From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Biblical criticism is an umbrella term for those methods of studying the Bible that embrace two distinctive perspectives: the concern to avoid

dogma and

bias by applying a

non-sectarian,

reason-based judgment, and the reconstruction of history according to

contemporary understanding. Biblical criticism uses the grammar,

structure, development, and relationship of language to identify such

characteristics as the Bible's literary structure, its

genre, its context, meaning, authorship, and origins.

Biblical criticism includes a wide range of approaches and questions within four major contemporary methodologies:

textual,

source,

form, and

literary

criticism. Textual criticism examines the text and its manuscripts to

identify what the original text would have said. Source criticism

searches the texts for evidence of original sources. Form criticism

identifies short units of text and seeks to identify their original

setting. Each of these is primarily historical and pre-compositional in

its concerns. Literary criticism, on the other hand, focuses on the

literary structure, authorial purpose, and reader's response to the text

through methods such as

rhetorical criticism,

canonical criticism, and

narrative criticism.

Biblical criticism began as an aspect of the rise of

modern culture in the West. Some scholars claim that its roots reach back to the

Reformation, but most agree it grew out of the

German Enlightenment. German

pietism played a role in its development, as did British

deism, with its greatest influences being

rationalism and

Protestant

scholarship. The Enlightenment age and its skepticism of biblical and

ecclesiastical authority ignited questions concerning the historical

basis for the man

Jesus separately from traditional theological views concerning him. This "

quest" for the

Jesus of history

began in biblical criticism's earliest stages, reappeared in the

nineteenth century, and again in the twentieth, remaining a major

occupation of biblical criticism, on and off, for over 200 years.

In the late twentieth and early twenty-first century, biblical criticism was influenced by a wide range of additional

academic disciplines and

theoretical perspectives, changing it from a primarily historical approach to a

multidisciplinary field. In a field long dominated by white male

Protestants, non-white scholars, women, and those from the Jewish and Catholic traditions became prominent voices.

Globalization brought a broader spectrum of worldviews into the field, and other academic disciplines as diverse as

Near Eastern studies,

psychology,

anthropology and

sociology formed new methods of biblical criticism such as socio-scientific criticism and psychological biblical criticism. Meanwhile,

post-modernism and post-critical interpretation began questioning biblical criticism's role and function.

History

Beginnings: the eighteenth century

Title page of Richard Simon's Critical History (1685), an early work of biblical criticism

According to tradition,

Moses was the author of the first five books of the Bible, including the

book of Genesis. Philosophers and theologians such as

Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679),

Benedict Spinoza (1632–1677), and

Richard Simon

(1638–1712) questioned Mosaic authorship. Spinoza said Moses could not

have written the preface to Deuteronomy, since he never crossed the

Jordan; he points out that Deuteronomy 31:9 references Moses in the

third person; and he lists multiple other inconsistencies and anomalies

that led him to conclude "it was plain" these Pentateuchal books were

not written by Moses himself.

Jean Astruc (1684–1766), a French physician, believed these critics were wrong about

Mosaic authorship. According to Old Testament scholar

Edward Young, Astruc believed Moses used hereditary accounts of the Hebrew people to assemble the book of Genesis. So, Astruc borrowed methods of

textual criticism,

used to investigate Greek and Roman texts, and applied them to the

Bible in search of those original accounts. Astruc believed he

identified them as separate sources that were edited together into the

book of Genesis, thus explaining Genesis' problems while still allowing

for Mosaic authorship.

Astruc's method was adopted and developed at the twenty or so

Protestant universities in Germany. There was a willingness among the

doctoral candidates to re-express Christian doctrine in terms of the

scientific method and the historical understanding common during the

German Enlightenment (circa 1750–1850).

German

pietism played a role in the rise of biblical criticism by supporting the desire to break the hold of religious authority.

Rationalism

was also a significant influence in biblical criticism's development,

providing its concern to avoid dogma and bias through reason.

For example, the Swiss theologian

Jean Alphonse Turretin (1671–1737) attacked conventional

exegesis

(interpretation) and argued for critical analysis led solely by reason.

Turretin believed the Bible could be considered authoritative even if

it was not considered

inerrant. This has become a common modern Judeo-Christian view.

Johann Salomo Semler

(1725–1791) argued for an end to all doctrinal assumptions, giving

historical criticism its non-sectarian nature. As a result, Semler is

often called the father of

historical-critical research.

Semler distinguished between "inward" and "outward" religion, the idea

that, for some people, their religion is their highest inner purpose,

while for others, religion is a more exterior practice: a tool to

accomplish other purposes more important to the individual such as

political or economic goals. This is a

concept recognized by modern psychology.

Communications scholar

James A. Herrick

says even though most scholars agree that biblical criticism evolved

out of the German Enlightenment, there are also histories of biblical

scholarship that have found "strong direct links" with British

deism. Herrick references the theologian

Henning Graf Reventlow as saying deism included the

humanist world view, which has also been significant in biblical criticism. Some scholars, such as

Gerhard Ebeling (1912–2001),

Rudolf Bultmann (1884–1976), and

Ernst Käsemann (1906–1998) trace biblical criticism's origins to the

Reformation.

Three early scholars of the Reformation era who helped lay the foundations of modern biblical criticism were

Joachim Camerarius (1500–1574),

Hugo Grotius (1583–1645), and

Matthew Tindal

(1653–1733). Camerarius advocated for using context to interpret Bible

texts. Grotius paved the way for comparative religion studies by

analyzing New Testament texts in light of Classical, Jewish and early

Christian writings. Tindal, as part of English deism, asserted that

Jesus taught

natural religion,

an undogmatic faith that was later changed by the Church. This view

drove a wedge between scripture and the Church's claims of religious

truth.

The first scholar to separate the

historical Jesus from the theological Jesus was philosopher, writer, classicist, Hebraist and Enlightenment free thinker

Hermann Samuel Reimarus (1694–1768). Copies of Reimarus' writings were discovered by

G. E. Lessing

(1729–1781) in the library at Wolfenbüttel where he was librarian.

Reimarus had left permission for his work to be published after his

death, and Lessing did so between 1774 and 1778, publishing them as

Die Fragmente eines unbekannten Autors (

The Fragments of an Unknown Author). Over time, they came to be known as the

Wolfenbüttel Fragments

after the library where Lessing worked. Reimarus distinguished between

what Jesus taught and how he is portrayed in the New Testament.

According to Reimarus, Jesus was a political

Messiah

who failed at creating political change and was executed. His disciples

then stole the body and invented the story of the resurrection for

personal gain.

Reimarus' controversial work prompted a response from Semler in 1779,

Beantwortung der Fragmente eines Ungenannten (

Answering the Fragments of an Unknown).

Semler refuted Reimarus' arguments, but it was of little consequence. Reimarus' writings had already made a lasting change in the practice of

biblical criticism by making it clear such criticism could exist

independently of theology and faith. Reimarus had shown biblical

criticism could serve its own ends, be governed solely by rational

criteria, and reject deference to religious tradition.

Lessing contributed to the field of biblical criticism by seeing

Reimarus' writings published, but he also made contributions of his own

work, arguing that the proper study of biblical texts requires knowing

the context in which they were written. This has since become an

accepted concept. During this period, the biblical scholar

Johann David Michaelis

(1717–1791) wrote the first historical-critical introduction to the New

Testament, in which the historical study of each book of the Bible is

discussed. Instead of interpreting the Bible historically,

Johann Gottfried Eichhorn (1752–1827),

Johann Philipp Gabler (1753–1826), and

Georg Lorenz Bauer

(1755–1806) took a different approach. They used the concept of myth as

a tool for interpreting the Bible. This concept was later picked up by

Rudolf Bultmann and it became particularly influential in the early twentieth century.

The nineteenth century

Theologians

Richard and Kendall Soulen say biblical criticism reached full flower

in the nineteenth century, becoming the "major transforming fact of

biblical studies in the modern period" and noted that the people working

at that time "saw themselves as continuing the aims of the Protestant

Reformation."

Landmarks in understanding the Bible and its background were achieved

during this century, with many modern concepts having their roots here.

For example, in 1835 and again in 1845, theologian

Ferdinand Christian Baur (1792–1860) postulated a sharp contrast between the

apostles Peter and

Paul.

Since then, this concept has had widespread debate within topics such

as Pauline and New Testament studies, early church studies, Jewish Law,

the theology of grace, and the doctrine of justification.

Foundations of anti-Jewish bias were also established in the field at this time under the guise of scholarly objectivity.

The first Enlightenment Protestant to call for the "de-Judaizing" of

Christianity was Johann Semler. The "emancipation of reason" from the

Word of God

was a primary goal of Semler and the Enlightenment exegetes, yet the

picture of the Jews and Judaism found in biblical criticism of this

period is colored by classic anti-Jewish stereotypes "despite the

tradition's lip-service to emancipation."

He took a stand against discrimination in society while at the same

time writing theology that was strongly negative toward the Jews and

Judaism. He saw Christianity as something new and universal that

supersedes all that came before it.

This stark contrast between Judaism and Christianity became a common

theme, along with a strong prejudice against Jews and Judaism, in

Herder,

Schleiermacher,

de Wette,

Baur,

Strauss,

Ritschl, the

history of religions school, and on into the form critics of the Twentieth century until World War II.

Biblical criticism was divided into

higher criticism and

lower criticism

during this century. Higher criticism focuses on the Bible's

composition and history, while lower criticism is concerned with

interpreting its meaning for its readers. Later in the 19th century, the discovery of

ancient manuscripts revolutionized textual criticism and translation. During this period, Bible scholar

H. J. Holtzmann developed a listing of the chronological order of the New Testament.

The height of biblical criticism is also represented by the history of religions school (known in German as the

Kultgeschichtliche Schule or alternatively the

Religionsgeschichtliche Schule).

This school was a group of German Protestant theologians associated with the

University of Göttingen

in the late 19th century who sought to understand Judaism and

Christianity within their relationship to other religions of the Near

East.

The late nineteenth century saw the second "

quest for the historical Jesus" which primarily involved writing versions of the "life of Jesus." Important scholars of this quest included

David Strauss

(1808–1874), whose cultural significance is in his contribution to

weakening the established authorities, and whose theological

significance is in his confrontation of the doctrine of Christ's

divinity with the modern critical study of history.

Adolf Von Harnack (1851–1930) contributed to the quest for the historical Jesus, writing

The Essence of Christianity in 1900, where he described Jesus as a reformer.

William Wrede (1859–1906) was a forerunner of redaction criticism.

Ernst Renan (1823–1892) promoted the critical method and was opposed to orthodoxy.

Johannes Weiss (1863–1914),

W. Bousset,

Hermann Gunkel, and

William Wrede were key figures in the founding of the

Religionsgeschichtliche Schule in Göttingen in the 1890s.

While at Göttingen, Weiss wrote his most influential work on the apocalyptic proclamations of Jesus. It was left to

Albert Schweitzer

(1875–1965) to finish pursuit of the apocalyptic Jesus and

revolutionize New Testament scholarship at the turn of the century. He

proved to most of that scholarly world that Jesus' teachings and actions

were determined by his

eschatological

outlook. He also critiqued the romanticized "lives of Jesus" as built

on dubious assumptions reflecting more of the life of the author than

Jesus.

The twentieth century

In the early part of the twentieth century,

Karl Barth,

Rudolf Bultmann, and others moved away from concern over the historical Jesus and concentrated instead on the

kerygma: the message of scholars such as theologian Konrad Hammann call Bultmann the "giant of

twentieth-century New Testament biblical criticism: His pioneering

studies in biblical criticism shaped research on the composition of the

gospels, and his call for

demythologizing biblical language sparked debate among Christian theologians worldwide."

Bultmann's demythologizing refers to the reinterpretation of the

biblical myths (myth is defined as descriptions of the divine in human

terms). It is not the elimination of myth but is, instead, its

re-expression in terms of the

existential philosophy of

Martin Heidegger. Bultmann claimed myths are "true" anthropologically and existentially but not cosmologically. As a major proponent of

form criticism, Bultmann's views "set the agenda for a generation of leading New Testament scholars".

Redaction criticism

was also a common form of biblical criticism used in the early to

mid-twentieth century. While form criticism divided the text into small

units, redaction emphasized the literary integrity of the larger

literary units.

The discovery of the

Dead Sea scrolls at

Qumran

in 1948 renewed interest in the contributions archaeology could make to

biblical studies as well as to the challenges it presented to various

aspects of biblical criticism.

New Testament scholar

Joachim Jeremias used linguistics and history to describe Jesus' Jewish environment.

The biblical theology movement of the 1950s produced a massive debate

between Old Testament and New Testament scholars over the unity of the

Bible. The rise of redaction criticism closed it by bringing about a

greater emphasis on diversity.

After 1970, biblical criticism began to change radically and pervasively.

New criticism (literary criticism) developed.

New historicism, a

literary theory that views history through literature, also developed. Biblical criticism began to apply new literary approaches such as

structuralism and

rhetorical criticism, which were less concerned with history and more concerned with the texts themselves.

In the 1970s, the New Testament scholar

E. P. Sanders advanced the

New Perspective on Paul, which has greatly influenced scholarly views on the relationship between

Pauline Christianity and

Jewish Christianity in the

Pauline epistles.

Sanders also advanced study of the historical Jesus by putting Jesus' life in the context of first-century

Second Temple Judaism. In 1974, the theologian

Hans Frei published

The Eclipse of Biblical Narrative, which became a landmark work leading to the development of

post-critical biblical interpretation. The third period of focused study on the historical Jesus began in 1985 with the

Jesus Seminar.

By 1990, biblical criticism was no longer primarily a historical

discipline but was instead a group of disciplines with often conflicting

interests.

New perspectives from different ethnicities, feminist theology,

Catholicism and Judaism revealed an "untapped world" previously

overlooked by the majority of white male Protestants who had dominated

biblical criticism from its beginnings.

Globalization brought different world views, while other academic

fields such as Near Eastern studies, sociology, and anthropology became

active in biblical criticism as well. These new points of view created

awareness that the Bible can be rationally interpreted from many

different perspectives.

In turn, this awareness changed biblical criticism's central concept

from the criteria of neutral judgment to that of beginning from a

recognition of the various biases the reader brings to the study of the

texts.

Major methods of criticism

Theologian

David R. Law writes that textual, source, form, and redaction criticism

are employed together by biblical scholars. The Old Testament (the

Hebrew Bible) and the New Testament are distinct bodies of literature

that raise their own problems of interpretation. Therefore, separating

these methods, and addressing the Bible as a whole, is an artificial

approach that is necessary only for the purpose of description.

Textual criticism

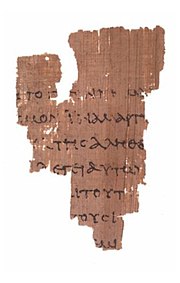

Textual criticism examines the text itself and all associated manuscripts to determine the original text.

It is one of the largest areas of Biblical criticism in terms of the

sheer amount of information it addresses. The roughly 900 manuscripts

found at Qumran include the oldest extant manuscripts of the Hebrew

Bible. They represent every book except Esther, though most are

fragmentary. The

New Testament has been preserved in more

manuscripts than any other ancient work, having over 5,800 complete or fragmented

Greek manuscripts, 10,000

Latin manuscripts and 9,300 manuscripts in various other ancient languages including

Syriac,

Slavic,

Gothic,

Ethiopic,

Coptic and

Armenian. The dates of these manuscripts range from c.110—125 (the

papyrus) to the introduction of printing in Germany in the 15th

century. There are also a million New Testament quotations in the

collected writings of the

Church Fathers of the first four centuries. As a comparison, the next best-sourced ancient text is Homer's

Iliad,

which is found in more than 1,900 manuscripts, though many are of a

fragmentary nature. The two chief works of the first-century Roman

historian

Tacitus,

Annales and

Historiae, each survive in only a single medieval manuscript. There are a total of 476 extant non-Christian manuscripts dated to the second century.

These texts were all written by hand, by copying from another

handwritten text, so they are not alike in the manner of a printed work.

The differences between them are called variants.

A variant is simply any variation between two texts, and while the

exact number is somewhat disputed, scholars agree the more texts, the

more variants. This means there are more variants concerning New

Testament texts than Old Testament texts.

Variants are not evenly distributed throughout the texts. Textual scholar

Kurt Aland explains that charting the variants shows the New Testament is 62.9% variant-free.

Many variants originate in simple misspellings or mis-copying. For

example, a scribe would drop one or more letters, skip a word or line,

write one letter for another, transpose letters, and so on. Some

variants represent a scribal attempt to simplify or harmonize, by

changing a word or a phrase. Ehrman explains: scribe

'A' will introduce mistakes which are not in the manuscript of scribe

'B'. Copies of text

'A'

with the mistake will subsequently contain that same mistake. The

multiple generations of texts that follow, containing the error, are

referred to as a "family" of texts. Over time the texts descended from

'A' that share the error, and those from

'B'

that do not share it, will diverge further, but later texts will still

be identifiable as descended from one or the other because of the

presence or absence of that original mistake. Textual criticism studies

the differences between these families to piece together what the

original looked like.

Sorting out the wealth of source material is complex, so textual

families were sorted into categories tied to geographical areas. The

divisions of the New Testament textual families were

Alexandrian (also called the "Neutral text"),

Western (Latin translations), and

Eastern (used by

Antioch and

Constantinople).

Forerunners of modern textual criticism can be found in both early

Rabbinic Judaism and the early church.

Rabbis addressed variants in the Hebrew texts as early as AD 100.

Tradition played a central role in their task of producing a standard

version of the Hebrew Bible. The Hebrew text they produced stabilized by

the end of the second century, and has come to be known as the

Masoretic text, the source of the Christian Old Testament.

However, the discovery of the

Dead Sea Scrolls

in 1947 has created problems. While 60% of the Dead Sea manuscripts are

closely related to Masoretic tradition, others bear a closer

resemblance to the

Septuagint (the ancient Greek version of the Hebrew texts) and the

Samaritan Pentateuch.

For textual criticism, this has raised the question of whether or not

there is such a thing that can be considered "original text."

The two main processes of textual criticism are

recension

and emendation. Recension is the selection of the most trustworthy

evidence on which to base a text. Emendation is the attempt to eliminate

the errors which are found even in the best manuscripts.

Despite its use of objective rules, there is a subjective element

involved in textual criticism. The textual critic chooses a reading

based on personal judgment, experience and common-sense. Biblical

scholar

David Clines gives the example of

Amos

6.12. It reads: "Does one plough with oxen? The obvious answer is

'yes', but the context of the passage seems to demand a 'no'; the usual

reading therefore is to amend this to, 'Does one plough

the sea

with oxen?' The amendment has a basis in the text, which is believed to

be corrupted, but is nevertheless a matter of personal judgment."

All of this contributes to textual criticism being one of the

most contentious areas of biblical criticism as well as the largest. It uses specialized methodologies, enough specialized terms to create its own lexicon,

and is guided by a number of principles. Yet any of these can be

contested, as well as any conclusions based on them, and they often are.

For example, in the late 1700s, textual critic

Johann Jacob Griesbach developed fifteen critical principles for determining which texts are likely the oldest and closest to the original. One of Griesbach's rules is

lectio brevior praeferenda:

"the shorter reading is preferred". This was based on the idea scribes

were more likely to add to a text than omit from it, making shorter

texts more likely to be older. Latin scholar Albert C. Clark challenged

this in 1914.

Based on his study of

Cicero,

Clark argued omission was a more common scribal error than addition,

saying "A text is like a traveler who goes from one inn to another

losing an article of luggage at each stop."

Clark's claims were criticized by those who supported Griesbach's

principles. Clark responded, but disagreement continued. Nearly eighty

years later, the theologian and priest James Royse took up the case.

After close study of multiple New Testament papyri, he concluded Clark

was right. Some scholars have recently called to abandon older approaches to

textual criticism in favor of new computer-assisted methods for

determining manuscript relationships in a more reliable way.

Source criticism

Source criticism

is the search for the original sources that form the basis of biblical

text. It can be traced back to the 17th-century French priest

Richard Simon.

In Old Testament studies, source criticism is generally focused on

identifying sources within a single text. For example, the modern view

of the origins of the book of Genesis was first laid in 1753 by the

French physician

Jean Astruc. He presumed

Moses

used ancient documents to write it, so his goal was identifying and

reconstructing those documents by separating the book of Genesis back

into those original sources. He discovered Genesis alternates use of two

different names for God while the rest of the Pentateuch after

Exodus 3 omits that alternation.

He found repetitions of certain events, such as parts of the

flood story

that are repeated three times. He also found apparent anachronisms:

statements seemingly from a later time than Genesis was set. Astruc

hypothesized that this separate material was fused into a single unit

that became the book of Genesis thereby creating its duplications and

parallelisms.

Further examples of the products of source criticism include its two

most influential and well-known theories concerning the origins of the

Pentateuch (the

Documentary hypothesis) and the four gospels (

two-source hypothesis).

Wellhausen's documentary hypothesis

Theologian

Antony F. Campbell says source criticism's most influential work is

Julius Wellhausen's

Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels (

Prologue to the History of Israel, 1878) which sought to establish the sources of the first five books of the Old Testament.

Wellhausen correlated the history and development of those five books,

known as the Pentateuch, with the development of the Jewish faith.

The Documentary hypothesis, also known as the

JEDP theory, or the Wellhausen theory, says the Pentateuch was combined out of four separate and coherent sources known as

J (which stands for

Yahwist, which is spelled with a

J in German),

E (for

Elohist),

D (for

Deuteronomist), and

P (for the

Priestly source). Old Testament scholar

Karl Graf (1815–1869) suggested the

P in 1866 as the last stratum of the Wellhausen theory.

Therefore, the Documentary hypothesis is sometimes also referred to as the

Graf–Wellhausen hypothesis.

Later scholars inferred more sources, with increasing information about their extent and inter-relationship.

The fragmentary theory was a later understanding of Wellhausen

produced by form criticism. This theory argues that fragments of various

documents, and not continuous documents, are the sources for the

Pentateuch. This accounts for diversity but not structural and

chronological consistency. The

Supplementary hypothesis

can be seen as an evolution of the Documentary hypothesis that

solidified in the 1970s. Proponents of this view assert three sources

for the Pentateuch, with the Deuteronomist as the oldest source, and the

Torah assembled from a central core document, the Elohist, then

supplemented by fragments taken from other sources.

Advocates of the Documentary hypothesis contend it accounts well

for the differences and duplication found in each of the Pentateuchal

books. Furthermore, they argue, it provides an explanation for the

peculiar character of the material labeled P, which reflects the

perspective and concerns of Israel's priests. However, the original

theory has also been heavily criticized. Old Testament scholar

Ernest Nicholson

says that by the end of the 1970s and into the 1990s, "one major study

after another, like a series of hammer blows, ... rejected the main

claims of the Documentary theory, and the criteria on ... which those

claims are grounded."

It has been criticized for its dating of the sources, for assuming that

the original sources were coherent, and for assuming E and P were

originally complete documents. Studies of the literary structure of the

Pentateuch have shown J and P used the same structure, and that motifs

and themes cross the boundaries of the various sources, which undermines

arguments for separate origins.

Problems and criticisms of the Documentary hypothesis have been brought

on by such literary analysis, but also by anthropological developments,

and by various archaeological findings, such as those indicating Hebrew

is older than previously believed.

Presently, few biblical scholars still hold to Wellhausen's Documentary

hypothesis in its classical form. However, while current debate has

modified Wellhausen's conclusions, Nicholson says "for all that it needs

revision and development in detail, [the work of Wellhausen] remains

the securest basis for understanding the Pentateuch." Critical scholar Pauline Viviano agrees, stating that the general contours of Wellhausen's view remain with the

Newer Documentary Hypothesis providing the best answers to the complex question of how the Pentateuch was formed.

The New Testament synoptic problem

The widely-accepted two-source hypothesis, showing two sources for both Matthew and Luke

Streeter's

four source hypothesis, showing four sources each for Matthew and Luke

with the colors representing the different sources

In New Testament studies, source criticism has taken a slightly

different approach from Old Testament studies by focusing on identifying

the common sources of multiple texts. This has revealed the Gospels are

both products of sources and sources themselves.

As sources,

Matthew,

Mark and

Luke are partially dependent on each other and partially independent of each other. This is called the

synoptic problem, and explaining it is the single greatest dilemma of New Testament source criticism.

Multiple theories exist to address the dilemma. However, two theories have become predominant: the

two-source hypothesis and the

four-source hypothesis.

Mark is the shortest of the four gospels with only 661 verses,

but six hundred of those verses are in Matthew and 350 of them are in

Luke. Some of these verses are copied verbatim. Most scholars agree that

this indicates Mark was a source for Matthew and Luke. There is also

some verbatim agreement between Matthew and Luke of verses not found in

Mark. In 1838, the religious philosopher

Christian Hermann Weisse

developed a theory about this. He postulated a hypothetical collection

of Jesus' sayings from an additional source called Q, taken from

Quelle, which is German for "source". If this document existed, it has now been lost, but some of its

material can be deduced indirectly. Comparing what is common to Matthew

and Luke, yet absent in Mark, the critical scholar

Heinrich Julius Holtzmann

demonstrated (in 1863) the probable existence of Q well enough for it

to be accepted as a likely second source, along with Mark, for Matthew

and Luke. This allowed the two-source hypothesis to emerge as the best

supported of the various synoptic solutions.

There is also material unique to each gospel. This indicates additional

separate sources for Matthew and for Luke. Biblical scholar

B. H. Streeter used this insight to refine and expand the two-source theory into a four-source theory in 1925.

While most scholars agree that the two-source theory offers the

best explanation for the Synoptic problem, it has not gone without

dispute. The Synoptic Seminar disbanded in 1982, reporting that its

members "could not agree on a single thing", leading some to claim the

problem is unsolvable.No single theory offers a complete solution. There are complex and

important difficulties that create challenges to every theory. One example is

Basil Christopher Butler's challenge to the legitimacy of two-source theory, arguing it contains a

Lachmann fallacy that says the two-source theory loses cohesion when it is acknowledged that no source can be established for Mark.

Form criticism

Form criticism began in the early twentieth century when theologian

Karl Ludwig Schmidt

observed that Mark's Gospel is composed of short units. Schmidt

asserted these small units were remnants and evidence of the oral

tradition that preceded the writing of the gospels.

Bible scholar

Richard Bauckham says this "most significant insight," which established the foundation of form criticism, has never been refuted.

Hermann Gunkel (1862–1932) and

Martin Dibelius (1883-1947) built from this insight and pioneered form criticism. Form criticism breaks the Bible down into those short units, called

pericopes,

which are then classified by genre: prose or verse, letters, laws,

court archives, war hymns, poems of lament, and so on. Form criticism

then theorizes concerning the individual pericope's

Sitz im Leben ("setting in life" or "place in life"). Based on their understanding of

folklore,

form critics believed the early Christian communities formed the

sayings and teachings of Jesus according to their needs (their

"situation in life"), and that each form could be identified by the

situation in which it had been created.

Form criticism, represented by Rudof Bultmann, its most influential

proponent, was the dominant method in the field of biblical criticism

for nearly 80 years. However, Old Testament scholar

Rolf Knierim

says contemporary scholars have produced an "explosion of studies" on

structure, genre, text-type, setting and language that challenge several

of its aspects and assumptions.

Biblical scholar

Richard Burridge explains:

The general critique of form criticism came from various

sources, putting several areas in particular under scrutiny. The analogy

between the development of the gospel pericopae and folklore needed

reconsideration because of developments in folklore studies; it was less

easy to assume the steady growth of an oral tradition in stages... the

length of time needed for the "laws" of oral transmission to operate was

greater than taken by the gospels; even the existence of such laws was

questioned.

In the early to mid twentieth century, Bultmann and other form

critics said they had found oral "laws of development" within the New

Testament.

In the 1970s, New Testament scholar

E. P. Sanders argued against the existence of such laws.

During the latter half of the twentieth century, observations from

field studies of cultures with existing oral traditions lent support to

Sanders' view.

For example, in 1978 linguists

Milman Parry and

Albert Bates Lord observed that oral tradition does not develop in the same manner as written texts.

Writing tends to develop in a linear manner, beginning with a crude

first draft which is then edited bit by bit to become more polished.

Oral tradition is more complex and multidirectional in its development.

Religion scholar Burke O. Long sums up the contemporary view by

observing that, since oral tradition does not follow the same

developmental pattern as written texts, laws of oral development cannot

be arrived at by studying written texts.

Additional challenges of form criticism have also been raised.

For example, biblical studies scholar Werner H. Kelber says form

criticism throughout the mid-twentieth century was so focused toward

finding each pericope's original form, that it distracted from any

serious consideration of memory as a dynamic force in the construction

of the gospels or the early church community tradition.

What Kelber refers to as form criticism's "astounding myopia" has

produced enough criticism to revive interest in memory as an analytical

category within biblical criticism.

Knierim says

Sitz im Leben has been challenged by studies that demonstrate a text type "does not automatically reveal the setting." Another example concerns the

Hellenistic culture that surrounded

first-century Palestine. Form criticism assumed the early Church was heavily influenced by that culture.

However, in the 1970s, E. P. Sanders, as well as Gerd Theissen, sparked

new rounds of studies that included anthropological and sociological

perspectives, reestablishing Judaism as the predominant influence on

Jesus, Paul and the New Testament. New Testament scholar

N. T. Wright says, "The earliest traditions of Jesus reflected in the Gospels are written from the perspective of

Second Temple Judaism [and] must be interpreted from the standpoint of

Jewish eschatology and

apocalypticism."

Bultmann has been personally criticized for being overly focused on

Heidegger's philosophy in his philosophical foundation, and for working with

a priori

notions concerning "folklore, the distinction between Palestinian and

Hellenistic communities, the length of the oral period, and more, that

were not derived from study but were instead constructed according to a

preconceived pattern".

For some, the many challenges to form criticism mean its future is in doubt. Bible scholar Anthony J. Campbell says:

Form criticism had a meteoric rise in the early part of

the twentieth century and fell from favor toward its end. For some, the

future of form criticism is not an issue: it has none. But if form

criticism embodies an essential insight, it will continue. ...Two

elements embody this insight and give it its value: concern for the

nature of the text and for its shape and structure... If the

encrustations can be scraped away, the "good stuff" may still be there.

Redaction criticism

A diagram of the complexity of the Synoptic problem

Redaction is the process of editing multiple sources, often

with a similar theme, into a single document. Redaction critics focus on

discovering how the literary units were originally

edited—"redacted"—into their current forms.

Redaction criticism

developed after World War II in Germany and in the 1950s in England and

North America, and can be seen as a correlative to form criticism.

It is dependent on both source and form criticism, because it is

necessary to identify the traditions before determining how the redactor

has made use of them.

However, redaction criticism rejects source and form criticism's

description of the Bible texts as mere collections of fragments. Where

form criticism fractures the biblical elements into smaller and smaller

individual pieces, redaction criticism attempts to interpret the whole

literary unit. As a result, redaction criticism "provides a corrective to the methodological imbalance of form criticism".

Form criticism saw the synoptic writers as mere collectors and focused on the

Sitz im Leben

as the creator of the texts. Redaction criticism deals more positively

with the Gospel writers restoring an understanding of them as

theologians of the early church.

Bible scholars Richard and Kendall Soulen explain that when redaction

criticism is applied to the synoptic gospels, "it is the evangelist's

use, disuse or alteration of the traditions open to him that is in view,

rather than the form and original setting of the traditions

themselves."

Since redaction criticism was developed from form criticism, it

shares many of its weaknesses. For example, it assumes an extreme

skepticism toward the historicity of Jesus and the gospels just as form

criticism does. Redaction criticism seeks the historical community of

the final redactors of the gospels, though there is often no textual

clue, and its method in finding the final editor's theology is flawed.

In the New Testament, redaction discerns the evangelist's theology by

focusing and relying upon the differences between the gospels, yet it is

unclear whether every difference has theological meaning, how much

meaning, or whether a difference is a stylistic or even an accidental

change. Further, it is not at all clear whether the difference was made

by the evangelist, who could have used the already–changed–story when

writing a gospel.

The evangelist's theology more likely depends on what the gospels have in common as well as their differences.

One of the weaknesses of redaction criticism in its New Testament

application is that it assumes Markan priority. Redaction criticism can

only function when sources are already known, and since redaction

criticism of the Synoptics has been based on the Markan priority of

two-source theory, if the priority of Matthew is ever established,

redaction criticism would have to begin all over again.

Followers of other theories concerning the Synoptic problem, such as those who support the

Greisbach hypothesis which says Matthew was written first, Luke second, and Mark third, do not accept redaction criticism.

Literary criticism

Statue of Northrop Frye, an important figure in biblical criticism, on a bench in Toronto.

Literary criticism shifted scholarly attention from historical and

pre-compositional matters to the text itself, becoming the dominant form

of biblical criticism in a relatively short period of about thirty

years. New Testament scholar

Paul R. House

says the discipline of linguistics, new views of historiography, and

the decline of older methods of criticism opened the door for literary

criticism. In 1957 literary critic

Northrop Frye

wrote an analysis of the Bible from the perspective of his literary

background that used literary criticism to understand the Bible forms.

It became influential in moving biblical criticism from a historical to a

literary focus.

By 1974, the two methodologies being used in literary criticism were

rhetorical analysis and

structuralism.

Rhetorical analysis divides a passage into units, observes how a single

unit shifts or breaks, taking special note of poetic devices, meter,

parallelism, word play and so on. It then charts the writer's thought

progression from one unit to the next, and finally, assembles the data

in an attempt to explain the author's intentions behind the piece.

Structuralism looks at the language to discern "layers of meaning" with

the goal of uncovering a work's "deep structures": the premises as well

as the purposes of the author.

In 1981 literature scholar

Robert Alter

also contributed to the development of biblical literary criticism by

publishing an influential analysis of biblical themes from a literary

perspective. The 1980s saw the rise of

formalism, which focuses on plot, structure, character and themes.

Reader-response criticism, which focuses on the reader rather than the author, was put forward by the Old Testament scholar

David M. Gunn in 1987.

New Testament scholar

Donald Guthrie

highlights a flaw in the literary critical approach to the Gospels. The

genre of the Gospels has not been fully determined. No conclusive

evidence has yet been produced to settle the question of genre, and

without genre, no adequate parallels can be found, and without parallels

"it must be considered to what extent the principles of literary

criticism are applicable."

The validity of using the same critical methods for novels and for the

Gospels, without the assurance the Gospels are actually novels, must be

questioned.

Types of literary criticism

Canonical criticism has both theological and literary roots. Its

origins are found in the Church's views of scripture as sacred as well

as in the literary critics who began to influence biblical scholarship

in the 1940s and 1950s. Canonical criticism responded to two things: 1)

the sense that biblical criticism had obscured the meaning and authority

of the canon of scripture; and 2) the fundamentalism in the Christian

Church that had arisen in America in the 1920s and 1930s. Canonical

criticism does not reject historical criticism and sociological

analysis, but considers them secondary in importance.

Canonical critics believe the texts should be treated with respect as the canon of a believing community.

Canonical critics use the tools of biblical criticism to study the books of the Bible, but approach the books as whole units.

They take the books as finished works and treat each book as a unity,

instead of taking them apart and focusing on isolated pieces. This

begins from the position that scripture contains within it what is

needed to understand it, rather than being understandable only as the

product of a historically determined process.

Canonical criticism helped literary criticism move biblical studies in

a new direction by focusing on the text rather than the author. It uses

the text itself, the needs of the communities addressed by those texts,

and the interpretation likely to have been formed originally to meet

those needs. The canonical critic then relates this to the overall

canon. Canonical criticism is associated with

Brevard S. Childs (1923–2007), though he declined to use the term.

James Muilenburg (1896–1974) is often referred to as "the prophet of rhetorical criticism".

A product of the 1960s, rhetorical criticism seeks to understand text

type, as does form criticism, but moves beyond form criticism by looking

into the inner theological meaning the author was trying to

communicate. The rhetorical scholar

Sonja K. Foss

says there are ten methods of practicing rhetorical criticism, but each

focuses on three dimensions of rhetoric: the authors, what they use to

communicate, and what they are trying to communicate.

Rhetorical criticism is the systematic effort to understand the message

being communicated in a focused and conscious manner. Biblical

rhetorical criticism asks how hearing the texts impacted the audience.

It attempts to discover and evaluate the rhetorical devices, language,

and methods of communication used within the texts to accomplish the

goals of those texts.

Phyllis Trible,

a student of Muilenburg, has become one of the "leading practitioners

of rhetorical criticism" and is known for her detailed literary analysis

and her

feminist critique of biblical interpretation.

Within narrative criticism, critics approach scripture as story.

Narrative criticism began being used to study the New Testament in the

1970s, and a decade later, study also included the Old Testament. However, the first time a published approach was labeled

narrative criticism was in 1980, in the article "Narrative Criticism and the Gospel of Mark," written by Bible scholar David Rhoads. Narrative criticism has its foundations in form criticism, but it is

not a historical discipline. It is purely literary. Historical critics

began to recognize the Bible was not being studied in the manner other

ancient writings were studied, and they began asking if these texts

should be understood on their own terms before being used as evidence of

something else like history.

It is now accepted as "axiomatic in literary circles that the meaning

of literature transcends the historical intentions of the author."

Narrative criticism embraces the textual unity of canonical criticism,

while admitting the existence of the sources and redactions of

historical criticism. Narrative critics choose to focus on the artistic

weaving of the biblical texts into a sustained narrative picture.

The literary scholar Steven Weitzman (1892–1957) has argued that

"narrative economy" (omitting comments about the thoughts or emotional

state of a character) and "narrative unity" are what make the text a

"work of art". Narrative critics encourage the "implied reader" to see biblical

characters as literary figures, observe textual unity, the importance of

the narrator, "implied"

authorial intent, and to be aware that a narrative can be interpreted in multiple ways.

This perspective is key, Auerbach says: "Since so much in [Bible

stories] is dark and incomplete, and since the reader knows that God is a

hidden god, [the reader's] effort to interpret it constantly finds

something new to feed on... there is no end for interpretation."

Life of Jesus research

The Quest for the historical Jesus, also known as life of Jesus

research, is an area of biblical criticism that seeks to reconstruct the

life and teachings of

Jesus of Nazareth by

critical historical methods.

The quest began with the posthumous publication of Hermann Reimarus'

effort to reconstruct an "authentic" historical picture of Jesus instead

of a theological one. The quest was a product of the

Enlightenment skepticism of the late eighteenth century and produced a stark division between history and theology. The study flourished in the nineteenth century, making its mark in the theology of the

German Protestant liberals.

They saw the purpose of a historically true life of Jesus as a critical

force that functioned theologically against the high Christology

established by Roman Catholicism centuries before.

After Albert Schweitzer's

Von Reimarus zu Wrede was published as

The Quest of the Historical Jesus in 1910, its title provided the label for the field of study for the next eighty years.

Interest languished in the early twentieth century, but revived in the

1950s, with some scholars asserting there have been three distinct

quests. However, Bible scholar Stanley Porter asserts that there has

been one fluctuating, but still continuous, multifaceted quest for the

historical Jesus from the beginning. By the end of the twentieth century, a more trusting attitude towards

the historical reliability of sources gradually replaced Enlightenment

skepticism. E. P. Sanders explains that, because of the desire to know

everything about Jesus, including his thoughts and motivations, and

because there are such varied conclusions about him, it seems to many

scholars that it is impossible to be certain about anything. Yet

according to Sanders, "we know a lot" about Jesus. Sanders' view

characterizes most contemporary studies.

Reflecting this shift, the phrase "quest for the historical Jesus" has largely been replaced by "life of Jesus research".

The lasting achievement of the contemporary quest has been sensitizing scholars to Jesus' Jewish environment.

Contemporary developments

Responses

At first, biblical historical criticism and its deductions and

implications were so unpopular outside liberal Protestant scholarship it

created a schism in Protestantism. The

American fundamentalist movement of the 1920s and 1930s began, at least partly, as a response to

nineteenth century liberalism.

Some fundamentalists believed liberal critics had invented an entirely

new religion "completely at odds with the Christian faith". However, there were also conservative Protestants who accepted it.

William Robertson Smith (1846–1894) is an example of a nineteenth century

evangelical who believed historical criticism was a legitimate outgrowth of the

Protestant Reformation's

focus on the biblical text. He saw it as a "necessary tool to enable

intelligent churchgoers" to understand the Bible, and was a pioneer in

establishing the final form of the

supplementary hypothesis of the documentary hypothesis. A similar view was later advocated by the

Primitive Methodist biblical scholar

A. S. Peake (1865–1929).

Other evangelical Protestant scholars such as

Edwin M. Yamauchi,

Paul R. House, and

Daniel B. Wallace have continued the tradition of conservatives contributing to critical scholarship.

M.-J. Lagrange was instrumental in helping Catholicism accept biblical criticism.

Monseigneur

Joseph G. Prior

says, "Catholic studies in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries

avoided the use of critical methodology because of its rationalism [so

there was] no significant Catholic involvement in biblical scholarship

until the nineteenth century."

In 1890, the French Dominican

Marie-Joseph Lagrange

(1855–1938) established the École Biblique in Jerusalem to encourage

study of the Bible using the historical-critical method. Two years later

he funded a journal, spoke thereafter at various conferences, wrote

Bible commentaries that incorporated textual critical work of his own,

did pioneering work on biblical genres and forms, and laid the path to

overcoming resistance to the historical-critical method among his fellow

scholars.

However,

Pope Leo XIII (1810–1903) condemned biblical scholarship based on rationalism in his encyclical letter

Providentissimus Deus ("On the Study of Holy Scripture") on 18 November 1893. It declared that no

exegete was allowed to interpret a text to contradict church doctrine.

Later, in 1943 on the fiftieth anniversary of the

Providentissimus Deus, Pope Pius XII issued the papal encyclical

Divino afflante spiritu

('Inspired by the Holy Spirit') sanctioning historical criticism,

opening a new epoch in Catholic critical scholarship. The Jesuit

Augustin Bea (1881–1968) had played a vital part in its publication.

This tradition is continued by Catholic scholars such as

John P. Meier,

Bernard Orchard,

and

Reginald C. Fuller.

Hebrew Bible scholar

Marvin A. Sweeney

argues that some Christian theological assumptions within biblical

criticism have reached anti-semitic conclusions. This has discouraged

Jews from engaging in biblical criticism.

Hebrew Bible scholar

Jon D. Levenson described how some Jewish scholars, such as

rabbinicist Solomon Schechter (b. 1903),

saw biblical criticism of the Pentateuch as a threat to Jewish

identity. The growing anti-semitism in Germany of the late nineteenth

and early twentieth centuries, the perception that higher criticism was

an entirely Christian pursuit, and the sense many Bible critics were not

impartial academics but were proponents of

supersessionism, prompted Schechter to describe "

Higher Criticism as

Higher Anti-semitism".

Professor of Hebrew Bible Baruch J. Schwartz states that these

perceptions delayed Jewish scholars from entering the field of biblical

criticism.

These problems began to be corrected in the modern era. The

Holocaust

led to Christian theologians rethinking ways to relate to Judaism, and

the entry of Jewish scholars into academic departments from which they

had formerly been excluded aided that process.

The first historical-critical Jewish scholar of Pentateuchal studies was

M. M. Kalisch in the nineteenth century.

In the early twentieth century, historical criticism of the Pentateuch became mainstream among Jewish scholars. In 1905, Rabbi David C. Hoffman wrote an extensive, two-volume,

philologically based critique of the

Wellhausen theory, which supported

Jewish orthodoxy. Bible professor Benjamin D. Sommer says it is "among the most precise and detailed commentaries on the legal texts [

Leviticus and

Deuteronomy] ever written."

Yehezkel Kaufmann was the first Jewish scholar to appreciate fully the import of higher criticism.

Mordechai Breuer, who branches out beyond most Jewish

exegesis

and explores the implications of historical criticism for multiple

subjects, is an example of a contemporary Jewish biblical critical

scholar.

Contemporary methods

Socio-scientific criticism is part of the wider trend in biblical criticism reflecting interdisciplinary methods and diversity. It grew out of form criticism's

Sitz im Leben

and the sense that historical form criticism had failed to adequately

analyze the social and anthropological contexts which form criticism

claimed had formed the texts. Using the perspectives, theories, models,

and research of the social sciences to determine what social norms may

have influenced the growth of biblical tradition, it is similar to

historical biblical criticism in its goals and methods. It has less in

common with literary critical approaches. It analyzes the social and

cultural dimensions of the text and its environmental context.

In the 1940s and 1950s the term

postmodern came into use to signify a rejection of modern conventions. Many of these early postmodernist views came from France following World War II. Postmodernism has been associated with

Karl Marx,

Sigmund Freud,

radical politics, and arguments against metaphysics and ideology.

Soulen and Soulen quote French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard saying

"I define postmodernism as incredulity toward meta-narratives."

Biblical scholar

A. K. M. Adam says postmodernism is not so much a method as a stance.

It has three general features: 1) it denies any privileged starting

point for truth; 2) it is critical of theories that attempt to explain

the "totality of reality"; and 3) it attempts to show that all

ideals are grounded in ideological, economic or political self-interest.

Postmodernists are suspicious of traditional theology and the

neutrality of reason, and emphasize relativism and indeterminacy of

texts. In textual criticism, postmodernists reject the idea of a sacred

text, treating all manuscripts as equally valuable.

Feminist criticism is an aspect of the

feminist theology movement which began in the 1960s and 1970s in the context of Second Wave feminism in the United States.

Feminist theology has been ground-breaking in biblical criticism,

disrupting the long-standing exclusivity of Christian theology as

Western.

In the 1980s, Phyllis Trible and

Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza

reframed biblical criticism itself by challenging the supposed

disinterest and objectivity it claimed for itself and exposing how

ideological-theological stances had played a critical role in

interpretation. Feminist biblical interpreters are characterized by the claim that

classical models of understanding are patriarchal and therefore that

makes it impossible for those models to identify the true contribution

of women. Feminist criticism embraces a

reader-response approach to the text that includes an attitude of "dissent" or "resistance."

Post-critical biblical interpretation shares the postmodernist suspicion of non-neutrality of traditional approaches, but is not hostile toward theology.

It begins with the understanding that historical biblical criticism's

focus on historicity produced a distinction between the meaning of what

the text says and what it is about (what it references). This produced

doubts about the text's veracity. The theologian

Hans Frei

writes that what he refers to as the "realistic narratives" of

literature, including the Bible, don't allow for such separation. Subject matter is identical to verbal meaning and is found in plot and nowhere else.

"As Frei puts it, scripture 'simultaneously depicts and renders the

reality (if any) of what it talks about'; its subject matter is

'constituted by, or identical with, its narrative'."

Psychological biblical criticism

applies psychology to biblical texts; it was not until the 1990s that

it began to have an influence among the new critical approaches.

Bible scholar Wayne Rollins says the goal of a psychological critical

approach is to find expressions of the human psyche in the biblical

texts.

It can be used in both a historical and a literary manner to examine

the psychological dimensions of scripture through the use of the

behavioral sciences.