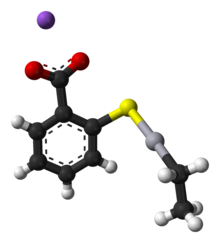

Chemical structure of retinol, one of the major forms of vitamin A

Vitamin A is a group of unsaturated nutritional organic compounds that includes retinol, retinal, retinoic acid, and several provitamin A carotenoids (most notably beta-carotene). Vitamin A has multiple functions: it is important for growth and development, for the maintenance of the immune system and good vision. Vitamin A is needed by the retina of the eye in the form of retinal, which combines with protein opsin to form rhodopsin, the light-absorbing molecule necessary for both low-light (scotopic vision) and color vision.

Vitamin A also functions in a very different role as retinoic acid (an

irreversibly oxidized form of retinol), which is an important hormone-like growth factor for epithelial and other cells.

In foods of animal origin, the major form of vitamin A is an ester, primarily retinyl palmitate, which is converted to retinol (chemically an alcohol) in the small intestine. The retinol form functions as a storage form of the vitamin, and can be converted to and from its visually active aldehyde form, retinal.

All forms of vitamin A have a beta-ionone ring to which an isoprenoid chain is attached, called a retinyl group. Both structural features are essential for vitamin activity. The orange pigment of carrots

(beta-carotene) can be represented as two connected retinyl groups,

which are used in the body to contribute to vitamin A levels. Alpha-carotene and gamma-carotene

also have a single retinyl group, which give them some vitamin

activity. None of the other carotenes have vitamin activity. The

carotenoid beta-cryptoxanthin possesses an ionone group and has vitamin activity in humans.

Vitamin A can be found in two principal forms in foods:

- Retinol, the form of vitamin A absorbed when eating animal food sources, is a yellow, fat-soluble substance. Since the pure alcohol form is unstable, the vitamin is found in tissues in a form of retinyl ester. It is also commercially produced and administered as esters such as retinyl acetate or palmitate.

- The carotenes alpha-carotene, beta-carotene, gamma-carotene; and the xanthophyll beta-cryptoxanthin (all of which contain beta-ionone rings), but no other carotenoids, function as provitamin A in herbivores and omnivore animals, which possess the enzyme beta-carotene 15,15'-dioxygenase which cleaves beta-carotene in the intestinal mucosa and converts it to retinol.

Medical use

Deficiency

Vitamin A deficiency is estimated to affect approximately one third of children under the age of five around the world. It is estimated to claim the lives of 670,000 children under five annually.

Approximately 250,000–500,000 children in developing countries become

blind each year owing to vitamin A deficiency, with the highest

prevalence in Southeast Asia and Africa. Vitamin A deficiency is "the leading cause of preventable childhood blindness," according to UNICEF.

It also increases the risk of death from common childhood conditions

such as diarrhea. UNICEF regards addressing vitamin A deficiency as

critical to reducing child mortality, the fourth of the United Nations' Millennium Development Goals.

Vitamin A deficiency can occur as either a primary or a secondary

deficiency. A primary vitamin A deficiency occurs among children and

adults who do not consume an adequate intake of provitamin A carotenoids

from fruits and vegetables or preformed vitamin A from animal and dairy

products. Early weaning from breastmilk can also increase the risk of

vitamin A deficiency.

Secondary vitamin A deficiency is associated with chronic

malabsorption of lipids, impaired bile production and release, and

chronic exposure to oxidants, such as cigarette smoke, and chronic

alcoholism. Vitamin A is a fat-soluble vitamin and depends on micellar

solubilization for dispersion into the small intestine, which results in

poor use of vitamin A from low-fat diets.

Zinc deficiency can also impair absorption, transport, and metabolism

of vitamin A because it is essential for the synthesis of the vitamin A

transport proteins and as the cofactor in conversion of retinol to

retinal. In malnourished populations, common low intakes of vitamin A

and zinc increase the severity of vitamin A deficiency and lead

physiological signs and symptoms of deficiency. A study in Burkina Faso showed major reduction of malaria morbidity with combined vitamin A and zinc supplementation in young children.

Due to the unique function of retinal as a visual chromophore,

one of the earliest and specific manifestations of vitamin A deficiency

is impaired vision, particularly in reduced light – night blindness.

Persistent deficiency gives rise to a series of changes, the most

devastating of which occur in the eyes. Some other ocular changes are

referred to as xerophthalmia. First there is dryness of the conjunctiva (xerosis)

as the normal lacrimal and mucus-secreting epithelium is replaced by a

keratinized epithelium. This is followed by the build-up of keratin

debris in small opaque plaques (Bitot's spots) and, eventually, erosion of the roughened corneal surface with softening and destruction of the cornea (keratomalacia) and leading to total blindness.

Other changes include impaired immunity (increased risk of ear

infections, urinary tract infections, Meningococcal disease),

hyperkeratosis (white lumps at hair follicles), keratosis pilaris and squamous metaplasia

of the epithelium lining the upper respiratory passages and urinary

bladder to a keratinized epithelium. In relation to dentistry, a

deficiency in vitamin A may lead to enamel hypoplasia.

Adequate supply, but not excess vitamin A, is especially

important for pregnant and breastfeeding women for normal fetal

development and in breastmilk. Deficiencies cannot be compensated by postnatal supplementation. Excess vitamin A, which is most common with high dose vitamin supplements, can cause birth defects and therefore should not exceed recommended daily values.

Vitamin A metabolic inhibition as a result of alcohol consumption

during pregnancy is one proposed mechanism for fetal alcohol syndrome

and is characterized by teratogenicity resembling maternal vitamin A

deficiency or reduced retinoic acid synthesis during embryogenesis.

Vitamin A supplementation

A

2012 systematic review found no evidence that beta-carotene or vitamin A

supplements increase longevity in healthy people or in people with

various diseases.

A meta-analysis of 43 studies showed that vitamin A supplementation of

children under five who are at risk of deficiency reduced mortality by

up to 24%.

However, a 2016 Cochrane review concluded there was not evidence to

recommend blanket Vitamin A supplementation for all infants between one

and six months of age, as it did not reduce infant mortality or

morbidity in low- and middle-income countries. The World Health Organization estimated that vitamin A supplementation averted 1.25 million deaths due to vitamin A deficiency in 40 countries since 1998.

In 2008, it was estimated that an annual investment of US$60 million in

vitamin A and zinc supplementation combined would yield benefits of

more than US$1 billion per year, with every dollar spent generating

benefits of more than US$17.

While strategies include intake of vitamin A through a

combination of breast feeding and dietary intake, delivery of oral

high-dose supplements remain the principal strategy for minimizing

deficiency.

About 75% of the vitamin A required for supplementation activity by

developing countries is supplied by the Micronutrient Initiative with

support from the Canadian International Development Agency. Food fortification approaches are feasible, but cannot ensure adequate intake levels.

Observational studies of pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa have

shown that low serum vitamin A levels are associated with an increased

risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV. Low blood vitamin A levels

have been associated with rapid HIV infection and deaths.

Reviews of clinical studies on the possible mechanisms of HIV

transmission found no relationship between blood vitamin A levels in the

mother and infant, with conventional intervention established by

treatment with anti-HIV drugs.

Side effects

Since vitamin A is fat-soluble, disposing of any excesses taken in

through diet takes much longer than with water-soluble B vitamins and

vitamin C. This allows for toxic levels of vitamin A to accumulate.

These toxicities only occur with preformed (retinoid) vitamin A (such as

from liver). The carotenoid forms (such as beta-carotene as found in

carrots), give no such symptoms, but excessive dietary intake of

beta-carotene can lead to carotenodermia, a harmless but cosmetically displeasing orange-yellow discoloration of the skin.

In general, acute toxicity occurs at doses of 25,000 IU/kg of body weight, with chronic toxicity occurring at 4,000 IU/kg of body weight daily for 6–15 months. However, liver toxicities can occur at levels as low as 15,000 IU (4500 micrograms) per day to 1.4 million IU per day, with an average daily toxic dose of 120,000 IU, particularly with excessive consumption of alcohol. In people with renal failure, 4000 IU can cause substantial damage. Signs of toxicity may occur with long-term consumption of vitamin A at doses of 25,000–33,000 IU per day.

Excessive vitamin A consumption can lead to nausea, irritability, anorexia

(reduced appetite), vomiting, blurry vision, headaches, hair loss,

muscle and abdominal pain and weakness, drowsiness, and altered mental

status. In chronic cases, hair loss, dry skin, drying of the mucous

membranes, fever, insomnia,

fatigue, weight loss, bone fractures, anemia, and diarrhea can all be

evident on top of the symptoms associated with less serious toxicity. Some of these symptoms are also common to acne treatment with Isotretinoin. Chronically high doses of vitamin A, and also pharmaceutical retinoids such as 13-cis retinoic acid, can produce the syndrome of pseudotumor cerebri.

This syndrome includes headache, blurring of vision and confusion,

associated with increased intracerebral pressure. Symptoms begin to

resolve when intake of the offending substance is stopped.

Chronic intake of 1500 RAE of

preformed vitamin A may be associated with osteoporosis and hip

fractures because it suppresses bone building while simultaneously

stimulating bone breakdown, although other reviews have disputed this effect, indicating further evidence is needed.

A 2012 systematic review found that beta-carotene and higher

doses of supplemental vitamin A increased mortality in healthy people

and people with various diseases. The findings of the review extend evidence that antioxidants may not have long-term benefits.

Equivalencies of retinoids and carotenoids (IU)

As

some carotenoids can be converted into vitamin A, attempts have been

made to determine how much of them in the diet is equivalent to a

particular amount of retinol, so that comparisons can be made of the

benefit of different foods. The situation can be confusing because the

accepted equivalences have changed. For many years, a system of

equivalencies in which an international unit (IU) was equal to 0.3 μg of retinol, 0.6 μg of β-carotene, or 1.2 μg of other provitamin-A carotenoids was used.

Later, a unit called retinol equivalent (RE) was introduced. Prior to

2001, one RE corresponded to 1 μg retinol, 2 μg β-carotene dissolved in

oil (it is only partly dissolved in most supplement pills, due to very

poor solubility in any medium), 6 μg β-carotene in normal food (because

it is not absorbed as well as when in oils), and 12 μg of either α-carotene, γ-carotene, or β-cryptoxanthin in food.

Newer research has shown that the absorption of provitamin-A

carotenoids is only half as much as previously thought. As a result, in

2001 the US Institute of Medicine

recommended a new unit, the retinol activity equivalent (RAE). Each μg

RAE corresponds to 1 μg retinol, 2 μg of β-carotene in oil, 12 μg of "dietary" beta-carotene, or 24 μg of the three other dietary provitamin-A carotenoids.

| Substance and its chemical environment | Proportion of retinol equivalent to substance (μg/μg) |

|---|---|

| Retinol | 1 |

| beta-Carotene, dissolved in oil | 1/2 |

| beta-Carotene, common dietary | 1/12 |

| alpha-Carotene, common dietary | 1/24 |

| gamma-Carotene, common dietary | 1/24 |

| beta-Cryptoxanthin, common dietary | 1/24 |

Because the conversion of retinol from provitamin carotenoids by the

human body is actively regulated by the amount of retinol available to

the body, the conversions apply strictly only for vitamin A-deficient

humans.

The absorption of provitamins depends greatly on the amount of lipids

ingested with the provitamin; lipids increase the uptake of the

provitamin.

A sample vegan diet for one day that provides sufficient vitamin A has been published by the Food and Nutrition Board (page 120). Reference values for retinol or its equivalents, provided by the National Academy of Sciences, have decreased. The RDA

(for men) established in 1968 was 5000 IU (1500 μg retinol). In 1974,

the RDA was revised to 1000 RE (1000 μg retinol). As of 2001, the RDA

for adult males is 900 RAE (900 μg or 3000 IU retinol).

By RAE definitions, this is equivalent to 1800 μg of β-carotene

supplement dissolved in oil (3000 IU) or 10800 μg of β-carotene in food

(18000 IU).

Dietary recommendations

The

U.S. Institute of Medicine (IOM) updated Estimated Average Requirements

(EARs) and Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) for vitamin A in 2001.

For infants up to 12 months there was not sufficient information to

establish a RDA, so Adequate Intake (AI) shown instead. As for safety

the IOM sets tolerable upper intake levels (ULs) for vitamins and minerals when evidence is sufficient. Collectively the EARs, RDAs, AIs and ULs are referred to as Dietary Reference Intakes

(DRIs). The calculation of retinol activity equivalents (RAE) is each

μg RAE corresponds to 1 μg retinol, 2 μg of β-carotene in oil, 12 μg of

"dietary" beta-carotene, or 24 μg of the three other dietary

provitamin-A carotenoids.

| Life stage group |

U.S. RDAs or Adequate Intakes, AI, retinol activity equivalents (μg/day) |

Upper limits, UL* (μg/day) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infants | 0–6 months | 400 (AI) | 500 (AI) |

| 7–12 months | 600 | 600 | |

| Children | 1–3 years | 300 | 600 |

| 4–8 years | 400 | 900 | |

| Males | 9–13 years | 600 | 1700 |

| 14–18 years | 900 | 2800 | |

| >19 years | 900 | 3000 | |

| Females | 9–13 years | 600 | 1700 |

| 14–18 years | 700 | 2800 | |

| >19 years | 700 | 3000 | |

| Pregnancy | <19 span="" years=""> | 750 | 2800 |

| >19 years | 770 | 3000 | |

| Lactation | <19 span="" years=""> | 1200 | 2800 |

| >19 years | 1300 | 3000 | |

- ULs are for natural and synthetic retinol ester forms of vitamin A. Beta-carotene and other provitamin A carotenoids from foods and dietary supplements are not added when calculating total vitamin A intake for safety assessments, although they are included as RAEs for RDA and AI calculations.

For U.S. food and dietary supplement labeling purposes the amount in a

serving is expressed as a percent of Daily Value (%DV). For vitamin A

labeling purposes 100% of the Daily Value was set at 5,000 IU, but on

May 27, 2016 it was revised to 900 μg RAE. A table of the pre- and post- adult Daily Values is provided at Reference Daily Intake. The deadline to be in compliance was set at January 1, 2020 for large companies and January 1, 2021 for small companies.

The European Food Safety Authority

(EFSA) refers to the collective set of information as Dietary Reference

Values, with Population Reference Intake (PRI) instead of RDA, and

Average Requirement instead of EAR. AI and UL defined the same as in

United States. For women and men ages 15 and older the PRIs are set at

650 and 750 μg/day, respectively. PRI for pregnancy is 700 μg/day, for

lactation 1300/day. For children ages 1–14 years the PRIs increase with

age from 250 to 600 μg/day. These PRIs are similar to the U.S. RDAs. The European Food Safety Authority reviewed the same safety question as the United States and set a UL at 3000 μg/day.

Sources

Carrots are a source of beta-carotene

Vitamin A is found in many foods, including the following list. Bracketed values are retinol activity equivalences (RAEs) and percentage of the adult male RDA, per 100 grams

of the foodstuff (average). Conversion of carotene to retinol varies

from person to person and bioavailability of carotene in food varies.

| Source | Retinol activity equivalences (RAEs) (in μg) |

Percentage of the adult male RDA per 100 g of the foodstuff |

|---|---|---|

| cod liver oil | 30000 | 3333% |

| liver turkey | 8058 | 895% |

| liver beef, pork, fish | 6500 | 722% |

| liver chicken | 3296 | 366% |

| ghee | 3069 | 344% |

| sweet potato | 961 | 107% |

| carrot | 835 | 93% |

| broccoli leaf | 800 | 89% |

| butter | 684 | 76% |

| kale | 681 | 76% |

| collard greens frozen then boiled | 575 | 64% |

| butternut squash | 532 | 67% |

| dandelion greens | 508 | 56% |

| spinach | 469 | 52% |

| pumpkin | 426 | 43% |

| collard greens | 333 | 37% |

| cheddar cheese | 265 | 29% |

| cantaloupe melon | 169 | 19% |

| bell pepper/capsicum, red | 157 | 17% |

| egg | 140 | 16% |

| apricot | 96 | 11% |

| papaya | 55 | 6% |

| tomatoes | 42 | 5% |

| mango | 38 | 4% |

| pea | 38 | 4% |

| broccoli florets | 31 | 3% |

| milk | 28 | 3% |

| bell pepper/capsicum, green | 18 | 2% |

| spirulina | 3 | 0.3% |

Metabolic functions

Vitamin A plays a role in a variety of functions throughout the body, such as:

- Vision

- Gene transcription

- Immune function

- Embryonic development and reproduction

- Bone metabolism

- Haematopoiesis

- Skin and cellular health

- Teeth

- Mucous membrane

Vision

The role of vitamin A in the visual cycle is specifically related to the retinal form. Within the eye, 11-cis-retinal is bound to the protein "opsin" to form rhodopsin in rods and iodopsin (cones) at conserved lysine residues. As light enters the eye, the 11-cis-retinal

is isomerized to the all-"trans" form. The all-"trans" retinal

dissociates from the opsin in a series of steps called photo-bleaching.

This isomerization induces a nervous signal along the optic nerve to the

visual center of the brain. After separating from opsin, the

all-"trans"-retinal is recycled and converted back to the

11-"cis"-retinal form by a series of enzymatic reactions. In addition,

some of the all-"trans" retinal may be converted to all-"trans" retinol

form and then transported with an interphotoreceptor retinol-binding

protein (IRBP) to the pigment epithelial cells. Further esterification

into all-"trans" retinyl esters allow for storage of all-trans-retinol

within the pigment epithelial cells to be reused when needed. The final stage is conversion of 11-cis-retinal

will rebind to opsin to reform rhodopsin (visual purple) in the retina.

Rhodopsin is needed to see in low light (contrast) as well as for night

vision. Kühne showed that rhodopsin in the retina is only regenerated

when the retina is attached to retinal pigmented epithelium,

which provides retinal. It is for this reason that a deficiency in

vitamin A will inhibit the reformation of rhodopsin and lead to one of

the first symptoms, night blindness.

Gene transcription

Vitamin A, in the retinoic acid form, plays an important role in gene

transcription. Once retinol has been taken up by a cell, it can be

oxidized to retinal (retinaldehyde) by retinol dehydrogenases and then

retinaldehyde can be oxidized to retinoic acid by retinaldehyde

dehydrogenases.

The conversion of retinaldehyde to retinoic acid is an irreversible

step, meaning that the production of retinoic acid is tightly regulated,

due to its activity as a ligand for nuclear receptors.

The physiological form of retinoic acid (all-trans-retinoic acid)

regulates gene transcription by binding to nuclear receptors known as

retinoic acid receptors (RARs) which are bound to DNA as heterodimers

with retinoid "X" receptors (RXRs). RAR and RXR must dimerize before

they can bind to the DNA. RAR will form a heterodimer with RXR

(RAR-RXR), but it does not readily form a homodimer (RAR-RAR). RXR, on

the other hand, may form a homodimer (RXR-RXR) and will form

heterodimers with many other nuclear receptors as well, including the

thyroid hormone receptor (RXR-TR), the Vitamin D3 receptor (RXR-VDR), the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (RXR-PPAR) and the liver "X" receptor (RXR-LXR).

The RAR-RXR heterodimer recognizes retinoic acid response

elements (RAREs) on the DNA whereas the RXR-RXR homodimer recognizes

retinoid "X" response elements (RXREs) on the DNA; although several

RAREs near target genes have been shown to control physiological

processes,

this has not been demonstrated for RXREs. The heterodimers of RXR with

nuclear receptors other than RAR (i.e. TR, VDR, PPAR, LXR) bind to

various distinct response elements on the DNA to control processes not

regulated by vitamin A.

Upon binding of retinoic acid to the RAR component of the RAR-RXR

heterodimer, the receptors undergo a conformational change that causes

co-repressors to dissociate from the receptors. Coactivators can then

bind to the receptor complex, which may help to loosen the chromatin

structure from the histones or may interact with the transcriptional

machinery. This response can upregulate (or downregulate) the expression of target genes, including Hox genes as well as the genes that encode for the receptors themselves (i.e. RAR-beta in mammals).

Immune function

Vitamin A plays a role in many areas of the immune system, particularly in T cell differentiation and proliferation.

Vitamin A promotes the proliferation of T cells through an indirect mechanism involving an increase in IL-2. In addition to promoting proliferation, Vitamin A, specifically retinoic acid, influences the differentiation of T cells. In the presence of retinoic acid, dendritic cells located in the gut are able to mediate the differentiation of T cells into regulatory T cells.

Regulatory T cells are important for prevention of an immune response

against "self" and regulating the strength of the immune response in

order to prevent host damage. Together with TGF-β, Vitamin A promotes the conversion of T cells to regulatory T cells. Without Vitamin A, TGF-β stimulates differentiation into T cells that could create an autoimmune response.

Hematopoietic stem cells

are important for the production of all blood cells, including immune

cells, and are able to replenish these cells throughout the life of an

individual. Dormant hematopoietic stem cells are able to self-renew and

are available to differentiate and produce new blood cells when they are

needed. In addition to T cells, Vitamin A is important for the correct

regulation of hematopoietic stem cell dormancy.

When cells are treated with all-trans retinoic acid, they are unable to

leave the dormant state and become active, however, when vitamin A is

removed from the diet, hematopoietic stem cells are no longer able to

become dormant and the population of hematopoietic stem cells decreases.

This shows an importance in creating a balanced amount of vitamin A

within the environment to allow these stem cells to transition between a

dormant and activated state, in order to maintain a healthy immune

system.

Vitamin A has also been shown to be important for T cell homing

to the intestine, effects dendritic cells, and can play a role in

increased IgA secretion which is important for the immune response in mucosal tissues.

Dermatology

Vitamin

A, and more specifically, retinoic acid, appears to maintain normal

skin health by switching on genes and differentiating keratinocytes

(immature skin cells) into mature epidermal cells.

Exact mechanisms behind pharmacological retinoid therapy agents in the

treatment of dermatological diseases are being researched.

For the treatment of acne, the most prescribed retinoid drug is 13-cis retinoic acid (isotretinoin).

It reduces the size and secretion of the sebaceous glands. Although it

is known that 40 mg of isotretinoin will break down to an equivalent of

10 mg of ATRA — the mechanism of action of the drug (original brand name

Accutane) remains unknown and is a matter of some controversy.

Isotretinoin reduces bacterial numbers in both the ducts and skin

surface. This is thought to be a result of the reduction in sebum, a

nutrient source for the bacteria. Isotretinoin reduces inflammation via

inhibition of chemotactic responses of monocytes and neutrophils.

Isotretinoin also has been shown to initiate remodeling of the

sebaceous glands; triggering changes in gene expression that selectively

induce apoptosis. Isotretinoin is a teratogen with a number of potential side-effects. Consequently, its use requires medical supervision.

Retinal/retinol versus retinoic acid

Vitamin A deprived rats can be kept in good general health with supplementation of retinoic acid. This reverses the growth-stunting effects of vitamin A deficiency, as well as early stages of xerophthalmia.

However, such rats show infertility (in both male and females) and

continued degeneration of the retina, showing that these functions

require retinal or retinol, which are interconvertible but which cannot

be recovered from the oxidized retinoic acid. The requirement of retinol

to rescue reproduction in vitamin A deficient rats is now known to be

due to a requirement for local synthesis of retinoic acid from retinol

in testis and embryos.

Vitamin A and derivatives in medical use

Retinyl palmitate

has been used in skin creams, where it is broken down to retinol and

ostensibly metabolised to retinoic acid, which has potent biological

activity, as described above. The retinoids (for example, 13-cis-retinoic acid)

constitute a class of chemical compounds chemically related to retinoic

acid, and are used in medicine to modulate gene functions in place of

this compound. Like retinoic acid, the related compounds do not have

full vitamin A activity, but do have powerful effects on gene expression

and epithelial cell differentiation.

Pharmaceutics utilizing mega doses of naturally occurring retinoic acid

derivatives are currently in use for cancer, HIV, and dermatological

purposes. At high doses, side-effects are similar to vitamin A toxicity.

History

The discovery of vitamin A may have stemmed from research dating back to 1816, when physiologist François Magendie observed that dogs deprived of nutrition developed corneal ulcers and had a high mortality rate. In 1912, Frederick Gowland Hopkins demonstrated that unknown accessory factors found in milk, other than carbohydrates, proteins, and fats were necessary for growth in rats. Hopkins received a Nobel Prize for this discovery in 1929. By 1913, one of these substances was independently discovered by Elmer McCollum and Marguerite Davis at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, and Lafayette Mendel and Thomas Burr Osborne at Yale University

who studied the role of fats in the diet. McCollum and Davis ultimately

received credit because they submitted their paper three weeks before

Mendel and Osborne. Both papers appeared in the same issue of the Journal of Biological Chemistry in 1913. The "accessory factors" were termed "fat soluble" in 1918 and later "vitamin A" in 1920. In 1919, Harry Steenbock

(University of Wisconsin–Madison) proposed a relationship between

yellow plant pigments (beta-carotene) and vitamin A. In 1931, Swiss

chemist Paul Karrer described the chemical structure of vitamin A. Vitamin A was first synthesized in 1947 by two Dutch chemists, David Adriaan van Dorp and Jozef Ferdinand Arens.

During World War II, German bombers would attack at night to evade British defenses. In order to keep the 1939 invention of a new on-board Airborne Intercept Radar system secret from German bombers, the British Royal Ministry told newspapers that the nighttime defensive success of Royal Air Force pilots was due to a high dietary intake of carrots rich in vitamin A, propagating the myth that carrots enable people to see better in the dark.