Ayurveda (/ˌɑːjʊərˈveɪdə, -ˈviː-/) is an alternative medicine system with historical roots in the Indian subcontinent. The theory and practice of Ayurveda is pseudoscientific. The Indian Medical Association (IMA) characterises the practice of modern medicine by Ayurvedic practitioners as quackery.

The main classical Ayurveda texts begin with accounts of the transmission of medical knowledge from the gods to sages, and then to human physicians. In Sushruta Samhita (Sushruta's Compendium), Sushruta wrote that Dhanvantari, Hindu god of Ayurveda, incarnated himself as a king of Varanasi and taught medicine to a group of physicians, including Sushruta. Ayurveda therapies have varied and evolved over more than two millennia. Therapies are typically based on complex herbal compounds, minerals and metal substances (perhaps under the influence of early Indian alchemy or rasa shastra). Ancient Ayurveda texts also taught surgical techniques, including rhinoplasty, kidney stone extractions, sutures, and the extraction of foreign objects. Ayurveda has been adapted for Western consumption, notably by Baba Hari Dass in the 1970s and Maharishi Ayurveda in the 1980s.

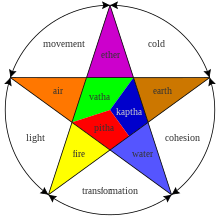

Some scholars assert that Ayurveda originated in prehistoric times, and that some of the concepts of Ayurveda have existed from the time of the Indus Valley Civilization or even earlier. Ayurveda developed significantly during the Vedic period and later some of the non-Vedic systems such as Buddhism and Jainism also developed medical concepts and practices that appear in the classical Ayurveda texts. Doṣa balance is emphasized, and suppressing natural urges is considered unhealthy and claimed to lead to illness. Ayurveda treatises describe three elemental doṣas viz. vāta, pitta and kapha, and state that balance (Skt. sāmyatva) of the doṣas results in health, while imbalance (viṣamatva) results in disease. Ayurveda treatises divide medicine into eight canonical components. Ayurveda practitioners had developed various medicinal preparations and surgical procedures from at least the beginning of the common era.

There is no good evidence that Ayurveda is effective for treating any disease. Ayurvedic preparations have been found to contain lead, mercury, and arsenic, substances known to be harmful to humans. In a 2008 study, close to 21% of U.S. and Indian-manufactured patent Ayurvedic medicines sold through the Internet were found to contain toxic levels of heavy metals, specifically lead, mercury, and arsenic. The public health implications of such metallic contaminants in India are unknown.

Eight components

The earliest classical Sanskrit works on Ayurveda describe medicine as being divided into eight components (Skt. aṅga). This characterization of the physicians' art, "the medicine that has eight components" (Skt. cikitsāyām aṣṭāṅgāyāṃ चिकित्सायामष्टाङ्गायाम्), is first found in the Sanskrit epic the Mahābhārata, c. 4th century BCE. The components are:

- Kāyachikitsā: general medicine, medicine of the body

- Kaumāra-bhṛtya (Pediatrics): Discussions about prenatal and postnatal care of baby and mother, methods of conception; choosing the child's gender, intelligence, and constitution; and childhood diseases and midwifery.

- Śalyatantra: surgical techniques and the extraction of foreign objects

- Śhālākyatantra: treatment of ailments affecting ears, eyes, nose, mouth, etc. ("ENT")

- Bhūtavidyā: pacification of possessing spirits, and the people whose minds are affected by such possession

- Agadatantra/Vishagara-vairodh Tantra (Toxicology): It includes subjects about epidemics, toxins in animals, vegetables and minerals. It as well contain keys for recognizing those anomalies and their antidotes.

- Rasāyantantra: rejuvenation and tonics for increasing lifespan, intellect and strength

- Vājīkaraṇatantra: aphrodisiacs and treatments for increasing the volume and viability of semen and sexual pleasure. It also deals with infertility problems (for those hoping to conceive) and spiritual development (transmutation of sexual energy into spiritual energy).

Principles and terminology

The word "ayurveda" is Sanskrit: आयुर्वेद, Āyurveda, meaning knowledge of life and longevity.

The central theoretical ideas of Ayurveda developed in the mid-first millennium BCE, and show parallels with Sāṅkhya and Vaiśeṣika philosophies, as well as with Buddhism and Jainism. Balance is emphasized, and suppressing natural urges is considered unhealthy and claimed to lead to illness. For example, to suppress sneezing is said to potentially give rise to shoulder pain. However, people are also cautioned to stay within the limits of reasonable balance and measure when following nature's urges. For example, emphasis is placed on moderation of food intake, sleep, and sexual intercourse.

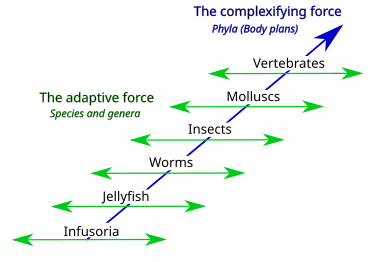

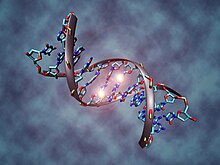

According to ayurveda, the human body is composed of tissues (dhatus), waste (malas), and biomaterials (doshas). The seven dhatus are plasma (rasa), blood (rakta), muscles (māmsa), fat (meda), bone (asthi), marrow (majja), and semen (shukra). Like the medicine of classical antiquity, Ayurveda has historically divided bodily substances into five classical elements, (Sanskrit) panchamahabhuta, viz. earth, water, fire, air and ether. There are also twenty gunas (qualities or characteristics) which are considered to be inherent in all matter. These are organized in ten pairs: heavy/light, cold/hot, unctuous/dry, dull/sharp, stable/mobile, soft/hard, non-slimy/slimy, smooth/coarse, minute/gross, and viscous/liquid.

The three elemental bodily humors, the doshas or tridosha, are vata (space or air, equated with the nervous system), pitta (fire, equated with enzymes), and kapha (earth and water, equated with mucus). A parallel set of mental doshas termed satogun, rajogun, and tamogun control psychology. Each dosha has particular attributes and roles within the body and mind; the natural predominance of one or more doshas thus explains a person's physical constitution (prakriti) and personality. Ayurvedic tradition holds that imbalance among the bodily and mental doshas is a major etiologic component of disease. One Ayurvedic view is that the doshas are balanced when they are equal to each other, while another view is that each human possesses a unique combination of the doshas which define this person's temperament and characteristics. In either case, it says that each person should modulate their behavior or environment to increase or decrease the doshas and maintain their natural state. Practitioners of Ayurveda must determine an individual's bodily and mental dosha makeup, as certain prakriti are said to predispose one to particular diseases. For example, a person who is thin, shy, excitable, has a pronounced Adam's apple, and enjoys of esoteric knowledge is likely vata prakriti and therefore more susceptible to conditions such as flatulence, stuttering, and rheumatism. Deranged vata is also associated with certain mental disorders due to excited or excess vayu (gas), although the Ayurvedic text Charaka Samhita also attributes "insanity" (unmada) to cold food and possession by the ghost of a sinful Brahman (brahmarakshasa).

Ama (a Sanskrit word meaning "uncooked" or "undigested" ) is used to refer to the concept of anything that exists in a state of incomplete transformation. With regards to oral hygiene, it is claimed to be a toxic byproduct generated by improper or incomplete digestion. The concept has no equivalent in standard medicine.

In medieval taxonomies of the Sanskrit knowledge systems, Ayurveda is assigned a place as a subsidiary Veda (upaveda). Some medicinal plant names from the Atharvaveda and other Vedas can be found in subsequent Ayurveda literature. The earliest recorded theoretical statements about the canonical models of disease in Ayurveda occur in the earliest Buddhist Canon.

Practice

Ayurvedic practitioners regard physical existence, mental existence, and personality as their own unique units, with each element being able to influence the others. This is a holistic approach used during diagnosis and therapy, and is a fundamental aspect of Ayurveda. Another part of Ayurvedic treatment says that there are channels (srotas) which transport fluids, and that the channels can be opened up by massage treatment using oils and Swedana (fomentation). Unhealthy, or blocked, channels are thought to cause disease.

Diagnosis

Ayurveda has eight ways to diagnose illness, called Nadi (pulse), Mootra (urine), Mala (stool), Jihva (tongue), Shabda (speech), Sparsha (touch), Druk (vision), and Aakruti (appearance). Ayurvedic practitioners approach diagnosis by using the five senses. For example, hearing is used to observe the condition of breathing and speech. The study of the lethal points or marman marma is of special importance.

Treatment and prevention

Two of the eight branches of classical Ayurveda deal with surgery (Śalya-cikitsā and Śālākya-tantra), but contemporary Ayurveda tends to stress attaining vitality by building a healthy metabolic system and maintaining good digestion and excretion. Ayurveda also focuses on exercise, yoga, and meditation. One type of prescription is a Sattvic diet.

Ayurveda follows the concept of Dinacharya, which says that natural cycles (waking, sleeping, working, meditation etc.) are important for health. Hygiene, including regular bathing, cleaning of teeth, oil pulling, tongue scraping, skin care, and eye washing, is also a central practice.

Substances used

Plant-based treatments in Ayurveda may be derived from roots, leaves, fruits, bark, or seeds such as cardamom and cinnamon. In the 19th century, William Dymock and co-authors summarized hundreds of plant-derived medicines along with the uses, microscopic structure, chemical composition, toxicology, prevalent myths and stories, and relation to commerce in British India. Animal products used in Ayurveda include milk, bones, and gallstones. In addition, fats are prescribed both for consumption and for external use. Consumption of minerals, including sulphur, arsenic, lead, copper sulfate and gold, are also prescribed. The addition of minerals to herbal medicine is called rasa shastra.

Ayurveda uses alcoholic beverages called Madya, which are said to adjust the doshas by increasing Pitta and reducing Vatta and Kapha. Madya are classified by the raw material and fermentation process, and the categories include: sugar-based, fruit-based, cereal-based, cereal-based with herbs, fermentated with vinegar, and tonic wines. The intended outcomes can include causing purgation, improving digestion or taste, creating dryness, or loosening joints. Ayurvedic texts describe Madya as non-viscid and fast-acting, and say that it enters and cleans minute pores in the body.

Purified opium is used in eight Ayurvedic preparations and is said to balance the Vata and Kapha doshas and increase the Pitta dosha. It is prescribed for diarrhea and dysentery, for increasing the sexual and muscular ability, and for affecting the brain. The sedative and pain-relieving properties of opium are considered in Ayurveda. The use of opium is found in the ancient Ayurvedic texts, and is first mentioned in the Sarngadhara Samhita (1300-1400 CE), a book on pharmacy used in Rajasthan in Western India, as an ingredient of an aphrodisiac to delay male ejaculation. It is possible that opium was brought to India along with or before Muslim conquests. The book Yoga Ratnakara (1700-1800 CE, unknown author), which is popular in Maharashtra, uses opium in a herbal-mineral composition prescribed for diarrhea. In the Bhaisajya Ratnavali, opium and camphor are used for acute gastroenteritis. In this drug, the respiratory depressant action of opium is counteracted by the respiratory stimulant property of Camphor. Later books have included the narcotic property for use as analgesic pain reliever.

Cannabis indica is also mentioned in the ancient Ayurveda books, and is first mentioned in the Sarngadhara Samhita as a treatment for diarrhea. In the Bhaisajya Ratnavali it is named as an ingredient in an aphrodisiac.

Ayurveda says that both oil and tar can be used to stop bleeding, and that traumatic bleeding can be stopped by four different methods: ligation of the blood vessel, cauterisation by heat, use of preparations to facilitate clotting, and use of preparations to constrict the blood vessels. Oils are also used in a number of ways, including regular consumption, anointing, smearing, head massage, application to affected areas, and oil pulling. Liquids may also be poured on the patient's forehead, a technique called shirodhara.

Panchakarma

According to Ayurveda, panchakarma are techniques to eliminate toxic elements from the body.

Current status

India

According to some sources, up to 80 percent of people in India use Ayurveda exclusively or combined with conventional Western medicine.

In 1970, the Indian Medical Central Council Act which aimed to standardise qualifications for Ayurveda practitioners and provide accredited institutions for its study and research was passed by the Parliament of India. In 1971, the Central Council of Indian Medicine (CCIM) was established under the Department of Ayurveda, Yoga and Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha medicine and Homoeopathy (AYUSH), Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, to monitor higher education in Ayurveda in India. The Indian government supports research and teaching in Ayurveda through many channels at both the national and state levels, and helps institutionalise traditional medicine so that it can be studied in major towns and cities. The state-sponsored Central Council for Research in Ayurvedic Sciences (CCRAS) is designed to do research on Ayurveda. Many clinics in urban and rural areas are run by professionals who qualify from these institutes. As of 2013, India has over 180 training centers offer degrees in traditional Ayurvedic medicine.

To fight biopiracy and unethical patents, in 2001 the government of India set up the Traditional Knowledge Digital Library as a repository for formulations of various systems of Indian medicine, such as Ayurveda, Unani and Siddha. The formulations come from over 100 traditional Ayurveda books. An Indian Academy of Sciences document quoting a 2003-04 report states that India had 432,625 registered medical practitioners, 13,925 dispensaries, 2,253 hospitals and a bed strength of 43,803. 209 under-graduate teaching institutions and 16 post-graduate institutions. Insurance companies cover expenses for Ayurvedic treatments in case of conditions such as spinal cord disorders, bone disorder, arthritis and cancer. Such claims constitute 5-10 percent of the country's health insurance claims.

Maharashtra Andhashraddha Nirmoolan Samiti, an organisation dedicated to fighting superstition in India, considers Ayurveda to be pseudoscience.

On 9 November 2014, India formed the Ministry of AYUSH. National Ayurveda Day is also observed in India on the birth of Dhanvantari that is Dhanteras.

Other countries on the Indian subcontinent

About 75%-80% of the population of Nepal use Ayurveda, and it is the most practiced form of medicine in the country.

The Sri Lankan tradition of Ayurveda is similar to the Indian tradition. Practitioners of Ayurveda in Sri Lanka refer to Sanskrit texts which are common to both countries. However, they do differ in some aspects, particularly in the herbs used.

In 1980, the Sri Lankan government established a Ministry of Indigenous Medicine to revive and regulate Ayurveda. The Institute of Indigenous Medicine (affiliated to the University of Colombo) offers undergraduate, postgraduate, and MD degrees in Ayurveda Medicine and Surgery, and similar degrees in unani medicine. In the public system, there are currently 62 Ayurvedic hospitals and 208 central dispensaries, which served about 3 million people (about 11% of Sri Lanka's population) in 2010. In total, there are about 20,000 registered practitioners of Ayurveda in the country.

According to the Mahavamsa, an ancient chronicle of Sinhalese royalty from the sixth century C.E., King Pandukabhaya of Sri Lanka (reigned 437 BCE to 367 BCE) had lying-in-homes and Ayurvedic hospitals (Sivikasotthi-Sala) built in various parts of the country. This is the earliest documented evidence available of institutions dedicated specifically to the care of the sick anywhere in the world. Mihintale Hospital is the oldest in the world.

Outside the Indian subcontinent

Ayurveda is a system of traditional medicine developed during antiquity and the medieval period, and as such is comparable to pre-modern Chinese and European systems of medicine. However, beginning in the 1960s, Ayurveda has been advertised as alternative medicine in the Western world. Due to different laws and medical regulations in the rest of the world, the unregulated practice and commercialisation of Ayurveda have raised ethical and legal issues. In some instances, Ayurvedic practices or terminology have also been adapted specifically for Western consumption, notably in the case of "Maharishi Ayurveda" in the 1980s. In some cases, this involved active fraud on the part of proponents of Ayurveda in an attempt to falsely represent the system as equal to the standards of modern medical research.

Baba Hari Dass was an early proponent who helped bring Ayurveda to the US in the early 1970s. He taught classes derived from the Suśrutha Saṃhitā and the Charaka Saṃhitha, leading to the establishment of the Mount Madonna Institute, College of Ayurveda, Ayurveda World, and Ayurvedic pharmacy. He invited several notable Ayurvedic teachers, including Vasant Lad, Sarita Shrestha, and Ram Harsh Singh. The Ayurvedic practitioner Michael Tierra wrote that "[t]he history of Ayurveda in North America will always owe a debt to the selfless contributions of Baba Hari Dass."

In the United States, the practice of Ayurveda is not licensed or regulated by any state. The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health says that "Few well-designed clinical trials and systematic research reviews suggest that Ayurvedic approaches are effective", warns against the issue of heavy metal poisoning, and emphasises the use of conventional health providers first.

Classification and efficacy

Although laboratory experiments suggest it is possible that some substances in Ayurveda might be developed into effective treatments, there is no evidence that any are effective in themselves. Cancer Research UK states that there is no evidence that ayurvedic medicine helps treat cancer in people, and some Ayurvedic drugs contain toxic substances or interact with legitimate cancer drugs in a harmful way.

Ayurvedic medicine is considered pseudoscientific because it confuses reality and metaphysical concepts, and because its premises are not based on science. Ethnologist Johannes Quack writes than although the rationalist movement Maharashtra Andhashraddha Nirmoolan Samiti officially labels Ayurveda – like astrology – a pseudoscience, these practices are in fact embraced by many of the movement's members.

A review of the use of Ayurveda for cardiovascular disease concluded that the evidence is not convincing for the use of any Ayurvedic herbal treatment for heart disease or hypertension, but that many herbs used by Ayurvedic practitioners could be appropriate for further research.

Research into ayurveda has been characterized as pseudoscience. Both the lack of scientific soundness in the theoretical foundations of ayurveda and the quality of research have been criticized.

Research

In India, research in Ayurveda is undertaken by the Ministry of AYUSH, an abbreviation for the Department of Ayurveda, Yoga and Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homoeopathy, through a national network of research institutes.

In Nepal, the National Ayurvedic Training and Research Centre (NATRC) researches medicinal herbs in the country.

In Sri Lanka, the Ministry of Health, Nutrition and Indigenous Medicine looks after the research in Ayurveda through various national research institutes.

Use of toxic metals

Rasa shastra, the practice of adding metals, minerals or gems to herbal preparations, may include toxic heavy metals such as lead, mercury and arsenic. The public health implications of metals in rasa shastra in India is unknown. Adverse reactions to herbs are described in traditional Ayurvedic texts, but practitioners are reluctant to admit that herbs could be toxic and that reliable information on herbal toxicity is not readily available. There is a communication gap between practitioners of modern medicine and Ayurveda.

Some traditional Indian herbal medicinal products contain harmful levels of heavy metals, including lead. For example, ghasard, a product commonly given to infants for digestive issues, has been found to have up to 1.6% lead concentration by weight, leading to lead encephalopathy. A 1990 study on Ayurvedic medicines in India found that 41% of the products tested contained arsenic, and that 64% contained lead and mercury. A 2004 study found toxic levels of heavy metals in 20% of Ayurvedic preparations made in South Asia and sold in the Boston area, and concluded that Ayurvedic products posed serious health risks and should be tested for heavy-metal contamination. A 2008 study of more than 230 products found that approximately 20% of remedies (and 40% of rasa shastra medicines) purchased over the Internet from U.S. and Indian suppliers contained lead, mercury or arsenic. A 2015 study of users in the United States found elevated blood lead levels in 40% of those tested, leading physician and former U.S. Air Force flight surgeon Harriet Hall to say that "Ayurveda is basically superstition mixed with a soupçon of practical health advice. And it can be dangerous."

Heavy metals are thought of as active ingredients by advocates of Indian herbal medicinal products. According to ancient Ayurvedic texts, certain physico-chemical purification processes such as samskaras or shodhanas (for metals) 'detoxify' the heavy metals in it. These are similar to the Chinese pao zhi, although the Ayurvedic techniques are more complex and may involve physical pharmacy techniques as well as mantras. However, these products have nonetheless caused severe lead poisoning and other toxic effects. Between 1978 and 2008, "more than 80 cases of lead poisoning associated with Ayurvedic medicine use [were] reported worldwide". In 2012, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) linked Ayurvedic drugs to lead poisoning, based on cases where toxic materials were found in the blood of pregnant women who had taken Ayurvedic drugs.

Ayurvedic practitioners argue that the toxicity of bhasmas (ash products) comes from improper manufacturing processes, contaminants, improper use of Ayurvedic medicine, quality of raw materials and that the end products and improper procedures are used by charlatans.

In India, the government ruled that Ayurvedic products must be labelled with their metallic content. However, in Current Science, a publication of the Indian Academy of Sciences, M. S. Valiathan said that "the absence of post-market surveillance and the paucity of test laboratory facilities [in India] make the quality control of Ayurvedic medicines exceedingly difficult at this time". In the United States, most Ayurvedic products are marketed without having been reviewed or approved by the FDA. Since 2007, the FDA has placed an import alert on some Ayurvedic products in order to prevent them from entering the United States. A 2012 toxicological review of mercury-based traditional herbo-metallic preparations concluded that the long-term pharmacotherapeutic and in-depth toxicity studies of these preparations are lacking.

History

According to modern Ayurvedic sources, the origins of Ayurveda have been traced to around 6,000 BCE when they originated as an oral tradition. Some of the concepts of Ayurveda have existed since the times of Indus Valley Civilization. The first recorded forms of Ayurveda as medical texts evolved from the Vedas. Ayurveda is a discipline of the upaveda or "auxiliary knowledge" in Vedic tradition. The origins of Ayurveda are also found in Atharvaveda, which contains 114 hymns and incantations described as magical cures for disease. There are various legendary accounts of the origin of Ayurveda, e.g. that it was received by Dhanvantari (or Divodasa) from Brahma. Tradition also holds that the writings of Ayurveda were influenced by a lost text by the sage Agnivesa.

Ayurveda is one of the few systems of medicine developed in ancient times that is still widely practiced in modern times. As such, it is open to the criticism that its conceptual basis is obsolete and that its contemporary practitioners have not taken account of the developments of modern medicine. Responses to this situation led to an impassioned debate in India during the early decades of the twentieth century, between proponents of unchanging tradition (śuddha "pure" ayurveda) and those who thought ayurveda should modernise and syncretize (aśuddha "impure, tainted" ayurveda). The political debate about the place of ayurveda in contemporary India has continued to the present (2015), both in the public arena and in government. Debate about the place of Ayurvedic medicine in the contemporary internationalized world also continues today (2015).

Main texts

There are three principal early texts on Ayurveda, the Charaka Samhita, the Sushruta Samhita and the Bhela Samhita. The dating of these works is historically complicated since they each internally present themselves as composite works compiled by several editors. All past scholarship on their dating has been evaluated by Meulenbeld in volumes IA and IB of his History of Indian Medical Literature. After considering the evidence and arguments concerning the Suśrutasaṃhitā, Meulenbeld states (IA, 348), "The Suśrutasaṃhitā is most probably the work of an unknown author who drew much of the material he incorporated in his treatise from a multiplicity of earlier sources from various periods. This may explain that many scholars yield to the temptation to recognize a number of distinct layers and, consequently, try to identify elements belonging to them. As we have seen, the identification of features thought to belong to a particular stratum is in many cases determined by preconceived ideas on the age of the strata and their supposed authors." The dating of this work to 600 BC was first proposed by Hoernle over a century ago, but has long since been overturned by subsequent historical research. The current consensus amongst medical historians of South Asia is that the Suśrutasaṃhitā was compiled over a period of time starting with a kernel of medical ideas from the century or two BCE and then being revised by several hands into its present form by about 500 CE. The view that the text was updated by the Buddhist scholar Nagarjuna in the 2nd century CE has been disproved, although the last chapter of the work, the Uttaratantra, was added by an unknown later author before 500 CE.

Similar arguments apply to the Charaka Samhita, written by Charaka, and the Bhela Samhita, attributed to Atreya Punarvasu, that are also dated to the 6th century BCE by non-specialist scholars but are in fact, in their present form, datable to a period between the second and fifth centuries CE. The Charaka Samhita was also updated by Dridhabala during the early centuries of the Common Era.

The Bower Manuscript (dated to the Gupta era, between the 4th and the 6th century CE) includes of excerpts from the Bheda Samhita and its description of concepts in Central Asian Buddhism. In 1987, A. F. R. Hoernle identified the scribe of the medical portions of the manuscript to be a native of India using a northern variant of the Gupta script, who had migrated and become a Buddhist monk in a monastery in Kucha. The Chinese pilgrim Fa Hsien (c. 337–422 AD) wrote about the healthcare system of the Gupta empire (320–550) and described the institutional approach of Indian medicine. This is also visible in the works of Charaka, who describes hospitals and how they should be equipped.

Other early texts are the Agnivesha Samhita, Kasyapa Samhita and Harita Samhita. The original edition of the Agnivesha Samhita, by Agnivesa, is dated to 1500 BCE, and it was later modified by Charaka. Kasyapa Samhita includes the treatise of Jivaka Kumar Bhaccha and is dated to the 6th century BCE. While Harita Samhita is dated to an earlier period, it is attributed to Harita, who was a disciple of Punarvasu Atreya. Some later texts are Astanga nighantu (8th Century) by Vagbhata, Paryaya ratnamala (9th century) by Madhava, Siddhasara nighantu (9th century) by Ravi Gupta, Dravyavali (10th Century), and Dravyaguna sangraha (11th century) by Chakrapani Datta, among others.

Illnesses portrayed

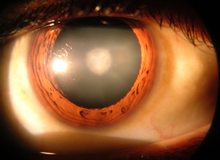

Underwood and Rhodes state that the early forms of traditional Indian medicine identified fever, cough, consumption, diarrhea, dropsy, abscesses, seizures, tumours, and leprosy, and that treatments included plastic surgery, lithotomy, tonsillectomy, couching (a form of cataract surgery), puncturing to release fluids in the abdomen, extraction of foreign bodies, treatment of anal fistulas, treating fractures, amputations, cesarean sections, and stitching of wounds. The use of herbs and surgical instruments became widespread. During this period, treatments were also prescribed for complex ailments, including angina pectoris, diabetes, hypertension, and stones.

Further development and spread

Ayurveda flourished throughout the Indian Middle Ages. Dalhana (fl. 1200), Sarngadhara (fl. 1300) and Bhavamisra (fl. 1500) compiled works on Indian medicine. The medical works of both Sushruta and Charaka were also translated into the Chinese language in the 5th century, and during the 8th century, they were translated into the Arabic and Persian language. The 9th-century Persian physician Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi was familiar with the text. The Arabic works derived from the Ayurvedic texts eventually also reached Europe by the 12th century. In Renaissance Italy, the Branca family of Sicily and Gaspare Tagliacozzi (Bologna) were influenced by the Arabic reception of the Sushruta's surgical techniques.

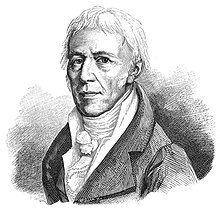

British physicians traveled to India to observe rhinoplasty being performed using Indian methods, and reports on their rhinoplasty methods were published in the Gentleman's Magazine in 1794. Instruments described in the Sushruta Samhita were further modified in Europe. Joseph Constantine Carpue studied plastic surgery methods in India for 20 years and, in 1815, was able to perform the first major rhinoplasty surgery in the western world, using the "Indian" method of nose reconstruction. In 1840 Brett published an article about this technique.

During the period of British colonial rule in India, the practice of Ayurveda was not adopted by the British Indian Government, which was in favor of modern medicine. After Indian independence, there was more focus on Ayurveda and other traditional medical systems. Ayurveda became a part of the Indian National health care system, with state hospitals for Ayurveda established across the country. However, the treatments of traditional medicines were not always integrated with others.