From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(Percent change from a year earlier)

Core CPI

The monetary policy of The United States is the set of policies related to the minting and printing of United States dollars, plus the legal exchange of currency, demand deposits, the money supply, etc. In the United States, the central bank, The Federal Reserve System, colloquially known as "The Fed" is the monetary authority.

It is significant to point out that the United States uses a fiat currency as of 1933, whereas from 1873 - 1933 a precious metal standard or gold standard was in use.

The Federal Reserve's board of governors, along with the Open Market Committee

are the principle arbiters of monetary policy in the United States,

though the U.S. is unique in that the monetary policy role is ultimately

shared along with the United States Treasury (US Treasury Securities). The Treasury is the penultimate agency on fiscal policy, though it is directly involved in monetary policy through printing & minting federal reserve notes and treasurys.

The Fed is largely concerned with policies related to the issuance of loans (including reserve rate and interest rates), along with other policies that determine the size and rate of growth of the money supply

(such as buying and selling government bonds), whereas the Treasury

deals directly with minting and printing as well as budgeting the

government. The U.S. Congress established three key objectives for monetary policy in the Federal Reserve Act: maximizing employment, stabilizing prices, and moderating long-term interest rates.

Overview

The Federal Reserve Act created the Federal Reserve System in 1913 as the central bank of the United States. Its primary task is to "conduct the nation's monetary policy

to promote maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term

interest rates in the U.S. economy". It is also tasked to promote the

stability of the financial system and regulate financial institutions,

and to act as lender of last resort.

The monetary policy of the United States is conducted by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), which is composed of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors and 5 out of the 12 Federal Reserve Bank presidents, and is implemented by all twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks.

Monetary policy refers to actions made by central banks which determine the size and growth rate of the money supply

available in the economy, and which would result in desired objectives

like low inflation, low unemployment and stable financial systems. The

economy's aggregate money supply is the total of

- M0 money, or Monetary Base - "dollars" in currency and bank money balances credited to the central bank's depositors, which are backed by the central bank's assets,

- plus M1, M2, M3 money - "dollars" in the form of bank money balances credited to banks' depositors, which are backed by the bank's assets and investments.

The FOMC influences the level of money available to the economy by the following means:

- Reserve requirements - specifies a required minimum percentage of deposits in a commercial bank

that should be held as reserve (i.e. as deposits with the Federal

Reserve), with the rest available to loan or invest. Higher requirements

mean less money loaned or invested, helping keep inflation in check.

Raising the federal funds rate earned on those reserves also helps achieve this objective.

- Open market operations - the Federal Reserve buys or sells US Treasury bonds

and other securities held by banks in exchange for reserves; more

reserves increase a bank's capacity to loan or invest elsewhere.

- Discount window lending - banks can borrow from the Federal Reserve.

Monetary policy

directly affects interest rates; it indirectly affects stock prices,

wealth, and currency exchange rates. Through these channels, monetary

policy influences spending, investment, production, employment, and

inflation in the United States. Effective monetary policy complements fiscal policy to support economic growth.

The Federal Reserve's monetary policy objectives to keep prices stable and unemployment low is often called the dual mandate. This replaces past practices under a gold standard

where the main concern is the gold equivalent of the local currency, or

under a gold exchange standard where the concern is fixing the exchange

rate versus another gold-convertible currency (previously practiced

worldwide under the Bretton Woods Agreement of 1944 via fixed exchange rates to the U.S. dollar).

Money supply

Yearly M2 money supply increases

Monthly M2 money supply increases

Monthly M2 money supply decreases

United States money supply

M2

M1

The money supply has different components, generally broken down into

"narrow" and "broad" money, reflecting the different degrees of

liquidity ('spendability') of each different type, as broader forms of

money can be converted into narrow forms of money (or may be readily

accepted as money by others, such as personal checks).

For example, demand deposits

are technically promises to pay on demand, while savings deposits are

promises to pay subject to some withdrawal restrictions, and

Certificates of Deposit are promises to pay only at certain specified

dates; each can be converted into money, but "narrow" forms of money can

be converted more readily. The Federal Reserve directly controls only

the most narrow form of money, physical cash outstanding along with the

reserves of banks throughout the country (known as M0 or the monetary

base); the Federal Reserve indirectly influences the supply of other types of money.

Broad money includes money held in deposit balances in banks and

other forms created in the financial system. Basic economics also

teaches that the money supply shrinks when loans are repaid; however, the money supply will not necessarily decrease depending on

the creation of new loans and other effects. Other than loans,

investment activities of commercial banks and the Federal Reserve also

increase and decrease the money supply.

Discussion of "money" often confuses the different measures and may

lead to misguided commentary on monetary policy and misunderstandings of

policy discussions.

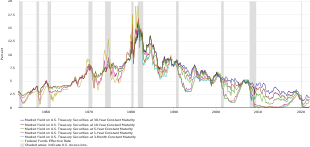

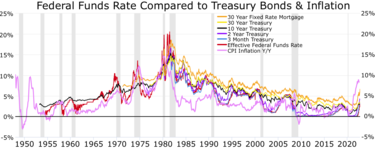

Inverted yield curves to tame inflation

The Federal Reserve has used the Federal funds rate as a primary tool to bring down inflation (quantitative tightening) or induce more inflation (quantitative easing) to get to their target of 2% annual inflation.

To tame inflation the Fed raises the FFR causing shorter term interest

rates to rise and eventually climb above their longer maturity bonds causing an Inverted yield curve which usually predates a recession by several months which is deflationary.

Current state of US monetary policy

In August 2020, after undershooting its 2% inflation target for

years, the Fed announced it would be allowing inflation to temporarily

rise higher, in order to target an average of 2% over the longer term. It is still unclear if this change will make much practical difference in monetary policy anytime soon.

Structure of modern US institutions

Federal Reserve

Monetary policy in the US is determined and implemented by the US Federal Reserve System, commonly referred to as the Federal Reserve. Established in 1913 by the Federal Reserve Act to provide central banking functions,

the Federal Reserve System is a quasi-public institution. Ostensibly,

the Federal Reserve Banks are 12 private banking corporations;

they are independent in their day-to-day operations, but legislatively

accountable to Congress through the auspices of Federal Reserve Board of Governors.

The Board of Governors is an independent governmental agency

consisting of seven officials and their support staff of over 1800

employees headquartered in Washington, D.C.

It is independent in the sense that the Board currently operates

without official obligation to accept the requests or advice of any

elected official with regard to actions on the money supply, and its methods of funding also preserve independence. The Governors are nominated by the President of the United States, and nominations must be confirmed by the U.S. Senate. There is very strong economic consensus that independence from political influence is good for monetary policy.

The presidents of the Federal Reserve Banks are nominated by each

bank's respective Board of Directors, but must also be approved by the

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve. The Chairman of the Federal

Reserve Board is generally considered to have the most important

position, followed by the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New

York.

The Federal Reserve System is primarily funded by interest collected on

their portfolio of securities from the US Treasury, and the Fed has

broad discretion in drafting its own budget, but, historically, nearly all the interest the Federal Reserve collects is rebated to the government each year.

The Federal Reserve has four main mechanisms for manipulating the money supply. It can buy or sell treasury securities. Selling securities has the effect of reducing the monetary base

(because it accepts money in return for purchase of securities), taking

that money out of circulation. Purchasing treasury securities increases

the monetary base (because it pays out hard currency in exchange for accepting securities). Secondly, the discount rate can be changed. Third, the Federal Reserve can adjust the reserve requirement, which can affect the money multiplier; the reserve requirement is adjusted only infrequently, and was last adjusted in March 2020, at which time it was set to zero. At a reserve requirement of zero, the money multiplier is undefined, because calculating it would involve division by zero.

In October 2008 the Federal Reserve added a fourth mechanism by

beginning to pay interest on reserves, which one year later the Fed

Chairman described as the "most important tool" the Fed could use to

raise interest rates.

In practice, the Federal Reserve uses open market operations to influence short-term interest rates, which is the primary tool of monetary policy. The federal funds rate, for which the Federal Open Market Committee

announces a target on a regular basis, reflects one of the key rates

for interbank lending. Open market operations change the supply of

reserve balances, and the federal funds rate is sensitive to these

operations.

In theory, the Federal Reserve has unlimited capacity to

influence this rate, and although the federal funds rate is set by banks

borrowing and lending funds to each other, the federal funds rate

generally stays within a limited range above and below the target (as

participants are aware of the Fed's power to influence this rate).

Assuming a closed economy, where foreign capital or trade

does not affect the money supply, when money supply increases, interest

rates go down. Businesses and consumers have a lower cost of capital

and can increase spending and capital improvement projects. This

encourages short-term growth. Conversely, when the money supply falls,

interest rates go up, increasing the cost of capital and leading to more

conservative spending and investment. The Federal reserve increases

interest rates to combat Inflation.

U.S. Treasury

10 Year Treasury Bond

2 Year Treasury Bond

3 month Treasury Bond

Effective Federal Funds Rate

Recessions

A United States Treasury security is an IOU from the US Government. It is a government debt instrument issued by the United States Department of the Treasury to finance government spending as an alternative to taxation. Treasury securities are often referred to simply as "Treasuries". Since 2012 the management of government debt has been arranged by the Bureau of the Fiscal Service, succeeding the Bureau of the Public Debt.

Private commercial banks

When money is deposited in a bank, it can then be lent out to another

person. If the initial deposit was $100 and the bank lends out $100 to

another customer the money supply has increased by $100. However,

because the depositor can ask for the money back, banks have to maintain

minimum reserves to service customer needs. If the reserve requirement

is 10% then, in the earlier example, the bank can lend $90 and thus the

money supply increases by only $90. The reserve requirement therefore

acts as a limit on this multiplier effect. Because the reserve

requirement only applies to the more narrow forms of money creation

(corresponding to M1), but does not apply to certain types of deposits

(such as time deposits), reserve requirements play a limited role in monetary policy.

Money creation

As on Nov 2021 the US government maintains over US$2214.3 billion in

cash money (primarily Federal Reserve Notes) in circulation throughout

the world,

up from a sum of less than $30 billion in 1959. Below is an outline of

the process which is currently used to control the amount of money in

the economy. The amount of money in circulation generally increases to

accommodate money demanded by the growth of the country's production. The process of money creation usually goes as follows:

- Banks go through their daily transactions. Of the total money

deposited at banks, significant and predictable proportions often remain

deposited, and may be referred to as "core deposits". Banks use the

bulk of "non-moving" money (their stable or "core" deposit base) by

loaning it out. Banks have a legal obligation to keep a certain fraction of bank deposit money on-hand at all times.

- In order to raise additional money to cover excess spending, Congress increases the size of the National Debt by issuing securities typically in the form of a Treasury Bond (see United States Treasury security).

It offers the Treasury security for sale, and someone pays cash to the

government in exchange. Banks are often the purchasers of these

securities, and these securities currently play a crucial role in the

process.

- The 12-person Federal Open Market Committee,

which consists of the heads of the Federal Reserve System (the seven

Federal governors and five bank presidents), meets eight times a year to

determine how they would like to influence the economy. They create a plan called the country's "monetary policy" which sets targets for things such as interest rates.

- Every business day, the Federal Reserve System engages in Open market operations.

If the Federal Reserve wants to increase the money supply, it will buy

securities (such as U.S. Treasury Bonds) anonymously from banks in

exchange for dollars. If the Federal Reserve wants to decrease the money

supply, it will sell securities to the banks in exchange for dollars,

taking those dollars out of circulation.

When the Federal Reserve makes a purchase, it credits the seller's

reserve account (with the Federal Reserve). The money that it deposits

into the seller's account is not transferred from any existing funds,

therefore it is at this point that the Federal Reserve has created High-powered money.

- By means of open market operations, the Federal Reserve affects the free reserves of commercial banks in the country.

Anna Schwartz explains that "if the Federal Reserve increases reserves,

a single bank can make loans up to the amount of its excess reserves,

creating an equal amount of deposits".

- Since banks have more free reserves, they may loan out the money,

because holding the money would amount to accepting the cost of foregone

interest. When a loan is granted, a person is generally granted the money by adding to the balance on their bank account.

- This is how the Federal Reserve's high-powered money is multiplied

into a larger amount of broad money, through bank loans; as written in a

particular case study, "as banks increase or decrease loans, the

nation's (broad) money supply increases or decreases."

Once granted these additional funds, the recipient has the option to

withdraw physical currency (dollar bills and coins) from the bank, which

will reduce the amount of money available for further on-lending (and

money creation) in the banking system.

- In many cases, account-holders will request cash withdrawals, so

banks must keep a supply of cash handy. When they believe they need

more cash than they have on hand, banks can make requests for cash with

the Federal Reserve. In turn, the Federal Reserve examines these

requests and places an order for printed money with the US Treasury

Department. The Treasury Department sends these requests to the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (to make dollar bills) and the Bureau of the Mint (to stamp the coins).

- The U.S. Treasury sells this newly printed money to the Federal Reserve for the cost of printing. This is about 6 cents per bill for any denomination.

Aside from printing costs, the Federal Reserve must pledge collateral

(typically government securities such as Treasury bonds) to put new

money, which does not replace old notes, into circulation. This printed cash can then be distributed to banks, as needed.

Though the Federal Reserve authorizes and distributes the currency

printed by the Treasury (the primary component of the narrow monetary

base), the broad money supply is primarily created by commercial banks

through the money multiplier mechanism. One textbook summarizes the process as follows:

"The Fed" controls the money supply in the United States

by controlling the amount of loans made by commercial banks. New loans

are usually in the form of increased checking account balances, and

since checkable deposits are part of the money supply, the money supply

increases when new loans are made ...

This type of money is convertible into cash when depositors request

cash withdrawals, which will require banks to limit or reduce their

lending. The vast majority of the broad money supply throughout the world represents current outstanding loans of banks to various debtors. A very small amount of U.S. currency still exists as "United States Notes",

which have no meaningful economic difference from Federal Reserve notes

in their usage, although they departed significantly in their method of

issuance into circulation. The currency distributed by the Federal

Reserve has been given the official designation of "Federal Reserve Notes".

Significant effects

In 2005, the Federal Reserve held approximately 9% of the national debt

as assets against the liability of printed money. In previous periods,

the Federal Reserve has used other debt instruments, such as debt

securities issued by private corporations. During periods when the

national debt of the United States has declined significantly (such as

happened in fiscal years 1999 and 2000), monetary policy and financial

markets experts have studied the practical implications of having "too

little" government debt: both the Federal Reserve and financial markets

use the price information, yield curve and the so-called risk free rate extensively.

Experts are hopeful that other assets could take the place of

National Debt as the base asset to back Federal Reserve notes, and Alan Greenspan,

long the head of the Federal Reserve, has been quoted as saying, "I am

confident that U.S. financial markets, which are the most innovative and

efficient in the world, can readily adapt to a paydown of Treasury debt

by creating private alternatives with many of the attributes that

market participants value in Treasury securities."

In principle, the government could still issue debt securities in

significant quantities while having no net debt, and significant

quantities of government debt securities are also held by other

government agencies.

Although the U.S. government receives income overall from seigniorage, there are costs associated with maintaining the money supply. Leading ecological economist and steady-state theorist Herman Daly,

claims that "over 95% of our [broad] money supply [in the United

States] is created by the private banking system (demand deposits) and

bears interest as a condition of its existence",

a conclusion drawn from the Federal Reserve's ultimate dependence on

increased activity in fractional reserve lending when it exercises open

market operations.

Economist Eric Miller criticizes Daly's logic because money is created

in the banking system in response to demand for the money, which justifies cost.

Thus, use of expansionary open market operations typically

generates more debt in the private sector of society (in the form of

additional bank deposits). The private banking system charges interest to borrowers as a cost to borrow the money. The interest costs are borne by those that have borrowed, and without this borrowing, open market operations would be unsuccessful in maintaining the broad money supply,

though alternative implementations of monetary policy could be used.

Depositors of funds in the banking system are paid interest on their

savings (or provided other services, such as checking account privileges

or physical security for their "cash"), as compensation for "lending"

their funds to the bank.

Increases (or contractions) of the money supply corresponds to growth (or contraction) in interest-bearing debt in the country.

The concepts involved in monetary policy may be widely misunderstood in

the general public, as evidenced by the volume of literature on topics

such as "Federal Reserve conspiracy" and "Federal Reserve fraud".

Uncertainties

A few of the uncertainties involved in monetary policy decision making are described by the federal reserve:

- While these policy choices seem reasonably straightforward,

monetary policy makers routinely face certain notable uncertainties.

First, the actual position of the economy and growth in aggregate demand

at any time are only partially known, as key information on spending,

production, and prices becomes available only with a lag. Therefore,

policy makers must rely on estimates of these economic variables when

assessing the appropriate course of policy, aware that they could act on

the basis of misleading information. Second, exactly how a given

adjustment in the federal funds rate will affect growth in aggregate

demand—in terms of both the overall magnitude and the timing of its

impact—is never certain. Economic models can provide rules of thumb for

how the economy will respond, but these rules of thumb are subject to

statistical error. Third, the growth in aggregate supply, often called

the growth in potential output, cannot be measured with certainty.

- In practice, as previously noted, monetary policy makers do not have

up-to-the-minute information on the state of the economy and prices.

Useful information is limited not only by lags in the collection and

availability of key data but also by later revisions, which can alter

the picture considerably. Therefore, although monetary policy makers

will eventually be able to offset the effects that adverse demand shocks

have on the economy, it will be some time before the shock is fully

recognized and—given the lag between a policy action and the effect of

the action on aggregate demand—an even longer time before it is

countered. Add to this the uncertainty about how the economy will

respond to an easing or tightening of policy of a given magnitude, and

it is not hard to see how the economy and prices can depart from a

desired path for a period of time.

- The statutory goals of maximum employment and stable prices are

easier to achieve if the public understands those goals and believes

that the Federal Reserve will take effective measures to achieve them.

- Although the goals of monetary policy are clearly spelled out in

law, the means to achieve those goals are not. Changes in the FOMC's

target federal funds rate take some time to affect the economy and

prices, and it is often far from obvious whether a selected level of the

federal funds rate will achieve those goals.

Opinions of the Federal Reserve

The

Federal Reserve is lauded by some economists, while being the target of

scathing criticism by other economists, legislators, and sometimes

members of the general public. The former Chairman of the Federal

Reserve Board, Ben Bernanke, is one of the leading academic critics of the Federal Reserve's policies during the Great Depression.

Achievements

One

of the functions of a central bank is to facilitate the transfer of

funds through the economy, and the Federal Reserve System is largely

responsible for the efficiency in the banking sector. There have also

been specific instances which put the Federal Reserve in the spotlight

of public attention. For instance, after the stock market crash in

1987, the actions of the Fed are generally believed to have aided in

recovery. Also, the Federal Reserve is credited for easing tensions in

the business sector with the reassurances given following the 9/11

terrorist attacks on the United States.

Criticisms

The Federal Reserve has been the target of various criticisms, involving: accountability, effectiveness, opacity, inadequate banking regulation, and potential market distortion.

Federal Reserve policy has also been criticized for directly and

indirectly benefiting large banks instead of consumers. For example,

regarding the Federal Reserve's response to the 2007–2010 financial

crisis, Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz explained how the U.S. Federal Reserve was implementing another monetary policy—creating currency—as a method to combat the liquidity trap.

By creating $600 billion and inserting this directly into banks

the Federal Reserve intended to spur banks to finance more domestic

loans and refinance mortgages. However, banks instead were spending the

money in more profitable areas by investing internationally in emerging

markets. Banks were also investing in foreign currencies which Stiglitz

and others point out may lead to currency wars while China redirects its currency holdings away from the United States.

Auditing

The

Federal Reserve is subject to different requirements for transparency

and audits than other government agencies, which its supporters claim is

another element of the Fed's independence. Although the Federal Reserve

has been required by law to publish independently audited financial statements

since 1999, the Federal Reserve is not audited in the same way as other

government agencies. Some confusion can arise because there are many

types of audits, including: investigative or fraud audits; and financial

audits, which are audits of accounting statements; there are also

compliance, operational, and information system audits.

The Federal Reserve's annual financial statements are audited by

an outside auditor. Similar to other government agencies, the Federal

Reserve maintains an Office of the Inspector General, whose mandate

includes conducting and supervising "independent and objective audits,

investigations, inspections, evaluations, and other reviews of Board

programs and operations". The Inspector General's audits and reviews are available on the Federal Reserve's website.

The Government Accountability Office

(GAO) has the power to conduct audits, subject to certain areas of

operations that are excluded from GAO audits; other areas may be audited

at specific Congressional request, and have included bank supervision,

government securities activities, and payment system activities. The GAO is specifically restricted any authority over monetary policy transactions;

the New York Times reported in 1989 that "such transactions are now

shielded from outside audit, although the Fed influences interest rates

through the purchase of hundreds of billions of dollars in Treasury

securities."

As mentioned above, it was in 1999 that the law governing the Federal

Reserve was amended to formalize the already-existing annual practice of

ordering independent audits of financial statements for the Federal

Reserve Banks and the Board; the GAO's restrictions on auditing monetary policy continued, however.

Congressional oversight on monetary policy operations, foreign transactions, and the

FOMC operations is exercised through the requirement for reports and through semi-annual monetary policy hearings.

Scholars have conceded that the hearings did not prove an effective

means of increasing oversight of the Federal Reserve, perhaps because

"Congresspersons prefer to bash an autonomous and secretive Fed for

economic misfortune rather than to share the responsibility for that

misfortune with a fully accountable Central Bank", although the Federal

Reserve has also consistently lobbied to maintain its independence and

freedom of operation.

Fulfillment of wider economic goals

By law, the goals of the Fed's monetary policy are: high employment, sustainable growth, and stable prices.

Critics say that monetary policy in the United States has not

achieved consistent success in meeting the goals that have been

delegated to the Federal Reserve System by Congress. Congress began to

review more options with regard to macroeconomic influence beginning in

1946 (after World War II), with the Federal Reserve receiving specific

mandates in 1977 (after the country suffered a period of stagflation).

Throughout the period of the Federal Reserve following the

mandates, the relative weight given to each of these goals has changed,

depending on political developments. In particular, the theories of Keynesianism and monetarism

have had great influence on both the theory and implementation of

monetary policy, and the "prevailing wisdom" or consensus view of the

economic and financial communities has changed over the years.

- Elastic currency (magnitude of the money multiplier): the

success of monetary policy is dependent on the ability to strongly

influence the supply of money available to the citizens. If a currency

is highly "elastic" (that is, has a higher money multiplier,

corresponding to a tendency of the financial system to create more broad

money for a given quantity of base money), plans to expand the money

supply and accommodate growth are easier to implement. Low elasticity

was one of many factors that contributed to the depth of the Great Depression:

as banks cut lending, the money multiplier fell, and at the same time

the Federal Reserve constricted the monetary base. The depression of

the late 1920s is generally regarded as being the worst in the country's

history, and the Federal Reserve has been criticized for monetary

policy which worsened the depression.

Partly to alleviate problems related to the depression, the United

States transitioned from a gold standard and now uses a fiat currency;

elasticity is believed to have been increased greatly.

The value of $1 over time, in 1776 dollars.

- Stable prices – While some economists would regard any consistent inflation as a sign of unstable prices, policymakers could be satisfied with 1 or 2%;

the consensus of "price stability" constituting long-run inflation of

1–2% is, however, a relatively recent development, and a change that has

occurred at other central banks throughout the world. Inflation has

averaged a 4.2% increase annually following the mandates applied

in 1977; historic inflation since the establishment of the Federal

Reserve in 1913 has averaged 3.4%. In contrast, some research indicates that average inflation

for the 250 years before the system was near zero percent, though there

were likely sharper upward and downward spikes in that timeframe as

compared with more recent times. Central banks in some other countries, notably the German Bundesbank, had considerably better records of achieving price stability drawing on experience from the two episodes of hyperinflation and economic collapse under the country's previous central bank.

Inflation worldwide has fallen significantly since former

Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker began his tenure in 1979, a

period which has been called the Great Moderation; some commentators

attribute this to improved monetary policy worldwide, particularly in

the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. BusinessWeek notes that inflation has been relatively low since mid-1980s

and it was during this time that Volcker wrote (in 1995), "It is a

sobering fact that the prominence of central banks [such as the Federal

Reserve] in this century has coincided with a general tendency towards

more inflation, not less. By and large, if the overriding objective is

price stability, we did better with the nineteenth-century gold standard

and passive central banks, with currency boards, or even with 'free

banking.'."

- Sustainable growth – The growth of the economy may not be sustainable as the ability for households to save money has been on an overall decline and household debt is consistently rising.

Causes of The Great Depression

Monetarists

believe that the Great Depression started as an ordinary recession, but

that significant policy mistakes by monetary authorities (especially

the Federal Reserve)

caused a shrinking of the money supply, which greatly exacerbated the

economic situation, causing a recession to descend into the Great

Depression.

Public confusion

The

Federal Reserve has established a library of information on their

websites, however, many experts have spoken about the general level of

public confusion that still exists on the subject of the economy; this

lack of understanding of macroeconomic questions and monetary policy,

however, exists in other countries as well. Critics of the Fed widely

regard the system as being "opaque", and one of the Fed's most vehement opponents of his time, Congressman Louis T. McFadden, even went so far as to say that "Every effort has been made by the Federal Reserve Board to conceal its powers. ... "

There are, on the other hand, many economists who support the

need for an independent central banking authority, and some have

established websites that aim to clear up confusion about the economy

and the Federal Reserve's operations. The Federal Reserve website

itself publishes various information and instructional materials for a

variety of audiences.

Criticism of government interference

Some economists, especially those belonging to the heterodox Austrian School, criticize the idea of even establishing monetary policy, believing that it distorts investment. Friedrich Hayek won the Nobel Prize for his elaboration of the Austrian business cycle theory.

Briefly, the theory holds that an artificial injection of credit,

from a source such as a central bank like the Federal Reserve, sends

false signals to entrepreneurs to engage in long-term investments due to

a favorably low interest rate. However, the surge of investments

undertaken represents an artificial boom, or bubble, because the low

interest rate was achieved by an artificial expansion of the money

supply and not by savings. Hence, the pool of real savings and resources

have not increased and do not justify the investments undertaken.

These investments, which are more appropriately called

"malinvestments", are realized to be unsustainable when the artificial

credit spigot is shut off and interest rates rise. The malinvestments

and unsustainable projects are liquidated, which is the recession. The

theory demonstrates that the problem is the artificial boom which causes

the malinvestments in the first place, made possible by an artificial

injection of credit not from savings.

According to Austrian economics, without government intervention,

interest rates will always be an equilibrium between the

time-preferences of borrowers and savers, and this equilibrium is simply

distorted by government intervention. This distortion, in their view,

is the cause of the business cycle. Some Austrian economists—but by no means all—also support full reserve banking, a hypothetical financial/banking system where banks may not lend deposits. Others may advocate free banking,

whereby the government abstains from any interference in what

individuals may choose to use as money or the extent to which banks

create money through the deposit and lending cycle.

Reserve requirement

The

Federal Reserve regulates banking, and one regulation under its direct

control is the reserve requirement which dictates how much money banks

must keep in reserves, as compared to its demand deposits. Banks use

their observation that the majority of deposits are not requested by the

account holders at the same time.

Until March 2020 the Federal Reserve required that banks keep 10%

of their deposits on hand, but in March 2020 the reserve requirement

was reduced to zero. Some countries have no nationally mandated reserve requirements—banks

use their own resources to determine what to hold in reserve, however

their lending is typically constrained by other regulations. Other factors being equal, lower reserve percentages increases the possibility of Bank runs, such as the widespread runs of 1931.

Low reserve requirements also allow for larger expansions of the money

supply by actions of commercial banks—currently the private banking

system has created much of the broad money supply of US dollars through

lending activity.

Monetary policy reform calling for 100% reserves has been advocated by economists such as: Irving Fisher, Frank Knight, many ecological economists along with economists of the Chicago School and Austrian School. Despite calls for reform, the nearly universal practice of fractional-reserve banking has remained in the United States.

Criticism of private sector involvement

Historically and to the present day, various social and political movements (such as social credit)

have criticized the involvement of the private sector in "creating

money", claiming that only the government should have the power to "make

money". Some proponents also support full reserve banking or other

non-orthodox approaches to monetary policy. Various terminology may be

used, including "debt money", which may have emotive or political

connotations. These are generally considered to be akin to conspiracy

theories by mainstream economists and ignored in academic literature on

monetary policy.