| Freeman Dyson |

|

| Born |

Freeman John Dyson

(1923-12-15) 15 December 1923 (age 91)

Crowthorne, Berkshire, England |

| Nationality |

British |

| Fields |

Physics, Mathematics |

| Institutions |

Royal Air Force

Institute for Advanced Study

University of Birmingham

Duke University

Cornell University |

| Alma mater |

Trinity College, Cambridge, Cornell University[1] |

| Academic advisors |

Hans Bethe |

| Known for |

Dyson sphere

Dyson operator

Dyson series

Schwinger-Dyson equation

Circular ensemble

Random Matrix Theory

Advocacy against nuclear weapons

Dyson conjecture

Dyson's eternal intelligence

Dyson number

Dyson tree

Dyson's transform

Project Orion

TRIGA |

| Influences |

Richard Feynman,[2][3][full citation needed] Abram Samoilovitch Besicovitch[4] |

| Notable awards |

Heineman Prize (1965)

Lorentz Medal (1966)

Hughes Medal (1968)

Harvey Prize (1977)

Wolf Prize (1981)

Andrew Gemant Award (1988)

Matteucci Medal (1989)

Oersted Medal (1991)

Fermi Award (1993)

Templeton Prize (2000)

Pomeranchuk Prize (2003)

Poincaré Prize (2012) |

| Children |

Esther Dyson, George Dyson, Dorothy Dyson, Mia Dyson, Rebecca Dyson, Emily Dyson |

Website

http://www.sns.ias.edu/dyson |

| Notes |

|

|

Freeman John Dyson FRS (born 15 December 1923) is an

English-born[5][6] theoretical

physicist and

mathematician, known for his work in

quantum electrodynamics,

solid-state physics,

astronomy and

nuclear engineering. Dyson is a member of the Board of Sponsors of the

Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

[7]

Biography

Early life

Born at

Crowthorne in

Berkshire, Dyson is the son of the English composer

George Dyson, who was later knighted.

His mother had a law degree, but after Dyson was born she worked as a social worker.

[8] Although not known to be related to the early 20th-century astronomer

Frank Watson Dyson, as a small boy Dyson was aware of him and has credited the popularity of an astronomer sharing his surname as having helped to spark his own interest in science.

[citation needed] At the age of five he calculated the number of atoms in the sun.

[9] As a child, he showed an interest in large numbers and in the solar system, and was strongly influenced by the book

Men of Mathematics by

Eric Temple Bell.

[2]

From 1936 to 1941, Dyson was a Scholar at

Winchester College, where his father was Director of Music. On 25 July 1943, he entered the

Operational Research Section (ORS) of the Royal Air Force’s

Bomber Command,

[10] where he developed analytical methods to help the Royal Air Force to bomb German targets during the

Second World War.

[11] After the war, Dyson was admitted to

Trinity College, Cambridge,

[12] where he obtained a

Bachelor of Arts degree in mathematics.

[13] From 1946 to 1949 he was a

Fellow of his college, occupying rooms just below those of the philosopher

Ludwig Wittgenstein, who resigned his professorship in 1947.

[14] In 1947 he published two papers in

Number theory[15] [16]

Career in the United States

In 1947 Dyson moved to the US, as Commonwealth Fellow at

Cornell University (1947–1948) and the

Institute for Advanced Study (1948–1949). Between 1949 and 1951, he was a teaching fellow at the

University of Birmingham (UK).

[17]

In 1951 he joined the faculty at Cornell as a physics professor, although still lacking a doctorate, and in 1953 he received a permanent post at the Institute for Advanced Study in

Princeton, New Jersey—where he has now lived for more than fifty years.

[18] In 1957 he became a

naturalized citizen of the United States and renounced his

British nationality. One reason he gave decades later is that his children born in the US had not been recognized as British subjects.

[5][6]

Dyson is best known for demonstrating in 1949 the equivalence of two then-current formulations of

quantum electrodynamics—

Richard Feynman's diagrams and the operator method developed by

Julian Schwinger and

Sin-Itiro Tomonaga.

[19] He was the first person (besides Feynman) to appreciate the power of

Feynman diagrams, and his paper written in 1948 and published in 1949 was the first to make use of them. He said in that paper that Feynman diagrams were not just a computational tool, but a physical theory, and developed rules for the diagrams that completely solved the

renormalization problem. Dyson's paper and also his lectures presented Feynman's theories of QED (quantum electrodynamics) in a form that other physicists could understand, facilitating the physics community's acceptance of Feynman's work.

Robert Oppenheimer, in particular, was persuaded by Dyson that Feynman's new theory was as valid as Schwinger's and Tomonaga's. Oppenheimer rewarded Dyson with a lifetime appointment at the Institute for Advanced Study, "for proving me wrong", in Oppenheimer's words.

[20]

Also in 1949, in a related work, Dyson invented the

Dyson series.

[21] It was this paper that inspired

John Ward to derive his celebrated

Ward identity.

[22]

Dyson also did work in a variety of topics in mathematics, such as topology, analysis, number theory and random matrices.

[23] There is an interesting story involving random matrices. In 1973 the number theorist

Hugh Montgomery was visiting the Institute for Advanced Study and had just made his

pair correlation conjecture concerning the distribution of the zeros of the

Riemann zeta function. He showed his formula to the mathematician

Atle Selberg who said it looked like something in

mathematical physics and he should show it to Dyson, which he did. Dyson recognized the formula as the

pair correlation function of the

Gaussian unitary ensemble, which has been extensively studied by physicists. This suggested that there might be an unexpected connection between the

distribution of primes 2,3,5,7,11, ... and the energy levels in the

nuclei of

heavy elements such as

uranium.

[24]

From 1957 to 1961 he worked on the

Orion Project, which proposed the possibility of space-flight using

nuclear pulse propulsion. A prototype was demonstrated using

conventional explosives, but the 1963

Partial Test Ban Treaty (which Dyson was involved in and supported) permitted only

underground nuclear testing, so the project was abandoned.

In 1958 he led the design team for the

TRIGA, a small, inherently safe

nuclear reactor used throughout the world in hospitals and universities for the production of

medical isotopes.

A seminal work by Dyson came in 1966 when, together with Andrew Lenard and independently of

Elliott H. Lieb and

Walter Thirring, he proved rigorously that the

exclusion principle plays the main role in the stability of bulk matter.

[25][26][27] Hence, it is not the electromagnetic repulsion between outer-shell orbital electrons which prevents two wood blocks that are left on top of each other from coalescing into a single piece, but rather it is the exclusion principle applied to electrons and protons that generates the classical macroscopic

normal force. In

condensed matter physics, Dyson also did studies in the phase transition of the

Ising model in 1 dimension and

spin waves.

[23]

Around 1979, Dyson worked with the

Institute for Energy Analysis on

climate studies. This group, under the direction of

Alvin Weinberg, pioneered multidisciplinary climate studies, including a strong biology group. Also during the 1970s, he worked on climate studies conducted by the

JASON defense advisory group.

[18]

Dyson retired from the Institute for Advanced Study in 1994.

[28] In 1998, Dyson joined the board of the

Solar Electric Light Fund. As of 2003

[update] he was president of the

Space Studies Institute, the space research organization founded by

Gerard K. O'Neill; As of 2013

[update] he is on its Board of Trustees.

[29] Dyson is a long-time member of the JASON group.

Dyson is a regular contributor to

The New York Review of Books.

Dyson has won numerous scientific awards but never a

Nobel Prize. Nobel physics laureate

Steven Weinberg has said that the

Nobel committee has "fleeced" Dyson, but Dyson himself remarked in 2009, "I think it's almost true without exception if you want to win a Nobel Prize, you should have a long attention span, get hold of some deep and important problem and stay with it for ten years. That wasn't my style."

[18]

In 2012, he published (with

William H. Press) a fundamental new result about the

Prisoner's Dilemma in

PNAS.

[30]

Marriages and children

With his first wife, the mathematician

Verena Huber-Dyson, Dyson has two children,

Esther and

George. In 1958 he married Imme Jung, a

masters runner, and they eventually had four more children, Dorothy, Mia, Rebecca, and Emily Dyson.

[18]

Dyson's eldest daughter, Esther, is a digital technology consultant and investor; she has been called "the most influential woman in all the computer world."

[31] His son George is a

historian of science,

[32] one of whose books is

Project Orion: The Atomic Spaceship 1957–1965.

Character

Friends and colleagues describe Dyson as shy and self-effacing, with a contrarian streak that his friends find refreshing but his intellectual opponents find exasperating. "I have the sense that when consensus is forming like ice hardening on a lake, Dyson will do his best to chip at the ice",

Steven Weinberg said of him. His friend, the neurologist and author

Oliver Sacks, said: "A favorite word of Freeman's about doing science and being creative is the word 'subversive'. He feels it's rather important not only to be not orthodox, but to be subversive, and he's done that all his life."

[18] [clarification needed] In

The God Delusion (2006), biologist

Richard Dawkins criticized Dyson for accepting the religious

Templeton Prize in 2000; "It would be taken as an endorsement of religion by one of the world's most distinguished physicists."

[33] However, Dyson declared in 2000 that he is a (non-denominational) Christian,

[34] and he has disagreed with Dawkins on several occasions, as when he criticized Dawkins' understanding of

evolution.

[35]

Honors and awards

In 1952 he was elected a

Fellow of the Royal Society.

[36]

Dyson was awarded the

Lorentz Medal in 1966,

Max Planck Medal in 1969, the

J. Robert Oppenheimer Memorial Prize in 1970,

[37][38] and the

Harvey Prize in 1977.

In the 1984–85 academic year he gave the

Gifford lectures at

Aberdeen, which resulted in the book

Infinite In All Directions.

In 1989, Dyson taught at

Duke University as a

Fritz London Memorial Lecturer. In the same year, he was elected as an Honorary Fellow of Trinity College, University of Cambridge.

Dyson has published a number of collections of speculations and observations about technology, science, and the future. In 1996 he was awarded the

Lewis Thomas Prize for Writing about Science.

In 1993, Dyson was given the

Enrico Fermi Award.

In 1995 he gave the Jerusalem-Harvard Lectures at the

Hebrew University of Jerusalem, sponsored jointly by the Hebrew University and

Harvard University Press that grew into the book

Imagined Worlds.

[39]

In 2000, Dyson was awarded the

Templeton Prize for Progress in Religion.

In 2003, Dyson was awarded the Telluride Tech Festival Award of Technology in

Telluride, Colorado.

In 2011, Dyson was received as one of twenty distinguished

Old Wykehamists at the

Ad Portas celebration, the highest honour that

Winchester College bestows.

Concepts

Biotechnology and genetic engineering

My book The Sun, the Genome, and the Internet (1999) describes a vision of green technology enriching villages all over the world and halting the migration from villages to megacities. The three components of the vision are all essential: the sun to provide energy where it is needed, the genome to provide plants that can convert sunlight into chemical fuels cheaply and efficiently, the Internet to end the intellectual and economic isolation of rural populations. With all three components in place, every village in Africa could enjoy its fair share of the blessings of civilization.[40]

Dyson cheerfully admits his record as a prophet is mixed, but "it is better to be wrong than to be vague."

[41]

"To answer the world's material needs, technology has to be not only beautiful but also cheap."

[42]

The Origin of Life

Dyson favors the dual origin concept: Life first formed cells, then enzymes, and finally, much later, genes. This was first propounded by the Russian

Alexander Oparin [43] and unfortunately became mixed up with Marxism and the theories of Lysenko.

J. B. S. Haldane developed the same theory independently, and was also a Marxist.

[44] Dyson has simplified things by saying simply that life evolved in two stages, widely separated in time. He regards it as too unlikely that genes could have developed fully blown in one process, because of the biochemistry. He proposes that in a primitive early cell containing ATP and AMP, DNA was invented accidentally because of the similarity of the two. Current cells contain

Adenosine triphosphate or ATP and

adenosine 5'-monophosphate or AMP, which greatly resemble each other but have completely different functions. ATP transports energy around the cell, and AMP is part of RNA and the genetic apparatus. Dyson proposes that in a primitive early cell containing ATP and AMP, RNA and replication were invented accidentally because of the similarity of the two. He suggests that AMP was produced when ATP molecules lost two of their phosphate radicals, and then one cell somewhere performed

Eigen's experiment and produced RNA.

Unfortunately there is no direct evidence for the dual origin concept, because once genes developed, they took over, obliterating all traces of the earlier forms of life. In the first origin, the cells were probably just drops of water held together by surface tension, teeming with enzymes and chemical reactions, and a primitive kind of growth or replication. When the liquid drop became too big, it split into two drops. Many complex molecules formed in these "little city economies" and the probability that genes would eventually develop in them was much greater than in the prebiotic environment.

[45]

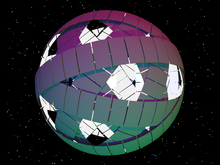

Dyson sphere

Artist's concept of Dyson rings, forming a stable

Dyson swarm, or "Dyson sphere".

One should expect that, within a few thousand years of its entering the stage of industrial development, any intelligent species should be found occupying an artificial biosphere which completely surrounds its parent star.[46]

In 1960 Dyson wrote a short paper for the journal

Science, entitled "Search for Artificial Stellar Sources of Infrared Radiation".

[47] In it, he theorized that a technologically advanced

extraterrestrial civilization might completely surround its native star with artificial structures in order to maximize the capture of the star's available energy. Eventually, the civilization would completely enclose the star, intercepting

electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths from visible light downwards and radiating waste heat outwards as

infrared radiation. Therefore, one method of

searching for extraterrestrial civilizations would be to look for large objects radiating in the infrared range of the

electromagnetic spectrum.

Dyson conceived that such structures would be clouds of

asteroid-sized

space habitats, though

science fiction writers have preferred a solid structure: either way, such an artifact is often referred to as a

Dyson sphere, although Dyson himself used the term "shell". Dyson says that he used the term "artificial biosphere" in the article meaning a habitat, not a shape.

[48] The general concept of such an energy-transferring shell had been advanced decades earlier by author

Olaf Stapledon in his 1937 novel

Star Maker, a source that Dyson has credited publicly.

[49][50]

Dyson tree

Dyson has also proposed the creation of a

Dyson tree, a

genetically-engineered plant capable of growing on a

comet. He suggested that comets could be engineered to contain hollow spaces filled with a breathable atmosphere, thus providing self-sustaining habitats for humanity in the outer

solar system.

Plants could grow greenhouses…just as turtles grow shells and polar bears grow fur and polyps build coral reefs in tropical seas. These plants could keep warm by the light from a distant Sun and conserve the oxygen that they produce by photosynthesis. The greenhouse would consist of a thick skin providing thermal insulation, with small transparent windows to admit sunlight. Outside the skin would be an array of simple lenses, focusing sunlight through the windows into the interior… Groups of greenhouses could grow together to form extended habitats for other species of plants and animals.[51]

Space colonies

I've done some historical research on the costs of the Mayflower's voyage, and on the Mormons' emigration to Utah, and I think it's possible to go into space on a much smaller scale. A cost on the order of $40,000 per person [1978 dollars, $143,254 in 2013 dollars] would be the target to shoot for; in terms of real wages, that would make it comparable to the colonization of America. Unless it's brought down to that level it's not really interesting to me, because otherwise it would be a luxury that only governments could afford.[46]

Dyson has been interested in space travel since he was a child, reading such

science fiction classics as

Olaf Stapledon's

Star Maker. As a young man, he worked for

General Atomics on the nuclear-powered

Orion spacecraft.

He hoped Project Orion would put men on Mars by 1965, Saturn by 1970. He's been unhappy for a quarter-century on how the government conducts space travel:

The problem is, of course, that they can't afford to fail. The rules of the game are that you don't take a chance, because if you fail, then probably your whole program gets wiped out.[46]

He still hopes for cheap space travel, but is resigned to waiting for private entrepreneurs to develop something new—and cheap.

No law of physics or biology forbids cheap travel and settlement all over the solar system and beyond. But it is impossible to predict how long this will take. Predictions of the dates of future achievements are notoriously fallible. My guess is that the era of cheap unmanned missions will be the next fifty years, and the era of cheap manned missions will start sometime late in the twenty-first century.

Any affordable program of manned exploration must be centered in biology, and its time frame tied to the time frame of biotechnology; a hundred years, roughly the time it will take us to learn to grow warm-blooded plants, is probably reasonable.[51]

Dyson also has proposed the use of bioengineered space colonies to colonize the Kuiper Belt on the outer edge of our Solar System. He proposed that habitats could be grown from space hardened spores. The colonies could then be warmed by large reflector plant leaves that could focus the dim, distant sunlight back on the growing colony. This was illustrated by Pat Rawlings on the cover of the National Space Society's Ad Astra magazine.

Space exploration

A direct search for life in Europa's ocean would today be prohibitively expensive. Impacts on Europa give us an easier way to look for evidence of life there. Every time a major impact occurs on Europa, a vast quantity of water is splashed from the ocean into the space around Jupiter. Some of the water evaporates, and some condenses into snow. Creatures living in the water far enough from the impact have a chance of being splashed intact into space and quickly freeze-dried. Therefore, an easy way to look for evidence of life in Europa's ocean is to look for freeze-dried fish in the ring of space debris orbiting Jupiter.

Freeze-dried fish orbiting Jupiter is a fanciful notion, but nature in the biological realm has a tendency to be fanciful. Nature is usually more imaginative than we are. [...] To have the best chance of success, we should keep our eyes open for all possibilities.[51]

Dyson's transform

Dyson also has some credits in pure mathematics. His concept "Dyson's transform" led to one of the most important

lemmas of

Olivier Ramaré's theorem that every even integer can be written as a sum of no more than six primes.

Dyson series

The

Dyson series, the formal solution of an explicitly time-dependent

Schrödinger equation by iteration, and the corresponding Dyson time-ordering operator

an entity of basic importance in the

mathematical formulation of quantum mechanics, are also named after Dyson.

Quantum Physics and the Primes 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, ...

Dyson and

Hugh Montgomery discovered together an intriguing connection between quantum physics and

Montgomery's pair correlation conjecture about the zeros of the Zeta function. The primes 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, ... are described by the

Riemann Zeta function, and Dyson had previously developed a description of quantum physics based on m by m arrays of totally random numbers.

[52] What Montgomery and Dyson discovered is that the

eigenvalues of these matrices are spaced apart in exactly the same manner as Montgomery conjectured for the nontrivial zeros of the Zeta function.

Andrew Odlyzko has verified the conjecture on a computer, using his

Odlyzko–Schönhage algorithm to calculate many zeros. Dyson recognized this connection because of a number-theory question Montgomery asked him. Dyson had published results in

Number theory in 1947 while a Fellow at

Trinity College, Cambridge and so was able to understand Montgomery's question. If Montgomery had not been visiting the

Institute for Advanced Study that week, this connection might not have been discovered.

Views

Metaphysics

Dyson has suggested a kind of cosmic metaphysics of

mind. In his book

Infinite in All Directions he writes about three levels of mind: "The universe shows evidence of the operations of mind on three levels. The first level is the level of elementary physical processes in quantum mechanics. Matter in quantum mechanics is [...] constantly making choices between alternative possibilities according to probabilistic laws. [...] The second level at which we detect the operations of mind is the level of direct human experience. [...] [I]t is reasonable to believe in the existence of a third level of mind, a mental component of the universe. If we believe in this mental component and call it God, then we can say that we are small pieces of God's mental apparatus" (p. 297).

Global warming

Dyson agrees that anthropogenic

global warming exists, and has written that "[one] of the main causes of warming is the increase of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere resulting from our burning of fossil fuels such as oil and coal and natural gas."

[53] However, he believes that existing simulation models of climate fail to account for some important factors, and hence the results will contain too much error to reliably predict future trends:

The models solve the equations of fluid dynamics, and they do a very good job of describing the fluid motions of the atmosphere and the oceans. They do a very poor job of describing the clouds, the dust, the chemistry and the biology of fields and farms and forests. They do not begin to describe the real world we live in ...[53]

He is among signatories of a letter to the UN criticizing the

IPCC[54][55] and has also argued against ostracizing scientists whose views depart from the acknowledged mainstream of

scientific opinion on climate change, stating that "heretics" have historically been an important force in driving scientific progress. "[H]eretics who question the dogmas are needed ... I am proud to be a heretic. The world always needs heretics to challenge the prevailing orthodoxies."

[53]

Dyson says his views on global warming have been strongly criticized. In reply, he notes that "[m]y objections to the global warming propaganda are not so much over the technical facts, about which I do not know much, but it’s rather against the way those people behave and the kind of intolerance to criticism that a lot of them have."

[56]

More recently, he has endorsed the now common usage of "global warming" as synonymous with global anthropogenic climate change, referring to "measurements that transformed global warming from a vague theoretical speculation into a precise observational science."

[57]

He has, however, argued that political efforts to reduce the causes of climate change distract from other global problems that should take priority:

I'm not saying the warming doesn't cause problems, obviously it does. Obviously we should be trying to understand it. I'm saying that the problems are being grossly exaggerated. They take away money and attention from other problems that are much more urgent and important. Poverty, infectious diseases, public education and public health. Not to mention the preservation of living creatures on land and in the oceans.[58]

Since originally taking interest in climate studies in the 1970s, Dyson has suggested that

carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere could be controlled by planting fast-growing trees. He calculates that it would take a trillion trees to remove all carbon from the atmosphere.

[59][60]

In a 2014 interview, he said that "What I’m convinced of is that we don’t understand climate ... It will take a lot of very hard work before that question is settled."

[2]

Nuclear winter

From his 1988 book

Infinite in All Directions, he offered some criticism of then current models predicting a devastating

nuclear winter in the event of a large-scale nuclear war:

As a scientist I want to rip the theory of nuclear winter apart, but as a human being I want to believe it. This is one of the rare instances of a genuine conflict between the demands of science and the demands of humanity. As a scientist, I judge the nuclear winter theory to be a sloppy piece of work, full of gaps and unjustified assumptions. As a human being, I hope fervently that it is right. Here is a real and uncomfortable dilemma. What does a scientist do when science and humanity pull in opposite directions?[61]

Warfare and weapons

At the

British Bomber Command, Dyson and colleagues proposed ripping out two gun turrets from the RAF

Lancaster bombers, to cut the catastrophic losses due to German fighters in the

Battle of Berlin. A Lancaster without turrets could fly 50 mph (80 km/h) faster and be much more maneuverable.

All our advice to the commander in chief [went] through the chief of our section, who was a career civil servant. His guiding principle was to tell the commander in chief things that the commander in chief liked to hear… To push the idea of ripping out gun turrets, against the official mythology of the gallant gunner defending his crew mates…was not the kind of suggestion the commander in chief liked to hear.[62]

On hearing the news of the bombing of

Hiroshima:

I agreed emphatically with Henry Stimson. Once we had got ourselves into the business of bombing cities, we might as well do the job competently and get it over with. I felt better that morning than I had felt for years… Those fellows who had built the atomic bombs obviously knew their stuff… Later, much later, I would remember [the downside].[63]

I am convinced that to avoid nuclear war it is not sufficient to be afraid of it. It is necessary to be afraid, but it is equally necessary to understand. And the first step in understanding is to recognize that the problem of nuclear war is basically not technical but human and historical. If we are to avoid destruction we must first of all understand the human and historical context out of which destruction arises.[64]

In 1967, in his capacity as a military adviser Dyson wrote an influential paper on the issue of possible US use of tactical nuclear weapons in the

Vietnam War. When a general said in a meeting "I think it might be a good idea to throw in a nuke now and then, just to keep the other side guessing,"

[65] Dyson became alarmed and obtained permission to write an objective report discussing the pros and cons of using such weapons from a purely military point of view. (This report,

Tactical Nuclear Weapons in Southeast Asia, published by the

Institute for Defense Analyses, was obtained, with some redactions, by The

Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability under the

Freedom of Information act in 2002.)

[66] It was sufficiently objective that both sides in the debate based their arguments on it. Dyson says that the report showed that even from a narrow military point of view the US was better off not using nuclear weapons. Dyson stated on the

Dick Cavett show that the use of nuclear weaponry was a bad idea for the US at the time because "our targets were large and theirs were small." (His unstated assumption was that the Soviets would respond by supplying tactical nukes to the other side.)

Dyson opposed the

Vietnam War, the

Gulf War, and the

invasion of Iraq. He supported

Barack Obama in the

2008 US presidential election and

The New York Times has described him as a

political liberal.

[18]

Civil Defense

While teaching for a few weeks in Zurich, Dyson was visited by two officials from the Swiss civil defense authority. Their experts were telling them that fairly simple shelters on a large scale would enable them to survive a nuclear attack, and they wanted confirmation. They knew that Dyson had a security clearance. Dyson reassured them that their shelters would do the job. The US doesn't build such shelters because it would be contrary to the doctrine of

Mutual assured destruction and destabilize things, because the US would be able to launch a first strike and survive a retaliatory second strike.

[67]

The role of failure

You can't possibly get a good technology going without an enormous number of failures. It's a universal rule. If you look at bicycles, there were thousands of weird models built and tried before they found the one that really worked. You could never design a bicycle theoretically. Even now, after we've been building them for 100 years, it's very difficult to understand just why a bicycle works – it's even difficult to formulate it as a mathematical problem. But just by trial and error, we found out how to do it, and the error was essential.[68]

On English academics

My view of the prevalence of doom-and-gloom in Cambridge is that it is a result of the English class system. In England there were always two sharply opposed middle classes, the academic middle class and the commercial middle class. In the nineteenth century, the academic middle class won the battle for power and status. As a child of the academic middle class, I learned to look on the commercial middle class with loathing and contempt. Then came the triumph of Margaret Thatcher, which was also the revenge of the commercial middle class. The academics lost their power and prestige and the business people took over. The academics never forgave Thatcher and have been gloomy ever since.[69]

Science and religion

He is a

non-denominational Christian and has attended various churches from

Presbyterian to

Roman Catholic. Regarding doctrinal or

Christological issues, he has said, "I am neither a saint nor a theologian. To me, good works are more important than theology."

[70]

Science and religion are two windows that people look through, trying to understand the big universe outside, trying to understand why we are here. The two windows give different views, but they look out at the same universe. Both views are one-sided, neither is complete. Both leave out essential features of the real world. And both are worthy of respect.

Trouble arises when either science or religion claims universal jurisdiction, when either religious or scientific dogma claims to be infallible. Religious creationists and scientific materialists are equally dogmatic and insensitive. By their arrogance they bring both science and religion into disrepute. The media exaggerate their numbers and importance. The media rarely mention the fact that the great majority of religious people belong to moderate denominations that treat science with respect, or the fact that the great majority of scientists treat religion with respect so long as religion does not claim jurisdiction over scientific questions.[70]

Dyson partially disagrees with the famous remark by his fellow physicist

Steven Weinberg that "With or without religion, good people can behave well and bad people can do evil; but for good people to do evil—that takes religion."

[71]

Weinberg's statement is true as far as it goes, but it is not the whole truth. To make it the whole truth, we must add an additional clause: "And for bad people to do good things—that [also] takes religion." The main point of Christianity is that it is a religion for sinners. Jesus made that very clear. When the Pharisees asked his disciples, "Why eateth your Master with publicans and sinners?" he said, "I come to call not the righteous but sinners to repentance." Only a small fraction of sinners repent and do good things but only a small fraction of good people are led by their religion to do bad things.[71]

While Dyson has labeled himself a Christian, he identifies himself as agnostic about some of the specifics of his faith.

[72][73] For example, here is a passage from Dyson's review of

The God of Hope and the End of the World from

John Polkinghorne:

I am myself a Christian, a member of a community that preserves an ancient heritage of great literature and great music, provides help and counsel to young and old when they are in trouble, educates children in moral responsibility, and worships God in its own fashion. But I find Polkinghorne’s theology altogether too narrow for my taste. I have no use for a theology that claims to know the answers to deep questions but bases its arguments on the beliefs of a single tribe. I am a practicing Christian but not a believing Christian. To me, to worship God means to recognize that mind and intelligence are woven into the fabric of our universe in a way that altogether surpasses our comprehension.[74]

Works

- Symmetry Groups in Nuclear and Particle Physics, 1966 (Academic-oriented text)

- Interstellar Transport, Physics Today 1968

- Disturbing the Universe, 1979, ISBN 0-06-011108-9. [75] Review

- Weapons and Hope, 1984 (Winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award).[18][76] Review

- Origins of Life, 1986. Second edition, 1999. [77] Review

- Infinite in All Directions, 1988, ISBN 0-14-014482-X. Review

- From Eros to Gaia, 1992 [78]

- Selected Papers of Freeman Dyson, (Selected Works up to 1990) American Mathematical Society, 1996.

- Imagined Worlds, Harvard University Press 1997, ISBN 978-0-674-53908-2. [79] Review

- The Sun, the Genome and the Internet, 1999. [80] Review

- L'mportanza di essere imprevedibile, Di Renzo Editore, 2003

- The Scientist as Rebel, 2006. Review

- Advanced Quantum Mechanics, World Scientific, 2007, ISBN 978-981-270-661-4. [81] Freely available at: arXiv:quant-ph/0608140. (Dyson's 1951 Cornell lecture notes transcribed by David Derbes)

- A Many-Colored Glass: Reflections on the Place of Life in the Universe, University of Virginia Press, 2007. Review

- Birds and Frogs: Selected Papers, 1990-2014, World Scientific Publishing Company, 2015.

In popular culture

The fictional character

Gordon Freeman from the

Half Life series is named after Freeman Dyson.

an entity of basic importance in the

an entity of basic importance in the