From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Medicine |

Medicine is the art, science, and practice of caring for a patient and managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment or palliation of their injury or disease. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care practices evolved to maintain and restore health by the prevention and treatment of illness. Contemporary medicine applies biomedical sciences, biomedical research, genetics, and medical technology to diagnose, treat, and prevent injury and disease, typically through pharmaceuticals or surgery, but also through therapies as diverse as psychotherapy, external splints and traction, medical devices, biologics, and ionizing radiation, amongst others.

Medicine has been practiced since prehistoric times, during most of which it was an art (an area of skill and knowledge) frequently having connections to the religious and philosophical beliefs of local culture. For example, a medicine man would apply herbs and say prayers for healing, or an ancient philosopher and physician would apply bloodletting according to the theories of humorism. In recent centuries, since the advent of modern science, most medicine has become a combination of art and science (both basic and applied, under the umbrella of medical science). While stitching technique for sutures is an art learned through practice, the knowledge of what happens at the cellular and molecular level in the tissues being stitched arises through science.

Prescientific forms of medicine are now known as traditional medicine or folk medicine, which remains commonly used in the absence of scientific medicine, and are thus called alternative medicine. Alternative treatments outside of scientific medicine having safety and efficacy concerns are termed quackery.

Clinical practice

Medical availability and clinical practice varies across the world

due to regional differences in culture and technology. Modern scientific

medicine is highly developed in the Western world, while in developing countries such as parts of Africa or Asia, the population may rely more heavily on traditional medicine with limited evidence and efficacy and no required formal training for practitioners.

In the developed world, evidence-based medicine

is not universally used in clinical practice; for example, a 2007

survey of literature reviews found that about 49% of the interventions

lacked sufficient evidence to support either benefit or harm.

In modern clinical practice, physicians and physician assistants personally assess patients in order to diagnose, prognose, treat, and prevent disease using clinical judgment. The doctor-patient relationship typically begins an interaction with an examination of the patient's medical history and medical record, followed by a medical interview and a physical examination. Basic diagnostic medical devices (e.g. stethoscope, tongue depressor) are typically used. After examination for signs and interviewing for symptoms, the doctor may order medical tests (e.g. blood tests), take a biopsy, or prescribe pharmaceutical drugs or other therapies. Differential diagnosis

methods help to rule out conditions based on the information provided.

During the encounter, properly informing the patient of all relevant

facts is an important part of the relationship and the development of

trust. The medical encounter is then documented in the medical record,

which is a legal document in many jurisdictions.

Follow-ups may be shorter but follow the same general procedure, and

specialists follow a similar process. The diagnosis and treatment may

take only a few minutes or a few weeks depending upon the complexity of

the issue.

The components of the medical interview and encounter are:

- Chief complaint (CC): the reason for the current medical visit. These are the 'symptoms.'

They are in the patient's own words and are recorded along with the

duration of each one. Also called 'chief concern' or 'presenting

complaint'.

- History of present illness

(HPI): the chronological order of events of symptoms and further

clarification of each symptom. Distinguishable from history of previous

illness, often called past medical history (PMH). Medical history comprises HPI and PMH.

- Current activity: occupation, hobbies, what the patient actually does.

- Medications (Rx): what drugs the patient takes including prescribed, over-the-counter, and home remedies, as well as alternative and herbal medicines or remedies. Allergies are also recorded.

- Past medical history (PMH/PMHx): concurrent medical problems, past hospitalizations and operations, injuries, past infectious diseases or vaccinations, history of known allergies.

- Social history (SH): birthplace, residences, marital history, social and economic status, habits (including diet, medications, tobacco, alcohol).

- Family history (FH): listing of diseases in the family that may impact the patient. A family tree is sometimes used.

- Review of systems (ROS) or systems inquiry: a set of additional questions to ask, which may be missed on HPI: a general enquiry (have you noticed any weight loss, change in sleep quality, fevers, lumps and bumps? etc.), followed by questions on the body's main organ systems (heart, lungs, digestive tract, urinary tract, etc.).

The physical examination is the examination of the patient for medical signs

of disease, which are objective and observable, in contrast to symptoms

that are volunteered by the patient and not necessarily objectively

observable. The healthcare provider uses sight, hearing, touch, and sometimes smell (e.g., in infection, uremia, diabetic ketoacidosis). Four actions are the basis of physical examination: inspection, palpation (feel), percussion (tap to determine resonance characteristics), and auscultation (listen), generally in that order although auscultation occurs prior to percussion and palpation for abdominal assessments.

The clinical examination involves the study of:

- Vital signs including height, weight, body temperature, blood pressure, pulse, respiration rate, and hemoglobin oxygen saturation

- General appearance of the patient and specific indicators of disease (nutritional status, presence of jaundice, pallor or clubbing)

- Skin

- Head, eye, ear, nose, and throat (HEENT)

- Cardiovascular (heart and blood vessels)

- Respiratory (large airways and lungs)

- Abdomen and rectum

- Genitalia (and pregnancy if the patient is or could be pregnant)

- Musculoskeletal (including spine and extremities)

- Neurological (consciousness, awareness, brain, vision, cranial nerves, spinal cord and peripheral nerves)

- Psychiatric (orientation, mental state, mood, evidence of abnormal perception or thought).

It is to likely focus on areas of interest highlighted in the medical history and may not include everything listed above.

The treatment plan may include ordering additional medical laboratory tests and medical imaging studies, starting therapy, referral to a specialist, or watchful observation. Follow-up may be advised. Depending upon the health insurance plan and the managed care system, various forms of "utilization review", such as prior authorization of tests, may place barriers on accessing expensive services.

The medical decision-making (MDM) process involves analysis and

synthesis of all the above data to come up with a list of possible

diagnoses (the differential diagnoses), along with an idea of what needs to be done to obtain a definitive diagnosis that would explain the patient's problem.

On subsequent visits, the process may be repeated in an

abbreviated manner to obtain any new history, symptoms, physical

findings, and lab or imaging results or specialist consultations.

Institutions

Contemporary medicine is in general conducted within health care systems. Legal, credentialing

and financing frameworks are established by individual governments,

augmented on occasion by international organizations, such as churches.

The characteristics of any given health care system have significant

impact on the way medical care is provided.

From ancient times, Christian emphasis on practical charity gave

rise to the development of systematic nursing and hospitals and the Catholic Church today remains the largest non-government provider of medical services in the world. Advanced industrial countries (with the exception of the United States) and many developing countries provide medical services through a system of universal health care that aims to guarantee care for all through a single-payer health care system, or compulsory private or co-operative health insurance.

This is intended to ensure that the entire population has access to

medical care on the basis of need rather than ability to pay. Delivery

may be via private medical practices or by state-owned hospitals and

clinics, or by charities, most commonly by a combination of all three.

Most tribal

societies provide no guarantee of healthcare for the population as a

whole. In such societies, healthcare is available to those that can

afford to pay for it or have self-insured it (either directly or as part

of an employment contract) or who may be covered by care financed by

the government or tribe directly.

Transparency of information is another factor defining a delivery

system. Access to information on conditions, treatments, quality, and

pricing greatly affects the choice by patients/consumers and, therefore,

the incentives of medical professionals. While the US healthcare system

has come under fire for lack of openness,

new legislation may encourage greater openness. There is a perceived

tension between the need for transparency on the one hand and such

issues as patient confidentiality and the possible exploitation of

information for commercial gain on the other.

Delivery

Provision of medical care is classified into primary, secondary, and tertiary care categories.

Primary care medical services are provided by physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, or other health professionals who have first contact with a patient seeking medical treatment or care. These occur in physician offices, clinics, nursing homes,

schools, home visits, and other places close to patients. About 90% of

medical visits can be treated by the primary care provider. These

include treatment of acute and chronic illnesses, preventive care and health education for all ages and both sexes.

Secondary care medical services are provided by medical specialists

in their offices or clinics or at local community hospitals for a

patient referred by a primary care provider who first diagnosed or

treated the patient. Referrals are made for those patients who required the expertise or procedures performed by specialists. These include both ambulatory care and inpatient services, Emergency departments, intensive care medicine, surgery services, physical therapy, labor and delivery, endoscopy units, diagnostic laboratory and medical imaging services, hospice

centers, etc. Some primary care providers may also take care of

hospitalized patients and deliver babies in a secondary care setting.

Tertiary care

medical services are provided by specialist hospitals or regional

centers equipped with diagnostic and treatment facilities not generally

available at local hospitals. These include trauma centers, burn treatment centers, advanced neonatology unit services, organ transplants, high-risk pregnancy, radiation oncology, etc.

Modern medical care also depends on information – still delivered

in many health care settings on paper records, but increasingly

nowadays by electronic means.

In low-income countries, modern healthcare is often too expensive

for the average person. International healthcare policy researchers

have advocated that "user fees" be removed in these areas to ensure

access, although even after removal, significant costs and barriers

remain.

Separation of prescribing and dispensing is a practice in medicine and pharmacy in which the physician who provides a medical prescription is independent from the pharmacist who provides the prescription drug. In the Western world

there are centuries of tradition for separating pharmacists from

physicians. In Asian countries, it is traditional for physicians to also

provide drugs.

Branches

Drawing by

Marguerite Martyn (1918) of a visiting nurse in St. Louis, Missouri, with medicine and babies

Working together as an interdisciplinary team, many highly trained health professionals besides medical practitioners are involved in the delivery of modern health care. Examples include: nurses, emergency medical technicians and paramedics, laboratory scientists, pharmacists, podiatrists, physiotherapists, respiratory therapists, speech therapists, occupational therapists, radiographers, dietitians, and bioengineers, medical physics, surgeons, surgeon's assistant, surgical technologist.

The scope and sciences underpinning human medicine overlap many other fields. Dentistry, while considered by some a separate discipline from medicine, is a medical field.

A patient admitted to the hospital is usually under the care of a

specific team based on their main presenting problem, e.g., the

cardiology team, who then may interact with other specialties, e.g.,

surgical, radiology, to help diagnose or treat the main problem or any

subsequent complications/developments.

Physicians have many specializations and subspecializations into

certain branches of medicine, which are listed below. There are

variations from country to country regarding which specialties certain

subspecialties are in.

The main branches of medicine are:

Basic sciences

- Anatomy is the study of the physical structure of organisms. In contrast to macroscopic or gross anatomy, cytology and histology are concerned with microscopic structures.

- Biochemistry

is the study of the chemistry taking place in living organisms,

especially the structure and function of their chemical components.

- Biomechanics is the study of the structure and function of biological systems by means of the methods of Mechanics.

- Biostatistics

is the application of statistics to biological fields in the broadest

sense. A knowledge of biostatistics is essential in the planning,

evaluation, and interpretation of medical research. It is also

fundamental to epidemiology and evidence-based medicine.

- Biophysics is an interdisciplinary science that uses the methods of physics and physical chemistry to study biological systems.

- Cytology is the microscopic study of individual cells.

- Embryology is the study of the early development of organisms.

- Endocrinology is the study of hormones and their effect throughout the body of animals.

- Epidemiology is the study of the demographics of disease processes, and includes, but is not limited to, the study of epidemics.

- Genetics is the study of genes, and their role in biological inheritance.

- Histology is the study of the structures of biological tissues by light microscopy, electron microscopy and immunohistochemistry.

- Immunology is the study of the immune system, which includes the innate and adaptive immune system in humans, for example.

- Medical physics is the study of the applications of physics principles in medicine.

- Microbiology is the study of microorganisms, including protozoa, bacteria, fungi, and viruses.

- Molecular biology is the study of molecular underpinnings of the process of replication, transcription and translation of the genetic material.

- Neuroscience includes those disciplines of science that are related to the study of the nervous system. A main focus of neuroscience is the biology and physiology of the human brain and spinal cord. Some related clinical specialties include neurology, neurosurgery and psychiatry.

- Nutrition science (theoretical focus) and dietetics

(practical focus) is the study of the relationship of food and drink to

health and disease, especially in determining an optimal diet. Medical

nutrition therapy is done by dietitians and is prescribed for diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, weight and eating disorders, allergies, malnutrition, and neoplastic diseases.

- Pathology as a science is the study of disease—the causes, course, progression and resolution thereof.

- Pharmacology is the study of drugs and their actions.

- Gynecology is the study of female reproductive system.

- Photobiology is the study of the interactions between non-ionizing radiation and living organisms.

- Physiology is the study of the normal functioning of the body and the underlying regulatory mechanisms.

- Radiobiology is the study of the interactions between ionizing radiation and living organisms.

- Toxicology is the study of hazardous effects of drugs and poisons.

Specialties

In the broadest meaning of "medicine", there are many different

specialties. In the UK, most specialities have their own body or

college, which has its own entrance examination. These are collectively

known as the Royal Colleges, although not all currently use the term

"Royal". The development of a speciality is often driven by new

technology (such as the development of effective anaesthetics) or ways

of working (such as emergency departments); the new specialty leads to

the formation of a unifying body of doctors and the prestige of

administering their own examination.

Within medical circles, specialities usually fit into one of two

broad categories: "Medicine" and "Surgery." "Medicine" refers to the

practice of non-operative medicine, and most of its subspecialties

require preliminary training in Internal Medicine. In the UK, this was

traditionally evidenced by passing the examination for the Membership of

the Royal College of Physicians

(MRCP) or the equivalent college in Scotland or Ireland. "Surgery"

refers to the practice of operative medicine, and most subspecialties in

this area require preliminary training in General Surgery, which in the

UK leads to membership of the Royal College of Surgeons of England

(MRCS). At present, some specialties of medicine do not fit easily into

either of these categories, such as radiology, pathology, or

anesthesia. Most of these have branched from one or other of the two

camps above; for example anaesthesia developed first as a faculty of the Royal College of Surgeons (for which MRCS/FRCS would have been required) before becoming the Royal College of Anaesthetists

and membership of the college is attained by sitting for the

examination of the Fellowship of the Royal College of Anesthetists

(FRCA).

Surgical specialty

Surgery is an ancient medical specialty that uses operative manual and instrumental techniques on a patient to investigate or treat a pathological condition such as disease or injury, to help improve bodily function or appearance or to repair unwanted ruptured areas (for example, a perforated ear drum).

Surgeons must also manage pre-operative, post-operative, and potential

surgical candidates on the hospital wards. Surgery has many

sub-specialties, including general surgery, ophthalmic surgery, cardiovascular surgery, colorectal surgery, neurosurgery, oral and maxillofacial surgery, oncologic surgery, orthopedic surgery, otolaryngology, plastic surgery, podiatric surgery, transplant surgery, trauma surgery, urology, vascular surgery, and pediatric surgery. In some centers, anesthesiology

is part of the division of surgery (for historical and logistical

reasons), although it is not a surgical discipline. Other medical

specialties may employ surgical procedures, such as ophthalmology and dermatology, but are not considered surgical sub-specialties per se.

Surgical training in the U.S. requires a minimum of five years of

residency after medical school. Sub-specialties of surgery often

require seven or more years. In addition, fellowships can last an

additional one to three years. Because post-residency fellowships can be

competitive, many trainees devote two additional years to research.

Thus in some cases surgical training will not finish until more than a

decade after medical school. Furthermore, surgical training can be very

difficult and time-consuming.

Internal medicine specialty

Internal medicine is the medical specialty dealing with the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of adult diseases. According to some sources, an emphasis on internal structures is implied. In North America, specialists in internal medicine are commonly called "internists." Elsewhere, especially in Commonwealth nations, such specialists are often called physicians. These terms, internist or physician

(in the narrow sense, common outside North America), generally exclude

practitioners of gynecology and obstetrics, pathology, psychiatry, and

especially surgery and its subspecialities.

Because their patients are often seriously ill or require complex

investigations, internists do much of their work in hospitals.

Formerly, many internists were not subspecialized; such general physicians

would see any complex nonsurgical problem; this style of practice has

become much less common. In modern urban practice, most internists are

subspecialists: that is, they generally limit their medical practice to

problems of one organ system or to one particular area of medical

knowledge. For example, gastroenterologists and nephrologists specialize respectively in diseases of the gut and the kidneys.

In the Commonwealth of Nations and some other countries, specialist pediatricians and geriatricians are also described as specialist physicians

(or internists) who have subspecialized by age of patient rather than

by organ system. Elsewhere, especially in North America, general

pediatrics is often a form of primary care.

There are many subspecialities (or subdisciplines) of internal medicine:

Training in internal medicine (as opposed to surgical training), varies considerably across the world: see the articles on medical education and physician

for more details. In North America, it requires at least three years of

residency training after medical school, which can then be followed by a

one- to three-year fellowship in the subspecialties listed above. In

general, resident work hours in medicine are less than those in surgery,

averaging about 60 hours per week in the US. This difference does not

apply in the UK where all doctors are now required by law to work less

than 48 hours per week on average.

Diagnostic specialties

- Clinical laboratory sciences

are the clinical diagnostic services that apply laboratory techniques

to diagnosis and management of patients. In the United States, these

services are supervised by a pathologist. The personnel that work in

these medical laboratory departments are technically trained staff who do not hold medical degrees, but who usually hold an undergraduate medical technology degree, who actually perform the tests, assays, and procedures needed for providing the specific services. Subspecialties include transfusion medicine, cellular pathology, clinical chemistry, hematology, clinical microbiology and clinical immunology.

- Pathology as a medical specialty

is the branch of medicine that deals with the study of diseases and the

morphologic, physiologic changes produced by them. As a diagnostic

specialty, pathology can be considered the basis of modern scientific

medical knowledge and plays a large role in evidence-based medicine. Many modern molecular tests such as flow cytometry, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), immunohistochemistry, cytogenetics, gene rearrangements studies and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) fall within the territory of pathology.

- Diagnostic radiology is concerned with imaging of the body, e.g. by x-rays, x-ray computed tomography, ultrasonography, and nuclear magnetic resonance tomography. Interventional radiologists can access areas in the body under imaging for an intervention or diagnostic sampling.

- Nuclear medicine

is concerned with studying human organ systems by administering

radiolabelled substances (radiopharmaceuticals) to the body, which can

then be imaged outside the body by a gamma camera

or a PET scanner. Each radiopharmaceutical consists of two parts: a

tracer that is specific for the function under study (e.g.,

neurotransmitter pathway, metabolic pathway, blood flow, or other), and a

radionuclide (usually either a gamma-emitter or a positron emitter).

There is a degree of overlap between nuclear medicine and radiology, as

evidenced by the emergence of combined devices such as the PET/CT

scanner.

- Clinical neurophysiology

is concerned with testing the physiology or function of the central and

peripheral aspects of the nervous system. These kinds of tests can be

divided into recordings of: (1) spontaneous or continuously running

electrical activity, or (2) stimulus evoked responses. Subspecialties

include electroencephalography, electromyography, evoked potential, nerve conduction study and polysomnography.

Sometimes these tests are performed by techs without a medical degree,

but the interpretation of these tests is done by a medical professional.

Other major specialties

The following are some major medical specialties that do not directly fit into any of the above-mentioned groups:

- Anesthesiology (also known as anaesthetics):

concerned with the perioperative management of the surgical patient.

The anesthesiologist's role during surgery is to prevent derangement in

the vital organs' (i.e. brain, heart, kidneys) functions and

postoperative pain. Outside of the operating room, the anesthesiology

physician also serves the same function in the labor and delivery ward,

and some are specialized in critical medicine.

- Dermatology is concerned with the skin and its diseases. In the UK, dermatology is a subspecialty of general medicine.

- Emergency medicine is concerned with the diagnosis and treatment of acute or life-threatening conditions, including trauma, surgical, medical, pediatric, and psychiatric emergencies.

- Family medicine, family practice, general practice or primary care

is, in many countries, the first port-of-call for patients with

non-emergency medical problems. Family physicians often provide services

across a broad range of settings including office based practices,

emergency department coverage, inpatient care, and nursing home care.

- Obstetrics and gynecology (often abbreviated as OB/GYN (American English) or Obs & Gynae (British English)) are concerned respectively with childbirth and the female reproductive and associated organs. Reproductive medicine and fertility medicine are generally practiced by gynecological specialists.

- Medical genetics is concerned with the diagnosis and management of hereditary disorders.

- Neurology is concerned with diseases of the nervous system. In the UK, neurology is a subspecialty of general medicine.

- Ophthalmology is exclusively concerned with the eye and ocular adnexa, combining conservative and surgical therapy.

- Pediatrics (AE) or paediatrics

(BE) is devoted to the care of infants, children, and adolescents. Like

internal medicine, there are many pediatric subspecialties for specific

age ranges, organ systems, disease classes, and sites of care delivery.

- Pharmaceutical medicine

is the medical scientific discipline concerned with the discovery,

development, evaluation, registration, monitoring and medical aspects of

marketing of medicines for the benefit of patients and public health.

- Physical medicine and rehabilitation (or physiatry) is concerned with functional improvement after injury, illness, or congenital disorders.

- Podiatric medicine

is the study of, diagnosis, and medical & surgical treatment of

disorders of the foot, ankle, lower limb, hip and lower back.

- Psychiatry is the branch of medicine concerned with the bio-psycho-social study of the etiology, diagnosis, treatment and prevention of cognitive, perceptual, emotional and behavioral disorders. Related fields include psychotherapy and clinical psychology.

- Preventive medicine is the branch of medicine concerned with preventing disease.

Interdisciplinary fields

Some interdisciplinary sub-specialties of medicine include:

- Aerospace medicine deals with medical problems related to flying and space travel.

- Addiction medicine deals with the treatment of addiction.

- Medical ethics deals with ethical and moral principles that apply values and judgments to the practice of medicine.

- Biomedical Engineering is a field dealing with the application of engineering principles to medical practice.

- Clinical pharmacology is concerned with how systems of therapeutics interact with patients.

- Conservation medicine studies the relationship between human and animal health, and environmental conditions. Also known as ecological medicine, environmental medicine, or medical geology.

- Disaster medicine deals with medical aspects of emergency preparedness, disaster mitigation and management.

- Diving medicine (or hyperbaric medicine) is the prevention and treatment of diving-related problems.

- Evolutionary medicine is a perspective on medicine derived through applying evolutionary theory.

- Forensic medicine deals with medical questions in legal

context, such as determination of the time and cause of death, type of

weapon used to inflict trauma, reconstruction of the facial features

using remains of deceased (skull) thus aiding identification.

- Gender-based medicine studies the biological and physiological differences between the human sexes and how that affects differences in disease.

- Hospice and Palliative Medicine

is a relatively modern branch of clinical medicine that deals with pain

and symptom relief and emotional support in patients with terminal illnesses including cancer and heart failure.

- Hospital medicine

is the general medical care of hospitalized patients. Physicians whose

primary professional focus is hospital medicine are called hospitalists in the United States and Canada. The term Most Responsible Physician (MRP) or attending physician is also used interchangeably to describe this role.

- Laser medicine involves the use of lasers in the diagnostics or treatment of various conditions.

- Medical humanities includes the humanities (literature, philosophy, ethics, history and religion), social science (anthropology, cultural studies, psychology, sociology), and the arts (literature, theater, film, and visual arts) and their application to medical education and practice.

- Health informatics is a relatively recent field that deal with the application of computers and information technology to medicine.

- Nosology is the classification of diseases for various purposes.

- Nosokinetics is the science/subject of measuring and modelling the process of care in health and social care systems.

- Occupational medicine

is the provision of health advice to organizations and individuals to

ensure that the highest standards of health and safety at work can be

achieved and maintained.

- Pain management (also called pain medicine, or algiatry) is the medical discipline concerned with the relief of pain.

- Pharmacogenomics is a form of individualized medicine.

- Podiatric medicine is the study of, diagnosis, and medical treatment of disorders of the foot, ankle, lower limb, hip and lower back.

- Sexual medicine is concerned with diagnosing, assessing and treating all disorders related to sexuality.

- Sports medicine deals with the treatment and prevention and rehabilitation of sports/exercise injuries such as muscle spasms, muscle tears, injuries to ligaments (ligament tears or ruptures) and their repair in athletes, amateur and professional.

- Therapeutics

is the field, more commonly referenced in earlier periods of history,

of the various remedies that can be used to treat disease and promote

health.

- Travel medicine or emporiatrics deals with health problems of international travelers or travelers across highly different environments.

- Tropical medicine

deals with the prevention and treatment of tropical diseases. It is

studied separately in temperate climates where those diseases are quite

unfamiliar to medical practitioners and their local clinical needs.

- Urgent care

focuses on delivery of unscheduled, walk-in care outside of the

hospital emergency department for injuries and illnesses that are not

severe enough to require care in an emergency department. In some

jurisdictions this function is combined with the emergency department.

- Veterinary medicine; veterinarians apply similar techniques as physicians to the care of animals.

- Wilderness medicine entails the practice of medicine in the wild, where conventional medical facilities may not be available.

- Many other health science fields, e.g. dietetics

Education and legal controls

Medical students learning about stitches

Medical education and training varies around the world. It typically involves entry level education at a university medical school, followed by a period of supervised practice or internship, or residency.

This can be followed by postgraduate vocational training. A variety of

teaching methods have been employed in medical education, still itself a

focus of active research. In Canada and the United States of America, a

Doctor of Medicine degree, often abbreviated M.D., or a Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine

degree, often abbreviated as D.O. and unique to the United States, must

be completed in and delivered from a recognized university.

Since knowledge, techniques, and medical technology continue to evolve at a rapid rate, many regulatory authorities require continuing medical education. Medical practitioners upgrade their knowledge in various ways, including medical journals,

seminars, conferences, and online programs. A database of objectives

covering medical knowledge, as suggested by national societies across

the United States, can be searched at http://data.medobjectives.marian.edu/.

In most countries, it is a legal requirement for a medical doctor to

be licensed or registered. In general, this entails a medical degree

from a university and accreditation by a medical board or an equivalent

national organization, which may ask the applicant to pass exams. This

restricts the considerable legal authority of the medical profession to

physicians that are trained and qualified by national standards. It is

also intended as an assurance to patients and as a safeguard against charlatans

that practice inadequate medicine for personal gain. While the laws

generally require medical doctors to be trained in "evidence based",

Western, or Hippocratic Medicine, they are not intended to discourage different paradigms of health.

In the European Union, the profession of doctor of medicine is

regulated. A profession is said to be regulated when access and exercise

is subject to the possession of a specific professional qualification.

The regulated professions database contains a list of regulated

professions for doctor of medicine in the EU member states, EEA

countries and Switzerland. This list is covered by the Directive

2005/36/EC.

Doctors who are negligent or intentionally harmful in their care of patients can face charges of medical malpractice and be subject to civil, criminal, or professional sanctions.

Medical ethics

Medical ethics is a system of moral principles that apply values and

judgments to the practice of medicine. As a scholarly discipline,

medical ethics encompasses its practical application in clinical

settings as well as work on its history, philosophy, theology, and

sociology. Six of the values that commonly apply to medical ethics

discussions are:

- autonomy – the patient has the right to refuse or choose their treatment. (Voluntas aegroti suprema lex.)

- beneficence – a practitioner should act in the best interest of the patient. (Salus aegroti suprema lex.)

- justice – concerns the distribution of scarce health resources, and the decision of who gets what treatment (fairness and equality).

- non-maleficence – "first, do no harm" (primum non-nocere).

- respect for persons – the patient (and the person treating the patient) have the right to be treated with dignity.

- truthfulness and honesty – the concept of informed consent has increased in importance since the historical events of the Doctors' Trial of the Nuremberg trials, Tuskegee syphilis experiment, and others.

Values such as these do not give answers as to how to handle a

particular situation, but provide a useful framework for understanding

conflicts. When moral values are in conflict, the result may be an

ethical dilemma

or crisis. Sometimes, no good solution to a dilemma in medical ethics

exists, and occasionally, the values of the medical community (i.e., the

hospital and its staff) conflict with the values of the individual

patient, family, or larger non-medical community. Conflicts can also

arise between health care providers, or among family members. For

example, some argue that the principles of autonomy and beneficence

clash when patients refuse blood transfusions, considering them life-saving; and truth-telling was not emphasized to a large extent before the HIV era.

History

Statuette of ancient Egyptian physician

Imhotep, the first physician from antiquity known by name

Ancient world

Prehistoric medicine incorporated plants (herbalism), animal parts, and minerals. In many cases these materials were used ritually as magical substances by priests, shamans, or medicine men. Well-known spiritual systems include animism (the notion of inanimate objects having spirits), spiritualism (an appeal to gods or communion with ancestor spirits); shamanism (the vesting of an individual with mystic powers); and divination (magically obtaining the truth). The field of medical anthropology

examines the ways in which culture and society are organized around or

impacted by issues of health, health care and related issues.

Early records on medicine have been discovered from ancient Egyptian medicine, Babylonian Medicine, Ayurvedic medicine (in the Indian subcontinent), classical Chinese medicine (predecessor to the modern traditional Chinese medicine), and ancient Greek medicine and Roman medicine.

In Egypt, Imhotep (3rd millennium BCE) is the first physician in history known by name. The oldest Egyptian medical text is the Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus from around 2000 BCE, which describes gynaecological diseases. The Edwin Smith Papyrus dating back to 1600 BCE is an early work on surgery, while the Ebers Papyrus dating back to 1500 BCE is akin to a textbook on medicine.

In China, archaeological evidence of medicine in Chinese dates back to the Bronze Age Shang Dynasty, based on seeds for herbalism and tools presumed to have been used for surgery. The Huangdi Neijing,

the progenitor of Chinese medicine, is a medical text written beginning

in the 2nd century BCE and compiled in the 3rd century.

In India, the surgeon Sushruta described numerous surgical operations, including the earliest forms of plastic surgery. Earliest records of dedicated hospitals come from Mihintale in Sri Lanka where evidence of dedicated medicinal treatment facilities for patients are found.

In Greece, the Greek physician Hippocrates, the "father of modern medicine", laid the foundation for a rational approach to medicine. Hippocrates introduced the Hippocratic Oath for physicians, which is still relevant and in use today, and was the first to categorize illnesses as acute, chronic, endemic and epidemic, and use terms such as, "exacerbation, relapse, resolution, crisis, paroxysm, peak, and convalescence". The Greek physician Galen

was also one of the greatest surgeons of the ancient world and

performed many audacious operations, including brain and eye surgeries.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the onset of the Early Middle Ages, the Greek tradition of medicine went into decline in Western Europe, although it continued uninterrupted in the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire.

Most of our knowledge of ancient Hebrew medicine during the 1st millennium BC comes from the Torah, i.e. the Five Books of Moses,

which contain various health related laws and rituals. The Hebrew

contribution to the development of modern medicine started in the Byzantine Era, with the physician Asaph the Jew.

Middle Ages

The concept of hospital as institution to offer medical care and

possibility of a cure for the patients due to the ideals of Christian

charity, rather than just merely a place to die, appeared in the Byzantine Empire.

Although the concept of uroscopy

was known to Galen, he did not see the importance of using it to

localize the disease. It was under the Byzantines with physicians such

of Theophilus Protospatharius

that they realized the potential in uroscopy to determine disease in a

time when no microscope or stethoscope existed. That practice eventually

spread to the rest of Europe.

After 750 CE, the Muslim world had the works of Hippocrates, Galen and Sushruta translated into Arabic, and Islamic physicians engaged in some significant medical research. Notable Islamic medical pioneers include the Persian polymath, Avicenna, who, along with Imhotep and Hippocrates, has also been called the "father of medicine". He wrote The Canon of Medicine which became a standard medical text at many medieval European universities, considered one of the most famous books in the history of medicine. Others include Abulcasis, Avenzoar, Ibn al-Nafis, and Averroes. Persian physician Rhazes was one of the first to question the Greek theory of humorism, which nevertheless remained influential in both medieval Western and medieval Islamic medicine. Some volumes of Rhazes's work Al-Mansuri, namely "On Surgery" and "A General Book on Therapy", became part of the medical curriculum in European universities. Additionally, he has been described as a doctor's doctor, the father of pediatrics, and a pioneer of ophthalmology. For example, he was the first to recognize the reaction of the eye's pupil to light. The Persian Bimaristan hospitals were an early example of public hospitals.

In Europe, Charlemagne decreed that a hospital should be attached to each cathedral and monastery and the historian Geoffrey Blainey likened the activities of the Catholic Church in health care

during the Middle Ages to an early version of a welfare state: "It

conducted hospitals for the old and orphanages for the young; hospices

for the sick of all ages; places for the lepers; and hostels or inns

where pilgrims could buy a cheap bed and meal". It supplied food to the

population during famine and distributed food to the poor. This welfare

system the church funded through collecting taxes on a large scale and

possessing large farmlands and estates. The Benedictine

order was noted for setting up hospitals and infirmaries in their

monasteries, growing medical herbs and becoming the chief medical care

givers of their districts, as at the great Abbey of Cluny. The Church also established a network of cathedral schools and universities where medicine was studied. The Schola Medica Salernitana in Salerno, looking to the learning of Greek and Arab physicians, grew to be the finest medical school in Medieval Europe.

Siena's

Santa Maria della Scala Hospital,

one of Europe's oldest hospitals. During the Middle Ages, the Catholic

Church established universities to revive the study of sciences, drawing

on the learning of Greek and Arab physicians in the study of medicine.

However, the fourteenth and fifteenth century Black Death

devastated both the Middle East and Europe, and it has even been argued

that Western Europe was generally more effective in recovering from the

pandemic than the Middle East. In the early modern period, important early figures in medicine and anatomy emerged in Europe, including Gabriele Falloppio and William Harvey.

The major shift in medical thinking was the gradual rejection, especially during the Black Death

in the 14th and 15th centuries, of what may be called the 'traditional

authority' approach to science and medicine. This was the notion that

because some prominent person in the past said something must be so,

then that was the way it was, and anything one observed to the contrary

was an anomaly (which was paralleled by a similar shift in European

society in general – see Copernicus's rejection of Ptolemy's theories on astronomy). Physicians like Vesalius

improved upon or disproved some of the theories from the past. The main

tomes used both by medicine students and expert physicians were Materia Medica and Pharmacopoeia.

Andreas Vesalius was the author of De humani corporis fabrica, an important book on human anatomy. Bacteria and microorganisms were first observed with a microscope by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek in 1676, initiating the scientific field microbiology. Independently from Ibn al-Nafis, Michael Servetus rediscovered the pulmonary circulation, but this discovery did not reach the public because it was written down for the first time in the "Manuscript of Paris" in 1546, and later published in the theological work for which he paid with his life in 1553. Later this was described by Renaldus Columbus and Andrea Cesalpino. Herman Boerhaave

is sometimes referred to as a "father of physiology" due to his

exemplary teaching in Leiden and textbook 'Institutiones medicae'

(1708). Pierre Fauchard has been called "the father of modern dentistry".

Modern

Veterinary medicine was, for the first time, truly separated from human medicine in 1761, when the French veterinarian Claude Bourgelat

founded the world's first veterinary school in Lyon, France. Before

this, medical doctors treated both humans and other animals.

Modern scientific biomedical research (where results are testable and reproducible) began to replace early Western traditions based on herbalism, the Greek "four humours" and other such pre-modern notions. The modern era really began with Edward Jenner's discovery of the smallpox vaccine at the end of the 18th century (inspired by the method of inoculation earlier practiced in Asia), Robert Koch's discoveries around 1880 of the transmission of disease by bacteria, and then the discovery of antibiotics around 1900.

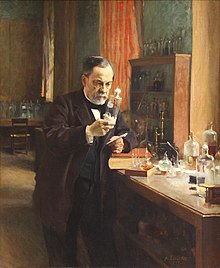

The post-18th century modernity period brought more groundbreaking researchers from Europe. From Germany and Austria, doctors Rudolf Virchow, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, Karl Landsteiner and Otto Loewi made notable contributions. In the United Kingdom, Alexander Fleming, Joseph Lister, Francis Crick and Florence Nightingale are considered important. Spanish doctor Santiago Ramón y Cajal is considered the father of modern neuroscience.

From New Zealand and Australia came Maurice Wilkins, Howard Florey, and Frank Macfarlane Burnet.

Others that did significant work include William Williams Keen, William Coley, James D. Watson (United States); Salvador Luria (Italy); Alexandre Yersin (Switzerland); Kitasato Shibasaburō (Japan); Jean-Martin Charcot, Claude Bernard, Paul Broca (France); Adolfo Lutz (Brazil); Nikolai Korotkov (Russia); Sir William Osler (Canada); and Harvey Cushing (United States).

Alexander Fleming's discovery of penicillin in September 1928 marks the start of modern antibiotics.

As science and technology developed, medicine became more reliant upon medications.

Throughout history and in Europe right until the late 18th century, not

only animal and plant products were used as medicine, but also human

body parts and fluids. Pharmacology developed in part from herbalism and some drugs are still derived from plants (atropine, ephedrine, warfarin, aspirin, digoxin, vinca alkaloids, taxol, hyoscine, etc.). Vaccines were discovered by Edward Jenner and Louis Pasteur.

The first antibiotic was arsphenamine (Salvarsan) discovered by Paul Ehrlich in 1908 after he observed that bacteria took up toxic dyes that human cells did not. The first major class of antibiotics was the sulfa drugs, derived by German chemists originally from azo dyes.

Pharmacology has become increasingly sophisticated; modern biotechnology

allows drugs targeted towards specific physiological processes to be

developed, sometimes designed for compatibility with the body to reduce side-effects. Genomics and knowledge of human genetics and human evolution is having increasingly significant influence on medicine, as the causative genes of most monogenic genetic disorders have now been identified, and the development of techniques in molecular biology, evolution, and genetics are influencing medical technology, practice and decision-making.

Evidence-based medicine is a contemporary movement to establish the most effective algorithms of practice (ways of doing things) through the use of systematic reviews and meta-analysis. The movement is facilitated by modern global information science,

which allows as much of the available evidence as possible to be

collected and analyzed according to standard protocols that are then

disseminated to healthcare providers. The Cochrane Collaboration

leads this movement. A 2001 review of 160 Cochrane systematic reviews

revealed that, according to two readers, 21.3% of the reviews concluded

insufficient evidence, 20% concluded evidence of no effect, and 22.5%

concluded positive effect.

Quality, efficiency, and access

Evidence-based medicine, prevention of medical error (and other "iatrogenesis"), and avoidance of unnecessary health care

are a priority in modern medical systems. These topics generate

significant political and public policy attention, particularly in the

United States where healthcare is regarded as excessively costly but population health metrics lag similar nations.

Globally, many developing countries lack access to care and access to medicines. As of 2015, most wealthy developed countries provide health care to all citizens, with a few exceptions such as the United States where lack of health insurance coverage may limit access.

Traditional medicine

The World Health Organization

(WHO) defines traditional medicine as "the sum total of the knowledge,

skills, and practices based on the theories, beliefs, and experiences

indigenous to different cultures, whether explicable or not, used in the

maintenance of health as well as in the prevention, diagnosis,

improvement or treatment of physical and mental illness." Practices known as traditional medicines include Ayurveda, Siddha medicine, Unani, ancient Iranian medicine, Irani, Islamic medicine, traditional Chinese medicine, traditional Korean medicine, acupuncture, Muti, Ifá, and traditional African medicine.

The WHO stated that "inappropriate use of traditional medicines

or practices can have negative or dangerous effects" and that "further

research is needed to ascertain the efficacy and safety" of several of

the practices and medicinal plants used by traditional medicine systems. As example, Indian Medical Association regard traditional medicine practices, such as Ayurveda and Siddha medicine, as quackery.

Practitioners of traditional medicine are not authorized to practice

medicine in India unless trained at a qualified medical institution,

registered with the government, and listed as registered physicians

annually in The Gazette of India.

Identifying practitioners of traditional medicine, the Supreme Court of

India stated in 2018 that "unqualified, untrained quacks are posing a

great risk to the entire society and playing with the lives of people

without having the requisite training and education in the science from

approved institutions".

Evidence on the effectiveness of the alternative medicine practice of acupuncture is "variable and inconsistent" for any condition, but is generally safe when done by an appropriately trained practitioner.