From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Meteorology is the interdisciplinary scientific study of the atmosphere. Studies in the field stretch back millennia, though significant progress in meteorology did not occur until the 18th century. The 19th century saw modest progress in the field after observing networks formed across several countries. It wasn't until after the development of the computer in the latter half of the 20th century that significant breakthroughs in weather forecasting were achieved.

Meteorological phenomena are observable weather events which illuminate, and are explained by the science of meteorology. Those events are bound by the variables that exist in Earth's atmosphere; temperature, air pressure, water vapor, and the gradients and interactions of each variable, and how they change in time. Different spatial scales are studied to determine how systems on local, regional, and global levels impact weather and climatology.

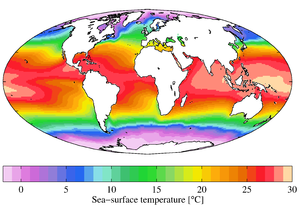

Meteorology, climatology, atmospheric physics, and atmospheric chemistry are sub-disciplines of the atmospheric sciences. Meteorology and hydrology compose the interdisciplinary field of hydrometeorology. Interactions between Earth's atmosphere and the oceans are part of coupled ocean-atmosphere studies. Meteorology has application in many diverse fields such as the military, energy production, transport, agriculture and construction.

The word "meteorology" is from Greek μετέωρος metéōros "lofty; high (in the sky)" (from μετα- meta- "above" and ἀείρω aeiro "I lift up") and -λογία -logia "-(o)logy", i.e. "the study of things in the air".

History

The beginnings of meteorology can be traced back to ancient India,[1] as the Upanishads contain serious discussion about the processes of cloud formation and rain and the seasonal cycles caused by the movement of earth around the sun. Varāhamihira's classical work Brihatsamhita, written about 500 AD,[1] provides clear evidence that a deep knowledge of atmospheric processes existed even in those times.

In 350 BC, Aristotle wrote Meteorology.[2] Aristotle is considered the founder of meteorology.[3] One of the most impressive achievements described in the Meteorology is the description of what is now known as the hydrologic cycle.[4] The Greek scientist Theophrastus compiled a book on weather forecasting, called the Book of Signs. The work of Theophrastus remained a dominant influence in the study of weather and in weather forecasting for nearly 2,000 years.[5] In 25 AD, Pomponius Mela, a geographer for the Roman Empire, formalized the climatic zone system.[6] According to Toufic Fahd, around the 9th century, Al-Dinawari wrote the Kitab al-Nabat (Book of Plants), in which he deals with the application of meteorology to agriculture during the Muslim Agricultural Revolution. He describes the meteorological character of the sky, the planets and constellations, the sun and moon, the lunar phases indicating seasons and rain, the anwa (heavenly bodies of rain), and atmospheric phenomena such as winds, thunder, lightning, snow, floods, valleys, rivers, lakes.[7][8][verification needed]

Research of visual atmospheric phenomena

St. Albert the Great was the first to propose that each drop of falling rain had the form of a small sphere, and that this form meant that the rainbow was produced by light interacting with each raindrop.[11] Roger Bacon was the first to calculate the angular size of the rainbow. He stated that the rainbow summit can not appear higher than 42 degrees above the horizon.[12] In the late 13th century and early 14th century, Kamāl al-Dīn al-Fārisī and Theodoric of Freiberg were the first to give the correct explanations for the primary rainbow phenomenon. Theoderic went further and also explained the secondary rainbow.[13] In 1716, Edmund Halley suggested that aurorae are caused by "magnetic effluvia" moving along the Earth's magnetic field lines.

Instruments and classification scales

In 1441, King Sejong's son, Prince Munjong, invented the first standardized rain gauge.[citation needed] These were sent throughout the Joseon Dynasty of Korea as an official tool to assess land taxes based upon a farmer's potential harvest. In 1450, Leone Battista Alberti developed a swinging-plate anemometer, and was known as the first anemometer.[14] In 1607, Galileo Galilei constructed a thermoscope. In 1611, Johannes Kepler wrote the first scientific treatise on snow crystals: "Strena Seu de Nive Sexangula (A New Year's Gift of Hexagonal Snow)".[15] In 1643, Evangelista Torricelli invented the mercury barometer.[14] In 1662, Sir Christopher Wren invented the mechanical, self-emptying, tipping bucket rain gauge. In 1714, Gabriel Fahrenheit created a reliable scale for measuring temperature with a mercury-type thermometer.[16] In 1742, Anders Celsius, a Swedish astronomer, proposed the "centigrade" temperature scale, the predecessor of the current Celsius scale.[17] In 1783, the first hair hygrometer was demonstrated by Horace-Bénédict de Saussure. In 1802–1803, Luke Howard wrote On the Modification of Clouds in which he assigns cloud types Latin names.[18] In 1806, Francis Beaufort introduced his system for classifying wind speeds.[19] Near the end of the 19th century the first cloud atlases were published, including the International Cloud Atlas, which has remained in print ever since. The April 1960 launch of the first successful weather satellite, TIROS-1, marked the beginning of the age where weather information became available globally.

Atmospheric composition research

In 1648, Blaise Pascal rediscovered that atmospheric pressure decreases with height, and deduced that there is a vacuum above the atmosphere.[20] In 1738, Daniel Bernoulli published Hydrodynamics, initiating the kinetic theory of gases and established the basic laws for the theory of gases.[21] In 1761, Joseph Black discovered that ice absorbs heat without changing its temperature when melting. In 1772, Black's student Daniel Rutherford discovered nitrogen, which he called phlogisticated air, and together they developed the phlogiston theory.[22] In 1777, Antoine Lavoisier discovered oxygen and developed an explanation for combustion.[23] In 1783, in Lavoisier's book Reflexions sur le phlogistique,[24] he deprecates the phlogiston theory and proposes a caloric theory.[25][26] In 1804, Sir John Leslie observed that a matte black surface radiates heat more effectively than a polished surface, suggesting the importance of black body radiation. In 1808, John Dalton defended caloric theory in A New System of Chemistry and described how it combines with matter, especially gases; he proposed that the heat capacity of gases varies inversely with atomic weight. In 1824, Sadi Carnot analyzed the efficiency of steam engines using caloric theory; he developed the notion of a reversible process and, in postulating that no such thing exists in nature, laid the foundation for the second law of thermodynamics.Research into cyclones and air flow

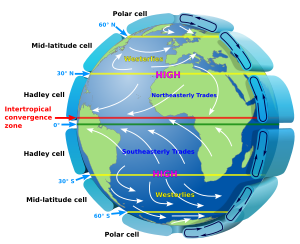

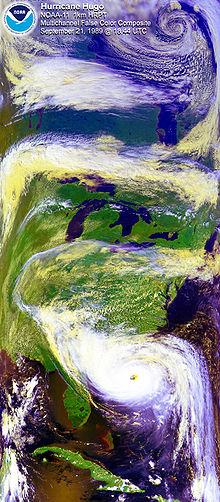

In 1494, Christopher Columbus experienced a tropical cyclone, which led to the first written European account of a hurricane.[27] In 1686, Edmund Halley presented a systematic study of the trade winds and monsoons and identified solar heating as the cause of atmospheric motions.[28] In 1735, an ideal explanation of global circulation through study of the trade winds was written by George Hadley.[29] In 1743, when Benjamin Franklin was prevented from seeing a lunar eclipse by a hurricane, he decided that cyclones move in a contrary manner to the winds at their periphery.[30] Understanding the kinematics of how exactly the rotation of the earth affects airflow was partial at first. Gaspard-Gustave Coriolis published a paper in 1835 on the energy yield of machines with rotating parts, such as waterwheels.[31] In 1856, William Ferrel proposed the existence of a circulation cell in the mid-latitudes, with air being deflected by the Coriolis force to create the prevailing westerly winds.[32] Late in the 19th century, the full extent of the large-scale interaction of pressure gradient force and deflecting force that in the end causes air masses to move along isobars was understood. By 1912, this deflecting force was named the Coriolis effect.[33] Just after World War I, a group of meteorologists in Norway led by Vilhelm Bjerknes developed the Norwegian cyclone model that explains the generation, intensification and ultimate decay (the life cycle) of mid-latitude cyclones, introducing the idea of fronts, that is, sharply defined boundaries between air masses.[34] The group included Carl-Gustaf Rossby (who was the first to explain the large scale atmospheric flow in terms of fluid dynamics), Tor Bergeron (who first determined the mechanism by which rain forms) and Jacob Bjerknes.Observation networks and weather forecasting

In 1654, Ferdinando II de Medici established the first weather observing network, that consisted of meteorological stations in Florence, Cutigliano, Vallombrosa, Bologna, Parma, Milan, Innsbruck, Osnabrück, Paris and Warsaw.Collected data were centrally sent to Florence at regular time intervals.[35] In 1832, an electromagnetic telegraph was created by Baron Schilling.[36] The arrival of the electrical telegraph in 1837 afforded, for the first time, a practical method for quickly gathering surface weather observations from a wide area.[37] This data could be used to produce maps of the state of the atmosphere for a region near the earth's surface and to study how these states evolved through time. To make frequent weather forecasts based on these data required a reliable network of observations, but it was not until 1849 that the Smithsonian Institution began to establish an observation network across the United States under the leadership of Joseph Henry.[38] Similar observation networks were established in Europe at this time. In 1854, the United Kingdom government appointed Robert FitzRoy to the new office of Meteorological Statist to the Board of Trade with the role of gathering weather observations at sea. FitzRoy's office became the United Kingdom Meteorological Office in 1854, the first national meteorological service in the world. The first daily weather forecasts made by FitzRoy's Office were published in The Times newspaper in 1860. The following year a system was introduced of hoisting storm warning cones at principal ports when a gale was expected.

Over the next 50 years many countries established national meteorological services. The India Meteorological Department (1875) was established following tropical cyclone and monsoon related famines in the previous decades.[39] The Finnish Meteorological Central Office (1881) was formed from part of Magnetic Observatory of Helsinki University.[40] Japan's Tokyo Meteorological Observatory, the forerunner of the Japan Meteorological Agency, began constructing surface weather maps in 1883.[41] The United States Weather Bureau (1890) was established under the United States Department of Agriculture. The Australian Bureau of Meteorology (1906) was established by a Meteorology Act to unify existing state meteorological services.[42][43]

Numerical weather prediction

Main article: Numerical weather prediction

In 1904, Norwegian scientist Vilhelm Bjerknes first argued in his paper Weather Forecasting as a Problem in Mechanics and Physics that it should be possible to forecast weather from calculations based upon natural laws.[44][45]

It was not until later in the 20th century that advances in the understanding of atmospheric physics led to the foundation of modern numerical weather prediction. In 1922, Lewis Fry Richardson published "Weather Prediction By Numerical Process",[46] after finding notes and derivations he worked on as an ambulance driver in World War I. He described therein how small terms in the prognostic fluid dynamics equations governing atmospheric flow could be neglected, and a finite differencing scheme in time and space could be devised, to allow numerical prediction solutions to be found. Richardson envisioned a large auditorium of thousands of people performing the calculations and passing them to others. However, the sheer number of calculations required was too large to be completed without the use of computers, and the size of the grid and time steps led to unrealistic results in deepening systems. It was later found, through numerical analysis, that this was due to numerical instability.

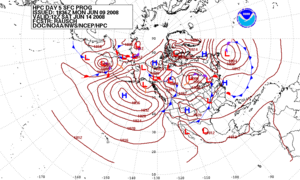

Starting in the 1950s, numerical forecasts with computers became feasible.[47] The first weather forecasts derived this way used barotropic (single-vertical-level) models, and could successfully predict the large-scale movement of midlatitude Rossby waves, that is, the pattern of atmospheric lows and highs.[48] In 1959, the UK Meteorological Office received its first computer, a Ferranti Mercury.[citation needed]

In the 1960s, the chaotic nature of the atmosphere was first observed and mathematically described by Edward Lorenz, founding the field of chaos theory.[49] These advances have led to the current use of ensemble forecasting in most major forecasting centers, to take into account uncertainty arising from the chaotic nature of the atmosphere.[50] Climate models have been developed that feature a resolution comparable to older weather prediction models. These climate models are used to investigate long-term climate shifts, such as what effects might be caused by human emission of greenhouse gases.

Meteorologists

Meteorologists are scientists who study meteorology.[51] The American Meteorological Society published and continually updates an authoritative electronic Meteorology Glossary.[52] Meteorologists work in government agencies, private consulting and research services, industrial enterprises, utilities, radio and television stations, and in education. In the United States, meteorologists held about 9,400 jobs in 2009.[53]Meteorologists are best known by the public for weather forecasting. Some radio and television weather forecasters are professional meteorologists, while others are reporters (weather specialist, weatherman, etc.) with no formal meteorological training. The American Meteorological Society and National Weather Association issue "Seals of Approval" to weather broadcasters who meet certain requirements.

Equipment

Sets of surface measurements are important data to meteorologists. They give a snapshot of a variety of weather conditions at one single location and are usually at a weather station, a ship or a weather buoy. The measurements taken at a weather station can include any number of atmospheric observables. Usually, temperature, pressure, wind measurements, and humidity are the variables that are measured by a thermometer, barometer, anemometer, and hygrometer, respectively.[54] Upper air data are of crucial importance for weather forecasting. The most widely used technique is launches of radiosondes. Supplementing the radiosondes a network of aircraft collection is organized by the World Meteorological Organization.

Remote sensing, as used in meteorology, is the concept of collecting data from remote weather events and subsequently producing weather information. The common types of remote sensing are Radar, Lidar, and satellites (or photogrammetry). Each collects data about the atmosphere from a remote location and, usually, stores the data where the instrument is located. Radar and Lidar are not passive because both use EM radiation to illuminate a specific portion of the atmosphere.[55] Weather satellites along with more general-purpose Earth-observing satellites circling the earth at various altitudes have become an indispensable tool for studying a wide range of phenomena from forest fires to El Niño.

Spatial scales

In the study of the atmosphere, meteorology can be divided into distinct areas of emphasis depending on the temporal scope and spatial scope of interest. At one extreme of this scale is climatology. In the timescales of hours to days, meteorology separates into micro-, meso-, and synoptic scale meteorology. Respectively, the geospatial size of each of these three scales relates directly with the appropriate timescale.Other subclassifications are available based on the need by or by the unique, local or broad effects that are studied within that sub-class.

Microscale

Microscale meteorology is the study of atmospheric phenomena of about 1 km or less. Individual thunderstorms, clouds, and local turbulence caused by buildings and other obstacles (such as individual hills) fall within this category.[56]Mesoscale

Mesoscale meteorology is the study of atmospheric phenomena that has horizontal scales ranging from microscale limits to synoptic scale limits and a vertical scale that starts at the Earth's surface and includes the atmospheric boundary layer, troposphere, tropopause, and the lower section of the stratosphere. Mesoscale timescales last from less than a day to the lifetime of the event, which in some cases can be weeks. The events typically of interest are thunderstorms, squall lines, fronts, precipitation bands in tropical and extratropical cyclones, and topographically generated weather systems such as mountain waves and sea and land breezes.[57]Synoptic scale

Global scale

Global scale meteorology is study of weather patterns related to the transport of heat from the tropics to the poles. Also, very large scale oscillations are of importance. These oscillations have time periods typically on the order of months, such as the Madden-Julian Oscillation, or years, such as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation and the Pacific decadal oscillation. Global scale pushes the thresholds of the perception of meteorology into climatology. The traditional definition of climate is pushed into larger timescales with the further understanding of how the global oscillations cause both climate and weather disturbances in the synoptic and mesoscale timescales.

Numerical Weather Prediction is a main focus in understanding air–sea interaction, tropical meteorology, atmospheric predictability, and tropospheric/stratospheric processes.[59] The Naval Research Laboratory in Monterey California developed a global atmospheric model called Navy Operational Global Atmospheric Prediction System (NOGAPS). NOGAPS is run operationally at Fleet Numerical Meteorology and Oceanography Center for the United States Military. Many other global atmospheric models are run by national meteorological agencies.

Some meteorological principles

Boundary layer meteorology

Boundary layer meteorology is the study of processes in the air layer directly above earth's surface, known as the atmospheric boundary layer (ABL). The effects of the surface – heating, cooling, and friction – cause turbulent mixing within the air layer. Significant fluxes of heat, matter, or momentum on time scales of less than a day are advected by turbulent motions.[60] Boundary layer meteorology includes the study of all types of surface–atmosphere boundary, including ocean, lake, urban land and non-urban land for the study of meteorology.Dynamic meteorology

Dynamic meteorology generally focuses on the fluid dynamics of the atmosphere. The idea of air parcel is used to define the smallest element of the atmosphere, while ignoring the discrete molecular and chemical nature of the atmosphere. An air parcel is defined as a point in the fluid continuum of the atmosphere. The fundamental laws of fluid dynamics, thermodynamics, and motion are used to study the atmosphere. The physical quantities that characterize the state of the atmosphere are temperature, density, pressure, etc. These variables have unique values in the continuum.[61]Applications

Weather forecasting

Once an all-human endeavor based mainly upon changes in barometric pressure, current weather conditions, and sky condition,[65][66] forecast models are now used to determine future conditions. Human input is still required to pick the best possible forecast model to base the forecast upon, which involves pattern recognition skills, teleconnections, knowledge of model performance, and knowledge of model biases. The chaotic nature of the atmosphere, the massive computational power required to solve the equations that describe the atmosphere, error involved in measuring the initial conditions, and an incomplete understanding of atmospheric processes mean that forecasts become less accurate as the difference in current time and the time for which the forecast is being made (the range of the forecast) increases. The use of ensembles and model consensus help narrow the error and pick the most likely outcome.[67][68][69]

There are a variety of end uses to weather forecasts. Weather warnings are important forecasts because they are used to protect life and property.[70] Forecasts based on temperature and precipitation are important to agriculture,[71][72][73][74] and therefore to commodity traders within stock markets. Temperature forecasts are used by utility companies to estimate demand over coming days.[75][76][77] On an everyday basis, people use weather forecasts to determine what to wear on a given day. Since outdoor activities are severely curtailed by heavy rain, snow and the wind chill, forecasts can be used to plan activities around these events, and to plan ahead and survive them.

Aviation meteorology

Aviation meteorology deals with the impact of weather on air traffic management. It is important for air crews to understand the implications of weather on their flight plan as well as their aircraft, as noted by the Aeronautical Information Manual:[78]The effects of ice on aircraft are cumulative—thrust is reduced, drag increases, lift lessens, and weight increases. The results are an increase in stall speed and a deterioration of aircraft performance. In extreme cases, 2 to 3 inches of ice can form on the leading edge of the airfoil in less than 5 minutes. It takes but 1/2 inch of ice to reduce the lifting power of some aircraft by 50 percent and increases the frictional drag by an equal percentage.[79]

Agricultural meteorology

Meteorologists, soil scientists, agricultural hydrologists, and agronomists are persons concerned with studying the effects of weather and climate on plant distribution, crop yield, water-use efficiency, phenology of plant and animal development, and the energy balance of managed and natural ecosystems. Conversely, they are interested in the role of vegetation on climate and weather.[80]Hydrometeorology

Hydrometeorology is the branch of meteorology that deals with the hydrologic cycle, the water budget, and the rainfall statistics of storms.[81] A hydrometeorologist prepares and issues forecasts of accumulating (quantitative) precipitation, heavy rain, heavy snow, and highlights areas with the potential for flash flooding. Typically the range of knowledge that is required overlaps with climatology, mesoscale and synoptic meteorology, and other geosciences.[82]The multidisciplinary nature of the branch can result in technical challenges, since tools and solutions from each of the individual disciplines involved may behave slightly differently, be optimized for different hard- and software platforms and use different data formats. There are some initiatives - such as the DRIHM project[83] - that are trying to address this issue.[84]

is the fluid density, u is the

is the fluid density, u is the

, the net force due to

, the net force due to

is the viscous dissipation function. The viscous dissipation function governs the rate at which mechanical energy of the flow is converted to heat. The

is the viscous dissipation function. The viscous dissipation function governs the rate at which mechanical energy of the flow is converted to heat. The