From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Noam Chomsky | |

|---|---|

On a visit to Vancouver, British Columbia in 2004

|

|

| Born | December 7, 1928 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States |

| Other names | Avram Noam Chomsky |

| Alma mater | University of Pennsylvania (B.A.) 1949, (M.A.) 1951, (Ph.D.) 1955 |

| Era | 20th/21st-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Generative linguistics, Analytic philosophy |

| Institutions | MIT (1955–present) |

Main interests

|

Linguistics · Metalinguistics Psychology Philosophy of language Philosophy of mind Politics · Ethics |

| Website | |

| chomsky |

|

Avram Noam Chomsky (/ˈnoʊm ˈtʃɒmski/; born December 7, 1928) is an American linguist, philosopher,[21][22] cognitive scientist, logician,[23][24][25] political commentator, social justice activist, and anarcho-syndicalist advocate. Sometimes described as the "father of modern linguistics",[26][27] Chomsky is also a major figure in analytic philosophy.[21] He has spent most of his career at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he is currently Professor Emeritus, and has authored over 100 books. He has been described as a prominent cultural figure, and was voted the "world's top public intellectual" in a 2005 poll.[28]

Born to a middle-class Ashkenazi Jewish family in Philadelphia, Chomsky developed an early interest in anarchism from relatives in New York City. He later undertook studies in linguistics at the University of Pennsylvania, where he obtained his BA, MA, and PhD, while from 1951 to 1955 he was appointed to Harvard University's Society of Fellows. In 1955 he began work at MIT, soon becoming a significant figure in the field of linguistics for his publications and lectures on the subject. He is credited as the creator or co-creator of the Chomsky hierarchy, the universal grammar theory, the Chomsky–Schützenberger representation theorem, and the Chomsky–Schützenberger enumeration theorem. Chomsky also played a major role in the decline of behaviorism, and was especially critical of the work of B.F. Skinner.[29][30] In 1967 he gained public attention for his vocal opposition to U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War, in part through his essay The Responsibility of Intellectuals, and came to be associated with the New Left while being arrested on multiple occasions for his anti-war activism. While expanding his work in linguistics over subsequent decades, he also developed the propaganda model of media criticism with Edward S. Herman. Following his retirement from active teaching, he has continued his vocal public activism, for instance supporting the anti-Iraq War and Occupy movements.

Chomsky has been a highly influential academic figure throughout his career, and was cited within the field of Arts and Humanities more often than any other living scholar between 1980 and 1992. He was also the eighth most cited scholar overall within the Arts and Humanities Citation Index during the same period.[31][32][33][34] His work has influenced fields such as artificial intelligence, cognitive science, computer science, logic, mathematics, music theory and analysis, political science, programming language theory and psychology.[33][34][35][36][37] Chomsky continues to be well known as a political activist, and a leading critic of U.S. foreign policy, neoliberal capitalism, and the mainstream news media. Ideologically, he aligns himself with anarcho-syndicalism and libertarian socialism.[38]

Early life

Childhood: 1928–45

Avram Noam Chomsky was born on December 7, 1928, in the affluent East Oak Lane neighborhood of Philadelphia.[39] His father was the Ukrainian-born William "Zev" Chomsky, who had fled to the United States in 1913 and his mother was the Lithuanian-born Elsie Simonofsky.[40] Both of his parents were Ashkenazi Lithuanian Jews. Having studied at Johns Hopkins University, his father went on to become school principal of the Congregation Mikveh Israel religious school, and in 1924 was appointed to the faculty at Gratz College in Philadelphia. Independently, William researched Medieval Hebrew, and would publish a series of books on the subject. William's wife, Elsie, was born in Belarus. They met at Mikveh Israel, where both taught Hebrew language classes.[41] Described as a "very warm, gentle, and engaging" individual, William placed a great emphasis on educating people so that they would be "well integrated, free and independent in their thinking, and eager to participate in making life more meaningful and worthwhile for all", a view subsequently adopted by his son.[42]

"What motivated his [political] interests? A powerful curiosity, exposure to divergent opinions, and an unorthodox education have all been given as answers to this question. He was clearly struck by the obvious contradictions between his own readings and mainstream press reports. The measurement of the distance between the realities presented by these two sources, and the evaluation of why such a gap exists, remained a passion for Chomsky."

Biographer Robert F. Barsky, 1997.[43]

Noam described his parents as "normal Roosevelt Democrats", having a centre-left position on the political spectrum, but he was exposed to far left politics through other members of the family, a number of whom were socialists involved in the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union.[48] He was influenced largely by his uncle who owned a newspaper stand in New York City where Jewish leftists came to debate the issues of the day.[47][49]

Whenever visiting his relatives in New York City, Chomsky frequented left-wing and anarchist bookstores, voraciously reading political literature.[47][49] He later described his discovery of anarchism as a "lucky accident", allowing him to become critical of other radical left-wing ideologies, namely Marxism-Leninism.[50] Chomsky's primary education was at Oak Lane Country Day School, an independent institution that focused on allowing its pupils to pursue their own interests in a non-competitive atmosphere. It was here that he wrote his first article, aged 10, on the spread of fascism, following the fall of Barcelona in the Spanish Civil War. From the age of 12 or 13, he identified more fully with anarchist politics.[51][52] Aged 12, he moved on to secondary education at Central High School, where he joined various clubs and societies but was troubled by the hierarchical and regimented method of teaching that they employed.[53]

University: 1945–55

Anarcho-syndicalist Rudolf Rocker (left) and English democratic socialist George Orwell (right) were both influences on the young Chomsky.

Aged 16, in 1945 Chomsky embarked on a general program of study at the University of Pennsylvania, where his primary interest was in learning Arabic. Living at home, he funded his undergraduate degree by teaching Hebrew.[54] Although dissatisfied with the university's strict structure, he was encouraged to continue by the Russian-born linguist Zellig Harris, who convinced Chomsky to major in the subject.[55] Chomsky's BA honor's thesis was titled "Morphophonemics of Modern Hebrew", and revised it for his MA thesis, which he attained at Penn in 1951; it would subsequently be published as a book.[56][57] From 1951 to 1955 he was named to the Society of Fellows at Harvard University while undertaking his doctoral research.[58] Being highly critical of the established behaviourist currents in linguistics, in 1954 he presented his ideas at lectures given at the University of Chicago and Yale University.[59] In 1955 he was awarded his PhD from the University of Pennsylvania for a thesis setting out his ideas on transformational grammar; it would be published in 1975 as The Logical Structure of Linguistic Theory.[60]

In 1947, Chomsky entered into a romantic relationship with Carol Doris Schatz, whom he had known since they were toddlers. They were married in 1949,[61] and remained together until her death in 2008.[62] They considered moving to Israel, and in 1953 spent six weeks at the HaZore'a kibbutz; although enjoying himself, Chomsky was appalled by the Jewish nationalism and anti-Arab racism he encountered in the country, and the pro-Stalinist trend that he thought pervaded the kibbutz's leftist community.[63]

On visits to New York City, Chomsky frequented the office of Yiddish anarchist journal Freie Arbeiter Stimme, becoming enamored with the work of contributor Rudolf Rocker, whose work introduced him to the link between anarchism and classical liberalism.[64] Other political thinkers whose work Chomsky read included the anarchist Diego Abad de Santillán, democratic socialists George Orwell, Bertrand Russell, and Dwight Macdonald, and works by Marxists Karl Liebknecht, Karl Korsch, and Rosa Luxemburg.[65] His readings convinced him of the desirability of an anarcho-syndicalist society, and he became fascinated by the anarcho-syndicalist communes set up during the Spanish Civil War documented in Orwell's Homage to Catalonia (1938).[66] He avidly read leftist journal Politics, remarking that it "answered to and developed" his interest in anarchism,[67] as well as the periodical Living Marxism, published by council communist Paul Mattick. Although rejecting its Marxist basis, Chomsky was heavily influenced by council communism, voraciously reading articles in Living Marxism written by Antonie Pannekoek.[68] He was greatly interested in the Marlenite ideas of the Leninist League, an anti-Stalinist Marxist-Leninist group, sharing their views that the Second World War was orchestrated by Western capitalists and the Soviet Union's "state capitalists" to crush Europe's proletariat.[69]

Early career: 1955–1966

In 1955, Chomsky obtained a job as an assistant professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), spending half his time on a mechanical translation project and the other half teaching linguistics and philosophy.[70] He later described MIT as "a pretty free and open place, open to experimentation and without rigid requirements. It was just perfect for someone of my idiosyncratic interests and work."[71] In 1957 MIT promoted him to the position of associate professor, while from 1957–58 he was also employed by New York City's Columbia University as a visiting professor.[72] That same year, the Chomskys' first child was born,[73] and he published his first work on linguistics, Syntactic Structures, a book that radically opposed the dominant Harris-Bloomfield trend in the field. The response to Chomsky's ideas ranged from indifference to hostility, and his work proved divisive and caused"significant upheaval" in the discipline.[74] Linguist John Lyons later asserted that it "revolutionized the scientific study of language."[75] From 1958–59 Chomsky was a National Science Foundation fellow at Princeton University's Institute for Advanced Study.[76]

In 1959 he attracted further attention for his review of B.F. Skinner's 1957 book Verbal Behavior in the journal Language,[77] in which he argued that Skinner ignored the role of human creativity in linguistics.[78] Becoming an "established intellectual",[79] with his colleague Morris Halle, he founded the MIT's Graduate Program in linguistics, and in 1961 he was made professor of foreign language and linguistics, thereby gaining academic tenure.[80] He was appointed plenary speaker at the Ninth International Congress of Linguists, held in 1962 at Cambridge, Massachusetts; the event established him as the de facto spokesperson of American linguistics.[81] He continued to publish his linguistic ideas throughout the decade, as Aspects of the Theory of Syntax (1966), Topics in the Theory of Generative Grammar (1966), and Cartesian Linguistics: A Chapter in the History of Linguistic Thought (1966).[82] Along with Halle, he also edited the Studies in Language Series of books for Harper and Row.[83] He continued to receive academic recognition and honors for his work, in 1966 visiting a variety of Californian institutions, first as the Linguistics Society of America Professor at the University of California, and then as the Beckman Professor at the University of California, Berkeley.[84] His Beckman lectures would be assembled and published as Language and Mind in 1968.[85]

Rise to prominence

Anti-Vietnam War activism: 1967–1975

1967 marked Chomsky's entry into the public debate on the United States' foreign policy.[87] In February he published an influential essay in The New York Review of Books titled The Responsibility of Intellectuals, in which he criticized the country's involvement in the Vietnam War.[85][88] He expanded on his argument to produce his first political book, American Power and the New Mandarins, which was published in 1969 and soon established him at the forefront of American dissent.[89] In 1971 he gave the Bertrand Russell Memorial Lectures in Cambridge, which were published as Problems of Knowledge and Freedom later that year, while other political books at the time included At War with Asia (1970) and For Reasons of State (1973).[90] Coming to be associated with the American New Left movement,[91] he nevertheless thought little of prominent New Left intellectuals Herbert Marcuse and Erich Fromm, and preferred the company of activists to intellectuals.[92] Although he had initially arisen to attention for his political views in The New York Review of Books, throughout the late 1960s and early 1970s, he was virtually ignored by the mainstream press.[93]Along with his writings, Chomsky also became actively involved in left-wing activism. Refusing to pay half his taxes, in 1967 he publicly supported students who refused the draft, and was arrested for being part of an anti-war teach-in outside the Pentagon.[94] During this time Chomsky founded the anti-war collective RESIST along with Mitchell Goodman, Denise Levertov, William Sloane Coffin, and Dwight Macdonald.[94] Supporting the student protest movement, he gave many lectures to student activist groups, though questioned the objectives of the 1968 student protests.[95] Along with colleague Louis Kampf, he also began running undergraduate courses on politics at MIT, independent of the conservative-dominated political science department.[96] His public talks often generated considerable controversy, particularly when he criticized actions of the Israeli government and military.[97] His political views came under attack from right-wing and centrist figures, the most prominent of whom was Alan Dershowitz; Chomsky considered Dershowitz "a complete liar" and accused him of actively misrepresenting his position on issues.[98] As a result of his anti-war activism, Chomsky was arrested on multiple occasions, and U.S.

President Richard Nixon included him on his Enemies' List.[99] He was aware of the potential repercussions of his activism, and so his wife began training to become an academic in order to support the family in the event of Chomsky's unemployment or imprisonment.[100]

Although under some pressure to do so, MIT refused to fire him due to his influential standing in the field of linguistics.[101] His work in this area continued to gain international recognition: in 1967 the University of London awarded him an honorary D. Litt while the University of Chicago gave him an honorary D.H.L.[102] In 1970, Loyola University and Swarthmore College also awarded him honorary D.H.L.'s, as did Bard College in 1971, Delhi University in 1972, and the University of Massachusetts in 1973.[103] In 1974 he became a corresponding fellow of the British Academy.[104] Chomsky continued to write on the subject, publishing Studies on Semantics in Generative Grammar (1972).[101] In 1971 he carried out a televised interview with French philosopher Michel Foucault on Dutch television; he largely agreed with Foucault's ideas, but was critical of post-modernism and French philosophy generally, lambasting France as having "a highly parochial and remarkably illiterate culture."[105]

Work on the media: 1976–1989

Throughout the late 1970s and 1980s, Chomsky's publications expanded and clarified his earlier work, addressing his critics and updating his grammatical theory.[106]

In 1979, Chomsky and Herman published the two-volume The Political Economy of Human Rights, in which they compared U.S. media reactions to the Cambodian genocide and the Indonesian occupation of East Timor. They argued that because Indonesia was a U.S. ally, U.S. media ignored the East Timorian situation while focusing on that in Cambodia, a U.S. enemy.[107] The following year, Steven Lukas authored an article for the Times Higher Education Supplement accusing Chomsky of betraying his anarchist ideals and acting as an apologist for Cambodian leader Pol Pot. Although Laura J. Summers and Robin Woodsworth Carlsen replied to the article, arguing that Lukas completely misunderstood Chomsky and Herman's work, Chomsky himself did not. The controversy damaged his reputation.[108] Chomsky maintained that his critics printed lies about him to discredit his reputation.[109]

Although Chomsky had long publicly criticised Nazism and totalitarianism more generally, his commitment to freedom of speech led him to defend the right of French historian Robert Faurisson to advocate a position widely characterised as Holocaust denial. Chomsky's plea for the historian's freedom of speech would be published as the preface to Faurisson's 1980 book Mémoire en défense contre ceux qui m'accusent de falsifier l'histoire.[110]

Chomsky was widely condemned for defending Faurisson.[111] France's mainstream press accused Chomsky of being a Holocaust denier himself, and refused to publish his rebuttals to their accusations.[112] The Faurrison Affair had a lasting, damaging effect on Chomsky's career;[111] Werner Cohn's Partners in Hate: Noam Chomsky and the Holocaust Deniers contained numerous falsified claims.[113]

Increased political activism: 1990–present

In the 1990s, Chomsky embraced political activism to a greater degree than before.[114]His far-reaching criticisms of U.S. foreign policy and the legitimacy of U.S. power have raised controversy.[115][116] Chomsky has received death threats because of his criticisms of U.S. foreign policy.[117] He has often received undercover police protection at MIT and when speaking on the Middle East, although he has refused uniformed police protection.[118] The Electronic Intifada website claims that the Anti-Defamation League "spied on" Chomsky's appearances, and quotes Chomsky as being unsurprised at that discovery or the use of what Chomsky claims is "fantasy material" provided to Alan Dershowitz for debating him. Amused, Chomsky compares the ADL's reports to FBI files.[119]

Chomsky resides in Lexington, Massachusetts, and travels, giving lectures on politics and linguistics.

Linguistic theory

The basis to Chomsky's linguistic theory is that the principles underlying the structure of language are biologically determined in the human mind and hence genetically transmitted.[120] He therefore argues that all humans share the same underlying linguistic structure, irrespective of socio-cultural difference.[121] In this he opposes the radical behaviourist psychology of B.F. Skinner, instead arguing that human language is unlike modes of communication used by any other animal species.[122]Chomskyan linguistics, beginning with his Syntactic Structures, a distillation of his Logical Structure of Linguistic Theory (1955, 75), challenges structural linguistics and introduces transformational grammar.[123] This approach takes utterances (sequences of words) to have a syntax characterized by a formal grammar; in particular, a context-free grammar extended with transformational rules.

Perhaps his most influential and time-tested contribution to the field is the claim that modeling knowledge of language using a formal grammar accounts for the "productivity" or "creativity" of language. In other words, a formal grammar of a language can explain the ability of a hearer-speaker to produce and interpret an infinite number of utterances, including novel ones, with a limited set of grammatical rules and a finite set of terms. He has always acknowledged his debt to Pāṇini for his modern notion of an explicit generative grammar, although it is also related to Cartesian approach[124] and rationalist ideas of a priori knowledge.

Chomsky has argued that linguistic structures are at least partly innate, and that they reflect a "universal grammar" (UG) that underlies and can account for all human grammatical systems (in general known as mentalism).[125]

Chomsky based his argument on observations about human language acquisition. For example, while a human baby and a kitten are both capable of inductive reasoning, if they are exposed to exactly the same linguistic data, the human will always acquire the ability to understand and produce language, while the kitten will never acquire either ability. Chomsky labeled whatever the relevant capacity the human has that the cat lacks as the language acquisition device (LAD), and he suggested that one of the tasks for linguistics should be to determine what the LAD is and what constraints it imposes on the range of possible human languages. The universal features that would result from these constraints are often termed "universal grammar" or UG.[126][127]

Chomsky's ideas have had a strong influence on researchers of language acquisition in children, though many researchers in this area such as Elizabeth Bates[128] and Michael Tomasello[129] argue very strongly against Chomsky's theories, and instead advocate emergentist or connectionist theories, explaining language with a number of general processing mechanisms in the brain that interact with the extensive and complex social environment in which language is used and learned.

Generative grammar

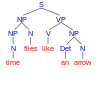

|

|

|

|

Chomsky's theories have been immensely influential within linguistics, but they have also received criticism. One recurring criticism of the Chomskyan variety of generative grammar is that it is Anglocentric and Eurocentric, and that often linguists working in this tradition have a tendency to base claims about Universal Grammar on a very small sample of languages, sometimes just one. Initially, the Eurocentrism was exhibited in an overemphasis on the study of English. However, hundreds of different languages have now received at least some attention within Chomskyan linguistic analyses.[131][132][133][134][135] In spite of the diversity of languages that have been characterized by UG derivations, critics continue to argue that the formalisms within Chomskyan linguistics are Anglocentric and misrepresent the properties of languages that are structurally different from English.[136][137][138]

Thus, Chomsky's approach has been criticized as a form of linguistic imperialism.[139] In addition, Chomskyan linguists rely heavily on the intuitions of native speakers regarding which sentences of their languages are well-formed. This practice has been criticized on general methodological grounds. Some psychologists and psycholinguists,[who?] though sympathetic to Chomsky's overall program, have argued that Chomskyan linguists pay insufficient attention to experimental data from language processing, with the consequence that their theories are not psychologically plausible. Other critics (see language learning) have questioned whether it is necessary to posit Universal Grammar to explain child language acquisition, arguing that domain-general learning mechanisms are sufficient.

Today there are many different branches of generative grammar. One can view grammatical frameworks such as head-driven phrase structure grammar, lexical functional grammar, and combinatory categorial grammar as broadly Chomskyan and generative in orientation, but with significant differences in execution.

Chomsky hierarchy

Chomsky is famous for investigating various kinds of formal languages and whether or not they might be capable of capturing key properties of human language. His Chomsky hierarchy partitions formal grammars into classes/types,[140] or groups, with increasing expressive power, i.e., each successive class can generate a broader set of formal languages than the one before. Interestingly, Chomsky argues that modeling some aspects of human language requires a more complex formal grammar (as measured by the Chomsky hierarchy) than modeling others.

For example, while a regular language is powerful enough to model English morphology, it is not powerful enough to model English syntax. In addition to being relevant in linguistics, the Chomsky hierarchy has also become important in computer science (especially in programming language,[141] compiler construction, and automata theory).[142] Indeed, there is an equivalence between the Chomsky language hierarchy and the different kinds of automata. Thus theorems about languages are often dealt with as either languages (grammars) or automata.

Chomsky refuses to take legal action against those who may have libeled him and prefers to counter libels through open letters in newspapers. One example of this approach is his response to an article by Emma Brockes in The Guardian at the end of October 2005, which alleged that he had denied the Srebrenica massacre in 1995.[165][166][167] At issue was Chomsky's attitude to the writings of journalist Diana Johnstone on the subject.[168] His complaint prompted The Guardian to publish an apologetic correction and to withdraw the article from the paper's website,[169] which remains available on his own website.[170] Nick Cohen has criticised Chomsky for frequently making overly critical statements about Western governments, especially the US, and for allegedly refusing to retract his speculations when facts become available that disprove them.[171]

Chomsky is known for his "dry, laconic wit", although he has attracted controversy for labeling established political and academic figures with terms like "corrupt", "fascist", and "fraudulent".[196] When asked if he is an atheist, Chomsky replied, "What is it that I'm supposed to not believe in? Until you can answer that question I can't tell you whether I'm an atheist."[197]

Chomsky was married to Carol Doris Schatz (Chomsky) from 1949 until her death in 2008. They had three children together: Aviva, Diane and Harry.[198] In 2014, Chomsky remarried to Valeria Wasserman.[199]

Chomsky's work in linguistics has had implications for modern psychology.[36] Nim Chimpsky, a chimpanzee who was the subject of a study in animal language acquisition at Columbia University, was named after Chomsky in reference to his view of language acquisition as a uniquely human ability.[citation needed] The 1984 Nobel Prize laureate in Medicine and Physiology, Niels Kaj Jerne, used Chomsky's generative model to explain the human immune system, equating "components of a generative grammar … with various features of protein structures". The title of Jerne's Stockholm Nobel Lecture was "The Generative Grammar of the Immune System".[204] Computer scientist Donald Knuth read Syntactic Structures during his honeymoon and was influenced by it. "I must admit to taking a copy of Noam Chomsky's Syntactic Structures along with me on my honeymoon in 1961 ... Here was a marvelous thing: a mathematical theory of language in which I could use a computer programmer's intuition!"[205]

Chomsky has received many honorary degrees from universities around the world, including from the following:

He is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the National Academy of Sciences, and the American Philosophical Society. In addition, he is a member of other professional and learned societies in the United States and abroad, and is a recipient of the Distinguished Scientific Contribution Award of the American Psychological Association, the Kyoto Prize in Basic Sciences, the Helmholtz Medal, the Dorothy Eldridge Peacemaker Award, the 1999 Benjamin Franklin Medal in Computer and Cognitive Science, and others.[212] He is twice winner of The Orwell Award, granted by The National Council of Teachers of English for "Distinguished Contributions to Honesty and Clarity in Public Language" (in 1987 and 1989).[213]

He is a member of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts in Department of Social Sciences.[214]

In 2004 Chomsky received the Carl-von-Ossietzky Prize from the city of Oldenburg (Germany) for his life work as political analyst and media critic.[215] In 2005, Chomsky received an honorary fellowship from the Literary and Historical Society.[216] In 2007, Chomsky received The Uppsala University (Sweden) Honorary Doctor's degree in commemoration of Carolus Linnaeus.[217] In February 2008, he received the President's Medal from the Literary and Debating Society of the National University of Ireland, Galway.[218] Since 2009 he is an honorary member of IAPTI.[219]

In 2010, Chomsky received the Erich Fromm Prize in Stuttgart, Germany.[220] In April 2010, Chomsky became the third scholar to receive the University of Wisconsin's A.E. Havens Center's Award for Lifetime Contribution to Critical Scholarship.[221]

Chomsky has an Erdős number of four.[222]

Chomsky was voted the leading living public intellectual in The 2005 Global Intellectuals Poll conducted by the British magazine Prospect. He reacted, saying "I don't pay a lot of attention to polls".[223] In a list compiled by the magazine New Statesman in 2006, he was voted seventh in the list of "Heroes of our time".[224]

Actor Viggo Mortensen with avant-garde guitarist Buckethead dedicated their 2006 album, called Pandemoniumfromamerica, to Chomsky.[225]

On January 22, 2010, a special honorary concert for Chomsky was given at Kresge Auditorium at MIT.[226][227] The concert, attended by Chomsky and dozens of his family and friends, featured music composed by Edward Manukyan and speeches by Chomsky's colleagues, including David Pesetsky of MIT and Gennaro Chierchia, head of the linguistics department at Harvard University.

In June 2011, Chomsky was awarded the Sydney Peace Prize, which cited his "...unfailing courage, critical analysis of power and promotion of human rights."[228]

In 2011, Chomsky was inducted into IEEE Intelligent Systems' AI's Hall of Fame for the "significant contributions to the field of AI and intelligent systems".[229][230]

In 2013, a newly described species of bee was named after him: Megachile chomskyi.[231]

Political views

Chomsky's political views have changed little since his childhood.[143] His ideological position revolves around "nourishing the libertarian and creative character of the human being",[143] and he has described his beliefs as "fairly traditional anarchist ones, with origins in the Enlightenment and classical liberalism."[144] He has praised libertarian socialism,[145] and has described himself as an anarcho-syndicalist.[146] He is a member of the Campaign for Peace and Democracy and the Industrial Workers of the World international union.[147] Chomsky is also a member of the interim consultative committee of the International Organization for a Participatory Society, which he describes as having the potential to "...carry us a long way towards unifying the many initiatives here and around the world and molding them into a powerful and effective force."[148][149] He advocates popular struggle for greater democracy.[150] He has stated his opposition to ruling elites, among them institutions like the IMF, World Bank, and GATT.[151]Authority

Chomsky asserts that authority, unless justified, is inherently illegitimate, and that the burden of proof is on those in authority. If this burden can't be met, the authority in question should be dismantled. Authority for its own sake is inherently unjustified. An example given by Chomsky of a legitimate authority is that exerted by an adult to prevent a young child from wandering into traffic.[152] He contends that there is little moral difference between chattel slavery and renting one's self to an owner or "wage slavery". He feels that it is an attack on personal integrity that undermines individual freedom. He holds that workers should own and control their workplace.[153]Capitalism and socialism

Chomsky is critical of both the American state capitalist system[155] and the authoritarian branches of socialism. He argues that libertarian socialist values are the proper extension of classical liberalism to an advanced industrial context,[156] and that society should be highly organized and based on democratic control of communities and work places. He views the radical humanist ideas of his two major influences, Bertrand Russell and John Dewey, as "rooted in the Enlightenment and classical liberalism, while retaining their revolutionary character."[157]United States foreign policy

Chomsky has strongly criticized the foreign policy of the United States. He claims double standards in a foreign policy preaching democracy and freedom for all while allying itself with non-democratic and repressive states and organizations such as Chile under Augusto Pinochet and argues that this results in massive human rights violations. He often argues that America's intervention in foreign nations — including secret aid the U.S. gave to the Contras in Nicaragua, an event he has been critical of — fits any standard description of terrorism,[158] including "official definitions in the US Code and Army Manuals in the early 1980s."[159][160] Before its collapse, Chomsky also condemned Soviet imperialism; for example in 1986 during a question–answer session following a lecture he gave at Universidad Centroamericana in Nicaragua, when challenged about how he could "talk about North American imperialism and Russian imperialism in the same breath," Chomsky responded: "One of the truths about the world is that there are two superpowers, one a huge power which happens to have its boot on your neck; another, a smaller power which happens to have its boot on other people's necks. I think that anyone in the Third World would be making a grave error if they succumbed to illusions about these matters."[161] Martha Nussbaum criticizes Chomsky for failing to condemn atrocities by leftist insurgents because "for some leftists … one should not criticize one's friends, that solidarity is more important than ethical correctness."[162]Free speech

Chomsky has a broad view of free-speech rights, especially in the mass media, and opposes censorship. He has stated that "with regard to freedom of speech there are basically two positions: you defend it vigorously for views you hate, or you reject it and prefer Stalinist/fascist standards".[163] With reference to the United States diplomatic cables leak, Chomsky suggested that "perhaps the most dramatic revelation … is the bitter hatred of democracy that is revealed both by the U.S. Government – Hillary Clinton, others – and also by the diplomatic service."[164]Chomsky refuses to take legal action against those who may have libeled him and prefers to counter libels through open letters in newspapers. One example of this approach is his response to an article by Emma Brockes in The Guardian at the end of October 2005, which alleged that he had denied the Srebrenica massacre in 1995.[165][166][167] At issue was Chomsky's attitude to the writings of journalist Diana Johnstone on the subject.[168] His complaint prompted The Guardian to publish an apologetic correction and to withdraw the article from the paper's website,[169] which remains available on his own website.[170] Nick Cohen has criticised Chomsky for frequently making overly critical statements about Western governments, especially the US, and for allegedly refusing to retract his speculations when facts become available that disprove them.[171]

Debates

Chomsky has been known to defend vigorously and debate his views and opinions, in philosophy, linguistics (Linguistics Wars), and politics.[21] He has had notable debates with Jean Piaget,[172] Michel Foucault,[173] William F. Buckley, Jr.,[174] Christopher Hitchens,[175][176][177][178][179] George Lakoff,[180] Richard Perle,[181] Hilary Putnam,[182] Willard Van Orman Quine,[183][184] John Maynard Smith,[185] and Alan Dershowitz,[186] to name a few. The Guardian said of Chomsky's debating ability, "His boldness and clarity infuriates opponents—academe is crowded with critics who have made twerps of themselves taking him on."[187][188] In response to his speaking style being criticized as boring, Chomsky said, "I'm a boring speaker and I like it that way. ... I doubt that people are attracted to whatever the persona is. ... People are interested in the issues, and they're interested in the issues because they are important."[189] "We don't want to be swayed by superficial eloquence, by emotion and so on."[190]Personal life

Chomsky endeavors to keep his family life strictly separate from his political activism and career,[191] and considers himself "scrupulous at keeping my politics out of the classroom."[192] He is uninterested in appearances and the fame that his work has brought him.[193] He also has little interest in modern art and music.[194] He has been banned from entering Israel since 2010.[195]Chomsky is known for his "dry, laconic wit", although he has attracted controversy for labeling established political and academic figures with terms like "corrupt", "fascist", and "fraudulent".[196] When asked if he is an atheist, Chomsky replied, "What is it that I'm supposed to not believe in? Until you can answer that question I can't tell you whether I'm an atheist."[197]

Chomsky was married to Carol Doris Schatz (Chomsky) from 1949 until her death in 2008. They had three children together: Aviva, Diane and Harry.[198] In 2014, Chomsky remarried to Valeria Wasserman.[199]

Influence

Chomsky's legacy is as both a "leader in the field" of linguistics and "a figure of enlightenment and inspiration" for political dissenters.[200] Linguist John Lyons remarked that within a few decades of publication, Chomskyan linguistics had become "the most dynamic and influential" school of thought in the field.[201] Chomskyan models have been used as a theoretical basis in various fields of study. The Chomsky hierarchy is often taught in fundamental computer science courses as it confers insight into the various types of formal languages. This hierarchy can also be discussed in mathematical terms[202] and has generated interest among mathematicians, particularly combinatorialists. Some arguments in evolutionary psychology are derived from his research results.[203]Chomsky's work in linguistics has had implications for modern psychology.[36] Nim Chimpsky, a chimpanzee who was the subject of a study in animal language acquisition at Columbia University, was named after Chomsky in reference to his view of language acquisition as a uniquely human ability.[citation needed] The 1984 Nobel Prize laureate in Medicine and Physiology, Niels Kaj Jerne, used Chomsky's generative model to explain the human immune system, equating "components of a generative grammar … with various features of protein structures". The title of Jerne's Stockholm Nobel Lecture was "The Generative Grammar of the Immune System".[204] Computer scientist Donald Knuth read Syntactic Structures during his honeymoon and was influenced by it. "I must admit to taking a copy of Noam Chomsky's Syntactic Structures along with me on my honeymoon in 1961 ... Here was a marvelous thing: a mathematical theory of language in which I could use a computer programmer's intuition!"[205]

Academic achievements, awards, and honors

In early 1969, he delivered the John Locke Lectures at Oxford University; in January 1970, the Bertrand Russell Memorial Lecture at University of Cambridge; in 1972, the Nehru Memorial Lecture in New Delhi; in 1977, the Huizinga Lecture in Leiden; in 1988 the Massey Lectures at the University of Toronto, titled "Necessary Illusions: Thought Control in Democratic Societies"; in 1997, The Davie Memorial Lecture on Academic Freedom in Cape Town,[206] in 2011, the Rickman Godlee Lecture at University College, London[207] many others.[208]Chomsky has received many honorary degrees from universities around the world, including from the following:

- Amherst College

- Bard College

- Central Connecticut State University

- Columbia University

- Georgetown University

- Harvard University

- Islamic University of Gaza

- Loyola University Chicago

- McGill University

- National and Kapodistrian University of Athens

- National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM)

- National Tsing Hua University[209]

- National University of Colombia

- Peking University[210]

- Rovira i Virgili University

- Santo Domingo Institute of Technology

- Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa

- Swarthmore College

- University of Bologna

- University of Buenos Aires

- University of Calcutta

- University of Cambridge

- University of Chicago

- University of Chile

- University of Colorado[211]

- University of Connecticut

- University of Cyprus

- University of Delhi

- University of La Frontera

- University of London

- University of Maine

- University of Massachusetts Amherst

- University of Pennsylvania

- University of St. Andrews

- University of Toronto

- University of Western Ontario

- Uppsala University

- Villanova University

- Vrije Universiteit Brussel

He is a member of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts in Department of Social Sciences.[214]

In 2004 Chomsky received the Carl-von-Ossietzky Prize from the city of Oldenburg (Germany) for his life work as political analyst and media critic.[215] In 2005, Chomsky received an honorary fellowship from the Literary and Historical Society.[216] In 2007, Chomsky received The Uppsala University (Sweden) Honorary Doctor's degree in commemoration of Carolus Linnaeus.[217] In February 2008, he received the President's Medal from the Literary and Debating Society of the National University of Ireland, Galway.[218] Since 2009 he is an honorary member of IAPTI.[219]

In 2010, Chomsky received the Erich Fromm Prize in Stuttgart, Germany.[220] In April 2010, Chomsky became the third scholar to receive the University of Wisconsin's A.E. Havens Center's Award for Lifetime Contribution to Critical Scholarship.[221]

Chomsky was voted the leading living public intellectual in The 2005 Global Intellectuals Poll conducted by the British magazine Prospect. He reacted, saying "I don't pay a lot of attention to polls".[223] In a list compiled by the magazine New Statesman in 2006, he was voted seventh in the list of "Heroes of our time".[224]

Actor Viggo Mortensen with avant-garde guitarist Buckethead dedicated their 2006 album, called Pandemoniumfromamerica, to Chomsky.[225]

On January 22, 2010, a special honorary concert for Chomsky was given at Kresge Auditorium at MIT.[226][227] The concert, attended by Chomsky and dozens of his family and friends, featured music composed by Edward Manukyan and speeches by Chomsky's colleagues, including David Pesetsky of MIT and Gennaro Chierchia, head of the linguistics department at Harvard University.

In June 2011, Chomsky was awarded the Sydney Peace Prize, which cited his "...unfailing courage, critical analysis of power and promotion of human rights."[228]

In 2011, Chomsky was inducted into IEEE Intelligent Systems' AI's Hall of Fame for the "significant contributions to the field of AI and intelligent systems".[229][230]

In 2013, a newly described species of bee was named after him: Megachile chomskyi.[231]

Bibliography

Filmography

- Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media, Director: Mark Achbar and Peter Wintonick (1992)

- Last Party 2000, Director: Rebecca Chaiklin and Donovan Leitch (2001)

- Power and Terror: Noam Chomsky in Our Times, Director: John Junkerman (2002)

- Distorted Morality – America's War On Terror?, Director: John Junkerman (2003)

- Noam Chomsky: Rebel Without a Pause (TV), Director: Will Pascoe (2003)

- The Corporation, Directors: Mark Achbar and Jennifer Abbott; Writer: Joel Bakan (2003)

- Peace, Propaganda & the Promised Land, Directors: Sut Jhally and Bathsheba Ratzkoff (2004)

- On Power, Dissent and Racism: A discussion with Noam Chomsky, Journalist: Nicolas Rossier; Producers: Eli Choukri, Baraka Productions (2004)

- Chomsky was interviewed in the BBC documentary film The Power of Nightmares (2004)

- Lake of Fire, Director: Tony Kaye (2006)

- American Feud: A History of Conservatives and Liberals, Director: Richard Hall (2008)

- Chomsky & Cie, Director: Olivier Azam (out in 2008)

- An Inconvenient Tax, Director: Christopher P. Marshall (out in 2009)

- The Money Fix, Director: Alan Rosenblith (2009)

- Pax Americana and the Weaponization of Space, Director: Denis Delestrac (2010)

- Article 12: Waking up in a surveillance society, Director: Juan Manuel Biaiñ (2010)

- In 2012, Chomsky performed a deadpan cameo role in "MIT Gangnam Style", a parody of the "Gangnam Style" music video.[232] Also known informally as "Chomsky Style";[233] the video was described as the "Best Gangnam Style Parody Yet" by The Huffington Post[233] and it became a multi-million viewed "most popular" video on YouTube in its own right. (video link)[234]

- Chomsky was interviewed in Scott Noble's documentary film The Power Principle (2012)

- Is the Man Who Is Tall Happy?, Director: Michel Gondry (2013)

- We Are Many, Director: Amir Amirani (2014)

- Chomsky was interviewed in Boris Malagurski's documentary film The Weight of Chains 2 (2014)