From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

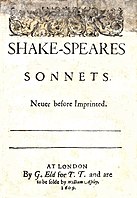

Social forestry in Andhra Pradesh,

India, providing fuel, soil protection, shade, and even well-being to travelers.

Ecosystem services are the many and varied benefits to humans provided by the natural environment and healthy ecosystems. Such ecosystems include, for example, agroecosystems, forest ecosystem, grassland ecosystems, and aquatic ecosystems.

These ecosystems, functioning in healthy relationships, offer such

things as natural pollination of crops, clean air, extreme weather

mitigation, and human mental and physical well-being. Collectively,

these benefits are becoming known as ecosystem services, and are often

integral to the provision of food, the provisioning of clean drinking water, the decomposition of wastes, and the resilience and productivity of food ecosystems.

While scientists and environmentalists have discussed ecosystem services implicitly for decades, the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA) in the early 2000s popularized this concept. There, ecosystem services are grouped into four broad categories: provisioning, such as the production of food and water; regulating, such as the control of climate and disease; supporting, such as nutrient cycles and oxygen production; and cultural, such as spiritual and recreational benefits. To help inform decision-makers, many ecosystem services are being evaluated to draw equivalent comparisons to human-engineered infrastructure and services.

Estuarine and coastal ecosystems are both marine ecosystems.

Together, these ecosystems perform the four categories of ecosystem

services in a variety of ways: "Regulating services" include climate

regulation as well as waste treatment and disease regulation and buffer zones. The "provisioning services" include forest products such as timbers, marine products, fresh water, raw materials, and biochemical and genetic resources. "Cultural services" of coastal ecosystems include inspirational aspects, recreation and tourism, science and education. "Supporting services" of coastal ecosystems include nutrient cycling, biologically mediated habitats, and primary production.

Definition

Ecosystem services or eco-services are defined as the goods and services provided by ecosystems to humans. Per the 2006 Millennium Ecosystem Assessment

(MA), ecosystem services are "the benefits people obtain from

ecosystems". The MA also delineated the four categories of ecosystem

services—supporting, provisioning, regulating, and cultural—discussed

below. In simple terms provision of food materials, water, timber,

fibers, and the provision of medications.

By 2010, there had evolved various working definitions and descriptions of ecosystem services in the literature. To prevent double-counting in ecosystem services audits, for instance, The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity

(TEEB) replaced "Supporting Services" in the MA with "Habitat Services"

and "ecosystem functions", defined as "a subset of the interactions

between ecosystem structure and processes that underpin the capacity of

an ecosystem to provide goods and services".

Categories

Detritivores like this

dung beetle help to turn animal wastes into organic material that can be reused by primary producers.

Four different types of ecosystem services have been distinguished by

the scientific body: regulating services, provisioning services,

cultural services and supporting services. An ecosystem does not

necessarily offer all four types of services simultaneously; but given

the intricate nature of any ecosystem, it is usually assumed that humans

benefit from a combination of these services. The services offered by

diverse types of ecosystems (forests, seas, coral reefs, mangroves,

etc.) differ in nature and in consequence. In fact, some services

directly affect the livelihood of neighboring human populations (such as

fresh water, food or aesthetic value, etc.) while other services affect

general environmental conditions by which humans are indirectly

impacted (such as climate change, erosion regulation or natural hazard regulation, etc.).

The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment report 2005 defined ecosystem

services as benefits people obtain from ecosystems and distinguishes

four categories of ecosystem services, where the so-called supporting

services are regarded as the basis for the services of the other three

categories.

Regulating services

Provisioning services

The following services are also known as ecosystem goods:

- food (including seafood and game), crops, wild foods, and spices

- raw materials (including lumber, skins, fuelwood, organic matter, fodder, and fertilizer)

- genetic resources (including crop improvement genes, and health care)

- biogenic minerals

- medicinal resources (including pharmaceuticals, chemical models, and test and assay organisms)

- energy (hydropower, biomass fuels)

- ornamental resources (including fashion, handicrafts, jewelry, pets,

worship, decoration, and souvenirs like furs, feathers, ivory, orchids,

butterflies, aquarium fish, shells, etc.)

Cultural services

- cultural (including use of nature as motif in books, film, painting, folklore, national symbols, advertising, etc.)

- spiritual and historical (including use of nature for religious or heritage value or natural)

- recreational experiences (including ecotourism, outdoor sports, and recreation)

- science and education (including use of natural systems for school excursions, and scientific discovery)

- therapeutic (including eco-therapy, social forestry and animal assisted therapy)

As of 2012, there was a discussion as to how the concept of cultural

ecosystem services could be operationalized, how landscape aesthetics,

cultural heritage, outdoor recreation, and spiritual significance to

define can fit into the ecosystem services approach.

who vote for models that explicitly link ecological structures and

functions with cultural values and benefits. Likewise, there has been a

fundamental critique of the concept of cultural ecosystem services that

builds on three arguments:

- Pivotal cultural values attaching to the natural/cultivated

environment rely on an area's unique character that cannot be addressed

by methods that use universal scientific parameters to determine

ecological structures and functions.

- If a natural/cultivated environment has symbolic meanings and

cultural values the object of these values are not ecosystems but shaped

phenomena like mountains, lakes, forests, and, mainly, symbolic

landscapes.

- Cultural values do result not from properties produced by ecosystems

but are the product of a specific way of seeing within the given

cultural framework of symbolic experience.

The Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services (CICES)

is a classification scheme developed to accounting systems (like

National counts etc.), in order to avoid double-counting of Supporting

Services with others Provisioning and Regulating Services.

Supporting services

These may be redundant with regulating services in some categorisations, but include services such as, but not limited to, nutrient cycling, primary production, soil formation, habitat

provision. These services make it possible for the ecosystems to

continue providing services such as food supply, flood regulation, and

water purification. Slade et al. outline the situation where a greater number of species would maximize more ecosystem services

Ecology

Understanding of ecosystem services requires a strong foundation in ecology, which describes the underlying principles and interactions of organisms and the environment. Since the scales at which these entities interact can vary from microbes to landscapes,

milliseconds to millions of years, one of the greatest remaining

challenges is the descriptive characterization of energy and material

flow between them. For example, the area of a forest floor, the detritus upon it, the micro organisms in the soil, the soil biodiversity,

and characteristics of the soil itself will all contribute to the

abilities of that forest for providing ecosystem services like carbon

sequestration, water purification, and erosion

prevention to other areas within the watershed. Note that it is often

possible for multiple services to be bundled together and when benefits

of targeted objectives are secured, there may also be ancillary

benefits—the same forest may provide habitat for other organisms as well as human recreation, which are also ecosystem services.

The complexity of Earth's ecosystems poses a challenge for

scientists as they try to understand how relationships are interwoven

among organisms, processes and their surroundings. As it relates to

human ecology, a suggested research agenda for the study of ecosystem services includes the following steps:

- identification of ecosystem service providers (ESPs)—species or populations that provide specific ecosystem services—and characterization of their functional roles and relationships;

- determination of community structure aspects that influence how ESPs function in their natural landscape, such as compensatory responses that stabilize function and non-random extinction sequences which can erode it;

- assessment of key environmental (abiotic) factors influencing the provision of services;

- measurement of the spatial and temporal scales ESPs and their services operate on.

Recently, a technique has been developed to improve and standardize

the evaluation of ESP functionality by quantifying the relative

importance of different species in terms of their efficiency and

abundance.

Such parameters provide indications of how species respond to changes

in the environment (i.e. predators, resource availability, climate) and

are useful for identifying species that are disproportionately important

at providing ecosystem services. However, a critical drawback is that

the technique does not account for the effects of interactions, which

are often both complex and fundamental in maintaining an ecosystem and

can involve species that are not readily detected as a priority. Even

so, estimating the functional structure of an ecosystem and combining it

with information about individual species traits can help us understand

the resilience of an ecosystem amidst environmental change.

Many ecologists also believe that the provision of ecosystem services can be stabilized with biodiversity.

Increasing biodiversity also benefits the variety of ecosystem services

available to society. Understanding the relationship between

biodiversity and an ecosystem's stability is essential to the management

of natural resources and their services.

Redundancy hypothesis

The concept of ecological redundancy is sometimes referred to as functional compensation and assumes that more than one species performs a given role within an ecosystem.

More specifically, it is characterized by a particular species

increasing its efficiency at providing a service when conditions are

stressed in order to maintain aggregate stability in the ecosystem.

However, such increased dependence on a compensating species places

additional stress on the ecosystem and often enhances its susceptibility

to subsequent disturbance. The redundancy hypothesis can be summarized as "species redundancy enhances ecosystem resilience".

Another idea uses the analogy of rivets in an airplane wing to

compare the exponential effect the loss of each species will have on the

function of an ecosystem; this is sometimes referred to as rivet popping.

If only one species disappears, the loss of the ecosystem's efficiency

as a whole is relatively small; however, if several species are lost,

the system essentially collapses—similar to an airplane that has lost

too many rivets. The hypothesis assumes that species are relatively

specialized in their roles and that their ability to compensate for one

another is less than in the redundancy hypothesis. As a result, the loss

of any species is critical to the performance of the ecosystem. The key

difference is the rate at which the loss of species affects total

ecosystem functioning.

Portfolio effect

A third explanation, known as the portfolio effect,

compares biodiversity to stock holdings, where diversification

minimizes the volatility of the investment, or in this case, the risk of

instability of ecosystem services. This is related to the idea of response diversity

where a suite of species will exhibit differential responses to a given

environmental perturbation. When considered together, they create a

stabilizing function that preserves the integrity of a service.

Several experiments have tested these hypotheses in both the field and the lab. In ECOTRON, a laboratory in the UK where many of the biotic and abiotic factors of nature can be simulated, studies have focused on the effects of earthworms and symbiotic bacteria on plant roots.

These laboratory experiments seem to favor the rivet hypothesis.

However, a study on grasslands at Cedar Creek Reserve in Minnesota

supports the redundancy hypothesis, as have many other field studies. See also: Biodiversity#Ecosystem services.

Estuarine and coastal ecosystem services

Estuarine and marine coastal ecosystems are both marine ecosystems.

Together, these ecosystems perform the four categories of ecosystem

services in a variety of ways: "Regulating services" include climate

regulation as well as waste treatment and disease regulation and buffer zones. The "provisioning services" include forest products, marine products, fresh water, raw materials, biochemical and genetic resources. "Cultural services" of coastal ecosystems include inspirational aspects, recreation and tourism, science and education. "Supporting services" of coastal ecosystems include nutrient cycling, biologically mediated habitats and primary production.

Coasts and their adjacent areas on and offshore are an important part of a local ecosystem. The mixture of fresh water and salt water (brackish water) in estuaries provides many nutrients for marine life. Salt marshes, mangroves and beaches also support a diversity of plants, animals and insects crucial to the food chain. The high level of biodiversity

creates a high level of biological activity, which has attracted human

activity for thousands of years. Coasts also create essential material

for organisms to live by, including estuaries, wetland, seagrass, coral reefs, and mangroves. Coasts provide habitats for migratory birds, sea turtles, marine mammals, and coral reefs.

Regulating services

Regulating services are the "benefits obtained from the regulation of ecosystem processes".

In the case of coastal and estuarine ecosystems, these services include

climate regulation, waste treatment and disease control and natural

hazard regulation.

Climate regulation

Both

the biotic and abiotic ensembles of marine ecosystems play a role in

climate regulation. They act as sponges when it comes to gases in the

atmosphere, retaining large levels of CO2 and other greenhouse gases (methane and nitrous oxide). Marine plants also use CO2 for photosynthesis purposes and help in reducing the atmospheric CO2.

The oceans and seas absorb the heat from the atmosphere and

redistribute it through the means of water currents, and atmospheric

processes, such as evaporation and the reflection of light allow for the

cooling and warming of the overlying atmosphere. The ocean temperatures

are thus imperative to the regulation of the atmospheric temperatures

in any part of the world: "without the ocean, the Earth would be

unbearably hot during the daylight hours and frigidly cold, if not

frozen, at night".

Waste treatment and disease regulation

Another

service offered by marine ecosystem is the treatment of wastes, thus

helping in the regulation of diseases. Wastes can be diluted and

detoxified through transport across marine ecosystems; pollutants are

removed from the environment and stored, buried or recycled in marine

ecosystems: "Marine ecosystems break down organic waste through

microbial communities that filter water, reduce/limit the effects of

eutrophication, and break down toxic hydrocarbons into their basic

components such as carbon dioxide, nitrogen, phosphorus, and water".

The fact that waste is diluted with large volumes of water and moves

with water currents leads to the regulation of diseases and the

reduction of toxics in seafood.

Buffer zones

Coastal and estuarine ecosystems act as buffer zones against natural

hazards and environmental disturbances, such as floods, cyclones, tidal

surges and storms. The role they play is to "[absorb] a portion of the

impact and thus [lessen] its effect on the land". Wetlands (which include saltwater swamps, salt marshes,

...) and the vegetation it supports – trees, root mats, etc. – retain

large amounts of water (surface water, snowmelt, rain, groundwater) and

then slowly releases them back, decreasing the likeliness of floods. Mangrove

forests protect coastal shorelines from tidal erosion or erosion by

currents; a process that was studied after the 1999 cyclone that hit

India. Villages that were surrounded with mangrove forests encountered

less damages than other villages that weren't protected by mangroves.

Provisioning services

Provisioning services consist of all "the products obtained from ecosystems".

Forest products

Forests

produce a large type and variety of timber products, including

roundwood, sawnwood, panels, and engineered wood, e.g., cross-laminated

timber, as well as pulp and paper.

Besides the production of timber, forestry activities may also result

in products that undergo little processing, such as fire wood, charcoal,

wood chips and roundwood used in an unprocessed form. Global production and trade of all major wood-based products recorded their highest ever values in 2018. Production, imports and exports of roundwood, sawnwood, wood-based panels, wood pulp, wood charcoal and pellets reached their maximum quantities since 1947 when FAO started reporting global forest product statistics.

In 2018, growth in production of the main wood-based product groups

ranged from 1 percent (woodbased panels) to 5 percent (industrial

roundwood).

The fastest growth occurred in the Asia-Pacific, Northern American and

European regions, likely due to positive economic growth in these areas.

Forests also provide non-wood forest products, including fodder,

aromatic and medicinal plants, and wild foods.Worldwide, around 1

billion people depend to some extent on wild foods such as wild meat,

edible insects, edible plant products, mushrooms and fish, which often

contain high levels of key micronutrients.

The value of forest foods as a nutritional resource is not limited to

low- and middle-income countries; more than 100 million people in the

European Union (EU) regularly consume wild food. Some 2.4 billion people – in both urban and rural settings – use wood-based energy for cooking.

Marine products

Marine

ecosystems provide people with: wild & cultured seafood, fresh

water, fiber & fuel and biochemical & genetic resources.

Humans consume a large number of products originating from the

seas, whether as a nutritious product or for use in other sectors: "More

than one billion people worldwide, or one-sixth of the global

population, rely on fish as their main source of animal protein. In

2000, marine and coastal fisheries accounted for 12 per cent of world

food production".

Fish and other edible marine products – primarily fish, shellfish, roe

and seaweeds – constitute for populations living along the coast the

main elements of the local cultural diets, norms and traditions. A very

pertinent example would be sushi, the national food of Japan, which

consists mostly of different types of fish and seaweed.

Fresh water

Water

bodies that are not highly concentrated in salts are referred to as

'fresh water' bodies. Fresh water may run through lakes, rivers and

streams, to name a few; but it is most prominently found in the frozen

state or as soil moisture or buried deep underground. Fresh water is not

only important for the survival of humans, but also for the survival of

all the existing species of animals, plants.

Raw materials

Marine

creatures provide us with the raw materials needed for the

manufacturing of clothing, building materials (lime extracted from coral

reefs), ornamental items and personal-use items (luffas, art and

jewelry): "The skin of marine mammals for clothing, gas deposits for

energy production, lime (extracted from coral reefs) for building

construction, and the timber of mangroves and coastal forests for

shelter are some of the more familiar uses of marine organisms. Raw

marine materials are utilized for non-essential goods as well, such as

shells and corals in ornamental items".

Humans have also referred to processes within marine environments for

the production of renewable energy: using the power of waves – or tidal

power – as a source of energy for the powering of a turbine, for

example. Oceans and seas are used as sites for offshore oil and gas installations, offshore wind farms.

Biochemical and genetic resources

Biochemical

resources are compounds extracted from marine organisms for use in

medicines, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and other biochemical products.

Genetic resources are the genetic information found in marine organisms

that would later on be used for animal and plant breeding and for

technological advances in the biological field. These resources are

either directly taken out from an organism – such as fish oil as a

source of omega3 –, or used as a model for innovative man-made products:

"such as the construction of fiber optics technology based on the

properties of sponges. ... Compared to terrestrial products,

marine-sourced products tend to be more highly bioactive, likely due to

the fact that marine organisms have to retain their potency despite

being diluted in the surrounding sea-water".

Cultural services

Cultural

services relate to the non-material world, as they benefit the benefit

recreational, aesthetic, cognitive and spiritual activities, which are

not easily quantifiable in monetary terms.

Inspirational

Marine

environments have been used by many as an inspiration for their works

of art, music, architecture, traditions... Water environments are

spiritually important as a lot of people view them as a means for

rejuvenation and change of perspective. Many also consider the water as

being a part of their personality, especially if they have lived near it

since they were kids: they associate it to fond memories and past

experiences. Living near water bodies for a long time results in a

certain set of water activities that become a ritual in the lives of

people and of the culture in the region.

Recreation and tourism

Sea sports are very popular among coastal populations: surfing,

snorkeling, whale watching, kayaking, recreational fishing ... a lot of

tourists also travel to resorts close to the sea or rivers or lakes to

be able to experience these activities, and relax near the water. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 14 also has targets aimed at enhancing the use of ecosystem services for sustainable tourism especially in Small Island Developing States.

Beach accommodated into a recreational area.

Science and education

A

lot can be learned from marine processes, environments and organisms –

that could be implemented into our daily actions and into the scientific

domain. Although much is still yet to still be known about the ocean

world: "by the extraordinary intricacy and complexity of the marine

environment and how it is influenced by large spatial scales, time lags,

and cumulative effects".

Supporting services

Supporting

services are the services that allow for the other ecosystem services

to be present. They have indirect impacts on humans that last over a

long period of time. Several services can be considered as being both

supporting services and regulating/cultural/provisioning services.

Nutrient cycling

Nutrient cycling is the movement of nutrients through an ecosystem by biotic and abiotic processes.

The ocean is a vast storage pool for these nutrients, such as carbon,

nitrogen and phosphorus. The nutrients are absorbed by the basic

organisms of the marine food web and are thus transferred from one

organism to the other and from one ecosystem to the other. Nutrients are

recycled through the life cycle of organisms as they die and decompose,

releasing the nutrients into the neighboring environment. "The service

of nutrient cycling eventually impacts all other ecosystem services as

all living things require a constant supply of nutrients to survive".

Biologically mediated habitats

Biologically mediated habitats are defined as being the habitats that living marine structures offer to other organisms.

These need not to have evolved for the sole purpose of serving as a

habitat, but happen to become living quarters whilst growing naturally.

For example, coral reefs and mangrove forests are home to numerous

species of fish, seaweed and shellfish ... The importance of these

habitats is that they allow for interactions between different species,

aiding the provisioning of marine goods and services. They are also very

important for the growth at the early life stages of marine species

(breeding and bursary spaces), as they serve as a food source and as a

shelter from predators.

Coral and other living organisms serve as habitats for many marine species.

Primary production

Primary

production refers to the production of organic matter, i.e., chemically

bound energy, through processes such as photosynthesis and

chemosynthesis. The organic matter produced by primary producers forms

the basis of all food webs. Further, it generates oxygen (O2), a

molecule necessary to sustain animals and humans.

On average, a human consumes about 550 liter of oxygen per day, whereas

plants produce 1,5 liter of oxygen per 10 grams of growth.

Economics

Sustainable urban drainage pond

near housing in Scotland. The filtering and cleaning of surface and

waste water by natural vegetation is a form of ecosystem service.

There are questions regarding the environmental and economic values of ecosystem services.

Some people may be unaware of the environment in general and humanity's

interrelatedness with the natural environment, which may cause

misconceptions. Although environmental awareness is rapidly improving in

our contemporary world, ecosystem capital and its flow are still poorly

understood, threats continue to impose, and we suffer from the

so-called 'tragedy of the commons'.

Many efforts to inform decision-makers of current versus future costs

and benefits now involve organizing and translating scientific knowledge

to economics, which articulate the consequences of our choices in comparable units of impact on human well-being.

An especially challenging aspect of this process is that interpreting

ecological information collected from one spatial-temporal scale does

not necessarily mean it can be applied at another; understanding the

dynamics of ecological processes relative to ecosystem services is

essential in aiding economic decisions.

Weighting factors such as a service's irreplaceability or bundled

services can also allocate economic value such that goal attainment

becomes more efficient.

The economic valuation of ecosystem services also involves social

communication and information, areas that remain particularly

challenging and are the focus of many researchers.

In general, the idea is that although individuals make decisions for

any variety of reasons, trends reveal the aggregated preferences of a

society, from which the economic value of services can be inferred and

assigned. The six major methods for valuing ecosystem services in

monetary terms are:

- Avoided cost: Services allow society to avoid costs that would

have been incurred in the absence of those services (e.g. waste

treatment by wetland habitats avoids health costs)

- Replacement cost: Services could be replaced with man-made systems (e.g. restoration of the Catskill Watershed cost less than the construction of a water purification plant)

- Factor income: Services provide for the enhancement of incomes (e.g. improved water quality increases the commercial take of a fishery and improves the income of fishers)

- Travel cost: Service demand may require travel, whose costs can reflect the implied value of the service (e.g. value of ecotourism experience is at least what a visitor is willing to pay to get there)

- Hedonic pricing: Service demand may be reflected in the prices

people will pay for associated goods (e.g. coastal housing prices exceed

that of inland homes)

- Contingent valuation: Service demand may be elicited by posing

hypothetical scenarios that involve some valuation of alternatives (e.g.

visitors willing to pay for increased access to national parks)

A peer-reviewed study published in 1997 estimated the value of the

world's ecosystem services and natural capital to be between US$16 and

$54 trillion per year, with an average of US$33 trillion per year.

However, Salles (2011) indicated 'The total value of biodiversity is

infinite, so having debate about what is the total value of nature is

actually pointless because we can't live without it'.

As of 2012, many companies were not fully aware of the extent of

their dependence and impact on ecosystems and the possible

ramifications. Likewise, environmental management systems and

environmental due diligence tools are more suited to handle

"traditional" issues of pollution and natural resource consumption. Most focus on environmental impacts,

not dependence. Several tools and methodologies can help the private

sector value and assess ecosystem services, including Our Ecosystem, the 2008 Corporate Ecosystem Services Review, the Artificial Intelligence for Environment & Sustainability (ARIES) project from 2007, the Natural Value Initiative (2012) and InVEST (Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services & Tradeoffs, 2012)

Payments

Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES)

Payments for ecosystem services

(PES), also known as payments for environmental services (or benefits),

are incentives offered to farmers or landowners in exchange for

managing their land to provide some sort of ecological service. They

have been defined as "a transparent system for the additional provision

of environmental services through conditional payments to voluntary

providers". These programmes promote the conservation of natural resources in the marketplace.

Ecosystem services have no standardized definition but might broadly be called "the benefits of nature to households, communities, and economies" or, more simply, "the good things nature does". Twenty-four specific ecosystem services were identified and assessed by the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment,

a 2005 UN-sponsored report designed to assess the state of the world's

ecosystems. The report defined the broad categories of ecosystem

services as food production (in the form of crops, livestock, capture fisheries, aquaculture, and wild foods), fiber (in the form of timber, cotton, hemp, and silk), genetic resources (biochemicals, natural medicines, and pharmaceuticals), fresh water, air quality regulation, climate regulation, water regulation, erosion regulation, water purification and waste treatment, disease regulation, pest regulation, pollination, natural hazard regulation, and cultural services (including spiritual, religious, and aesthetic values, recreation and ecotourism).

Notably, however, there is a "big three" among these 24 services which

are currently receiving the most money and interest worldwide. These are

climate change mitigation,

watershed services and biodiversity conservation, and demand for these

services in particular is predicted to continue to grow as time goes on. One seminal 1997 Nature

magazine article estimated the annual value of global ecological

benefits at $33 trillion, a number nearly twice the gross global product

at the time.

In 2014, the author of this 1997 research (Robert Costanza) and a

qualified group of co-authors re-took this assessment – using only a

slightly modified methodology but with more detailed 2011 data – and

increased the aggregate global ecosystem services provisioning estimate

to $125–145 trillion a year. The same research project also estimated

between $4.3 and 20.2 trillion a year of losses to ecosystem services,

due to land use change.

PES has also been touted as a tool for rural development. In 2007, the World Bank released a document outlining the place of PES in development. But the link between the environment and development had been officially recognized long before with the 1972 Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment and later reaffirmed by the Rio Conference on Environment and Development.

However, it is important to note PES programs are usually not designed

to be primarily poverty alleviation schemes, although they may

incorporate development mechanisms.

Some PES programs involve contracts between consumers of ecosystem

services and the suppliers of these services. However, the majority of

the PES programs are funded by governments and involve intermediaries,

such as non-government organisations. The party supplying the

environmental services normally holds the

property rights

over an environmental good that provides a flow of benefits to the

demanding party in return for compensation. In the case of private

contracts, the beneficiaries of the

ecosystem

services are willing to pay a price that can be expected to be lower

than their welfare gain due to the services. The providers of the

ecosystem services can be expected to be willing to accept a payment

that is greater than the cost of providing the services.

Management and policy

Although

monetary pricing continues with respect to the valuation of ecosystem

services, the challenges in policy implementation and management are

significant and considerable. The administration of common pool resources has been a subject of extensive academic pursuit.[74][75][76][77][78]

From defining the problems to finding solutions that can be applied in

practical and sustainable ways, there is much to overcome. Considering

options must balance present and future human needs, and decision-makers

must frequently work from valid but incomplete information. Existing

legal policies are often considered insufficient since they typically

pertain to human health-based standards that are mismatched with

necessary means to protect ecosystem health and services. In 2000, to improve the information available, the implementation of an Ecosystem Services Framework has been suggested (ESF), which integrates the biophysical and socio-economic

dimensions of protecting the environment and is designed to guide

institutions through multidisciplinary information and jargon, helping

to direct strategic choices.

As of 2005 Local to regional collective management efforts were considered appropriate for services like crop pollination or resources like water.

Another approach that has become increasingly popular during the 1990s

is the marketing of ecosystem services protection. Payment and trading

of services is an emerging worldwide small-scale solution where one can

acquire credits for activities such as sponsoring the protection of

carbon sequestration sources or the restoration

of ecosystem service providers. In some cases, banks for handling such

credits have been established and conservation companies have even gone

public on stock exchanges, defining an evermore parallel link with

economic endeavors and opportunities for tying into social perceptions. However, crucial for implementation are clearly defined land rights, which are often lacking in many developing countries. In particular, many forest-rich developing countries suffering deforestation experience conflict between different forest stakeholders.

In addition, concerns for such global transactions include inconsistent

compensation for services or resources sacrificed elsewhere and

misconceived warrants for irresponsible use. As of 2001, another

approach focused on protecting ecosystem service biodiversity hotspots. Recognition that the conservation of many ecosystem services aligns with more traditional conservation goals (i.e. biodiversity)

has led to the suggested merging of objectives for maximizing their

mutual success. This may be particularly strategic when employing

networks that permit the flow of services across landscapes, and might also facilitate securing the financial means to protect services through a diversification of investors.

For example, as of 2013, there had been interest in the valuation of ecosystem services provided by shellfish production and restoration.

A keystone species, low in the food chain, bivalve shellfish such as

oysters support a complex community of species by performing a number of

functions essential to the diverse array of species that surround them.

There is also increasing recognition that some shellfish species may

impact or control many ecological processes; so much so that they are

included on the list of "ecosystem engineers"—organisms that physically,

biologically or chemically modify the environment around them in ways

that influence the health of other organisms.

Many of the ecological functions and processes performed or affected by

shellfish contribute to human well-being by providing a stream of

valuable ecosystem services over time by filtering out particulate

materials and potentially mitigating water quality issues by controlling

excess nutrients in the water.

As of 2018, the concept of ecosystem services had not been properly implemented into international and regional legislation yet.

Notwithstanding, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 15 has a target to ensure the conservation, restoration, and sustainable use of ecosystem services.

Ecosystem-based adaptation (EbA)

Ecosystem-based adaptation

or EbA is a strategy for community development and environmental

management that seeks to use an ecosystem services framework to help

communities adapt to the effects of climate change. The Convention on Biological Diversity

defines it as "the use of biodiversity and ecosystem services to help

people adapt to the adverse effects of climate change", which includes

the use of "sustainable management, conservation and restoration of

ecosystems, as part of an overall adaptation strategy that takes into

account the multiple social, economic and cultural co-benefits for local

communities".

In 2001, the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment announced that

humanity's impact on the natural world was increasing to levels never

before seen, and that the degradation of the planet's ecosystems would

become a major barrier to achieving the Millennium Development Goals.

In recognition of this fact, Ecosystem-Based Adaptation sought to use

the restoration of ecosystems as a stepping-stone to improve the quality

of life in communities experiencing the impacts of climate change.

Specifically, it involved the restoration of such ecosystems that

provide food and water and protection from storm surges and flooding. EbA interventions combine elements of both climate change mitigation and adaptation to global warming to help address the community's current and future needs.

Collaborative planning between scientists, policy makers, and

community members is an essential element of Ecosystem-Based Adaptation.

By drawing on the expertise of outside experts and local residents

alike, EbA seeks to develop unique solutions to unique problems, rather

than simply replicating past projects.

Land use change decisions

Ecosystem services decisions require making complex choices at the intersection of ecology, technology, society, and the economy. The process of making ecosystem services decisions must consider the interaction of many types of information, honor all stakeholder viewpoints, including regulatory agencies, proposal proponents, decision makers, residents, NGOs, and measure the impacts on all four parts of the intersection. These decisions are usually spatial, always multi-objective,

and based on uncertain data, models, and estimates. Often it is the

combination of the best science combined with the stakeholder values,

estimates and opinions that drive the process.

One analytical study modeled the stakeholders as agents

to support water resource management decisions in the Middle Rio Grande

basin of New Mexico. This study focused on modeling the stakeholder

inputs across a spatial decision, but ignored uncertainty. Another study used Monte Carlo

methods to exercise econometric models of landowner decisions in a

study of the effects of land-use change. Here the stakeholder inputs

were modeled as random effects to reflect the uncertainty. A third study used a Bayesian decision support system to both model the uncertainty in the scientific information Bayes Nets

and to assist collecting and fusing the input from stakeholders. This

study was about siting wave energy devices off the Oregon Coast, but

presents a general method for managing uncertain spatial science and

stakeholder information in a decision making environment. Remote sensing

data and analyses can be used to assess the health and extent of land

cover classes that provide ecosystem services, which aids in planning,

management, monitoring of stakeholders' actions, and communication

between stakeholders.

In Baltic countries scientists, nature conservationists and local

authorities are implementing integrated planning approach for grassland

ecosystems. They are developing an integrated planning tool based on GIS

(geographic information system) technology and put online that will

help for planners to choose the best grassland management solution for

concrete grassland. It will look holistically at the processes in the

countryside and help to find best grassland management solutions by

taking into account both natural and socioeconomic factors of the

particular site.

History

While the notion of human dependence on Earth's ecosystems reaches to the start of Homo sapiens' existence, the term 'natural capital' was first coined by E. F. Schumacher in 1973 in his book Small is Beautiful. Recognition of how ecosystems could provide complex services to humankind date back to at least Plato (c. 400 BC) who understood that deforestation could lead to soil erosion and the drying of springs.

Modern ideas of ecosystem services probably began when Marsh

challenged in 1864 the idea that Earth's natural resources are unbounded

by pointing out changes in soil fertility in the Mediterranean. It was not until the late 1940s that three key authors—Henry Fairfield Osborn, Jr, William Vogt, and Aldo Leopold—promoted recognition of human dependence on the environment.

In 1956, Paul Sears drew attention to the critical role of the ecosystem in processing wastes and recycling nutrients. In 1970, Paul Ehrlich and Rosa Weigert called attention to "ecological systems" in their environmental science textbook

and "the most subtle and dangerous threat to man's existence ... the

potential destruction, by man's own activities, of those ecological

systems upon which the very existence of the human species depends".

The term "environmental services" was introduced in a 1970 report of the Study of Critical Environmental Problems, which listed services including insect pollination, fisheries, climate regulation and flood

control. In following years, variations of the term were used, but

eventually 'ecosystem services' became the standard in scientific

literature.

The ecosystem services concept has continued to expand and includes socio-economic and conservation

objectives, which are discussed below. A history of the concepts and

terminology of ecosystem services as of 1997, can be found in Daily's

book "Nature's Services: Societal Dependence on Natural Ecosystems".

While Gretchen Daily's original definition distinguished between ecosystem goods and ecosystem services, Robert Costanza and colleagues' later work and that of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment lumped all of these together as ecosystem services.

Examples

The

following examples illustrate the relationships between humans and

natural ecosystems through the services derived from them:

- The US military has funded research through the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory,

which claims that Department of Defense lands and military

installations provide substantial ecosystem services to local

communities, including benefits to carbon storage, resiliency to

climate, and endangered species habitat. As of 2020, research from Duke University claims for example Eglin Air Force Base provides about $110 million in ecosystem services per year, $40 million more than if no base was present.

- In New York City, where the quality of drinking water had fallen below standards required by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), authorities opted to restore the polluted Catskill Watershed

that had previously provided the city with the ecosystem service of

water purification. Once the input of sewage and pesticides to the watershed area was reduced, natural abiotic processes such as soil absorption and filtration of chemicals, together with biotic recycling via root systems and soil microorganisms, water quality improved to levels that met government standards. The cost of this investment in natural capital was estimated at $1–1.5 billion, which contrasted dramatically with the estimated $6–8 billion cost of constructing a water filtration plant plus the $300 million annual running costs.

- Pollination of crops by bees is required for 15–30% of U.S. food production; most large-scale farmers import non-native honey bees to provide this service. A 2005 study

reported that in California's agricultural region, it was found that

wild bees alone could provide partial or complete pollination services

or enhance the services provided by honey bees through behavioral

interactions. However, intensified agricultural practices

can quickly erode pollination services through the loss of species. The

remaining species are unable to compensate this. The results of this

study also indicate that the proportion of chaparral and oak-woodland habitat available for wild bees within 1–2 km of a farm

can stabilize and enhance the provision of pollination services. The

presence of such ecosystem elements functions almost like an insurance

policy for farmers.

- In watersheds of the Yangtze River in China, spatial models for water flow through different forest habitats were created to determine potential contributions for hydroelectric power

in the region. By quantifying the relative value of ecological

parameters (vegetation-soil-slope complexes), researchers were able to

estimate the annual economic benefit of maintaining forests in the

watershed for power services to be 2.2 times that if it were harvested

once for timber.

- In the 1980s, mineral water company Vittel

(now a brand of Nestlé Waters) faced the problem that nitrate and

pesticides were entering the company's springs in northeastern France.

Local farmers had intensified agricultural practices and cleared native

vegetation that previously had filtered water before it seeped into the

aquifer used by Vittel. This contamination threatened the company's

right to use the "natural mineral water" label under French law.

In response to this business risk, Vittel developed an incentive

package for farmers to improve their agricultural practices and

consequently reduce water pollution that had affected Vittel's product.

For example, Vittel provided subsidies and free technical assistance to

farmers in exchange for farmers' agreement to enhance pasture

management, reforest catchments, and reduce the use of agrochemicals, an

example of a payment for ecosystem services program.

- In 2016, it was counted that to plant 15 000 ha new woodland in the

UK, considering only the value of timber, it would cost £79 000 000,

which is more than the benefit of £65 000 000. If, however, all other

benefits the trees in lowland could provide (like soil stabilization,

wind deflection, recreation, food production, air purification, carbon

storage, wildlife habitat, fuel production, cooling, flood prevention)

were included, the costs will increase due to displacing the profitable

farmland (would be around £231 000 000) but would be overweight by

benefits of £546 000 000.

- In Europe, various projects are implemented in order to define the

values of concrete ecosystems and to implement this concept into

decision-making process. For example, "LIFE Viva grass" project aims to

do this with grasslands in Baltics.