|

|

|

|

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Nicorette, Nicotrol |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Dependence liability |

Physical: low–moderate Psychological: moderate–high[1][2] |

| Addiction liability |

High[3] |

| Routes of administration |

Inhalation; insufflation; oral – buccal, sublingual, and ingestion; transdermal; rectal |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | <5 td=""> |

| Metabolism | Primarily hepatic: CYP2A6, CYP2B6, FMO3, others |

| Metabolites | Cotinine |

| Biological half-life | 1-2 hours; 20 hours active metabolite |

| Excretion | Urine (10-20% (gum), pH-dependent; 30% (inhaled); 10-30% (intranasal)) |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.177 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C10H14N2 |

| Molar mass | 162.23 g/mol |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Chiral |

| Density | 1.01 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | −79 °C (−110 °F) |

| Boiling point | 247 °C (477 °F) |

| |

|

Nicotine is a potent parasympathomimetic stimulant and an alkaloid found in the nightshade family of plants. Nicotine acts as an agonist at most nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs),[4][5] except at two nicotinic receptor subunits (nAChRα9 and nAChRα10) where it acts as a receptor antagonist.[4] Nicotine is found in the leaves of Nicotiana rustica, in amounts of 2–14%; in the tobacco plant, Nicotiana tabacum; in Duboisia hopwoodii; and in Asclepias syriaca.[6]

Nicotine constitutes approximately 0.6–3.0% of the dry weight of tobacco.[7] It also occurs in edible plants, such Solanaceae, which include eggplants, potatoes, and tomatoes, but at trace levels generally under 200 nanograms per gram, dry weight (less than .00002%).[8][9][10] Nicotine functions as an antiherbivore chemical; consequently, nicotine was widely used as an insecticide in the past,[11][12] and neonicotinoids, such as imidacloprid, are widely used.

Nicotine is highly addictive.[13][14] An average cigarette yields about 2 mg of absorbed nicotine; in lesser doses of that order, the substance acts as a stimulant in mammals, while high amounts (50–100 mg) can be harmful.[15][16][17] This stimulant effect is a contributing factor to the addictive properties of tobacco smoking. Nicotine's addictive nature includes psychoactive effects, drug-reinforced behavior, compulsive use, relapse after abstinence, physical dependence and tolerance.[18]

Beyond addiction, both short and long-term nicotine exposure have not been established as dangerous to adults,[19] except among certain vulnerable groups.[20] At high-enough doses, nicotine is associated with poisonings and is potentially lethal.[17][21] Nicotine as a tool for quitting smoking has a good safety history.[22] There is inadequate research to show that nicotine itself is associated with cancer in humans.[21] Nicotine in the form of nicotine replacement products is less of a cancer risk than smoking.[21] Nicotine is linked to possible birth defects.[23] During pregnancy, there are risks to the child later in life for type 2 diabetes, obesity, hypertension, neurobehavioral defects, respiratory dysfunction, and infertility.[22] The use of electronic cigarettes, which are designed to be refilled with nicotine-containing e-liquid, has raised concerns over nicotine overdoses, especially with regard to the possibility of young children ingesting the liquids.[24]

Psychoactive effects

Nicotine's mood-altering effects are different by report: in particular it is both a stimulant and a relaxant.[25] First causing a release of glucose from the liver and epinephrine (adrenaline) from the adrenal medulla, it causes stimulation. Users report feelings of relaxation, sharpness, calmness, and alertness.[26]When a cigarette is smoked, nicotine-rich blood passes from the lungs to the brain within seven seconds and immediately stimulates nicotinic acetylcholine receptors; this indirectly promotes the release of many chemical messengers such as acetylcholine, norepinephrine, epinephrine, arginine vasopressin, serotonin, dopamine, and beta-endorphin in parts of the brain.[27][28] Nicotine also extends the duration of positive effects of dopamine and increases the sensitivity of the brain's reward system to rewarding stimuli.[29][30] Most cigarettes contain 1–3 milligrams of inhalable nicotine.[31][unreliable source?] Studies suggest that when smokers wish to achieve a stimulating effect, they take short quick puffs, which produce a low level of blood nicotine.[32][needs update]

Nicotine is unusual in comparison to most drugs, as its profile changes from stimulant to sedative with increasing dosages, a phenomenon known as "Nesbitt's paradox" after the doctor who first described it in 1969.[33][34] At very high doses it dampens neuronal activity.[35]

Uses

Medical

A 21 mg patch applied to the left arm. The Cochrane Collaboration finds that nicotine replacement therapy increases a quitter's chance of success by 50% to 70%.[36]

The primary therapeutic use of nicotine is in treating nicotine dependence in order to eliminate smoking with the damage it does to health. Controlled levels of nicotine are given to patients through gums, dermal patches, lozenges, electronic/substitute cigarettes or nasal sprays in an effort to wean them off their dependence. Studies have found that these therapies increase the chance of success of quitting by 50 to 70%,[36] though reductions in the population as a whole have not been demonstrated.[37]

Enhancing performance

Nicotine is frequently used for its performance-enhancing effects on cognition, alertness, and focus.[38] A meta-analysis of 41 double-blind, placebo-controlled studies concluded that nicotine or smoking had significant positive effects on aspects of fine motor abilities, alerting and orienting attention, and episodic and working memory.[39] A 2015 review noted that stimulation of the α4β2 nicotinic receptor is responsible for certain improvements in attentional performance;[40] among the nicotinic receptor subtypes, nicotine has the highest binding affinity at the α4β2 receptor (ki=1 nM), which is also the biological target that mediates nicotine's addictive properties.[41] Nicotine has potential beneficial effects, but it also has paradoxical effects, which may be due to its inverted U-shape or pharmacokinetic features.[42]Recreational

Nicotine is commonly consumed as a recreational drug for its stimulant effects.[43] Recreational nicotine products include chewing tobacco, cigars, cigarettes, e-cigarettes, snuff, pipe tobacco, and snus.Adverse effects

Limited data exists on the health effects of long-term use of pure nicotine, because nicotine is usually consumed via tobacco products.[44] The long-term use of nicotine in the form of snus incurs a slight risk of cardiovascular disease compared to tobacco smoking[44] and is not associated with cancer.[45][not in citation given] Nicotine is one of the most rigorously studied drugs.[46] The complex effects of nicotine are not entirely understood.[23] Studies of continued use of nicotine replacement products in those who have stopped smoking found no adverse effects from months to several years, and that people with cardiovascular disease were able to tolerate them for 12 weeks.[44] The general medical position is that nicotine itself, in small doses[failed verification], poses few health risks, except among certain vulnerable groups.[20] A 2016 Royal College of Physicians report found "nicotine alone in the doses used by smokers represents little if any hazard to the user".[47] A 2014 American Heart Association policy statement found that some health concerns relate to nicotine.[44] Experimental research suggests that adolescent nicotine use may harm brain development.[21] Children exposed to nicotine may have a number of lifelong health issues.[14] Administration of nicotine to guinea pigs has been shown to cause harm to cells of the inner ear.[48][unreliable medical source?] As medicine, nicotine is used to help with quitting smoking and has good safety in this form.[22]Metabolism and body weight

By reducing the appetite and raising the metabolism, some smokers may lose weight as a consequence.[49][50] By increasing metabolic rate and inhibiting the usual compensatory increase in appetite, the body weight of smokers is lower on average than that of non-smokers. When smokers quit, they gain on average 5–6 kg weight, returning to the average weight of non-smokers.[51]Vascular system

Human epidemiology studies show that nicotine use is not a significant cause of cardiovascular disease.[52] A 2015 review found that nicotine is associated with cardiovascular disease.[23] A 2016 review suggests that "the risks of nicotine without tobacco combustion products (cigarette smoke) are low compared to cigarette smoking, but are still of concern in people with cardiovascular disease."[53] Some studies in people show the possibility that nicotine contributes to acute cardiovascular events in smokers with established cardiovascular disease, and induces pharmacologic effects that might contribute to increased atherosclerosis.[53] Prolonged nicotine use seems not to increase atherosclerosis.[53] Brief nicotine use, such as nicotine medicine, seems to incur a slight cardiovascular risk, even to people with established cardiovascular disease.[53] A 2015 review found "Nicotine in vitro and in animal models can inhibit apoptosis and enhance angiogenesis, effects that raise concerns about the role of nicotine in promoting the acceleration of atherosclerotic disease."[54] A 2012 Cochrane review found no evidence of an increased risk of cardiovascular disease with nicotine replacement products.[55] A 1996 randomized controlled trial using nicotine patches found that serious adverse events were not more frequent among smokers with cardiovascular disease.[55] A meta-analysis shows that snus consumption, which delivers nicotine at a dose equivalent to that of cigarettes, is not associated with heart attacks.[56] Hence, it is not nicotine, but tobacco smoke's other components which seem to be implicated in ischemic heart disease.[56] Nicotine increases heart rate and blood pressure[57] and induces abnormal heart rhythms.[58] Nicotine can also induce potentially atherogenic genes in human coronary artery endothelial cells.[59] Microvascular injury can result through its action on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs).[60] Nicotine does not adversely affect serum cholesterol levels,[52] but a 2015 review found it may elevate serum cholesterol levels.[23] Many quitting smoking studies using nicotine medicines report lowered dyslipidemia with considerable benefit in HDL/LDL ratios.[53] Nicotine supports clot formation and aids in plaque formation by enhancing vascular smooth muscle.[23]Cancer

Possible side effects of nicotine.[61]

Although there is insufficient evidence to classify nicotine as a carcinogen, there is an ongoing debate about whether it functions as a tumor promoter.[62] In vitro studies have associated it with cancer, but carcinogenicity has not been demonstrated in vivo.[23] There is inadequate research to demonstrate that nicotine is associated with cancer in humans, but there is evidence indicating possible oral, esophageal, or pancreatic cancer risks.[21] Nicotine in the form of nicotine replacement products is less of a cancer risk than smoking.[21] Nicotine replacement products have not been shown to be associated with cancer in the real world.[23]

While no epidemiological evidence directly supports the notion that nicotine acts as a carcinogen in the formation of human cancer, research has identified nicotine's indirect involvement in cancer formation in animal models and cell cultures.[63][64][65] Nicotine increases cholinergic signalling and adrenergic signalling in the case of colon cancer,[66] thereby impeding apoptosis (programmed cell death), promoting tumor growth, and activating growth factors and cellular mitogenic factors such as 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX), and epidermal growth factor (EGF). Nicotine also promotes cancer growth by stimulating angiogenesis and neovascularization.[67][68] In one study, nicotine administered to mice with tumors caused increases in tumor size (twofold increase), metastasis (nine-fold increase), and tumor recurrence (threefold increase).[69] N-Nitrosonornicotine (NNN), classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) as a Group 1 carcinogen, has been shown to form in vitro from nornicotine in human saliva, indicating nornicotine is a carcinogen precursor.[70] The IARC has not evaluated pure nicotine or assigned it to an official carcinogenic classification.

In cancer cells, nicotine promotes the epithelial–mesenchymal transition which makes the cancer cells more resistant to drugs that treat cancer.[71]

Fetal development

In pregnancy, a 2013 review noted that "nicotine is only 1 of more than 4000 compounds to which the fetus is exposed through maternal smoking. Of these, ∼30 compounds have been associated with adverse health outcomes. Although the exact mechanisms by which nicotine produces adverse fetal effects are unknown, it is likely that hypoxia, undernourishment of the fetus, and direct vasoconstrictor effects on the placental and umbilical vessels all play a role. Nicotine also has been shown to have significant deleterious effects on brain development, including alterations in brain metabolism and neurotransmitter systems and abnormal brain development." It also notes that "abnormalities of newborn neurobehavior, including impaired orientation and autonomic regulation and abnormalities of muscle tone, have been identified in a number of prenatal nicotine exposure studies" and that there is weak data associating fetal nicotine exposure with newborn facial clefts, and that there is no good evidence for newborns suffering nicotine withdrawal from fetal exposure to nicotine.[72]Effective April 1, 1990, the Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) of the California Environmental Protection Agency added nicotine to the list of chemicals known to cause developmental toxicity.[73]

Nicotine is not safe to use in any amount during pregnancy.[74] Questions exist regarding nicotine use during pregnancy and their potential consequences on fetal growth and mortality.[47] Nicotine negatively affects pregnancy outcomes and fetal brain development.[21] Risks to the child later in life via nicotine exposure during pregnancy include type 2 diabetes, obesity, hypertension, neurobehavioral defects, respiratory dysfunction, and infertility.[22] Nicotine crosses the placenta and is found in the breast milk of mothers who smoke as well as mothers who inhale passive smoke.[75]

Reinforcement disorders

Nicotine dependence involves aspects of both psychological dependence and physical dependence, since discontinuation of extended use has been shown to produce both affective (e.g., anxiety, irritability, craving, anhedonia) and somatic (mild motor dysfunctions such as tremor) withdrawal symptoms.[1] Withdrawal symptoms peak in the first day or two[76] and can persist for several weeks.[77] Nicotine has clinically significant cognitive-enhancing effects at low doses, particularly in fine motor skills, attention, and memory. These beneficial cognitive effects may play a role in the maintenance of tobacco dependence.[77]Nicotine is highly addictive,[13][14][78] comparable to heroin or cocaine.[20] Nicotine activates the mesolimbic pathway and induces long-term ΔFosB expression in the nucleus accumbens when inhaled or injected at sufficiently high doses, but not necessarily when ingested.[79][80][81] Consequently, repeated daily exposure (possibly excluding oral route) to nicotine can result in accumbal ΔFosB overexpression, in turn causing nicotine addiction.[79][80]

In dependent smokers, smoking during withdrawal returns cognitive abilities to pre-withdrawal levels, but chronic use may not offer cognitive benefits over not smoking.[21][82]

Use of other drugs

In animals it is relatively simple to determine if consumption of a certain drug increases the later attraction of another drug. In humans, where such direct experiments are not possible, longitudinal studies can show if the probability of a substance use is related to earlier use of other substances.[83]In mice nicotine increased the probability of later consumption of cocaine and the experiments permitted concrete conclusions on the underlying molecular biological alteration in the brain.[84] The biological changes in mice correspond to the epidemiological observations in humans that nicotine consumption is coupled to an increased probability of later use of cannabis and cocaine.[85]

In rats cannabis consumption – earlier in life – increased the later self-administration of nicotine.[86] A study of drug use of 14,577 US 12th graders showed that alcohol consumption was associated with an increased probability of later use of tobacco, cannabis, and other illegal drugs.[87]

Overdose

Nicotine is regarded as a potentially lethal poison.[88] The LD50 of nicotine is 50 mg/kg for rats and 3 mg/kg for mice. 30–60 mg (0.5–1.0 mg/kg) can be a lethal dosage for adult humans.[15][89] However, the widely used human LD50 estimate of 0.5–1.0 mg/kg was questioned in a 2013 review, in light of several documented cases of humans surviving much higher doses; the 2013 review suggests that the lower limit causing fatal outcomes is 500–1000 mg of ingested nicotine, corresponding to 6.5–13 mg/kg orally.[17] Nevertheless, nicotine has a relatively high toxicity in comparison to many other alkaloids such as caffeine, which has an LD50 of 127 mg/kg when administered to mice.[90]At high-enough doses, it is associated with nicotine poisoning.[21] Today nicotine is less commonly used in agricultural insecticides, which was a main source of poisoning. More recent cases of poisoning typically appear to be in the form of Green Tobacco Sickness or due to accidental ingestion of tobacco or tobacco products or ingestion of nicotine-containing plants.[91][92][93] People who harvest or cultivate tobacco may experience Green Tobacco Sickness (GTS), a type of nicotine poisoning caused by dermal exposure to wet tobacco leaves. This occurs most commonly in young, inexperienced tobacco harvesters who do not consume tobacco.[91][94] People can be exposed to nicotine in the workplace by breathing it in, skin absorption, swallowing it, or eye contact. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has set the legal limit (permissible exposure limit) for nicotine exposure in the workplace as 0.5 mg/m3 skin exposure over an 8-hour workday. The US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has set a recommended exposure limit (REL) of 0.5 mg/m3 skin exposure over an 8-hour workday. At environmental levels of 5 mg/m3, nicotine is immediately dangerous to life and health.[95]

It is unlikely that a person would overdose on nicotine through smoking alone. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) stated in 2013 that "There are no significant safety concerns associated with using more than one OTC NRT at the same time, or using an OTC NRT at the same time as another nicotine-containing product—including a cigarette."[96]

The rise in the use of electronic cigarettes, many forms of which are designed to be refilled with nicotine-containing e-liquid supplied in small plastic bottles, has raised concerns over nicotine overdoses, especially in the possibility of young children ingesting the liquids.[24] A 2015 Public Health England report noted an "unconfirmed newspaper report of a fatal poisoning of a two-year old child" and two published case reports of children of similar age who had recovered after ingesting e-liquid and vomiting.[24] They also noted case reports of suicides by nicotine.[24] Where adults drank liquid containing up to 1,500 mg of nicotine they recovered (helped by vomiting), but an ingestion apparently of about 10,000 mg was fatal, as was an injection.[24] They commented that "Serious nicotine poisoning seems normally prevented by the fact that relatively low doses of nicotine cause nausea and vomiting, which stops users from further intake."[24]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Nicotine acts as a receptor agonist at most nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs),[4][5] except at two nicotinic receptor subunits (nAChRα9 and nAChRα10) where it acts as a receptor antagonist.[4]Central nervous system

Effect of nicotine on dopaminergic neurons.

By binding to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the brain, nicotine elicits its psychoactive effects and increases the levels of several neurotransmitters in various brain structures – acting as a sort of "volume control."[medical citation needed] Nicotine has a higher affinity for nicotinic receptors in the brain than those in skeletal muscle, though at toxic doses it can induce contractions and respiratory paralysis.[97] Nicotine's selectivity is thought to be due to a particular amino acid difference on these receptor subtypes.[98]

Nicotine activates nicotinic receptors (particularly α4β2 nicotinic receptors) on neurons that innervate the ventral tegmental area and within the mesolimbic pathway where it appears to cause the release of dopamine.[99][100] This nicotine-induced dopamine release occurs at least partially through activation of the cholinergic–dopaminergic reward link in the ventral tegmental area.[100] Nicotine also appears to induce the release of endogenous opioids that activate opioid pathways in the reward system, since naltrexone – an opioid receptor antagonist – blocks nicotine self-administration.[99] These actions are largely responsible for the strongly reinforcing effects of nicotine, which often occur in the absence of euphoria;[99] however, mild euphoria from nicotine use can occur in some individuals.[99] Chronic nicotine use inhibits class I and II histone deacetylases in the striatum, where this effect plays a role in nicotine addiction.[101][102]

Sympathetic nervous system

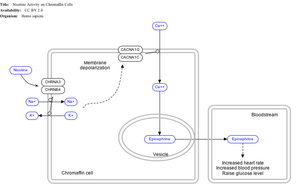

Effect of nicotine on chromaffin cells.

Nicotine also activates the sympathetic nervous system,[103] acting via splanchnic nerves to the adrenal medulla, stimulating the release of epinephrine. Acetylcholine released by preganglionic sympathetic fibers of these nerves acts on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, causing the release of epinephrine (and norepinephrine) into the bloodstream.

Adrenal medulla

By binding to ganglion type nicotinic receptors in the adrenal medulla, nicotine increases flow of adrenaline (epinephrine), a stimulating hormone and neurotransmitter. By binding to the receptors, it causes cell depolarization and an influx of calcium through voltage-gated calcium channels. Calcium triggers the exocytosis of chromaffin granules and thus the release of epinephrine (and norepinephrine) into the bloodstream. The release of epinephrine (adrenaline) causes an increase in heart rate, blood pressure and respiration, as well as higher blood glucose levels.[104]Pharmacokinetics

Urinary metabolites of nicotine, quantified as average percentage of total urinary nicotine.[105]

As nicotine enters the body, it is distributed quickly through the bloodstream and crosses the blood–brain barrier reaching the brain within 10–20 seconds after inhalation.[106] The elimination half-life of nicotine in the body is around two hours.[107]

The amount of nicotine absorbed by the body from smoking can depend on many factors, including the types of tobacco, whether the smoke is inhaled, and whether a filter is used. However, it has been found that the nicotine yield of individual products has only a small effect (4.4%) on the blood concentration of nicotine,[108] suggesting "the assumed health advantage of switching to lower-tar and lower-nicotine cigarettes may be largely offset by the tendency of smokers to compensate by increasing inhalation".

Nicotine has a half-life of 1–2 hours. Cotinine is an active metabolite of nicotine that remains in the blood with a half-life of 18–20 hours, making it easier to analyze.[109]

Nicotine is metabolized in the liver by cytochrome P450 enzymes (mostly CYP2A6, and also by CYP2B6) and FMO3, which selectively metabolizes (S)-nicotine. A major metabolite is cotinine. Other primary metabolites include nicotine N'-oxide, nornicotine, nicotine isomethonium ion, 2-hydroxynicotine and nicotine glucuronide.[110] Under some conditions, other substances may be formed such as myosmine.[111]

Glucuronidation and oxidative metabolism of nicotine to cotinine are both inhibited by menthol, an additive to mentholated cigarettes, thus increasing the half-life of nicotine in vivo.[112]

Chemistry

| NFPA 704 fire diamond |

|---|

| The fire diamond hazard sign for nicotine.[113] |

Nicotine is a hygroscopic, colorless to yellow-brown, oily liquid, that is readily soluble in alcohol, ether or light petroleum. It is miscible with water in its base form between 60 °C and 210 °C. As a nitrogenous base, nicotine forms salts with acids that are usually solid and water-soluble. Its flash point is 95 °C and its auto-ignition temperature is 244 °C.[114]

Nicotine is readily volatile (vapor pressure 5.5 ㎩ at 25 ℃) and dibasic (Kb1 = 1×10⁻⁶, Kb2 = 1×10⁻¹¹).[6]

Nicotine is optically active, having two enantiomeric forms. The naturally occurring form of nicotine is levorotatory with a specific rotation of [α]D = –166.4° ((−)-nicotine). The dextrorotatory form, (+)-nicotine is physiologically less active than (−)-nicotine. (−)-nicotine is more toxic than (+)-nicotine.[115] The salts of (+)-nicotine are usually dextrorotatory. The hydrochloride and sulphate salts become optically inactive if heated in a closed vessel above 180 °C.[116]

On exposure to ultraviolet light or various oxidizing agents, nicotine is converted to nicotine oxide, nicotinic acid (vitamin B3), and methylamine.[116]

Occurrence and biosynthesis

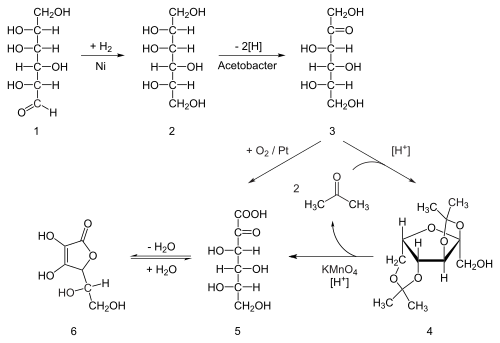

Nicotine biosynthesis

Nicotine is a natural product of tobacco, occurring in the leaves in a range of 0.5 to 7.5% depending on variety.[117] Nicotine also naturally occurs in smaller amounts in plants from the family Solanaceae (such as potatoes, tomatoes, and eggplant).[9]

The biosynthetic pathway of nicotine involves a coupling reaction between the two cyclic structures that compose nicotine. Metabolic studies show that the pyridine ring of nicotine is derived from niacin (nicotinic acid) while the pyrrolidone is derived from N-methyl-Δ1-pyrrollidium cation.[118][119] Biosynthesis of the two component structures proceeds via two independent syntheses, the NAD pathway for niacin and the tropane pathway for N-methyl-Δ1-pyrrollidium cation.

The NAD pathway in the genus nicotiana begins with the oxidation of aspartic acid into α-imino succinate by aspartate oxidase (AO). This is followed by a condensation with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate and a cyclization catalyzed by quinolinate synthase (QS) to give quinolinic acid. Quinolinic acid then reacts with phosphoriboxyl pyrophosphate catalyzed by quinolinic acid phosphoribosyl transferase (QPT) to form niacin mononucleotide (NaMN). The reaction now proceeds via the NAD salvage cycle to produce niacin via the conversion of nicotinamide by the enzyme nicotinamidase.[citation needed]

The N-methyl-Δ1-pyrrollidium cation used in the synthesis of nicotine is an intermediate in the synthesis of tropane-derived alkaloids. Biosynthesis begins with decarboxylation of ornithine by ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) to produce putrescine. Putrescine is then converted into N-methyl putrescine via methylation by SAM catalyzed by putrescine N-methyltransferase (PMT). N-methylputrescine then undergoes deamination into 4-methylaminobutanal by the N-methylputrescine oxidase (MPO) enzyme, 4-methylaminobutanal then spontaneously cyclize into N-methyl-Δ1-pyrrollidium cation.[citation needed]

The final step in the synthesis of nicotine is the coupling between N-methyl-Δ1-pyrrollidium cation and niacin. Although studies conclude some form of coupling between the two component structures, the definite process and mechanism remains undetermined. The current agreed theory involves the conversion of niacin into 2,5-dihydropyridine through 3,6-dihydronicotinic acid. The 2,5-dihydropyridine intermediate would then react with N-methyl-Δ1-pyrrollidium cation to form enantiomerically pure (−)-nicotine.[120]

Detection in body fluids

Nicotine can be quantified in blood, plasma, or urine to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning or to facilitate a forensic autopsy. Urinary or salivary cotinine concentrations are frequently measured for the purposes of pre-employment and health insurance medical screening programs. Careful interpretation of results is important, since passive exposure to cigarette smoke can result in significant accumulation of nicotine, followed by the appearance of its metabolites in various body fluids.[121][122] Nicotine use is not regulated in competitive sports programs.[123]History

Nicotine is named after the tobacco plant Nicotiana tabacum, which in turn is named after the French ambassador in Portugal, Jean Nicot de Villemain, who sent tobacco and seeds to Paris in 1560, presented to the French King,[124] and who promoted their medicinal use. Smoking was believed to protect against illness, particularly the plague.[124]Tobacco was introduced to Europe in 1559, and by the late 17th century, it was used not only for smoking but also as an insecticide. After World War II, over 2,500 tons of nicotine insecticide were used worldwide, but by the 1980s the use of nicotine insecticide had declined below 200 tons. This was due to the availability of other insecticides that are cheaper and less harmful to mammals.[12]

Currently, nicotine, even in the form of tobacco dust, is prohibited as a pesticide for organic farming in the United States.[125][126]

In 2008, the EPA received a request, from the registrant, to cancel the registration of the last nicotine pesticide registered in the United States.[127] This request was granted, and since 1 January 2014, this pesticide has not been available for sale.[128]

Chemical identification

Nicotine was first isolated from the tobacco plant in 1828 by physician Wilhelm Heinrich Posselt and chemist Karl Ludwig Reimann of Germany, who considered it a poison.[129][130] Its chemical empirical formula was described by Melsens in 1843,[131] its structure was discovered by Adolf Pinner and Richard Wolffenstein in 1893,[132][133][134][clarification needed] and it was first synthesized by Amé Pictet and A. Rotschy in 1904.[135]Society and culture

The nicotine content of popular American-brand cigarettes has increased over time, and one study found that there was an average increase of 1.78% per year between the years of 1998 and 2005.[136]Research

While acute/initial nicotine intake causes activation of nicotine receptors, chronic low doses of nicotine use leads to desensitisation of nicotine receptors (due to the development of tolerance) and results in an antidepressant effect, with early research showing low dose nicotine patches could be an effective treatment of major depressive disorder in non-smokers.[137] However, the original research concluded that: "Nicotine patches produced short-term improvement of depression with minor side effects. Because of nicotine's high risk to health, nicotine patches are not recommended for clinical use in depression."[138]Though tobacco smoking is associated with an increased risk of Alzheimer's disease,[139] there is evidence that nicotine itself has the potential to prevent and treat Alzheimer's disease.[140]

Research into nicotine's most predominant metabolite, cotinine, suggests that some of nicotine's psychoactive effects are mediated by cotinine.[141][142]

Little research is available in humans but animal research suggests there is potential benefit from nicotine in Parkinson's disease.[143]