From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The evolutionary emergence of language in the

human species

has been a subject of speculation for several centuries. The topic is

difficult to study because of the lack of direct evidence. Consequently,

scholars wishing to study the origins of language must draw inferences

from other kinds of evidence such as the

fossil record, archaeological evidence, contemporary language diversity, studies of

language acquisition, and comparisons between human

language and systems of communication existing

among animals (particularly

other primates). Many argue that the origins of language probably relate closely to the origins of

modern human behavior, but there is little agreement about the implications and directionality of this connection.

This shortage of

empirical evidence has led many scholars to regard the entire topic as unsuitable for serious study. In 1866, the

Linguistic Society of Paris

banned any existing or future debates on the subject, a prohibition

which remained influential across much of the western world until late

in the twentieth century.

[1] Today, there are various hypotheses about how, why, when, and where language might have emerged.

[2] Despite this, there is scarcely more agreement today than a hundred years ago, when

Charles Darwin's

theory of evolution by

natural selection provoked a rash of armchair speculation on the topic.

[3] Since the early 1990s, however, a number of

linguists,

archaeologists,

psychologists,

anthropologists, and others have attempted to address with new methods what some consider one of the hardest problems in science.

[4]

Approaches

One can sub-divide approaches to the origin of language according to some underlying assumptions:

[5]

- "Continuity theories" build on the idea that language exhibits so

much complexity that one cannot imagine it simply appearing from nothing

in its final form; therefore it must have evolved from earlier

pre-linguistic systems among our primate ancestors.

- "Discontinuity theories" take the opposite approach—that language,

as a unique trait which cannot be compared to anything found among

non-humans, must have appeared fairly suddenly during the course of human evolution.

- Some theories see language mostly as an innate faculty—largely genetically encoded.

- Other theories regard language as a mainly cultural system—learned through social interaction.

Noam Chomsky,

a prominent proponent of discontinuity theory, argues that a single

chance mutation occurred in one individual in the order of 100,000 years

ago, installing the language faculty (a component of the

mind–brain) in "perfect" or "near-perfect" form.

[6] A majority of linguistic scholars as of 2018

hold continuity-based theories, but they vary in how they envision

language development. Among those who see language as mostly innate,

some—notably

Steven Pinker[7]—avoid

speculating about specific precursors in nonhuman primates, stressing

simply that the language faculty must have evolved in the usual gradual

way.

[8] Others in this intellectual camp—notably Ib Ulbæk

[5]—hold that language evolved not from primate communication but from primate cognition, which is significantly more complex.

Those who see language as a socially learned tool of communication, such as

Michael Tomasello,

see it developing from the cognitively controlled aspects of primate

communication, these being mostly gestural as opposed to vocal.

[9][10] Where vocal precursors are concerned, many continuity theorists envisage language evolving from early human capacities for

song.

[11][12][13][14]

[15]

Transcending the continuity-versus-discontinuity divide, some

scholars view the emergence of language as the consequence of some kind

of social transformation

[16]

that, by generating unprecedented levels of public trust, liberated a

genetic potential for linguistic creativity that had previously lain

dormant.

[17][18][19] "Ritual/speech coevolution theory" exemplifies this approach.

[20][21] Scholars in this intellectual camp point to the fact that even

chimpanzees and

bonobos have latent symbolic capacities that they rarely—if ever—use in the wild.

[22]

Objecting to the sudden mutation idea, these authors argue that even if

a chance mutation were to install a language organ in an evolving

bipedal primate, it would be adaptively useless under all known primate

social conditions. A very specific social structure—one capable of

upholding unusually high levels of public accountability and trust—must

have evolved before or concurrently with language to make reliance on

"cheap signals" (words) an

evolutionarily stable strategy.

Because the

emergence of language lies so far back in

human prehistory,

the relevant developments have left no direct historical traces;

neither can comparable processes be observed today. Despite this, the

emergence of new sign languages in modern times—

Nicaraguan Sign Language, for example—may potentially offer insights into the developmental stages and creative processes necessarily involved.

[23] Another approach inspects early human fossils, looking for traces of physical adaptation to language use.

[24][25] In some cases, when the

DNA of extinct humans can be recovered, the presence or absence of genes considered to be language-relevant —

FOXP2, for example—may prove informative.

[26] Another approach, this time

archaeological, involves invoking

symbolic behavior (such as repeated ritual activity) that may leave an archaeological trace—such as mining and modifying ochre pigments for

body-painting—while developing theoretical arguments to justify inferences from

symbolism in general to language in particular.

[27][28][29]

The time range for the evolution of language and/or its anatomical

prerequisites extends, at least in principle, from the phylogenetic

divergence of

Homo (2.3 to 2.4 million years ago) from

Pan (5 to 6 million years ago) to the emergence of full

behavioral modernity some 150,000 – 50,000 years ago. Few dispute that

Australopithecus probably lacked vocal communication significantly more sophisticated than that of

great apes in general,

[30] but scholarly opinions vary as to the developments since the appearance of

Homo some 2.5 million years ago. Some scholars assume the development of primitive language-like systems (

proto-language) as early as

Homo habilis, while others place the development of

symbolic communication only with

Homo erectus (1.8 million years ago) or with

Homo heidelbergensis (0.6 million years ago) and the development of language proper with

Homo sapiens, currently estimated at less than 200,000 years ago.

Using statistical methods to estimate the time required to achieve the current spread and diversity in modern languages,

Johanna Nichols—a linguist at the

University of California, Berkeley—argued in 1998 that vocal languages must have begun diversifying in our species at least 100,000 years ago.

[31] A further study by Q. D. Atkinson

[12]

suggests that successive population bottlenecks occurred as our African

ancestors migrated to other areas, leading to a decrease in genetic and

phenotypic diversity. Atkinson argues that these bottlenecks also

affected culture and language, suggesting that the further away a

particular language is from Africa, the fewer

phonemes

it contains. By way of evidence, Atkinson claims that today's African

languages tend to have relatively large numbers of phonemes, whereas

languages from areas in

Oceania

(the last place to which humans migrated), have relatively few. Relying

heavily on Atkinson's work, a subsequent study has explored the rate at

which phonemes develop naturally, comparing this rate to some of

Africa's oldest languages. The results suggest that language first

evolved around 350,000–150,000 years ago, which is around the time when

modern

Homo sapiens evolved.

[32]

Estimates of this kind are not universally accepted, but jointly

considering genetic, archaeological, palaeontological and much other

evidence indicates that language probably emerged somewhere in

sub-Saharan Africa during the

Middle Stone Age, roughly contemporaneous with the speciation of

Homo sapiens.[33]

Language origin hypotheses

Early speculations

I cannot doubt that language owes its origin to the imitation and

modification, aided by signs and gestures, of various natural sounds,

the voices of other animals, and man's own instinctive cries.

—

Charles Darwin, 1871. The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex[34]

In 1861, historical linguist

Max Müller published a list of speculative theories concerning the origins of spoken language:

[35]

- Bow-wow. The bow-wow or cuckoo theory, which Müller attributed to the German philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder, saw early words as imitations of the cries of beasts and birds.

- Pooh-pooh. The pooh-pooh theory saw the first words as emotional interjections and exclamations triggered by pain, pleasure, surprise, etc.

- Ding-dong. Müller suggested what he called the ding-dong theory, which states that all things have a vibrating natural resonance, echoed somehow by man in his earliest words.

- Yo-he-ho. The yo-he-ho theory claims language emerged

from collective rhythmic labor, the attempt to synchronize muscular

effort resulting in sounds such as heave alternating with sounds such as ho.

- Ta-ta. This did not feature in Max Müller's list, having been proposed in 1930 by Sir Richard Paget.[36] According to the ta-ta theory, humans made the earliest words by tongue movements that mimicked manual gestures, rendering them audible.

Most scholars today consider all such theories not so much wrong—they

occasionally offer peripheral insights—as comically naïve and

irrelevant.

[37][38] The problem with these theories is that they are so narrowly mechanistic.

[citation needed] They assume that once our ancestors had stumbled upon the appropriate ingenious

mechanism for linking sounds with meanings, language automatically evolved and changed.

Problems of reliability and deception

From the perspective of modern science, the main obstacle to the

evolution of language-like communication in nature is not a mechanistic

one. Rather, it is the fact that symbols—arbitrary associations of

sounds or other perceptible forms with corresponding meanings—are

unreliable and may well be false.

[39] As the saying goes, "words are cheap".

[40] The problem of reliability was not recognized at all by Darwin, Müller or the other early evolutionary theorists.

Animal vocal signals are, for the most part, intrinsically reliable.

When a cat purrs, the signal constitutes direct evidence of the animal's

contented state. We trust the signal, not because the cat is inclined

to be honest, but because it just cannot fake that sound. Primate vocal

calls may be slightly more manipulable, but they remain reliable for the

same reason—because they are hard to fake.

[41] Primate social intelligence is "

Machiavellian"—self-serving and unconstrained by moral scruples. Monkeys and apes often attempt to

deceive each other, while at the same time remaining constantly on guard against falling victim to deception themselves.

[42][43]

Paradoxically, it is theorized that primates' resistance to deception

is what blocks the evolution of their signalling systems along

language-like lines. Language is ruled out because the best way to guard

against being deceived is to ignore all signals except those that are

instantly verifiable. Words automatically fail this test.

[20]

Words are easy to fake. Should they turn out to be lies, listeners

will adapt by ignoring them in favor of hard-to-fake indices or cues.

For language to work, then, listeners must be confident that those with

whom they are on speaking terms are generally likely to be honest.

[44] A peculiar feature of language is "

displaced reference",

which means reference to topics outside the currently perceptible

situation. This property prevents utterances from being corroborated in

the immediate "here" and "now". For this reason, language presupposes

relatively high levels of mutual trust in order to become established

over time as an

evolutionarily stable strategy.

This stability is born of a longstanding mutual trust and is what

grants language its authority. A theory of the origins of language must

therefore explain why humans could begin trusting cheap signals in ways

that other animals apparently cannot (see

signalling theory).

The 'mother tongues' hypothesis

The "mother tongues" hypothesis was proposed in 2004 as a possible solution to this problem.

[45] W. Tecumseh Fitch suggested that the Darwinian principle of '

kin selection'

[46]—the

convergence of genetic interests between relatives—might be part of the

answer. Fitch suggests that languages were originally 'mother tongues'.

If language evolved initially for communication between mothers and

their own biological offspring, extending later to include adult

relatives as well, the interests of speakers and listeners would have

tended to coincide. Fitch argues that shared genetic interests would

have led to sufficient trust and cooperation for intrinsically

unreliable signals—words—to become accepted as trustworthy and so begin

evolving for the first time.

Critics of this theory point out that kin selection is not unique to humans.

[47]

Other primate mothers also share genes with their progeny, as do all

other animals, so why is it only humans who speak? Furthermore, it is

difficult to believe that early humans restricted linguistic

communication to genetic kin: the incest taboo must have forced men and

women to interact and communicate with more distant relatives. So even

if we accept Fitch's initial premises, the extension of the posited

'mother tongue' networks from close relatives to more distant relatives

remains unexplained.

[47] Fitch argues, however, that the extended period of physical immaturity of human infants and the postnatal

growth of the human brain

give the human-infant relationship a different and more extended period

of intergenerational dependency than that found in any other species.

[45]

Another criticism of Fitch's theory is that language today is not

predominantly used to communicate to kin. Although Fitch's theory can

potentially explain the origin of human language, it cannot explain the

evolution of modern language.

[45]

The 'obligatory reciprocal altruism' hypothesis

Ib Ulbæk

[5] invokes another standard Darwinian principle—'

reciprocal altruism'

[48]—to

explain the unusually high levels of intentional honesty necessary for

language to evolve. 'Reciprocal altruism' can be expressed as the

principle that

if you scratch my back, I'll scratch yours. In linguistic terms, it would mean that

if you speak truthfully to me, I'll speak truthfully to you.

Ordinary Darwinian reciprocal altruism, Ulbæk points out, is a

relationship established between frequently interacting individuals. For

language to prevail across an entire community, however, the necessary

reciprocity would have needed to be enforced universally instead of

being left to individual choice. Ulbæk concludes that for language to

evolve, society as a whole must have been subject to moral regulation.

Critics point out that this theory fails to explain when, how, why or

by whom 'obligatory reciprocal altruism' could possibly have been

enforced.

[21] Various proposals have been offered to remedy this defect.

[21]

A further criticism is that language doesn't work on the basis of

reciprocal altruism anyway. Humans in conversational groups don't

withhold information to all except listeners likely to offer valuable

information in return. On the contrary, they seem to want to

advertise to the world

their access to socially relevant information, broadcasting that

information without expectation of reciprocity to anyone who will

listen.

[49]

The gossip and grooming hypothesis

Gossip, according to

Robin Dunbar in his book

Grooming, Gossip and the Evolution of Language, does for group-living humans what

manual grooming

does for other primates—it allows individuals to service their

relationships and so maintain their alliances on the basis of the

principle:

if you scratch my back, I'll scratch yours. Dunbar

argues that as humans began living in increasingly larger social groups,

the task of manually grooming all one's friends and acquaintances

became so time-consuming as to be unaffordable.

[50] In response to this problem, humans developed 'a cheap and ultra-efficient form of grooming'—

vocal grooming.

To keep allies happy, one now needs only to 'groom' them with low-cost

vocal sounds, servicing multiple allies simultaneously while keeping

both hands free for other tasks. Vocal grooming then evolved gradually

into vocal language—initially in the form of 'gossip'.

[50]

Dunbar's hypothesis seems to be supported by the fact that the

structure of language shows adaptations to the function of narration in

general.

[51]

Critics of this theory point out that the very efficiency of 'vocal

grooming'—the fact that words are so cheap—would have undermined its

capacity to signal commitment of the kind conveyed by time-consuming and

costly manual grooming.

[52]

A further criticism is that the theory does nothing to explain the

crucial transition from vocal grooming—the production of pleasing but

meaningless sounds—to the cognitive complexities of syntactical speech.

Ritual/speech coevolution

The ritual/speech coevolution theory was originally proposed by social anthropologist

Roy Rappaport[17] before being elaborated by anthropologists such as Chris Knight,

[20] Jerome Lewis,

[53] Nick Enfield,

[54] Camilla Power

[44] and Ian Watts.

[29] Cognitive scientist and robotics engineer

Luc Steels[55] is another prominent supporter of this general approach, as is biological anthropologist/neuroscientist

Terrence Deacon.

[56]

These scholars argue that there can be no such thing as a 'theory of

the origins of language'. This is because language is not a separate

adaptation but an internal aspect of something much wider—namely, human

symbolic culture as a whole.

[19]

Attempts to explain language independently of this wider context have

spectacularly failed, say these scientists, because they are addressing a

problem with no solution. Can we imagine a historian attempting to

explain the emergence of credit cards independently of the wider system

of which they are a part? Using a credit card makes sense only if you

have a bank account institutionally recognized within a certain kind of

advanced capitalist society—one where electronic communications

technology and digital computers have already been invented and fraud

can be detected and prevented. In much the same way, language would not

work outside a specific array of social mechanisms and institutions. For

example, it would not work for a nonhuman ape communicating with others

in the wild. Not even the cleverest nonhuman ape could make language

work under such conditions.

Lie and alternative, inherent in language ... pose problems to any

society whose structure is founded on language, which is to say all

human societies. I have therefore argued that if there are to be words

at all it is necessary to establish The Word, and that The Word is established by the invariance of liturgy.

Advocates of this school of thought point out that words are cheap.

As digital hallucinations, they are intrinsically unreliable. Should an

especially clever nonhuman ape, or even a group of articulate nonhuman

apes, try to use words in the wild, they would carry no conviction. The

primate vocalizations that do carry conviction—those they actually

use—are unlike words, in that they are emotionally expressive,

intrinsically meaningful and reliable because they are relatively costly

and hard to fake.

Language consists of digital contrasts whose cost is essentially

zero. As pure social conventions, signals of this kind cannot evolve in a

Darwinian social world — they are a theoretical impossibility.

[39]

Being intrinsically unreliable, language works only if you can build up

a reputation for trustworthiness within a certain kind of

society—namely, one where symbolic cultural facts (sometimes called

'institutional facts') can be established and maintained through

collective social endorsement.

[58] In any hunter-gatherer society, the basic mechanism for establishing trust in symbolic cultural facts is collective

ritual.

[59]

Therefore, the task facing researchers into the origins of language is

more multidisciplinary than is usually supposed. It involves addressing

the evolutionary emergence of human symbolic culture as a whole, with

language an important but subsidiary component.

Critics of the theory include Noam Chomsky, who terms it the

'non-existence' hypothesis—a denial of the very existence of language as

an object of study for natural science.

[60] Chomsky's own theory is that language emerged in an instant and in perfect form,

[61]

prompting his critics in turn to retort that only something that does

not exist—a theoretical construct or convenient scientific fiction—could

possibly emerge in such a miraculous way.

[18] The controversy remains unresolved.

Tool culture resilience and grammar in early Homo

While

it is possible to imitate the making of tools like those made by early

Homo under circumstances of demonstration being possible, research on

primate tool cultures show that non-verbal cultures are vulnerable to

environmental change. In particular, if the environment in which a skill

can be used disappears for a longer period of time than an individual

ape's or early human's lifespan, the skill will be lost if the culture

is imitative and non-verbal. Chimpanzees, macaques and capuchin monkeys

are all known to lose tool techniques under such circumstances.

Researchers on primate culture vulnerability therefore argue that since

early Homo species as far back as Homo habilis retained their tool

cultures despite many climate change cycles at the timescales of

centuries to millennia each, these species had sufficiently developed

language abilities to verbally describe complete procedures, and

therefore grammar and not only two-word "proto-language".

[62][63]

The theory that early Homo species had sufficiently developed brains

for grammar is also supported by researchers who study brain development

in children, noting that grammar is developed while connections across

the brain are still significantly lower than adult level. These

researchers argue that these lowered system requirements for grammatical

language make it plausible that the genus Homo had grammar at

connection levels in the brain that were significantly lower than those

of Homo sapiens and that more recent steps in the evolution of the human

brain were not about language.

[64][65]

Chomsky's single step theory

According to Chomsky's single mutation theory, the emergence of language resembled the formation of a crystal; with

digital infinity as the

seed crystal in a super-saturated primate brain, on the verge of blossoming into the human mind, by physical law, once

evolution added a single small but crucial keystone.

[66][61]

Whilst some suggest it follows from this theory that language appeared

rather suddenly within the history of human evolution, Chomsky, writing

with computational linguist and computer scientist Robert C. Berwick,

suggests it is completely compatible with modern biology. They note

"none of the recent accounts of human language evolution seem to have

completely grasped the shift from conventional Darwinism to its fully

stochastic

modern version—specifically, that there are stochastic effects not only

due to sampling like directionless drift, but also due to directed

stochastic variation in fitness, migration, and heritability—indeed, all

the "forces" that affect individual or gene frequencies. ... All this

can affect evolutionary outcomes—outcomes that as far as we can make out

are not brought out in recent books on the evolution of language, yet

would arise immediately in the case of any new genetic or individual

innovation, precisely the kind of scenario likely to be in play when

talking about language's emergence."

Citing evolutionary geneticist

Svante Pääbo they concur that a substantial difference must have occurred to differentiate

Homo sapiens from

Neanderthals

to "prompt the relentless spread of our species who had never crossed

open water up and out of Africa and then on across the entire planet in

just a few tens of thousands of years. ... What we do not see is any

kind of "gradualism" in new tool technologies or innovations like fire,

shelters, or figurative art." Berwick and Chomsky therefore suggest

language emerged approximately between 200,000 years ago and 60,000

years ago (between the arrival of the first anatomically modern humans

in southern Africa, and the last exodus from Africa, respectively).

"That leaves us with about 130,000 years, or approximately 5,000–6,000

generations of time for evolutionary change. This is not 'overnight in

one generation' as some have (incorrectly) inferred—but neither is it on

the scale of geological eons. It's time enough—within the ballpark for

what Nilsson and Pelger (1994) estimated as the time required for the

full evolution of a

vertebrate eye from a single cell, even without the invocation of any 'evo-devo' effects."

[67]

Gestural theory

The gestural theory states that human language developed from

gestures that were used for simple communication.

Two types of evidence support this theory.

- Gestural language and vocal language depend on similar neural systems. The regions on the cortex that are responsible for mouth and hand movements border each other.

- Nonhuman primates

can use gestures or symbols for at least primitive communication, and

some of their gestures resemble those of humans, such as the "begging

posture", with the hands stretched out, which humans share with

chimpanzees.[68]

Research has found strong support for the idea that

verbal language and sign language depend on similar neural structures. Patients who used sign language, and who suffered from a left-

hemisphere lesion, showed the same disorders with their sign language as vocal patients did with their oral language.

[69]

Other researchers found that the same left-hemisphere brain regions

were active during sign language as during the use of vocal or written

language.

[70]

Primate gesture is at least partially genetic: different nonhuman

apes will perform gestures characteristic of their species, even if they

have never seen another ape perform that gesture. For example, gorillas

beat their breasts. This shows that gestures are an intrinsic and

important part of primate communication, which supports the idea that

language evolved from gesture.

[71]

Further evidence suggests that gesture and language are linked. In

humans, manually gesturing has an effect on concurrent vocalizations,

thus creating certain natural vocal associations of manual efforts. Chimpanzees move their mouths when performing fine motor tasks. These

mechanisms may have played an evolutionary role in enabling the

development of intentional vocal communication as a supplement to

gestural communication. Voice modulation could have been prompted by

preexisting manual actions.

[71]

There is also the fact that, from infancy, gestures both supplement and predict speech.

[72][73]

This addresses the idea that gestures quickly change in humans from a

sole means of communication (from a very young age) to a supplemental

and predictive behavior that we use despite being able to communicate

verbally. This too serves as a parallel to the idea that gestures

developed first and language subsequently built upon it.

Two possible scenarios have been proposed for the development of language,

[74] one of which supports the gestural theory:

- Language developed from the calls of our ancestors.

- Language was derived from gesture.

The first perspective that language evolved from the calls of our

ancestors seems logical because both humans and animals make sounds or

cries. One evolutionary reason to refute this is that, anatomically, the

center that controls calls in monkeys and other animals is located in a

completely different part of the brain than in humans. In monkeys, this

center is located in the depths of the brain related to emotions. In

the human system, it is located in an area unrelated to emotion. Humans

can communicate simply to communicate—without emotions. So,

anatomically, this scenario does not work.

[74]

Therefore, we resort to the idea that language was derived from gesture

(we communicated by gesture first and sound was attached later).

The important question for gestural theories is why there was a shift to vocalization. Various explanations have been proposed:

- Our ancestors started to use more and more tools, meaning that their

hands were occupied and could no longer be used for gesturing.[75]

- Manual gesturing requires that speakers and listeners be visible to

one another. In many situations, they might need to communicate, even

without visual contact—for example after nightfall or when foliage

obstructs visibility.

- A composite hypothesis holds that early language took the form of part gestural and part vocal mimesis

(imitative 'song-and-dance'), combining modalities because all signals

(like those of nonhuman apes and monkeys) still needed to be costly in

order to be intrinsically convincing. In that event, each multi-media

display would have needed not just to disambiguate an intended meaning

but also to inspire confidence in the signal's reliability. The

suggestion is that only once community-wide contractual understandings

had come into force[76] could trust in communicative intentions be automatically assumed, at last allowing Homo sapiens

to shift to a more efficient default format. Since vocal distinctive

features (sound contrasts) are ideal for this purpose, it was only at

this point—when intrinsically persuasive body-language was no longer

required to convey each message—that the decisive shift from manual

gesture to our current primary reliance on spoken language occurred.[18][20][77]

A comparable hypothesis states that in 'articulate' language, gesture

and vocalisation are intrinsically linked, as language evolved from

equally intrinsically linked dance and song.

[15] Humans still use manual and facial gestures when they speak, especially when people meet who have no language in common.

[78] There are also, of course, a great number of

sign languages still in existence, commonly associated with

deaf communities. These sign languages are equal in complexity, sophistication, and expressive power, to any oral language

[citation needed].

The cognitive functions are similar and the parts of the brain used are

similar. The main difference is that the "phonemes" are produced on the

outside of the body, articulated with hands, body, and facial

expression, rather than inside the body articulated with tongue, teeth,

lips, and breathing.

[citation needed] (Compare the

motor theory of speech perception.)

Critics of gestural theory note that it is difficult to name serious reasons why the initial pitch-based

vocal

communication (which is present in primates) would be abandoned in

favor of the much less effective non-vocal, gestural communication.

[citation needed] However,

Michael Corballis

has pointed out that it is supposed that primate vocal communication

(such as alarm calls) cannot be controlled consciously, unlike hand

movement, and thus is not credible as precursor to human language;

primate vocalization is rather homologous to and continued in

involuntary reflexes (connected with basic human emotions) such as

screams or laughter (the fact that these can be faked does not disprove

the fact that genuine involuntary responses to fear or surprise exist).

[citation needed]

Also, gesture is not generally less effective, and depending on the

situation can even be advantageous, for example in a loud environment or

where it is important to be silent, such as on a hunt. Other challenges

to the "gesture-first" theory have been presented by researchers in

psycholinguistics, including

David McNeill.

[citation needed]

Tool-use associated sound in the evolution of language

Proponents

of the motor theory of language evolution have primarily focused on the

visual domain and communication through observation of movements. The

Tool-use sound hypothesis suggests that the production and perception of sound, also contributed substantially, particularly

incidental sound of locomotion (

ISOL) and

tool-use sound (

TUS). Human bipedalism resulted in rhythmic and more predictable

ISOL.

That may have stimulated the evolution of musical abilities, auditory

working memory, and abilities to produce complex vocalizations, and to

mimic natural sounds.

[80] Since the human brain proficiently extracts information about objects and events from the sounds they produce,

TUS, and mimicry of

TUS,

might have achieved an iconic function. The prevalence of sound

symbolism in many extant languages supports this idea. Self-produced TUS

activates multimodal brain processing (

motor neurons, hearing,

proprioception, touch, vision), and

TUS

stimulates primate audiovisual mirror neurons, which is likely to

stimulate the development of association chains. Tool use and auditory

gestures involve motor-processing of the forelimbs, which is associated

with the evolution of vertebrate vocal communication. The production,

perception, and mimicry of

TUS may have resulted in a limited number of vocalizations or protowords that were associated with tool use.

A new way to communicate about tools, especially when out of sight,

would have had selective advantage. A gradual change in acoustic

properties and/or meaning could have resulted in arbitrariness and an

expanded repertoire of words. Humans have been increasingly exposed to

TUS over millions of years, coinciding with the period during which spoken language evolved.

Mirror neurons and language origins

In humans,

functional MRI studies have reported finding areas homologous to the monkey

mirror neuron system in the

inferior frontal cortex, close to

Broca's area,

one of the language regions of the brain. This has led to suggestions

that human language evolved from a gesture performance/understanding

system implemented in mirror neurons. Mirror neurons have been said to

have the potential to provide a mechanism for action-understanding,

imitation-learning, and the simulation of other people's behavior.

[81] This hypothesis is supported by some

cytoarchitectonic homologies between monkey premotor area F5 and human Broca's area.

[82] Rates of

vocabulary expansion link to the ability of

children to vocally mirror non-words and so to acquire the new word pronunciations. Such

speech repetition occurs automatically, quickly

[83] and separately in the brain to

speech perception.

[84][85] Moreover, such vocal imitation can occur without comprehension such as in

speech shadowing[86] and

echolalia.

[82][87]

Further evidence for this link comes from a recent study in which the

brain activity of two participants was measured using fMRI while they

were gesturing words to each other using hand gestures with a game of

charades—a modality that some have suggested might represent the evolutionary precursor of human language. Analysis of the data using

Granger Causality

revealed that the mirror-neuron system of the observer indeed reflects

the pattern of activity of in the motor system of the sender, supporting

the idea that the motor concept associated with the words is indeed

transmitted from one brain to another using the mirror system.

[88]

Not all linguists agree with the above arguments, however. In

particular, supporters of Noam Chomsky argue against the possibility

that the mirror neuron system can play any role in the hierarchical

recursive structures essential to syntax.

[89]

Putting the baby down theory

According to

Dean Falk's

'putting the baby down' theory, vocal interactions between early

hominid mothers and infants sparked a sequence of events that led,

eventually, to our ancestors' earliest words.

[90]

The basic idea is that evolving human mothers, unlike their

counterparts in other primates, couldn't move around and forage with

their infants clinging onto their backs. Loss of fur in the human case

left infants with no means of clinging on. Frequently, therefore,

mothers had to put their babies down. As a result, these babies needed

to be reassured that they were not being abandoned. Mothers responded by

developing 'motherese'—an infant-directed communicative system

embracing facial expressions, body language, touching, patting,

caressing, laughter, tickling and emotionally expressive contact calls.

The argument is that language somehow developed out of all this.

[90]

In

The Mental and Social Life of Babies, psychologist

Kenneth Kaye

noted that no usable adult language could have evolved without

interactive communication between very young children and adults. "No

symbolic system could have survived from one generation to the next if

it could not have been easily acquired by young children under their

normal conditions of social life."

[91]

Grammaticalisation theory

'

Grammaticalisation'

is a continuous historical process in which free-standing words develop

into grammatical appendages, while these in turn become ever more

specialized and grammatical. An initially 'incorrect' usage, in becoming

accepted, leads to unforeseen consequences, triggering knock-on effects

and extended sequences of change. Paradoxically, grammar evolves

because, in the final analysis, humans care less about grammatical

niceties than about making themselves understood.

[92] If this is how grammar evolves today, according to this school of

thought, we can legitimately infer similar principles at work among our

distant ancestors, when grammar itself was first being established.

[93][94][95]

In order to reconstruct the evolutionary transition from early

language to languages with complex grammars, we need to know which

hypothetical sequences are plausible and which are not. In order to

convey abstract ideas, the first recourse of speakers is to fall back on

immediately recognizable concrete imagery, very often deploying

metaphors rooted in shared bodily experience.

[96]

A familiar example is the use of concrete terms such as 'belly' or

'back' to convey abstract meanings such as 'inside' or 'behind'. Equally

metaphorical is the strategy of representing temporal patterns on the

model of spatial ones. For example, English speakers might say 'It is

going to rain,' modeled on 'I am going to London.' This can be

abbreviated colloquially to 'It's gonna rain.' Even when in a hurry, we

don't say 'I'm gonna London'—the contraction is restricted to the job of

specifying tense. From such examples we can see why grammaticalization

is consistently unidirectional—from concrete to abstract meaning, not

the other way around.

[93]

Grammaticalization theorists picture early language as simple, perhaps consisting only of nouns.

[95]p. 111

Even under that extreme theoretical assumption, however, it is

difficult to imagine what would realistically have prevented people from

using, say, 'spear' as if it were a verb ('Spear that pig!'). People

might have used their nouns as verbs or their verbs as nouns as occasion

demanded. In short, while a noun-only language might seem theoretically

possible, grammaticalization theory indicates that it cannot have

remained fixed in that state for any length of time.

[93][97]

Creativity drives grammatical change.

[97]

This presupposes a certain attitude on the part of listeners. Instead

of punishing deviations from accepted usage, listeners must prioritize

imaginative mind-reading. Imaginative creativity—emitting a leopard

alarm when no leopard was present, for example—is not the kind of

behavior which, say,

vervet monkeys would appreciate or reward.

[98] Creativity and reliability are incompatible demands; for

'Machiavellian' primates as for animals generally, the overriding

pressure is to demonstrate reliability.

[99] If humans escape these constraints, it is because in our case, listeners are primarily interested in mental states.

To focus on mental states is to accept fictions—inhabitants of the

imagination—as potentially informative and interesting. Take the use of

metaphor. A metaphor is, literally, a false statement.

[100] Think of Romeo's declaration, 'Juliet is the sun!' Juliet is a woman,

not a ball of plasma in the sky, but human listeners are not (or not

usually) pedants insistent on point-by-point factual accuracy. They want

to know what the speaker has in mind. Grammaticalization is essentially

based on metaphor. To outlaw its use would be to stop grammar from

evolving and, by the same token, to exclude all possibility of

expressing abstract thought.

[96][101]

A criticism of all this is that while grammaticalization theory might

explain language change today, it does not satisfactorily address the

really difficult challenge—explaining the initial transition from

primate-style communication to language as we know it. Rather, the

theory assumes that language already exists. As Bernd Heine and Tania

Kuteva acknowledge: "Grammaticalization requires a linguistic system

that is used regularly and frequently within a community of speakers and

is passed on from one group of speakers to another".

[95] Outside modern humans, such conditions do not prevail.

Evolution-Progression Model

Human

language is used for self-expression; however, expression displays

different stages. The consciousness of self and feelings represents the

stage immediately prior to the external, phonetic expression of feelings

in the form of sound, i.e., language. Intelligent animals such as

dolphins, Eurasian magpies, and chimpanzees live in communities, wherein

they assign themselves roles for group survival and show emotions such

as sympathy.

[102] When such animals view their reflection (mirror test), they recognize themselves and exhibit self-consciousness.

[103]

Notably, humans evolved in a quite different environment than that of

these animals. The human environment accommodated the development of

interaction, self-expression, and tool-making as survival became easier

with the advancement of tools, shelters, and fire-making.

[104]

The increasing brain size allowed advanced provisioning and tools and

the technological advances during the Palaeolithic era that built upon

the previous evolutionary innovations of bipedalism and hand versatility

allowed the development of human language.

[citation needed]

Self-domesticated ape theory

According to a study investigating the song differences between

white-rumped munias and its domesticated counterpart (

Bengalese finch),

the wild munias use a highly stereotyped song sequence, whereas the

domesticated ones sing a highly unconstrained song. In wild finches,

song syntax is subject to female preference—

sexual selection—and

remains relatively fixed. However, in the Bengalese finch, natural

selection is replaced by breeding, in this case for colorful plumage,

and thus, decoupled from selective pressures, stereotyped song syntax is

allowed to drift. It is replaced, supposedly within 1000 generations,

by a variable and learned sequence. Wild finches, moreover, are thought

incapable of learning song sequences from other finches.

[105] In the field of

bird vocalization,

brains capable of producing only an innate song have very simple neural

pathways: the primary forebrain motor center, called the robust nucleus

of

arcopallium,

connects to midbrain vocal outputs, which in turn project to brainstem

motor nuclei. By contrast, in brains capable of learning songs, the

arcopallium receives input from numerous additional forebrain regions,

including those involved in learning and social experience. Control over

song generation has become less constrained, more distributed, and more

flexible.

[106]

One way to think about human evolution is that we are

self-domesticated apes. Just as domestication relaxed selection for

stereotypic songs in the finches—mate choice was supplanted by choices

made by the aesthetic sensibilities of bird breeders and their

customers—so might our cultural domestication have relaxed selection on

many of our primate behavioral traits, allowing old pathways to

degenerate and reconfigure. Given the highly indeterminate way that

mammalian brains develop—they basically construct themselves "bottom

up", with one set of neuronal interactions setting the stage for the

next round of interactions—degraded pathways would tend to seek out and

find new opportunities for synaptic hookups. Such inherited

de-differentiations of brain pathways might have contributed to the

functional complexity that characterizes human language. And, as

exemplified by the finches, such de-differentiations can occur in very

rapid time-frames.

[107]

Speech and language for communication

A distinction can be drawn between

speech and

language.

Language is not necessarily spoken: it might alternatively be written

or signed. Speech is among a number of different methods of encoding and

transmitting linguistic information, albeit arguably the most natural

one.

[108]

Some scholars view language as an initially cognitive development,

its 'externalisation' to serve communicative purposes occurring later in

human evolution. According to one such school of thought, the key

feature distinguishing human language is

recursion,

[109] (in this context, the iterative embedding of phrases within phrases). Other scholars—notably

Daniel Everett—deny that recursion is universal, citing certain languages (e.g.

Pirahã) which allegedly lack this feature.

[110]

The ability to ask questions is considered by some to distinguish language from non-human systems of communication.

[111] Some captive primates (notably

bonobos and

chimpanzees),

having learned to use rudimentary signing to communicate with their

human trainers, proved able to respond correctly to complex questions

and requests. Yet they failed to ask even the simplest questions

themselves.

[citation needed] Conversely, human children are able to ask their first questions (using only question

intonation)

at the babbling period of their development, long before they start

using syntactic structures. Although babies from different cultures

acquire native languages from their social environment, all languages of

the world without exception—tonal, non-tonal, intonational and

accented—use similar rising "question intonation" for

yes–no questions.

[112][113] This fact is a strong evidence of the universality of

question intonation.

In general, according to some authors, sentence intonation/pitch is

pivotal in spoken grammar and is the basic information used by children

to learn the grammar of whatever language.

[15]

Cognitive development and language

One of the intriguing abilities that language users have is that of high-level

reference (or

deixis),

the ability to refer to things or states of being that are not in the

immediate realm of the speaker. This ability is often related to theory

of mind, or an awareness of the other as a being like the self with

individual wants and intentions. According to Chomsky, Hauser and Fitch

(2002), there are six main aspects of this high-level reference system:

- Theory of mind

- Capacity to acquire non-linguistic conceptual representations, such as the object/kind distinction

- Referential vocal signals

- Imitation as a rational, intentional system

- Voluntary control over signal production as evidence of intentional communication

- Number representation[109]

Theory of mind

Simon Baron-Cohen (1999) argues that theory of mind must have preceded language use, based on evidence

[clarification needed]

of use of the following characteristics as much as 40,000 years ago:

intentional communication, repairing failed communication, teaching,

intentional persuasion, intentional deception, building shared plans and

goals, intentional sharing of focus or topic, and pretending. Moreover,

Baron-Cohen argues that many primates show some, but not all, of these

abilities.

[citation needed] Call and Tomasello's research on

chimpanzees

supports this, in that individual chimps seem to understand that other

chimps have awareness, knowledge, and intention, but do not seem to

understand false beliefs. Many primates show some tendencies toward a

theory of mind, but not a full one as humans have.

[citation needed]

Ultimately, there is some consensus within the field that a theory of

mind is necessary for language use. Thus, the development of a full

theory of mind in humans was a necessary precursor to full language use.

[citation needed]

Number representation

In

one particular study, rats and pigeons were required to press a button a

certain number of times to get food. The animals showed very accurate

distinction for numbers less than four, but as the numbers increased,

the error rate increased.

[109]

Matsuzawa (1985) attempted to teach chimpanzees Arabic numerals. The

difference between primates and humans in this regard was very large, as

it took the chimps thousands of trials to learn 1–9 with each number

requiring a similar amount of training time; yet, after learning the

meaning of 1, 2 and 3 (and sometimes 4), children easily comprehend the

value of greater integers by using a successor function (i.e. 2 is 1

greater than 1, 3 is 1 greater than 2, 4 is 1 greater than 3; once 4 is

reached it seems most children have an

"a-ha!" moment and understand that the value of any integer

n

is 1 greater than the previous integer). Put simply, other primates

learn the meaning of numbers one by one, similar to their approach to

other referential symbols, while children first learn an arbitrary list

of symbols (1, 2, 3, 4...) and then later learn their precise meanings.

[114]

These results can be seen as evidence for the application of the

"open-ended generative property" of language in human numeral cognition.

[109]

Linguistic structures

Lexical-phonological principle

Hockett (1966) details a list of features regarded as essential to describing human language.

[115] In the domain of the lexical-phonological principle, two features of this list are most important:

- Productivity: users can create and understand completely novel messages.

- New messages are freely coined by blending, analogizing from, or transforming old ones.

- Either new or old elements are freely assigned new semantic loads by

circumstances and context. This says that in every language, new idioms

constantly come into existence.

- Duality (of Patterning): a large number of meaningful elements are

made up of a conveniently small number of independently meaningless yet

message-differentiating elements.

The sound system of a language is composed of a finite set of simple phonological items. Under the specific

phonotactic rules of a given language, these items can be recombined and concatenated, giving rise to

morphology

and the open-ended lexicon. A key feature of language is that a simple,

finite set of phonological items gives rise to an infinite lexical

system wherein rules determine the form of each item, and meaning is

inextricably linked with form. Phonological syntax, then, is a simple

combination of pre-existing phonological units. Related to this is

another essential feature of human language: lexical syntax, wherein

pre-existing units are combined, giving rise to semantically novel or

distinct lexical items.

[citation needed]

Certain elements of the lexical-phonological principle are known to

exist outside of humans. While all (or nearly all) have been documented

in some form in the natural world, very few coexist within the same

species. Bird-song, singing nonhuman apes, and the songs of whales all

display phonological syntax, combining units of sound into larger

structures apparently devoid of enhanced or novel meaning. Certain other

primate species do have simple phonological systems with units

referring to entities in the world. However, in contrast to human

systems, the units in these primates' systems normally occur in

isolation, betraying a lack of lexical syntax. There is new evidence to

suggest that Campbell's monkeys also display lexical syntax, combining

two calls (a predator alarm call with a "boom", the combination of which

denotes a lessened threat of danger), however it is still unclear

whether this is a lexical or a morphological phenomenon.

[citation needed]

Pidgins and creoles

Pidgins are significantly simplified languages with only rudimentary

grammar and a restricted vocabulary. In their early stage pidgins mainly

consist of nouns, verbs, and adjectives with few or no articles,

prepositions, conjunctions or auxiliary verbs. Often the grammar has no

fixed

word order and the words have no

inflection.

[116]

If contact is maintained between the groups speaking the pidgin for

long periods of time, the pidgins may become more complex over many

generations. If the children of one generation adopt the pidgin as their

native language it develops into a

creole language,

which becomes fixed and acquires a more complex grammar, with fixed

phonology, syntax, morphology, and syntactic embedding. The syntax and

morphology of such languages may often have local innovations not

obviously derived from any of the parent languages.

Studies of creole languages around the world have suggested that they

display remarkable similarities in grammar and are developed uniformly

from pidgins in a single generation. These similarities are apparent

even when creoles do not share any common language origins. In addition,

creoles share similarities despite being developed in isolation from

each other.

Syntactic similarities include

subject–verb–object

word order. Even when creoles are derived from languages with a

different word order they often develop the SVO word order. Creoles tend

to have similar usage patterns for definite and indefinite articles,

and similar movement rules for phrase structures even when the parent

languages do not.

[116]

Evolutionary timeline

Primate communication

Field primatologists can give us useful insights into

great ape communication in the wild.

[30]

An important finding is that nonhuman primates, including the other

great apes, produce calls that are graded, as opposed to categorically

differentiated, with listeners striving to evaluate subtle gradations in

signalers' emotional and bodily states. Nonhuman apes seemingly find it

extremely difficult to produce vocalizations in the absence of the

corresponding emotional states.

[41] In captivity, nonhuman apes have been taught rudimentary forms of sign language or have been persuaded to use

lexigrams—symbols that do not graphically resemble the corresponding words—on computer keyboards. Some nonhuman apes, such as

Kanzi, have been able to learn and use hundreds of lexigrams.

[117][118]

The

Broca's and

Wernicke's areas

in the primate brain are responsible for controlling the muscles of the

face, tongue, mouth, and larynx, as well as recognizing sounds.

Primates are known to make "vocal calls", and these calls are generated

by circuits in the

brainstem and

limbic system.

[119]

In the wild, the communication of

vervet monkeys has been the most extensively studied.

[116]

They are known to make up to ten different vocalizations. Many of these

are used to warn other members of the group about approaching

predators. They include a "leopard call", a "snake call", and an "eagle

call".

[120]

Each call triggers a different defensive strategy in the monkeys who

hear the call and scientists were able to elicit predictable responses

from the monkeys using loudspeakers and prerecorded sounds. Other

vocalizations may be used for identification. If an infant monkey calls,

its mother turns toward it, but other vervet mothers turn instead

toward that infant's mother to see what she will do.

[121][122]

Similarly, researchers have demonstrated that chimpanzees (in

captivity) use different "words" in reference to different foods. They

recorded vocalizations that chimps made in reference, for example, to

grapes, and then other chimps pointed at pictures of grapes when they

heard the recorded sound.

[123][124]

Ardipithecus ramidus

A study published in

Homo: Journal of Comparative Human Biology in 2017 claims that

A. ramidus,

a hominin dated at approximately 4.5Ma, shows the first evidence of an

anatomical shift in the hominin lineage suggestive of increased vocal

capability.

[125] This study compared the skull of

A. ramidus with twenty nine chimpanzee skulls of different ages and found that in numerous features

A. ramidus

clustered with the infant and juvenile measures as opposed to the adult

measures. Significantly, such affinity with the shape dimensions of

infant and juvenile chimpanzee skull architecture was argued may have

resulted in greater vocal capability. This assertion was based on the

notion that the chimpanzee vocal tract ratios that prevent speech are a

result of growth factors associated with puberty—growth factors absent

in

A. ramidus ontogeny.

A. ramidus was also found to have a

degree of cervical lordosis more conducive to vocal modulation when

compared with chimpanzees as well as cranial base architecture

suggestive of increased vocal capability.

What was significant in this study was the observation that the

changes in skull architecture that correlate with reduced aggression are

the same changes necessary for the evolution of early hominin vocal

ability. In integrating data on anatomical correlates of primate mating

and social systems with studies of skull and vocal tract architecture

that facilitate speech production, the authors argue that

paleoanthropologists to date have failed to grasp the important relationship between early hominin social evolution and language capacity.

In the paleoanthropological literature, these changes in early

hominin skull morphology [reduced facial prognathism and lack of canine

armoury] have to date been analysed in terms of a shift in mating and

social behaviour, with little consideration given to vocally mediated

sociality. Similarly, in the literature on language evolution there is a

distinct lacuna regarding links between craniofacial correlates of

social and mating systems and vocal ability. These are surprising

oversights given that pro-sociality and vocal capability require

identical alterations to the common ancestral skull and skeletal

configuration. We therefore propose a model which integrates data on

whole organism morphogenesis with evidence for a potential early

emergence of hominin socio-vocal adaptations. Consequently, we suggest

vocal capability may have evolved much earlier than has been

traditionally proposed. Instead of emerging in the genus

Homo, we

suggest the palaeoecological context of late Miocene and early Pliocene

forests and woodlands facilitated the evolution of hominin socio-vocal

capability. We also propose that paedomorphic morphogenesis of the skull

via the process of self-domestication enabled increased levels of

pro-social behaviour, as well as increased capacity for socially

synchronous vocalisation to evolve at the base of the hominin clade.

[125]

While the skull of

A. ramidus, according to the authors, lacks

the anatomical impediments to speech evident in chimpanzees, it is

unclear what the vocal capabilities of this early hominin were. While

they suggest

A. ramidus—based on similar vocal tract ratios—may

have had vocal capabilities equivalent to a modern human infant or very

young child, they concede this is obviously a debatable and speculative

hypothesis. However, they do claim that changes in skull architecture

through processes of social selection were a necessary prerequisite for

language evolution. As they write:

We propose that as a result of paedomorphic morphogenesis of the cranial base and craniofacial morphology Ar. ramidus

would have not been limited in terms of the mechanical components of

speech production as chimpanzees and bonobos are. It is possible that Ar. ramidus

had vocal capability approximating that of chimpanzees and bonobos,

with its idiosyncratic skull morphology not resulting in any significant

advances in speech capability. In this sense the anatomical features

analysed in this essay would have been exapted in later more voluble

species of hominin. However, given the selective advantages of

pro-social vocal synchrony, we suggest the species would have developed

significantly more complex vocal abilities than chimpanzees and bonobos.[125]

Early Homo

Regarding articulation, there is considerable speculation about the language capabilities of early

Homo (2.5 to 0.8 million years ago). Anatomically, some scholars believe features of

bipedalism, which developed in

australopithecines

around 3.5 million years ago, would have brought changes to the skull,

allowing for a more L-shaped vocal tract. The shape of the tract and a

larynx positioned relatively low in the neck are necessary prerequisites

for many of the sounds humans make, particularly vowels.

[citation needed] Other scholars believe that, based on the position of the larynx, not even

Neanderthals had the anatomy necessary to produce the full range of sounds modern humans make.

[126][127] It was earlier proposed that differences between

Homo sapiens and Neanderthal vocal tracts could be seen in fossils, but the finding that the Neanderthal

hyoid bone (see below) was identical to that found in

Homo sapiens

has weakened these theories. Still another view considers the lowering

of the larynx as irrelevant to the development of speech.

[128]

Archaic Homo sapiens

Steven Mithen proposed the term

Hmmmmm for the pre-linguistic system of communication used by archaic

Homo. beginning with

Homo ergaster and reaching the highest sophistication in the

Middle Pleistocene with

Homo heidelbergensis and

Homo neanderthalensis. Hmmmmm is an acronym for

holistic (non-compositional),

manipulative (utterances are commands or suggestions, not descriptive statements),

multi-

modal (acoustic as well as gestural and facial),

musical, and

mimetic.

[129]

Homo heidelbergensis

Homo heidelbergensis was a close relative (most probably a migratory descendant) of

Homo ergaster. Some researchers believe this species to be the first hominin to make

controlled vocalizations, possibly mimicking animal vocalizations,

[129] and that as

Homo heidelbergensis developed more sophisticated culture, proceeded from this point and possibly developed an early form of symbolic language.

Homo neanderthalensis

The discovery in 1989 of the (Neanderthal) Kebara 2 hyoid bone

suggests that Neanderthals may have been anatomically capable of

producing sounds similar to modern humans.

[130][131] The

hypoglossal nerve,

which passes through the hypoglossal canal, controls the movements of

the tongue, which may have enabled voicing for size exaggeration (see

size exaggeration hypothesis below) or may reflect speech abilities.

[25][132][133][134][135][136]

However, although Neanderthals may have been anatomically able to speak,

Richard G. Klein

in 2004 doubted that they possessed a fully modern language. He largely

bases his doubts on the fossil record of archaic humans and their stone

tool kit. For 2 million years following the emergence of

Homo habilis,

the stone tool technology of hominins changed very little. Klein, who

has worked extensively on ancient stone tools, describes the crude stone

tool kit of archaic humans as impossible to break down into categories

based on their function, and reports that Neanderthals seem to have had

little concern for the final aesthetic form of their tools. Klein argues

that the Neanderthal brain may have not reached the level of complexity

required for modern speech, even if the physical apparatus for speech

production was well-developed.

[137][138] The issue of the Neanderthal's level of cultural and technological sophistication remains a controversial one.

Based on computer simulations used to evaluate that evolution of

language that resulted in showing three stages in the evolution of

syntax, Neanderthals are thought to have been in stage 2, showing they

had something more evolved than proto-language but not quite as complex

as the language of modern humans.

[139]

Homo sapiens

Anatomically modern humans begin to

appear in the fossil record in Ethiopia some 200,000 years ago.

[140]

Although there is still much debate as to whether behavioural modernity

emerged in Africa at around the same time, a growing number of

archaeologists nowadays invoke the southern African Middle Stone Age use

of red ochre pigments—for example at

Blombos Cave—as evidence that modern anatomy and behaviour co-evolved.

[141]

These archaeologists argue strongly that if modern humans at this early

stage were using red ochre pigments for ritual and symbolic purposes,

they probably had symbolic language as well.

[142]

According to the

recent African origins hypothesis, from around 60,000 – 50,000 years ago

[143]

a group of humans left Africa and began migrating to occupy the rest of

the world, carrying language and symbolic culture with them.

[144]

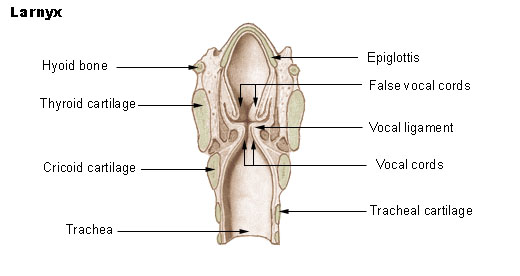

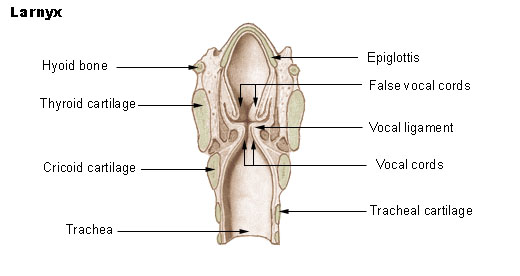

The descended larynx

The

larynx or

voice box is an organ in the neck housing the

vocal folds, which are responsible for

phonation. In humans, the larynx is

descended. Our species is not unique in this respect: goats, dogs, pigs and tamarins lower the larynx temporarily, to emit loud calls.

[145]

Several deer species have a permanently lowered larynx, which may be

lowered still further by males during their roaring displays.

[146] Lions, jaguars, cheetahs and domestic cats also do this.

[147]

However, laryngeal descent in nonhumans (according to Philip Lieberman)

is not accompanied by descent of the hyoid; hence the tongue remains

horizontal in the oral cavity, preventing it from acting as a pharyngeal

articulator.

[148]

| Larynx |

|

|

|

Despite all this, scholars remain divided as to how "special" the

human vocal tract really is. It has been shown that the larynx does

descend to some extent during development in chimpanzees, followed by

hyoidal descent.

[149]

As against this, Philip Lieberman points out that only humans have

evolved permanent and substantial laryngeal descent in association with

hyoidal descent, resulting in a curved tongue and two-tube vocal tract

with 1:1 proportions. Uniquely in the human case, simple contact between

the epiglottis and velum is no longer possible, disrupting the normal

mammalian separation of the respiratory and digestive tracts during

swallowing. Since this entails substantial costs—increasing the risk of

choking while swallowing food—we are forced to ask what benefits might

have outweighed those costs. The obvious benefit—so it is claimed—must

have been speech. But this idea has been vigorously contested. One

objection is that humans are in fact

not seriously at risk of choking on food: medical statistics indicate that accidents of this kind are extremely rare.

[150] Another objection is that in the view of most scholars, speech as we

know it emerged relatively late in human evolution, roughly

contemporaneously with the emergence of

Homo sapiens.[32]

A development as complex as the reconfiguration of the human vocal

tract would have required much more time, implying an early date of

origin. This discrepancy in timescales undermines the idea that human

vocal flexibility was

initially driven by selection pressures for speech, thus not excluding that it was selected for e.g. improved singing ability.

The size exaggeration hypothesis

To lower the larynx is to increase the length of the vocal tract, in turn lowering

formant

frequencies so that the voice sounds "deeper"—giving an impression of

greater size. John Ohala argues that the function of the lowered larynx

in humans, especially males, is probably to enhance threat displays

rather than speech itself.

[151]

Ohala points out that if the lowered larynx were an adaptation for

speech, we would expect adult human males to be better adapted in this

respect than adult females, whose larynx is considerably less low. In

fact, females invariably outperform males in verbal tests

[citation needed],

falsifying this whole line of reasoning. W. Tecumseh Fitch likewise

argues that this was the original selective advantage of laryngeal

lowering in our species. Although (according to Fitch) the initial

lowering of the larynx in humans had nothing to do with speech, the

increased range of possible formant patterns was subsequently co-opted

for speech. Size exaggeration remains the sole function of the extreme

laryngeal descent observed in male deer. Consistent with the size

exaggeration hypothesis, a second descent of the larynx occurs at

puberty in humans, although only in males. In response to the objection

that the larynx is descended in human females, Fitch suggests that

mothers vocalising to protect their infants would also have benefited

from this ability.

[152]

Phonemic diversity

In 2011, Quentin Atkinson published a survey of

phonemes from 500 different languages as well as

language families

and compared their phonemic diversity by region, number of speakers and

distance from Africa. The survey revealed that African languages had

the largest number of phonemes, and

Oceania

and South America had the smallest number. After allowing for the

number of speakers, the phonemic diversity was compared to over 2000

possible origin locations. Atkinson's "best fit" model is that language

originated in central and southern Africa between 80,000 and 160,000

years ago. This predates the hypothesized

southern coastal peopling

of Arabia, India, southeast Asia, and Australia. It would also mean

that the origin of language occurred at the same time as the emergence

of symbolic culture.

[153]

History

In religion and mythology

The search for the origin of language has a long history rooted in

mythology. Most mythologies do not credit humans with the invention of language but speak of a

divine language predating human language. Mystical languages used to communicate with animals or spirits, such as the

language of the birds, are also common, and were of particular interest during the

Renaissance.

Vāc is the Hindu goddess of speech, or "speech personified". As

Brahman's "sacred utterance", she has a cosmological role as the "Mother of the

Vedas". The

Aztecs' story maintains that only a man,

Coxcox, and a woman,

Xochiquetzal,

survived a flood, having floated on a piece of bark. They found

themselves on land and begat many children who were at first born unable

to speak, but subsequently, upon the arrival of a

dove, were endowed with language, although each one was given a different speech such that they could not understand one another.

[154]

In the Old Testament, the Book of Genesis (11) says that God prevented the

Tower of Babel

from being completed through a miracle that made its construction

workers start speaking different languages. After this, they migrated to

other regions, grouped together according to which of the newly created

languages they spoke, explaining the origins of languages and nations

outside of the fertile crescent.

Historical experiments

History contains a number of anecdotes about people who attempted to

discover the origin of language by experiment. The first such tale was

told by

Herodotus (

Histories 2.2). He relates that Pharaoh Psammetichus (probably

Psammetichus I,

7th century BC) had two children raised by a shepherd, with the

instructions that no one should speak to them, but that the shepherd

should feed and care for them while listening to determine their first

words. When one of the children cried "bekos" with outstretched arms the

shepherd concluded that the word was

Phrygian,

because that was the sound of the Phrygian word for "bread". From this,

Psammetichus concluded that the first language was Phrygian. King