The Thirteenth Amendment (Amendment XIII) to the United States Constitution abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime. In Congress, it was passed by the Senate on April 8, 1864, and by the House on January 31, 1865. The amendment was ratified by the required number of states on December 6, 1865. On December 18, 1865, Secretary of State William H. Seward proclaimed its adoption. It was the first of the three Reconstruction Amendments adopted following the American Civil War.

Since the American Revolution, states had divided into states that allowed or states that prohibited slavery. Slavery was implicitly permitted in the original Constitution through provisions such as Article I, Section 2, Clause 3, commonly known as the Three-Fifths Compromise, which detailed how each slave state's enslaved population would be factored into its total population count for the purposes of apportioning seats in the United States House of Representatives and direct taxes among the states. Though many slaves had been declared free by President Abraham Lincoln's 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, their post-war status was uncertain. On April 8, 1864, the Senate passed an amendment to abolish slavery. After one unsuccessful vote and extensive legislative maneuvering by the Lincoln administration, the House followed suit on January 31, 1865. The measure was swiftly ratified by nearly all Northern states, along with a sufficient number of border states up to the death of Lincoln, but approval came with President Andrew Johnson, who encouraged the "reconstructed" Southern states of Alabama, North Carolina and Georgia to agree as 27 states, and cause it to be adopted before the end of 1865.

Though the amendment formally abolished slavery throughout the United States, factors such as Black Codes, white supremacist violence, and selective enforcement of statutes continued to subject some black Americans to involuntary labor, particularly in the South. In contrast to the other Reconstruction Amendments, the Thirteenth Amendment was rarely cited in later case law, but has been used to strike down peonage and some race-based discrimination as "badges and incidents of slavery". The Thirteenth Amendment applies to the actions of private citizens, while the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments apply only to state actors. The Thirteenth Amendment also enables Congress to pass laws against sex trafficking and other modern forms of slavery.

Text

Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

Slavery in the United States

Slavery existed in all of the original thirteen British North American colonies. Prior to the Thirteenth Amendment, the United States Constitution did not expressly use the words slave or slavery but included several provisions about unfree persons. The Three-Fifths Compromise, Article I, Section 2, Clause 3 of the Constitution, allocated Congressional representation based "on the whole Number of free Persons" and "three fifths of all other Persons". This clause was a compromise between Southerners who wished slaves to be counted as 'persons' for congressional representation and northerners rejecting these out of concern of too much power for the South, because representation in the new Congress would be based on population in contrast to the one-vote-for-one-state principle in the earlier Continental Congress. Under the Fugitive Slave Clause, Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3, "No person held to Service or Labour in one State" would be freed by escaping to another. Article I, Section 9, Clause 1 allowed Congress to pass legislation outlawing the "Importation of Persons", but not until 1808. However, for purposes of the Fifth Amendment—which states that, "No person shall... be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law"—slaves were understood as property. Although abolitionists used the Fifth Amendment to argue against slavery, it became part of the legal basis in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) for treating slaves as property.

Stimulated by the philosophy of the Declaration of Independence, between 1777 and 1804 every Northern state provided for the immediate or gradual abolition of slavery. Most of the slaves involved were household servants. No Southern state did so, and the slave population of the South continued to grow, peaking at almost 4 million people in 1861. An abolitionist movement headed by such figures as William Lloyd Garrison grew in strength in the North, calling for the end of slavery nationwide and exacerbating tensions between North and South. The American Colonization Society, an alliance between abolitionists who felt the races should be kept separated and slaveholders who feared the presence of freed blacks would encourage slave rebellions, called for the emigration and colonization of both free blacks and slaves to Africa. Its views were endorsed by politicians such as Henry Clay, who feared that the main abolitionist movement would provoke a civil war. Proposals to eliminate slavery by constitutional amendment were introduced by Representative Arthur Livermore in 1818 and by John Quincy Adams in 1839, but failed to gain significant traction.

As the country continued to expand, the issue of slavery in its new territories became the dominant national issue. The Southern position was that slaves were property and therefore could be moved to the territories like all other forms of property. The 1820 Missouri Compromise provided for the admission of Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state, preserving the Senate's equality between the regions. In 1846, the Wilmot Proviso was introduced to a war appropriations bill to ban slavery in all territories acquired in the Mexican–American War; the Proviso repeatedly passed the House, but not the Senate. The Compromise of 1850 temporarily defused the issue by admitting California as a free state, instituting a stronger Fugitive Slave Act, banning the slave trade in Washington, D.C., and allowing New Mexico and Utah self-determination on the slavery issue.

Despite the compromise, tensions between North and South continued to rise over the subsequent decade, inflamed by, amongst other things, the publication of the 1852 anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom's Cabin; fighting between pro-slavery and abolitionist forces in Kansas, beginning in 1854; the 1857 Dred Scott decision, which struck down provisions of the Compromise of 1850; abolitionist John Brown's 1859 attempt to start a slave revolt at Harpers Ferry and the 1860 election of slavery critic Abraham Lincoln to the presidency. The Southern states seceded from the Union in the months following Lincoln's election, forming the Confederate States of America, and beginning the American Civil War.

Proposal and ratification

Crafting the amendment

Representative James Mitchell Ashley proposed an amendment abolishing slavery in 1863.

Acting under presidential war powers, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, which proclaimed the freedom of slaves in the ten states that were still in rebellion. However, it did not affect the status of slaves in the border states that had remained loyal to the Union. That December, Lincoln again used his war powers and issued a "Proclamation for Amnesty and Reconstruction", which offered Southern states a chance to peacefully rejoin the Union if they abolished slavery and collected loyalty oaths from 10% of their voting population. Southern states did not readily accept the deal, and the status of slavery remained uncertain.

In the final years of the Civil War, Union lawmakers debated various proposals for Reconstruction. Some of these called for a constitutional amendment to abolish slavery nationally and permanently. On December 14, 1863, a bill proposing such an amendment was introduced by Representative James Mitchell Ashley of Ohio. Representative James F. Wilson of Iowa soon followed with a similar proposal. On January 11, 1864, Senator John B. Henderson of Missouri submitted a joint resolution for a constitutional amendment abolishing slavery. The Senate Judiciary Committee, chaired by Lyman Trumbull of Illinois, became involved in merging different proposals for an amendment.

Radical Republicans led by Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner and Pennsylvania Representative Thaddeus Stevens sought a more expansive version of the amendment. On February 8, 1864, Sumner submitted a constitutional amendment stating:

All persons are equal before the law, so that no person can hold another as a slave; and the Congress shall have power to make all laws necessary and proper to carry this declaration into effect everywhere in the United States.Sumner tried to promote his own more expansive wording by circumventing the Trumbull-controlled Judiciary Committee, but failed. On February 10, the Senate Judiciary Committee presented the Senate with an amendment proposal based on drafts of Ashley, Wilson and Henderson.

The Committee's version used text from the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which stipulates, "There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory, otherwise than in the punishment of crimes whereof the party shall have been duly convicted." Though using Henderson's proposed amendment as the basis for its new draft, the Judiciary Committee removed language that would have allowed a constitutional amendment to be adopted with only a majority vote in each House of Congress and ratification by two-thirds of the states (instead of two-thirds and three-fourths, respectively).

Passage by Congress

The Senate passed the amendment on April 8, 1864, by a vote of 38 to 6; two Democrats, Reverdy Johnson of Maryland and James Nesmith of Oregon voted "aye." However, just over two months later on June 15, the House failed to do so, with 93 in favor and 65 against, thirteen votes short of the two-thirds vote needed for passage; the vote split largely along party lines, with Republicans supporting and Democrats opposing. In the 1864 presidential race, former Free Soil Party candidate John C. Frémont threatened a third-party run opposing Lincoln, this time on a platform endorsing an anti-slavery amendment. The Republican Party platform had, as yet, failed to include a similar plank, though Lincoln endorsed the amendment in a letter accepting his nomination. Fremont withdrew from the race on September 22, 1864 and endorsed Lincoln.With no Southern states represented, few members of Congress pushed moral and religious arguments in favor of slavery. Democrats who opposed the amendment generally made arguments based on federalism and states' rights. Some argued that the proposed change so violated the spirit of the Constitution that it would not be a valid "amendment" but would instead constitute "revolution". Representative White, among other opponents, warned that the amendment would lead to full citizenship for blacks.

Republicans portrayed slavery as uncivilized and argued for abolition as a necessary step in national progress. Amendment supporters also argued that the slave system had negative effects on white people. These included the lower wages resulting from competition with forced labor, as well as repression of abolitionist whites in the South. Advocates said ending slavery would restore the First Amendment and other constitutional rights violated by censorship and intimidation in slave states.

White, Northern Republicans and some Democrats became excited about an abolition amendment, holding meetings and issuing resolutions. Many blacks though, particularly in the South, focused more on land ownership and education as the key to liberation. As slavery began to seem politically untenable, an array of Northern Democrats successively announced their support for the amendment, including Representative James Brooks, Senator Reverdy Johnson, and Tammany Hall, a powerful New York political machine.

Celebration erupts after the amendment is passed by the House of Representatives.

President Lincoln had had concerns that the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 might be reversed or found invalid by the judiciary after the war. He saw constitutional amendment as a more permanent solution. He had remained outwardly neutral on the amendment because he considered it politically too dangerous. Nonetheless, Lincoln's 1864 party platform resolved to abolish slavery by constitutional amendment. After winning reelection in the election of 1864, Lincoln made the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment his top legislative priority, beginning with his efforts in Congress during its "lame duck" session. Popular support for the amendment mounted and Lincoln urged Congress on in his December 6, 1864 State of the Union Address: "there is only a question of time as to when the proposed amendment will go to the States for their action. And as it is to so go, at all events, may we not agree that the sooner the better?"

Lincoln instructed Secretary of State William H. Seward, Representative John B. Alley and others to procure votes by any means necessary, and they promised government posts and campaign contributions to outgoing Democrats willing to switch sides. Seward had a large fund for direct bribes. Ashley, who reintroduced the measure into the House, also lobbied several Democrats to vote in favor of the measure. Representative Thaddeus Stevens later commented that "the greatest measure of the nineteenth century was passed by corruption aided and abetted by the purest man in America"; however, Lincoln's precise role in making deals for votes remains unknown.

Republicans in Congress claimed a mandate for abolition, having gained in the elections for Senate and House. The 1864 Democratic vice-presidential nominee, Representative George H. Pendleton, led opposition to the measure. Republicans toned down their language of radical equality in order to broaden the amendment's coalition of supporters. In order to reassure critics worried that the amendment would tear apart the social fabric, some Republicans explicitly promised that the amendment would leave patriarchy intact.

In mid-January 1865, Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax estimated the amendment to be five votes short of passage. Ashley postponed the vote. At this point, Lincoln intensified his push for the amendment, making direct emotional appeals to particular members of Congress. On January 31, 1865, the House called another vote on the amendment, with neither side being certain of the outcome. With 183 House members present, 122 would have to vote "aye" to secure passage of the resolution; however eight members abstained, reducing the number to 117. Every Republican supported the measure, as well as 16 Democrats, almost all of them lame ducks. The amendment finally passed by a vote of 119 to 56, narrowly reaching the required two-thirds majority. The House exploded into celebration, with some members openly weeping. Black onlookers, who had only been allowed to attend Congressional sessions since the previous year, cheered from the galleries.

While the Constitution does not provide the President any formal role in the amendment process, the joint resolution was sent to Lincoln for his signature. Under the usual signatures of the Speaker of the House and the President of the Senate, President Lincoln wrote the word "Approved" and added his signature to the joint resolution on February 1, 1865. On February 7, Congress passed a resolution affirming that the Presidential signature was unnecessary. The Thirteenth Amendment is the only ratified amendment signed by a President, although James Buchanan had signed the Corwin Amendment that the 36th Congress had adopted and sent to the states in March 1861.

Ratification by the states

Ratified amendment, 1865

Ratified amendment post-enactment, 1865–1870

Ratified amendment after first rejecting amendment, 1866–1995

Territories of the United States in 1865, not yet states

When the Thirteenth Amendment was submitted to the states on February 1, 1865, it was quickly taken up by several legislatures. By the end of the month, it had been ratified by eighteen states. Among them were the ex-Confederate states of Virginia and Louisiana, where ratifications were submitted by Reconstruction governments. These, along with subsequent ratifications from Arkansas and Tennessee raised the issues of how many seceded states had legally valid legislatures; and if there were fewer legislatures than states, if Article V required ratification by three-fourths of the states or three-fourths of the legally valid state legislatures. President Lincoln in his last speech, on April 11, 1865, called the question about whether the Southern states were in or out of the Union a "pernicious abstraction." Obviously, he declared, they were not "in their proper practical relation with the Union"; whence everyone's object should be to restore that relation. Lincoln was assassinated three days later.

With Congress out of session, the new President, Andrew Johnson, began a period known as "Presidential Reconstruction", in which he personally oversaw the creation of new state governments throughout the South. He oversaw the convening of state political conventions populated by delegates whom he deemed to be loyal. Three leading issues came before the conventions: secession itself, the abolition of slavery, and the Confederate war debt. Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, and South Carolina held conventions in 1865, while Texas' convention did not organize until March 1866. Johnson hoped to prevent deliberation over whether to re-admit the Southern states by accomplishing full ratification before Congress reconvened in December. He believed he could silence those who wished to deny the Southern states their place in the Union by pointing to how essential their assent had been to the successful ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment.

Direct negotiations between state governments and the Johnson administration ensued. As the summer wore on, administration officials began including assurances of the measure's limited scope with their demands for ratification. Johnson himself suggested directly to the governors of Mississippi and North Carolina that they could proactively control the allocation of rights to freedmen. Though Johnson obviously expected the freed people to enjoy at least some civil rights, including, as he specified, the right to testify in court, he wanted state lawmakers to know that the power to confer such rights would remain with the states. When South Carolina provisional governor Benjamin Franklin Perry objected to the scope of the amendment's enforcement clause, Secretary of State Seward responded by telegraph that in fact the second clause "is really restraining in its effect, instead of enlarging the powers of Congress". White politicians throughout the South were concerned that Congress might cite the amendment's enforcement powers as a way to authorize black suffrage.

When South Carolina ratified the amendment in November 1865, it issued its own interpretive declaration that "any attempt by Congress toward legislating upon the political status of former slaves, or their civil relations, would be contrary to the Constitution of the United States". Alabama and Louisiana also declared that their ratification did not imply federal power to legislate on the status of former slaves. During the first week of December, North Carolina and Georgia gave the amendment the final votes needed for it to become part of the Constitution.

The Thirteenth Amendment became part of the Constitution on December 6, 1865, based on the following ratifications:

- Illinois — February 1, 1865

- Rhode Island — February 2, 1865

- Michigan — February 3, 1865

- Maryland — February 3, 1865

- New York — February 3, 1865

- Pennsylvania — February 3, 1865

- West Virginia — February 3, 1865

- Missouri — February 6, 1865

- Maine — February 7, 1865

- Kansas — February 7, 1865

- Massachusetts — February 7, 1865

- Virginia — February 9, 1865

- Ohio — February 10, 1865

- Indiana — February 13, 1865

- Nevada — February 16, 1865

- Louisiana — February 17, 1865

- Minnesota — February 23, 1865

- Wisconsin — February 24, 1865

- Vermont — March 9, 1865

- Tennessee — April 7, 1865

- Arkansas — April 14, 1865

- Connecticut — May 4, 1865

- New Hampshire — July 1, 1865

- South Carolina — November 13, 1865

- Alabama — December 2, 1865

- North Carolina — December 4, 1865

- Georgia — December 6, 1865

The Thirteenth Amendment was subsequently ratified by:

- Oregon — December 8, 1865

- California — December 19, 1865

- Florida — December 28, 1865 (reaffirmed – June 9, 1868)

- Iowa — January 15, 1866

- New Jersey — January 23, 1866 (after rejection – March 16, 1865)

- Texas — February 18, 1870

- Delaware — February 12, 1901 (after rejection – February 8, 1865)

- Kentucky — March 18, 1976 (after rejection – February 24, 1865)

- Mississippi — March 16, 1995; Certified – February 7, 2013 (after rejection – December 5, 1865)

Effects

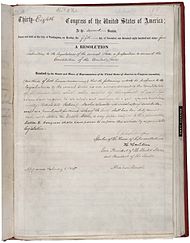

Amendment XIII in the National Archives, bearing the signature of Abraham Lincoln

The impact of the abolition of slavery was felt quickly. When the Thirteenth Amendment became operational, the scope of Lincoln's 1863 Emancipation Proclamation was widened to include the entire nation. Although the majority of Kentucky's slaves had been emancipated, 65,000–100,000 people remained to be legally freed when the Amendment went into effect on December 18.[83][84] In Delaware, where a large number of slaves had escaped during the war, nine hundred people became legally free.

In addition to abolishing slavery and prohibiting involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime, the Thirteenth Amendment also nullified the Fugitive Slave Clause and the Three-Fifths Compromise. The population of a state originally included (for congressional apportionment purposes) all "free persons", three-fifths of "other persons" (i.e., slaves) and excluded untaxed Native Americans. The Three-Fifths Compromise was a provision in the Constitution that required three-fifths of the population of slaves be counted for purposes of apportionment of seats in the House of Representatives and taxes among the states. This compromise had the effect of increasing the political power of slave-holding states by increasing their share of seats in the House of Representatives, and consequently their share in the Electoral College (where a state's influence over the election of the President is tied to the size of its congressional delegation).

Even as the Thirteenth Amendment was working its way through the ratification process, Republicans in Congress grew increasingly concerned about the potential for there to be a large increase in the congressional representation of the Democratic-dominated Southern states. Because the full population of freed slaves would be counted rather than three-fifths, the Southern states would dramatically increase their power in the population-based House of Representatives. Republicans hoped to offset this advantage by attracting and protecting votes of the newly enfranchised black population.

Political and economic change in the South

Southern culture remained deeply racist, and those blacks who remained faced a dangerous situation. J. J. Gries reported to the Joint Committee on Reconstruction: "There is a kind of innate feeling, a lingering hope among many in the South that slavery will be regalvanized in some shape or other. They tried by their laws to make a worse slavery than there was before, for the freedman has not the protection which the master from interest gave him before." W. E. B. Du Bois wrote in 1935:Slavery was not abolished even after the Thirteenth Amendment. There were four million freedmen and most of them on the same plantation, doing the same work that they did before emancipation, except as their work had been interrupted and changed by the upheaval of war. Moreover, they were getting about the same wages and apparently were going to be subject to slave codes modified only in name. There were among them thousands of fugitives in the camps of the soldiers or on the streets of the cities, homeless, sick, and impoverished. They had been freed practically with no land nor money, and, save in exceptional cases, without legal status, and without protection.Official emancipation did not substantially alter the economic situation of most blacks who remained in the south.

As the amendment still permitted labor as punishment for convicted criminals, Southern states responded with what historian Douglas A. Blackmon called "an array of interlocking laws essentially intended to criminalize black life". These laws, passed or updated after emancipation, were known as Black Codes. Mississippi was the first state to pass such codes, with an 1865 law titled "An Act to confer Civil Rights on Freedmen". The Mississippi law required black workers to contract with white farmers by January 1 of each year or face punishment for vagrancy. Blacks could be sentenced to forced labor for crimes including petty theft, using obscene language, or selling cotton after sunset. States passed new, strict vagrancy laws that were selectively enforced against blacks without white protectors. The labor of these convicts was then sold to farms, factories, lumber camps, quarries, and mines.

After its ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment in November 1865, the South Carolina legislature immediately began to legislate Black Codes. The Black Codes created a separate set of laws, punishments, and acceptable behaviors for anyone with more than one black great-grandparent. Under these Codes, Blacks could only work as farmers or servants and had few Constitutional rights. Restrictions on black land ownership threatened to make economic subservience permanent.

Some states mandated indefinitely long periods of child "apprenticeship". Some laws did not target Blacks specifically, but instead affected farm workers, most of whom were Black. At the same time, many states passed laws to actively prevent Blacks from acquiring property.

Congressional and executive enforcement

As its first enforcement legislation, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1866, guaranteeing black Americans citizenship and equal protection of the law, though not the right to vote. The amendment was also used as authorizing several Freedmen's Bureau bills. President Andrew Johnson vetoed these bills, but Congress overrode his vetoes to pass the Civil Rights Act and the Second Freedmen's Bureau Bill.Proponents of the Act, including Trumbull and Wilson, argued that Section 2 of the Thirteenth Amendment authorized the federal government to legislate civil rights for the States. Others disagreed, maintaining that inequality conditions were distinct from slavery. Seeking more substantial justification, and fearing that future opponents would again seek to overturn the legislation, Congress and the states added additional protections to the Constitution: the Fourteenth Amendment (1868) defining citizenship and mandating equal protection under the law, and the Fifteenth Amendment (1870) banning racial voting restrictions.

The Freedmen's Bureau enforced the amendment locally, providing a degree of support for people subject to the Black Codes. Reciprocally, the Thirteenth Amendment established the Bureau's legal basis to operate in Kentucky. The Civil Rights Act circumvented racism in local jurisdictions by allowing blacks access to the federal courts. The Enforcement Acts of 1870–1871 and the Civil Rights Act of 1875, in combating the violence and intimidation of white supremacy, were also part of the effort to end slave conditions for Southern blacks. However, the effect of these laws waned as political will diminished and the federal government lost authority in the South, particularly after the Compromise of 1877 ended Reconstruction in exchange for a Republican presidency.

Peonage law

Southern business owners sought to reproduce the profitable arrangement of slavery with a system called peonage, in which disproportionately black workers were entrapped by loans and compelled to work indefinitely due to the resulting debt. Peonage continued well through Reconstruction and ensnared a large proportion of black workers in the South. These workers remained destitute and persecuted, forced to work dangerous jobs and further confined legally by the racist Jim Crow laws that governed the South. Peonage differed from chattel slavery because it was not strictly hereditary and did not allow the sale of people in exactly the same fashion. However, a person's debt—and by extension a person—could still be sold, and the system resembled antebellum slavery in many ways.With the Peonage Act of 1867, Congress abolished "the holding of any person to service or labor under the system known as peonage", specifically banning "the voluntary or involuntary service or labor of any persons as peons, in liquidation of any debt or obligation, or otherwise."

In 1939, the Department of Justice created the Civil Rights Section, which focused primarily on First Amendment and labor rights. The increasing scrutiny of totalitarianism in the lead-up to World War II brought increased attention to issues of slavery and involuntary servitude, abroad and at home. The U.S. sought to counter foreign propaganda and increase its credibility on the race issue by combatting the Southern peonage system. Under the leadership of Attorney General Francis Biddle, the Civil Rights Section invoked the constitutional amendments and legislation of the Reconstruction Era as the basis for its actions.

In 1947, the DOJ successfully prosecuted Elizabeth Ingalls for keeping domestic servant Dora L. Jones in conditions of slavery. The court found that Jones "was a person wholly subject to the will of defendant; that she was one who had no freedom of action and whose person and services were wholly under the control of defendant and who was in a state of enforced compulsory service to the defendant." The Thirteenth Amendment enjoyed a swell of attention during this period, but from Brown v. Board of Education (1954) until Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co. (1968) it was again eclipsed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

Penal labor exemption

The Thirteenth Amendment exempts penal labor from its prohibition of forced labor. This allows prisoners who have been convicted of crimes (not those merely awaiting trial) to be required to perform labor or else face punishment while in custody.Few records of the committee's deliberations during the drafting of the Thirteenth Amendment survived, and the debate in both Congress and the state legislatures that followed featured almost no discussion of this provision. It was apparently considered noncontroversial at the time, or at least legislators gave it little thought. The drafters based the amendment's phrasing on the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which features an identical exception. Thomas Jefferson authored an early version of that ordinance's anti-slavery clause, including the exception of punishment for a crime, and also sought to prohibit slavery in general after 1800. Jefferson was an admirer of the works of Italian criminologist Cesare Beccaria. Beccaria's On Crimes and Punishments suggested that the death penalty should be abolished and replaced with a lifetime of enslavement for the worst criminals; Jefferson likely included the clause due to his agreement with Beccaria. Beccaria, while attempting to reduce "legal barbarism" of the 1700s, considered forced labor one of the few harsh punishments acceptable; for example, he advocated slave labor as a just punishment for robbery, so that the thief's labor could be used to pay recompense to their victims and to society. Penal "hard labor" has ancient origins, and was adopted early in American history (as in Europe) often as a substitute for capital or corporal punishment.

Various commentators have accused states of abusing this provision to re-establish systems similar to slavery, or of otherwise exploiting such labor in a manner unfair to local labor. The Black Codes in the South criminalized "vagrancy", which was largely enforced against freed slaves. Later, convict lease programs in the South allowed local plantations to rent inexpensive prisoner labor. While many of these programs have been phased out (leasing of convicts was forbidden by President Franklin Roosevelt in 1941), prison labor continues in America under a variety of justifications. Prison labor programs vary widely; some are uncompensated prison maintenance tasks, some are for local government maintenance tasks, some are for local businesses, and others are closer to internships. Modern rationales for prison labor programs often include reduction of recidivism and re-acclimation to society; the idea is that such labor programs will make it easier for the prisoner upon release to find gainful employment rather than relapse to criminality. However, this topic is not well-studied, and much of the work offered is so menial as to be unlikely to improve employment prospects. As of 2017, most prison labor programs do compensate prisoners, but generally with very low wages. What wages they do earn are often heavily garnished, with as much as 80% of a prisoner's paycheck withheld in the harshest cases.

Judicial interpretation

In contrast to the other "Reconstruction Amendments", the Thirteenth Amendment was rarely cited in later case law. As historian Amy Dru Stanley summarizes, "beyond a handful of landmark rulings striking down debt peonage, flagrant involuntary servitude, and some instances of race-based violence and discrimination, the Thirteenth Amendment has never been a potent source of rights claims".Black slaves and their descendants

United States v. Rhodes (1866), one of the first Thirteenth Amendment cases, tested the constitutionality of provisions in the Civil Rights Act of 1866 that granted blacks redress in the federal courts. Kentucky law prohibited blacks from testifying against whites—an arrangement which compromised the ability of Nancy Talbot ("a citizen of the United States of the African race") to reach justice against a white person accused of robbing her. After Talbot attempted to try the case in federal court, the Kentucky Supreme Court ruled this federal option unconstitutional. Noah Swayne (a Supreme Court justice sitting on the Kentucky Circuit Court) overturned the Kentucky decision, holding that without the material enforcement provided by the Civil Rights Act, slavery would not truly be abolished. With In Re Turner (1867), Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase ordered freedom for Elizabeth Turner, a former slave in Maryland who became indentured to her former master.In Blyew v. United States, (1872) the Supreme Court heard another Civil Rights Act case relating to federal courts in Kentucky. John Blyew and George Kennard were white men visiting the cabin of a black family, the Fosters. Blyew apparently became angry with sixteen-year-old Richard Foster and hit him twice in the head with an ax. Blyew and Kennard killed Richard's parents, Sallie and Jack Foster, and his blind grandmother, Lucy Armstrong. They severely wounded the Fosters' two young daughters. Kentucky courts would not allow the Foster children to testify against Blyew and Kennard. Federal courts, authorized by the Civil Rights Act, found Blyew and Kennard guilty of murder. The Supreme Court ruled that the Foster children did not have standing in federal courts because only living people could take advantage of the Act. In doing so, the Courts effectively ruled that Thirteenth Amendment did not permit a federal remedy in murder cases. Swayne and Joseph P. Bradley dissented, maintaining that in order to have meaningful effects, the Thirteenth Amendment would have to address systemic racial oppression.

The Blyew case set a precedent in state and federal courts that led to the erosion of Congress's Thirteenth Amendment powers. The Supreme Court continued along this path in the Slaughter-House Cases (1873), which upheld a state-sanctioned monopoly of white butchers. In United States v. Cruikshank (1876), the Court ignored Thirteenth Amendment dicta from a circuit court decision to exonerate perpetrators of the Colfax massacre and invalidate the Enforcement Act of 1870.

John Marshall Harlan became known as "The Great Dissenter" for his minority opinions favoring powerful Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments.

Undoubtedly while negro slavery alone was in the mind of the Congress which proposed the thirteenth article, it forbids any other kind of slavery, now or hereafter. If Mexican peonage or the Chinese coolie labor system shall develop slavery of the Mexican or Chinese race within our territory, this amendment may safely be trusted to make it void. And so if other rights are assailed by the States which properly and necessarily fall within the protection of these articles, that protection will apply, though the party interested may not be of African descent. But what we do say, and what we wish to be understood is, that in any fair and just construction of any section or phrase of these amendments, it is necessary to look to the purpose which we have said was the pervading spirit of them all, the evil which they were designed to remedy, and the process of continued addition to the Constitution, until that purpose was supposed to be accomplished, as far as constitutional law can accomplish it.In the Civil Rights Cases (1883), the Supreme Court reviewed five consolidated cases dealing with the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which outlawed racial discrimination at "inns, public conveyances on land or water, theaters, and other places of public amusement". The Court ruled that the Thirteenth Amendment did not ban most forms of racial discrimination by non-government actors. In the majority decision, Bradley wrote (again in non-binding dicta) that the Thirteenth Amendment empowered Congress to attack "badges and incidents of slavery". However, he distinguished between "fundamental rights" of citizenship, protected by the Thirteenth Amendment, and the "social rights of men and races in the community". The majority opinion held that "it would be running the slavery argument into the ground to make it apply to every act of discrimination which a person may see fit to make as to guests he will entertain, or as to the people he will take into his coach or cab or car; or admit to his concert or theatre, or deal with in other matters of intercourse or business." In his solitary dissent, John Marshall Harlan (a Kentucky lawyer who changed his mind about civil rights law after witnessing organized racist violence) argued that "such discrimination practiced by corporations and individuals in the exercise of their public or quasi-public functions is a badge of servitude, the imposition of which congress may prevent under its power."

The Court in the Civil Rights Cases also held that appropriate legislation under the amendment could go beyond nullifying state laws establishing or upholding slavery, because the amendment "has a reflex character also, establishing and decreeing universal civil and political freedom throughout the United States" and thus Congress was empowered "to pass all laws necessary and proper for abolishing all badges and incidents of slavery in the United States." The Court stated about the scope the amendment:

This amendment, as well as the Fourteenth, is undoubtedly self-executing, without any ancillary legislation, so far as its terms are applicable to any existing state of circumstances. By its own unaided force and effect, it abolished slavery and established universal freedom. Still, legislation may be necessary and proper to meet all the various cases and circumstances to be affected by it, and to prescribe proper modes of redress for its violation in letter or spirit. And such legislation may be primary and direct in its character, for the amendment is not a mere prohibition of State laws establishing or upholding slavery, but an absolute declaration that slavery or involuntary servitude shall not exist in any part of the United States.Attorneys in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) argued that racial segregation involved "observances of a servile character coincident with the incidents of slavery", in violation of the Thirteenth Amendment. In their brief to the Supreme Court, Plessy's lawyers wrote that "distinction of race and caste" was inherently unconstitutional. The Supreme Court rejected this reasoning and upheld state laws enforcing segregation under the "separate but equal" doctrine. In the (7–1) majority decision, the Court found that "a statute which implies merely a legal distinction between the white and colored races—a distinction which is founded on the color of the two races and which must always exist so long as white men are distinguished from the other race by color—has no tendency to destroy the legal equality of the two races, or reestablish a state of involuntary servitude." Harlan dissented, writing: "The thin disguise of 'equal' accommodations for passengers in railroad coaches will not mislead any one, nor, atone for the wrong this day done."

In Hodges v. United States (1906), the Court struck down a federal statute providing for the punishment of two or more people who "conspire to injure, oppress, threaten or intimidate any citizen in the free exercise or enjoyment of any right or privilege secured to him by the Constitution or laws of the United States". A group of white men in Arkansas conspired to violently prevent eight black workers from performing their jobs at a lumber mill; the group was convicted by a federal grand jury. The Supreme Court ruled that the federal statute, which outlawed conspiracies to deprive citizens of their liberty, was not authorized by the Thirteenth Amendment. It held that "no mere personal assault or trespass or appropriation operates to reduce the individual to a condition of slavery". Harlan dissented, maintaining his opinion that the Thirteenth Amendment should protect freedom beyond "physical restraint".[151] Corrigan v. Buckley (1922) reaffirmed the interpretation from Hodges, finding that the amendment does not apply to restrictive covenants.

Enforcement of federal civil rights law in the South created numerous peonage cases, which slowly traveled up through the judiciary. The Supreme Court ruled in Clyatt v. United States (1905) that peonage was involuntary servitude. It held that although employers sometimes described their workers' entry into contract as voluntary, the servitude of peonage was always (by definition) involuntary.

In Bailey v. Alabama the U.S. Supreme Court again reaffirmed its holding that Thirteenth Amendment was not solely a ban on chattel slavery, but also covers a much broader array of labor arrangements and social deprivations In addition to the aforesaid the Court also ruled on Congress enforcement power under the Thirteenth Amendment. The Court said:

The plain intention [of the amendment] was to abolish slavery of whatever name and form and all its badges and incidents; to render impossible any state of bondage; to make labor free, by prohibiting that control by which the personal service of one man is disposed of or coerced for another's benefit, which is the essence of involuntary servitude. While the Amendment was self-executing, so far as its terms were applicable to any existing condition, Congress was authorized to secure its complete enforcement by appropriate legislation.

Jones and beyond

Legal histories cite Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co. (1968) as a turning point of Thirteen Amendment jurisprudence. The Supreme Court confirmed in Jones that Congress may act "rationally" to prevent private actors from imposing "badges and incidents of servitude". The Joneses were a black couple in St. Louis County, Missouri who sued a real estate company for refusing to sell them a house. The Court held:Congress has the power under the Thirteenth Amendment rationally to determine what are the badges and the incidents of slavery, and the authority to translate that determination into effective legislation. ... this Court recognized long ago that, whatever else they may have encompassed, the badges and incidents of slavery – its "burdens and disabilities" – included restraints upon "those fundamental rights which are the essence of civil freedom, namely, the same right ... to inherit, purchase, lease, sell and convey property, as is enjoyed by white citizens." Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3, 109 U. S. 22.

Just as the Black Codes, enacted after the Civil War to restrict the free exercise of those rights, were substitutes for the slave system, so the exclusion of Negroes from white communities became a substitute for the Black Codes. And when racial discrimination herds men into ghettos and makes their ability to buy property turn on the color of their skin, then it too is a relic of slavery.

Negro citizens, North and South, who saw in the Thirteenth Amendment a promise of freedom—freedom to "go and come at pleasure" and to "buy and sell when they please"—would be left with "a mere paper guarantee" if Congress were powerless to assure that a dollar in the hands of a Negro will purchase the same thing as a dollar in the hands of a white man. At the very least, the freedom that Congress is empowered to secure under the Thirteenth Amendment includes the freedom to buy whatever a white man can buy, the right to live wherever a white man can live. If Congress cannot say that being a free man means at least this much, then the Thirteenth Amendment made a promise the Nation cannot keep.The Court in Jones reopened the issue of linking racism in contemporary society to the history of slavery in the United States.

The Jones precedent has been used to justify Congressional action to protect migrant workers and target sex trafficking. The direct enforcement power found in the Thirteenth Amendment contrasts with that of the Fourteenth, which allows only responses to institutional discrimination of state actors.

Other cases of involuntary servitude

The Supreme Court has taken an especially narrow view of involuntary servitude claims made by people not descended from black (African) slaves. In Robertson v. Baldwin (1897), a group of merchant seamen challenged federal statutes which criminalized a seaman's failure to complete their contractual term of service. The Court ruled that seamen's contracts had been considered unique from time immemorial, and that "the amendment was not intended to introduce any novel doctrine with respect to certain descriptions of service which have always been treated as exceptional". In this case, as in numerous "badges and incidents" cases, Justice Harlan authored a dissent favoring broader Thirteenth Amendment protections.In Selective Draft Law Cases, the Supreme Court ruled that the military draft was not "involuntary servitude". In United States v. Kozminski, the Supreme Court ruled that the Thirteenth Amendment did not prohibit compulsion of servitude through psychological coercion. Kozminski defined involuntary servitude for purposes of criminal prosecution as "a condition of servitude in which the victim is forced to work for the defendant by the use or threat of physical restraint or physical injury or by the use or threat of coercion through law or the legal process. This definition encompasses cases in which the defendant holds the victim in servitude by placing him or her in fear of such physical restraint or injury or legal coercion."

The U.S. Courts of Appeals, in Immediato v. Rye Neck School District, Herndon v. Chapel Hill, and Steirer v. Bethlehem School District, have ruled that the use of community service as a high school graduation requirement did not violate the Thirteenth Amendment.

Prior proposed Thirteenth Amendments

During the six decades following the 1804 ratification of the Twelfth Amendment two proposals to amend the Constitution were adopted by Congress and sent to the states for ratification. Neither has been ratified by the number of states necessary to become part of the Constitution. Commonly known as the Titles of Nobility Amendment and the Corwin Amendment, both are referred to as Article Thirteen, as was the successful Thirteenth Amendment, in the joint resolution passed by Congress.- The Titles of Nobility Amendment (pending before the states since May 1, 1810) would, if ratified, strip citizenship from any United States citizen who accepts a title of nobility or honor from a foreign country without the consent of Congress.

- The Corwin Amendment (pending before the states since March 2, 1861) would, if ratified, shield "domestic institutions" of the states (in 1861 this was a common euphemism for slavery) from the constitutional amendment process and from abolition or interference by Congress.