From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Hinduism and

Buddhism have common origins in the

Ganges culture of northern India during the so-called

"second urbanisation" around 500 BC. They have shared parallel beliefs that have existed side by side, but also pronounced differences.

Buddhism attained prominence in the Indian subcontinent as it was supported by royal courts, but started to decline after the

Gupta era, and

virtually disappeared from India

in the 11th century CE, except in some pockets of India. It has

continued to exist outside India and is the major religion in several

Asian countries.

Upanishads

Certain Buddhist teachings appear to have been formulated in response to ideas presented in the early

Upanishads – in some cases concurring with them, and in other cases criticizing or re-interpreting them.

The influence of Upanishads, the earliest philosophical texts of

Hindus, on Buddhism has been a subject of debate among scholars. While

Radhakrishnan,

Oldenberg and

Neumann were convinced of Upanishadic influence on the Buddhist canon,

Eliot and

Thomas highlighted the points where Buddhism was opposed to Upanishads.

Buddhism may have been influenced by some Upanishadic ideas, it however discarded their orthodox tendencies. In Buddhist texts he is presented as rejecting avenues of salvation as "pernicious views". Later schools of Indian religious thought were influenced by this

interpretation and novel ideas of the Buddhist tradition of beliefs.

Royal support

In

later years, there is significant evidence that both Buddhism and

Hinduism were supported by Indian rulers, regardless of the rulers' own

religious identities. Buddhist kings continued to revere Hindu deities

and teachers, and many Buddhist temples were built under the patronage

of Hindu rulers.

This was because never has Buddhism been considered an alien religion

to that of Hinduism in India, but as only one of the many strains of

Hinduism.

Kalidas' work shows the ascension of Hinduism at the expense of Buddhism. By the eighth century,

Shiva and

Vishnu had replaced

Buddha in

pujas of royalty.

Similarities

Basic vocabulary

The

Buddha approved many of the terms already used in philosophical

discussions of his era; however, many of these terms carry a different

meaning in the Buddhist tradition. For example, in the

Samaññaphala Sutta, the Buddha is depicted presenting a notion of the "three knowledges" (

tevijja) – a term also used in the Vedic tradition to describe knowledge of the

Vedas – as being not texts, but things that he had experienced (these are not noble truths).

The true "three knowledges" are said to be constituted by the process

of achieving enlightenment, which is what the Buddha is said to have

achieved in the three watches of the night of his enlightenment.

Karma

Karma (

Sanskrit: कर्म from the root kṛ, "to do") is a word meaning

action or

activity and often implies its subsequent

results (also called karma-phala, "the fruits of action"). It is commonly understood as a term to denote the entire cycle of

cause and effect as described in the philosophies of a number of cosmologies, including those of Buddhism and Hinduism.

Karma is a central part of Buddhist teachings. In Buddha's teaching, karma is a direct intentional

result of a person's word, thought and/or action in life. In

pre-Buddhist Vedic culture, karma has to do with whether or not the

ritualistic actions are correctly performed. Little emphasis is placed

on moral conduct in the early Vedic conception. In Buddhism, by contrast, a person's words, thoughts and/or actions form the basis for good and bad karma:

sila

(moral conduct) goes hand in hand with the development of meditation

and wisdom. Buddhist teachings carry a markedly different meaning from

pre-Buddhist conceptions of karma.

Dharma

Dharma (

Sanskrit,

Devanagari: धर्म or

Pāli Dhamma, Devanagari: धम्म) means

Natural Law,

Reality or

Duty, and with respect to its significance for

spirituality and

religion might be considered

the Way of the Higher Truths. A Hindu appellation for

Hinduism itself is

Sanātana Dharma, which translates as "the eternal dharma." Similarly,

Buddhadharma is an appellation for

Buddhism. The general concept of dharma forms a basis for philosophies, beliefs and practices originating in

India. The four main ones are

Hinduism,

Buddhism,

Jainism (Jaina Dharma), and

Sikhism

(Sikha Dharma), all of whom retain the centrality of dharma in their

teachings. In these traditions, beings that live in harmony with dharma

proceed more quickly toward, according to the tradition,

Dharma Yukam,

Moksha, or

Nirvana (personal liberation). Dharma can refer generally to religious

duty, and also mean social order, right conduct, or simply virtue.

Buddha

The term "Buddha" too has appeared in Hindu scriptures before the birth of

Gautama Buddha. In the

Vayu Purana,

sage Daksha calls Lord Shiva as Buddha.

Similar symbolism

- Mudra: This is a symbolic hand-gesture expressing an emotion. Images of the Buddha almost always depict him performing some mudra.

- Dharma Chakra: The Dharma Chakra,

which appears on the national flag of India and the flag of the Thai

royal family, is a Buddhist symbol that is used by members of both

religions.

- Rudraksha: These are beads that devotees, usually monks, use for praying.

- Tilak: Many Hindu devotees mark their heads with a tilak, which is interpreted as a third eye. A similar mark is one of the characteristic physical characteristics of the Buddha.

- Swastika and Sauwastika:

both are sacred symbols. It can be either clockwise or

counter-clockwise and both are seen in Hinduism and Buddhism. The Buddha

is sometimes depicted with a sauwastika on his chest or the palms of

his hands.

Similar practices

Mantra

A

mantra (मन्त्र) is a

religious syllable or

poem, typically from the

Sanskrit language. Their use varies according to the school and philosophy associated with the mantra. They are primarily used as

spiritual conduits, words or vibrations that instill one-pointed

concentration

in the devotee. Other purposes have included religious ceremonies to

accumulate wealth, avoid danger, or eliminate enemies. Mantras existed

in the

historical Vedic religion,

Zoroastrianism and the Shramanic traditions, and thus they remain important in Buddhism and

Jainism as well as other faiths of Indian origin such as

Sikhism.

Yoga

The practice of

Yoga is intimately connected to the religious beliefs and practices of both Hinduism and Buddhism. However, there are distinct variations in the usage of yoga terminology in the two religions.

In Hinduism, the term "Yoga" commonly refers to the eight limbs of yoga as defined in the

Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, written some time after 100 BCE, and means "yoke", with the idea that one's individual

atman, or soul, would yoke or bind with the monistic entity that underlies everything (

brahman).

Yoga in Hinduism also known as being 'complex', based on yoking

(integrating). Yoga defines a specific process, it has an emphasis on

knowledge and practice, as well as being known to be 'mature' and

difficult.

The most basic meaning of this Sanskrit term is with technique. The

technique of the different forms of yoga is what makes the practice

meaningful. Yoga is not an easy or simple practice, viyoga is what is

described as simple. Yoga is difficult in the fact of displaying the

faith and meaning of Hinduism. Many Hindus tend to pick and choose

between the five forms of yoga because of the way they live their life

and how they want to practice it in the form they are most connected to.

In the

Vajrayana

Buddhism of Tibet, however, the term "Yoga" is simply used to refer to

any type of spiritual practice; from the various types of tantra (like

Kriyayoga or

Charyayoga) to '

Deity yoga' and '

guru yoga'. In the early translation phase of the

Sutrayana and

Tantrayana from India, China and other regions to Tibet, along with the practice lineages of

sadhana, codified in the

Nyingmapa canon, the most subtle 'conveyance' (Sanskrit:

yana) is

Adi Yoga (Sanskrit). A contemporary scholar with a focus on

Tibetan Buddhism,

Robert Thurman writes that Patanjali was influenced by the success of the

Buddhist monastic system to formulate his own matrix for the version of thought he considered orthodox.

Meditation

There

is a range of common terminology and common descriptions of the

meditative states that are seen as the foundation of meditation practice

in both Hindu Yoga and Buddhism. Many scholars have noted that the

concepts of

dhyana and

samādhi

- technical terms describing stages of meditative absorption – are

common to meditative practices in both Hinduism and Buddhism. Most

notable in this context is the relationship between the system of four

Buddhist

dhyana states (

Pali:

jhana) and the

samprajnata samadhi states of Classical Yoga. Also, many (Tibetan) Vajrayana practices of the

generation stage and

completion stage work with the

chakras, inner energy channels (

nadis) and

kundalini, called

tummo in Tibetan.

Differences

Despite

the similarities in terminology there exist differences between the two

religions. There is no evidence to show that Buddhism ever subscribed

to vedic sacrifices, vedic deities or caste.

The major differences are mentioned below.

God

Gautama Buddha was very ambiguous about the existence of a Creator Deity

Brahman and Eternal Self

Atman

and rejected them both. Various sources from the Pali Cannon and others

suggest that the Buddha taught that belief in a Creator deity was not

essential to attaining liberation from suffering, and perhaps chose to

ignore theological questions because they were "fascinating to discuss,"

and frequently brought about more conflict and anger than peace. The

Buddha did not deny the existence of the popular gods of the Vedic

pantheon, but rather argued that these

devas,

who may be in a more exalted state than humans, are still nevertheless

trapped in the same samsaric cycle of suffering as other beings and are

not necessarily worthy of veneration and worship. The focus of the

Noble Eightfold Path,

while inheriting many practices and ideologies from the previous Hindu

yogic tradition, deviates from the teachings of the Bhagavad Gita and

earlier works of the

Dharmic Religions in that liberation (

Nirvana or

Moksha)

is not attained via unity with Brahman (the Godhead), Self-realization

or worship. Rather, the Buddha's teaching centers around what

Eknath Easwaran

described as a "psychology of desire," that is attaining liberation

from suffering by extermination of self-will, selfish desire and

passions. This is not to say that such teachings are absent from the

previous Hindu tradition, rather they are singled out and separated from

Vedic Theology.

According to

Buddhologist Richard Hayes, the early Buddhist

Nikaya

literature treats the question of the existence of a creator god

"primarily from either an epistemological point of view or a moral point

of view". In these texts the

Buddha

is portrayed not as a creator-denying atheist who claims to be able to

prove such a God's nonexistence, but rather his focus is other teachers'

claims that their teachings lead to the highest good.

Citing the

Devadaha Sutta (Majjhima Nikaya 101), Hayes

states, "while the reader is left to conclude that it is attachment

rather than God, actions in past lives, fate, type of birth or efforts

in this life that is responsible for our experiences of sorrow, no

systematic argument is given in an attempt to disprove the existence of

God."

The Buddha (as portrayed in the Pali scriptures, the

agamas) set an important trend in

nontheism in Buddhism

by establishing a somewhat non-theistic view on the notion of an

omnipotent God, generally ignoring the issue as being irrelevant to his

teachings. Nevertheless, in many passages in the

Tripitaka gods (

devas

in Sanskrit) are mentioned and specific examples are given of

individuals who were reborn as a god, or gods who were reborn as humans.

Buddhist cosmology

recognizes various levels and types of gods, but none of these gods is

considered the creator of the world or of the human race.

- Buddha preaches that attachment with people was the cause of

sorrow when 'death' happens and therefore proposes detachment from

people. Hinduism though proposes detachment from fruits of action and stresses on performance of duty or dharma,

it is not solely focused on it. In Hinduism, Lord Shiva explains

'death' to be journey of the immortal soul in pursuit of 'Moksha' and

therefore a fact of life.

- While Buddhism says retirement into forest was open to everyone

regardless of caste, and although according to the vinaya (the code of

conduct for the Sangha) it is not possible to take ordination as a

Buddhist mendicant (a Bhikkhu or Bhikkhuni) under the age of 20 or

adulthood, this is still viewed as escapism by Hinduism. Pre-Buddhist,

non-brahman forest mendicants are criticised in the earliest group of

Upanishads. Hinduism allows for this to happen only after performing all

dharmas or duties of one's life, starting from studying

scriptures, working to support children and family and taking care of

aged parents and lastly after all the dharma done retire to the forest

and slowly meditate, fast and perform rituals and austerities (tapas),

until physical disintegration & to reach the ultimate truth or Brahman.

Buddhism by contrast emphasises realisation by the middle way (avoiding

extremes of luxury or austerities), seeing limited value in the rituals

and tapas and the danger of their mis-application.

- Buddhism explained that attachment is the cause of sorrow in

society. Therefore, Buddhism's cure for sorrow was detachment and

non-involvement (non-action or negative action). Hinduism on the other

hand explained that both sorrow or happiness is due to 'Karma' or past

actions and bad karma can be overcome and good karma can be obtained by

following dharma or righteous duty (pro-action or positive action) which

will ultimately provide 'Moksha' i.e. overcoming the cycle of life and

joining Brahman.

Buddhist canonical views about God and the priests are:

Well then, Vasettha, those

ancient sages versed in ancient scriptures, the authors of the verses,

the utterers of the verses, whose, ancient form of words so chanted,

uttered, or composed, the priests of today chant over again or repeat;

intoning or reciting exactly as has been intoned or recited-to wit,

Atthaka, Vamaka, Vamadeva, Vessamitta, Yamataggi, Angirasa, Bharadvaja,

Vasettha, Kassapa, and Bhagu – did even they speak thus, saying:

"We know it, we have seen it", where the creator is whence the creator

is?

Scholar-monk

Walpola Rahula

writes that man depends on God "for his own protection, safety, and

security, just as a child depends on his parent." He describes this as a

product of "ignorance, weakness, fear, and desire," and writes that

this "deeply and fanatically held belief" for man's consolation is

"false and empty" from the perspective of Buddhism. He writes that man

does not wish to hear or understand teachings against this belief, and

that the Buddha described his teachings as "against the current" for

this reason. He also wrote that for self-protection man created God and for self-preservation man created "soul".

In later Mahayana literature, however, the idea of an eternal,

all-pervading, all-knowing, immaculate, uncreated and deathless Ground

of Being (the dharmadhatu, inherently linked to the sattvadhatu, the

realm of beings), which is the Awakened Mind (bodhicitta) or Dharmakaya

("body of Truth") of the Buddha himself, is attributed to the Buddha in a

number of Mahayana sutras, and is found in various tantras as well. In

some Mahayana texts, such a principle is occasionally presented as

manifesting in a more personalised form as a primordial buddha, such as

Samantabhadra, Vajradhara, Vairochana, Amitabha and Adi-Buddha, among

others.

Rites and rituals

In later tradition such as Mahayana Buddhism in Japan, the

Shingon Fire Ritual (Homa /Yagna) and Urabon (Sanskrit: Ullambana) derives from Hindu traditions.

Similar rituals are common in Tibetan Buddhism. Both Mahayana Buddhism

and Hinduism share common rites, such as the purification rite of Homa

(Havan, Yagna in Sanskrit), prayers for the ancestors and deceased

(Ullambana in Sanskrit, Urabon in Japanese).

Caste

The Buddha repudiated the caste distinctions of the Brahmanical religion, by offering ordination to all regardless of caste.

While the caste system constitutes an assumed background to the

stories told in Buddhist scriptures, the sutras do not attempt to

justify or explain the system. In

Aggañña Sutta,

Buddha elaborates that if any of the caste does the following deeds:

killing, taking anything which is not given, take part in sexual

misconduct, lying, slandering, speaking rough words or nonsense, greedy,

cruel, and practice wrong beliefs; people would still see that they do

negative deeds and therefore are not worthy or deserving respect. They

will even get into trouble from their own deeds, whatever their caste

(Brahmin, Khattiya, Vessa, and Sudda) might be.

Cosmology and worldview

In

Buddhist cosmology, there are 31 planes of existence within samsara.

Beings in these realms are subject to rebirth after some period of

time, except for realms of the Non-Returners. Therefore, most of these

places are not the goal of the holy life in the Buddha's dispensation.

Buddhas are beyond all these 31 planes of existence after parinibbana.

Hindu texts mostly mentions the devas in Kamma Loka. Only the Hindu god

Brahma can be found in the Rupa loka. There are many realms above Brahma

realm that are accessible through meditation. Those in Brahma realm are

also subject to rebirth according to the Buddha.

Practices

To

have an idea of the differences between Buddhism and pre-existing

beliefs and practices during this time, we can look into the

Samaññaphala Sutta in the

Digha Nikaya of the

Pali Canon.

In this sutra, a king of Magadha listed the teachings from many

prominent and famous spiritual teachers around during that time. He also

asked the

Buddha

about his teaching when visiting him. The Buddha told the king about

the practices of his spiritual path. The list of various practices he

taught disciples as well as practices he doesn't encourage are listed.

The text, rather than stating what the new faith was, emphasized what

the new faith was not. Contemporaneous religious traditions were

caricatured and then negated. Though critical of prevailing religious

practices and social institutions on philosophical grounds, early

Buddhist texts exhibit a reactionary anxiety at having to compete in

religiously plural societies. Below are a few examples found in the

sutra:

Whereas some priests and

contemplatives... are addicted to high and luxurious furnishings such as

these — over-sized couches, couches adorned with carved animals,

long-haired coverlets, multi-colored patchwork coverlets, white woolen

coverlets, woolen coverlets embroidered with flowers or animal figures,

stuffed quilts, coverlets with fringe, silk coverlets embroidered with

gems; large woolen carpets; elephant, horse, and chariot rugs,

antelope-hide rugs, deer-hide rugs; couches with awnings, couches with

red cushions for the head and feet — he (a bhikkhu disciple of the

Buddha) abstains from using high and luxurious furnishings such as

these.

Whereas some priests and contemplatives... are addicted to

scents, cosmetics, and means of beautification such as these — rubbing

powders into the body, massaging with oils, bathing in perfumed water,

kneading the limbs, using mirrors, ointments, garlands, scents, ...

bracelets, head-bands, decorated walking sticks... fancy sunshades,

decorated sandals, turbans, gems, yak-tail whisks, long-fringed white

robes — he abstains from ... means of beautification such as these.

Whereas some priests and contemplatives... are addicted to

talking about lowly topics such as these — talking about kings, robbers,

ministers of state; armies, alarms, and battles; food and drink;

clothing, furniture, garlands, and scents; relatives; vehicles;

villages, towns, cities, the countryside; women and heroes; the gossip

of the street and the well; tales of the dead; tales of diversity

[philosophical discussions of the past and future], the creation of the

world and of the sea, and talk of whether things exist or not — he

abstains from talking about lowly topics such as

these...

Whereas some priests and contemplatives...are addicted to running

messages and errands for people such as these — kings, ministers of

state, noble warriors, priests, householders, or youths [who say], 'Go

here, go there, take this there, fetch that here' — he abstains from

running messages and errands for people such as these.

Whereas some priests and contemplatives...engage in scheming,

persuading, hinting, belittling, and pursuing gain with gain, he

abstains from forms of scheming and persuading [improper ways of trying

to gain material support from donors] such as these.

"Whereas some priests and contemplatives...maintain themselves by wrong

livelihood, by such lowly arts as: reading marks on the limbs [e.g.,

palmistry]; reading omens and signs; interpreting celestial events

[falling stars, comets]; interpreting dreams; reading marks on the body

[e.g., phrenology]; reading marks on cloth gnawed by mice; offering fire

oblations, oblations from a ladle, oblations of husks, rice powder,

rice grains, ghee, and oil; offering oblations from the mouth; offering

blood-sacrifices; making predictions based on the fingertips; geomancy;

laying demons in a cemetery; placing spells on spirits; reciting

house-protection charms; snake charming, poison-lore, scorpion-lore,

rat-lore, bird-lore, crow-lore; fortune-telling based on visions; giving

protective charms; interpreting the calls of birds and animals — he

abstains from wrong livelihood, from lowly arts such as these.

Whereas some priests and contemplatives...maintain themselves by

wrong livelihood, by such lowly arts as: determining lucky and unlucky

gems, garments, staffs, swords, spears, arrows, bows, and other weapons;

women, boys, girls, male slaves, female slaves; elephants, horses,

buffaloes, bulls, cows, goats, rams, fowl, quails, lizards, long-eared

rodents, tortoises, and other animals — he abstains from wrong

livelihood, from lowly arts such as these.

Whereas some priests and contemplatives... maintain themselves by

wrong livelihood, by such lowly arts as forecasting: the rulers will

march forth; the rulers will march forth and return; our rulers will

attack, and their rulers will retreat; their rulers will attack, and our

rulers will retreat; there will be triumph for our rulers and defeat

for their rulers; there will be triumph for their rulers and defeat for

our rulers; thus there will be triumph, thus there will be defeat — he

abstains from wrong livelihood, from lowly arts such as these.

Whereas some priests and contemplatives...maintain themselves by wrong

livelihood, by such lowly arts as forecasting: there will be a lunar

eclipse; there will be a solar eclipse; there will be an occultation of

an asterism; the sun and moon will go their normal courses; the sun and

moon will go astray; the asterisms will go their normal courses; the

asterisms will go astray; there will be a meteor shower; there will be a

darkening of the sky; there will be an earthquake; there will be

thunder coming from a clear sky; there will be a rising, a setting, a

darkening, a brightening of the sun, moon, and asterisms; such will be

the result of the lunar eclipse... the rising, setting, darkening,

brightening of the sun, moon, and asterisms — he abstains from wrong

livelihood, from lowly arts such as these.

Whereas some priests and contemplatives...maintain themselves by

wrong livelihood, by such lowly arts as forecasting: there will be

abundant rain; there will be a drought; there will be plenty; there will

be famine; there will be rest and security; there will be danger; there

will be disease; there will be freedom from disease; or they earn their

living by counting, accounting, calculation, composing poetry, or

teaching hedonistic arts and doctrines — he abstains from wrong

livelihood, from lowly arts such as these.

Whereas some priests and contemplatives...maintain themselves by

wrong livelihood, by such lowly arts as: calculating auspicious dates

for marriages, betrothals, divorces; for collecting debts or making

investments and loans; for being attractive or unattractive; curing

women who have undergone miscarriages or abortions; reciting spells to

bind a man's tongue, to paralyze his jaws, to make him lose control over

his hands, or to bring on deafness; getting oracular answers to

questions addressed to a mirror, to a young girl, or to a spirit medium;

worshipping the sun, worshipping the Great Brahma, bringing forth

flames from the mouth, invoking the goddess of luck — he abstains from

wrong livelihood, from lowly arts such as these.

Whereas some priests and contemplatives...maintain themselves by

wrong livelihood, by such lowly arts as: promising gifts to devas in

return for favors; fulfilling such promises; demonology; teaching

house-protection spells; inducing virility and impotence; consecrating

sites for construction; giving ceremonial mouthwashes and ceremonial

bathing; offering sacrificial fires; administering emetics, purges,

purges from above, purges from below, head-purges; administering

ear-oil, eye-drops, treatments through the nose, ointments, and

counter-ointments; practicing eye-surgery (or: extractive surgery),

general surgery, pediatrics; administering root-medicines binding

medicinal herbs — he abstains from wrong livelihood, from lowly arts

such as these.

Meditation

According to the Maha-Saccaka Sutta, the Buddha recalled a meditative

state he entered by chance as a child and abandoned the ascetic

practices he has been doing:

I thought, "I recall once, when my

father the Sakyan was working, and I was sitting in the cool shade of a

rose-apple tree, then — quite secluded from sensuality, secluded from

unskillful mental qualities — I entered & remained in the first

jhana: rapture & pleasure born from seclusion, accompanied by

directed thought & evaluation. Could that be the path to Awakening?"

Then following on that memory came the realization: "That is the path

to Awakening."

According to the Upakkilesa Sutta, after figuring out the cause of

the various obstacles and overcoming them, the Buddha was able to

penetrate the sign and enters 1st- 4th Jhana.

I also saw both the light and the

vision of forms. Shortly after the vision of light and shapes disappear.

I thought, "What is the cause and condition in which light and vision

of the forms disappear?”

Then consider the following: "The question arose in me and

because of doubt my concentration fell, when my concentration fell, the

light disappeared and the vision of forms. I act so that the question

does not arise in me again.”

I remained diligent, ardent, perceived both the light and the

vision of forms. Shortly after the vision of light and shapes disappear.

I thought, "What is the cause and condition in which light and vision

of the forms disappear?”

Then consider the following: “Inattention arose in me because of

inattention and my concentration has decreased, when my concentration

fell, the light disappeared and the vision of forms. I must act in such a

way that neither doubt nor disregard arise in me again.”

In the same way as above, the Buddha encountered many more obstacles

that caused the light to disappear and found his way out of them. These

include sloth and torpor, fear, elation, inertia, excessive energy,

energy deficient, desire, perception of diversity, and excessive

meditation on the ways. Finally, he was able to penetrate the light and

entered jhana.

The following descriptions in the Upakkilesa Sutta further show

how he find his way into the first four Jhanas, which he later

considered

samma samadhi.

When Anuruddha, I realized that

doubt is an imperfection of the mind, I dropped out of doubt, an

imperfection of the mind. When I realized that inattention ... sloth and

torpor ... fear ... elation ... inertia ... excessive energy ...

deficient energy ... desire ... perception of diversity ... excessive

meditation on the ways, I abandoned excessive meditation on the ways, an

imperfection of the mind.

When Anuruddha, I realized that doubt is an imperfection of the mind, I

dropped out of doubt, an imperfection of the mind. When I realized that

inattention ... sloth and torpor ... fear ... elation ... inertia ...

excessive energy ... deficient energy... desire ... perception of

diversity ... excessive meditation on the ways, I abandoned excessive

meditation on the ways, an imperfection of the mind, so I thought, ‘I

abandoned these imperfections of the mind. ‘ Now the concentration will

develop in three ways. ..And so, Anuruddha, develop concentration with

directed thought and sustained thought; developed concentration without

directed thought, but only with the sustained thought; developed

concentration without directed thought and without thought sustained,

developed with the concentration ecstasy; developed concentration

without ecstasy; develop concentration accompanied by happiness,

developing concentration accompanied by equanimity...When Anuruddha, I

developed concentration with directed thought and sustained thought to

the development ... when the concentration accompanied by fairness,

knowledge and vision arose in me: ‘My release is unshakable, this is my

last birth, now there are no more likely to be any condition.

According to the early scriptures, the Buddha learned the two

formless attainments from two teachers, Alara Kalama and Uddaka

Ramaputta respectively, prior to his enlightenment. It is most likely that they belonged to the Brahmanical tradition.

However, he realized that neither "Dimension of Nothingness" nor

"Dimension of Neither Perception nor Non-Perception" lead to Nirvana and

left. The Buddha said in the Ariyapariyesana Sutta:

But the thought occurred to me,

"This Dhamma leads not to disenchantment, to dispassion, to cessation,

to stilling, to direct knowledge, to Awakening, nor to Unbinding, but

only to reappearance in the dimension of neither perception nor

non-perception." So, dissatisfied with that Dhamma, I left.

Cessation of feelings and perceptions

The Buddha himself discovered an attainment beyond the dimension

of neither perception nor non-perception, the "cessation of feelings and

perceptions". This is sometimes called the "ninth

jhāna" in commentarial and scholarly literature.

Although the "Dimension of Nothingness" and the "Dimension of Neither

Perception nor Non-Perception" are included in the list of nine Jhanas

taught by the Buddha, they are not included in the

Noble Eightfold Path.

Noble Path number eight is "Samma Samadhi" (Right Concentration), and

only the first four Jhanas are considered "Right Concentration". If he

takes a disciple through all the Jhanas, the emphasis is on the

"Cessation of Feelings and Perceptions" rather than stopping short at

the "Dimension of Neither Perception nor Non-Perception".

In the Magga-vibhanga Sutta, the Buddha defines Right

Concentration that belongs to the concentration (samadhi) division of

the path as the first four Jhanas:

And what is right concentration?

There is the case where a monk — quite withdrawn from sensuality,

withdrawn from unskillful (mental) qualities — enters & remains in

the first Jhana: rapture & pleasure born from withdrawal,

accompanied by directed thought & evaluation. With the stilling of

directed thoughts & evaluations, he enters & remains in the

Second Jhana: rapture & pleasure born of composure, unification of

awareness free from directed thought & evaluation — internal

assurance. With the fading of rapture, he remains equanimous, mindful,

& alert, and senses pleasure with the body. He enters & remains

in the Third Jhana, of which the Noble Ones declare, 'Equanimous &

mindful, he has a pleasant abiding.' With the abandoning of pleasure

& pain — as with the earlier disappearance of elation &

distress — he enters & remains in the Fourth Jhana: purity of

equanimity & mindfulness, neither pleasure nor pain. This is called

right concentration.

The Buddha did not reject the formless attainments in and of

themselves, but instead the doctrines of his teachers as a whole, as

they did not lead to

nibbana.

He then underwent harsh ascetic practices that he eventually also

became disillusioned with. He subsequently remembered entering

jhāna as a child, and realized that, "That indeed is the path to enlightenment."

In the

suttas, the immaterial attainments are never referred to as

jhānas.

The immaterial attainments have more to do with expanding, while the

Jhanas (1-4) focus on concentration. A common translation for the term

"samadhi" is concentration. Rhys Davids and Maurice Walshe agreed that

the term ” samadhi” is not found in any pre-buddhist text. Hindu texts

later used that term to indicate the state of enlightenment. This is not

in conformity with Buddhist usage. In

The Long Discourse of the Buddha: A Translation of the Digha Nikaya (pg. 1700) Maurice Walshe wrote,

Rhys Davids also states that the

term samadhi is not found in any pre-Buddhist text. To his remarks on

the subject should be added that its subsequent use in Hindu texts to

denote the state of enlightenment is not in conformity with Buddhist

usage, where the basic meaning of concentration is expanded to cover

"meditation" in general.

Meditation was an aspect of the practice of the

yogis

in the centuries preceding the Buddha. The Buddha built upon the yogis'

concern with introspection and developed their meditative techniques,

but rejected their theories of liberation. In Buddhism,

sati and

sampajanna

are to be developed at all times, in pre-Buddhist yogic practices there

is no such injunction. A yogi in the Brahmanical tradition is not to

practice while defecating, for example, while a Buddhist monastic should

do so.

Another new teaching of the Buddha was that

meditative absorption must be combined with a liberating cognition.

Religious knowledge or "vision" was indicated as a result of

practice both within and outside the Buddhist fold. According to the

Samaññaphala Sutta this sort of vision arose for the Buddhist adept as a result of the perfection of 'meditation' (Sanskrit:

dhyāna) coupled with the perfection of 'ethics' (Sanskrit:

śīla).

Some of the Buddha's meditative techniques were shared with other

traditions of his day, but the idea that ethics are causally related to

the attainment of "religious insight" (Sanskrit:

prajñā) was original.

The Buddhist texts are probably the earliest describing meditation techniques. They describe meditative practices and states that existed before the Buddha, as well as those first developed within Buddhism. Two Upanishads written after the rise of Buddhism do contain full-fledged descriptions of

yoga as a means to liberation.

While there is no convincing evidence for meditation in

pre-Buddhist early Brahminic texts, Wynne argues that formless

meditation originated in the Brahminic or Shramanic tradition, based on

strong parallels between Upanishadic cosmological statements and the

meditative goals of the two teachers of the Buddha as recorded in the

early Buddhist texts. He mentions less likely possibilities as well. Having argued that the cosmological statements in the Upanishads also reflect a contemplative tradition, he argues that the

Nasadiya Sukta contains evidence for a contemplative tradition, even as early as the late Rg Vedic period.

Vedas

Buddhism

does not deny that the Vedas in their true origin were sacred although

it maintains that the Vedas have been amended repeatedly by certain

Brahmins to secure their positions in society. The Buddha declared that

the Veda in its true form was declared by Kashyapa to certain rishis,

who by severe penances had acquired the power to see by divine eyes. In the Buddhist

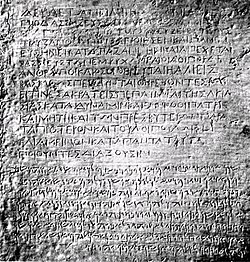

Vinaya Pitaka of the

Mahavagga (I.245) section the Buddha names these rishis. The names of the Vedic rishis were "Atthako, Vâmako, Vâmadevo,

Vessâmitto,

Yamataggi,

Angiraso,

Bhâradvâjo,

Vâsettho,

Kassapo, and

Bhagu" but that it was altered by a few Brahmins who introduced animal sacrifices. The Vinaya Pitaka's section

Anguttara Nikaya: Panchaka Nipata says that it was on this alteration of the true Veda that the Buddha refused to pay respect to the Vedas of his time.

The Buddhist text

Mahamayuri Tantra, written during 1-3rd century CE, mentions deities thrughout

Jambudvipa

(modern India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Nepal and Sri Lanka,

and invokes them for the protection of the Buddhadharma. It also

mentions a large number of Vedic rishis.

The yaksha Mahesvara resides in Virata.

Brhaspati resides in Sravasti.

The yaksha Sagara resides in Saketa.

The yaksha Vajrayudha resides in Vaisali.

Haripingala resides in Malla.

The yaksha king Mahakala resides in Varanasi.

Sudarsana resides in Campa.

The yaksha Visnu resides in Dvaraka.

The yaksha Dharani resides at Dvarapali.

The yaksha Vibhisana resides in Tamraparni.

...

These deities of virtues and great yaksha generals are located

everywhere in Jambudvipa. They uphold and protect the Buddhadharma,

generating compassion.

...

Maharishi Astamaka / Maharishi Vamaka / Maharishi Vamadeva /

Maharishi Marici / Maharishi Markandeya / Maharishi Visvamitra /

Maharishi Vasistha / Maharishi Valmika / Maharishi Kasyapa /

Maharishi Vrddhakasyapa / Maharishi Bhrgu / Maharishi Bhrngirasa /

Maharishi Angirasa / Maharishi Bhagiratha / Maharishi Atreya /

Maharishi Pulastya / Maharishi Sthulasira / Maharishi Yamadgni /

Maharishi Vaisampaya / Maharishi Krsnavaisampaya / Maharishi Harita /

Maharishi Haritaya / Maharishi Samangira / Maharishi Udgata /

Maharishi Samudgata / Maharishi Ksantivadi / Maharishi Kirtti /

Maharishi Sukirtti / Maharishi Guru / Maharishi Sarabha /

Maharishi Potalaka / Maharishi Asvalayana / Maharishi Gandhamadana /

Maharishi Himavan / Maharishi Lohitaksa / Maharishi Durvasa /

Maharishi Vaisampayana / Maharishi Valmika / Maharishi Batto /

Maharishi Namasa / Maharishi Sarava / Maharishi Manu /

Maharishi Amgiraja / Maharishi Indra / Maharishi Brhaspati /

Maharishi Sukra / Maharishi Prabha / Maharishi Suka /

Maharishi Aranemi / Maharishi Sanaiscara / Maharishi Budha /

Maharishi Janguli / Maharishi Gandhara / Maharishi Ekasrnga /

Maharishi Rsyasrnga / Maharishi Garga / Maharishi Gargyayana /

Maharishi Bhandayana / Maharishi Katyayana / Maharishi Kandyayana /

Maharishi Kapila / Maharishi Gotama / Maharishi Matanga /

Maharishi Lohitasva / Maharishi Sunetra / Maharishi Suranemi /

Maharishi Narada / Maharishi Parvata / Maharishi Krimila.

...

These sages were ancient great sages who had written the four Vedas,

proficient in mantra practices, and well-versed in all practices that

benefit themselves and others. May you on account of Mahamayuri Vidyarajni,

protect me [your name] and my loved ones, grant us longevity,

and free us from all worries and afflictions.

The Buddha is recorded in the Canki Sutta (

Majjhima Nikaya 95) as saying to a group of Brahmins:

O Vasettha, those priests who know

the scriptures are just like a line of blind men tied together where the

first sees nothing, the middle man nothing, and the last sees nothing.

In the same discourse, he says:

It is not proper for a wise man who

maintains truth to come to the conclusion: This alone is Truth, and

everything else is false.

He is also recorded as saying:

To be attached to one thing (to a

certain view) and to look down upon other things (views) as inferior –

this the wise men call a fetter.

Walpola Rahula writes, "It is always a question of knowing and seeing, and not that of believing. The teaching of the Buddha is qualified as

ehi-passika,

inviting you to 'come and see,' but not to come and believe... It is

always seeing through knowledge or wisdom, and not believing through

faith in Buddhism."

In Hinduism, philosophies are classified either as

Astika or

Nastika, that is, philosophies that either affirm or reject the authorities of the Vedas. According to this tradition, Buddhism is a

Nastika school since it rejects the authority of the Vedas. Buddhists on the whole called those who did not believe in Buddhism the "outer path-farers" (

tiirthika).

Conversion

Since the Hindu scriptures are essentially silent on the issue of

religious conversion, the issue of whether Hindus

evangelize is open to interpretations.

Those who view Hinduism as an ethnicity more than as a religion tend

to believe that to be a Hindu, one must be born a Hindu. However, those

who see Hinduism primarily as a philosophy, a set of beliefs, or a way

of life generally believe that one can convert to Hinduism by

incorporating Hindu beliefs into one's life and by considering oneself a

Hindu.

The Supreme Court of India has taken the latter view, holding that the

question of whether a person is a Hindu should be determined by the

person's belief system, not by their ethnic or racial heritage.

Buddhism spread throughout Asia via evangelism and conversion.

Buddhist scriptures depict such conversions in the form of lay

followers declaring their support for the Buddha and his teachings, or

via ordination as a Buddhist monk. Buddhist identity has been broadly

defined as one who "takes

refuge" in the Buddha, Dharma, and

Sangha,

echoing a formula seen in Buddhist texts. In some communities, formal

conversion rituals are observed. No specific ethnicity has typically

been associated with Buddhism, and as it spread beyond its origin in

India immigrant monastics were replaced with newly ordained members of

the local ethnic or tribal group.

Soteriology

Upanishadic

soteriology is focused on the static Self, while the Buddha's is

focused on dynamic agency. In the former paradigm, change and movement

are an illusion; to realize the Self as the only reality is to realize

something that has always been the case. In the Buddha's system by

contrast, one has to make things happen.

The fire metaphor used in the

Aggi-Vacchagotta Sutta

(which is also used elsewhere) is a radical way of making the point

that the liberated sage is beyond phenomenal experience. It also makes

the additional point that this indefinable, transcendent state is the

sage's state even during life. This idea goes against the early

Brahminic notion of liberation at death.

Liberation for the Brahminic yogin was thought to be the permanent realization at death of a

nondual meditative state

anticipated in life. In fact, old Brahminic metaphors for the

liberation at death of the yogic adept ("becoming cool", "going out")

were given a new meaning by the Buddha; their point of reference became

the sage who is liberated in life.

The Buddha taught that these meditative states alone do not offer a

decisive and permanent end to suffering either during life or after

death.

He stated that achieving a formless attainment with no further

practice would only lead to temporary rebirth in a formless realm after

death.

Moreover, he gave a pragmatic refutation of early Brahminical theories

according to which the meditator, the meditative state, and the proposed

uncaused, unborn, unanalyzable Self, are identical.

These theories are undergirded by the Upanishadic correspondence

between macrocosm and microcosm, from which perspective it is not

surprising that meditative states of consciousness were thought to be

identical to the subtle strata of the cosmos.

The Buddha, in contrast, argued that states of consciousness come about

caused and conditioned by the yogi's training and techniques, and

therefore no state of consciousness could be this eternal Self.

Nonduality

Both

the Buddha's conception of the liberated person and the goal of early

Brahminic yoga can be characterized as nondual, but in different ways.

The nondual goal in early Brahminism was conceived in

ontological

terms; the goal was that into which one merges after death. According

to Wynne, liberation for the Buddha "... is nondual in another, more

radical, sense. This is made clear in the dialogue with Upasiva, where

the liberated sage is defined as someone who has passed beyond

conceptual dualities. Concepts that might have some meaning in ordinary

discourse, such as consciousness or the lack of it, existence and

non-existence, etc., do not apply to the sage. For the Buddha,

propositions are not applicable to the liberated person, because

language and concepts (

Sn 1076:

vaadapathaa,

dhammaa), as well as any sort of intellectual reckoning (

sankhaa) do not apply to the liberated sage.

Nirvana

Nirvana

(or Nibbana in Pali language) means literally 'blowing out' or

'quenching'. The term is pre-Buddhist, but its etymology is not

essentially conclusive for finding out its exact meaning as the highest

goal of early Buddhism.

It must be kept in mind that nirvana is one of many terms for salvation

that occur in the orthodox Buddhist scriptures. Other terms that appear

are 'Vimokha', or 'Vimutti', implying 'salvation' and 'deliverance'

respectively. Some more words synonymously used for

nirvana in Buddhist scriptures are 'mokkha/

moksha', meaning 'liberation' and 'kevala/kaivalya', meaning 'wholeness'; these words were given a new Buddhist meaning.

The concept of Nirvana has been also found among other religions such as Hinduism, Jainism, and

Sikhism.

Early Buddhism and early Vedanta

Early Buddhist scriptures

do not mention schools of learning directly connected with the

Upanishads. Though the earliest Upanishads had been completed by the

Buddha's time, they are not cited in the early Buddhist texts as

Upanishads or Vedanta. For the early Buddhists they were likely not

thought of as having any outstanding significance in and of themselves,

and as simply one section of the Vedas.

The Buddhist texts do describe wandering, mendicant Brahmins who

appear to have valued the early Upanishads' promotion of this lifestyle

as opposed to living the life of the householder and accruing wealth

from nobles in exchange for performing Vedic sacrifices.

Furthermore, the early Buddhist texts mention ideas similar to those

expounded in the early Upanishads, before controverting them.

Brahman

The old

Upanishads largely consider Brahman (masculine gender, Brahmā in the

nominative case, henceforth "Brahmā") to be a personal god, and

Brahman (neuter gender, Brahma in the nominative case, henceforth "Brahman") to be the impersonal world principle. They do not strictly distinguish between the two, however.

The old Upanishads ascribe these characteristics to Brahmā: first, he

has light and luster as his marks; second, he is invisible; third, he is

unknowable, and it is impossible to know his nature; fourth, he is

omniscient. The old Upanishads ascribe these characteristics to Brahman

as well.

In the Buddhist texts, there are many

Brahmās.

There they form a class of superhuman beings, and rebirth into the

realm of Brahmās is possible by pursuing Buddhist practices.

In the

Pāli scriptures, the neuter Brahman does not appear (though the word

brahma is standardly used in compound words to mean "best", or "supreme"),

however ideas are mentioned as held by various Brahmins in connection

with Brahmā that match exactly with the concept of Brahman in the

Upanishads. Brahmins who appear in the Tevijja-suttanta of the Digha

Nikaya regard "union with Brahmā" as liberation, and earnestly seek it.

In that text, Brahmins of the time are reported to assert: "Truly every

Brahmin versed in the three Vedas has said thus: 'We shall expound the

path for the sake of union with that which we do not know and do not

see. This is the correct path. This path is the truth, and leads to

liberation. If one practices it, he shall be able to enter into

association with Brahmā." The early Upanishads frequently expound

"association with Brahmā", and "that which we do not know and do not

see" matches exactly with the early Upanishadic Brahman.

In the earliest Upanishad, the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, the

Absolute, which came to be referred to as Brahman, is referred to as "the imperishable".

The Pāli scriptures present a "pernicious view" that is set up as an

absolute principle corresponding to Brahman: "O Bhikkhus! At that time

Baka, the Brahmā, produced the following pernicious view: 'It is

permanent. It is eternal. It is always existent. It is independent

existence. It has the dharma of non-perishing. Truly it is not born,

does not become old, does not die, does not disappear, and is not born

again. Furthermore, no liberation superior to it exists elsewhere." The

principle expounded here corresponds to the concept of Brahman laid out

in the Upanishads. According to this text the Buddha criticized this

notion: "Truly the Baka Brahmā is covered with unwisdom."

Gautama Buddha confined himself to what is empirically given.

This empiricism is based broadly on both ordinary sense experience and

extrasensory perception enabled by high degrees of mental

concentration.

Ātman

Ātman

is a Sanskrit word that means 'self'. A major departure from Hindu and

Jain philosophy is the Buddhist rejection of a permanent, self-existent

soul (Ātman) in favour of

anicca or impermanence.

In

Hindu philosophy, especially in the

Vedanta school of

Hinduism, Ātman is the

first principle, the

true self of an individual beyond identification with phenomena, the essence of an individual.

Yajnavalkya (c. 9th century BCE), in the

Brihadaranyaka Upanishad,

uses the word to indicate that in which everything exists, which is of

the highest value, which permeates everything, which is the essence of

all, bliss and beyond description. While, older Upanishads such as the Brihadaranyaka, mention several times that the Self is described as

Neti neti or not this – not this, Upanishads post

Buddhism, like the

Maitri Upanishad, define Ātman as only the defiled individual self, rather than the universal self.

Taittiriya Upanishad defines Ātman or the

Self as consisting of five

sheaths

(kosha): the bodily self consisting of the essence of food (annamaya

kosha), the vital breath (pranamaya kosha), the mind or will (manomaya

kosha), the intellect or capacity to know (vijnanamaya kosha) and bliss (

anandamaya kosha). Knowledge or realization of the Ātman is seen as essential to attain salvation (

liberation):

If atman is brahman in a pot (the

body), then one need merely break the pot to fully realize the

primordial unity of the individual soul with the plenitude of Being that

was the Absolute.

Schools of

Indian philosophy, such as

Advaita (non-dualism) see Ātman within each living entity as being fully identical with

Brahman – the Principle, whereas other schools such as

Dvaita (dualism) differentiate between the individual atma in living beings, and the Supreme atma (

Paramatma) as being at least partially separate beings. Unlike

Advaita,

Samkhya holds blissfullness of Ātman as merely figurative. However, both Samkhya and Advaita consider the ego (asmita,

ahamkara) rather than the Ātman to be the cause of pleasure and pain. Later Advaitic text

Pañcadaśī

classifies the degrees of Ātman under three headings: Gauna or

secondary (anything other than the personality that an individual

identifies with), Mithya or false (bodily personality) and Mukhya or

primary (the real Self).

The concept of Ātman was rejected by the Buddha. Terms like

anatman (not-self) and

shunyata

(voidness) are at the core of all Buddhist traditions. The permanent

transcendence of the belief in the separate existence of the self is

integral to the enlightenment of an

Arhat. The Buddha criticized conceiving theories even of a unitary soul or identity immanent in all things as unskillful.

In fact, according to the Buddha's statement in Khandha Samyutta 47,

all thoughts about self are necessarily, whether the thinker is aware of

it or not, thoughts about the five

aggregates or one of them.

Despite the rejection of Ātman by Buddhists there were

similarities between certain concepts in Buddhism and Ātman. The

Upanishadic "Self" shares certain characteristics with

nibbana; both are permanent, beyond suffering, and unconditioned. Buddhist mysticism is also of a different sort from that found in systems revolving around the concept of a "God" or "Self":

If one would characterize the forms

of mysticism found in the Pali discourses, it is none of the nature-,

God-, or soul-mysticism of F.C. Happold. Though nearest to the latter,

it goes beyond any ideas of 'soul' in the sense of immortal 'self' and

is better styled 'consciousness-mysticism'.

However, the Buddha shunned any attempt to see the spiritual goal in

terms of "Self" because in his framework, the craving for a permanent

self is the very thing that keeps a person in the round of

uncontrollable rebirth, preventing him or her from attaining nibbana. At the time of the Buddha some philosophers and meditators posited a

root:

an abstract principle all things emanated from and that was immanent in

all things. When asked about this, instead of following this pattern of

thinking, the Buddha attacks it at its very root: the notion of a

principle in the abstract, superimposed on experience. In contrast, a

person in training should look for a different kind of "root" — the root

of

dukkha

experienced in the present. According to one Buddhist scholar, theories

of this sort have most often originated among meditators who label a

particular meditative experience as the ultimate goal, and identify with

it in a subtle way.

Adi Shankara in his

works

refuted the Buddhist arguments against Ātman. He suggested that a

self-evident conscious agent would avoid infinite regress, since there

would be no necessity to posit another agent who would know this. He

further argued that a cognizer beyond cognition could be easily

demonstrated from the diversity in self existence of the witness and the

notion.

Furthermore, Shankara thought that no doubts could be raised about the

Self, for the act of doubting implies at the very least the existence of

the doubter.

Vidyaranya, another Advaita Vedantic philosopher, expresses this argument as:

No one can doubt the fact of his own existence. Were one to do so, who would the doubter be?

Cosmic Self declared non-existent

The Buddha denies the existence of the cosmic Self, as conceived in the Upanishadic tradition, in the Alagaddupama Sutta (

M I 135-136). Possibly the most famous Upanishadic dictum is

tat tvam asi, "thou art that." Transposed into first person, the

Pali version is

eso ‘ham asmi,

"I am this." This is said in several suttas to be false. The full

statement declared to be incorrect is "This is mine, I am this, this is

my self/essence." This is often rejected as a wrong view.

The Alagaduppama Sutta rejects this and other obvious echoes of

surviving Upanishadic statements as well (these are not mentioned as

such in the commentaries, and seem not to have been noticed until modern

times). Moreover, the passage denies that one’s self is the same as the

world and that one will become the world self at death. The Buddha tells the monks that people worry about something that is non-existent externally (

bahiddhaa asati) and non-existent internally (

ajjhattam asati); he is referring respectively to the soul/essence of the world and of the individual. A similar rejection of "internal" Self and "external" Self occurs at AN II 212. Both are referring to the Upanishads.

The most basic presupposition of early Brahminic cosmology is the

identification of man and the cosmos (instances of this occur at

TU II.1 and

Mbh

XII.195), and liberation for the yogin was thought to only occur at

death, with the adept's union with brahman (as at Mbh XII.192.22).

The Buddha's rejection of these theories is therefore one instance of

the Buddha's attack on the whole enterprise of Upanishadic ontology.

Brahman

The

Buddha redefined the word "brahman" so as to become a synonym for

arahant, replacing a distinction based on birth with one based on

spiritual attainment.

The early Buddhist scriptures furthermore defined purity as determined

by one's state of mind, and refer to anyone who behaves unethically, of

whatever caste, as "rotting within", or "a rubbish heap of impurity".

The Buddha explains his use of the word

brahman in many places. At

Sutta Nipata 1.7

Vasala Sutta,

verse 12, he states: "Not by birth is one an outcast; not by birth is

one a brahmin. By deed one becomes an outcast, by deed one becomes a

brahman." An entire chapter of the

Dhammapada is devoted to showing how a true brahman in the Buddha's use of the word is one who is of totally pure mind, namely, an

arahant.

However, it is very noteworthy that the Bhagavad Gita also defines

Brahmin, and other varnas, as qualities and resulting from actions, and

does not mention birth as a factor in determining these. In that regard,

the chapter on Brahmins in the Dhammapada may be regarded as being

entirely in tune with the definition of a Brahmin in Chapter 18 of the

Bhagavad Gita. Both say that a Brahmin is a person having certain

qualities.

A defining of feature of the Buddha's teachings is

self-sufficiency, so much so as to render the Brahminical priesthood

entirely redundant.

Buddha in Hindu scriptures

Hinduism regards Buddha (bottom right) as one of the 10 avatars of Vishnu.

In one Purana, the Buddha is described as an incarnation of Vishnu who incarnated in order to delude

demons away from the Vedic dharma. The

Bhavishya Purana posits:

At this time, reminded of the Kali Age, the god Vishnu became born as Gautama, the Shakyamuni,

and taught the Buddhist dharma for ten years. Then Shuddodana ruled for

twenty years, and Shakyasimha for twenty. At the first stage of the Kali Age, the path of the Vedas was destroyed and all men became Buddhists. Those who sought refuge with Vishnu were deluded.

Consequently, the word

Buddha is mentioned in several of the

Puranas that are believed to have been composed after his birth.

Buddha in Buddhist scriptures

According to the biography of the Buddha, he was a Mahapurusha (great being) named Shvetaketu.

Tushita Heaven (Home of the Contented gods) was the name of the realm he dwells before taking his last birth on earth as

Gautama Buddha. There is no more rebirth for a Buddha. Before leaving the Tushita realm to take birth on earth, he designated

Maitreya to take his place there. Maitreya will come to earth as the next Buddha, instead of him coming back again.

Krishna was a past life of

Sariputra, a chief disciple of the Buddha.

He has not attained enlightenment during that life as Krishna.

Therefore, he came back to be reborn during the life of the Buddha and

reached the first stage of Enlightenment after encountering an

enlightened disciple of the Buddha. He reached full Arahantship or full

Awakening after became ordained in the Buddha's sangha.

Notable views

Neo-Vedanta

Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan has claimed that the Buddha did not look upon himself as an innovator, but only a restorer of the way of the

Upanishads,

despite the fact that the Buddha did not accept the Upanishads, viewing

them as comprising a pretentious tradition, foreign to his paradigm.

Vivekananda wrote in glowing terms about Buddha, and visited

Bodh Gaya several times.

Steven Collins sees such Hindu claims regarding Buddhism as part

of an effort – itself a reaction to Christian proselytizing efforts in

India – to show that "all religions are one", and that Hinduism is

uniquely valuable because it alone recognizes this fact.

Reformation

Some scholars have written that Buddhism should be regarded as "reformed Brahmanism", and many Hindus consider Buddhism a sect of Hinduism.

Dalit-movement

B. R. Ambedkar, the founder of the

Dalit Buddhist movement, declared that Buddhism offered an opportunity for low-caste and

untouchable

Hindus to achieve greater respect and dignity because of its non-caste

doctrines. Among the 22 vows he prescribed to his followers is an

injunction against having faith in

Brahma, Vishnu and

Mahesh. He also regarded the belief that the Buddha was an incarnation of Vishnu as "false propaganda".

Hindu-Buddhist temples

Many examples exist of temples dedicated to both faiths. These include the

Kaiyuan Temple and

Angkor Wat.