Discrimination is the act of making unjustified distinctions between human beings based on the groups, classes, or other categories to which they are perceived to belong. People may be discriminated on the basis of race, gender, age, religion, or sexual orientation, as well as other categories. Discrimination especially occurs when individuals or groups are unfairly treated in a way which is worse than other people are treated, on the basis of their actual or perceived membership in certain groups or social categories. It involves restricting members of one group from opportunities or privileges that are available to members of another group.

Discriminatory traditions, policies, ideas, practices and laws exist in many countries and institutions in all parts of the world, including territories where discrimination is generally looked down upon. In some places, attempts such as quotas have been used to benefit those who are believed to be current or past victims of discrimination. These attempts have often been met with controversy, and have sometimes been called reverse discrimination.

Etymology

The term discriminate appeared in the early 17th century in the English language. It is from the Latin discriminat- 'distinguished between', from the verb discriminare, from discrimen 'distinction', from the verb discernere. Since the American Civil War the term "discrimination" generally evolved in American English usage as an understanding of prejudicial treatment of an individual based solely on their race, later generalized as membership in a certain socially undesirable group or social category. Before this sense of the word became almost universal, it was a synonym for discernment, tact and culture as in "taste and discrimination", generally a laudable attribute; to "discriminate against" being commonly disparaged.

Definitions

Moral philosophers have defined discrimination using a normative definition. Under this normative approach, discrimination is defined as wrongfully imposed disadvantageous treatment or consideration. This is also a comparative definition. An individual need not be actually harmed in order to be discriminated against. They just need to be treated worse than others for some arbitrary reason. If someone decides to donate to help orphan children, but decides to donate less, say, to black children out of a racist attitude, then they would be acting in a discriminatory way despite the fact that the people they discriminate against actually benefit by receiving a donation. In addition to this discrimination develops into a source of oppression. It is similar to the action of recognizing someone as 'different' so much that they are treated inhumanly and degraded. This normative definition of discrimination is distinct to a descriptive definition - in the former, discrimination is wrong by definition, whereas in the latter, discrimination is only morally wrong in a given context.

The United Nations stance on discrimination includes the statement: "Discriminatory behaviors take many forms, but they all involve some form of exclusion or rejection." International bodies United Nations Human Rights Council work towards helping ending discrimination around the world.

Types of discrimination

Age

Ageism or age discrimination is discrimination and stereotyping based on the grounds of someone's age. It is a set of beliefs, norms, and values which used to justify discrimination or subordination based on a person's age. Ageism is most often directed toward elderly people, or adolescents and children.

Age discrimination in hiring has been shown to exist in the United States. Joanna Lahey, professor at The Bush School of Government and Public Service at Texas A&M, found that firms are more than 40% more likely to interview a young adult job applicant than an older job applicant. In Europe, Stijn Baert, Jennifer Norga, Yannick Thuy and Marieke Van Hecke, researchers at Ghent University, measured comparable ratios in Belgium. They found that age discrimination is heterogeneous by the activity older candidates undertook during their additional post-educational years. In Belgium, they are only discriminated if they have more years of inactivity or irrelevant employment.

In a survey for the University of Kent, England, 29% of respondents stated that they had suffered from age discrimination. This is a higher proportion than for gender or racial discrimination. Dominic Abrams, social psychology professor at the university, concluded that ageism is the most pervasive form of prejudice experienced in the UK population.

Caste

According to UNICEF and Human Rights Watch, caste discrimination affects an estimated 250 million people worldwide and is mainly prevalent in parts of Asia (India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Nepal, Japan) and Africa. As of 2011, there were 200 million Dalits or Scheduled Castes (formerly known as "untouchables") in India.

Disability

Discrimination against people with disabilities in favor of people who are not is called ableism or disablism. Disability discrimination, which treats non-disabled individuals as the standard of 'normal living', results in public and private places and services, educational settings, and social services that are built to serve 'standard' people, thereby excluding those with various disabilities. Studies have shown that disabled people not only need employment in order to be provided with the opportunity to earn a living but they also need employment in order to sustain their mental health and well-being. Work fulfils a number of basic needs for an individual such as collective purpose, social contact, status, and activity. A person with a disability is often found to be socially isolated and work is one way to reduce his or her isolation.

In the United States, the Americans with Disabilities Act mandates the provision of equality of access to both buildings and services and is paralleled by similar acts in other countries, such as the Equality Act 2010 in the UK.

Language

Diversity of language is protected and respected by many nations which value cultural diversity. However, people are sometimes subjected to different treatment because their preferred language is associated with a particular group, class or category. Notable examples are the Anti-French sentiment in the United States as well as the Anti-Quebec sentiment in Canada targeting people who speak the French language. Commonly, the preferred language is just another attribute of separate ethnic groups. Discrimination exists if there is prejudicial treatment against a person or a group of people who either do or do not speak a particular language or languages. An example of this is when thousands of Wayúu Native Colombians were given derisive names and the same birth date, by government officials, during a campaign to provide them with identification cards. The issue was not discovered until many years later.

Another noteworthy example of linguistic discrimination is the backdrop to the Bengali Language Movement in erstwhile Pakistan, a political campaign that played a key role in the creation of Bangladesh. In 1948, Mohammad Ali Jinnah declared Urdu as the national language of Pakistan and branded those supporting the use of Bengali, the most widely spoken language in the state, as enemies of the state.

Language discrimination is suggested to be labeled linguicism or logocism. Anti-discriminatory and inclusive efforts to accommodate persons who speak different languages or cannot have fluency in the country's predominant or "official" language, is bilingualism such as official documents in two languages, and multiculturalism in more than two languages.

Name

Discrimination based on a person's name may also occur, with researchers suggesting that this form of discrimination is present based on a name's meaning, its pronunciation, its uniqueness, its gender affiliation, and its racial affiliation. Research has further shown that real world recruiters spend an average of just six seconds reviewing each résumé before making their initial "fit/no fit" screen-out decision and that a person's name is one of the six things they focus on most. France has made it illegal to view a person's name on a résumé when screening for the initial list of most qualified candidates. Great Britain, Germany, Sweden, and the Netherlands have also experimented with name-blind summary processes. Some apparent discrimination may be explained by other factors such as name frequency. The effects of name discrimination based on a name's fluency is subtle, small and subject to significantly changing norms.

Nationality

Discrimination on the basis of nationality is usually included in employment laws (see above section for employment discrimination specifically). It is sometimes referred to as bound together with racial discrimination although it can be separate. It may vary from laws that stop refusals of hiring based on nationality, asking questions regarding origin, to prohibitions of firing, forced retirement, compensation and pay, etc., based on nationality.

Discrimination on the basis of nationality may show as a "level of acceptance" in a sport or work team regarding new team members and employees who differ from the nationality of the majority of team members.

In the GCC states, in the workplace, preferential treatment is given to full citizens, even though many of them lack experience or motivation to do the job. State benefits are also generally available for citizens only. Westerners might also get paid more than other expatriates.

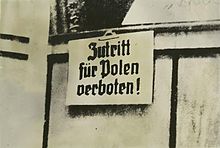

Race or ethnicity

Racial and ethnic discrimination differentiates individuals on the basis of real and perceived racial and ethnic differences and leads to various forms of the ethnic penalty. It can also refer to the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to physical appearance and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism directed against other people because they are of a different race or ethnicity. Modern variants of racism are often based in social perceptions of biological differences between peoples. These views can take the form of social actions, practices or beliefs, or political systems in which different races are ranked as inherently superior or inferior to each other, based on presumed shared inheritable traits, abilities, or qualities. It has been official government policy in several countries, such as South Africa during the apartheid era. Discriminatory policies towards ethnic minorities include the race-based discrimination against ethnic Indians and Chinese in Malaysia After the Vietnam War, many Vietnamese refugees moved to Australia and the United States, where they face discrimination.

Region

Regional or geographic discrimination is a form of discrimination that is based on the region in which a person lives or the region in which a person was born. It differs from national discrimination because it may not be based on national borders or the country in which the victim lives, instead, it is based on prejudices against a specific region of one or more countries. Examples include discrimination against Chinese people who were born in regions of the countryside that are far away from cities that are located within China, and discrimination against Americans who are from the southern or northern regions of the United States. It is often accompanied by discrimination that is based on accent, dialect, or cultural differences.

Religious beliefs

Religious discrimination is valuing or treating people or groups differently because of what they do or do not believe in or because of their feelings towards a given religion. For instance, the Jewish population of Germany, and indeed a large portion of Europe, was subjected to discrimination under Adolf Hitler and his Nazi party between 1933 and 1945. They were forced to live in ghettos, wear an identifying star of David on their clothes, and sent to concentration and death camps in rural Germany and Poland, where they were to be tortured and killed, all because of their Jewish religion. Many laws (most prominently the Nuremberg Laws of 1935) separated those of Jewish faith as supposedly inferior to the Christian population.

Restrictions on the types of occupations that Jewish people could hold were imposed by Christian authorities. Local rulers and church officials closed many professions to religious Jews, pushing them into marginal roles that were considered socially inferior, such as tax and rent collecting and moneylending, occupations that were only tolerated as a "necessary evil". The number of Jews who were permitted to reside in different places was limited; they were concentrated in ghettos and banned from owning land. In Saudi Arabia, non-Muslims are not allowed to publicly practice their religions and they cannot enter Mecca and Medina. Furthermore, private non-Muslim religious gatherings might be raided by the religious police.

In a 1979 consultation on the issue, the United States commission on civil rights defined religious discrimination in relation to the civil rights which are guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. Whereas religious civil liberties, such as the right to hold or not to hold a religious belief, are essential for Freedom of Religion (in the United States as secured by the First Amendment), religious discrimination occurs when someone is denied "equal protection under the law, equality of status under the law, equal treatment in the administration of justice, and equality of opportunity and access to employment, education, housing, public services and facilities, and public accommodation because of their exercise of their right to religious freedom".

Sex, sex characteristics, gender, and gender identity

Sexism is a form of discrimination based on a person's sex or gender. It has been linked to stereotypes and gender roles, and may include the belief that one sex or gender is intrinsically superior to another. Extreme sexism may foster sexual harassment, rape, and other forms of sexual violence. Gender discrimination may encompass sexism, and is discrimination toward people based on their gender identity or their gender or sex differences. Gender discrimination is especially defined in terms of workplace inequality. It may arise from social or cultural customs and norms.

Intersex persons experience discrimination due to innate, atypical sex characteristics. Multiple jurisdictions now protect individuals on grounds of intersex status or sex characteristics. South Africa was the first country to explicitly add intersex to legislation, as part of the attribute of 'sex'. Australia was the first country to add an independent attribute, of 'intersex status'. Malta was the first to adopt a broader framework of 'sex characteristics', through legislation that also ended modifications to the sex characteristics of minors undertaken for social and cultural reasons. Global efforts such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 5 is also aimed at ending all forms of discrimination on the basis of gender and sex.

Sexual orientation

One's sexual orientation is a "predilection for homosexuality, heterosexuality, or bisexuality". Like most minority groups, homosexuals and bisexuals are vulnerable to prejudice and discrimination from the majority group. They may experience hatred from others because of their sexuality; a term for such hatred based upon one's sexual orientation is often called homophobia. Many continue to hold negative feelings towards those with non-heterosexual orientations and will discriminate against people who have them or are thought to have them. People of other uncommon sexual orientations also experience discrimination. One study found its sample of heterosexuals to be more prejudiced against asexual people than to homosexual or bisexual people.

Employment discrimination based on sexual orientation varies by country. Revealing a lesbian sexual orientation (by means of mentioning an engagement in a rainbow organisation or by mentioning one's partner name) lowers employment opportunities in Cyprus and Greece but overall, it has no negative effect in Sweden and Belgium. In the latter country, even a positive effect of revealing a lesbian sexual orientation is found for women at their fertile ages.

Besides these academic studies, in 2009, ILGA published a report based on research carried out by Daniel Ottosson at Södertörn University College, Stockholm, Sweden. This research found that of the 80 countries around the world that continue to consider homosexuality illegal, five carry the death penalty for homosexual activity, and two do in some regions of the country. In the report, this is described as "State sponsored homophobia". This happens in Islamic states, or in two cases regions under Islamic authority. On February 5, 2005, the IRIN issued a reported titled "Iraq: Male homosexuality still a taboo". The article stated, among other things that honor killings by Iraqis against a gay family member are common and given some legal protection. In August 2009, Human Rights Watch published an extensive report detailing torture of men accused of being gay in Iraq, including the blocking of men's anuses with glue and then giving the men laxatives. Although gay marriage has been legal in South Africa since 2006, same-sex unions are often condemned as "un-African". Research conducted in 2009 shows 86% of black lesbians from the Western Cape live in fear of sexual assault.

A number of countries, especially those in the Western world, have passed measures to alleviate discrimination against sexual minorities, including laws against anti-gay hate crimes and workplace discrimination. Some have also legalized same-sex marriage or civil unions in order to grant same-sex couples the same protections and benefits as opposite-sex couples. In 2011, the United Nations passed its first resolution recognizing LGBT rights.

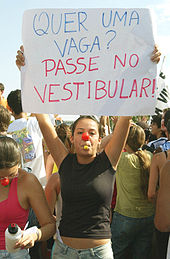

Reverse discrimination

Reverse discrimination is discrimination against members of a dominant or majority group, in favor of members of a minority or historically disadvantaged group. Groups may be defined in terms of disability, ethnicity, family status, gender identity, nationality, race, religion, sex, and sexual orientation, or other factors.

This discrimination may seek to redress social inequalities under which minority groups have had less access to privileges enjoyed by the majority group. In such cases it is intended to remove discrimination that minority groups may already face. Reverse discrimination can be defined as the unequal treatment of members of the majority groups resulting from preferential policies, as in college admissions or employment, intended to remedy earlier discrimination against minorities.

Conceptualizing affirmative action as reverse discrimination became popular in the early- to mid-1970s, a time period that focused on under-representation and action policies intended to remedy the effects of past discrimination in both government and the business world.

Anti-discrimination legislation

- Racial Discrimination Act 1975

- Sex Discrimination Act 1984

- Disability Discrimination Act 1992

- Age Discrimination Act 2004

- Sex Discrimination Ordinance (1996)

- Prohibition of Discrimination in Products, Services and Entry into Places of Entertainment and Public Places Law, 2000

- Employment (Equal Opportunities) Law, 1988

- Article 137c, part 1 of Wetboek van Strafrecht prohibits insults towards a group because of its race, religion, sexual orientation (straight or gay), handicap (somatically, mental or psychiatric) in public or by speech, by writing or by a picture. Maximum imprisonment one year of imprisonment or a fine of the third category.

- Part 2 increases the maximum imprisonment to two years and the maximum fine category to 4, when the crime is committed as a habit or is committed by two or more persons.

- Article 137d prohibits provoking to discrimination or hate against the group described above. Same penalties apply as in article 137c.

- Article 137e part 1 prohibits publishing a discriminatory statement, other than in formal message, or hands over an object (that contains discriminatory information) otherwise than on his request. Maximum imprisonment is 6 months or a fine of the third category.

- Part 2 increases the maximum imprisonment to one year and the maximum fine category to 4, when the crime is committed as a habit or committed by two or more persons.

- Article 137f prohibits supporting discriminatory activities by giving money or goods. Maximum imprisonment is 3 months or a fine of the second category.

United Kingdom

- Equal Pay Act 1970 – provides for equal pay for comparable work.

- Sex Discrimination Act 1975 – makes discrimination against women or men, including discrimination on the grounds of marital status, illegal in the workplace.

- Human Rights Act 1998 – provides more scope for redressing all forms of discriminatory imbalances.

United States

- Equal Pay Act of 1963 – (part of the Fair Labor Standards Act) – prohibits wage discrimination by employers and labor organizations based on sex.

- Civil Rights Act of 1964 – many provisions, including broadly prohibiting discrimination in the workplace including hiring, firing, workforce reduction, benefits, and sexually harassing conduct.

- Fair Housing Act of 1968 prohibited discrimination in the sale or rental of housing based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, familial status, or disability. The Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity is charged with administering and enforcing the Act.

- Pregnancy Discrimination Act, which amended Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 – covers discrimination based upon pregnancy in the workplace.

- Violence Against Women Act

- Racism still occurs in a widespread manner in real estate.

United Nations documents

Important UN documents addressing discrimination include:

- The Universal Declaration of Human Rights is a declaration adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on December 10, 1948. It states that:" Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status."

- The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) is a United Nations convention. The Convention commits its members to the elimination of racial discrimination. The convention was adopted and opened for signature by the United Nations General Assembly on December 21, 1965, and entered into force on January 4, 1969.

- The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) is an international treaty adopted in 1979 by the United Nations General Assembly. Described as an international bill of rights for women, it came into force on September 3, 1981.

- The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities is an international human rights instrument treaty of the United Nations. Parties to the convention are required to promote, protect, and ensure the full enjoyment of human rights by persons with disabilities and ensure that they enjoy full equality under the law. The text was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on December 13, 2006, and opened for signature on March 30, 2007. Following ratification by the 20th party, it came into force on May 3, 2008.

Theories and philosophy

Social theories such as egalitarianism assert that social equality should prevail. In some societies, including most developed countries, each individual's civil rights include the right to be free from government sponsored social discrimination. Due to a belief in the capacity to perceive pain or suffering shared by all animals, "abolitionist" or "vegan" egalitarianism maintains that the interests of every individual (regardless its species), warrant equal consideration with the interests of humans, and that not doing so is "speciesist".

Philosophers have debated as to how inclusive the definition of discrimination should be. Some philosophers have argued that discrimination should only refer to wrongful or disadvantageous treatment in the context of a socially salient group (such as race, gender, sexuality etc.) within a given context. Under this view, failure to limit the concept of discrimination would lead to it being overinclusive; for example, since most murders occur because of some perceived difference between the perpetrator and the victim, many murders would constitute discrimination if the social salience requirement is not included. Thus this view argues that making the definition of discrimination overinclusive renders it meaningless. Conversely, other philosophers argue that discrimination should simply refer to wrongful disadvantageous treatment regardless of the social salience of the group, arguing that limiting the concept only to socially salient groups is arbitrary, as well as raising issues of determining which groups would count as socially salient. The issue of which groups should count has caused many political and social debates.

Based on realistic-conflict theory and social-identity theory, Rubin and Hewstone have highlighted a distinction among three types of discrimination:

- Realistic competition is driven by self-interest and is aimed at obtaining material resources (e.g., food, territory, customers) for the in-group (e.g., favoring an in-group in order to obtain more resources for its members, including the self).

- Social competition is driven by the need for self-esteem and is aimed at achieving a positive social status for the in-group relative to comparable out-groups (e.g., favoring an in-group in order to make it better than an out-group).

- Consensual discrimination is driven by the need for accuracy and reflects stable and legitimate intergroup status hierarchies (e.g., favoring a high-status in-group because it is high status).

Labeling theory

Discrimination, in labeling theory, takes form as mental categorization of minorities and the use of stereotype. This theory describes difference as deviance from the norm, which results in internal devaluation and social stigma that may be seen as discrimination. It is started by describing a "natural" social order. It is distinguished between the fundamental principle of fascism and social democracy. The Nazis in 1930s-era Germany and the pre-1990 Apartheid government of South Africa used racially discriminatory agendas for their political ends. This practice continues with some present day governments.

Game theory

Economist Yanis Varoufakis (2013) argues that "discrimination based on utterly arbitrary characteristics evolves quickly and systematically in the experimental laboratory", and that neither classical game theory nor neoclassical economics can explain this. Varoufakis and Shaun Hargreaves-Heap (2002) ran an experiment where volunteers played a computer-mediated, multiround hawk-dove game. At the start of each session, each participant was assigned a color at random, either red or blue. At each round, each player learned the color assigned to his or her opponent, but nothing else about the opponent. Hargreaves-Heap and Varoufakis found that the players' behavior within a session frequently developed a discriminatory convention, giving a Nash equilibrium where players of one color (the "advantaged" color) consistently played the aggressive "hawk" strategy against players of the other, "disadvantaged" color, who played the acquiescent "dove" strategy against the advantaged color. Players of both colors used a mixed strategy when playing against players assigned the same color as their own.

The experimenters then added a cooperation option to the game, and found that disadvantaged players usually cooperated with each other, while advantaged players usually did not. They state that while the equilibria reached in the original hawk-dove game are predicted by evolutionary game theory, game theory does not explain the emergence of cooperation in the disadvantaged group. Citing earlier psychological work of Matthew Rabin, they hypothesize that a norm of differing entitlements emerges across the two groups, and that this norm could define a "fairness" equilibrium within the disadvantaged group.