| Warren Court | |

|---|---|

| |

| October 5, 1953 – June 23, 1969 (15 years, 261 days) | |

| Seat | Supreme Court Building Washington, D.C. |

| No. of positions | 9 |

| Warren Court decisions | |

| |

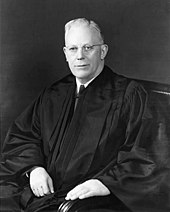

The Warren Court was the period in the history of the Supreme Court of the United States during which Earl Warren served as the chief justice. He replaced the deceased Fred M. Vinson as chief justice in 1953 and remained in office until retiring in 1969, at which point he was replaced by Warren E. Burger. The Warren Court is often considered the most liberal court in U.S. history.

The Warren Court expanded civil rights, civil liberties, judicial power, and the federal power in dramatic ways. It has been widely recognized that the court, led by the liberal bloc, created a major "Constitutional Revolution" in U.S. history.

The Warren Court brought "one man, one vote" to the United States through a series of rulings, and created the Miranda warning. In addition, the court was both applauded and criticized for bringing an end to de jure racial segregation in the United States, incorporating the Bill of Rights (i.e. including it in the 14th Amendment Due Process clause), and ending officially sanctioned voluntary prayer in public schools. The period is recognized as the most liberal point that judicial power had ever reached, but with a substantial continuing impact.

Membership

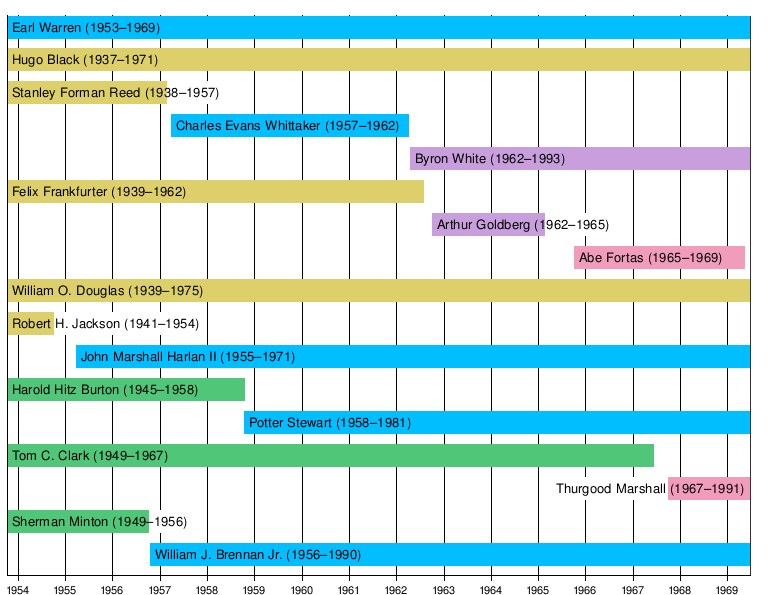

The Warren Court began on October 5, 1953, when President Dwight D. Eisenhower appointed Earl Warren, the incumbent governor of California, to replace Fred Vinson as Chief Justice of the United States. The court began with Warren and the final eight members of the Vinson Court: Hugo Black, Stanley Forman Reed, Felix Frankfurter, William O. Douglas, Robert H. Jackson, Harold Hitz Burton, Tom C. Clark, and Sherman Minton.

Jackson died in 1954 and Minton retired in 1956, and they were replaced by John Marshall Harlan II and William Brennan. Another vacancy took place when Reed retired in 1957 and was replaced by Charles Evans Whittaker, and then Burton retired in 1958, with Eisenhower appointing Potter Stewart in his place. When Frankfurter and Whittaker retired in 1962, then-President John F. Kennedy was given the power to appoint two new justices: Byron White and Arthur Goldberg. However, President Lyndon B. Johnson encouraged Goldberg to resign in 1965 to become Ambassador to the United Nations, and nominated Abe Fortas to take his place. Clark retired in 1967, and Johnson appointed the first African American justice, Thurgood Marshall to the court. The Warren Court concluded on June 23, 1969 when Earl Warren retired and was replaced by Warren E. Burger. Prominent members of the Court during the Warren Court era besides the Chief Justice included Associate Justices: Brennan, Douglas, Black, Frankfurter, and Harlan II.

Timeline

Other branches

Presidents during this court included Dwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, and Richard Nixon. Congresses during this court included 83rd through the 91st United States Congresses.

Warren's leadership

One of the primary factors in Warren's leadership was his political background, having served two and a half terms as Governor of California (1943–1953) and experience as the Republican candidate for vice president in 1948 (as running mate of Thomas E. Dewey). Warren brought a strong belief in the remedial power of law. According to historian Bernard Schwartz, Warren's view of the law was pragmatic, seeing it as an instrument for obtaining equity and fairness. Schwartz argues that Warren's approach was most effective "when the political institutions had defaulted on their responsibility to try to address problems such as segregation and reapportionment and cases where the constitutional rights of defendants were abused."

A related component of Warren's leadership was his focus on broad ethical principles, rather than narrower interpretative structures. Describing the latter as "conventional reasoning patterns," Professor G. Edward White suggests Warren often disregarded these in groundbreaking cases such as Brown v. Board of Education, Reynolds v. Sims and Miranda v. Arizona, where such traditional sources of precedent were stacked against him. White suggests Warren's principles "were philosophical, political, and intuitive, not legal in the conventional technical sense."

Warren's leadership was characterized by remarkable consensus on the court, particularly in some of the most controversial cases. These included Brown v. Board of Education, Gideon v. Wainwright, and Cooper v. Aaron, which were unanimously decided, as well as Abington School District v. Schempp and Engel v. Vitale, each striking down religious recitations in schools with only one dissent. In an unusual action, the decision in Cooper was personally signed by all nine justices, with the three new members of the Court adding that they supported and would have joined the Court's decision in Brown v. Board.

Fallon says that, "Some thrilled to the approach of the Warren Court. Many law professors were perplexed, often sympathetic to the Court's results but skeptical of the soundness of its constitutional reasoning. And some of course were horrified."

Vision

Professor John Hart Ely in his book Democracy and Distrust famously characterized the Warren Court as a "Carolene Products Court". This referred to the famous Footnote Four in United States v. Carolene Products, in which the Supreme Court had suggested that heightened judicial scrutiny might be appropriate in three types of cases:

- those where a law was challenged as a deprivation of a specifically enumerated right (such as a challenge to a law because it denies "freedom of speech", a phrase specifically included in the Bill of Rights);

- those where a challenged law made it more difficult to achieve change through normal political processes; and

- those where a law impinged on the rights of "discrete and insular minorities."

The Warren Court's doctrine can be seen as proceeding aggressively in these general areas:

- its aggressive reading of the first eight amendments in the Bill of Rights (as "incorporated" against the states by the Fourteenth Amendment)

- its commitment to unblocking the channels of political change ("one-man, one-vote")

- its vigorous protection of the rights of racial minority groups

The Warren Court, while in many cases taking a broad view of individual rights, generally declined to read the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment broadly, outside of the incorporation context (see Ferguson v. Skrupa, but see also Griswold v. Connecticut). The Warren Court's decisions were also strongly nationalist in thrust, as the Court read Congress's power under the Commerce Clause quite broadly and often expressed an unwillingness to allow constitutional rights to vary from state to state (as was explicitly manifested in Cooper v. Aaron).

Professor Rebecca Zietlow argues that the Warren Court brought an expansion in the "rights of belonging", which she characterizes as "rights that promote an inclusive vision of who belongs to the national community and facilitate equal membership in that community".

Archibald Cox, who as Solicitor General from 1961 to 1965 saw the Court up close, summarized: "The responsibility of government for equality among men, the openness of American society to change and reform, and the decency of the administration of criminal justice received both creative and enduring impetus from the work of the Warren Court."

Historically significant decisions

Important decisions during the Warren Court years included decisions holding segregation policies in public schools (Brown v. Board of Education) and anti-miscegenation laws unconstitutional (Loving v. Virginia); ruling that the Constitution protects a general right to privacy (Griswold v. Connecticut); that states are bound by the decisions of the Supreme Court and cannot ignore them (Cooper v. Aaron); that public schools cannot have official prayer (Engel v. Vitale) or mandatory Bible readings (Abington School District v. Schempp); the scope of the doctrine of incorporation (Mapp v. Ohio, Miranda v. Arizona) was dramatically increased; reading an equal protection clause into the Fifth Amendment (Bolling v. Sharpe); holding that the states may not apportion a chamber of their legislatures in the manner in which the United States Senate is apportioned (Reynolds v. Sims); and holding that the Constitution requires active compliance (Gideon v. Wainwright).

- Racial segregation: Brown v. Board of Education, Bolling v. Sharpe, Cooper v. Aaron, Gomillion v. Lightfoot, Griffin v. County School Board, Green v. School Board of New Kent County, Lucy v. Adams, Loving v. Virginia, Boynton v. Virginia

- Voting, redistricting, and malapportionment: Baker v. Carr, Reynolds v. Sims, Wesberry v. Sanders

- Criminal procedure: Brady v. Maryland, Mapp v. Ohio, Miranda v. Arizona, Escobedo v. Illinois, Gideon v. Wainwright, Katz v. United States, Terry v. Ohio

- Free speech: New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, Brandenburg v. Ohio, Yates v. United States, Roth v. United States, Jacobellis v. Ohio, Memoirs v. Massachusetts, Tinker v. Des Moines School District

- Establishment Clause: Engel v. Vitale, Abington School District v. Schempp

- Free Exercise Clause: Sherbert v. Verner

- Right to privacy and reproductive rights: Griswold v. Connecticut

- Cruel and unusual punishment: Trop v. Dulles, Robinson v. California

Warren's role

Warren took his seat January 11, 1954, on a recess appointment by President Eisenhower; the Senate confirmed him six weeks later. Despite his lack of judicial experience, his years in the Alameda County district attorney's office and as state attorney general gave him far more knowledge of the law in practice than most other members of the Court had. Warren's greatest asset, what made him in the eyes of many of his admirers "Super Chief," was his political skill in manipulating the other justices. Over the years his ability to lead the Court, to forge majorities in support of major decisions, and to inspire liberal forces around the nation, outweighed his intellectual weaknesses. Warren realized his weakness and asked the senior associate justice, Hugo L. Black, to preside over conferences until he became accustomed to the drill. A quick study, Warren soon was in fact, as well as in name, the Court's chief justice.

When Warren joined the Court in 1954 all the justices had been appointed by Franklin D. Roosevelt or Truman, and all were committed New Deal liberals. They disagreed about the role that the courts should play in achieving liberal goals. The Court was split between two warring factions. Felix Frankfurter and Robert H. Jackson led one faction, which insisted upon judicial self-restraint and insisted courts should defer to the policymaking prerogatives of the White House and Congress. Hugo Black and William O. Douglas led the opposing faction that agreed the court should defer to Congress in matters of economic policy, but felt the judicial agenda had been transformed from questions of property rights to those of individual liberties, and in this area courts should play a more central role. Warren's belief that the judiciary must seek to do justice, placed him with the latter group, although he did not have a solid majority until after Frankfurter's retirement in 1962.

Decisions

Warren was a more liberal justice than anyone had anticipated. Warren was able to craft a long series of landmark decisions because he built a winning coalition. When Frankfurter retired in 1962 and President John F. Kennedy named labor union lawyer Arthur Goldberg to replace him, Warren finally had the fifth vote for his liberal majority. William J. Brennan, Jr., a liberal Democrat appointed by Eisenhower in 1956, was the intellectual leader of the faction that included Black and Douglas. Brennan complemented Warren's political skills with the strong legal skills Warren lacked. Warren and Brennan met before the regular conferences to plan out their strategy.

Brown v. Board of Education (1954)

Brown v. Board of Education 347 U.S. 483 (1954) banned the segregation of public schools. The very first case put Warren's leadership skills to an extraordinary test. The Legal Defense Fund of the NAACP (a small legal group formed for tax reasons from the much better known NAACP) had been waging a systematic legal fight against the "separate but equal" doctrine enunciated in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) and finally had challenged Plessy in a series of five related cases, which had been argued before the Court in the spring of 1953. However the justices had been unable to decide the issue and asked to rehear the case in fall 1953, with special attention to whether the Fourteenth Amendment's Equal Protection Clause prohibited the operation of separate public schools for whites and blacks.

While all but one justice personally rejected segregation, the self-restraint faction questioned whether the Constitution gave the Court the power to order its end. Warren's faction believed the Fourteenth Amendment did give the necessary authority and were pushing to go ahead. Warren, who held only a recess appointment, held his tongue until the Senate, dominated by southerners, confirmed his appointment. Warren told his colleagues after oral argument that he believed segregation violated the Constitution and that only if one considered African Americans inferior to whites could the practice be upheld. But he did not push for a vote. Instead, he talked with the justices and encouraged them to talk with each other as he sought a common ground on which all could stand. Finally he had eight votes, and the last holdout, Stanley Reed of Kentucky, agreed to join the rest. Warren drafted the basic opinion in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) and kept circulating and revising it until he had an opinion endorsed by all the members of the Court.

The unanimity Warren achieved helped speed the drive to desegregate public schools, which came about under President Richard M. Nixon. Throughout his tenure in the bench, Warren succeeded in keeping all decisions concerning segregation unanimous. Brown applied to schools, but soon the Court enlarged the concept to other state actions, striking down racial classification in many areas. Congress ratified the process in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Warren did compromise by agreeing to Frankfurter's demand that the Court go slowly in implementing desegregation; Warren used Frankfurter's suggestion that a 1955 decision (Brown II) include the phrase "all deliberate speed."

The Brown decision of 1954 marked, in dramatic fashion, the radical shift in the Court's – and the nation's – priorities from issues of property rights to civil liberties. Under Warren the courts became an active partner in governing the nation, although still not coequal. Warren never saw the courts as a backward-looking branch of government.

The Brown decision was a powerful moral statement. His biographer concludes, "If Warren had not been on the Court, the Brown decision might not have been unanimous and might not have generated a moral groundswell that was to contribute to the emergence of the civil rights movement of the 1960s. Warren was never a legal scholar on par with Frankfurter or a great advocate of particular doctrines, as were Black and Douglas. Instead, he believed that in all branches of government common sense, decency, and elemental justice were decisive, not stare decisis (that is, reliance on previous Court decisions), tradition, or the text of the Constitution. He wanted results that in his opinion reflected the best American sentiments. He felt racial segregation was simply wrong, and Brown, whatever its doctrinal defects, remains a landmark decision primarily because of Warren's interpretation of the equal protection clause.

Reapportionment

The one man, one vote cases (Baker v. Carr and Reynolds v. Sims) of 1962–1964, had the effect of ending the over-representation of rural areas in state legislatures, as well as the under-representation of suburbs. Central cities – which had long been underepresented – were now losing population to the suburbs and were not greatly affected.

Warren's priority on fairness shaped other major decisions. In 1962, over the strong objections of Frankfurter, the Court agreed that questions regarding malapportionment in state legislatures were not political issues, and thus were not outside the Court's purview. For years underpopulated rural areas had deprived metropolitan centers of equal representation in state legislatures. In Warren's California, Los Angeles County had only one state senator. Cities had long since passed their peak, and now it was the middle class suburbs that were underrepresented. Frankfurter insisted that the Court should avoid this "political thicket" and warned that the Court would never be able to find a clear formula to guide lower courts in the rash of lawsuits sure to follow. But Douglas found such a formula: "one man, one vote."

In the key apportionment case Reynolds v. Sims (1964) Warren delivered a civics lesson: "To the extent that a citizen's right to vote is debased, he is that much less a citizen," Warren declared. "The weight of a citizen's vote cannot be made to depend on where he lives. This is the clear and strong command of our Constitution's Equal Protection Clause." Unlike the desegregation cases, in this instance, the Court ordered immediate action, and despite loud outcries from rural legislators, Congress failed to reach the two-thirds needed pass a constitutional amendment. The states complied, reapportioned their legislatures quickly and with minimal troubles. Numerous commentators have concluded reapportionment was the Warren Court's great "success" story.

Due process and rights of defendants (1963–1966)

In Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963) the Court held that the Sixth Amendment required that all indigent criminal defendants receive publicly funded counsel (Florida law at that time required the assignment of free counsel to indigent defendants only in capital cases); Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966) required that certain rights of a person interrogated while in police custody be clearly explained, including the right to an attorney (often called the "Miranda warning").

While most Americans eventually agreed that the Court's desegregation and apportionment decisions were fair and right, disagreement about the "due process revolution" continues into the 21st century. Warren took the lead in criminal justice; despite his years as a tough prosecutor, he always insisted that the police must play fair or the accused should go free. Warren was privately outraged at what he considered police abuses that ranged from warrantless searches to forced confessions.

Warren’s Court ordered lawyers for indigent defendants, in Gideon v. Wainwright (1963), and prevented prosecutors from using evidence seized in illegal searches, in Mapp v. Ohio (1961). The famous case of Miranda v. Arizona (1966) summed up Warren's philosophy. Everyone, even one accused of crimes, still enjoyed constitutionally protected rights, and the police had to respect those rights and issue a specific warning when making an arrest. Warren did not believe in coddling criminals; thus in Terry v. Ohio (1968) he gave police officers leeway to stop and frisk those they had reason to believe held weapons.

Conservatives angrily denounced the "handcuffing of the police." Violent crime and homicide rates shot up nationwide in the following years; in New York City, for example, after steady to declining trends until the early 1960s, the homicide rate doubled in the period from 1964 to 1974 from just under 5 per 100,000 at the beginning of that period to just under 10 per 100,000 in 1974. Controversy exists about the cause, with conservatives blaming the Court decisions, and liberals pointing to the demographic boom and increased urbanization and income inequality characteristic of that era. After 1992 the homicide rates fell sharply.

First Amendment

The Warren Court also sought to expand the scope of application of the First Amendment. The Court's decision outlawing mandatory school prayer in Engel v. Vitale (1962) brought vehement complaints by conservatives that echoed into the 21st century.

Other Issues

Warren worked to nationalize the Bill of Rights by applying it to the states. Moreover, in one of the landmark cases decided by the Court, Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), the Warren Court affirmed a constitutionally protected right of privacy, emanating from the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, also known as substantive due process.

This ruling was critical even after Warren's retirement (and Fortas' untimely departure as well) for the outcome of the Roe v. Wade case which recognized the constitutional right to abortion.

With the exception of the desegregation decisions, few decisions were unanimous. The eminent scholar Justice John Marshall Harlan II took Frankfurter's place as the Court's self-constraint spokesman, often joined by Potter Stewart and Byron R. White. But with the appointment of Thurgood Marshall, the first black justice (as well as the first non-white justice), and Abe Fortas (replacing Goldberg), Warren could count on six votes in most cases.