| Homo | |

|---|---|

| |

| Forensic reconstruction of an adult female Homo erectus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Genus: | Homo Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Type species | |

| Homo sapiens

Linnaeus, 1758

| |

| Species | |

Homo erectus appeared about two million years ago and, in several early migrations, it spread throughout Africa (where it is dubbed Homo ergaster) and Eurasia. It was likely the first human species to live in a hunter-gatherer society and to control fire. An adaptive and successful species, Homo erectus persisted for more than a million years, and gradually diverged into new species by around 500,000 years ago.

Homo sapiens (anatomically modern humans) emerges close to 300,000 to 200,000 years ago, most likely in Africa, and Homo neanderthalensis emerges at around the same time in Europe and Western Asia. H. sapiens dispersed from Africa in several waves, from possibly as early as 250,000 years ago, and certainly by 130,000 years ago, the so-called Southern Dispersal beginning about 70,000 years ago leading to the lasting colonisation of Eurasia and Oceania by 50,000 years ago. Both in Africa and Eurasia, H. sapiens met with and interbred with archaic humans. Separate archaic (non-sapiens) human species are thought to have survived until around 40,000 years ago (Neanderthal extinction), with possible late survival of hybrid species as late as 12,000 years ago (Red Deer Cave people).

Among extant populations of Homo sapiens, the deepest temporal division is found in the San people of Southern Africa, estimated at close to 130,000 years.

Names and taxonomy

Evolutionary tree chart emphasizing the subfamily Homininae and the tribe Hominini. After diverging from the line to Ponginae the early Homininae split into the tribes Hominini and Gorillini. The early Hominini split further, separating the line to Homo from the lineage of Pan. Currently, tribe Hominini designates the subtribes Hominina, containing genus Homo; Panina, genus Pan; and Australopithecina, with several extinct genera—the subtribes are not labelled on this chart.

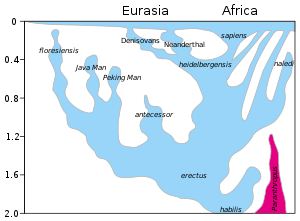

A model of the evolution of the genus Homo over the last 2 million years (vertical axis). The rapid "Out of Africa" expansion of H. sapiens is indicated at the top of the diagram, with admixture indicated with Neanderthals, Denisovans, and unspecified archaic African hominins. Late survival of robust australopithecines (Paranthropus) alongside Homo until 1.2 Mya is indicated in purple.

The Latin noun homō (genitive hominis) means "human being" or "man" in the generic sense of "human being, mankind". The binomial name Homo sapiens was coined by Carl Linnaeus (1758). Names for other species of the genus were introduced beginning in the second half of the 19th century (H. neanderthalensis 1864, H. erectus 1892).

Even today, the genus Homo has not been properly defined. Since the early human fossil record began to slowly emerge from the earth, the boundaries and definitions of the genus Homo have been poorly defined and constantly in flux. Because there was no reason to think it would ever have any additional members, Carl Linnaeus did not even bother to define Homo when he first created it for humans in the 18th century. The discovery of Neanderthal brought the first addition.

The genus Homo was given its taxonomic name to suggest that its member species can be classified as human. And, over the decades of the 20th century, fossil finds of pre-human and early human species from late Miocene and early Pliocene times produced a rich mix for debating classifications. There is continuing debate on delineating Homo from Australopithecus—or, indeed, delineating Homo from Pan, as one body of scientists argue that the two species of chimpanzee should be classed with genus Homo rather than Pan. Even so, classifying the fossils of Homo coincides with evidences of: 1) competent human bipedalism in Homo habilis inherited from the earlier Australopithecus of more than four million years ago, (see Laetoli); and 2) human tool culture having begun by 2.5 million years ago.

From the late-19th to mid-20th centuries, a number of new taxonomic names including new generic names were proposed for early human fossils; most have since been merged with Homo in recognition that Homo erectus was a single and singular species with a large geographic spread of early migrations. Many such names are now dubbed as "synonyms" with Homo, including Pithecanthropus, Protanthropus, Sinanthropus, Cyphanthropus, Africanthropus, Telanthropus, Atlanthropus, and Tchadanthropus.

Classifying the genus Homo into species and subspecies is subject to incomplete information and remains poorly done. This has led to using common names ("Neanderthal" and "Denisovan") in even scientific papers to avoid trinomial names or the ambiguity of classifying groups as incertae sedis (uncertain placement)—for example, H. neanderthalensis vs. H. sapiens neanderthalensis, or H. georgicus vs. H. erectus georgicus. Some recently extinct species in the genus Homo are only recently discovered and do not as yet have consensus binomial names (see Denisova hominin and Red Deer Cave people). Since the beginning of the Holocene, it is likely that Homo sapiens (anatomically modern humans) have been the only extant species of Homo.

John Edward Gray (1825) was an early advocate of classifying taxa by designating tribes and families. Wood and Richmond (2000) proposed that Hominini ("hominins") be designated as a tribe that comprised all species of early humans and pre-humans ancestral to humans back to after the chimpanzee-human last common ancestor; and that Hominina be designated a subtribe of Hominini to include only the genus Homo—that is, not including the earlier upright walking hominins of the Pliocene such as Australopithecus, Orrorin tugenensis, Ardipithecus, or Sahelanthropus. Designations alternative to Hominina existed, or were offered: Australopithecinae (Gregory & Hellman 1939) and Preanthropinae (Cela-Conde & Altaba 2002); and later, Cela-Conde and Ayala (2003) proposed that the four genera Australopithecus, Ardipithecus, Praeanthropus, and Sahelanthropus be grouped with Homo within Hominina.

Evolution

Australopithecus

Forensic reconstruction of A. afarensis

Several species, including Australopithecus garhi, Australopithecus sediba, Australopithecus africanus, and Australopithecus afarensis, have been proposed as the direct ancestor of the Homo lineage. These species have morphological features that align them with Homo, but there is no consensus as to which gave rise to Homo.

Especially since the 2010s, the delineation of Homo from Australopithecus has become more contentious. Traditionally, the advent of Homo has been taken to coincide with the first use of stone tools (the Oldowan industry), and thus by definition with the beginning of the Lower Palaeolithic. But in 2010, evidence was presented that seems to attribute the use of stone tools to Australopithecus afarensis around 3.3 million years ago, close to a million years before the first appearance of Homo. LD 350-1, a fossil mandible fragment dated to 2.8 Mya, discovered in 2015 in Afar, Ethiopia, was described as combining "primitive traits seen in early Australopithecus with derived morphology observed in later Homo. Some authors would push the development of Homo close to or even past 3 Mya. Others have voiced doubt as to whether Homo habilis should be included in Homo, proposing an origin of Homo with Homo erectus at roughly 1.9 Mya instead.

The most salient physiological development between the earlier australopithecine species and Homo is the increase in endocranial volume (ECV), from about 460 cm3 (28 cu in) in A. garhi to 660 cm3 (40 cu in) in H. habilis and further to 760 cm3 (46 cu in) in H. erectus, 1,250 cm3 (76 cu in) in H. heidelbergensis and up to 1,760 cm3 (107 cu in) in H. neanderthalensis. However, a steady rise in cranial capacity is observed already in Autralopithecina and does not terminate after the emergence of Homo, so that it does not serve as an objective criterion to define the emergence of the genus.

Homo habilis

Forensic reconstruction of Homo habilis, exhibit in LWL-Museum für Archäologie, Herne, Germany (2007 photograph).

Homo habilis emerged about 2.1 Mya. Already before 2010, there were suggestions that H. habilis should not be placed in genus Homo but rather in Australopithecus. The main reason to include H. habilis in Homo, its undisputed tool use, has become obsolete with the discovery of Australopithecus tool use at least a million years before H. habilis. Furthermore, H. habilis was long thought to be the ancestor of the more gracile Homo ergaster (Homo erectus). In 2007, it was discovered that H. habilis and H. erectus coexisted for a considerable time, suggesting that H. erectus is not immediately derived from H. habilis but instead from a common ancestor. With the publication of Dmanisi skull 5 in 2013, it has become less certain that Asian H. erectus is a descendant of African H. ergaster which was in turn derived from H. habilis. Instead, H. ergaster and H. erectus appear to be variants of the same species, which may have originated in either Africa or Asia and widely dispersed throughout Eurasia (including Europe, Indonesia, China) by 0.5 Mya.

Homo erectus

Homo erectus has often been assumed to have developed anagenetically from Homo habilis from about 2 million years ago. This scenario was strengthened with the discovery of Homo erectus georgicus, early specimens of H. erectus found in the Caucasus, which seemed to exhibit transitional traits with H. habilis. As the earliest evidence for H. erectus was found outside of Africa, it was considered plausible that H. erectus developed in Eurasia and then migrated back to Africa. Based on fossils from the Koobi Fora Formation, east of Lake Turkana in Kenya, Spoor et al. (2007) argued that H. habilis may have survived beyond the emergence of H. erectus, so that the evolution of H. erectus would not have been anagenetically, and H. erectus would have existed alongside H. habilis for about half a million years (1.9 to 1.4 million years ago), during the early Calabrian.A separate South African species Homo gautengensis has been postulated as contemporary with Homo erectus in 2010.

Dispersal

By about 1.8 million years ago, Homo erectus is present in both East Africa (Homo ergaster) and in Western Asia (Homo georgicus). The ancestors of Indonesian Homo floresiensis may have left Africa even earlier.Homo erectus and related or derived archaic human species over the next 1.5 million years spread throughout Africa and Eurasia. Europe is reached by about 0.5 Mya by Homo heidelbergensis.

Homo neanderthalensis and Homo sapiens develop after about 300 kya. Homo naledi is present in Southern Africa by 300 kya.

H. sapiens soon after its first emergence spread throughout Africa, and to Western Asia in several waves, possibly as early as 250 kya, and certainly by 130 kya. Most notable is the Southern Dispersal of H. sapiens around 60 kya, which led to the lasting peopling of Oceania and Eurasia by anatomically modern humans. H. sapiens interbred with archaic humans both in Africa and in Eurasia, in Eurasia notably with Neanderthals and Denisovans.

Among extant populations of Homo sapiens, the deepest temporal division is found in the San people of Southern Africa, estimated at close to 130,000 years, or possibly more than 300,000 years ago. Temporal division among non-Africans is of the order of 60,000 years in the case of Australo-Melanesians. Division of Europeans and East Asians is of the order of 50,000 years, with repeated and significant admixture events throughout Eurasia during the Holocene.

Archaic human species may have survived until the beginning of the Holocene (Red Deer Cave people), although they were mostly extinct or absorbed by the expanding H. sapiens populations by 40 kya.

List of species

The species status of H. rudolfensis, H. ergaster, H. georgicus, H. antecessor, H. cepranensis, H. rhodesiensis, H. neanderthalensis, Denisova hominin, Red Deer Cave people, and H. floresiensis remains under debate. H. heidelbergensis and H. neanderthalensis are closely related to each other and have been considered to be subspecies of H. sapiens.There has historically been a trend to postulate "new human species" based on as little as an individual fossil. A "minimalist" approach to human taxonomy recognizes at most three species, Homo habilis (2.1–1.5 Mya, membership in Homo questionable), Homo erectus (1.8–0.1 Mya, including the majority of the age of the genus, and the majority of archaic varieties as subspecies, including H. heidelbergensis as a late or transitional variety) and Homo sapiens (300 kya to present, including H. neanderthalensis and other varieties as subspecies).

![[2;1,2,1,1,4,1,1,6,1,1,8,1,\ldots \;].](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c259691dfec787fa250436b39b9a345df73ea01d)

![x=[u_{0};u_{1},u_{2},\ldots ]\,,](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e87792fa6c0f2592eb8c5dc98471a1541a5d7742)

![y=[v_{0};v_{1},v_{2},\ldots ]\,,](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/aecf023c0887d9c6973392b51ef41fe65bab1a66)