From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

|

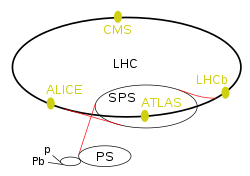

| LHC experiments | |

|---|---|

| ATLAS | A Toroidal LHC Apparatus |

| CMS | Compact Muon Solenoid |

| LHCb | LHC-beauty |

| ALICE | A Large Ion Collider Experiment |

| TOTEM | Total Cross Section, Elastic Scattering and Diffraction Dissociation |

| LHCf | LHC-forward |

| MoEDAL | Monopole and Exotics Detector At the LHC |

| LHC preaccelerators | |

| p and Pb | Linear accelerators for protons (Linac 2) and Lead (Linac 3) |

| (not marked) | Proton Synchrotron Booster |

| PS | Proton Synchrotron |

| SPS | Super Proton Synchrotron |

| Intersecting Storage Rings | CERN, 1971–1984 |

|---|---|

| Super Proton Synchrotron | CERN, 1981–1984 |

| ISABELLE | BNL, cancelled in 1983 |

| Tevatron | Fermilab, 1987–2011 |

| Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider | BNL, 2000–present |

| Superconducting Super Collider | Cancelled in 1993 |

| Large Hadron Collider | CERN, 2009–present |

| Very Large Hadron Collider | Theoretical |

The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) is the world's largest and most powerful particle collider, and the largest single machine in the world,[1] built by the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) from 1998 to 2008.

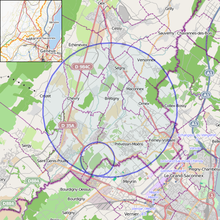

The LHC was built in collaboration with over 10,000 scientists and engineers from over 100 countries, as well as hundreds of universities and laboratories.[2] It lies in a tunnel 27 kilometres (17 mi) in circumference, as deep as 175 metres (574 ft) beneath the Franco-Swiss border near Geneva, Switzerland. It is also the longest machine ever built.

Its aim is to allow physicists to test the predictions of different theories of particle physics and high-energy physics like the Standard Model, and particularly prove or disprove the existence of the theorized Higgs boson[3] and of the large family of new particles predicted by supersymmetric theories.[4] The discovery of a particle matching the Higgs boson was confirmed by data from the LHC in 2013. The LHC is expected to address some of the unsolved questions of physics, advancing human understanding of physical laws. It contains seven detectors, each designed for certain kinds of research.

As of 2015, the LHC remains the largest and most complex experimental facility ever built. Its synchrotron is designed to collide two opposing particle beams of either protons at up to 4 teraelectronvolts (4 TeV or 0.64 microjoules), or lead nuclei (574 TeV per nucleus, or 2.76 TeV per nucleon),[5][6] with energies to be increased to around 6.5 TeV (13 TeV collision energy) —about seven times the previous record— in 2015. Collision data was also anticipated to be produced at an unprecedented rate of tens of petabytes per year, to be analysed by a grid-based computer network infrastructure connecting 140 computing centers in 35 countries[7][8] (by 2012 the LHC Computing Grid was the world's largest computing grid, comprising over 170 computing facilities in a worldwide network across 36 countries[9][10][11]).

The LHC went live on 10 September 2008, with proton beams successfully circulated in the main ring of the LHC for the first time,[12] but nine days later a faulty electrical connection led to the rupture of a liquid helium enclosure, causing both a magnet quench and several tons of helium gas escaping with explosive force. The incident resulted in damage to over 50 superconducting magnets and their mountings, and contamination of the vacuum pipe, and delayed further operations by 14 months.[13][14] On November 20, 2009 proton beams were successfully circulated again,[15][16] with the first recorded proton–proton collisions occurring three days later at the injection energy of 450 GeV per beam.[17] On March 30, 2010, the first collisions took place between two 3.5 TeV beams, setting a world record for the highest-energy man-made particle collisions,[18] and the LHC began its planned research program.

The LHC has discovered a massive 125 GeV boson (which subsequent results confirmed to be the long-sought Higgs boson) and several composite particles (hadrons) like the χb (3P) bottomonium state, created a quark–gluon plasma, and recorded the first observations of the very rare decay of the Bs meson into two muons (Bs0 → μ+μ−), which challenged the validity of existing models of supersymmetry.[19]

The LHC operated at 3.5 TeV per beam in 2010 and 2011 and at 4 TeV in 2012.[20] Proton–proton collisions are the main operation mode. It collided protons with lead nuclei for two months in 2013 and used lead–lead collisions for about one month each in 2010, 2011 and 2013. After the end of the 2012-2013 run, the LHC went into shutdown for upgrades to increase beam energy to 6.5 TeV per beam and commissioning of the equipment with beam began in April 2015.[21]

Background

The term hadron refers to composite particles composed of quarks held together by the strong force (as atoms and molecules are held together by the electromagnetic force). The best-known hadrons are the baryons protons and neutrons; hadrons also include mesons such as the pion and kaon, which were discovered during cosmic ray experiments in the late 1940s and early 1950s.A collider is a type of a particle accelerator with two directed beams of particles. In particle physics colliders are used as a research tool: they accelerate particles to very high kinetic energies and let them impact other particles. Analysis of the byproducts of these collisions gives scientists good evidence of the structure of the subatomic world and the laws of nature governing it. Many of these byproducts are produced only by high energy collisions, and they decay after very short periods of time. Thus many of them are hard or near impossible to study in other ways.

Purpose

Physicists hope that the LHC will help answer some of the fundamental open questions in physics, concerning the basic laws governing the interactions and forces among the elementary objects, the deep structure of space and time, and in particular the interrelation between quantum mechanics and general relativity, where current theories and knowledge are unclear or break down altogether. Data is also needed from high energy particle experiments to suggest which versions of current scientific models are more likely to be correct – in particular to choose between the Standard Model and Higgsless models and to validate their predictions and allow further theoretical development. Many theorists expect new physics beyond the Standard Model to emerge at the TeV energy level, as the Standard Model appears to be unsatisfactory. Issues possibly to be explored by LHC collisions include:[22][23]- Are the masses of elementary particles actually generated by the Higgs mechanism via electroweak symmetry breaking?[24] It is expected that the collider will either demonstrate or rule out the existence of the elusive Higgs boson, thereby allowing physicists to consider whether the Standard Model or its Higgsless alternatives are more likely to be correct.[25][26][27]

- Is supersymmetry, an extension of the Standard Model and Poincaré symmetry, realized in nature, implying that all known particles have supersymmetric partners?[28][29][30]

- Are there extra dimensions,[31] as predicted by various models based on string theory, and can we detect them?[32]

- What is the nature of the dark matter that appears to account for 27% of the mass-energy of the universe?

- It is already known that electromagnetism and the weak nuclear force are different manifestations of a single force called the electroweak force. The LHC may clarify whether the electroweak force and the strong nuclear force are similarly just different manifestations of one universal unified force, as predicted by various Grand Unification Theories.

- Why is the fourth fundamental force (gravity) so many orders of magnitude weaker than the other three fundamental forces? See also Hierarchy problem.

- Are there additional sources of quark flavour mixing, beyond those already present within the Standard Model?

- Why are there apparent violations of the symmetry between matter and antimatter? See also CP violation.

- What are the nature and properties of quark–gluon plasma, believed to have existed in the early universe and in certain compact and strange astronomical objects today? This will be investigated by heavy ion collisions, mainly in ALICE.

Design

A Feynman diagram of one way the Higgs boson may be produced at the LHC. Here, two quarks each emit a W or Z boson, which combine to make a neutral Higgs.

The LHC is the world's largest and highest-energy particle accelerator.[5][33] The collider is contained in a circular tunnel, with a circumference of 27 kilometres (17 mi), at a depth ranging from 50 to 175 metres (164 to 574 ft) underground.

The 3.8-metre (12 ft) wide concrete-lined tunnel, constructed between 1983 and 1988, was formerly used to house the Large Electron–Positron Collider.[34] It crosses the border between Switzerland and France at four points, with most of it in France. Surface buildings hold ancillary equipment such as compressors, ventilation equipment, control electronics and refrigeration plants.

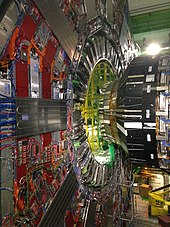

The collider tunnel contains two adjacent parallel beamlines (or beam pipes) that intersect at four points, each containing a proton beam, which travel in opposite directions around the ring. Some 1,232 dipole magnets keep the beams on their circular path (see image[35]), while an additional 392 quadrupole magnets are used to keep the beams focused, in order to maximize the chances of interaction between the particles in the four intersection points, where the two beams cross. In total, over 1,600 superconducting magnets are installed, with most weighing over 27 tonnes.[36] Approximately 96 tonnes of superfluid helium 4 is needed to keep the magnets, made of copper-clad niobium-titanium, at their operating temperature of 1.9 K (−271.25 °C), making the LHC the largest cryogenic facility in the world at liquid helium temperature.

Superconducting quadrupole electromagnets are used to direct the beams to four intersection points, where interactions between accelerated protons will take place.

When running at full design power of 7 TeV per beam, once or twice a day, as the protons are accelerated from 450 GeV to 7 TeV, the field of the superconducting dipole magnets will be increased from 0.54 to 8.3 teslas (T). The protons will each have an energy of 7 TeV, giving a total collision energy of 14 TeV. At this energy the protons have a Lorentz factor of about 7,500 and move at about 0.999999991 c, or about 3 metres per second slower than the speed of light (c).[37] It will take less than 90 microseconds (μs) for a proton to travel once around the main ring – a speed of about 11,000 revolutions per second. Rather than continuous beams, the protons will be bunched together, into up to 2,808 bunches, with 115 billion protons in each bunch so that interactions between the two beams will take place at discrete intervals never shorter than 25 nanoseconds (ns) apart, providing a bunch collision rate of 40 MHz. However it will be operated with fewer bunches when it is first commissioned, giving it a bunch crossing interval of 75 ns.[38] The design luminosity of the LHC is 1034 cm−2s−1.[39]

Prior to being injected into the main accelerator, the particles are prepared by a series of systems that successively increase their energy. The first system is the linear particle accelerator LINAC 2 generating 50-MeV protons, which feeds the Proton Synchrotron Booster (PSB). There the protons are accelerated to 1.4 GeV and injected into the Proton Synchrotron (PS), where they are accelerated to 26 GeV. Finally the Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS) is used to further increase their energy to 450 GeV before they are at last injected (over a period of several minutes) into the main ring. Here the proton bunches are accumulated, accelerated (over a period of 20 minutes) to their peak energy, and finally circulated for 5 to 24 hours while collisions occur at the four intersection points.[40]

The LHC physics program is mainly based on proton–proton collisions. However, shorter running periods, typically one month per year, with heavy-ion collisions are included in the program. While lighter ions are considered as well, the baseline scheme deals with lead ions[41] (see A Large Ion Collider Experiment). The lead ions are first accelerated by the linear accelerator LINAC 3, and the Low-Energy Ion Ring (LEIR) is used as an ion storage and cooler unit. The ions are then further accelerated by the PS and SPS before being injected into LHC ring, where they reached an energy of 1.58 TeV per nucleon (or 328 TeV per ion), higher than the energies reached by the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider. The aim of the heavy-ion program is to investigate quark–gluon plasma, which existed in the early universe.

Detectors

Seven detectors have been constructed at the LHC, located underground in large caverns excavated at the LHC's intersection points. Two of them, the ATLAS experiment and the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS), are large, general purpose particle detectors.[33] ALICE and LHCb have more specific roles and the last three, TOTEM, MoEDAL and LHCf, are very much smaller and are for very specialized research. The BBC's summary of the main detectors is:[42]| Detector | Description |

|---|---|

| ATLAS | One of two general purpose detectors. ATLAS will be used to look for signs of new physics, including the origins of mass and extra dimensions. |

| CMS | The other general purpose detector will, like ATLAS, hunt for the Higgs boson and look for clues to the nature of dark matter. |

| ALICE | ALICE is studying a "fluid" form of matter called quark–gluon plasma that existed shortly after the Big Bang. |

| LHCb | Equal amounts of matter and antimatter were created in the Big Bang. LHCb will try to investigate what happened to the "missing" antimatter. |

Computing and analysis facilities

The LHC Computing Grid is an international collaborative project that consists of a grid-based computer network infrastructure initially connecting 140 computing centers in 35 countries (over 170 in 36 countries as of 2012). It was designed by CERN to handle the significant volume of data produced by LHC experiments.[7][8]By 2012 data from over 6 quadrillion (6 x 1015) LHC proton-proton collisions had been analyzed,[43] LHC collision data was being produced at approximately 25 petabytes per year, and the LHC Computing Grid had become the world's largest computing grid (as of 2012), comprising over 170 computing facilities in a worldwide network across 36 countries.[9][10][11]

Operational history

Inaugural tests

The first beam was circulated through the collider on the morning of 10 September 2008.[42] CERN successfully fired the protons around the tunnel in stages, three kilometres at a time. The particles were fired in a clockwise direction into the accelerator and successfully steered around it at 10:28 local time.[44] The LHC successfully completed its major test: after a series of trial runs, two white dots flashed on a computer screen showing the protons travelled the full length of the collider. It took less than one hour to guide the stream of particles around its inaugural circuit.[45] CERN next successfully sent a beam of protons in a counterclockwise direction, taking slightly longer at one and a half hours due to a problem with the cryogenics, with the full circuit being completed at 14:59.2008 quench incident

On 19 September 2008, a magnet quench occurred in about 100 bending magnets in sectors 3 and 4, where an electrical fault led to a loss of approximately six tonnes of liquid helium (the magnets' cryogenic coolant), which was vented into the tunnel. The escaping vapor expanded with explosive force, damaging over 50 superconducting magnets and their mountings, and contaminating the vacuum pipe, which also lost vacuum conditions.[13][14][46]Shortly after the incident CERN reported that the most likely cause of the problem was a faulty electrical connection between two magnets, and that – due to the time needed to warm up the affected sectors and then cool them back down to operating temperature – it would take at least two months to fix.[47] CERN released an interim technical report[46] and preliminary analysis of the incident on 15 and 16 October 2008 respectively,[48] and a more detailed report on 5 December 2008.[49] The analysis of the incident by CERN confirmed that an electrical fault had indeed been the cause. The faulty electrical connection had led (correctly) to a failsafe power abort of the electrical systems powering the superconducting magnets, but had also caused an electric arc (or discharge) which damaged the integrity of the supercooled helium's enclosure and vacuum insulation, causing the coolant's temperature and pressure to rapidly rise beyond the ability of the safety systems to contain it,[46] and leading to a temperature rise of about 100 degrees Celsius in some of the affected magnets. Energy stored in the superconducting magnets and electrical noise induced in other quench detectors also played a role in the rapid heating. Around two tonnes of liquid helium escaped explosively before detectors triggered an emergency stop, and a further four tonnes leaked at lower pressure in the aftermath.[46] A total of 53 magnets were damaged in the incident and were repaired or replaced during the winter shutdown.[50]

In the original timeline of the LHC commissioning, the first "modest" high-energy collisions at a center-of-mass energy of 900 GeV were expected to take place before the end of September 2008, and the LHC was expected to be operating at 10 TeV by the end of 2008.[51] However, due to the delay caused by the above-mentioned incident, the collider was not operational until November 2009.[52] Despite the delay, LHC was officially inaugurated on 21 October 2008, in the presence of political leaders, science ministers from CERN's 20 Member States, CERN officials, and members of the worldwide scientific community.[53]

Most of 2009 was spent on repairs and reviews from the damage caused by the quench incident, along with two further vacuum leaks identified in July 2009 which pushed the start of operations to November of that year.[54]

Full operation

On 20 November 2009, low-energy beams circulated in the tunnel for the first time since the incident, and shortly after, on 30 November, the LHC achieved 1.18 TeV per beam to become the world's highest-energy particle accelerator, beating the Tevatron's previous record of 0.98 TeV per beam held for eight years.[55]The early part of 2010 saw the continued ramp-up of beam in energies and early physics experiments towards 3.5 TeV per beam and on 30 March 2010, LHC set a new record for high-energy collisions by colliding proton beams at a combined energy level of 7 TeV. The attempt was the third that day, after two unsuccessful attempts in which the protons had to be "dumped" from the collider and new beams had to be injected.[56] This also marked the start of its main research program.

The first proton run ended on 4 November 2010. A run with lead ions started on 8 November 2010, and ended on 6 December 2010,[57] allowing the ALICE experiment to study matter under extreme conditions similar to those shortly after the Big Bang.[58]

CERN originally planned that the LHC would run through to the end of 2012, with a short break at the end of 2011 to allow for an increase in beam energy from 3.5 to 4 TeV per beam.[20] At the end of 2012 the LHC was shut down until around 2015 to allow upgrade to a planned beam energy of 7 TeV per beam.[59] In late 2012, in light of the July 2012 discovery of a new particle, the shutdown was postponed for some weeks into early 2013, to allow additional data to be obtained prior to shutdown.

On 5 April 2015 the LHC was restarted after a two-year break.[21] Although particle beams have travelled in both directions, inside parallel pipes, actual collisions are expected to begin in May.[21]

Timeline of operations

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 10 Sep 2008 | CERN successfully fired the first protons around the entire tunnel circuit in stages. |

| 19 Sep 2008 | Magnetic quench occurred in about 100 bending magnets in sectors 3 and 4, causing a loss of approximately 6 tonnes of liquid helium. |

| 30 Sep 2008 | First "modest" high-energy collisions planned but postponed due to accident.[36] |

| 16 Oct 2008 | CERN released a preliminary analysis of the accident. |

| 21 Oct 2008 | Official inauguration. |

| 5 Dec 2008 | CERN released detailed analysis. |

| 20 Nov 2009 | Low-energy beams circulated in the tunnel for the first time since the accident.[60] |

| 23 Nov 2009 | First particle collisions in all four detectors at 450 GeV. |

| 30 Nov 2009 | LHC becomes the world's highest-energy particle accelerator achieving 1.18 TeV per beam, beating the Tevatron's previous record of 0.98 TeV per beam held for eight years.[55] |

| 15 Dec 2009 | First scientific results, covering 284 collisions in the ALICE detector.[61] |

| early Feb 2010 | First proton-proton collisions beyond FermiLab's energies, published by the CMS team.[62] |

| 28 Feb 2010 | The LHC continues operations ramping energies to run at 3.5 TeV for 18 months to two years, after which it will be shut down to prepare for the 14 TeV collisions (7 TeV per beam).[63] |

| 30 Mar 2010 | The two beams collided at 7 TeV (3.5 TeV per beam) in the LHC at 13:06 CEST, marking the start of the LHC research program. |

| 8 Nov 2010 | Start of the first run with lead ions. |

| 6 Dec 2010 | End of the run with lead ions. Shutdown until early 2011. |

| 13 Mar 2011 | Beginning of the 2011 run with proton beams.[64] |

| 21 Apr 2011 | LHC becomes the world's highest-luminosity hadron accelerator achieving a peak luminosity of 4.67·1032 cm−2s−1, beating the Tevatron's previous record of 4·1032 cm−2s−1 held for one year.[65] |

| 24 May 2011 | Quark–gluon plasma achieved.[66] |

| 17 Jun 2011 | The high luminosity experiments ATLAS and CMS reach 1 fb−1 of collected data.[67] |

| 14 Oct 2011 | LHCb reaches 1 fb−1 of collected data.[68] |

| 23 Oct 2011 | The high luminosity experiments ATLAS and CMS reach 5 fb−1 of collected data. |

| Nov 2011 | Second run with lead ions. |

| 22 Dec 2011 | First new composite particle discovery, the χb (3P) bottomonium meson, observed with proton-proton collisions in 2011.[69] |

| 5 Apr 2012 | First collisions with stable beams in 2012 after the winter shutdown. The energy is increased to 4 TeV per beam (8 TeV in collisions).[70] |

| 4 Jul 2012 | First new elementary particle discovery, a new boson observed that is "consistent with" the theorized Higgs boson. (This has now been confirmed as the Higgs boson itself.[71]) |

| 8 Nov 2012 | First observation of the very rare decay of the Bs meson into two muons (Bs0 → μ+μ−), a major test of supersymmetry theories,[72] shows results at 3.5 sigma that match the Standard Model rather than many of its super-symmetrical variants. |

| 20 Jan 2013 | Start of the first run colliding protons with Lead ions. |

| 11 Feb 2013 | End of the first run colliding protons with Lead ions. |

| 14 Feb 2013 | Beginning of the first long shutdown, to prepare the collider for a higher energy and luminosity. When reactivated in early 2015, the LHC will operate with an energy of 13 TeV, almost double its current maximum energy.[73] |

| 7 Mar 2015 | Injection tests for Run 2 send protons towards LHCb & ALICE |

| 5 Apr 2015 | Begin commissioning with beam circulating in the collider[21] |

Findings

CERN scientists estimated that, if the Standard Model is correct, several Higgs bosons would be produced every minute, and that over a few years enough data to confirm or disprove the Higgs boson unambiguously and to obtain sufficient results concerning supersymmetric particles would be gathered to draw meaningful conclusions.[5] Some extensions of the Standard Model predict additional particles, such as the heavy W' and Z' gauge bosons, which may also lie within reach of the LHC to discover.[74]The first physics results from the LHC, involving 284 collisions which took place in the ALICE detector, were reported on 15 December 2009.[61] The results of the first proton–proton collisions at energies higher than Fermilab's Tevatron proton–antiproton collisions were published by the CMS collaboration in early February 2010, yielding greater-than-predicted charged-hadron production.[62]

After the first year of data collection, the LHC experimental collaborations started to release their preliminary results concerning searches for new physics beyond the Standard Model in proton-proton collisions.[75][76][77][78] No evidence of new particles was detected in the 2010 data. As a result, bounds were set on the allowed parameter space of various extensions of the Standard Model, such as models with large extra dimensions, constrained versions of the Minimal Supersymmetric Standard Model, and others.[79][80][81]

On 24 May 2011, it was reported that quark–gluon plasma (the densest matter besides black holes) has been created in the LHC.[66]

Between July and August 2011, results of searches for the Higgs boson and for exotic particles, based on the data collected during the first half of the 2011 run, were presented in conferences in Grenoble[82] and Mumbai.[83] In the latter conference it was reported that, despite hints of a Higgs signal in earlier data, ATLAS and CMS exclude with 95% confidence level (using the CLs method) the existence of a Higgs boson with the properties predicted by the Standard Model over most of the mass region between 145 and 466 GeV.[84] The searches for new particles did not yield signals either, allowing to further constrain the parameter space of various extensions of the Standard Model, including its supersymmetric extensions.[85][86]

On 13 December 2011, CERN reported that the Standard Model Higgs boson, if it exists, is most likely to have a mass constrained to the range 115–130 GeV. Both the CMS and ATLAS detectors have also shown intensity peaks in the 124–125 GeV range, consistent with either background noise or the observation of the Higgs boson.[87]

On 22 December 2011, it was reported that a new particle had been observed, the χb (3P) bottomonium state.[69]

On 4 July 2012, both the CMS and ATLAS teams announced the discovery of a boson in the mass region around 125–126 GeV, with a statistical significance at the level of 5 sigma. This meets the formal level required to announce a new particle which is consistent with the Higgs boson, but scientists were cautious as to whether it is formally identified as actually being the Higgs boson, pending further analysis.[88]

On 8 November 2012, the LHCb team reported on an experiment seen as a "golden" test of supersymmetry theories in physics,[72] by measuring the very rare decay of the Bs meson into two muons (Bs0 → μ+μ−). The results, which match those predicted by the non-supersymmetrical Standard Model rather than the predictions of many branches of supersymmetry, show the decays are less common than some forms of supersymmetry predict, though could still match the predictions of other versions of supersymmetry theory. The results as initially drafted are stated to be short of proof but at a relatively high 3.5 sigma level of significance.[89] The result was later confirmed by the CMS collaboration.[90]

In August 2013 the team revealed an anomaly in the angular distribution of B meson decay products which could not be predicted by the Standard Model; this anomaly had a statistical certainty of 4.5 sigma, just short of the 5 sigma needed to be officially recognized as a discovery. It is unknown what the cause of this anomaly would be, although the Z' boson has been suggested as a possible candidate.[91]

On 19 November 2014, the LHCb experiment announced the discovery of two new heavy subatomic particles, Ξ′−

b and Ξ∗−

b. Both of them are baryons that are composed of one bottom, one down, and one strange quark. They are excited states of the bottom Xi baryon.[92][93]

Proposed upgrade

After some years of running, any particle physics experiment typically begins to suffer from diminishing returns: as the key results reachable by the device begin to be completed, later years of operation discover proportionately less than earlier years. A common outcome is to upgrade the devices involved, typically in energy, in luminosity, or in terms of improved detectors. As well as the planned 2013–2015 increase to its intended 14 TeV collision energy, a luminosity upgrade of the LHC, called the High Luminosity LHC, has also been proposed,[94] to be made in 2022.The optimal path for the LHC luminosity upgrade includes an increase in the beam current (i.e. the number of protons in the beams) and the modification of the two high-luminosity interaction regions, ATLAS and CMS. To achieve these increases, the energy of the beams at the point that they are injected into the (Super) LHC should also be increased to 1 TeV. This will require an upgrade of the full pre-injector system, the needed changes in the Super Proton Synchrotron being the most expensive. Currently the collaborative research effort of LHC Accelerator Research Program, LARP, is conducting research into how to achieve these goals.[95]Cost

With a budget of 7.5 billion euros (approx. $9bn or £6.19bn as of June 2010), the LHC is one of the most expensive scientific instruments[96] ever built.[97] The total cost of the project is expected to be of the order of 4.6bn Swiss francs (SFr) (approx. $4.4bn, €3.1bn, or £2.8bn as of Jan 2010) for the accelerator and 1.16bn (SFr) (approx. $1.1bn, €0.8bn, or £0.7bn as of Jan 2010) for the CERN contribution to the experiments.[98]The construction of LHC was approved in 1995 with a budget of SFr 2.6bn, with another SFr 210M towards the experiments. However, cost overruns, estimated in a major review in 2001 at around SFr 480M for the accelerator, and SFr 50M for the experiments, along with a reduction in CERN's budget, pushed the completion date from 2005 to April 2007.[99] The superconducting magnets were responsible for SFr 180M of the cost increase. There were also further costs and delays due to engineering difficulties encountered while building the underground cavern for the Compact Muon Solenoid,[100] and also due to faulty parts provided by Fermilab.[101] Due to lower electricity costs during the summer, the LHC normally does not operate over the winter months,[102] although an exception over the 2009/10 winter was made to make up for the 2008 start-up delays.

Computing resources

Data produced by LHC, as well as LHC-related simulation, was estimated at approximately 15 petabytes per year (max throughput while running not stated).[103]The LHC Computing Grid[104] was constructed to handle the massive amounts of data produced. It incorporated both private fiber optic cable links and existing high-speed portions of the public Internet, enabling data transfer from CERN to academic institutions around the world.[105]

The Open Science Grid is used as the primary infrastructure in the United States, and also as part of an interoperable federation with the LHC Computing Grid.

The distributed computing project LHC@home was started to support the construction and calibration of the LHC. The project uses the BOINC platform, enabling anybody with an Internet connection and a computer running Mac OS X, Windows or Linux,[106] to use their computer's idle time to simulate how particles will travel in the tunnel. With this information, the scientists will be able to determine how the magnets should be calibrated to gain the most stable "orbit" of the beams in the ring.[107] In August 2011, a second application went live (Test4Theory) which performs simulations against which to compare actual test data, to determine confidence levels of the results.

Safety of particle collisions

The experiments at the Large Hadron Collider sparked fears that the particle collisions might produce doomsday phenomena, involving the production of stable microscopic black holes or the creation of hypothetical particles called strangelets.[108] Two CERN-commissioned safety reviews examined these concerns and concluded that the experiments at the LHC present no danger and that there is no reason for concern,[109][110][111] a conclusion expressly endorsed by the American Physical Society.[112]The reports also noted that the physical conditions and collision events which exist in the LHC and similar experiments occur naturally and routinely in the universe without hazardous consequences,[110] including ultra-high-energy cosmic rays observed to impact Earth with energies far higher than those in any man-made collider.

Operational challenges

The size of the LHC constitutes an exceptional engineering challenge with unique operational issues on account of the amount of energy stored in the magnets and the beams.[40][113] While operating, the total energy stored in the magnets is 10 GJ (2,400 kilograms of TNT) and the total energy carried by the two beams reaches 724 MJ (173 kilograms of TNT).[114]Loss of only one ten-millionth part (10−7) of the beam is sufficient to quench a superconducting magnet, while the beam dump must absorb 362 MJ (87 kilograms of TNT) for each of the two beams. These energies are carried by very little matter: under nominal operating conditions (2,808 bunches per beam, 1.15×1011 protons per bunch), the beam pipes contain 1.0×10−9 gram of hydrogen, which, in standard conditions for temperature and pressure, would fill the volume of one grain of fine sand.

Construction accidents and delays

- On 25 October 2005, José Pereira Lages, a technician, was killed in the LHC when a switchgear that was being transported fell on him.[115]

- On 27 March 2007 a cryogenic magnet support broke during a pressure test involving one of the LHC's inner triplet (focusing quadrupole) magnet assemblies, provided by Fermilab and KEK. No one was injured. Fermilab director Pier Oddone stated "In this case we are dumbfounded that we missed some very simple balance of forces". This fault had been present in the original design, and remained during four engineering reviews over the following years.[116] Analysis revealed that its design, made as thin as possible for better insulation, was not strong enough to withstand the forces generated during pressure testing. Details are available in a statement from Fermilab, with which CERN is in agreement.[117][118] Repairing the broken magnet and reinforcing the eight identical assemblies used by LHC delayed the startup date, then planned for November 2007.

- Problems occurred on 19 September 2008 during powering tests of the main dipole circuit, when an electrical fault in the bus between magnets caused a rupture and a leak of six tonnes of liquid helium. The operation was delayed for several months.[119] It is currently believed that a faulty electrical connection between two magnets caused an arc, which compromised the liquid-helium containment. Once the cooling layer was broken, the helium flooded the surrounding vacuum layer with sufficient force to break 10-ton magnets from their mountings. The explosion also contaminated the proton tubes with soot.[49][120] This accident was thoroughly discussed in a 22 February 2010 Superconductor Science and Technology article by CERN physicist Lucio Rossi.[121]

- Two vacuum leaks were identified in July 2009, and the start of operations was further postponed to mid-November 2009.[54]

Popular culture

The Large Hadron Collider gained a considerable amount of attention from outside the scientific community and its progress is followed by most popular science media. The LHC has also inspired works of fiction including novels, TV series, video games and films.The novel Angels & Demons, by Dan Brown, involves antimatter created at the LHC to be used in a weapon against the Vatican. In response CERN published a "Fact or Fiction?" page discussing the accuracy of the book's portrayal of the LHC, CERN, and particle physics in general.[122] The movie version of the book has footage filmed on-site at one of the experiments at the LHC; the director, Ron Howard, met with CERN experts in an effort to make the science in the story more accurate.[123]

The novel FlashForward, by Robert J. Sawyer, involves the search for the Higgs boson at the LHC. CERN published a "Science and Fiction" page interviewing Sawyer and physicists about the book and the TV series based on it.[124]

CERN employee Katherine McAlpine's "Large Hadron Rap"[125] surpassed 7 million YouTube views.[126][127] The band Les Horribles Cernettes was founded by women from CERN. The name was chosen so to have the same initials as the LHC.[128][129]

National Geographic Channel's World's Toughest Fixes, Season 2 (2010), Episode 6 "Atom Smasher" features the replacement of the last superconducting magnet section in the repair of the supercollider after the 2008 quench incident. The episode includes actual footage from the repair facility to the inside of the supercollider, and explanations of the function, engineering, and purpose of the LHC.[130]

The Large Hadron Collider was the focus of the 2012 student film Decay, with the movie being filmed on location in CERN's maintenance tunnels.[131]

The third season of the popular CBS sitcom "The Big Bang Theory" features an episode revolving around a dilemma regarding a trip to Switzerland to see the Large Hadron Collider.

The feature documentary Particle Fever follows the experimental physicists at CERN who run the experiments, as well as the theoretical physicists who attempt to provide a conceptual framework for the LHC's results. It won the Sheffield International Doc/Fest in 2013.

Onion News Network featured a parodied news story about the LHC titled "Bored Scientists Now Just Sticking Random Things Into Large Hadron Collider".

In the Japanese visual novel Steins;Gate developed by 5pb. and Nitroplus, the Large Hadron Collider is utilized by the game′s parody of CERN, named SERN, for time travel, and eventual world domination.[132]