| Delayed sleep phase disorder | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Delayed sleep–wake phase disorder, delayed sleep phase syndrome, delayed sleep phase type |

| |

| Comparison of standard (green) and DSPD (blue) circadian rhythms | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, sleep medicine |

Delayed sleep phase disorder (DSPD), more often known as delayed sleep phase syndrome and also as delayed sleep–wake phase disorder, is a chronic dysregulation of a person's circadian rhythm (biological clock), compared to those of the general population and societal norms. The disorder affects the timing of sleep, peak period of alertness, the core body temperature, rhythm, hormonal as well as other daily cycles. People with DSPD generally fall asleep some hours after midnight and have difficulty waking up in the morning. People with DSPD probably have a circadian period significantly longer than 24 hours. Depending on the severity, the symptoms can be managed to a greater or lesser degree, but no cure is known, and research suggests a genetic origin for the disorder.

Affected people often report that while they do not get to sleep until the early morning, they do fall asleep around the same time every day. Unless they have another sleep disorder such as sleep apnea in addition to DSPD, patients can sleep well and have a normal need for sleep. However, they find it very difficult to wake up in time for a typical school or work day. If they are allowed to follow their own schedules, e.g. sleeping from 4:00 am to 1:00 pm, their sleep is improved and they may not experience excessive daytime sleepiness. Attempting to force oneself onto daytime society's schedule with DSPD has been compared to constantly living with jet lag; DSPD has been called "social jet lag".

Researchers in 2017 linked DSPD to at least one genetic mutation. The syndrome usually develops in early childhood or adolescence. An adolescent version may disappear in late adolescence or early adulthood; otherwise, DSPD is a lifelong condition. The best estimate of prevalence among adults is 0.13–0.17% (1 in 600). Prevalence among adolescents is as much as 7–16%.

DSPD was first formally described in 1981 by Elliot D. Weitzman and others at Montefiore Medical Center.[9] It is responsible for 7–13% of patient complaints of chronic insomnia. However, since many doctors are unfamiliar with the condition, it often goes untreated or is treated inappropriately; DSPD is often misdiagnosed as primary insomnia or as a psychiatric condition. DSPD can be treated or helped in some cases by careful daily sleep practices, morning light therapy, evening dark therapy, earlier exercise and meal times, and medications such as aripiprazole, melatonin, and modafinil; melatonin is a natural neurohormone partly responsible for the human body clock. At its most severe and inflexible, DSPD is a disability. A chief difficulty of treating DSPD is in maintaining an earlier schedule after it has been established, as the patient's body has a strong tendency to reset the sleeping schedule to its intrinsic late times. People with DSPD may improve their quality of life by choosing careers that allow late sleeping times, rather than forcing themselves to follow a conventional 9-to-5 work schedule.

Presentation

Comorbidity

Depression

In the DSPD cases reported in the literature, about half of the patients have suffered from clinical depression or other psychological problems, about the same proportion as among patients with chronic insomnia. According to the ICSD:

Although some degree of psychopathology is present in about half of adult patients with DSPD, there appears to be no particular psychiatric diagnostic category into which these patients fall. Psychopathology is not particularly more common in DSPD patients compared to patients with other forms of "insomnia." ... Whether DSPD results directly in clinical depression, or vice versa, is unknown, but many patients express considerable despair and hopelessness over sleeping normally again.

A direct neurochemical relationship between sleep mechanisms and depression is another possibility.

It is conceivable that DSPD has a role in causing depression because it can be such a stressful and misunderstood disorder. A 2008 study from the University of California, San Diego found no association of bipolar disorder (history of mania) with DSPD, and it states that

there may be behaviorally-mediated mechanisms for comorbidity between DSPD and depression. For example, the lateness of DSPD cases and their unusual hours may lead to social opprobrium and rejection, which might be depressing.

The fact that half of DSPD patients are not depressed indicates that DSPD is not merely a symptom of depression. Sleep researcher Michael Terman has suggested that those who follow their internal circadian clocks may be less likely to suffer from depression than those trying to live on a different schedule.

DSPD patients who also suffer from depression may be best served by seeking treatment for both problems. There is some evidence that effectively treating DSPD can improve the patient's mood and make antidepressants more effective.

Vitamin D deficiency has been linked to depression. As it is a condition which comes from lack of exposure to sunlight, anyone who does not get enough sunlight exposure during daylight hours (about 20 to 30 minutes three times a week, depending on skin tone, latitude, and the time of year) could be at risk, without adequate dietary sources or supplements.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

DSPD is genetically linked to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder by findings of polymorphism in genes in common between those apparently involved in ADHD and those involved in the circadian rhythm and a high proportion of DSPD among those with ADHD.

Overweight

A 2019 study from Boston showed a relationship of evening chronotypes and greater social jet lag with greater body weight / adiposity in adolescent girls, but not boys, independent of sleep duration.

Obsessive–compulsive disorder

Persons with obsessive–compulsive disorder are also diagnosed with DSPD at a much higher rate than the general public.

Mechanism

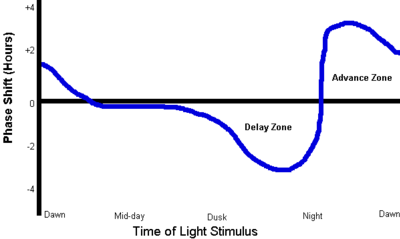

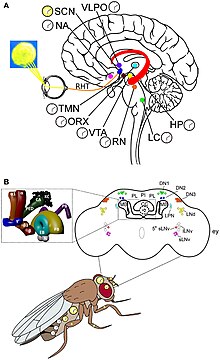

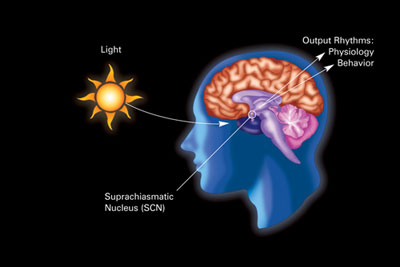

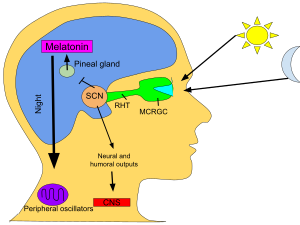

DSPD is a disorder of the body's timing system—the biological clock. Individuals with DSPD might have an unusually long circadian cycle, might have a reduced response to the resetting effect of daylight on the body clock, and/or may respond overly to the delaying effects of evening light and too little to the advancing effect of light earlier in the day. In support of the increased sensitivity to evening light hypothesis, "the percentage of melatonin suppression by a bright light stimulus of 1,000 lux administered 2 hours prior to the melatonin peak has been reported to be greater in 15 DSPD patients than in 15 controls."

The altered phase relationship between the timing of sleep and the circadian rhythm of body core temperature has been reported previously in DSPD patients studied in entrained conditions. That such an alteration has also been observed in temporal isolation (free-running clock) supports the notion that the etiology of DSPD goes beyond simply a reduced capacity to achieve and maintain the appropriate phase relationship between sleep timing and the 24-hour day. Rather, the disorder may also reflect a fundamental inability of the endogenous circadian timing system to maintain normal internal phase relationships among physiological systems, and to properly adjust those internal relationships within the confines of the 24-hour day. In normal subjects, the phase relationship between sleep and temperature changes in temporal isolation relative to that observed under entrained conditions: in isolation, tmin tends to occur toward the beginning of sleep, whereas under entrained conditions, tmin occurs toward the end of the sleep period—a change in phase angle of several hours; DSPD patients may have a reduced capacity to achieve such a change in phase angle in response to entrainment.

Possibly as a consequence of these altered internal phase relationships, that the quality of sleep in DSPD may be substantially poorer than that of normal subjects, even when bedtimes and wake times are self-selected. A DSPD subject exhibited an average sleep onset latency twice that of the 3 control subjects and almost twice the amount of wakefulness after sleep onset (WASO) as control subjects, resulting in significantly poorer sleep efficiency. Also, the temporal distribution of slow wave sleep was significantly altered in the DSPD subject. This finding may suggest that, in addition to abnormal circadian clock function, DSPD may be characterized by alteration(s) in the homeostatic regulation of sleep, as well. Specifically, the rate with which Process S is depleted during sleep may be slowed. This could, conceivably, contribute to the excessive sleep inertia upon awakening that is often reported by DSPD sufferers. It has also been hypothesized that, due to the altered phase angle between sleep and temperature observed in DSPD, and the tendency for longer sleep periods, these individuals may simply sleep through the phase-advance portion of the light PRC. Though quite limited in terms of the total number of DSPD patients studied, such data seem to contradict the notion that DSPD is merely a disorder of sleep timing, rather than a disorder of the sleep system itself.

People with normal circadian systems can generally fall asleep quickly at night if they slept too little the night before. Falling asleep earlier will in turn automatically help to advance their circadian clocks due to decreased light exposure in the evening. In contrast, people with DSPD have difficulty falling asleep before their usual sleep time, even if they are sleep-deprived. Sleep deprivation does not reset the circadian clock of DSPD patients, as it does with normal people.

People with the disorder who try to live on a normal schedule cannot fall asleep at a "reasonable" hour and have extreme difficulty waking because their biological clocks are not in phase with that schedule. Non-DSPD people who do not adjust well to working a night shift have similar symptoms (diagnosed as shift-work sleep disorder).

In most cases, it is not known what causes the abnormality in the biological clocks of DSPD patients. DSPD tends to run in families, and a growing body of evidence suggests that the problem is associated with the hPer3 (human period 3) gene and CRY1 gene. There have been several documented cases of DSPD and non-24-hour sleep–wake disorder developing after traumatic head injury. There have been cases of DSPD developing into non-24-hour sleep–wake disorder, a severe and debilitating disorder in which the individual sleeps later each day.

Diagnosis

DSPD is diagnosed by a clinical interview, actigraphic monitoring, and/or a sleep diary kept by the patient for at least two weeks. When polysomnography is also used, it is primarily for the purpose of ruling out other disorders such as narcolepsy or sleep apnea.

DSPD is frequently misdiagnosed or dismissed. It has been named as one of the sleep disorders most commonly misdiagnosed as a primary psychiatric disorder. DSPD is often confused with: psychophysiological insomnia; depression; psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, ADHD or ADD; other sleep disorders; or school refusal. Practitioners of sleep medicine point out the dismally low rate of accurate diagnosis of the disorder, and have often asked for better physician education on sleep disorders.

Definition

According to the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Revised (ICSD-R, 2001), the circadian rhythm sleep disorders share a common underlying chronophysiologic basis:

The major feature of these disorders is a misalignment between the patient's sleep-wake pattern and the pattern that is desired or regarded as the societal norm... In most circadian rhythm sleep disorders, the underlying problem is that the patient cannot sleep when sleep is desired, needed or expected.

Incorporating minor updates (ICSD-3, 2014), the diagnostic criteria for delayed sleep phase disorder are:

- An intractable delay in the phase of the major sleep period occurs in relation to the desired clock time, as evidenced by a chronic or recurrent (for at least three months) complaint of inability to fall asleep at a desired conventional clock time together with the inability to awaken at a desired and socially acceptable time.

- When not required to maintain a strict schedule, patients exhibit improved sleep quality and duration for their age and maintain a delayed phase of entrainment to local time.

- Patients have little or no reported difficulty in maintaining sleep once sleep has begun.

- Patients have a relatively severe to absolute inability to advance the sleep phase to earlier hours by enforcing conventional sleep and wake times.

- Sleep–wake logs and/or actigraphy monitoring for at least two weeks document a consistent habitual pattern of sleep onsets, usually later than 2 am, and lengthy sleeps.

- Occasional noncircadian days may occur (i.e., sleep is "skipped" for an entire day and night plus some portion of the following day), followed by a sleep period lasting 12 to 18 hours.

- The symptoms do not meet the criteria for any other sleep disorder causing inability to initiate sleep or excessive sleepiness.

- If one of the following laboratory methods is used, it must demonstrate a significant delay in the timing of the habitual sleep period: 1) 24-hour polysomnographic monitoring (or two consecutive nights of polysomnography and an intervening multiple sleep latency test), 2) Continuous temperature monitoring showing that the time of the absolute temperature nadir is delayed into the second half of the habitual (delayed) sleep episode.

Some people with the condition adapt their lives to the delayed sleep phase, avoiding morning business hours as much as possible. The ICSD's severity criteria are:

- Mild: Two-hour delay (relative to the desired sleep time) associated with little or mild impairment of social or occupational functioning.

- Moderate: Three-hour delay associated with moderate impairment.

- Severe: Four-hour delay associated with severe impairment.

Some features of DSPD which distinguish it from other sleep disorders are:

- People with DSPD have at least a normal—and often much greater than normal—ability to sleep during the morning, and sometimes in the afternoon as well. In contrast, those with chronic insomnia do not find it much easier to sleep during the morning than at night.

- People with DSPD fall asleep at more or less the same time every night, and sleep comes quite rapidly if the person goes to bed near the time they usually fall asleep. Young children with DSPD resist going to bed before they are sleepy, but the bedtime struggles disappear if they are allowed to stay up until the time they usually fall asleep.

- DSPD patients usually sleep well and regularly when they can follow their own sleep schedule, e.g., on weekends and during vacations.

- DSPD is a chronic condition. Symptoms must have been present for at least three months before a diagnosis of DSPD can be made.

Often people with DSPD manage only a few hours sleep per night during the working week, then compensate by sleeping until the afternoon on weekends. Sleeping late on weekends, and/or taking long naps during the day, may give people with DSPD relief from daytime sleepiness but may also perpetuate the late sleep phase.

People with DSPD can be called "night owls". They feel most alert and say they function best and are most creative in the evening and at night. People with DSPD cannot simply force themselves to sleep early. They may toss and turn for hours in bed, and sometimes not sleep at all, before reporting to work or school. Less-extreme and more-flexible night owls are within the normal chronotype spectrum.

By the time those who have DSPD seek medical help, they usually have tried many times to change their sleeping schedule. Failed tactics to sleep at earlier times may include maintaining proper sleep hygiene, relaxation techniques, early bedtimes, hypnosis, alcohol, sleeping pills, dull reading, and home remedies. DSPD patients who have tried using sedatives at night often report that the medication makes them feel tired or relaxed, but that it fails to induce sleep. They often have asked family members to help wake them in the morning, or they have used multiple alarm clocks. As the disorder occurs in childhood and is most common in adolescence, it is often the patient's parents who initiate seeking help, after great difficulty waking their child in time for school.

The current formal name established in the third edition of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-3) is delayed sleep-wake phase disorder. Earlier, and still common, names include delayed sleep phase disorder (DSPD), delayed sleep phase syndrome (DSPS), and circadian rhythm sleep disorder, delayed sleep phase type (DSPT).

Management

Treatment, a set of management techniques, is specific to DSPD. It is different from treatment of insomnia, and recognizes the patients' ability to sleep well on their own schedules, while addressing the timing problem. Success, if any, may be partial; for example, a patient who normally awakens at noon may only attain a wake time of 10 or 10:30 with treatment and follow-up. Being consistent with the treatment is paramount.

Before starting DSPD treatment, patients are often asked to spend at least a week sleeping regularly, without napping, at the times when the patient is most comfortable. It is important for patients to start treatment well-rested.

Non-pharmacological

One treatment strategy is light therapy (phototherapy), with either a bright white lamp providing 10,000 lux at a specified distance from the eyes or a wearable LED device providing 350–550 lux at a shorter distance. Sunlight can also be used. The light is typically timed for 30–90 minutes at the patient's usual time of spontaneous awakening, or shortly before (but not long before), which is in accordance with the phase response curve (PRC) for light. Only experimentation, preferably with specialist help, will show how great an advance is possible and comfortable. For maintenance, some patients must continue the treatment indefinitely; some may reduce the daily treatment to 15 minutes; others may use the lamp, for example, just a few days a week or just every third week. Whether the treatment is successful is highly individual. Light therapy generally requires adding some extra time to the patient's morning routine. Patients with a family history of macular degeneration are advised to consult with an eye doctor. The use of exogenous melatonin administration (see below) in conjunction with light therapy is common.

Light restriction in the evening, sometimes called darkness therapy or scototherapy, is another treatment strategy. Just as bright light upon awakening should advance one's sleep phase, bright light in the evening and night delays it (see the PRC). It is suspected that DSPD patients may be overly sensitive to evening light. The photopigment of the retinal photosensitive ganglion cells, melanopsin, is excited by light mainly in the blue portion of the visible spectrum (absorption peaks at ~480 nanometers).

A formerly popular treatment, phase delay chronotherapy, is intended to reset the circadian clock by manipulating bedtimes. It consists of going to bed two or more hours later each day for several days until the desired bedtime is reached, and it often must be repeated every few weeks or months to maintain results. Its safety is uncertain, notably because it has led to the development of non-24-hour sleep-wake rhythm disorder, a much more severe disorder.

A modified chronotherapy is called controlled sleep deprivation with phase advance, SDPA. One stays awake one whole night and day, then goes to bed 90 minutes earlier than usual and maintains the new bedtime for a week. This process is repeated weekly until the desired bedtime is reached.

Earlier exercise and meal times can also help promote earlier sleep times.

Pharmacological

Aripiprazole (brand name Abilify) is an atypical antipsychotic that has been shown to be effective in treating DSPD by advancing sleep onset, sleep midpoint, and sleep offset at relatively low doses.

Melatonin taken an hour or so before the usual bedtime may induce sleepiness. Taken this late, it does not, of itself, affect circadian rhythms, but a decrease in exposure to light in the evening is helpful in establishing an earlier pattern. In accordance with its phase response curve (PRC), a very small dose of melatonin can also, or instead, be taken some hours earlier as an aid to resetting the body clock; it must then be small enough not to induce excessive sleepiness.

Side effects of melatonin may include sleep disturbance, nightmares, daytime sleepiness, and depression, though the current tendency to use lower doses has decreased such complaints. Large doses of melatonin can even be counterproductive: Lewy et al. provide support to "the idea that too much melatonin may spill over onto the wrong zone of the melatonin phase-response curve." The long-term effects of melatonin administration have not been examined. In some countries, the hormone is available only by prescription or not at all. In the United States and Canada, melatonin is on the shelf of most pharmacies and herbal stores. The prescription drug Rozerem (ramelteon) is a melatonin analogue that selectively binds to the melatonin MT1 and MT2 receptors and, hence, has the possibility of being effective in the treatment of DSPD.

A review by the US Department of Health and Human Services found little difference between melatonin and placebo for most primary and secondary sleep disorders. The one exception, where melatonin is effective, is the "circadian abnormality" DSPD. Another systematic review found inconsistent evidence for the efficacy of melatonin in treating DSPD in adults, and noted that it was difficult to draw conclusions about its efficacy because many recent studies on the subject were uncontrolled.

Modafinil (brand name Provigil) is a stimulant approved in the US for treatment of shift-work sleep disorder, which shares some characteristics with DSPD. A number of clinicians prescribe it for DSPD patients, as it may improve a sleep-deprived patient's ability to function adequately during socially desirable hours. It is generally not recommended to take modafinil after noon; modafinil is a relatively long-acting drug with a half-life of 15 hours, and taking it during the later part of the day can make it harder to fall asleep at bedtime.

Vitamin B12 was, in the 1990s, suggested as a remedy for DSPD, and is still recommended by some sources. Several case reports were published. However, a review for the American Academy of Sleep Medicine in 2007 concluded that no benefit was seen from this treatment.

Prognosis

Risk of relapse

A strict schedule and good sleep hygiene are essential in maintaining any good effects of treatment. With treatment, some people with mild DSPD may sleep and function well with an earlier sleep schedule. Caffeine and other stimulant drugs to keep a person awake during the day may not be necessary and should be avoided in the afternoon and evening, in accordance with good sleep hygiene. A chief difficulty of treating DSPD is in maintaining an earlier schedule after it has been established. Inevitable events of normal life, such as staying up late for a celebration or deadline, or having to stay in bed with an illness, tend to reset the sleeping schedule to its intrinsic late times.

Long-term success rates of treatment have seldom been evaluated. However, experienced clinicians acknowledge that DSPD is extremely difficult to treat. One study of 61 DSPD patients, with average sleep onset at about 3:00 am and average waking time of about 11:30 am, was followed with questionnaires to the subjects after a year. Good effect was seen during the six-week treatment with a large daily dose of melatonin. After ceasing melatonin use over 90% had relapsed to pre-treatment sleeping patterns within the year, 29% reporting that the relapse occurred within one week. The mild cases retained changes significantly longer than the severe cases.

Adaptation to late sleeping times

Working the evening or night shift, or working at home, makes DSPD less of an obstacle for some. Many of these people do not describe their pattern as a "disorder". Some DSPD individuals nap, even taking 4–5 hours of sleep in the morning and 4–5 in the evening. DSPD-friendly careers can include security work, the entertainment industry, hospitality work in restaurants, theaters, hotels or bars, call center work, manufacturing, healthcare or emergency medicine, commercial cleaning, taxi or truck driving, the media, and freelance writing, translation, IT work, or medical transcription. Some other careers that have an emphasis on early morning work hours, such as bakers, coffee baristas, pilots and flight crews, teachers, mail carriers, waste collection, and farming, can be particularly difficult for people who naturally sleep later than is typical. Some careers, such as over-the-road truck drivers, firefighters, law enforcement, nursing, can be suitable for both people with delayed sleep phase syndrome and people with the opposite condition, advanced sleep phase disorder, as these workers are needed both very early in the morning and also late at night.

Some people with the disorder are unable to adapt to earlier sleeping times, even after many years of treatment. Sleep researchers Dagan and Abadi have proposed that the existence of untreatable cases of DSPD be formally recognized as a "sleep-wake schedule disorder (SWSD) disability", an invisible disability.

Rehabilitation for DSPD patients includes acceptance of the condition and choosing a career that allows late sleeping times or running a home business with flexible hours. In a few schools and universities, students with DSPD have been able to arrange to take exams at times of day when their concentration levels may be good.

Patients suffering from SWSD disability should be encouraged to accept the fact that they suffer from a permanent disability, and that their quality of life can only be improved if they are willing to undergo rehabilitation. It is imperative that physicians recognize the medical condition of SWSD disability in their patients and bring it to the notice of the public institutions responsible for vocational and social rehabilitation.

In the United States, the Americans with Disabilities Act requires that employers make reasonable accommodations for employees with sleeping disorders. In the case of DSPD, this may require that the employer accommodate later working hours for jobs normally performed on a "9 to 5" work schedule. The statute defines "disability" as a "physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities", and Section 12102(2)(a) itemizes sleeping as a "major life activity".

Impact on patients

Lack of public awareness of the disorder contributes to the difficulties experienced by people with DSPD, who are commonly stereotyped as undisciplined or lazy. Parents may be chastised for not giving their children acceptable sleep patterns, and schools and workplaces rarely tolerate chronically late, absent, or sleepy students and workers, failing to see them as having a chronic illness.

By the time DSPD sufferers receive an accurate diagnosis, they often have been misdiagnosed or labelled as lazy and incompetent workers or students for years. Misdiagnosis of circadian rhythm sleep disorders as psychiatric conditions causes considerable distress to patients and their families, and leads to some patients being inappropriately prescribed psychoactive drugs. For many patients, diagnosis of DSPD is itself a life-changing breakthrough.

As DSPD is so little-known and so misunderstood, peer support may be important for information, self-acceptance, and future research studies.

People with DSPD who force themselves to follow a normal 9–5 workday "are not often successful and may develop physical and psychological complaints during waking hours, e.g., sleepiness, fatigue, headache, decreased appetite, or depressed mood. Patients with circadian rhythm sleep disorders often have difficulty maintaining ordinary social lives, and some of them lose their jobs or fail to attend school."

Epidemiology

There have been several studies that have attempted to estimate the prevalence of DSPD. Results vary due to differences in methods of data collection and diagnostic criteria. A particular issue is where to draw the line between extreme evening chronotypes and clinical DSPD. Using the ICSD-1 diagnostic criteria (current edition ICSD-3) a study by telephone questionnaire in 1993 of 7,700 randomly selected adults (aged 18–67) in Norway estimated the prevalence of DSPD at 0.17%. A similar study in 1999 of 1,525 adults (aged 15–59) in Japan estimated its prevalence at 0.13%. A somewhat higher prevalence of 0.7% was found in a 1995 San Diego study. A 2014 study of 9100 New Zealand adults (age 20–59) using a modified version of the Munich Chronotype Questionnaire found a DSPD prevalence of 1.5% to 8.9% depending on the strictness of the definition used. A 2002 study of older adults (age 40–65) in San Diego found 3.1% had complaints of difficulty falling asleep at night and waking in the morning, but did not apply formal diagnostic criteria. Actimetry readings showed only a small proportion of this sample had delays of sleep timing.

A marked delay of sleep patterns is a normal feature of the development of adolescent humans. According to Mary Carskadon, both circadian phase and homeostasis (the accumulation of sleep pressure during the wake period) contribute to a DSPD-like condition in post-pubertal as compared to pre-pubertal youngsters. Adolescent sleep phase delay "is present both across cultures and across mammalian species" and "it seems to be related to pubertal stage rather than age." As a result, diagnosable DSPD is much more prevalent among adolescents. with estimates ranging from 3.4% to 8.4% among high school students.