A tradition is a belief or behavior (folk custom) passed down within a group or society with symbolic meaning or special significance with origins in the past. A component of cultural expressions and folklore, common examples include holidays or impractical but socially meaningful clothes (like lawyers' wigs or military officers' spurs), but the idea has also been applied to social norms such as greetings. Traditions can persist and evolve for thousands of years—the word tradition itself derives from the Latin tradere literally meaning to transmit, to hand over, to give for safekeeping. While it is commonly assumed that traditions have an ancient history, many traditions have been invented on purpose, whether that be political or cultural, over short periods of time. Various academic disciplines also use the word in a variety of ways.

The phrase "according to tradition", or "by tradition", usually means that whatever information follows is known only by oral tradition, but is not supported (and perhaps may be refuted) by physical documentation, by a physical artifact, or other quality evidence. Tradition is used to indicate the quality of a piece of information being discussed. For example, "According to tradition, Homer was born on Chios, but many other locales have historically claimed him as theirs." This tradition may never be proven or disproven. In another example, "King Arthur, by tradition a true British king, has inspired many well loved stories." Whether they are documented fact or not does not decrease their value as cultural history and literature.

Traditions are a subject of study in several academic fields, especially in social sciences such as folklore studies, anthropology, archaeology, and biology.

The concept of tradition, as the notion of holding on to a previous time, is also found in political and philosophical discourse. For example, it is the basis of the political concept of traditionalism, and also strands of many world religions including traditional Catholicism. In artistic contexts, tradition is used to decide the correct display of an art form. For example, in the performance of traditional genres (such as traditional dance), adherence to guidelines dictating how an art form should be composed are given greater importance than the performer's own preferences. A number of factors can exacerbate the loss of tradition, including industrialization, globalization, and the assimilation or marginalization of specific cultural groups. In response to this, tradition-preservation attempts have now been started in many countries around the world, focusing on aspects such as traditional languages. Tradition is usually contrasted with the goal of modernity and should be differentiated from customs, conventions, laws, norms, routines, rules and similar concepts.

Definition

The English word tradition comes from the Latin traditio via French, the noun from the verb tradere (to transmit, to hand over, to give for safekeeping); it was originally used in Roman law to refer to the concept of legal transfers and inheritance. According to Anthony Giddens and others, the modern meaning of tradition evolved during the Enlightenment period, in opposition to modernity and progress.

As with many other generic terms, there are many definitions of tradition. The concept includes a number of interrelated ideas; the unifying one is that tradition refers to beliefs, objects or customs performed or believed in the past, originating in it, transmitted through time by being taught by one generation to the next, and are performed or believed in the present.

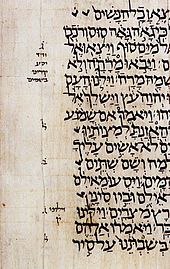

Tradition can also refer to beliefs or customs that are Prehistoric, with lost or arcane origins, existing from time immemorial. Originally, traditions were passed orally, without the need for a writing system. Tools to aid this process include poetic devices such as rhyme and alliteration. The stories thus preserved are also referred to as tradition, or as part of an oral tradition. Even such traditions, however, are presumed to have originated (been "invented" by humans) at some point. Traditions are often presumed to be ancient, unalterable, and deeply important, though they may sometimes be much less "natural" than is presumed. It is presumed that at least two transmissions over three generations are required for a practice, belief or object to be seen as traditional. Some traditions were deliberately invented for one reason or another, often to highlight or enhance the importance of a certain institution. Traditions may also be adapted to suit the needs of the day, and the changes can become accepted as a part of the ancient tradition. Tradition changes slowly, with changes from one generation to the next being seen as significant. Thus, those carrying out the traditions will not be consciously aware of the change, and even if a tradition undergoes major changes over many generations, it will be seen as unchanged.

There are various origins and fields of tradition; they can refer to:

- the forms of artistic heritage of a particular culture.

- beliefs or customs instituted and maintained by societies and governments, such as national anthems and national holidays, such as Federal holidays in the United States.

- beliefs or customs maintained by religious denominations and Church bodies that share history, customs, culture, and, to some extent, body of teachings. For example, one can speak of Islam's tradition or Christianity's tradition.

Many objects, beliefs and customs can be traditional. Rituals of social interaction can be traditional, with phrases and gestures such as saying "thank you", sending birth announcements, greeting cards, etc. Tradition can also refer to larger concepts practiced by groups (family traditions at Christmas), organizations (company's picnic) or societies, such as the practice of national and public holidays. Some of the oldest traditions include monotheism (three millennia) and citizenship (two millennia). It can also include material objects, such as buildings, works of art or tools.

Tradition is often used as an adjective, in contexts such as traditional music, traditional medicine, traditional values and others. In such constructions tradition refers to specific values and materials particular to the discussed context, passed through generations.

Invention of tradition

The term "invention of tradition", introduced by E. J. Hobsbawm, refers to situations when a new practice or object is introduced in a manner that implies a connection with the past that is not necessarily present. For example, the Panhellenic Games were a tradition in Ancient Greece where only Greek men from Greece and Greek colonies could compete. A tradition may be deliberately created and promulgated for personal, commercial, political, or national self-interest, as was done in colonial Africa; or it may be adopted rapidly based on a single highly publicized event, rather than developing and spreading organically in a population, as in the case of the white wedding dress, which only became popular after Queen Victoria wore a white gown at her wedding to Albert of Saxe-Coburg.

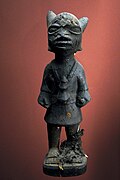

An example of an invention of tradition is the rebuilding of the Palace of Westminster (location of the British Parliament) in the Gothic style. Similarly, most of the traditions associated with monarchy of the United Kingdom, seen as rooted deep in history, actually date to 19th century. Other examples include the invention of tradition in Africa and other colonial holdings by the occupying forces. Requiring legitimacy, the colonial power would often invent a "tradition" which they could use to legitimize their own position. For example, a certain succession to a chiefdom might be recognized by a colonial power as traditional in order to favour their own candidates for the job. Often these inventions were based in some form of tradition, but were exaggerated, distorted, or biased toward a particular interpretation.

Invented traditions are a central component of modern national cultures, providing a commonality of experience and promoting the unified national identity espoused by nationalism. Common examples include public holidays (particularly those unique to a particular nation), the singing of national anthems, and traditional national cuisine (see national dish). Expatriate and immigrant communities may continue to practice the national traditions of their home nation.

In scholarly discourse

In science, tradition is often used in the literature in order to define the relationship of an author's thoughts to that of his or her field. In 1948, philosopher of science Karl Popper suggested that there should be a "rational theory of tradition" applied to science which was fundamentally sociological. For Popper, each scientist who embarks on a certain research trend inherits the tradition of the scientists before them as he or she inherits their studies and any conclusions that superseded it. Unlike myth, which is a means of explaining the natural world through means other than logical criticism, scientific tradition was inherited from Socrates, who proposed critical discussion, according to Popper. For Thomas Kuhn, who presented his thoughts in a paper presented in 1977, a sense of such a critical inheritance of tradition is, historically, what sets apart the best scientists who change their fields is an embracement of tradition.

Traditions are a subject of study in several academic fields in social sciences—chiefly anthropology, archaeology, and biology—with somewhat different meanings in different fields. It is also used in varying contexts in other fields, such as history, psychology and sociology. Social scientists and others have worked to refine the commonsense concept of tradition to make it into a useful concept for scholarly analysis. In the 1970s and 1980s, Edward Shils explored the concept in detail. Since then, a wide variety of social scientists have criticized traditional ideas about tradition; meanwhile, "tradition" has come into usage in biology as applied to nonhuman animals.

Tradition as a concept variously defined in different disciplines should not be confused with various traditions (perspectives, approaches) in those disciplines.

Anthropology

Tradition is one of the key concepts in anthropology; it can be said that anthropology is the study of "tradition in traditional societies". There is however no "theory of tradition", as for most anthropologists the need to discuss what tradition is seems unnecessary, as defining tradition is both unnecessary (everyone can be expected to know what it is) and unimportant (as small differences in definition would be just technical). There are however dissenting views; scholars such as Pascal Boyer argue that defining tradition and developing theories about it are important to the discipline.

Archaeology

In archaeology, the term tradition is a set of cultures or industries which appear to develop on from one another over a period of time. The term is especially common in the study of American archaeology.

Biology

Biologists, when examining groups of non-humans, have observed repeated behaviors which are taught within communities from one generation to the next. Tradition is defined in biology as "a behavioral practice that is relatively enduring (i.e., is performed repeatedly over a period of time), that is shared among two or more members of a group, that depends in part on socially aided learning for its generation in new practitioners", and has been called a precursor to "culture" in the anthropological sense.

Behavioral traditions have been observed in groups of fish, birds, and mammals. Groups of orangutans and chimpanzees, in particular, may display large numbers of behavioral traditions, and in chimpanzees, transfer of traditional behavior from one group to another (not just within a group) has been observed. Such behavioral traditions may have evolutionary significance, allowing adaptation at a faster rate than genetic change.

Musicology and ethnomusicology

In the field of musicology and ethnomusicology tradition refers to the belief systems, repertoire, techniques, style and culture that is passed down through subsequent generations. Tradition in music suggests a historical context with which one can perceive distinguishable patterns. Along with a sense of history, traditions have a fluidity that cause them to evolve and adapt over time. While both musicology and ethnomusicology are defined by being 'the scholarly study of music' they differ in their methodology and subject of research. 'Tradition, or traditions, can be presented as a context in which to study the work of a specific composer or as a part of a wide-ranging historical perspective.'

Sociology

The concept of tradition, in early sociological research (around the turn of the 19th and 20th century), referred to that of the traditional society, as contrasted by the more modern industrial society. This approach was most notably portrayed in Max Weber's concepts of traditional authority and modern rational-legal authority. In more modern works, One hundred years later, sociology sees tradition as a social construct used to contrast past with the present and as a form of rationality used to justify certain course of action.

Traditional society is characterized by lack of distinction between family and business, division of labor influenced primarily by age, gender, and status, high position of custom in the system of values, self-sufficiency, preference to saving and accumulation of capital instead of productive investment, relative autarky. Early theories positing the simple, unilineal evolution of societies from traditional to industrial model are now seen as too simplistic.

In 1981 Edward Shils in his book Tradition put forward a definition of tradition that became universally accepted. According to Shils, tradition is anything which is transmitted or handed down from the past to the present.

Another important sociological aspect of tradition is the one that relates to rationality. It is also related to the works of Max Weber (see theories of rationality), and were popularized and redefined in 1992 by Raymond Boudon in his book Action. In this context tradition refers to the mode of thinking and action justified as "it has always been that way". This line of reasoning forms the basis of the logical flaw of the appeal to tradition (or argumentum ad antiquitatem), which takes the form "this is right because we've always done it this way." In most cases such an appeal can be refuted on the grounds that the "tradition" being advocated may no longer be desirable, or, indeed, may never have been despite its previous popularity.

Philosophy

The idea of tradition is important in philosophy. Twentieth century philosophy is often divided between an 'analytic' tradition, dominant in Anglophone and Scandinavian countries, and a 'continental' tradition, dominant in German and Romance speaking Europe. Increasingly central to continental philosophy is the project of deconstructing what its proponents, following Martin Heidegger, call 'the tradition', which began with Plato and Aristotle. In contrast, some continental philosophers - most notably, Hans-Georg Gadamer - have attempted to rehabilitate the tradition of Aristotelianism. This move has been replicated within analytic philosophy by Alasdair MacIntyre. However, MacIntyre has himself deconstructed the idea of 'the tradition', instead posing Aristotelianism as one philosophical tradition in rivalry with others.

In political and religious discourse

The concepts of tradition and traditional values are frequently used in political and religious discourse to establish the legitimacy of a particular set of values. In the United States in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the concept of tradition has been used to argue for the centrality and legitimacy of conservative religious values. Similarly, strands of orthodox theological thought from a number of world religions openly identify themselves as wanting a return to tradition. For example, the term "traditionalist Catholic" refers to those, such as Archbishop Lefebvre, who want the worship and practices of the Church to be as they were before the Second Vatican Council of 1962–65. Likewise, Sunni Muslims are referred to as Ahl el-Sunnah wa Al-Jamā‘ah (Arabic: أهل السنة والجماعة), literally "people of the tradition [of Muhammad] and the community", emphasizing their attachment to religious and cultural tradition.

More generally, tradition has been used as a way of determining the political spectrum, with right-wing parties having a stronger affinity to certain ways of the past than left-wing ones. Here, the concept of adherence tradition is embodied by the political philosophy of traditionalist conservatism (or simply traditionalism), which emphasizes the need for the principles of natural law and transcendent moral order, hierarchy and organic unity, agrarianism, classicism and high culture, and the intersecting spheres of loyalty. Traditionalists would therefore reject the notions of individualism, liberalism, modernity, and social progress, but promote cultural and educational renewal, and revive interest in the Church, the family, the State and local community. This view has been criticised for including in its notion of tradition practices which are no longer considered to be desirable, for example, stereotypical views of the place of women in domestic affairs.

In other societies, especially ones experiencing rapid social change, the idea of what is "traditional" may be widely contested, with different groups striving to establish their own values as the legitimate traditional ones. Defining and enacting traditions in some cases can be a means of building unity between subgroups in a diverse society; in other cases, tradition is a means of othering and keeping groups distinct from one another.

In artistic discourse

In artistic contexts, in the performance of traditional genres (such as traditional dance), adherence to traditional guidelines is of greater importance than performer's preferences. It is often the unchanging form of certain arts that leads to their perception as traditional. For artistic endeavors, tradition has been used as a contrast to creativity, with traditional and folk art associated with unoriginal imitation or repetition, in contrast to fine art, which is valued for being original and unique. More recent philosophy of art, however, considers interaction with tradition as integral to the development of new artistic expression.

Relationship to other concepts

In the social sciences, tradition is often contrasted with modernity, particularly in terms of whole societies. This dichotomy is generally associated with a linear model of social change, in which societies progress from being traditional to being modern. Tradition-oriented societies have been characterized as valuing filial piety, harmony and group welfare, stability, and interdependence, while a society exhibiting modernity would value "individualism (with free will and choice), mobility, and progress." Another author discussing tradition in relationship to modernity, Anthony Giddens, sees tradition as something bound to ritual, where ritual guarantees the continuation of tradition. Gusfield and others, though, criticize this dichotomy as oversimplified, arguing that tradition is dynamic, heterogeneous, and coexists successfully with modernity even within individuals.

Tradition should be differentiated from customs, conventions, laws, norms, routines, rules and similar concepts. Whereas tradition is supposed to be invariable, they are seen as more flexible and subject to innovation and change. Whereas justification for tradition is ideological, the justification for other similar concepts is more practical or technical. Over time, customs, routines, conventions, rules and such can evolve into traditions, but that usually requires that they stop having (primarily) a practical purpose. For example, wigs worn by lawyers were at first common and fashionable; spurs worn by military officials were at first practical but now are both impractical and traditional.

Preservation

The legal protection of tradition includes a number of international agreements and national laws. In addition to the fundamental protection of cultural property, there is also cooperation between the United Nations, UNESCO and Blue Shield International in the protection or recording of traditions and customs. The protection of culture and traditions is becoming increasingly important nationally and internationally.

In many countries, concerted attempts are being made to preserve traditions that are at risk of being lost. A number of factors can exacerbate the loss of tradition, including industrialization, globalization, and the assimilation or marginalization of specific cultural groups. Customary celebrations and lifestyles are among the traditions that are sought to be preserved. Likewise, the concept of tradition has been used to defend the preservation and reintroduction of minority languages such as Cornish under the auspices of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. Specifically, the charter holds that these languages "contribute to the maintenance and development of Europe's cultural wealth and traditions". The Charter goes on to call for "the use or adoption... of traditional and correct forms of place-names in regional or minority languages". Similarly, UNESCO includes both "oral tradition" and "traditional manifestations" in its definition of a country's cultural properties and heritage. It therefore works to preserve tradition in countries such as Brazil.

In Japan, certain artworks, structures, craft techniques and performing arts are considered by the Japanese government to be a precious legacy of the Japanese people, and are protected under the Japanese Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties. This law also identifies people skilled at traditional arts as "National Living Treasures", and encourages the preservation of their craft.

For native peoples like the Māori in New Zealand, there is conflict between the fluid identity assumed as part of modern society and the traditional identity with the obligations that accompany it; the loss of language heightens the feeling of isolation and damages the ability to perpetuate tradition.

Traditional cultural expressions

The phrase "traditional cultural expressions" is used by the World Intellectual Property Organization to refer to "any form of artistic and literary expression in which traditional culture and knowledge are embodied. They are transmitted from one generation to the next, and include handmade textiles, paintings, stories, legends, ceremonies, music, songs, rhythms and dance."