seeks to create a breed of cattle that resembles the aurochs, the wild ancestors of domestic cattle, by selectively breeding existing breeds of cattle. Many projects also employ domestic water buffalo as a grazing analogue for the extinct European water buffalo.

Areas of rewilding include the Côa River, a Natura 2000 area. European Wildlife, established in 2008, advocates the establishment of a European Centre of Biodiversity at the German–Austrian–Czech borders, and the Chernobyl exclusion zone in Ukraine.

Austria

Der Biosphärenpark Wienerwald was created in Austria in 2003. Within this area 37 kernzonen (core zones) covering 5,400 ha in total were designated areas free from human interference.

Britain

Rewilding Britain, a charity founded in 2015, aims to promote rewilding in Britain and is a leading advocate of rewilding. Rewilding Britain has laid down 'five principles of rewilding' which it expects to be followed by affiliated rewilding projects. These are: 1. Support people and nature together, 2. Let nature lead, 3. Create resilient local economies, 4. Work at nature's scale, 5. Secure benefits for the long-term. In practice rewilding as effected by private landowners and managers takes many different forms, with emphases placed on varying aspects.

Celtic Reptile & Amphibian is a limited company established in 2020, with the aim of reintroducing extinct species of reptile and amphibian (such as the European pond turtle, moor frog, agile frog, common tree frog and pool frog) to Britain, as part of rewilding schemes. Success has already been achieved with the captive breeding of the moor frog. A reintroduction trial of the European pond turtle to its historic, Holocene range in the East Anglian Fens, Brecks and Broads has been initiated, with support from the University of Cambridge.

In 2020, nature writer Melissa Harrison reported a significant increase in attitudes supportive of rewilding among the British public, with plans recently approved for the release of European bison, Eurasian elk, and great bustard in England, along with calls to rewild as much as 20% of the land in East Anglia, and even return apex predators such as the Eurasian lynx, brown bear, and grey wolf. More recently, academic work on rewilding in England has highlighted that support for rewilding is by no means universal. As in other countries, rewilding in England remains controversial to the extent that some of its more ambitious aims are being 'domesticated' both in a proactive attempt to make it less controversial and in reactive response to previous controversy. Projects may also refer to their activity using terminology other than 'rewilding', possibly for political and diplomatic reasons, taking account of local sentiment or possible opposition. Examples include 'Sanctuary Nature Recovery Programme' (at Broughton) and 'nature restoration project', the preferred term used by the Cambrian Wildwood project, an area aspiring to encompass 7,000 acres in Wales.

Notable rewilding sites ' include:

- Knepp Castle. The 3,500 acre (1,400 hectare) Knepp Castle estate in West Sussex was the first major pioneer of rewilding in England, and started that land-management policy there in 2001 on land formerly used as dairy farmland. (See Knepp Wildland). Rare species including common nightingale, turtle doves, peregrine falcons and purple emperor butterflies are now breeding at Knepp and populations of more common species are increasing. In 2019 a pair of white storks built a nest in an oak tree at Knepp, part of a group imported from Poland, the result of a programme to re-introduce that species to England run by the Roy Dennis Wildlife Foundation, which has overseen reintroductions of other extinct bird species to the UK.

- Broughton Hall Estate, Yorkshire. In 2021 about 1,100 acres (a third of the estate) have been devoted to rewilding, with advice from Prof. Alastair Driver of Rewilding Britain.

- Mapperton Estate, Dorset, largely inspired by the work at Knepp. At Mapperton one of the five farms comprising the estate entered the process of re-wilding in 2021, accounting for 200 acres.

- Alladale Wilderness Reserve, Sutherland, Scotland. This 23,000 acre estate hosts many species of wildlife, and engages in rewilding projects such as peatland and forest restoration, captive breeding of the Scottish wildcat, and reintroduction of the red squirrel. Visitors can engage in outdoor recreation and engage in education programs.

The Netherlands

In the 1980s, the Dutch government began introducing analogue species in the Oostvaardersplassen nature reserve, an area covering over 56 square kilometres (22 sq mi), in order to recreate a grassland ecology. This happened in line with Vera's proposal that grazing animals played a significant role in the shaping of European landscapes before the Neolithic - the wood-pasture hypothesis. Though not explicitly referred to as rewilding many of the goals and intentions of the project were in line with those of rewilding. The reserve is considered somewhat controversial due to the lack of predators and other native megafauna such as wolves, bears, lynx, elk, boar, and wisent. Konik ponies were reintroduced together with Heck cattle and red deer to keep the landscape open by natural grazing. This provided habitat for geese who are key species in the wetlands of the area. The grazing of geese made it possible for reedbeds to remain and therefore conserved many protected birds species. This is a prime example how water and land ecosystems are connected and how reintroducing keystone species can conserve other protected species. However, management of the Oostvaardersplassen is to be regarded as one that has to contend with conflicting ideas as to nature and remains a debated area.