Behavioral epigenetics is the field of study examining the role of epigenetics in shaping animal (including human) behaviour. It seeks to explain how nurture shapes nature, where nature refers to biological heredity and nurture refers to virtually everything that occurs during the life-span (e.g., social-experience, diet and nutrition, and exposure to toxins). Behavioral epigenetics attempts to provide a framework for understanding how the expression of genes is influenced by experiences and the environment to produce individual differences in behaviour, cognition, personality, and mental health.

Epigenetic gene regulation involves changes other than to the sequence of DNA and includes changes to histones (proteins around which DNA is wrapped) and DNA methylation. These epigenetic changes can influence the growth of neurons in the developing brain as well as modify the activity of neurons in the adult brain. Together, these epigenetic changes in neuron structure and function can have a marked influence on an organism's behavior.

Background

In biology, and specifically genetics, epigenetics is the study of heritable changes in gene activity which are not caused by changes in the DNA sequence; the term can also be used to describe the study of stable, long-term alterations in the transcriptional potential of a cell that are not necessarily heritable.

Examples of mechanisms that produce such changes are DNA methylation and histone modification, each of which alters how genes are expressed without altering the underlying DNA sequence. Gene expression can be controlled through the action of repressor proteins that attach to silencer regions of the DNA.

DNA methylation turns a gene "off" – it results in the inability of genetic information to be read from DNA; removing the methyl tag can turn the gene back "on".

Epigenetics has a strong influence on the development of an organism and can alter the expression of individual traits. Epigenetic changes occur not only in the developing fetus, but also in individuals throughout the human life-span. Because some epigenetic modifications can be passed from one generation to the next, subsequent generations may be affected by the epigenetic changes that took place in the parents.

Discovery

The first documented example of epigenetics affecting behavior was provided by Michael Meaney and Moshe Szyf. While working at McGill University in Montréal in 2004, they discovered that the type and amount of nurturing a mother rat provides in the early weeks of the rat's infancy determines how that rat responds to stress later in life. This stress sensitivity was linked to a down-regulation in the expression of the glucocorticoid receptor in the brain. In turn, this down-regulation was found to be a consequence of the extent of methylation in the promoter region of the glucocorticoid receptor gene. Immediately after birth, Meaney and Szyf found that methyl groups repress the glucocorticoid receptor gene in all rat pups, making the gene unable to unwind from the histone in order to be transcribed, causing a decreased stress response. Nurturing behaviours from the mother rat were found to stimulate activation of stress signalling pathways that remove methyl groups from DNA. This releases the tightly wound gene, exposing it for transcription. The glucocorticoid gene is activated, resulting in lowered stress response. Rat pups that receive a less nurturing upbringing are more sensitive to stress throughout their life-span.

This pioneering work in rodents has been difficult to replicate in humans because of a general lack of availability human brain tissue for measurement of epigenetic changes.

Research into epigenetics in psychology

Anxiety and risk-taking

In a small clinical study in humans published in 2008, epigenetic differences were linked to differences in risk-taking and reactions to stress in monozygotic twins. The study identified twins with different life paths, wherein one twin displayed risk-taking behaviours, and the other displayed risk-averse behaviours. Epigenetic differences in DNA methylation of the CpG islands proximal to the DLX1 gene correlated with the differing behavior. The authors of the twin study noted that despite the associations between epigenetic markers and differences personality traits, epigenetics cannot predict complex decision-making processes like career selection.

Stress

Animal and human studies have found correlations between poor care during infancy and epigenetic changes that correlate with long-term impairments that result from neglect.

Studies in rats have shown correlations between maternal care in terms of the parental licking of offspring and epigenetic changes. A high level of licking results in a long-term reduction in stress response as measured behaviorally and biochemically in elements of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA). Further, decreased DNA methylation of the glucocorticoid receptor gene were found in offspring that experienced a high level of licking; the glucorticoid receptor plays a key role in regulating the HPA. The opposite is found in offspring that experienced low levels of licking, and when pups are switched, the epigenetic changes are reversed. This research provides evidence for an underlying epigenetic mechanism. Further support comes from experiments with the same setup, using drugs that can increase or decrease methylation. Finally, epigenetic variations in parental care can be passed down from one generation to the next, from mother to female offspring. Female offspring who received increased parental care (i.e., high licking) became mothers who engaged in high licking and offspring who received less licking became mothers who engaged in less licking.

In humans, a small clinical research study showed the relationship between prenatal exposure to maternal mood and genetic expression resulting in increased reactivity to stress in offspring. Three groups of infants were examined: those born to mothers medicated for depression with serotonin reuptake inhibitors; those born to depressed mothers not being treated for depression; and those born to non-depressed mothers. Prenatal exposure to depressed/anxious mood was associated with increased DNA methylation at the glucocorticoid receptor gene and to increased HPA axis stress reactivity. The findings were independent of whether the mothers were being pharmaceutically treated for depression.

Recent research has also shown the relationship of methylation of the maternal glucocorticoid receptor and maternal neural activity in response to mother-infant interactions on video. Longitudinal follow-up of those infants will be important to understand the impact of early caregiving in this high-risk population on child epigenetics and behavior.

Cognition

Learning and memory

A 2010 review discusses the role of DNA methylation in memory formation and storage, but the precise mechanisms involving neuronal function, memory, and methylation reversal remain unclear.

Studies in rodents have found that the environment exerts an influence on epigenetic changes related to cognition, in terms of learning and memory; environmental enrichment correlated with increased histone acetylation, and verification by administering histone deacetylase inhibitors induced sprouting of dendrites, an increased number of synapses, and reinstated learning behaviour and access to long-term memories. Research has also linked learning and long-term memory formation to reversible epigenetic changes in the hippocampus and cortex in animals with normal-functioning, non-damaged brains. In human studies, post-mortem brains from Alzheimer's patients show increased histone de-acetylase levels.

Psychopathology and mental health

Drug addiction

Environmental and epigenetic influences seem to work together to increase the risk of addiction. For example, environmental stress has been shown to increase the risk of substance abuse. In an attempt to cope with stress, alcohol and drugs can be used as an escape. Once substance abuse commences, however, epigenetic alterations may further exacerbate the biological and behavioural changes associated with addiction.

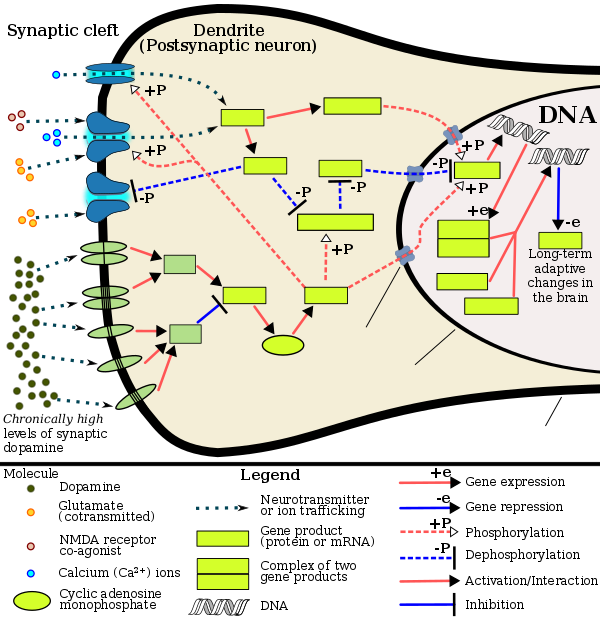

Even short-term substance abuse can produce long-lasting epigenetic changes in the brain of rodents, via DNA methylation and histone modification. Epigenetic modifications have been observed in studies on rodents involving ethanol, nicotine, cocaine, amphetamine, methamphetamine and opiates. Specifically, these epigenetic changes modify gene expression, which in turn increases the vulnerability of an individual to engage in repeated substance overdose in the future. In turn, increased substance abuse results in even greater epigenetic changes in various components of a rodent's reward system (e.g., in the nucleus accumbens). Hence, a cycle emerges whereby changes in areas of the reward system contribute to the long-lasting neural and behavioural changes associated with the increased likelihood of addiction, the maintenance of addiction and relapse. In humans, alcohol consumption has been shown to produce epigenetic changes that contribute to the increased craving of alcohol. As such, epigenetic modifications may play a part in the progression from the controlled intake to the loss of control of alcohol consumption. These alterations may be long-term, as is evidenced in smokers who still possess nicotine-related epigenetic changes ten years after cessation. Therefore, epigenetic modifications may account for some of the behavioural changes generally associated with addiction. These include: repetitive habits that increase the risk of disease, and personal and social problems; need for immediate gratification; high rates of relapse following treatment; and, the feeling of loss of control.

Evidence for related epigenetic changes has come from human studies involving alcohol, nicotine, and opiate abuse. Evidence for epigenetic changes stemming from amphetamine and cocaine abuse derives from animal studies. In animals, drug-related epigenetic changes in fathers have also been shown to negatively affect offspring in terms of poorer spatial working memory, decreased attention and decreased cerebral volume.

Eating disorders and obesity

Epigenetic changes may help to facilitate the development and maintenance of eating disorders via influences in the early environment and throughout the life-span. Pre-natal epigenetic changes due to maternal stress, behaviour and diet may later predispose offspring to persistent, increased anxiety and anxiety disorders. These anxiety issues can precipitate the onset of eating disorders and obesity, and persist even after recovery from the eating disorders.

Epigenetic differences accumulating over the life-span may account for the incongruent differences in eating disorders observed in monozygotic twins. At puberty, sex hormones may exert epigenetic changes (via DNA methylation) on gene expression, thus accounting for higher rates of eating disorders in men as compared to women. Overall, epigenetics contribute to persistent, unregulated self-control behaviours related to the urge to binge.

Schizophrenia

Epigenetic changes including hypomethylation of glutamatergic genes (i.e., NMDA-receptor-subunit gene NR3B and the promoter of the AMPA-receptor-subunit gene GRIA2) in the post-mortem human brains of schizophrenics are associated with increased levels of the neurotransmitter glutamate. Since glutamate is the most prevalent, fast, excitatory neurotransmitter, increased levels may result in the psychotic episodes related to schizophrenia. Epigenetic changes affecting a greater number of genes have been detected in men with schizophrenia as compared to women with the illness.

Population studies have established a strong association linking schizophrenia in children born to older fathers. Specifically, children born to fathers over the age of 35 years are up to three times more likely to develop schizophrenia. Epigenetic dysfunction in human male sperm cells, affecting numerous genes, have been shown to increase with age. This provides a possible explanation for increased rates of the disease in men. To this end, toxins (e.g., air pollutants) have been shown to increase epigenetic differentiation. Animals exposed to ambient air from steel mills and highways show drastic epigenetic changes that persist after removal from the exposure. Therefore, similar epigenetic changes in older human fathers are likely. Schizophrenia studies provide evidence that the nature versus nurture debate in the field of psychopathology should be re-evaluated to accommodate the concept that genes and the environment work in tandem. As such, many other environmental factors (e.g., nutritional deficiencies and cannabis use) have been proposed to increase the susceptibility of psychotic disorders like schizophrenia via epigenetics.

Bipolar disorder

Evidence for epigenetic modifications for bipolar disorder is unclear. One study found hypomethylation of a gene promoter of a prefrontal lobe enzyme (i.e., membrane-bound catechol-O-methyl transferase, or COMT) in post-mortem brain samples from individuals with bipolar disorder. COMT is an enzyme that metabolizes dopamine in the synapse. These findings suggest that the hypomethylation of the promoter results in over-expression of the enzyme. In turn, this results in increased degradation of dopamine levels in the brain. These findings provide evidence that epigenetic modification in the prefrontal lobe is a risk factor for bipolar disorder. However, a second study found no epigenetic differences in post-mortem brains from bipolar individuals.

Major depressive disorder

The causes of major depressive disorder (MDD) are poorly understood from a neuroscience perspective. The epigenetic changes leading to changes in glucocorticoid receptor expression and its effect on the HPA stress system discussed above, have also been applied to attempts to understand MDD.

Much of the work in animal models has focused on the indirect downregulation of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) by over-activation of the stress axis. Studies in various rodent models of depression, often involving induction of stress, have found direct epigenetic modulation of BDNF as well.

Psychopathy

Epigenetics may be relevant to aspects of psychopathic behaviour through methylation and histone modification. These processes are heritable but can also be influenced by environmental factors such as smoking and abuse. Epigenetics may be one of the mechanisms through which the environment can impact the expression of the genome. Studies have also linked methylation of genes associated with nicotine and alcohol dependence in women, ADHD, and drug abuse. It is probable that epigenetic regulation as well as methylation profiling will play an increasingly important role in the study of the play between the environment and genetics of psychopaths.

Suicide

A study of the brains of 24 suicide completers, 12 of whom had a history of child abuse and 12 who did not, found decreased levels of glucocorticoid receptor in victims of child abuse and associated epigenetic changes.

Social insects

Several studies have indicated DNA cytosine methylation linked to the social behavior of insects, such as honeybees and ants. In honeybees, when nurse bee switched from her in-hive tasks to out foraging, cytosine methylation marks are changing. When a forager bee was reversed to do nurse duties, the cytosine methylation marks were also reversed. Knocking down the DNMT3 in the larvae changed the worker to queen-like phenotype. Queen and worker are two distinguish castes with different morphology, behavior, and physiology. Studies in DNMT3 silencing also indicated DNA methylation may regulate gene alternative splicing and pre-mRNA maturation.

Limitations and future direction

Many researchers contribute information to the Human Epigenome Consortium. The aim of future research is to reprogram epigenetic changes to help with addiction, mental illness, age related changes, memory decline, and other issues. However, the sheer volume of consortium-based data makes analysis difficult. Most studies also focus on one gene. In actuality, many genes and interactions between them likely contribute to individual differences in personality, behaviour and health. As social scientists often work with many variables, determining the number of affected genes also poses methodological challenges. More collaboration between medical researchers, geneticists and social scientists has been advocated to increase knowledge in this field of study.

Limited access to human brain tissue poses a challenge to conducting human research. Not yet knowing if epigenetic changes in the blood and (non-brain) tissues parallel modifications in the brain, places even greater reliance on brain research. Although some epigenetic studies have translated findings from animals to humans, some researchers caution about the extrapolation of animal studies to humans. One view notes that when animal studies do not consider how the subcellular and cellular components, organs and the entire individual interact with the influences of the environment, results are too reductive to explain behaviour.

Some researchers note that epigenetic perspectives will likely be incorporated into pharmacological treatments. Others caution that more research is necessary as drugs are known to modify the activity of multiple genes and may, therefore, cause serious side effects. However, the ultimate goal is to find patterns of epigenetic changes that can be targeted to treat mental illness, and reverse the effects of childhood stressors, for example. If such treatable patterns eventually become well-established, the inability to access brains in living humans to identify them poses an obstacle to pharmacological treatment. Future research may also focus on epigenetic changes that mediate the impact of psychotherapy on personality and behaviour.

Most epigenetic research is correlational; it merely establishes associations. More experimental research is necessary to help establish causation. Lack of resources has also limited the number of intergenerational studies. Therefore, advancing longitudinal and multigenerational, experience-dependent studies will be critical to further understanding the role of epigenetics in psychology.