From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

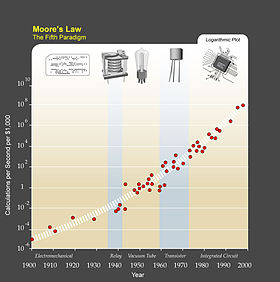

Moore's law is an example of futures studies; it is a statistical collection of past and present trends with the goal of accurately extrapolating future trends.

Futures studies (also called futurology) is the study of postulating possible, probable, and preferable futures and the worldviews and myths that underlie them. There is a debate as to whether this discipline is an art or science. In general, it can be considered as a branch of the social sciences and parallel to the field of history. History studies the past, futures studies considers the future. Futures studies (colloquially called "futures" by many of the field's practitioners) seeks to understand what is likely to continue and what could plausibly change. Part of the discipline thus seeks a systematic and pattern-based understanding of past and present, and to determine the likelihood of future events and trends.[1] Unlike the physical sciences where a narrower, more specified system is studied, futures studies concerns a much bigger and more complex world system. The methodology and knowledge are much less proven as compared to natural science or even social science like sociology, economics, and political science.

Overview

Futures studies is an interdisciplinary field, studying yesterday's and today's changes, and aggregating and analyzing both lay and professional strategies and opinions with respect to tomorrow. It includes analyzing the sources, patterns, and causes of change and stability in an attempt to develop foresight and to map possible futures. Around the world the field is variously referred to as futures studies, strategic foresight, futuristics, futures thinking, futuring, and futurology. Futures studies and strategic foresight are the academic field's most commonly used terms in the English-speaking world.Foresight was the original term and was first used in this sense by H.G. Wells in 1932.[2] "Futurology" is a term common in encyclopedias, though it is used almost exclusively by nonpractitioners today, at least in the English-speaking world. "Futurology" is defined as the "study of the future."[3] The term was coined by German professor Ossip K. Flechtheim[citation needed] in the mid-1940s, who proposed it as a new branch of knowledge that would include a new science of probability. This term may have fallen from favor in recent decades because modern practitioners stress the importance of alternative and plural futures, rather than one monolithic future, and the limitations of prediction and probability, versus the creation of possible and preferable futures.[citation needed]

Three factors usually distinguish futures studies from the research conducted by other disciplines (although all of these disciplines overlap, to differing degrees). First, futures studies often examines not only possible but also probable, preferable, and "wild card" futures. Second, futures studies typically attempts to gain a holistic or systemic view based on insights from a range of different disciplines. Third, futures studies challenges and unpacks the assumptions behind dominant and contending views of the future. The future thus is not empty but fraught with hidden assumptions. For example, many people expect the collapse of the Earth's ecosystem in the near future, while others believe the current ecosystem will survive indefinitely. A foresight approach would seek to analyze and highlight the assumptions underpinning such views.

Futures studies does not generally focus on short term predictions such as interest rates over the next business cycle, or of managers or investors with short-term time horizons. Most strategic planning, which develops operational plans for preferred futures with time horizons of one to three years, is also not considered futures. Plans and strategies with longer time horizons that specifically attempt to anticipate possible future events are definitely part of the field.

The futures field also excludes those who make future predictions through professed supernatural means. At the same time, it does seek to understand the models such groups use and the interpretations they give to these models.

History

Johan Galtung and Sohail Inayatullah[4] argue in Macrohistory and Macrohistorians that the search for grand patterns of social change goes all the way back to Ssu-Ma Chien (145-90BC) and his theory of the cycles of virtue, although the work of Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406) such as The Muqaddimah[5] would be an example that is perhaps more intelligible to modern sociology. Some intellectual foundations of futures studies appeared in the mid-19th century; according to Wendell Bell, Comte's discussion of the metapatterns of social change presages futures studies as a scholarly dialogue.[6]The first works that attempt to make systematic predictions for the future were written in the 18th century. Memoirs of the Twentieth Century written by Samuel Madden in 1733, takes the form of a series of diplomatic letters written in 1997 and 1998 from British representatives in the foreign cities of Constantinople, Rome, Paris, and Moscow.[7] However, the technology of the 20th century is identical to that of Madden's own era - the focus is instead on the political and religious state of the world in the future. Madden went on to write The Reign of George VI, 1900 to 1925, where (in the context of the boom in canal construction at the time) he envisioned a large network of waterways that would radically transform patterns of living - "Villages grew into towns and towns became cities".[8]

The genre of science fiction became established towards the end of the 19th century, with notable writers, including Jules Verne and H. G. Wells, setting their stories in an imagined future world.

Origins

According to W. Warren Wagar, the founder of future studies was H. G. Wells. His Anticipations of the Reaction of Mechanical and Scientific Progress Upon Human Life and Thought: An Experiment in Prophecy, was first serially published in The Fortnightly Review in 1901.[9] Anticipating what the world would be like in the year 2000, the book is interesting both for its hits (trains and cars resulting in the dispersion of population from cities to suburbs; moral restrictions declining as men and women seek greater sexual freedom; the defeat of German militarism, and the existence of a European Union) and its misses (he did not expect successful aircraft before 1950, and averred that "my imagination refuses to see any sort of submarine doing anything but suffocate its crew and founder at sea").[10][11]

Moving from narrow technological predictions, Wells envisioned the eventual collapse of the capitalist world system after a series of destructive total wars. From this havoc would ultimately emerge a world of peace and plenty, controlled by competent technocrats.[9]

The work was a bestseller, and Wells was invited to deliver a lecture at the Royal Institution in 1902, entitled The Discovery of the Future. The lecture was well-received and was soon republished in book form. He advocated for the establishment of a new academic study of the future that would be grounded in scientific methodology rather than just speculation. He argued that a scientifically ordered vision of the future "will be just as certain, just as strictly science, and perhaps just as detailed as the picture that has been built up within the last hundred years to make the geological past." Although conscious of the difficulty in arriving at entirely accurate predictions, he thought that it would still be possible to arrive at a "working knowledge of things in the future".[9]

In his fictional works, Wells predicted the invention and use of the atomic bomb in The World Set Free (1914).[12] In The Shape of Things to Come (1933) the impending World War and cities destroyed by aerial bombardment was depicted.[13] However, he didn't stop advocating for the establishment of a futures science. In a 1933 BBC broadcast he called for the establishment of "Departments and Professors of Foresight", foreshadowing the development of modern academic futures studies by approximately 40 years.[2]

Emergence

Futures studies emerged as an academic discipline in the mid-1960s. First-generation futurists included Herman Kahn, an American Cold War strategist who wrote On Thermonuclear War (1960), Thinking about the unthinkable (1962) and The Year 2000: a framework for speculation on the next thirty-three years (1967); Bertrand de Jouvenel, a French economist who founded Futuribles International in 1960; and Dennis Gabor, a Hungarian-British scientist who wrote Inventing the Future (1963) and The Mature Society. A View of the Future (1972).[6]Future studies had a parallel origin with the birth of systems science in academia, and with the idea of national economic and political planning, most notably in France and the Soviet Union.[6][14] In the 1950s, France was continuing to reconstruct their war-torn country. In the process, French scholars, philosophers, writers, and artists searched for what could constitute a more positive future for humanity. The Soviet Union similarly participated in postwar rebuilding, but did so in the context of an established national economic planning process, which also required a long-term, systemic statement of social goals. Future studies was therefore primarily engaged in national planning, and the construction of national symbols.

By contrast, in the United States of America, futures studies as a discipline emerged from the successful application of the tools and perspectives of systems analysis, especially with regard to quartermastering the war-effort. These differing origins account for an initial schism between futures studies in America and futures studies in Europe: U.S. practitioners focused on applied projects, quantitative tools and systems analysis, whereas Europeans preferred to investigate the long-range future of humanity and the Earth, what might constitute that future, what symbols and semantics might express it, and who might articulate these.[15][16]

By the 1960s, academics, philosophers, writers and artists across the globe had begun to explore enough future scenarios so as to fashion a common dialogue. Inventors such as Buckminster Fuller also began highlighting the effect technology might have on global trends as time progressed. This discussion on the intersection of population growth, resource availability and use, economic growth, quality of life, and environmental sustainability – referred to as the "global problematique" – came to wide public attention with the publication of Limits to Growth, a study sponsored by the Club of Rome.[17]

Further development

International dialogue became institutionalized in the form of the World Futures Studies Federation (WFSF), founded in 1967, with the noted sociologist, Johan Galtung, serving as its first president. In the United States, the publisher Edward Cornish, concerned with these issues, started the World Future Society, an organization focused more on interested laypeople.1975 saw the founding of the first graduate program in futures studies in the United States, the M.S. program in Futures Studies at the University of Houston–Clear Lake,[18] which moved to main campus in 2007 and renamed the degree to Foresight. There followed a year later the M.A. Program in Public Policy in Alternative Futures at the University of Hawaii at Manoa.[19] The Hawaii program provides particular interest in the light of the schism in perspective between European and U.S. futurists; it bridges that schism by locating futures studies within a pedagogical space defined by neo-Marxism, critical political economic theory, and literary criticism. In the years following the foundation of these two programs, single courses in Futures Studies at all levels of education have proliferated, but complete programs occur only rarely.

As a transdisciplinary field, futures studies attracts generalists. This transdisciplinary nature can also cause problems, owing to it sometimes falling between the cracks of disciplinary boundaries; it also has caused some difficulty in achieving recognition within the traditional curricula of the sciences and the humanities. In contrast to "Futures Studies" at the undergraduate level, some graduate programs in strategic leadership or management offer masters or doctorate programs in "strategic foresight" for mid-career professionals, some even online. Nevertheless, comparatively few new PhDs graduate in Futures Studies each year.

The field currently faces the great challenge of creating a coherent conceptual framework, codified into a well-documented curriculum (or curricula) featuring widely accepted and consistent concepts and theoretical paradigms linked to quantitative and qualitative methods, exemplars of those research methods, and guidelines for their ethical and appropriate application within society. As an indication that previously disparate intellectual dialogues have in fact started converging into a recognizable discipline,[20] at least six solidly-researched and well-accepted first attempts to synthesize a coherent framework for the field have appeared: Eleonora Masini's Why Futures Studies,[21] James Dator's Advancing Futures Studies,[22] Ziauddin Sardar's Rescuing all of our Futures,[23] Sohail Inayatullah's Questioning the future,[24] Richard A. Slaughter's The Knowledge Base of Futures Studies,[25] a collection of essays by senior practitioners, and Wendell Bell's two-volume work, The Foundations of Futures Studies.[26]

Probability and predictability

Some aspects of the future, such as celestial mechanics, are highly predictable, and may even be described by relatively simple mathematical models. At present however, science has yielded only a special minority of such "easy to predict" physical processes. Theories such as chaos theory, nonlinear science and standard evolutionary theory have allowed us to understand many complex systems as contingent (sensitively dependent on complex environmental conditions) and stochastic (random within constraints), making the vast majority of future events unpredictable, in any specific case.Not surprisingly, the tension between predictability and unpredictability is a source of controversy and conflict among futures studies scholars and practitioners. Some argue that the future is essentially unpredictable, and that "the best way to predict the future is to create it." Others believe, as Flechtheim, that advances in science, probability, modeling and statistics will allow us to continue to improve our understanding of probable futures, while this area presently remains less well developed than methods for exploring possible and preferable futures.

As an example, consider the process of electing the president of the United States. At one level we observe that any U.S. citizen over 35 may run for president, so this process may appear too unconstrained for useful prediction. Yet further investigation demonstrates that only certain public individuals (current and former presidents and vice presidents, senators, state governors, popular military commanders, mayors of very large cities, etc.) receive the appropriate "social credentials" that are historical prerequisites for election. Thus with a minimum of effort at formulating the problem for statistical prediction, a much reduced pool of candidates can be described, improving our probabilistic foresight. Applying further statistical intelligence to this problem, we can observe that in certain election prediction markets such as the Iowa Electronic Markets, reliable forecasts have been generated over long spans of time and conditions, with results superior to individual experts or polls. Such markets, which may be operated publicly or as an internal market, are just one of several promising frontiers in predictive futures research.

Such improvements in the predictability of individual events do not though, from a complexity theory viewpoint, address the unpredictability inherent in dealing with entire systems, which emerge from the interaction between multiple individual events.

Methodologies

Futures practitioners use a wide range of models and methods (theory and practice), many of which come from other academic disciplines, including economics, sociology, geography, history, engineering, mathematics, psychology, technology, tourism, physics, biology, astronomy, and aspects of theology (specifically, the range of future beliefs).One of the fundamental assumptions in futures studies is that the future is plural not singular, that is, that it consists of alternative futures of varying likelihood but that it is impossible in principle to say with certainty which one will occur. The primary effort in futures studies, therefore, is to identify and describe alternative futures. This effort includes collecting quantitative and qualitative data about the possibility, probability, and desirability of change. The plurality of the term "futures" in futures studies denotes the rich variety of alternative futures, including the subset of preferable futures (normative futures), that can be studied.

Practitioners of the discipline previously concentrated on extrapolating present technological, economic or social trends, or on attempting to predict future trends, but more recently they have started to examine social systems and uncertainties and to build scenarios, question the worldviews behind such scenarios via the causal layered analysis method (and others), create preferred visions of the future, and use backcasting to derive alternative implementation strategies. Apart from extrapolation and scenarios, many dozens of methods and techniques are used in futures research (see below).

Futures studies also includes normative or preferred futures, but a major contribution involves connecting both extrapolated (exploratory) and normative research to help individuals and organisations to build better social futures amid a (presumed) landscape of shifting social changes. Practitioners use varying proportions of inspiration and research. Futures studies only rarely uses the scientific method in the sense of controlled, repeatable and falsifiable experiments with highly standardized methodologies, given that environmental conditions for repeating a predictive scheme are usually quite hard to control. However, many futurists are informed by scientific techniques. Some historians project patterns observed in past civilizations upon present-day society to anticipate what will happen in the future. Oswald Spengler's "Decline of the West" argued, for instance, that western society, like imperial Rome, had reached a stage of cultural maturity that would inexorably lead to decline, in measurable ways.

Futures studies is often summarized as being concerned with "three Ps and a W", or possible, probable, and preferable futures, plus wildcards, which are low probability but high impact events (positive or negative), should they occur. Many futurists, however, do not use the wild card approach. Rather, they use a methodology called Emerging Issues Analysis. It searches for the seeds of change, issues that are likely to move from unknown to the known, from low impact to high impact.

Estimates of probability are involved with two of the four central concerns of foresight professionals (discerning and classifying both probable and wildcard events), while considering the range of possible futures, recognizing the plurality of existing alternative futures, characterizing and attempting to resolve normative disagreements on the future, and envisioning and creating preferred futures are other major areas of scholarship. Most estimates of probability in futures studies are normative and qualitative, though significant progress on statistical and quantitative methods (technology and information growth curves, cliometrics, predictive psychology, prediction markets, etc.) has been made in recent decades.

Futures techniques

While forecasting – i.e., attempts to predict future states from current trends – is a common methodology, professional scenarios often rely on "backcasting": asking what changes in the present would be required to arrive at envisioned alternative future states. For example, the Policy Reform and Eco-Communalism scenarios developed by the Global Scenario Group rely on the backcasting method. Practitioners of futures studies classify themselves as futurists (or foresight practitioners).Futurists use a diverse range of forecasting methods including:

- Anticipatory thinking protocols:

- Causal layered analysis (CLA)

- Environmental scanning

- Scenario method

- Delphi method

- Future history

- Monitoring

- Backcasting (eco-history)

- Cross-impact analysis

- Futures workshops

- Failure mode and effects analysis

- Futures wheel

- Technology roadmapping

- Social network analysis

- Systems engineering

- Trend analysis

- Morphological analysis

- Technology forecasting

Shaping alternative futures

Futurists use scenarios – alternative possible futures – as an important tool. To some extent, people can determine what they consider probable or desirable using qualitative and quantitative methods. By looking at a variety of possibilities one comes closer to shaping the future, rather than merely predicting it. Shaping alternative futures starts by establishing a number of scenarios. Setting up scenarios takes place as a process with many stages. One of those stages involves the study of trends. A trend persists long-term and long-range; it affects many societal groups, grows slowly and appears to have a profound basis. In contrast, a fad operates in the short term, shows the vagaries of fashion, affects particular societal groups, and spreads quickly but superficially.Sample predicted futures range from predicted ecological catastrophes, through a utopian future where the poorest human being lives in what present-day observers would regard as wealth and comfort, through the transformation of humanity into a posthuman life-form, to the destruction of all life on Earth in, say, a nanotechnological disaster.

Futurists have a decidedly mixed reputation and a patchy track record at successful prediction. For reasons of convenience, they often extrapolate present technical and societal trends and assume they will develop at the same rate into the future; but technical progress and social upheavals, in reality, take place in fits and starts and in different areas at different rates.

Many 1950s futurists predicted commonplace space tourism by the year 2000, but ignored the possibilities of ubiquitous, cheap computers, while Marxist expectations have failed to materialise to date. On the other hand, many forecasts have portrayed the future with some degree of accuracy. Current futurists often present multiple scenarios that help their audience envision what "may" occur instead of merely "predicting the future". They claim that understanding potential scenarios helps individuals and organizations prepare with flexibility.

Many corporations use futurists as part of their risk management strategy, for horizon scanning and emerging issues analysis, and to identify wild cards – low probability, potentially high-impact risks.[27] Every successful and unsuccessful business engages in futuring to some degree – for example in research and development, innovation and market research, anticipating competitor behavior and so on.[28][29]

Weak signals, the future sign and wild cards

In futures research "weak signals" may be understood as advanced, noisy and socially situated indicators of change in trends and systems that constitute raw informational material for enabling anticipatory action. There is some confusion about the definition of weak signal by various researchers and consultants. Sometimes it is referred as future oriented information, sometimes more like emerging issues. The confusion has been partly clarified with the concept 'the future sign', by separating signal, issue and interpretation of the future sign.[30]"Wild cards" refer to low-probability and high-impact events, such as existential risks. This concept may be embedded in standard foresight projects and introduced into anticipatory decision-making activity in order to increase the ability of social groups adapt to surprises arising in turbulent business environments. Such sudden and unique incidents might constitute turning points in the evolution of a certain trend or system. Wild cards may or may not be announced by weak signals, which are incomplete and fragmented data from which relevant foresight information might be inferred. Sometimes, mistakenly, wild cards and weak signals are considered as synonyms, which they are not.[31]

Near-term predictions

A long-running tradition in various cultures, and especially in the media, involves various spokespersons making predictions for the upcoming year at the beginning of the year. These predictions sometimes base themselves on current trends in culture (music, movies, fashion, politics); sometimes they make hopeful guesses as to what major events might take place over the course of the next year.Some of these predictions come true as the year unfolds, though many fail. When predicted events fail to take place, the authors of the predictions often state that misinterpretation of the "signs" and portents may explain the failure of the prediction.

Marketers have increasingly started to embrace futures studies, in an effort to benefit from an increasingly competitive marketplace with fast production cycles, using such techniques as trendspotting as popularized by Faith Popcorn.[dubious ]

Trend analysis and forecasting

Mega-trends

Trends come in different sizes. A mega-trend extends over many generations, and in cases of climate, mega-trends can cover periods prior to human existence. They describe complex interactions between many factors. The increase in population from the palaeolithic period to the present provides an example.Potential trends

Possible new trends grow from innovations, projects, beliefs or actions that have the potential to grow and eventually go mainstream in the future. For example, just a few years ago, alternative medicine remained an outcast from modern medicine. Now it has links with big business and has achieved a degree of respectability in some circles and even in the marketplace. This increasing level of acceptance illustrates a potential trend of society to move away from the sciences, even beyond the scope of medicine.Branching trends

Very often, trends relate to one another the same way as a tree-trunk relates to branches and twigs. For example, a well-documented movement toward equality between men and women might represent a branch trend. The trend toward reducing differences in the salaries of men and women in the Western world could form a twig on that branch.Life-cycle of a trend

When a potential trend gets enough confirmation in the various media, surveys or questionnaires to show that it has an increasingly accepted value, behavior or technology, it becomes accepted as a bona fide trend. Trends can also gain confirmation by the existence of other trends perceived as springing from the same branch. Some commentators claim that when 15% to 25% of a given population integrates an innovation, project, belief or action into their daily life then a trend becomes mainstream.Education

Education in the field of futures studies has taken place for some time. Beginning in the United States of America in the 1960s, it has since developed in many different countries. Futures education can encourage the use of concepts, tools and processes that allow students to think long-term, consequentially, and imaginatively. It generally helps students to:- conceptualise more just and sustainable human and planetary futures.

- develop knowledge and skills in exploring probable and preferred futures.

- understand the dynamics and influence that human, social and ecological systems have on alternative futures.

- conscientize responsibility and action on the part of students toward creating better futures.

While futures studies remains a relatively new academic tradition, numerous tertiary institutions around the world teach it. These vary from small programs, or universities with just one or two classes, to programs that incorporate futures studies into other degrees, (for example in planning, business, environmental studies, economics, development studies, science and technology studies). Various formal Masters-level programs exist on six continents. Finally, doctoral dissertations around the world have incorporated futures studies. A recent survey documented approximately 50 cases of futures studies at the tertiary level.[37]

The largest Futures Studies program in the world is at Tamkang University, Taiwan.[citation needed] Futures Studies is a required course at the undergraduate level, with between three to five thousand students taking classes on an annual basis. Housed in the Graduate Institute of Futures Studies is an MA Program. Only ten students are accepted annually in the program. Associated with the program is the Journal of Futures Studies.[38]

The longest running Future Studies program in North America was established in 1975 at The University of Houston-Clear Lake.[39] It moved to the University of Houston main campus in 2007 and renamed the degree to Foresight. The program was established on the belief that if history is studied and taught in an academic setting, then so should the future.

As of 2003, over 40 tertiary education establishments around the world were delivering one or more courses in futures studies. The World Futures Studies Federation[40] has a comprehensive survey of global futures programs and courses. The Acceleration Studies Foundation maintains an annotated list of primary and secondary graduate futures studies programs.[41]

Organizations such as Teach The Future also aim to promote future studies in the secondary school curriculum in order to develop structured approaches to thinking about the future in public school students. The rationale is that a sophisticated approach to thinking about, anticipating, and planning for the future is a core skill requirement that every student should have, similar to literacy and math skills.

Futurists

Several authors have become recognized as futurists. They research trends, particularly in technology, and write their observations, conclusions, and predictions. In earlier eras, many futurists were at academic institutions. John McHale, author of The Future of the Future, published a 'Futures Directory', and directed a think tank called The Centre For Integrative Studies at a university. Futurists have started consulting groups or earn money as speakers, with examples including Alvin Toffler, John Naisbitt and Patrick Dixon. Frank Feather is a business speaker that presents himself as a pragmatic futurist. Some futurists have commonalities with science fiction, and some science-fiction writers, such as Arthur C. Clarke, are known as futurists.[citation needed] In the introduction to The Left Hand of Darkness, Ursula K. Le Guin distinguished futurists from novelists, writing of the study as the business of prophets, clairvoyants, and futurists. In her words, "a novelist's business is lying".A survey of 108 futurists[42] found the following shared assumptions:

- We are in the midst of a historical transformation. Current times are not just part of normal history.

- Multiple perspectives are at heart of futures studies, including unconventional thinking, internal critique, and cross-cultural comparison.

- Consideration of alternatives. Futurists do not see themselves as value-free forecasters, but instead aware of multiple possibilities.

- Participatory futures. Futurists generally see their role as liberating the future in each person, and creating enhanced public ownership of the future. This is true worldwide.[clarification needed]

- Long term policy transformation. While some are more policy-oriented than others, almost all believe that the work of futures studies is to shape public policy, so it consciously and explicitly takes into account the long term.

- Part of the process of creating alternative futures and of influencing public (corporate, or international) policy is internal transformation. At international meetings, structural and individual factors are considered equally important.

- Complexity. Futurists believe that a simple one-dimensional or single-discipline orientation is not satisfactory. Trans-disciplinary approaches that take complexity seriously are necessary. Systems thinking, particularly in its evolutionary dimension, is also crucial.

- Futurists are motivated by change. They are not content merely to describe or forecast. They desire an active role in world transformation.

- They are hopeful for a better future as a "strange attractor".

- Most believe they are pragmatists in this world, even as they imagine and work for another. Futurists have a long term perspective.

- Sustainable futures, understood as making decisions that do not reduce future options, that include policies on nature, gender and other accepted paradigms. This applies to corporate futurists and the NGO. Environmental sustainability is reconciled with the technological, spiritual and post-structural ideals. Sustainability is not a "back to nature" ideal, but rather inclusive of technology and culture.

Applications of foresight and specific fields

General applicability and use of foresight products

Several corporations and government agencies utilize foresight products to both better understand potential risks and prepare for potential opportunities. Several government agencies publish material for internal stakeholders as well as make that material available to broader public. Examples of this include the US Congressional Budget Office long term budget projections,[43] the National Intelligence Center,[44] and the United Kingdom Government Office for Science.[45] Much of this material is used by policy makers to inform policy decisions and government agencies to develop long term plan. Several corporations, particularly those with long product development lifecycles, utilize foresight and future studies products and practitioners in the development of their business strategies. The Shell Corporation is one such entity.[46] Foresight professionals and their tools are increasingly being utilized in both the private and public areas to help leaders deal with an increasingly complex and interconnected world.Fashion and design

Fashion is one area of trend forecasting. The industry typically works 18 months ahead of the current selling season.[citation needed] Large retailers look at the obvious impact of everything from the weather forecast to runway fashion for consumer tastes. Consumer behavior and statistics are also important for a long-range forecast.Artists and conceptual designers, by contrast, may feel that consumer trends are a barrier to creativity. Many of these ‘startists’ start micro trends but do not follow trends themselves.[citation needed]

Design is another area of trend forecasting. Foresight and futures thinking are rapidly being adopted by the design industry to insure more sustainable, robust and humanistic products. Design, much like future studies is an interdisciplinary field that considers global trends, challenges and opportunities to foster innovation. Designers are thus adopting futures methodologies including scenarios, trend forecasting, and futures research.

Holistic thinking that incorporates strategic, innovative and anticipatory solutions gives designers the tools necessary to navigate complex problems and develop novel future enhancing and visionary solutions.

The Association for Professional Futurists has also held meetings discussing the ways in which Design Thinking and Futures Thinking intersect.

Energy and alternative sources

While the price of oil probably will go down and up, the basic price trajectory is sharply up. Market forces will play an important role, but there are not enough new sources of oil in the Earth to make up for escalating demands from China, India, and the Middle East, and to replace declining fields. And while many alternative sources of energy exist in principle, none exists in fact in quality or quantity sufficient to make up for the shortfall of oil soon enough. A growing gap looms between the effective end of the Age of Oil and the possible emergence of new energy sources.[47]Education

As Foresight has expanded to include a broader range of social concerns all levels and types of education have been addressed, including formal and informal education. Many countries are beginning to implement Foresight in their Education policy. A few programs are listed below:- Finland's FinnSight 2015[48] - Implementation began in 2006 and though at the time was not referred to as "Foresight" they tend to display the characteristics of a foresight program.

- Singapore's Ministry of Education Master plan for Information Technology in Education[49] - This third Masterplan continues what was built on in the 1st and 2nd plans to transform learning environments to equip students to compete in a knowledge economy.

Science Fiction

Wendell Bell and Ed Cornish acknowledge science fiction as a catalyst to future studies, conjuring up visions of tomorrow.[50] Science fiction’s potential to provide an “imaginative social vision” is its contribution to futures studies and public perspective. Productive sci-fi presents plausible, normative scenarios.[50] Jim Dator attributes the foundational concepts of “images of the future” to Wendell Bell, for clarifying Fred Polak’s concept in Images of the Future, as it applies to futures studies.[51][52] Similar to futures studies’ scenarios thinking, empirically supported visions of the future are a window into what the future could be. Pamela Sargent states, “Science fiction reflects attitudes typical of this century.” She gives a brief history of impactful sci-fi publications, like The Foundation Trilogy, by Isaac Asimov and Starship Troopers, by Robert A. Heinlein.[53] Alternate perspectives validate sci-fi as part of the fuzzy “images of the future.”[52] However, the challenge is the lack of consistent futures research based literature frameworks.[53] Ian Miles reviews The New Encyclopedia of Science Fiction,” identifying ways Science Fiction and Futures Studies “cross-fertilize, as well as the ways in which they differ distinctly.” Science Fiction cannot be simply considered fictionalized Futures Studies. It may have aims other than “prediction, and be no more concerned with shaping the future than any other genre of literature.” [54] It is not to be understood as an explicit pillar of futures studies, due to its inconsistency of integrated futures research. Additionally, Dennis Livingston, a literature and Futures journal critic says, “The depiction of truly alternative societies has not been one of science fiction’s strong points, especially” preferred, normative envisages.[55]Research centers

- Graduate Degree in Foresight, University of Houston[56]

- Institute for Futures Research, University of Stellenbosch

- Copenhagen Institute for Futures Studies

- The Finland Futures Research Centre (FFRC)

- The Foresight Programme, London, Department for Business, Innovation and Skills

- The Futures Academy, Dublin Institute of Technology, Ireland

- Hawaii Research Center for Futures Studies, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa

- Institute for Futures Research, South Africa

- Institute for the Future, Palo Alto, California

- National Intelligence Council, Office of the Director of National Intelligence, Washington DC

- Singularity Institute, Singularity Institute for Artificial Intelligence

- Tellus Institute, Boston MA

- World Future Society

- World Futures Studies Federation, world

- Future of Humanity Institute

- Italian Institute for the Future, Naples, Italy[57]

Futurists and foresight thought leaders

- Daniel Bell

- Peter C. Bishop

- Nick Bostrom

- Jamais Cascio

- Arthur C. Clarke[58]

- Jim Dator

- Leonardo da Vinci (Flight)

- Nicolas De Santis

- Peter Diamandis

- Mahdi Elmandjra

- Jacque Fresco[59]

- George Friedman

- Hugo de Garis

- Jennifer M. Gidley

- Ben Goertzel

- Arthur Harkins

- Stephen Hawking[60][61]

- Aldous Huxley ("Brave New World")

- Sohail Inayatullah

- Mitchell Joachim

- Bill Joy

- Robert Jungk

- Herman Kahn

- Michio Kaku

- Ray Kurzweil

- Max More

- George Orwell ("Nineteen Eighty-Four")

- David Passig

- Kim Stanley Robinson

- Michel Saloff Coste

- Anders Sandberg

- Peter Schwartz

- John Smart

- Mark Stevenson ("An Optimist's Tour of the Future")

- Alvin Toffler ("Future Shock")

- Jules Verne ("From the Earth to the Moon")

- Natasha Vita-More

- H. G. Wells (World Brain)

- Eliezer Yudkowsky

Books

Periodicals and monographs

- International Journal of Forecasting

- Journal of Futures Studies

- Technological Forecasting and Social Change

- The Futurist World Future Society