| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 25,694,928[1][2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Mexico (Yucatán, Oaxaca, Chiapas, Campeche, Veracruz, Guerrero) | |

| Languages | |

| Nahuatl, Yucatec, Tzotzil, Mixtec, Zapotec, Otomi, Huichol, Totonac and other living 54 languages along the Mexican territory, as well as Spanish | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity (predominantly Roman Catholic, with Amerindian religious elements, including Aztec and Mayan religion) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Indigenous peoples of the Americas |

Indigenous peoples of Mexico (Spanish: pueblos indígenas de México), Native Mexicans (Spanish: nativos mexicanos), or Mexican Native Americans (Spanish: Mexicanos nativo americanos), are those who are part of communities that trace their roots back to populations and communities that existed in what is now Mexico prior to the arrival of Europeans.

According to the National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples (Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas, or CDI in Spanish) and the INEGI (official census institute), in 2015, 25,694,928 people in Mexico self-identify as being indigenous[3][4] of many different ethnic groups,[5] which constitute 21.5% of Mexico's population.[1][2]

Definition

The number of indigenous Mexicans is judged using the political criteria found in the 2nd article of the Mexican constitution. The Mexican census does not report racial-ethnicity but only the cultural-ethnicity of indigenous communities that preserve their indigenous languages, traditions, beliefs and cultures.[8]

The category of indigena (indigenous) can be defined narrowly according to linguistic criteria including only persons that speak one of Mexico's 89 indigenous languages, this is the categorization used by the National Mexican Institute of Statistics. It can also be defined broadly to include all persons who self identify as having an indigenous cultural background, whether or not they speak the language of the indigenous group they identify with. This means that the percentage of the Mexican population defined as "indigenous" varies according to the definition applied; cultural activists have referred to the usage of the narrow definition of the term for census purposes as "statistical genocide".

The indigenous peoples in Mexico have the right of free determination under the second article of the constitution. According to this article the indigenous peoples are granted:

- the right to decide the internal forms of social, economic, political, and cultural organization;

- the right to apply their own normative systems of regulation as long as human rights and gender equality are respected;

- the right to preserve and enrich their languages and cultures;

- the right to elect representatives before the municipal council where their territories are located;

History of the Indigenous Peoples

Pre-Columbian civilizations

Mesoamerica and its cultural areas

Map of major prehispanic archaeological sites in Northwest Mexico and the US Southwest

The prehispanic civilizations of what now is known as Mexico are usually divided in two regions: Mesoamerica, in reference to the cultural area where several complex civilizations developed before the arrival of the Spanish in the sixteenth century, and Aridoamerica (or simply "The North")[15] in reference to the arid region north of the Tropic of Cancer where few civilizations developed and was mostly inhabited by nomadic or semi-nomadic groups.[citation needed] Despite the conditions however, it is argued that the Mogollon culture and Peoples successfully established population centers at Casas Grandes and Cuarenta Casas in a vast territory that encompassed northern Chihuahua state and parts of Arizona and New Mexico in the United States.

Mesoamerica was densely populated by diverse indigenous ethnic groups[15][page needed][16] which, although sharing common cultural characteristics, spoke different languages and developed unique civilizations.

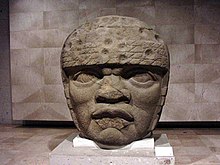

One of the most influential civilizations that developed in Mesoamerica was the Olmec civilization, sometimes referred to as the "Mother Culture of Mesoamerica".[16] The later civilization in Teotihuacán reached its peak around 600 AD, when the city became the sixth largest city in the world,[16] whose cultural and theological systems influenced the Toltec and Aztec civilizations in later centuries. Evidence has been found on the existence of multiracial communities or neighborhoods in Teotihuacan (and other large urban areas like Tenochtitlan).[17][18]

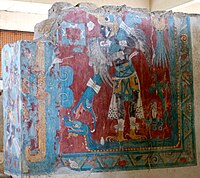

The Maya civilization, though also influenced by other Mesoamerican civilizations, developed a vast cultural region in south-east Mexico and northern Central America, while the Zapotec and Mixtec culture dominated the valley of Oaxaca, and the Purépecha in western Mexico.

Trade

There is common academic agreement that significant systems of trading existed between the cultures of Mesoamerica, Aridoamerica and the American Southwest, and the architectural remains and artifacts share a commonality of knowledge attributed to this trade network. The routes stretched far into Mesoamerica and reached as far north to ancient communities that included such population centers in the United States such as at Snaketown,[19] Chaco Canyon, and Ridge Ruin near Flagstaff (considered some of the finest artifacts ever located).Colonial era

A 16th-century manuscript illustrating La Malinche and the contact of Spaniards and Aztecs.

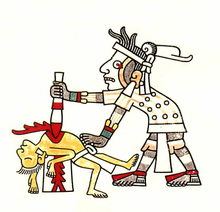

By the time of the arrival of the Spanish in central Mexico, many of the diverse ethnic civilizations (with the notable exception of the Tlaxcaltecs and the Purépecha Kingdom of Michoacán) were loosely joined under the Aztec Empire, the last Nahua civilization to flourish in Central Mexico. The capital of the empire, Tenochtitlan, became one of the largest urban centers in the world, with an estimated population of 350,000 inhabitants.[15][page needed]

During the conquest of the Aztec Empire, the Spanish conquistadors, vastly outnumbered by indigenous peoples, used the ethnic diversity of the country and exploited the discontentment of the subjugated groups, making important alliances with rivals of the Aztecs.[15][page needed] While the alliances were decisive to the Europeans' victory, the indigenous peoples were soon subjugated by an equally impressive empire. However, as the Spanish consolidated their rule in what became the viceroyalty of New Spain, the crown recognized the indigenous nobility in Mesoamerica as nobles and kept the existing basic structure of indigenous city-states. Indigenous communities were incorporated as communities under Spanish rule and with the indigenous power structure largely intact.[20]

As part of the Spanish incorporation of indigenous into the colonial system, the friars taught indigenous scribes to write their languages in Latin letters so that there are huge corpus of colonial-era documentation in the Nahuatl language, Mixtec, Zapotec, and Yucatec Maya as well as others. Such a written tradition likely took hold because there was an existing tradition of pictorial writing found in many indigenous codices. Scholars have utilized the colonial-era alphabetic documentation in what is currently called the New Philology to illuminate the colonial experience of Mesoamerican peoples from their own viewpoints.[21]

Since Mesoamerican peoples had an existing requirement of labor duty and tribute in the pre-conquest era, Spaniards who were awarded the labor and tribute of particular communities in encomienda could benefit financially. Indigenous officials in their communities were involved in maintaining this system. There was a precipitous decline in indigenous populations due to the spread of European diseases previously unknown in the New World. Pandemics wrought havoc, but indigenous communities recovered with fewer members.[15][page needed][22][23]

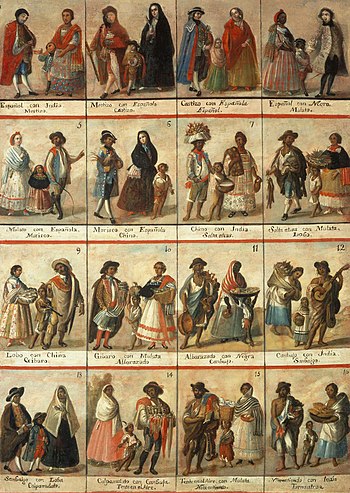

With contact between Europeans, the black slaves that they brought, and indigenous populations, there was intermingling of the groups, with mixed-race castas, particularly mestizos, becoming a component of Spanish cities and to a lesser extent indigenous communities. The Spanish legal structure formally separated what they called the república de indios (the republic of Indians) from the república de españoles (republic of Spaniards), the latter of which encompassed all those in the Hispanic sphere: Europeans, Africans, and mixed-race castas. Although in many ways indigenous peoples were marginalized in the colonial system,[24] the paternalistic structure of colonial rule supported the continued existence and structure of indigenous communities. The Spanish crown recognized the existing ruling group, gave protection to the land holdings of indigenous communities, and communities' and individuals had access to the Spanish legal system.[22][23][25] In practice in central Mexico this meant that until the nineteenth-century liberal reform that eliminated the corporate status of indigenous communities, indigenous communities had a protected status.

Although the crown recognized the political structures and the ruling elites in the civil sphere, in the religious sphere indigenous men were banned from the Christian priesthood, following an early Franciscan experiment that included fray Bernardino de Sahagún at the Colegio de Santa Cruz Tlatelolco to train such a group. Mendicants of the Franciscan, Dominican, and Augustinian orders initially evangelized indigenous in their own communities in what is often called the "spiritual conquest".[26] Later on the northern frontiers where nomadic indigenous groups had no fixed settlements, the Spanish created missions and settled indigenous populations in these complexes. The Jesuits were prominent in this enterprise until their expulsion from Spanish America in 1767. Catholicism with particular local aspects was the only permissible religion in the colonial era.

Independence to the Mexican Revolution

Flag of the Mexican republic

Comanchería in the 19th century

The insurgency against the Spanish Empire was a decade-long struggle ending in 1821, in which indigenous peoples participated for their own motivations.[27] When New Spain became independent, the new country was named after its capital city, Mexico City. The new flag of the country had at its center a symbol of the Aztecs, an eagle perched on a nopal cactus. Mexico declared the abolition of black slavery in 1829 and the equality of all citizens under the law. Indigenous communities continued to have rights as corporations to maintain land holdings until the liberal Reforma. Some indigenous individuals integrated into the Mexican society, like Benito Juárez of Zapotec ethnicity, the first indigenous president of a country in the New World.[28] As a political liberal, however, Juárez supported the removal of protections of indigenous community corporate land holding.

In the arid North of Mexico, indigenous peoples, such as the Comanche and Apache, who had acquired the horse, were able to wage successful warfare against the Mexican state. The Comanche controlled considerable territory, called the Comancheria.[29] The Yaqui also had a long tradition of resistance, with the late nineteenth-century leader Cajemé being prominent. The Mayo joined their Yaqui neighbors in rebellion after 1867.

In Yucatan, Mayas waged a protracted war against local Mexican control in the Caste War of Yucatán, which was most intensely fought in 1847, but lasted until 1901.[30]

20th century

The greatest change came about as a result of the Mexican Revolution, a violent social and cultural movement that defined 20th century Mexico. The Revolution produced a national sentiment that the indigenous peoples were the foundation of Mexican society. Several prominent artists promoted the "Indigenous Sentiment" (sentimiento indigenista) of the country, including Frida Kahlo, and Diego Rivera. Throughout the twentieth century, the government established bilingual education in certain indigenous communities and published free bilingual textbooks.[31] Some states of the federation appropriated an indigenous inheritance in order to reinforce their identity.[32]

In spite of the official recognition of the indigenous peoples, the economic underdevelopment of the communities, accentuated by the crises of the 1980s and 1990s, has not allowed for the social and cultural development of most indigenous communities.[33] Thousands of indigenous Mexicans have emigrated to urban centers in Mexico as well as in the United States. In Los Angeles, for example, the Mexican government has established electronic access to some of the consular services provided in Spanish as well as Zapotec and Mixe.[34] Some of the Maya peoples of Chiapas have revolted, demanding better social and economic opportunities, requests voiced by the EZLN.[citation needed]

The Chiapas conflict of 1994 led to collaboration between the Mexican government and the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, an indigenous political group.[35] This large movement generated international media attention and united many indigenous groups.[36] In 1996 the San Andrés Larráinzar Accords were negotiated between the Zapatista Army of National Liberation and the Mexican government.[35] The San Andres accords were the first time that indigenous rights were acknowledged by the Mexican government.[35]

The government has made certain legislative changes to promote the development of the rural and indigenous communities and the preservation and promotion of their languages. The second article of the Constitution was modified to grant them the right of self-determination and requires state governments to promote and ensure the economic development of the indigenous communities as well as the preservation of their languages and traditions.

Rights of indigenous peoples

List of rights

The Spanish crown had legal protections of indigenous as individuals as well as their communities, including establishing a separate General Indian Court.[37] The mid-nineteenth century liberal reform removed those, so that there was equality of individuals before Mexican law.[38] The creation of a national identity not linked to racial or ethnic identity was an aim of Mexican liberalism.In the late twentieth century there has been a push for indigenous rights and a recognition of indigenous cultural identity. According to the constitutional reform of 2001, the following rights of indigenous peoples are recognized:[39]

- acknowledgement as indigenous communities, right to self-ascription, and the application of their own regulatory systems

- preservation of their cultural identity, land, consultation and participation

- access to the jurisdiction to the state and to development

- recognition of indigenous peoples and communities as subject of public law

- self-determination and self-autonomy

- remunicipalization for the advancement of indigenous communities

- administer own forms of communication and media

Land rights

An 18th century depiction of the casta racial classification system created by the Spanish. The painting is in the Museo de Virreinato, Tepozotlan.

During the early colonial era in central Mexico, Spaniards were more interested in having access to indigenous labor than in ownership of land. The institution of the encomienda, a crown grant of the labor of particular indigenous communities to individuals was a key element of the imposition of Spanish rule, with the land tenure of indigenous communities continuing largely in its preconquest form. The Spanish crown initially kept intact the indigenous sociopolitical system of local rulers and land tenure, with the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire eliminating the superstructure of rule, replacing it with Spanish.[40][41] The crown had several concerns about the encomienda. First was that the holders of encomiendas, called encomenderos were becoming too powerful, essentially a seigneurial group that might challenge crown power (as shown in the conspiracy by conqueror Hernán Cortés's legitimate son and heir). Second was that the encomenderos were monopolizing indigenous labor to the exclusion of newly arriving Spaniards. And third, the crown was concerned about the damage to the indigenous vassals of the crown and their communities by the institution. Through the New Laws of 1542, the crown sought to phase out the encomienda and replace it with another crown mechanism of forced indigenous labor, known as the repartimiento. Indigenous labor was no longer monopolized by a small group of privileged encomienda holders, but rather labor was apportioned to a larger group of Spaniards. Natives performed low-paid or underpaid labor for a certain number of weeks or months on Spanish enterprises.[42]

The land of indigenous peoples is used for material reasons as well as spiritual reasons. Religious, cultural, social, spiritual, and other events relating to their identity are also tied to the land.[43] Indigenous people use collective property so that the aforementioned services that the land provides are available to the entire community and future generations.[43] This was a stark contrast to the viewpoints of colonists that saw the land purely in an economic way where land could be transferred between individuals.[43] Once the land of the indigenous people and therefore their livelihood was taken from them, they became dependent on those that had land and power.[43] Additionally, the spiritual services that the land provided were no longer available and caused a deterioration of indigenous groups and cultures.[43]

Colonial-era racial categories and post-independence

The Spanish legal system divided racial groups into two basic categories, the República de Españoles, consisting of all non-indigenous but initially white Spaniards and black Africans, and the República de Indios. As there was greater intermixture and resulting offspring, a more formal casta system came into place, with specific terms for different racial mixtures. This system gave more political and social power to Spaniards so that Indigenous people and blacks could be kept in lower positions.[44] When the ethnic origins of the person were not known, phenotypic characteristics were relied upon to determine the status of the individual.[44] Those that were in lower statuses had to pay more to the crown.[44]When Mexico gained independence in 1821, the casta system was eliminated as a legal structure, but racial divides remained. White Mexican argued about what the solution was to the Indian Problem, that is indigenous who continued to live in communities and were not integrated politically or socially as citizens of the new republic.[45] The Mexican constitution of 1824 has several articles pertaining to indigenous peoples. The second article of the constitution of Mexico recognizes and enforces the right of indigenous peoples and communities to self-determination and therefore their autonomy to:

V. Preserve and improve their habitat as well as preserve the integrity of their lands in accordance with this constitution. VI. Be entitled to the estate and land property modalities established by this constitution and its derived legislation, to all private property rights and communal property rights as well as to use and enjoy in a preferential way all the natural resources located at the places which the communities live in, except those defined as strategic areas according to the constitution. The communities shall be authorized to associate with each other in order to achieve such goals.[46]

Under the Mexican government, some indigenous people had land rights under ejido and agrarian communities.[47] Under ejidos, indigenous communities have usufruct rights of the land. Indigenous communities choose to do this when they do not have the legal evidence to claim the land. In 1992, shifts were made to the economic structure and ejidos could now be partitioned and sold. For this to happen, the PROCEDE program was established. The PROCEDE program surveyed, mapped, and verified the ejido lands. This privatization of land undermined the economic base of the indigenous communities much like the taking of their land during colonization.[47]

Linguistic rights

The history of linguistic rights in Mexico began when Spanish first made contact with Indigenous Languages during the colonial period.[35] During the early sixteenth century mestizaje, mixing of races of culture, led to mixing of languages as well.[35] The Spanish Crown proclaimed Spanish to be the language of the empire; however, indigenous languages were used during conversion of individuals to Catholicism.[35] Because of this, indigenous languages were more widespread than Spanish from 1523-1581.[35] During the late sixteenth century, the status of Spanish language increased.[35]By the seventeenth century, the elite minority were Spanish speakers.[35] After independence in 1821 there was a shift to Spanish to legitimize the Mexican Spanish created by the Mexican criollos.[35] Since then, indigenous tongues were discriminated against and seen as not modern.[48] The nineteenth century brought with it programs to provide bilingual education at primary levels where they would eventually transition to Spanish only education.[35] Linguistic uniformity was sought out to strengthen national identity; however, this left indigenous languages out of power structures.[35]

Sign

indicating the entrance of Zapatista rebel territory. "You are in

Zapatista territory in rebellion. Here the people command and the

government obeys".

The Chiapas conflict of 1994 led to collaboration between the Mexican government and the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, an indigenous political group.[35] In 1996 the San Andrés Larráinzar Accords were negotiated between the Zapatista Army of National Liberation and the Mexican government.[35] The San Andres accords were the first time that indigenous rights were acknowledged by the Mexican government.[35] The San Andres Accords did not explicitly state language but language was involved in matters involving culture and education.[35]

In 2001, the constitution of Mexico was changed to acknowledge indigenous peoples and grant them protection. The second article of the constitution of Mexico recognizes and enforces the right of indigenous peoples and communities to self-determination and therefore their autonomy to:

- Preserve and enrich their language, knowledge, and every part of their culture and identity.[46]

However, there has been a lack of enforcement of the law. For example, the General Law on Linguistic Rights of Indigenous People guarantees the right to a trial in the language of indigenous peoples with someone who understands their culture.[49] According to the National Human Rights Commission (Mexico), Mexico has not abided by this law.[48] Examples of this include Jacinta Francisca Marcial, an indigenous woman who was imprisoned for kidnapping in 2006.[48] After three years and the assistance of Amnesty International she was released for lack of evidence.[48]

Additionally, the General Law on Linguistics also guarantees bilingual and intercultural education.[49] However, it is a common complaint that teachers do not know the indigenous language or do not prioritize teaching the indigenous language.[48] In fact, some studies argue that formal education has decreased the prevalence of indigenous languages.[48]

Some parents do not teach their children their indigenous language and some children refuse to learn their indigenous language for fear that they will be discriminated against. Scholars argue that there needs to be a social change to elevate the status of indigenous languages in order for the law to be withheld so that indigenous languages are protected.[48]

Rights of indigenous women

Indigenous women are often taken advantage of because they are women, indigenous, and often poor.[50] Indigenous culture has been used as a pretext for Mexican government to enact laws that deny human rights to women such as the right to own land.[50] Additionally, violence against women has been regarded by the Mexican government as a cultural practice.[50] The government has enforced impunity of the exploitation of indigenous women by its own government[clarification needed] including by the military.[50]The EZLN accepted a Revolutionary Law for Women on March 8, 1993.[50] The law is not fully enforced but shows solidarity between the indigenous movement and women.[50] The Mexican government has increased militarization of indigenous areas which makes women more susceptible to harassment through military abuses.[50]

Indigenous women are forming many organizations to support each other, improve their position in society, and gain financial independence.[50] Indigenous women use national and international legislation to support their claims that go against cultural norms such as domestic violence.[51]

Reproductive justice is an important issue to indigenous communities because there is a lack of development in these areas and is less access to maternal care. Conditional cash transfer programs such as Oportunidades have been used to encourage indigenous women to seek formal health care.[52]

Demographics

Indigenous

people from all parts of Mexican state of Oaxaca, participate wearing

traditional clothes and artifacts, in a celebration known as Guelaguetza.

Definition

The number of indigenous Mexicans is judged using the political criteria found in the 2nd article of the Mexican constitution. The Mexican census does not report racial-ethnicity but only the cultural-ethnicity of indigenous communities that preserve their indigenous languages, traditions, beliefs, and cultures.[8]Languages

The Law of Linguistic Rights of the Indigenous Languages recognizes 62 indigenous languages as "national languages" which have the same validity as Spanish in all territories where they are spoken.[11] According to the National Institute of Statistics, Geography and Data Processing (INEGI), approximately 6.7% of the population speaks an indigenous language.[53] That is, less than half of those identified as indigenous.[54] 6,695,228 people 5 years or older were tallied as indigenous-language speakers in the 2010 census, an increase of about 650,000 from the 2000 census. In 2000, 6,044,547 people 5 years or older spoke an indigenous language.[55]In previous censuses, information on the indigenous speaking population five years of age and older was obtained from the Mexican people. However, in the 2010 census, this approach was changed and the Government also began to collect data on people 3 years and older because from the age of 3, children are able to communicate verbally. With this new approach, it was determined that there were 6,913,362 people 3 years of age or more who spoke an indigenous language (218,000 children 3 and 4 four years of age fell into this category), accounting for 6.6% of the total population. The population of children aged 0 to 2 years in homes where the head of household or a spouse spoke an indigenous language was 678 954. The indigenous language speaking population has been increasing in absolute numbers for decades, but have nonetheless been falling in proportion to the national population.[54]

The recognition of indigenous languages and the protection of indigenous cultures is granted not only to the ethnic groups indigenous to modern-day Mexican territory, but also to other North American indigenous groups that migrated to Mexico from the United States[13] in the nineteenth century and those who immigrated from Guatemala in the 1980s.[1][2][14]

States

The five states with the largest indigenous-language-speaking populations are:- Oaxaca, with 1,165,186 indigenous language speakers, accounting for 34.2% of the state's population.

- Chiapas, with 1,141,499 indigenous language speakers, accounting for 27.2% of the state's population.

- Veracruz, with 644,559 indigenous language speakers, accounting for 9.4% the state's population.

- Puebla, with 601,680 indigenous language speakers, accounting for 11.7% of the state's population.

- Yucatán, with 537,516 indigenous language speakers, accounting for 30.3% of the state's population.

Population statistics

Indigenous Population Percentage of Mexico by State 2015

Mexican states by percentage indigenous, 2010.

Mexican states by total indigenous population, 2010.

According to the National Commission for the Development of the Indigenous Peoples (CDI), there were 25,694,928 indigenous people reported in Mexico in 2015,[1][2] which constitutes 21.5% of the population of Mexico. This is a significant increase from the 2010 census, in which indigenous Mexicans accounted for 14.9% of the population, and numbered 15,700,000[56] Most indigenous communities have a degree of financial, political autonomy under the legislation of "usos y costumbres", which allows them to regulate internal issues under customary law.

The indigenous population of Mexico has in recent decades increased both in absolute numbers as-well as a percentage of the population. This is largely due to increased self-identification as indigenous, as-well as indigenous women having higher birth rates as compared to the Mexican average.[2][12][57][58] Indigenous peoples are more likely to live in more rural areas, than the Mexican average, but many do reside in urban or suburban areas, particularly, in the central states of Mexico, Puebla, Tlaxcala, the Federal District and the Yucatán Peninsula.

According to the CDI, the states with the greatest percentage of indigenous population are:[59] Yucatán, with 65.40%, Quintana Roo with 44.44% and Campeche with 44.54% of the population being indigenous, most of them Maya; Oaxaca with 65.73% of the population, the most numerous groups being the Mixtec and Zapotec peoples; Chiapas has 36.15%, the majority being Tzeltal and Tzotzil Maya; Hidalgo with 36.21%, the majority being Otomi; Puebla with 35.28%, and Guerrero with 33.92%, mostly Nahua people and the states of San Luis Potosí and Veracruz both home to a population of 19% indigenous people, mostly from the Totonac, Nahua and Teenek (Huastec) groups.

States

The majority of the indigenous population is concentrated in the central and southern states. According to the CDI, the states with the greatest percentage of indigenous population as of 2015 are:- Oaxaca, 65.73%

- Yucatán, 65.40%

- Campeche, 44.54%

- Quintana Roo, 44.44%

- Hidalgo, 36.21%

- Chiapas, 36.15%

- Puebla, 35.28%

- Guerrero, 33.92%

- Veracruz, 29.25%

- Morelos, 28.11%

- Michoacán, 27.69%

- Tabasco, 25.77%

- Tlaxcala, 25.24%

- San Luis Potosí, 23.20%

- Nayarit, 22.18%

- Colima, 20.43%

- Querétaro, 19.17%

- Sonora, 17.83%

- State of Mexico, 17.00%

- Baja California Sur, 14.47%

- Sinaloa, 12.83%

- Aguascalientes, 11.69%

- Chihuahua, 11.28%

- Jalisco, 11.12%

- Guanajuato, 9.13%

- Distrito Federal, 8.80%

- Baja California, 8.54%

- Durango, 7.94%

- Zacatecas, 7.61%

- Coahuila, 6.93%

- Nuevo León, 6.88%

- Tamaulipas, 6.30%

Population genetics

In 2011 a large scale mitochondrial sequencing in Mexican Americans revealed 85 to 90% of maternal mtDNA lineages are of Native American origin, with the remainder having European (5-7%) or African ancestry (3-5%). Thus the observed frequency of Native American mtDNA in Mexican/Mexican Americans is higher than was expected on the basis of autosomal estimates of Native American admixture for these populations i.e. ~ 30-46%[61]| Amerindian (Mexico) Reference Population | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

5%

87%

4%

2%

| |||||||||||||

| Finland & Northern Siberia | Native American | ||||||||||||

| Southern Europe | Western & Central Africa | ||||||||||||

| "This population is based on samples collected from regions in central Mexico. These are the descendants of the original settlers of the Americas over 15,000 years ago, accounting for the large Native American percentage. The Finland and Siberia component is reflective of the origins of the Native Americans in northeastern Asia over 20,000 years ago, while the European components reflect the influence of Spanish colonization on Mesoamerica." | |||||||||||||

Development and socio-economic indicators

Mexican States by Human Development Index, 2015.

Generally, indigenous Mexicans live more poorly than non-indigenous Mexicans however, social development varies between states, different indigenous ethnicities and between rural and urban areas. In all states indigenous people have higher infant mortality, in some states almost double of the non-indigenous populations.[63]

Some indigenous groups, particularly the Yucatec Maya in the Yucatán peninsula[64][65] and some of the Nahua and Otomi peoples in central states have maintained higher levels of development while indigenous peoples in states such as the Guerrero[66] or Michoacán[67] are ranked drastically lower than the average Mexican citizen in these fields. Despite certain indigenous groups such as the Maya or Nahua retaining high levels of development, the general indigenous population lives at a lower level of development than the general population.

Literacy rates are much lower for the indigenous, particularly in the southwestern states of Guerrero and Oaxaca due lack of access to education and a lack of the educational literature available in indigenous languages. Literacy rates are also much lower, with 27% of indigenous children between 6 and 14 being illiterate compared to a national average of 12%.[63] The Mexican government is obligated to provide education in indigenous languages, but many times fails to provide schooling in languages other than Spanish. As a result, many indigenous groups have resorted to creating their own small community educational institutions.

The indigenous population participate in the workforce longer than the national average, starting earlier and continuing longer. A major reason for this is that significant number of the indigenous practice economically under productive agriculture and receive no regular salaries. Indigenous people also have less access to health care.