From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Gaddafi at the 12th African Union conference in 2009

After coming to power, the RCC government initiated a process of

directing funds toward providing education, health care and housing for

all. Public education in the country became free and primary education

compulsory for both sexes. Medical care became available to the public

at no cost, but providing housing for all was a task the RCC government

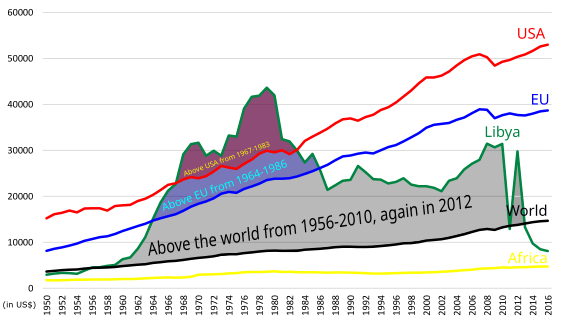

was not able to complete. Under Gaddafi, per capita income in the country rose to more than US $11,000, the fifth highest in Africa.

The increase in prosperity was accompanied by a controversial foreign

policy, and there was increased domestic political repression.

During the 1980s and 1990s, Gaddafi, in alliance with the

Eastern Bloc and

Fidel Castro's Cuba, openly supported rebel movements like

Nelson Mandela's African National Congress, the

Palestine Liberation Organization, the

Irish Republican Army and the

Polisario Front (

Western Sahara).

Gaddafi's government was either known to be or suspected of

participating in or aiding terrorist acts by these and other proxy

forces. Additionally, Gaddafi undertook several invasions of neighboring

states in Africa, notably

Chad in the 1970s and 1980s. All of his actions led to a deterioration of

Libya's foreign relations with several countries, mostly

Western states, and culminated in the

1986 United States bombing of Libya. Gaddafi defended his government's actions by citing the need to support

anti-imperialist and anti-colonial movements around the world. Notably, Gaddafi supported

anti-Zionist,

pan-Africanist and

black civil rights

movements. Gaddafi's behavior, often erratic, led some outsiders to

conclude that he was not mentally sound, a claim disputed by the Libyan

authorities and other observers close to Gaddafi. Despite receiving

extensive aid and technical assistance from the

Soviet Union and its allies, Gaddafi retained close ties to pro-American governments in

Western Europe, largely by

incentivising Western oil companies with promises of access to lucrative Libyan energy sectors. After the

9/11 attacks,

strained relations between Libya and the West were mostly normalised,

and sanctions against the country relaxed, in exchange for

Libyan efforts to shrink its nuclear program.

In early 2011,

a civil war broke out in the context of the wider "

Arab Spring". The rebel

anti-Gaddafi forces formed a committee named the

National Transitional Council on 27 February 2011. It was meant to act as an

interim authority in the rebel-controlled areas. After killings by government forces in addition to those by the rebel forces, a

multinational coalition led by

NATO forces intervened on 21 March 2011 in support of the rebels. The

International Criminal Court

issued an arrest warrant against Gaddafi and his entourage on 27 June

2011. Gaddafi's government was overthrown in the wake of the

fall of Tripoli

to the rebel forces on 20 August 2011, although pockets of resistance

held by forces in support of Gaddafi's government held out for another

two months, especially in Gaddafi's hometown of

Sirte, which he declared the new capital of Libya on 1 September 2011.

The fall of the last remaining cities under pro-Gaddafi control and

Sirte's capture on 20 October 2011, followed by the subsequent

killing of Gaddafi, marked the end of the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya.

The name of Libya was changed several times during Gaddafi's

tenure as leader. At first, the name was the Libyan Arab Republic. In

1977, the name was changed to

Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya.

Jamahiriya was a term coined by Gaddafi, usually translated as "state of the masses". The country was renamed again in 1986 as the

Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, after the

1986 United States bombing of Libya.

Coup d'état of 1969

The discovery of significant

oil reserves in 1959 and the subsequent income from

petroleum sales enabled the

Kingdom of Libya

to transition from one of the world's poorest nations to a wealthy

state. Although oil drastically improved the Libyan government's

finances, resentment began to build over the increased concentration of

the nation's wealth in the hands of the noble

King Idris. This discontent mounted with the rise of

Nasserism and

Arab nationalism/

socialism throughout North Africa and the Middle East.

On 1 September 1969, a group of about 70 young army officers

known as the Free Officers Movement and enlisted men mostly assigned to

the

Signal Corps, seized control of the government and in a stroke abolished the Libyan monarchy. The coup was launched at

Benghazi,

and within two hours the takeover was completed. Army units quickly

rallied in support of the coup, and within a few days firmly established

military control in Tripoli and elsewhere throughout the country.

Popular reception of the coup, especially by younger people in the urban

areas, was enthusiastic. Fears of resistance in

Cyrenaica and

Fezzan proved unfounded. No deaths or violent incidents related to the coup were reported.

The Free Officers Movement, which claimed credit for carrying out

the coup, was headed by a twelve-member directorate that designated

itself the Revolutionary Command Council (RCC). This body constituted

the Libyan government after the coup. In its initial proclamation on 1

September, the RCC declared the country to be a free and sovereign state called the Libyan Arab Republic,

which would proceed "in the path of freedom, unity, and social justice,

guaranteeing the right of equality to its citizens, and opening before

them the doors of honorable work." The rule of the Turks and Italians

and the "reactionary" government just overthrown were characterized as

belonging to "dark ages", from which the Libyan people were called to

move forward as "free brothers" to a new age of prosperity, equality,

and honor.

The RCC advised diplomatic representatives in Libya that the

revolutionary changes had not been directed from outside the country,

that existing treaties and agreements would remain in effect, and that

foreign lives and property would be protected. Diplomatic recognition of

the new government came quickly from countries throughout the world.

United States recognition was officially extended on 6 September.

Post-coup

In view of the lack of internal resistance, it appeared that the

chief danger to the new government lay in the possibility of a reaction

inspired by the absent King Idris or his designated heir,

Hasan Al-Rida,

who had been taken into custody at the time of the coup along with

other senior civil and military officials of the royal government.

Within days of the coup, however, Hasan publicly renounced all rights to

the throne, stated his support for the new government, and called on

the people to accept it without violence.

Idris, in an exchange of messages with the RCC through Egypt's President

Nasser,

dissociated himself from reported attempts to secure British

intervention and disclaimed any intention of coming back to Libya. In

return, he was assured by the RCC of the safety of his family still in

the country. At his own request and with Nasser's approval, Idris took

up residence once again in Egypt, where he had spent his first exile and

where he remained until his death in 1983.

On 7 September 1969, the RCC announced that it had appointed a

cabinet to conduct the government of the new republic. An

American-educated technician,

Mahmud Sulayman al-Maghribi,

who had been imprisoned since 1967 for his political activities, was

designated prime minister. He presided over the eight-member Council of

Ministers, of whom six, like Maghrabi, were civilians and two –

Adam Said Hawwaz and

Musa Ahmad – were military officers. Neither of the officers was a member of the RCC.

The Council of Ministers was instructed to "implement the state's

general policy as drawn up by the RCC", leaving no doubt where ultimate

authority rested. The next day the RCC decided to promote Captain

Gaddafi to colonel and to appoint him commander in chief of the Libyan

Armed Forces. Although RCC spokesmen declined until January 1970 to

reveal any other names of RCC members, it was apparent from that date

onward that the head of the RCC and new de facto head of state was Gaddafi.

Analysts were quick to point out the striking similarities

between the Libyan military coup of 1969 and that in Egypt under Nasser

in 1952, and it became clear that the Egyptian experience and the

charismatic figure of Nasser had formed the model for the Free Officers

Movement. As the RCC in the last months of 1969 moved vigorously to

institute domestic reforms, it proclaimed neutrality in the

confrontation between the superpowers and opposition to all forms of

colonialism and "imperialism". It also made clear Libya's dedication to

Arab unity and to the support of the Palestinian cause against Israel.

The RCC reaffirmed the country's identity as part of the "Arab nation" and its state religion as

Islam.

It abolished parliamentary institutions, all legislative functions

being assumed by the RCC, and continued the prohibition against

political parties, in effect since 1952. The new government

categorically rejected communism – in large part because it was

atheist

– and officially espoused an Arab interpretation of socialism that

integrated Islamic principles with social, economic, and political

reform. Libya had shifted, virtually overnight, from the camp of

conservative Arab traditionalist states to that of the radical

nationalist states.

Libyan Arab Republic (1969–1977)

Attempted counter-coups

Following the formation of the Libyan Arab Republic,

Gaddafi and his associates insisted that their government would not

rest on individual leadership, but rather on collegial decision making.

The first major cabinet change occurred soon after the first

challenge to the government. In December 1969, Adam Said Hawwaz, the

minister of defense, and Musa Ahmad, the minister of interior, were

arrested and accused of planning a coup. In the new cabinet formed after

the crisis, Gaddafi, retaining his post as chairman of the RCC, also

became prime minister and defense minister.

Major Abdel Salam Jallud, generally regarded as second only to Gaddafi in the RCC, became deputy prime minister and minister of interior. This cabinet totaled thirteen members, of whom five were RCC officers. The government was challenged a second time in July 1970 when Abdullah Abid Sanusi and

Ahmed al-Senussi,

distant cousins of former King Idris, and members of the Sayf an Nasr

clan of Fezzan were accused of plotting to seize power for themselves.

After the plot was foiled, a substantial cabinet change occurred, RCC

officers for the first time forming a majority among new ministers.

Assertion of Gaddafi's control

From

the start, RCC spokesmen had indicated a serious intent to bring the

"defunct regime" to account. In 1971 and 1972 more than 200 former

government officials—including seven prime ministers and numerous

cabinet ministers—as well as former King Idris and members of the royal

family, were brought to trial on charges of treason and corruption in

the

Libyan People's Court.

Many, who like Idris lived in exile, were

tried in absentia.

Although a large percentage of those charged were acquitted, sentences

of up to fifteen years in prison and heavy fines were imposed on others.

Five death sentences, all but one of them

in absentia, were pronounced, among them, one against Idris.

Fatima, the former queen, and Hasan ar Rida were sentenced to five and three years in prison, respectively.

Meanwhile, Gaddafi and the RCC had disbanded the

Sanusi order

and officially downgraded its historical role in achieving Libya's

independence. He also attacked regional and tribal differences as

obstructions in the path of social advancement and Arab unity,

dismissing traditional leaders and drawing administrative boundaries

across

tribal groupings.

The Free Officers Movement was renamed "

Arab Socialist Union" (ASU) in 1971, modeled after Egypt's

Arab Socialist Union, and made the

sole legal party

in Gaddafi's Libya. It acted as a "vehicle of national expression",

purporting to "raise the political consciousness of Libyans" and to

"aid the RCC in formulating public policy through debate in open

forums".

Trade unions were incorporated into the ASU and strikes outlawed. The

press, already subject to censorship, was officially conscripted in 1972

as an agent of the revolution. Italians and what remained of the Jewish

community were expelled from the country and their property confiscated

in October 1970.

In 1972, Libya joined the

Federation of Arab Republics with

Egypt and

Syria but the intended union of pan-Arabic states never had the intended success, and was effectively dormant after 1973.

As months passed, Gaddafi, caught up in his

apocalyptic visions of revolutionary

Pan-Arabism

and Islam locked in mortal struggle with what he termed the encircling,

demonic forces of reaction, imperialism, and Zionism, increasingly

devoted attention to international rather than internal affairs. As a

result, routine administrative tasks fell to Major Jallud, who in 1972

became prime minister in place of Gaddafi. Two years later Jallud

assumed Gaddafi's remaining administrative and protocol duties to allow

Gaddafi to devote his time to revolutionary theorizing. Gaddafi remained

commander in chief of the armed forces and effective head of state. The

foreign press speculated about an eclipse of his authority and

personality within the RCC, but Gaddafi soon dispelled such theories by

his measures to restructure Libyan society.

Alignment with the Soviet bloc

After the September coup, U.S. forces proceeded deliberately with the planned withdrawal from

Wheelus Air Base

under the agreement made with the previous government. The last of the

American contingent turned the facility over to the Libyans on 11 June

1970, a date thereafter celebrated in Libya as a national holiday.

As relations with the U.S. steadily deteriorated, Gaddafi forged close links with the

Soviet Union and other

Eastern Bloc

countries, all the while maintaining Libya's stance as a nonaligned

country and opposing the spread of communism in the Arab world. Libya's

army—sharply increased from the 6,000-man prerevolutionary force that

had been trained and equipped by the British—was armed with Soviet-built

armor and missiles.

Petroleum politics

The

economic base for Libya's revolution has been its oil revenues.

However, Libya's petroleum reserves were small compared with those of

other major Arab petroleum-producing states. As a consequence, Libya was

more ready to ration output in order to conserve its natural wealth and

less responsive to moderating its price-rise demands than the other

countries. Petroleum was seen both as a means of financing the economic

and social development of a woefully underdeveloped country and as a

political weapon to brandish in the Arab struggle against Israel.

The increase in production that followed the 1969 revolution was

accompanied by Libyan demands for higher petroleum prices, a greater

share of revenues, and more control over the development of the

country's petroleum industry. Foreign petroleum companies agreed to a

price hike of more than three times the going rate (from US$0.90 to

US$3.45 per barrel) early in 1971. In December, the Libyan government

suddenly nationalized the holdings of

British Petroleum

in Libya and withdrew funds amounting to approximately US$550 million

invested in British banks as a result of a foreign policy dispute.

British Petroleum rejected as inadequate a Libyan offer of compensation,

and the British treasury banned Libya from participation in the

sterling area.

In 1973, the Libyan government announced the nationalization of a

controlling interest in all other petroleum companies operating in the

country. This step gave Libya control of about 60 percent of its

domestic oil production by early 1974, a figure that subsequently rose

to 70 percent. Total nationalization was out of the question, given the

need for foreign expertise and funds in oil exploration, production, and

distribution.

1973 oil crisis

Insisting

on the continued use of petroleum as leverage against Israel and its

supporters in the West, Libya strongly urged the Organization of

Petroleum Exporting Countries (

OPEC) to

take action in 1973,

and Libyan militancy was partially responsible for OPEC measures to

raise oil prices, impose embargoes, and gain control of production. On

19 October 1973, Libya was the first Arab nation to issue an oil embargo

against the United States after US President Richard Nixon announced

the US would provide Israel with a $2.2 billion military aid program

during the

Yom Kippur War. Saudi Arabia and other Arab oil producing nations in OPEC would follow suit the next day.

While the other Arab nations lifted their oil embargoes on 18 March 1974, the Gaddafi regime refused to do so.

As a consequence of such policies, Libya's oil production declined by

half between 1970 and 1974, while revenues from oil exports more than

quadrupled. Production continued to fall, bottoming out at an

eleven-year low in 1975 at a time when the government was preparing to

invest large amounts of petroleum revenues in other sectors of the

economy. Thereafter, output stabilized at about two million barrels per

day. Production and hence income declined yet again in the early 1980s

because of the high price of Libyan crude and because recession in the

industrialized world reduced demand for oil from all sources.

Libya's Five-Year Economic and Social Transformation Plan

(1976–80), announced in 1975, was programmed to pump US$20 billion into

the development of a broad range of economic activities that would

continue to provide income after Libya's petroleum reserves had been

exhausted. Agriculture was slated to receive the largest share of aid in

an effort to make Libya self-sufficient in food and to help keep the

rural population on the land. Industry, of which there was little before

the revolution, also received a significant amount of funding in the

first development plan as well as in the second, launched in 1981.

Transition to the Jamahiriya (1973–1977)

(Alfateh, 1 September 1969) Festivity Alfateh in Bayda, Libya, on 1 September 2010.

The "remaking of Libyan society" contained in Gaddafi's ideological

visions began to be put into practice formally in 1973, with a so-called

cultural or popular revolution. This revolution was designed to create

bureaucratic efficiency, public interest and participation in the

subnational governmental system, and national political coordination. In

an attempt to instill revolutionary fervor into his compatriots and to

involve large numbers of them in political affairs, Gaddafi urged them

to challenge traditional authority and to take over and run government

organs themselves. The instrument for doing this was the people's

committee. Within a few months, such committees were found all across

Libya. They were functionally and geographically based, and eventually

became responsible for local and regional administration.

People's committees were established in such widely divergent

organizations as universities, private business firms, government

bureaucracies, and the broadcast media. Geographically based committees

were formed at the governorate, municipal, and zone (lowest) levels.

Seats on the people's committees at the zone level were filled by direct

popular election; members so elected could then be selected for service

at higher levels. By mid-1973 estimates of the number of people's

committees ranged above 2,000. In the scope of their administrative and

regulatory tasks and the method of their members' selection, the

people's committees purportedly embodied the concept of

direct democracy that Gaddafi propounded in the first volume of

The Green Book,

which appeared in 1976. The same concept lay behind proposals to create

a new political structure composed of "people's congresses." The

centerpiece of the new system was the

General People's Congress (GPC), a national representative body intended to replace the RCC.

Libyan–Egyptian War

On July 21, 1977, there were first gun battles between troops on the

border, followed by land and air strikes. Relations between the Libyan

and the Egyptian government had been deteriorating ever since the end of

Yom Kippur War from October 1973, due to Libyan opposition to President

Anwar Sadat's

peace policy as well as the breakdown of unification talks between the

two governments. There is some proof that the Egyptian government was

considering a war against Libya as early as 1974. On February 28, 1974,

during

Henry Kissinger's

visit to Egypt, President Sadat told him about such intentions and

requested that pressure be put on the Israeli government not to launch

an attack on Egypt in the event of its forces being occupied in war with

Libya.

In addition, the Egyptian government had broken its military ties with

Moscow, while the Libyan government kept that cooperation going. The

Egyptian government also gave assistance to former

RCC members Major Abd al Munim al Huni and Omar Muhayshi, who unsuccessfully tried to overthrow

Muammar Gaddafi

in 1975, and allowed them to reside in Egypt. During 1976 relations

were ebbing, as the Egyptian government claimed to have discovered a

Libyan plot to overthrow the government in Cairo. On January 26, 1976,

Egyptian Vice President

Hosni Mubarak indicated in a talk with the US Ambassador

Hermann Eilts

that the Egyptian government intended to exploit internal problems in

Libya to promote actions against Libya, but did not elaborate.

On July 22, 1976, the Libyan government made a public threat to break

diplomatic relations with Cairo if Egyptian subversive actions

continued. On August 8, 1976, an explosion occurred in the bathroom of a government office in

Tahrir Square in Cairo, injuring 14, and the Egyptian government and media claimed this was done by Libyan agents.

The Egyptian government also claimed to have arrested two Egyptian

citizens trained by Libyan intelligence to perform sabotage within

Egypt. On August 23, an Egyptian passenger plane

was hijacked

by persons who reportedly worked with Libyan intelligence. They were

captured by Egyptian authorities in an operation that ended without any

casualties. In retaliation for accusations by the Egyptian government of

Libyan complicity in the hijacking, the Libyan government ordered the

closure of the Egyptian Consulate in Benghazi. On July 24, the combatants agreed to a

ceasefire under the mediation of the

President of Algeria Houari Boumediène and the

Palestine Liberation Organization leader

Yasser Arafat.

Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya (1977–2011)

On 2 March 1977, the General People's Congress (GPC), at Gaddafi's

behest, adopted the "Declaration of the Establishment of the People's

Authority" and proclaimed the

Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya (

Arabic:

الجماهيرية العربية الليبية الشعبية الاشتراكية

al-Jamāhīrīyah al-'Arabīyah al-Lībīyah ash-Sha'bīyah al-Ishtirākīyah).

In the official political philosophy of Gaddafi's state, the

"Jamahiriya" system was unique to the country, although it was presented

as the materialization of the

Third International Theory, proposed by Gaddafi to be applied to the entire

Third World.

The GPC also created the General Secretariat of the GPC, comprising the

remaining members of the defunct Revolutionary Command Council, with

Gaddafi as general secretary, and also appointed the General People's

Committee, which replaced the Council of Ministers, its members now

called secretaries rather than ministers.

Etymology

Jamahiriya (

Arabic:

جماهيرية

jamāhīrīyah) is an

Arabic term generally translated as "state of the masses"; Lisa Anderson

has suggested "peopledom" or "state of the masses" as a reasonable

approximations of the meaning of the term as intended by Gaddafi. The

term does not occur in this sense in

Muammar Gaddafi's

Green Book of 1975. The

nisba-adjective

jamāhīrīyah ("mass-, "of the masses") occurs only in the third part, published in 1981, in the phrase

إن الحركات التاريخية هي الحركات الجماهيرية (

Inna al-ḥarakāt at-tārīkhīyah hiya al-ḥarakāt al-jamāhīrīyah), translated in the English edition as "Historic movements are mass movements".

The word

jamāhīrīyah was derived from

jumhūrīyah, which is the usual Arabic translation of "republic". It was coined by changing the component

jumhūr — "public" — to its plural form,

jamāhīr — "the masses". Thus, it is similar to the term

People's Republic. It is often left untranslated in English, with the long-form name thus rendered as

Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya. However, in

Hebrew, for instance,

jamāhīrīyah is translated as "קהילייה" (

qehiliyáh), a word also used to translate the term "Commonwealth" when referring to the designation of a country.

After weathering the

1986 U.S. bombing by the Reagan administration, Gaddafi added the specifier "Great" (

العظمى al-'Uẓmá) to the official name of the country.

Reforms (1977–1980)

The UNDP's Human Development Index (based on 2010 data, published on 4 November 2010)

|

0.900 and over

0.850–0.899

0.800–0.849

0.750–0.799

0.700–0.749

|

0.650–0.699

0.600–0.649

0.550–0.599

0.500–0.549

0.450–0.499

|

0.400–0.449

0.350–0.399

0.300–0.349

under 0.300

Data unavailable

|

Gaddafi as permanent "Leader of the Revolution"

The

changes in Libyan leadership since 1976 culminated in March 1979, when

the General People's Congress declared that the "vesting of power in the

masses" and the "separation of the state from the revolution" were

complete. The government was divided into two parts, the "Jamahiriya

sector" and the "revolutionary sector". The "Jamahiriya sector" was

composed of the General People's Congress, the General People's

Committee, and the local

Basic People's Congresses. Gaddafi relinquished his position as general secretary of the General People's Congress, as which he was succeeded by

Abdul Ati al-Obeidi, who had been prime minister since 1977.

The "Jamahiriya sector" was overseen by the "revolutionary sector", headed by Gaddafi as "Leader of the Revolution" (Qā'id)

and the surviving members of the Revolutionary Command Council, which

held office owing to their role in the 1969 coup and were therefore not

subject to election. They oversaw the "revolutionary committees", which

were nominally grass-roots organizations that helped keep the people

engaged. As a result, although Gaddafi held no formal government office

after 1979, he retained control of the government and the country. Gaddafi also remained supreme commander of the armed forces.

Administrative reforms

All

legislative and executive authority was vested in the GPC. This body,

however, delegated most of its important authority to its general

secretary and General Secretariat and to the General People's Committee.

Gaddafi, as general secretary of the GPC, remained the primary decision

maker, just as he had been when chairman of the RCC. In turn, all

adults had the right and duty to participate in the deliberation of

their local Basic People's Congress (BPC), whose decisions were passed

up to the GPC for consideration and implementation as national policy.

The BPCs were in theory the repository of ultimate political authority

and decision making, embodying what Gaddafi termed direct "people's

power". The 1977 declaration and its accompanying resolutions amounted

to a fundamental revision of the 1969 constitutional proclamation,

especially with respect to the structure and organization of the

government at both national and subnational levels.

Continuing to revamp Libya's political and administrative

structure, Gaddafi introduced yet another element into the body politic.

Beginning in 1977, "revolutionary committees" were organized and

assigned the task of "absolute revolutionary supervision of people's

power"; that is, they were to guide the people's committees, "raise the

general level of political consciousness and devotion to revolutionary

ideals". In reality, the revolutionary committees were used to survey

the population and repress any political opposition to Gaddafi's

autocratic rule. Reportedly 10% to 20% of Libyans worked in

surveillance for these committees, a proportion of informants on par

with

Ba'athist Iraq or

Juche Korea.

Filled with politically astute zealots, the ubiquitous

revolutionary committees in 1979 assumed control of BPC elections.

Although they were not official government organs, the revolutionary

committees became another mainstay of the domestic political scene. As

with the people's committees and other administrative innovations since

the revolution, the revolutionary committees fit the pattern of imposing

a new element on the existing subnational system of government rather

than eliminating or consolidating already existing structures. By the

late 1970s, the result was an unnecessarily complex system of

overlapping jurisdictions in which cooperation and coordination among

different elements were compromised by ill-defined authority and

responsibility. The ambiguity may have helped serve Gaddafi's aim to

remain the prime mover behind Libyan governance, while minimizing his

visibility at a time when internal opposition to political repression

was rising.

The RCC was formally dissolved and the government was again

reorganized into people's committees. A new General People's Committee

(cabinet) was selected, each of its "secretaries" becoming head of a

specialized people's committee; the exceptions were the "secretariats"

of petroleum, foreign affairs, and heavy industry, where there were no

people's committees. A proposal was also made to establish a "people's

army" by substituting a national militia, being formed in the late

1970s, for the national army. Although the idea surfaced again in early

1982, it did not appear to be close to implementation.

Gaddafi also wanted to combat the strict social restrictions that

had been imposed on women by the previous regime, establishing the

Revolutionary Women's Formation to encourage reform. In 1970, a law was

introduced affirming equality of the sexes and insisting on wage parity.

In 1971, Gaddafi sponsored the creation of a Libyan General Women's

Federation. In 1972, a law was passed criminalizing the marriage of any

females under the age of sixteen and ensuring that a woman's consent was

a necessary prerequisite for a marriage.

Economic reforms

Remaking of the economy was parallel with the attempt to remold

political and social institutions. Until the late 1970s, Libya's

economy was mixed,

with a large role for private enterprise except in the fields of oil

production and distribution, banking, and insurance. But according to

volume two of Gaddafi's Green Book, which appeared in 1978, private

retail trade, rent, and wages were forms of exploitation that should be

abolished. Instead,

workers' self-management committees and profit participation partnerships were to function in public and private enterprises.

A property law was passed that forbade ownership of more than one

private dwelling, and Libyan workers took control of a large number of

companies, turning them into state-run enterprises. Retail and wholesale

trading operations were replaced by state-owned "people's

supermarkets", where Libyans in theory could purchase whatever they

needed at low prices. By 1981 the state had also restricted access to

individual bank accounts to draw upon privately held funds for

government projects. The measures created resentment and opposition

among the newly dispossessed. The latter joined those already alienated,

some of whom had begun to leave the country. By 1982, perhaps 50,000 to

100,000 Libyans had gone abroad; because many of the emigrants were

among the enterprising and better educated Libyans, they represented a

significant loss of managerial and technical expertise.

The government also built a trans-Sahara water pipeline from

major aquifers to both a network of reservoirs and the towns of Tripoli,

Sirte and Benghazi in 2006–2007. It is part of the

Great Manmade River project, started in 1984. It is pumping large resources of water from the

Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System to both urban populations and new irrigation projects around the country.

Libya continued to be plagued with a shortage of skilled labor,

which had to be imported along with a broad range of consumer goods,

both paid for with petroleum income. The country consistently ranked as

the African nation with the highest HDI, standing at 0.755 in 2010,

which was 0.041 higher than the next highest African HDI that same year.

Gender equality was a major achievement under Gaddafi's rule. According

to Lisa Anderson, president of the American University in Cairo and an

expert on Libya, said that under Gaddafi more women attended university

and had "dramatically" more employment opportunities.

Military

Wars against Chad and Egypt

As early as 1969, Gaddafi waged a campaign against

Chad. Scholar Gerard Prunier claims part of his hostility was apparently because

Chadian President François Tombalbaye was Christian.

Libya was also involved in a sometimes violent territorial dispute with neighbouring Chad over the

Aouzou Strip, which Libya occupied in 1973. This dispute eventually led to the

Libyan invasion of Chad. The prolonged foray of Libyan troops into the

Aozou Strip

in northern Chad, was finally repulsed in 1987, when extensive US and

French help to Chadian rebel forces and the government headed by former

Defence Minister

Hissein Habré finally led to a Chadian victory in the so-called

Toyota War. The conflict ended in a ceasefire in 1987. After a judgement of the

International Court of Justice on 13 February 1994, Libya withdrew troops from Chad the same year and the dispute was settled.

Islamic Legion

In 1972, Gaddafi created the

Islamic Legion as a tool to unify and Arabize the region. The priority of the Legion was first Chad, and then Sudan. In

Darfur, a western province of Sudan, Gaddafi supported the creation of the

Arab Gathering

(Tajammu al-Arabi), which according to Gérard Prunier was "a militantly

racist and pan-Arabist organization which stressed the 'Arab' character

of the province." The two organizations shared members and a source of support, and the distinction between them is often ambiguous.

This Islamic Legion was mostly composed of immigrants from poorer

Sahelian countries,

but also, according to a source, thousands of Pakistanis who had been

recruited in 1981 with the false promise of civilian jobs once in Libya.

Generally speaking, the Legion's members were immigrants who had gone

to Libya with no thought of fighting wars, and had been provided with

inadequate military training and had sparse commitment. A French

journalist, speaking of the Legion's forces in Chad, observed that they

were "foreigners, Arabs or Africans,

mercenaries

in spite of themselves, wretches who had come to Libya hoping for a

civilian job, but found themselves signed up more or less by force to go

and fight in an unknown desert."

At the beginning of the 1987 Libyan offensive in Chad, it

maintained a force of 2,000 in Darfur. The nearly continuous

cross-border raids that resulted greatly contributed to a separate

ethnic conflict within Darfur that killed about 9,000 people between

1985 and 1988.

Attempts at nuclear and chemical weapons

In 1972, Gaddafi tried to buy a nuclear bomb from the

People's Republic of China. He then tried to get a bomb from Pakistan, but Pakistan severed its ties before it succeeded in building a bomb. In 1978, Gaddafi turned to Pakistan's rival, India, for help building its own nuclear bomb. In July 1978, Libya and India signed a

memorandum of understanding to cooperate in peaceful applications of nuclear energy as part of India's Atom of Peace policy. In 1991, then

Prime Minister Navaz Sharif paid a

state visit to Libya to hold talks on the promotion of a

Free Trade Agreement between Pakistan and Libya.

However, Gaddafi focused on demanding Pakistan's Prime Minister sell

him a nuclear weapon, which surprised many of the Prime Minister's

delegation members and journalists.

When Prime minister Sharif refused Gaddafi's demand, Gaddafi

disrespected him, calling him a "Corrupt politician", a term which

insulted and surprised Sharif. The Prime minister cancelled the talks, returned to Pakistan and expelled the Libyan Ambassador from Pakistan.

Thailand reported its citizens had helped build storage facilities for nerve gas.

Germany sentenced a businessman, Jurgen Hippenstiel-Imhausen, to five

years in prison for involvement in Libyan chemical weapons. Inspectors from the

Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) verified in 2004 that Libya owned a stockpile of 23 metric tons of

mustard gas and more than 1,300 metric tons of precursor chemicals.

Gulf of Sidra incidents and US air strikes

When Libya was under pressure from international disputes, on 19 August 1981, a naval

dogfight occurred over the

Gulf of Sirte in the

Mediterranean Sea. US

F-14 Tomcat jets fired anti-aircraft missiles against a formation of Libyan fighter jets in this dogfight and shot down two

Libyan Su-22 Fitter

attack aircraft. This naval action was a result of claiming the

territory and losses from the previous incident. A second dogfight

occurred on 4 January 1989; US carrier-based jets also shot down two

Libyan MiG-23 Flogger-Es in the same place.

A similar action occurred on 23 March 1986; while patrolling the

Gulf, US naval forces attacked a sizable naval force and various SAM

sites defending Libyan territory. US fighter jets and fighter-bombers

destroyed SAM launching facilities and sank various naval vessels,

killing 35 seamen. This was a reprisal for terrorist hijackings between

June and December 1985.

On 5 April 1986, Libyan agents

bombed "La Belle" nightclub in West Berlin,

killing three and injuring 229. Gaddafi's plan was intercepted by

several national intelligence agencies and more detailed information was

retrieved four years later from

Stasi archives. The Libyan agents who had carried out the operation, from the Libyan embassy in

East Germany, were prosecuted by the reunited Germany in the 1990s.

In response to the discotheque bombing, joint US Air Force, Navy

and Marine Corps air-strikes took place against Libya on 15 April 1986

and code-named Operation El Dorado Canyon and known as the

1986 bombing of Libya. Air defenses, three army bases, and two airfields in

Tripoli and

Benghazi

were bombed. The surgical strikes failed to kill Gaddafi but he lost a

few dozen military officers. Gaddafi spread propaganda how it had killed

his "adopted daughter" and how victims had been all "civilians".

Despite the variations of the stories, the campaign was successful, and a

large proportion of the Western press reported the government's stories

as facts.

Following the 1986 bombing of Libya, Gaddafi intensified his support for anti-American government organizations. He financed

Jeff Fort's

Al-Rukn faction of the Chicago

Black P. Stones gang, in their emergence as an indigenous anti-American armed revolutionary movement.

Al-Rukn members were arrested in 1986 for preparing strikes on behalf

of Libya, including blowing up US government buildings and bringing down

an airplane; the Al-Rukn defendants were convicted in 1987 of "offering

to commit bombings and assassinations on US soil for Libyan payment."

In 1986, Libyan state television announced that Libya was training

suicide squads to attack American and European interests. He began

financing the IRA again in 1986, to retaliate against the British for

harboring American fighter planes.

Gaddafi announced that he had won a spectacular military victory

over the US and the country was officially renamed the "Great Socialist

People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriyah".

However, his speech appeared devoid of passion and even the "victory"

celebrations appeared unusual. Criticism of Gaddafi by ordinary Libyan

citizens became more bold, such as defacing of Gaddafi posters. The raids against Libyan military had brought the government to its weakest point in 17 years.

International relations

Africa

Gaddafi was a close supporter of Ugandan President

Idi Amin.

Gaddafi sent thousands of troops to fight against Tanzania on

behalf of Idi Amin. About 600 Libyan soldiers lost their lives

attempting to defend the collapsing presidency of Amin. Amin was

eventually exiled from Uganda to Libya before settling in Saudi Arabia.

Gaddafi also aided

Jean-Bédel Bokassa, the Emperor of the

Central African Empire. He also intervened militarily in the renewed Central African Republic in 2001 to protect his ally

Ange-Félix Patassé.

Patassé signed a deal giving Libya a 99-year lease to exploit all of

that country's natural resources, including uranium, copper, diamonds,

and oil.

Gaddafi was a strong opponent of

apartheid in

South Africa and forged a friendship with

Nelson Mandela. One of Mandala's grandsons is named Gaddafi, an indication of the latter's support in South Africa. Gaddafi funded Mandela's

1994 election campaign,

and after taking office as the country's first democratically-elected

president in 1994, Mandela rejected entreaties from U.S. President

Bill Clinton and others to cut ties with Gaddafi. Mandela later played a key role in helping Gaddafi gain mainstream acceptance in the Western world later in the 1990s. Over the years, Gaddafi came to be seen as a hero in much of Africa due to his revolutionary image.

Gaddafi's World Revolutionary Center (WRC) near Benghazi became a training center for groups backed by Gaddafi. Graduates in power as of 2011 include

Blaise Compaoré of Burkina Faso and

Idriss Déby of Chad.

Gaddafi's strong military support and finances gained him allies across the continent. He had himself crowned with the title "

King of Kings of Africa"

in 2008, in the presence of over 200 African traditional rulers and

kings, although his views on African political and military unification

received a lukewarm response from their governments.

His 2009 forum for African kings was canceled by the Ugandan hosts, who

believed that traditional rulers discussing politics would lead to

instability. On 1 February 2009, a '

coronation ceremony' in

Addis Ababa,

Ethiopia, was held to coincide with the 53rd African Union Summit, at

which he was elected head of the African Union for the year. Gaddafi told the assembled African leaders: "I shall continue to insist that our sovereign countries work to achieve the

United States of Africa."

In 1986, 2000, and the months prior to the 2011 civil war, Gaddafi announced plans for a unified African

gold dinar

currency, to challenge the dominance of the US Dollar and Euro

currencies. The African dinar would have been measured directly in terms

of gold.

Gaddafi and international terrorism

In 1971 Gaddafi warned that if France opposes Libyan military

occupation of Chad, he will use all weapons in the war against France

including the "revolutionary weapon".

On 11 June 1972, Gaddafi announced that any Arab wishing to volunteer

for Palestinian terrorist groups "can register his name at any Libyan

embassy will be given adequate training for combat". He also promised

financial support for attacks. On 7 October 1972, Gaddafi praised the

Lod Airport massacre, executed by the communist

Japanese Red Army, and demanded Palestinian terrorist groups to carry out similar attacks.

Reportedly, Gaddafi was a major financier of the "

Black September Movement" which perpetrated the

Munich massacre at the

1972 Summer Olympics. In 1973 the

Irish Naval Service intercepted the vessel

Claudia in Irish territorial waters, which carried Soviet arms from Libya to the Provisional IRA. In 1976 after a series of terror activities by the

Provisional IRA,

Gaddafi announced that "the bombs which are convulsing Britain and

breaking its spirit are the bombs of Libyan people. We have sent them to

the Irish revolutionaries so that the British will pay the price for

their past deeds".

Gaddafi also became a strong supporter of the

Palestine Liberation Organization,

which support ultimately harmed Libya's relations with Egypt, when in

1979 Egypt pursued a peace agreement with Israel. As Libya's relations

with Egypt worsened, Gaddafi sought closer relations with the Soviet

Union. Libya became the first country outside the Soviet bloc to receive

the supersonic

MiG-25

combat fighters, but Soviet-Libyan relations remained relatively

distant. Gaddafi also sought to increase Libyan influence, especially in

states with an

Islamic population, by calling for the creation of a Saharan Islamic state and supporting anti-government forces in

sub-Saharan Africa.

In the 1970s and the 1980s, this support was sometimes so freely

given that even the most unsympathetic groups could obtain Libyan

support; often the groups represented ideologies far removed from

Gaddafi's own. Gaddafi's approach often tended to confuse international

opinion.

In October 1981 Egypt's President

Anwar Sadat was assassinated. Gaddafi applauded the murder and remarked that it was a "punishment".

In December 1981, the

US State Department invalidated US passports for travel to Libya, and in March 1982, the U.S. declared a ban on the import of Libyan

oil.

Gaddafi reportedly spent hundreds of millions of the government's money on training and arming Sandinistas in Nicaragua.

Daniel Ortega, the President of Nicaragua, was his ally.

In April 1984, Libyan refugees in London protested against

execution of two dissidents. Communications intercepted by MI5 show that

Tripoli ordered its diplomats to direct violence against the

demonstrators. Libyan diplomats shot at 11 people and killed British

policewoman

Yvonne Fletcher. The incident led to the breaking off of

diplomatic relations between the United Kingdom and Libya for over a decade.

After December 1985

Rome and Vienna airport attacks, which killed 19 and wounded around 140, Gaddafi indicated that he would continue to support the

Red Army Faction, the

Red Brigades, and the Irish Republican Army as long as European countries support anti-Gaddafi Libyans.

The Foreign Minister of Libya also called the massacres "heroic acts".

In 1986, Libyan state television announced that Libya was training suicide squads to attack American and European interests.

On 5 April 1986, Libyan agents were alleged with

bombing the "La Belle" nightclub in West Berlin,

killing three people and injuring 229 people who were spending evening

there. Gaddafi's plan was intercepted by Western intelligence.

More-detailed information was retrieved years later when

Stasi

archives were investigated by the reunited Germany. Libyan agents who

had carried out the operation from the Libyan embassy in East Germany

were prosecuted by reunited Germany in the 1990s.

In May 1987, Australia broke off relations with Libya because of its role in fueling violence in Oceania.

Under Gaddafi, Libya had a long history of supporting the

Irish Republican Army. In late 1987 French authorities stopped a merchant vessel, the

MV Eksund, which was delivering a 150-ton Libyan arms shipment to the IRA.

In Britain, Gaddafi's best-known political subsidiary is the

Workers Revolutionary Party.

In New Zealand, Libya attempted to radicalize

Māoris.

In Australia, there were several cases of attempted

radicalisation of Australian Aborigines, with individuals receiving

paramilitary training in Libya. Libya put several left-wing unions on

the Libyan payroll, such as the Food Preservers Union (FPU) and the

Federated Confectioners Association of Australia (FCA). Labour Party politician

Bill Hartley, the secretary of Libya-Australia friendship society, was long-term supporter of Gaddafi and Saddam Hussein.

In the 1980s, the Libyan government purchased advertisements in

Arabic-language newspapers in Australia asking for Australian Arabs to

join the military units of his worldwide struggle against imperialism.

In part, because of this, Australia banned recruitment of foreign

mercenaries in Australia.

Some publications were financed by Gaddafi. The Socialist Labour League's Workers News

was one such publication: "in among the routine denunciations of

uranium mining and calls for greater trade union militancy would be a

couple of pages extolling Gaddafi's fatuous and incoherent green book

and the Libyan revolution."

International sanctions after the Lockerbie bombing (1992–2003)

Libya was accused in the 1988 bombing of

Pan Am Flight 103 over

Lockerbie,

Scotland; UN sanctions were imposed in 1992.

UN Security Council

resolutions (UNSCRs) passed in 1992 and 1993 obliged Libya to fulfill

requirements related to the Pan Am 103 bombing before sanctions could be

lifted, leading to Libya's political and economic isolation for most of

the 1990s. The UN sanctions cut airline connections with the outer

world, reduced diplomatic representation and prohibited the sale of

military equipment. Oil-related sanctions were assessed by some as

equally significant for their exceptions: thus sanctions froze Libya's

foreign assets (but excluded revenue from oil and natural gas and

agricultural commodities) and banned the sale to Libya of refinery or

pipeline equipment (but excluded oil

production equipment).

Under the sanctions Libya's refining capacity eroded. Libya's

role on the international stage grew less provocative after UN sanctions

were imposed. In 1999, Libya fulfilled one of the UNSCR requirements by

surrendering two Libyans suspected in connection with the bombing for

trial before a Scottish court in the Netherlands. One of these suspects,

Abdel Basset al-Megrahi, was found guilty; the other was acquitted. UN

sanctions against Libya were subsequently suspended. The full lifting of

the sanctions, contingent on Libya's compliance with the remaining

UNSCRs, including acceptance of responsibility for the actions of its

officials and payment of appropriate compensation, was passed 12

September 2003, explicitly linked to the release of up to $2.7 billion

in Libyan funds to the families of the 1988 attack's 270 victims.

In 2002, Gaddafi paid a ransom reportedly worth tens of millions of dollars to

Abu Sayyaf,

a Filipino Islamist militancy, to release a number of kidnapped

tourists. He presented it as an act of goodwill to Western countries;

nevertheless the money helped the group to expand its operation.

Normalization of international relations (2003–2010)

In

December 2003, Libya announced that it had agreed to reveal and end its

programs to develop weapons of mass destruction and to renounce

terrorism, and Gaddafi made significant strides in normalizing relations

with western nations. He received various Western European leaders as

well as many working-level and commercial delegations, and made his

first trip to Western Europe in 15 years when he traveled to

Brussels

in April 2004. Libya responded in good faith to legal cases brought

against it in U.S. courts for terrorist acts that predate its

renunciation of violence. Claims for compensation in the Lockerbie

bombing, LaBelle disco bombing, and UTA 772 bombing cases are ongoing.

The U.S. rescinded Libya's designation as a

state sponsor of terrorism

in June 2006. In late 2007, Libya was elected by the General Assembly

to a nonpermanent seat on the United Nations Security Council for the

2008–2009 term. Currently,

Operation Enduring Freedom - Trans Sahara is being fought in Libya's portion of the

Sahara Desert.

Purification laws

In 1994, the

General People's Congress

approved the introduction of "purification laws" to be put into effect,

punishing theft by the amputation of limbs, and fornication and

adultery by flogging. Under the Libyan constitution, homosexual relations are punishable by up to five years in jail.

Opposition, coups and revolts

Throughout his long rule, Gaddafi had to defend his position against

opposition and coup attempts, emerging both from the military and from

the general population. He reacted to these threats on one hand by

maintaining a careful balance of power between the forces in the

country, and by brutal repression on the other. Gaddafi successfully

balanced the various

tribes of Libya one against the other by distributing his favours. To forestall a military coup, he deliberately weakened the

Libyan Armed Forces by regularly rotating officers, relying instead on loyal elite troops such as his

Revolutionary Guard Corps, the special-forces

Khamis Brigade and his personal

Amazonian Guard,

even though emphasis on political loyalty tended, over the long run, to

weaken the professionalism of his personal forces. This trend made the

country vulnerable to dissension at a time of crisis, as happened during

early 2011.

Political repression and "Green Terror"

The term "Green Terror" is used to describe campaigns of violence and

intimidation against opponents of Gaddafi, particularly in reference to

wave of oppression during Libya's

cultural revolution, or to the wave of highly publicized hangings of regime opponents that began with the

Execution of Al-Sadek Hamed Al-Shuwehdy. Dissent was illegal under Law 75 of 1973. Reportedly 10 to 20 percent of Libyans worked in surveillance for Gaddafi's Revolutionary Committees, a proportion of informants on par with

Saddam Hussein's Iraq or

Kim Jong Il's North Korea. The surveillance took place in government, in factories, and in the education sector.

Following an abortive attempt to replace English foreign language education with Russian,

in recent years English has been taught in Libyan schools from a

primary level, and students have access to English-language media.

However, one protester in 2011 described the situation as: "None of us

can speak English or French. He kept us ignorant and blindfolded".

According to the 2009

Freedom of the Press Index, Libya is the most censored country in the Middle East and North Africa.

Prisons are run with little or no documentation of the inmate

population or of such basic data as prisoner's crime and sentence.

Opposition to the Jamahiriya reforms

During the late 1970s, some exiled Libyans

formed active opposition groups. In early 1979, Gaddafi warned

opposition leaders to return home immediately or face "liquidation."

When caught, they could face being sentenced and hanged in public.

It is the Libyan people's responsibility to liquidate such scums who are distorting Libya's image abroad.

— Gaddafi talking about exiles in 1982.

Gaddafi employed his network of diplomats and recruits to assassinate dozens of his critics around the world.

Amnesty International listed at least twenty-five assassinations between 1980 and 1987.

Gaddafi's agents were active in the U.K., where many Libyans had

sought asylum. After Libyan diplomats shot at 15 anti-Gaddafi protesters

from inside the Libyan embassy's first floor and killed

a British policewoman, the U.K. broke off relations with Gaddafi's government as a result of the incident.

Even the U.S. could not protect dissidents from Libya. In 1980, a Libyan agent attempted to assassinate dissident

Faisal Zagallai, a doctoral student at the

University of Colorado at Boulder. The bullets left Zagallai partially blinded. A defector was kidnapped and executed in 1990 just before he was about to receive U.S. citizenship.

Gaddafi asserted in June 1984 that killings could be carried out

even when the dissidents were on pilgrimage in the holy city of

Mecca. In August 1984, one Libyan plot was thwarted in Mecca.

[57]

As of 2004, Libya still provided bounties for heads of critics, including 1 million dollars for

Ashur Shamis, a Libyan-British journalist.

There is indication that between the years of 2002 and 2007, Libya's Gaddafi-era

intelligence service had a partnership with western spy organizations including

MI6 and the

CIA,

who voluntarily provided information on Libyan dissidents in the United

States and Canada in exchange for using Libya as a base for

extraordinary renditions.

This was done despite Libya's history of murdering dissidents abroad,

and with full knowledge of Libya's brutal mistreatment of detainees.

Political unrest during the 1990s

In the 1990s, Gaddafi's rule was threatened by militant

Islamism.

In October 1993, there was an unsuccessful assassination attempt on

Gaddafi by elements of the Libyan army. In response, Gaddafi used

repressive measures, using his personal

Revolutionary Guard Corps to crush riots and Islamist activism during the 1990s. Nevertheless,

Cyrenaica between 1995 and 1998 was politically unstable, due to the tribal allegiances of the local troops.

2011 civil war and collapse of Gaddafi's government

A global map of the world showing countries that recognised or had informal relations with the Libyan Republic during the civil war of 2011.

Libya

Countries

that had permanent informal relations with the NTC, or which voted in

favor of recognition at the UN, but had not granted official recognition

Countries which opposed recognition of the NTC at the UN, but had not made a formal statement

Countries that said they would not recognise the NTC

A renewed serious threat to the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya came in February 2011, with the

Libyan Civil War. The novelist Idris Al-Mesmari was arrested hours after giving an interview with

Al Jazeera about the police reaction to protests in Benghazi on 15 February.

Inspiration for the unrest is attributed to the uprisings in

Tunisia and

Egypt, connecting it with the wider

Arab Spring. On 22 February,

The Economist described the events as an "uprising that is trying to reclaim Libya from the world's longest-ruling

autocrat."

Gaddafi had referred to the opposition variously as "rats",

"cockroaches", and "drugged kids" and accused them of being part of

al-Qaeda. In the east, the

National Transitional Council was established in Benghazi.

Gaddafi's son,

Khamis, controlled the well-armed

Khamis Brigade and alleged to possess large number of mercenaries.

Some Libyan officials

had sided with the protesters and requested help from the international

community to bring an end to the massacres of civilians. The government

in

Tripoli had lost control of half of Libya by the end of February, but as of mid-September Gaddafi remained in control of several parts of

Fezzan.

On 21 September, the forces of NTC captured Sabha, the largest city of

Fezzan, reducing the control of Gaddafi to limited and isolated areas.

The UN resolution authorised air-strikes against Libyan ground troops and warships that appeared to threaten civilians. On 19 March, the no-fly zone enforcement began, with French aircraft undertaking sorties across Libya and a naval

blockade by the British

Royal Navy. Eventually, the aircraft carriers

USS Enterprise and

Charles de Gaulle

arrived off the coast and provided the enforcers with a rapid-response

capability. U.S. forces named their part of the enforcement action

Operation Odyssey Dawn, meant to "deny the Libyan regime from using force against its own people". said U.S.

Vice Admiral William E. Gortney. More than 110

"Tomahawk" cruise missiles were fired in an initial assault by U.S. warships and a British submarine against Libyan air defences.

The last government holdouts in

Sirte finally fell to anti-Gaddafi fighters on 20 October 2011, and, following the controversial

death of Muammar Gaddafi, Libya was officially declared "liberated" on 23 October 2011, ending 42 years of Gaddafi's leadership in Libya.

Political scientist

Riadh Sidaoui

suggested in October 2011 that Gaddafi "has created a great void for

his exercise of power: there is no institution, no army, no electoral

tradition in the country", and as a result, the period of transition

would be difficult in Libya.