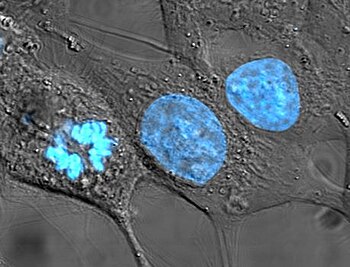

HeLa cells stained for nuclear DNA with the blue fluorescent Hoechst dye. The central and rightmost cell are in interphase, thus their entire nuclei are labeled. On the left, a cell is going through mitosis and its DNA has condensed.

| Cell biology | |

|---|---|

| The animal cell | |

Components of a typical animal cell:

|

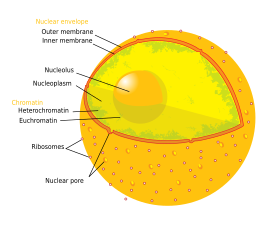

Cell nuclei contain most of the cell's genetic material, organized as multiple long linear DNA molecules in a complex with a large variety of proteins, such as histones, to form chromosomes. The genes within these chromosomes are the cell's nuclear genome and are structured in such a way to promote cell function. The nucleus maintains the integrity of genes and controls the activities of the cell by regulating gene expression—the nucleus is, therefore, the control center of the cell. The main structures making up the nucleus are the nuclear envelope, a double membrane that encloses the entire organelle and isolates its contents from the cellular cytoplasm, and the nuclear matrix (which includes the nuclear lamina), a network within the nucleus that adds mechanical support, much like the cytoskeleton, which supports the cell as a whole.

Because the nuclear envelope is impermeable to large molecules, nuclear pores are required to regulate nuclear transport of molecules across the envelope. The pores cross both nuclear membranes, providing a channel through which larger molecules must be actively transported by carrier proteins while allowing free movement of small molecules and ions. Movement of large molecules such as proteins and RNA through the pores is required for both gene expression and the maintenance of chromosomes. Although the interior of the nucleus does not contain any membrane-bound subcompartments, its contents are not uniform, and a number of sub-nuclear bodies exist, made up of unique proteins, RNA molecules, and particular parts of the chromosomes. The best-known of these is the nucleolus, which is mainly involved in the assembly of ribosomes. After being produced in the nucleolus, ribosomes are exported to the cytoplasm where they translate mRNA.

History

Oldest known depiction of cells and their nuclei by Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, 1719

Drawing of a Chironomus salivary gland cell published by Walther Flemming in 1882. The nucleus contains Polytene chromosomes.

The nucleus was the first organelle to be discovered. What is most likely the oldest preserved drawing dates back to the early microscopist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (1632–1723). He observed a "lumen", the nucleus, in the red blood cells of salmon. Unlike mammalian red blood cells, those of other vertebrates still contain nuclei.

The nucleus was also described by Franz Bauer in 1804 and in more detail in 1831 by Scottish botanist Robert Brown in a talk at the Linnean Society of London. Brown was studying orchids under microscope when he observed an opaque area, which he called the "areola" or "nucleus", in the cells of the flower's outer layer.

He did not suggest a potential function. In 1838, Matthias Schleiden proposed that the nucleus plays a role in generating cells, thus he introduced the name "cytoblast" (cell builder). He believed that he had observed new cells assembling around "cytoblasts". Franz Meyen was a strong opponent of this view, having already described cells multiplying by division and believing that many cells would have no nuclei. The idea that cells can be generated de novo, by the "cytoblast" or otherwise, contradicted work by Robert Remak (1852) and Rudolf Virchow (1855) who decisively propagated the new paradigm that cells are generated solely by cells ("Omnis cellula e cellula"). The function of the nucleus remained unclear.

Between 1877 and 1878, Oscar Hertwig published several studies on the fertilization of sea urchin eggs, showing that the nucleus of the sperm enters the oocyte and fuses with its nucleus. This was the first time it was suggested that an individual develops from a (single) nucleated cell. This was in contradiction to Ernst Haeckel's theory that the complete phylogeny of a species would be repeated during embryonic development, including generation of the first nucleated cell from a "monerula", a structureless mass of primordial mucus ("Urschleim"). Therefore, the necessity of the sperm nucleus for fertilization was discussed for quite some time. However, Hertwig confirmed his observation in other animal groups, including amphibians and molluscs. Eduard Strasburger produced the same results for plants in 1884. This paved the way to assign the nucleus an important role in heredity. In 1873, August Weismann postulated the equivalence of the maternal and paternal germ cells for heredity. The function of the nucleus as carrier of genetic information became clear only later, after mitosis was discovered and the Mendelian rules were rediscovered at the beginning of the 20th century; the chromosome theory of heredity was therefore developed.

Structures

The nucleus is the largest cellular organelle in animal cells. In mammalian cells, the average diameter of the nucleus is approximately 6 micrometres (µm), which occupies about 10% of the total cell volume. The viscous liquid within it is called nucleoplasm (or karyolymph), and is similar in composition to the cytosol found outside the nucleus. It appears as a dense, roughly spherical or irregular organelle. The composition by dry weight of the nucleus is approximately: DNA 9%, RNA 1%, Histone Protein 11%, Residual Protein 14%, Acidic Proteins 65%.In some types of white blood cells specifically most granulocytes the nucleus is lobated and can be present as a bi-lobed, tri-lobed or multi-lobed organelle.

Nuclear envelope and pores

The eukaryotic cell nucleus. Visible in this diagram

are the ribosome-studded double membranes of the

nuclear envelope, the DNA (complexed as chromatin),

and the nucleolus. Within the cell nucleus is a viscous

liquid called nucleoplasm, similar to the cytoplasm

found outside the nucleus.

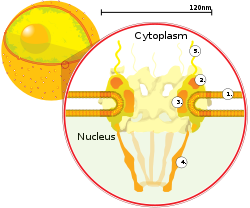

A cross section of a nuclear pore on the

surface of the nuclear envelope (1). Other

diagram labels show (2) the outer ring, (3)

spokes, (4) basket, and (5) filaments.

The nuclear envelope, otherwise known as nuclear membrane, consists of two cellular membranes, an inner and an outer membrane, arranged parallel to one another and separated by 10 to 50 nanometres (nm). The nuclear envelope completely encloses the nucleus and separates the cell's genetic material from the surrounding cytoplasm, serving as a barrier to prevent macromolecules from diffusing freely between the nucleoplasm and the cytoplasm. The outer nuclear membrane is continuous with the membrane of the rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER), and is similarly studded with ribosomes. The space between the membranes is called the perinuclear space and is continuous with the RER lumen.

Nuclear pores, which provide aqueous channels through the envelope, are composed of multiple proteins, collectively referred to as nucleoporins. The pores are about 125 million daltons in molecular weight and consist of around 50 (in yeast) to several hundred proteins (in vertebrates). The pores are 100 nm in total diameter; however, the gap through which molecules freely diffuse is only about 9 nm wide, due to the presence of regulatory systems within the center of the pore. This size selectively allows the passage of small water-soluble molecules while preventing larger molecules, such as nucleic acids and larger proteins, from inappropriately entering or exiting the nucleus. These large molecules must be actively transported into the nucleus instead. The nucleus of a typical mammalian cell will have about 3000 to 4000 pores throughout its envelope, each of which contains an eightfold-symmetric ring-shaped structure at a position where the inner and outer membranes fuse. Attached to the ring is a structure called the nuclear basket that extends into the nucleoplasm, and a series of filamentous extensions that reach into the cytoplasm. Both structures serve to mediate binding to nuclear transport proteins.

Most proteins, ribosomal subunits, and some DNAs are transported through the pore complexes in a process mediated by a family of transport factors known as karyopherins. Those karyopherins that mediate movement into the nucleus are also called importins, whereas those that mediate movement out of the nucleus are called exportins. Most karyopherins interact directly with their cargo, although some use adaptor proteins. Steroid hormones such as cortisol and aldosterone, as well as other small lipid-soluble molecules involved in intercellular signaling, can diffuse through the cell membrane and into the cytoplasm, where they bind nuclear receptor proteins that are trafficked into the nucleus. There they serve as transcription factors when bound to their ligand; in the absence of a ligand, many such receptors function as histone deacetylases that repress gene expression.

Nuclear lamina

In animal cells, two networks of intermediate filaments provide the nucleus with mechanical support: The nuclear lamina forms an organized meshwork on the internal face of the envelope, while less organized support is provided on the cytosolic face of the envelope. Both systems provide structural support for the nuclear envelope and anchoring sites for chromosomes and nuclear pores.The nuclear lamina is composed mostly of lamin proteins. Like all proteins, lamins are synthesized in the cytoplasm and later transported to the nucleus interior, where they are assembled before being incorporated into the existing network of nuclear lamina. Lamins found on the cytosolic face of the membrane, such as emerin and nesprin, bind to the cytoskeleton to provide structural support. Lamins are also found inside the nucleoplasm where they form another regular structure, known as the nucleoplasmic veil, that is visible using fluorescence microscopy. The actual function of the veil is not clear, although it is excluded from the nucleolus and is present during interphase. Lamin structures that make up the veil, such as LEM3, bind chromatin and disrupting their structure inhibits transcription of protein-coding genes.

Like the components of other intermediate filaments, the lamin monomer contains an alpha-helical domain used by two monomers to coil around each other, forming a dimer structure called a coiled coil. Two of these dimer structures then join side by side, in an antiparallel arrangement, to form a tetramer called a protofilament. Eight of these protofilaments form a lateral arrangement that is twisted to form a ropelike filament. These filaments can be assembled or disassembled in a dynamic manner, meaning that changes in the length of the filament depend on the competing rates of filament addition and removal.

Mutations in lamin genes leading to defects in filament assembly cause a group of rare genetic disorders known as laminopathies. The most notable laminopathy is the family of diseases known as progeria, which causes the appearance of premature aging in its sufferers. The exact mechanism by which the associated biochemical changes give rise to the aged phenotype is not well understood.

Chromosomes

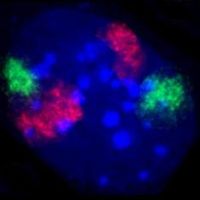

A mouse fibroblast nucleus in which DNA is stained blue. The distinct chromosome territories of chromosome 2 (red) and chromosome 9 (green) are stained with fluorescent in situ hybridization.

The cell nucleus contains the majority of the cell's genetic material in the form of multiple linear DNA molecules organized into structures called chromosomes. Each human cell contains roughly two meters of DNA. During most of the cell cycle these are organized in a DNA-protein complex known as chromatin, and during cell division the chromatin can be seen to form the well-defined chromosomes familiar from a karyotype. A small fraction of the cell's genes are located instead in the mitochondria.

There are two types of chromatin. Euchromatin is the less compact DNA form, and contains genes that are frequently expressed by the cell. The other type, heterochromatin, is the more compact form, and contains DNA that is infrequently transcribed. This structure is further categorized into facultative heterochromatin, consisting of genes that are organized as heterochromatin only in certain cell types or at certain stages of development, and constitutive heterochromatin that consists of chromosome structural components such as telomeres and centromeres. During interphase the chromatin organizes itself into discrete individual patches, called chromosome territories. Active genes, which are generally found in the euchromatic region of the chromosome, tend to be located towards the chromosome's territory boundary.

Antibodies to certain types of chromatin organization, in particular, nucleosomes, have been associated with a number of autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus. These are known as anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA) and have also been observed in concert with multiple sclerosis as part of general immune system dysfunction. As in the case of progeria, the role played by the antibodies in inducing the symptoms of autoimmune diseases is not obvious.

Nucleolus

An electron micrograph of a cell nucleus, showing the darkly stained nucleolus

3D rendering of nucleus with location of nucleolus

The nucleolus is a discrete densely stained structure found in the nucleus. It is not surrounded by a membrane, and is sometimes called a suborganelle. It forms around tandem repeats of rDNA, DNA coding for ribosomal RNA (rRNA). These regions are called nucleolar organizer regions (NOR). The main roles of the nucleolus are to synthesize rRNA and assemble ribosomes. The structural cohesion of the nucleolus depends on its activity, as ribosomal assembly in the nucleolus results in the transient association of nucleolar components, facilitating further ribosomal assembly, and hence further association. This model is supported by observations that inactivation of rDNA results in intermingling of nucleolar structures.

In the first step of ribosome assembly, a protein called RNA polymerase I transcribes rDNA, which forms a large pre-rRNA precursor. This is cleaved into the subunits 5.8S, 18S, and 28S rRNA. The transcription, post-transcriptional processing, and assembly of rRNA occurs in the nucleolus, aided by small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA) molecules, some of which are derived from spliced introns from messenger RNAs encoding genes related to ribosomal function. The assembled ribosomal subunits are the largest structures passed through the nuclear pores.

When observed under the electron microscope, the nucleolus can be seen to consist of three distinguishable regions: the innermost fibrillar centers (FCs), surrounded by the dense fibrillar component (DFC), which in turn is bordered by the granular component (GC). Transcription of the rDNA occurs either in the FC or at the FC-DFC boundary, and, therefore, when rDNA transcription in the cell is increased, more FCs are detected. Most of the cleavage and modification of rRNAs occurs in the DFC, while the latter steps involving protein assembly onto the ribosomal subunits occur in the GC.

Other subnuclear bodies

| Structure name | Structure diameter | |

|---|---|---|

| Cajal bodies | 0.2–2.0 µm |

|

| Clastosomes | 0.2-0.5 µm |

|

| PIKA | 5 µm |

|

| PML bodies | 0.2–1.0 µm |

|

| Paraspeckles | 0.5–1.0 µm |

|

| Speckles | 20–25 nm |

|

Other subnuclear structures appear as part of abnormal disease processes. For example, the presence of small intranuclear rods has been reported in some cases of nemaline myopathy. This condition typically results from mutations in actin, and the rods themselves consist of mutant actin as well as other cytoskeletal proteins.

Cajal bodies and gems

A nucleus typically contains between 1 and 10 compact structures called Cajal bodies or coiled bodies (CB), whose diameter measures between 0.2 µm and 2.0 µm depending on the cell type and species. When seen under an electron microscope, they resemble balls of tangled thread and are dense foci of distribution for the protein coilin. CBs are involved in a number of different roles relating to RNA processing, specifically small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA) and small nuclear RNA (snRNA) maturation, and histone mRNA modification.Similar to Cajal bodies are Gemini of Cajal bodies, or gems, whose name is derived from the Gemini constellation in reference to their close "twin" relationship with CBs. Gems are similar in size and shape to CBs, and in fact are virtually indistinguishable under the microscope. Unlike CBs, gems do not contain small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs), but do contain a protein called survival of motor neuron (SMN) whose function relates to snRNP biogenesis. Gems are believed to assist CBs in snRNP biogenesis, though it has also been suggested from microscopy evidence that CBs and gems are different manifestations of the same structure. Later ultrastructural studies have shown gems to be twins of Cajal bodies with the difference being in the coilin component; Cajal bodies are SMN positive and coilin positive, and gems are SMN positive and coilin negative.

RAFA and PTF domains

RAFA domains, or polymorphic interphase karyosomal associations, were first described in microscopy studies in 1991. Their function remains unclear, though they were not thought to be associated with active DNA replication, transcription, or RNA processing. They have been found to often associate with discrete domains defined by dense localization of the transcription factor PTF, which promotes transcription of small nuclear RNA (snRNA).PML bodies

Promyelocytic leukaemia bodies (PML bodies) are spherical bodies found scattered throughout the nucleoplasm, measuring around 0.1–1.0 µm. They are known by a number of other names, including nuclear domain 10 (ND10), Kremer bodies, and PML oncogenic domains. PML bodies are named after one of their major components, the promyelocytic leukemia protein (PML). They are often seen in the nucleus in association with Cajal bodies and cleavage bodies. PML bodies belong to the nuclear matrix, an ill-defined super-structure of the nucleus proposed to anchor and regulate many nuclear functions, including DNA replication, transcription, or epigenetic silencing. The PML protein is the key organizer of these domains that recruits an ever-growing number of proteins, whose only common known feature to date is their ability to be SUMOylated. Yet, pml-/- mice (which have their PML gene deleted) cannot assemble nuclear bodies, develop normally and live well, demonstrating that PML bodies are dispensable for most basic biological functions.Splicing speckles

Speckles are subnuclear structures that are enriched in pre-messenger RNA splicing factors and are located in the interchromatin regions of the nucleoplasm of mammalian cells. At the fluorescence-microscope level they appear as irregular, punctate structures, which vary in size and shape, and when examined by electron microscopy they are seen as clusters of interchromatin granules. Speckles are dynamic structures, and both their protein and RNA-protein components can cycle continuously between speckles and other nuclear locations, including active transcription sites. Studies on the composition, structure and behaviour of speckles have provided a model for understanding the functional compartmentalization of the nucleus and the organization of the gene-expression machinery splicing snRNPs and other splicing proteins necessary for pre-mRNA processing. Because of a cell's changing requirements, the composition and location of these bodies changes according to mRNA transcription and regulation via phosphorylation of specific proteins. The splicing speckles are also known as nuclear speckles (nuclear specks), splicing factor compartments (SF compartments), interchromatin granule clusters (IGCs), B snurposomes. B snurposomes are found in the amphibian oocyte nuclei and in Drosophila melanogaster embryos. B snurposomes appear alone or attached to the Cajal bodies in the electron micrographs of the amphibian nuclei. IGCs function as storage sites for the splicing factors.Paraspeckles

Discovered by Fox et al. in 2002, paraspeckles are irregularly shaped compartments in the interchromatin space of the nucleus. First documented in HeLa cells, where there are generally 10–30 per nucleus, paraspeckles are now known to also exist in all human primary cells, transformed cell lines, and tissue sections. Their name is derived from their distribution in the nucleus; the "para" is short for parallel and the "speckles" refers to the splicing speckles to which they are always in close proximity.Paraspeckles are dynamic structures that are altered in response to changes in cellular metabolic activity. They are transcription dependent and in the absence of RNA Pol II transcription, the paraspeckle disappears and all of its associated protein components (PSP1, p54nrb, PSP2, CFI(m)68, and PSF) form a crescent shaped perinucleolar cap in the nucleolus. This phenomenon is demonstrated during the cell cycle. In the cell cycle, paraspeckles are present during interphase and during all of mitosis except for telophase. During telophase, when the two daughter nuclei are formed, there is no RNA Pol II transcription so the protein components instead form a perinucleolar cap.

Perichromatin fibrils

Perichromatin fibrils are visible only under electron microscope. They are located next to the transcriptionally active chromatin and are hypothesized to be the sites of active pre-mRNA processing.Clastosomes

Clastosomes are small nuclear bodies (0.2–0.5 µm) described as having a thick ring-shape due to the peripheral capsule around these bodies. This name is derived from the Greek klastos, broken and soma, body. Clastosomes are not typically present in normal cells, making them hard to detect. They form under high proteolysis conditions within the nucleus and degrade once there is a decrease in activity or if cells are treated with proteasome inhibitors. The scarcity of clastosomes in cells indicates that they are not required for proteasome function. Osmotic stress has also been shown to cause the formation of clastosomes. These nuclear bodies contain catalytic and regulatory sub-units of the proteasome and its substrates, indicating that clastosomes are sites for degrading proteins.Function

The nucleus provides a site for genetic transcription that is segregated from the location of translation in the cytoplasm, allowing levels of gene regulation that are not available to prokaryotes. The main function of the cell nucleus is to control gene expression and mediate the replication of DNA during the cell cycle.The nucleus is an organelle found in eukaryotic cells. Inside its fully enclosed nuclear membrane, it contains the majority of the cell's genetic material. This material is organized as DNA molecules, along with a variety of proteins, to form chromosomes.

Cell compartmentalization

The nuclear envelope allows the nucleus to control its contents, and separate them from the rest of the cytoplasm where necessary. This is important for controlling processes on either side of the nuclear membrane. In most cases where a cytoplasmic process needs to be restricted, a key participant is removed to the nucleus, where it interacts with transcription factors to downregulate the production of certain enzymes in the pathway. This regulatory mechanism occurs in the case of glycolysis, a cellular pathway for breaking down glucose to produce energy. Hexokinase is an enzyme responsible for the first the step of glycolysis, forming glucose-6-phosphate from glucose. At high concentrations of fructose-6-phosphate, a molecule made later from glucose-6-phosphate, a regulator protein removes hexokinase to the nucleus, where it forms a transcriptional repressor complex with nuclear proteins to reduce the expression of genes involved in glycolysis.In order to control which genes are being transcribed, the cell separates some transcription factor proteins responsible for regulating gene expression from physical access to the DNA until they are activated by other signaling pathways. This prevents even low levels of inappropriate gene expression. For example, in the case of NF-κB-controlled genes, which are involved in most inflammatory responses, transcription is induced in response to a signal pathway such as that initiated by the signaling molecule TNF-α, binds to a cell membrane receptor, resulting in the recruitment of signalling proteins, and eventually activating the transcription factor NF-κB. A nuclear localisation signal on the NF-κB protein allows it to be transported through the nuclear pore and into the nucleus, where it stimulates the transcription of the target genes.

The compartmentalization allows the cell to prevent translation of unspliced mRNA. Eukaryotic mRNA contains introns that must be removed before being translated to produce functional proteins. The splicing is done inside the nucleus before the mRNA can be accessed by ribosomes for translation. Without the nucleus, ribosomes would translate newly transcribed (unprocessed) mRNA, resulting in malformed and nonfunctional proteins.

Gene expression

A micrograph of ongoing gene transcription of ribosomal RNA illustrating the growing primary transcripts. "Begin" indicates the 5' end of the DNA, where new RNA synthesis begins; "end" indicates the 3' end, where the primary transcripts are almost complete.

Gene expression first involves transcription, in which DNA is used as a template to produce RNA. In the case of genes encoding proteins, that RNA produced from this process is messenger RNA (mRNA), which then needs to be translated by ribosomes to form a protein. As ribosomes are located outside the nucleus, mRNA produced needs to be exported.

Since the nucleus is the site of transcription, it also contains a variety of proteins that either directly mediate transcription or are involved in regulating the process. These proteins include helicases, which unwind the double-stranded DNA molecule to facilitate access to it, RNA polymerases, which bind to the DNA promoter to synthesize the growing RNA molecule, topoisomerases, which change the amount of supercoiling in DNA, helping it wind and unwind, as well as a large variety of transcription factors that regulate expression.

Processing of pre-mRNA

Newly synthesized mRNA molecules are known as primary transcripts or pre-mRNA. They must undergo post-transcriptional modification in the nucleus before being exported to the cytoplasm; mRNA that appears in the cytoplasm without these modifications is degraded rather than used for protein translation. The three main modifications are 5' capping, 3' polyadenylation, and RNA splicing. While in the nucleus, pre-mRNA is associated with a variety of proteins in complexes known as heterogeneous ribonucleoprotein particles (hnRNPs). Addition of the 5' cap occurs co-transcriptionally and is the first step in post-transcriptional modification. The 3' poly-adenine tail is only added after transcription is complete.RNA splicing, carried out by a complex called the spliceosome, is the process by which introns, or regions of DNA that do not code for protein, are removed from the pre-mRNA and the remaining exons connected to re-form a single continuous molecule. This process normally occurs after 5' capping and 3' polyadenylation but can begin before synthesis is complete in transcripts with many exons. Many pre-mRNAs, including those encoding antibodies, can be spliced in multiple ways to produce different mature mRNAs that encode different protein sequences. This process is known as alternative splicing, and allows production of a large variety of proteins from a limited amount of DNA.

Dynamics and regulation

Nuclear transport

Macromolecules, such as RNA and proteins, are actively transported across the nuclear membrane in a process called the Ran-GTP nuclear transport cycle.

The entry and exit of large molecules from the nucleus is tightly controlled by the nuclear pore complexes. Although small molecules can enter the nucleus without regulation, macromolecules such as RNA and proteins require association karyopherins called importins to enter the nucleus and exportins to exit. "Cargo" proteins that must be translocated from the cytoplasm to the nucleus contain short amino acid sequences known as nuclear localization signals, which are bound by importins, while those transported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm carry nuclear export signals bound by exportins. The ability of importins and exportins to transport their cargo is regulated by GTPases, enzymes that hydrolyze the molecule guanosine triphosphate (GTP) to release energy. The key GTPase in nuclear transport is Ran, which can bind either GTP or GDP (guanosine diphosphate), depending on whether it is located in the nucleus or the cytoplasm. Whereas importins depend on RanGTP to dissociate from their cargo, exportins require RanGTP in order to bind to their cargo.

Nuclear import depends on the importin binding its cargo in the cytoplasm and carrying it through the nuclear pore into the nucleus. Inside the nucleus, RanGTP acts to separate the cargo from the importin, allowing the importin to exit the nucleus and be reused. Nuclear export is similar, as the exportin binds the cargo inside the nucleus in a process facilitated by RanGTP, exits through the nuclear pore, and separates from its cargo in the cytoplasm.

Specialized export proteins exist for translocation of mature mRNA and tRNA to the cytoplasm after post-transcriptional modification is complete. This quality-control mechanism is important due to these molecules' central role in protein translation. Mis-expression of a protein due to incomplete excision of exons or mis-incorporation of amino acids could have negative consequences for the cell; thus, incompletely modified RNA that reaches the cytoplasm is degraded rather than used in translation.

Assembly and disassembly

An image of a newt lung cell stained with fluorescent dyes during metaphase. The mitotic spindle can be seen, stained green, attached to the two sets of chromosomes, stained light blue. All chromosomes but one are already at the metaphase plate.

During its lifetime, a nucleus may be broken down or destroyed, either in the process of cell division or as a consequence of apoptosis (the process of programmed cell death). During these events, the structural components of the nucleus — the envelope and lamina — can be systematically degraded. In most cells, the disassembly of the nuclear envelope marks the end of the prophase of mitosis. However, this disassembly of the nucleus is not a universal feature of mitosis and does not occur in all cells. Some unicellular eukaryotes (e.g., yeasts) undergo so-called closed mitosis, in which the nuclear envelope remains intact. In closed mitosis, the daughter chromosomes migrate to opposite poles of the nucleus, which then divides in two. The cells of higher eukaryotes, however, usually undergo open mitosis, which is characterized by breakdown of the nuclear envelope. The daughter chromosomes then migrate to opposite poles of the mitotic spindle, and new nuclei reassemble around them.

At a certain point during the cell cycle in open mitosis, the cell divides to form two cells. In order for this process to be possible, each of the new daughter cells must have a full set of genes, a process requiring replication of the chromosomes as well as segregation of the separate sets. This occurs by the replicated chromosomes, the sister chromatids, attaching to microtubules, which in turn are attached to different centrosomes. The sister chromatids can then be pulled to separate locations in the cell. In many cells, the centrosome is located in the cytoplasm, outside the nucleus; the microtubules would be unable to attach to the chromatids in the presence of the nuclear envelope. Therefore, the early stages in the cell cycle, beginning in prophase and until around prometaphase, the nuclear membrane is dismantled. Likewise, during the same period, the nuclear lamina is also disassembled, a process regulated by phosphorylation of the lamins by protein kinases such as the CDC2 protein kinase. Towards the end of the cell cycle, the nuclear membrane is reformed, and around the same time, the nuclear lamina are reassembled by dephosphorylating the lamins.

However, in dinoflagellates, the nuclear envelope remains intact, the centrosomes are located in the cytoplasm, and the microtubules come in contact with chromosomes, whose centromeric regions are incorporated into the nuclear envelope (the so-called closed mitosis with extranuclear spindle). In many other protists (e.g., ciliates, sporozoans) and fungi, the centrosomes are intranuclear, and their nuclear envelope also does not disassemble during cell division.

Apoptosis is a controlled process in which the cell's structural components are destroyed, resulting in death of the cell. Changes associated with apoptosis directly affect the nucleus and its contents, for example, in the condensation of chromatin and the disintegration of the nuclear envelope and lamina. The destruction of the lamin networks is controlled by specialized apoptotic proteases called caspases, which cleave the lamin proteins and, thus, degrade the nucleus' structural integrity. Lamin cleavage is sometimes used as a laboratory indicator of caspase activity in assays for early apoptotic activity. Cells that express mutant caspase-resistant lamins are deficient in nuclear changes related to apoptosis, suggesting that lamins play a role in initiating the events that lead to apoptotic degradation of the nucleus. Inhibition of lamin assembly itself is an inducer of apoptosis.

The nuclear envelope acts as a barrier that prevents both DNA and RNA viruses from entering the nucleus. Some viruses require access to proteins inside the nucleus in order to replicate and/or assemble. DNA viruses, such as herpesvirus replicate and assemble in the cell nucleus, and exit by budding through the inner nuclear membrane. This process is accompanied by disassembly of the lamina on the nuclear face of the inner membrane.

Initially, it has been suspected that immunoglobulins in general and autoantibodies in particular do not enter the nucleus. Now there is a body of evidence that under pathological conditions (e.g. lupus erythematosus) IgG can enter the nucleus.

Nuclei per cell

Most eukaryotic cell types usually have a single nucleus, but some have no nuclei, while others have several. This can result from normal development, as in the maturation of mammalian red blood cells, or from faulty cell division.Anucleated cells

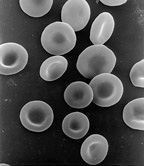

Human red blood cells, like those of other mammals, lack nuclei. This occurs as a normal part of the cells' development.

An anucleated cell contains no nucleus and is, therefore, incapable of dividing to produce daughter cells. The best-known anucleated cell is the mammalian red blood cell, or erythrocyte, which also lacks other organelles such as mitochondria, and serves primarily as a transport vessel to ferry oxygen from the lungs to the body's tissues. Erythrocytes mature through erythropoiesis in the bone marrow, where they lose their nuclei, organelles, and ribosomes. The nucleus is expelled during the process of differentiation from an erythroblast to a reticulocyte, which is the immediate precursor of the mature erythrocyte. The presence of mutagens may induce the release of some immature "micronucleated" erythrocytes into the bloodstream. Anucleated cells can also arise from flawed cell division in which one daughter lacks a nucleus and the other has two nuclei.

In flowering plants, this condition occurs in sieve tube elements.

Multinucleated cells

Multinucleated cells contain multiple nuclei. Most acantharean species of protozoa and some fungi in mycorrhizae have naturally multinucleated cells. Other examples include the intestinal parasites in the genus Giardia, which have two nuclei per cell. In humans, skeletal muscle cells, called myocytes and syncytium, become multinucleated during development; the resulting arrangement of nuclei near the periphery of the cells allows maximal intracellular space for myofibrils. Other multinucleate cells in the human are osteoclasts a type of bone cell. Multinucleated and binucleated cells can also be abnormal in humans; for example, cells arising from the fusion of monocytes and macrophages, known as giant multinucleated cells, sometimes accompany inflammation and are also implicated in tumor formation.A number of dinoflagellates are known to have two nuclei. Unlike other multinucleated cells these nuclei contain two distinct lineages of DNA: one from the dinoflagellate and the other from a symbiotic diatom. The mitochondria and the plastids of the diatom somehow remain functional.

Evolution

As the major defining characteristic of the eukaryotic cell, the nucleus' evolutionary origin has been the subject of much speculation. Four major hypotheses have been proposed to explain the existence of the nucleus, although none have yet earned widespread support.The first model known as the "syntrophic model" proposes that a symbiotic relationship between the archaea and bacteria created the nucleus-containing eukaryotic cell. (Organisms of the Archaea and Bacteria domain have no cell nucleus.) It is hypothesized that the symbiosis originated when ancient archaea, similar to modern methanogenic archaea, invaded and lived within bacteria similar to modern myxobacteria, eventually forming the early nucleus. This theory is analogous to the accepted theory for the origin of eukaryotic mitochondria and chloroplasts, which are thought to have developed from a similar endosymbiotic relationship between proto-eukaryotes and aerobic bacteria. The archaeal origin of the nucleus is supported by observations that archaea and eukarya have similar genes for certain proteins, including histones. Observations that myxobacteria are motile, can form multicellular complexes, and possess kinases and G proteins similar to eukarya, support a bacterial origin for the eukaryotic cell.

A second model proposes that proto-eukaryotic cells evolved from bacteria without an endosymbiotic stage. This model is based on the existence of modern planctomycetes bacteria that possess a nuclear structure with primitive pores and other compartmentalized membrane structures. A similar proposal states that a eukaryote-like cell, the chronocyte, evolved first and phagocytosed archaea and bacteria to generate the nucleus and the eukaryotic cell.

The most controversial model, known as viral eukaryogenesis, posits that the membrane-bound nucleus, along with other eukaryotic features, originated from the infection of a prokaryote by a virus. The suggestion is based on similarities between eukaryotes and viruses such as linear DNA strands, mRNA capping, and tight binding to proteins (analogizing histones to viral envelopes). One version of the proposal suggests that the nucleus evolved in concert with phagocytosis to form an early cellular "predator". Another variant proposes that eukaryotes originated from early archaea infected by poxviruses, on the basis of observed similarity between the DNA polymerases in modern poxviruses and eukaryotes. It has been suggested that the unresolved question of the evolution of sex could be related to the viral eukaryogenesis hypothesis.

A more recent proposal, the exomembrane hypothesis, suggests that the nucleus instead originated from a single ancestral cell that evolved a second exterior cell membrane; the interior membrane enclosing the original cell then became the nuclear membrane and evolved increasingly elaborate pore structures for passage of internally synthesized cellular components such as ribosomal subunits.