A strip of eight PCR tubes, each containing a 100 μl reaction mixture

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a method widely used in molecular biology to make many copies of a specific DNA segment. Using PCR, a single copy (or more) of a DNA sequence is exponentially amplified

to generate thousands to millions of more copies of that particular DNA

segment. PCR is now a common and often indispensable technique used in medical laboratory and clinical laboratory research for a broad variety of applications including biomedical research and criminal forensics. PCR was developed by Kary Mullis in 1983 while he was an employee of the Cetus Corporation. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1993 (along with Michael Smith) for his work in developing the method.

The vast majority of PCR methods rely on thermal cycling.

Thermal cycling exposes reactants to repeated cycles of heating and

cooling to permit different temperature-dependent

reactions—specifically, DNA melting and enzyme-driven DNA replication. PCR employs two main reagents - primers (which are short single strand DNA fragments known as oligonucleotides that are a complementary sequence to the target DNA region) and a DNA polymerase.

In the first step of PCR, the two strands of the DNA double helix are

physically separated at a high temperature in a process called DNA melting.

In the second step, the temperature is lowered and the primers bind to

the complementary sequences of DNA. The two DNA strands then become templates for DNA polymerase to enzymatically assemble a new DNA strand from free nucleotides,

the building blocks of DNA. As PCR progresses, the DNA generated is

itself used as a template for replication, setting in motion a chain reaction in which the original DNA template is exponentially amplified.

Almost all PCR applications employ a heat-stable DNA polymerase, such as Taq polymerase, an enzyme originally isolated from the thermophilic bacterium Thermus aquaticus.

If the polymerase used was heat-susceptible, it would denature under

the high temperatures of the denaturation step. Before the use of Taq

polymerase, DNA polymerase had to be manually added every cycle, which

was a tedious and costly process.

Applications of the technique include DNA cloning for sequencing, gene cloning and manipulation, gene mutagenesis; construction of DNA-based phylogenies, or functional analysis of genes; diagnosis and monitoring of hereditary diseases; amplification of ancient DNA; analysis of genetic fingerprints for DNA profiling (for example, in forensic science and parentage testing); and detection of pathogens in nucleic acid tests for the diagnosis of infectious diseases.

Placing a strip of eight PCR tubes into a thermal cycler

Principles

A thermal cycler for PCR

An older model three-temperature thermal cycler for PCR

PCR amplifies a specific region of a DNA strand (the DNA target). Most PCR methods amplify DNA fragments of between 0.1 and 10 kilo base pairs (kbp) in length, although some techniques allow for amplification of fragments up to 40 kbp.

The amount of amplified product is determined by the available

substrates in the reaction, which become limiting as the reaction

progresses.

A basic PCR set-up requires several components and reagents, including a DNA template that contains the DNA target region to amplify; a DNA polymerase; an enzyme that polymerizes new DNA strands; heat-resistant Taq polymerase is especially common, as it is more likely to remain intact during the high-temperature DNA denaturation process; two DNA primers that are complementary to the 3' (three prime) ends of each of the sense and anti-sense

strands of the DNA target (DNA polymerase can only bind to and elongate

from a double-stranded region of DNA; without primers there is no

double-stranded initiation site at which the polymerase can bind);

specific primers that are complementary to the DNA target region are

selected beforehand, and are often custom-made in a laboratory or

purchased from commercial biochemical suppliers; deoxynucleoside triphosphates, or dNTPs (sometimes called "deoxynucleotide triphosphates"; nucleotides containing triphosphate groups), the building blocks from which the DNA polymerase synthesizes a new DNA strand; a buffer solution providing a suitable chemical environment for optimum activity and stability of the DNA polymerase; bivalent cations, typically magnesium (Mg) or manganese (Mn) ions; Mg2+ is the most common, but Mn2+ can be used for PCR-mediated DNA mutagenesis, as a higher Mn2+ concentration increases the error rate during DNA synthesis;

and monovalent cations, typically potassium (K) ions.

The reaction is commonly carried out in a volume of 10–200 μL in small reaction tubes (0.2–0.5 mL volumes) in a thermal cycler.

The thermal cycler heats and cools the reaction tubes to achieve the

temperatures required at each step of the reaction (see below). Many

modern thermal cyclers make use of the Peltier effect,

which permits both heating and cooling of the block holding the PCR

tubes simply by reversing the electric current. Thin-walled reaction

tubes permit favorable thermal conductivity to allow for rapid thermal

equilibration. Most thermal cyclers have heated lids to prevent

condensation at the top of the reaction tube. Older thermal cyclers

lacking a heated lid require a layer of oil on top of the reaction

mixture or a ball of wax inside the tube.

Procedure

Typically,

PCR consists of a series of 20–40 repeated temperature changes, called

thermal cycles, with each cycle commonly consisting of two or three

discrete temperature steps (see figure below). The cycling is often

preceded by a single temperature step at a very high temperature

(>90 °C (194 °F)), and followed by one hold at the end for final

product extension or brief storage. The temperatures used and the length

of time they are applied in each cycle depend on a variety of

parameters, including the enzyme used for DNA synthesis, the

concentration of bivalent ions and dNTPs in the reaction, and the melting temperature (Tm) of the primers. The individual steps common to most PCR methods are as follows:

- Initialization: This step is only required for DNA polymerases that require heat activation by hot-start PCR. It consists of heating the reaction chamber to a temperature of 94–96 °C (201–205 °F), or 98 °C (208 °F) if extremely thermostable polymerases are used, which is then held for 1–10 minutes.

- Denaturation: This step is the first regular cycling event and consists of heating the reaction chamber to 94–98 °C (201–208 °F) for 20–30 seconds. This causes DNA melting, or denaturation, of the double-stranded DNA template by breaking the hydrogen bonds between complementary bases, yielding two single-stranded DNA molecules.

- Annealing: In the next step, the reaction temperature is lowered to 50–65 °C (122–149 °F) for 20–40 seconds, allowing annealing of the primers to each of the single-stranded DNA templates. Two different primers are typically included in the reaction mixture: one for each of the two single-stranded complements containing the target region. The primers are single-stranded sequences themselves, but are much shorter than the length of the target region, complementing only very short sequences at the 3' end of each strand.

- It is critical to determine a proper temperature for the annealing step because efficiency and specificity are strongly affected by the annealing temperature. This temperature must be low enough to allow for hybridization of the primer to the strand, but high enough for the hybridization to be specific, i.e., the primer should bind only to a perfectly complementary part of the strand, and nowhere else. If the temperature is too low, the primer may bind imperfectly. If it is too high, the primer may not bind at all. A typical annealing temperature is about 3–5 °C below the Tm of the primers used. Stable hydrogen bonds between complementary bases are formed only when the primer sequence very closely matches the template sequence. During this step, the polymerase binds to the primer-template hybrid and begins DNA formation.

- Extension/elongation: The temperature at this step depends on the DNA polymerase used; the optimum activity temperature for the thermostable DNA polymerase of Taq (Thermus aquaticus) polymerase is approximately 75–80 °C (167–176 °F), though a temperature of 72 °C (162 °F) is commonly used with this enzyme. In this step, the DNA polymerase synthesizes a new DNA strand complementary to the DNA template strand by adding free dNTPs from the reaction mixture that are complementary to the template in the 5'-to-3' direction, condensing the 5'-phosphate group of the dNTPs with the 3'-hydroxy group at the end of the nascent (elongating) DNA strand. The precise time required for elongation depends both on the DNA polymerase used and on the length of the DNA target region to amplify. As a rule of thumb, at their optimal temperature, most DNA polymerases polymerize a thousand bases per minute. Under optimal conditions (i.e., if there are no limitations due to limiting substrates or reagents), at each extension/elongation step, the number of DNA target sequences is doubled. With each successive cycle, the original template strands plus all newly generated strands become template strands for the next round of elongation, leading to exponential (geometric) amplification of the specific DNA target region.

- The processes of denaturation, annealing and elongation constitute a single cycle. Multiple cycles are required to amplify the DNA target to millions of copies. The formula used to calculate the number of DNA copies formed after a given number of cycles is 2n, where n is the number of cycles. Thus, a reaction set for 30 cycles results in 230, or 1073741824, copies of the original double-stranded DNA target region.

- Final elongation: This single step is optional, but is performed at a temperature of 70–74 °C (158–165 °F) (the temperature range required for optimal activity of most polymerases used in PCR) for 5–15 minutes after the last PCR cycle to ensure that any remaining single-stranded DNA is fully elongated.

- Final hold: The final step cools the reaction chamber to 4–15 °C (39–59 °F) for an indefinite time, and may be employed for short-term storage of the PCR products.

Ethidium bromide-stained PCR products after gel electrophoresis.

Two sets of primers were used to amplify a target sequence from three

different tissue samples. No amplification is present in sample #1; DNA

bands in sample #2 and #3 indicate successful amplification of the

target sequence. The gel also shows a positive control, and a DNA ladder

containing DNA fragments of defined length for sizing the bands in the

experimental PCRs.

To check whether the PCR successfully generated the anticipated DNA

target region (also sometimes referred to as the amplimer or amplicon), agarose gel electrophoresis may be employed for size separation of the PCR products. The size(s) of PCR products is determined by comparison with a DNA ladder, a molecular weight marker which contains DNA fragments of known size run on the gel alongside the PCR products.

Stages

As with

other chemical reactions, the reaction rate and efficiency of PCR are

affected by limiting factors. Thus, the entire PCR process can further

be divided into three stages based on reaction progress:

- Exponential amplification: At every cycle, the amount of product is doubled (assuming 100% reaction efficiency). After 30 cycles, a single copy of DNA can be increased up to 1 000 000 000 (one billion) copies. In a sense, then, the replication of a discrete strand of DNA is being manipulated in a tube under controlled conditions. The reaction is very sensitive: only minute quantities of DNA must be present.

- Leveling off stage: The reaction slows as the DNA polymerase loses activity and as consumption of reagents such as dNTPs and primers causes them to become limiting.

- Plateau: No more product accumulates due to exhaustion of reagents and enzyme.

Optimization

In practice, PCR can fail for various reasons, in part due to its

sensitivity to contamination causing amplification of spurious DNA

products. Because of this, a number of techniques and procedures have

been developed for optimizing PCR conditions.

Contamination with extraneous DNA is addressed with lab protocols and

procedures that separate pre-PCR mixtures from potential DNA

contaminants.

This usually involves spatial separation of PCR-setup areas from areas

for analysis or purification of PCR products, use of disposable

plasticware, and thoroughly cleaning the work surface between reaction

setups. Primer-design techniques are important in improving PCR product

yield and in avoiding the formation of spurious products, and the usage

of alternate buffer components or polymerase enzymes can help with

amplification of long or otherwise problematic regions of DNA. Addition

of reagents, such as formamide, in buffer systems may increase the specificity and yield of PCR. Computer simulations of theoretical PCR results (Electronic PCR) may be performed to assist in primer design.

Applications

Selective DNA isolation

PCR

allows isolation of DNA fragments from genomic DNA by selective

amplification of a specific region of DNA. This use of PCR augments many

ways, such as generating hybridization probes for Southern or northern hybridization and DNA cloning,

which require larger amounts of DNA, representing a specific DNA

region. PCR supplies these techniques with high amounts of pure DNA,

enabling analysis of DNA samples even from very small amounts of

starting material.

Other applications of PCR include DNA sequencing to determine unknown PCR-amplified sequences in which one of the amplification primers may be used in Sanger sequencing, isolation of a DNA sequence to expedite recombinant DNA technologies involving the insertion of a DNA sequence into a plasmid, phage, or cosmid (depending on size) or the genetic material of another organism. Bacterial colonies (such as E. coli) can be rapidly screened by PCR for correct DNA vector constructs. PCR may also be used for genetic fingerprinting; a forensic technique used to identify a person or organism by comparing experimental DNAs through different PCR-based methods.

Some PCR 'fingerprints' methods have high discriminative power

and can be used to identify genetic relationships between individuals,

such as parent-child or between siblings, and are used in paternity

testing (Fig. 4). This technique may also be used to determine

evolutionary relationships among organisms when certain molecular clocks

are used (i.e., the 16S rRNA and recA genes of microorganisms).

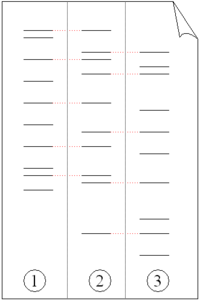

Electrophoresis

of PCR-amplified DNA fragments. (1) Father. (2) Child. (3) Mother. The

child has inherited some, but not all of the fingerprint of each of its

parents, giving it a new, unique fingerprint.

Amplification and quantification of DNA

Because PCR amplifies the regions of DNA that it targets, PCR can be

used to analyze extremely small amounts of sample. This is often

critical for forensic analysis, when only a trace amount of DNA is available as evidence. PCR may also be used in the analysis of ancient DNA

that is tens of thousands of years old. These PCR-based techniques have

been successfully used on animals, such as a forty-thousand-year-old mammoth, and also on human DNA, in applications ranging from the analysis of Egyptian mummies to the identification of a Russian tsar and the body of English king Richard III.

Quantitative PCR or Real Time PCR (qPCR, not to be confused with RT-PCR)

methods allow the estimation of the amount of a given sequence present

in a sample—a technique often applied to quantitatively determine levels

of gene expression.

Quantitative PCR is an established tool for DNA quantification that

measures the accumulation of DNA product after each round of PCR

amplification.

qPCR allows the quantification and detection of a specific DNA

sequence in real time since it measures concentration while the

synthesis process is taking place. There are two methods for

simultaneous detection and quantification. The first method consists of

using fluorescent

dyes that are retained nonspecifically in between the double strands.

The second method involves probes that code for specific sequences and

are fluorescently labeled. Detection of DNA using these methods can only

be seen after the hybridization of probes with its complementary DNA

takes place. An interesting technique combination is real-time PCR and

reverse transcription. This sophisticated technique, called RT-qPCR,

allows for the quantification of a small quantity of RNA. Through this

combined technique, mRNA is converted to cDNA, which is further

quantified using qPCR. This technique lowers the possibility of error at

the end point of PCR, increasing chances for detection of genes associated with genetic diseases such as cancer. Laboratories use RT-qPCR for the purpose of sensitively measuring gene regulation.

Medical and diagnostic applications

Prospective parents can be tested for being genetic carriers, or their children might be tested for actually being affected by a disease. DNA samples for prenatal testing can be obtained by amniocentesis, chorionic villus sampling, or even by the analysis of rare fetal cells circulating in the mother's bloodstream. PCR analysis is also essential to preimplantation genetic diagnosis, where individual cells of a developing embryo are tested for mutations.

- PCR can also be used as part of a sensitive test for tissue typing, vital to organ transplantation. As of 2008, there is even a proposal to replace the traditional antibody-based tests for blood type with PCR-based tests.

- Many forms of cancer involve alterations to oncogenes. By using PCR-based tests to study these mutations, therapy regimens can sometimes be individually customized to a patient. PCR permits early diagnosis of malignant diseases such as leukemia and lymphomas, which is currently the highest-developed in cancer research and is already being used routinely. PCR assays can be performed directly on genomic DNA samples to detect translocation-specific malignant cells at a sensitivity that is at least 10,000 fold higher than that of other methods. PCR is very useful in the medical field since it allows for the isolation and amplification of tumor suppressors. Quantitative PCR for example, can be used to quantify and analyze single cells, as well as recognize DNA, mRNA and protein confirmations and combinations.

Infectious disease applications

PCR allows for rapid and highly specific diagnosis of infectious diseases, including those caused by bacteria or viruses. PCR also permits identification of non-cultivatable or slow-growing microorganisms such as mycobacteria, anaerobic bacteria, or viruses from tissue culture assays and animal models.

The basis for PCR diagnostic applications in microbiology is the

detection of infectious agents and the discrimination of non-pathogenic

from pathogenic strains by virtue of specific genes.

Characterization and detection of infectious disease organisms have been revolutionized by PCR in the following ways:

- The human immunodeficiency virus (or HIV), is a difficult target to find and eradicate. The earliest tests for infection relied on the presence of antibodies to the virus circulating in the bloodstream. However, antibodies don't appear until many weeks after infection, maternal antibodies mask the infection of a newborn, and therapeutic agents to fight the infection don't affect the antibodies. PCR tests have been developed that can detect as little as one viral genome among the DNA of over 50,000 host cells. Infections can be detected earlier, donated blood can be screened directly for the virus, newborns can be immediately tested for infection, and the effects of antiviral treatments can be quantified.

- Some disease organisms, such as that for tuberculosis, are difficult to sample from patients and slow to be grown in the laboratory. PCR-based tests have allowed detection of small numbers of disease organisms (both live or dead), in convenient samples. Detailed genetic analysis can also be used to detect antibiotic resistance, allowing immediate and effective therapy. The effects of therapy can also be immediately evaluated.

- The spread of a disease organism through populations of domestic or wild animals can be monitored by PCR testing. In many cases, the appearance of new virulent sub-types can be detected and monitored. The sub-types of an organism that were responsible for earlier epidemics can also be determined by PCR analysis.

- Viral DNA can be detected by PCR. The primers used must be specific to the targeted sequences in the DNA of a virus, and PCR can be used for diagnostic analyses or DNA sequencing of the viral genome. The high sensitivity of PCR permits virus detection soon after infection and even before the onset of disease. Such early detection may give physicians a significant lead time in treatment. The amount of virus ("viral load") in a patient can also be quantified by PCR-based DNA quantitation techniques (see below).

- Diseases such as pertussis (or whooping cough) are cause by the bacteria Bordetella pertussis. This bacteria is marked by a serious acute respiratory infection that affects various animals and humans and has led to the deaths of many young children. The pertussis toxin is a protein exotoxin that binds to cell receptors by two dimers and reacts with different cell types such as T lymphocytes which plays a role in cell immunity. PCR is an important testing tool that can detect the sequences that are within the pertussis toxin gene. This is because PCR has a high sensitivity for the toxin and has demonstrated a rapid turnaround time. PCR is very efficient for diagnosing pertussis when compared to culture.

Forensic applications

The development of PCR-based genetic (or DNA) fingerprinting protocols has seen widespread application in forensics:

- In its most discriminating form, genetic fingerprinting can uniquely discriminate any one person from the entire population of the world. Minute samples of DNA can be isolated from a crime scene, and compared to that from suspects, or from a DNA database of earlier evidence or convicts. Simpler versions of these tests are often used to rapidly rule out suspects during a criminal investigation. Evidence from decades-old crimes can be tested, confirming or exonerating the people originally convicted.

- Forensic DNA typing has been an effective way of identifying or exonerating criminal suspects due to analysis of evidence discovered at a crime scene. The human genome has many repetitive regions that can be found within gene sequences or in non-coding regions of the genome. Specifically, up to 40% of human DNA is repetitive. There are two distinct categories for these repetitive, non-coding regions in the genome. The first category is called variable number tandem repeats (VNTR), which are 10-100 base pairs long and the second category is called short tandem repeats (STR) and these consist of repeated 2-10 base pair sections. PCR is used to amplify several well-known VNTRs and STRs using primers that flank each of the repetitive regions. The sizes of the fragments obtained from any individual for each of the STRs will indicate which alleles are present. By analyzing several STRs for an individual, a set of alleles for each person will be found that statistically is likely to be unique. Researchers have identified the complete sequence of the human genome. This sequence can be easily accessed through the NCBI website and is used in many real-life applications. For example, the FBI has compiled a set of DNA marker sites used for identification, and these are called the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS) DNA database. Using this database enables statistical analysis to be used to determine the probability that a DNA sample will match. PCR is a very powerful and significant analytical tool to use for forensic DNA typing because researchers only need a very small amount of the target DNA to be used for analysis. For example, a single human hair with attached hair follicle has enough DNA to conduct the analysis. Similarly, a few sperm, skin samples from under the fingernails, or a small amount of blood can provide enough DNA for conclusive analysis.

- Less discriminating forms of DNA fingerprinting can help in DNA paternity testing, where an individual is matched with their close relatives. DNA from unidentified human remains can be tested, and compared with that from possible parents, siblings, or children. Similar testing can be used to confirm the biological parents of an adopted (or kidnapped) child. The actual biological father of a newborn can also be confirmed (or ruled out).

- The PCR AMGX/AMGY design has been shown to not only facilitating in amplifying DNA sequences from a very minuscule amount of genome. However it can also be used for real time sex determination from forensic bone samples. This provides us with a powerful and effective way to determine the sex of not only ancient specimens but also current suspects in crimes.

Research applications

PCR has been applied to many areas of research in molecular genetics:

- PCR allows rapid production of short pieces of DNA, even when not more than the sequence of the two primers is known. This ability of PCR augments many methods, such as generating hybridization probes for Southern or northern blot hybridization. PCR supplies these techniques with large amounts of pure DNA, sometimes as a single strand, enabling analysis even from very small amounts of starting material.

- The task of DNA sequencing can also be assisted by PCR. Known segments of DNA can easily be produced from a patient with a genetic disease mutation. Modifications to the amplification technique can extract segments from a completely unknown genome, or can generate just a single strand of an area of interest.

- PCR has numerous applications to the more traditional process of DNA cloning. It can extract segments for insertion into a vector from a larger genome, which may be only available in small quantities. Using a single set of 'vector primers', it can also analyze or extract fragments that have already been inserted into vectors. Some alterations to the PCR protocol can generate mutations (general or site-directed) of an inserted fragment.

- Sequence-tagged sites is a process where PCR is used as an indicator that a particular segment of a genome is present in a particular clone. The Human Genome Project found this application vital to mapping the cosmid clones they were sequencing, and to coordinating the results from different laboratories.

- An exciting application of PCR is the phylogenic analysis of DNA from ancient sources, such as that found in the recovered bones of Neanderthals, from frozen tissues of mammoths, or from the brain of Egyptian mummies. Have been amplified and sequenced. In some cases the highly degraded DNA from these sources might be reassembled during the early stages of amplification.

- A common application of PCR is the study of patterns of gene expression. Tissues (or even individual cells) can be analyzed at different stages to see which genes have become active, or which have been switched off. This application can also use quantitative PCR to quantitate the actual levels of expression.

- The ability of PCR to simultaneously amplify several loci from individual sperm has greatly enhanced the more traditional task of genetic mapping by studying chromosomal crossovers after meiosis. Rare crossover events between very close loci have been directly observed by analyzing thousands of individual sperms. Similarly, unusual deletions, insertions, translocations, or inversions can be analyzed, all without having to wait (or pay) for the long and laborious processes of fertilization, embryogenesis, etc.

- Site-directed mutagenesis: PCR can be used to create mutant genes with mutations chosen by scientists at will. These mutations can be chosen in order to understand how proteins accomplish their functions, and to change or improve protein function.

Advantages

PCR

has a number of advantages. It is fairly simple to understand and to

use, and produces results rapidly. The technique is highly sensitive

with the potential to produce millions to billions of copies of a

specific product for sequencing, cloning, and analysis. qRT-PCR shares

the same advantages as the PCR, with an added advantage of

quantification of the synthesized product. Therefore, it has its uses to

analyze alterations of gene expression levels in tumors, microbes, or

other disease states.

PCR is a very powerful and practical research tool. The

sequencing of unknown etiologies of many diseases are being figured out

by the PCR. The technique can help identify the sequence of previously

unknown viruses related to those already known and thus give us a better

understanding of the disease itself. If the procedure can be further

simplified and sensitive non radiometric detection systems can be

developed, the PCR will assume a prominent place in the clinical

laboratory for years to come.

Limitations

One

major limitation of PCR is that prior information about the target

sequence is necessary in order to generate the primers that will allow

its selective amplification.

This means that, typically, PCR users must know the precise sequence(s)

upstream of the target region on each of the two single-stranded

templates in order to ensure that the DNA polymerase properly binds to

the primer-template hybrids and subsequently generates the entire target

region during DNA synthesis.

Like all enzymes, DNA polymerases are also prone to error, which

in turn causes mutations in the PCR fragments that are generated.

Another limitation of PCR is that even the smallest amount of

contaminating DNA can be amplified, resulting in misleading or ambiguous

results. To minimize the chance of contamination, investigators should

reserve separate rooms for reagent preparation, the PCR, and analysis of

product. Reagents should be dispensed into single-use aliquots. Pipetters with disposable plungers and extra-long pipette tips should be routinely used.

Variations

- Allele-specific PCR: a diagnostic or cloning technique based on single-nucleotide variations (SNVs not to be confused with SNPs) (single-base differences in a patient). It requires prior knowledge of a DNA sequence, including differences between alleles, and uses primers whose 3' ends encompass the SNV (base pair buffer around SNV usually incorporated). PCR amplification under stringent conditions is much less efficient in the presence of a mismatch between template and primer, so successful amplification with an SNP-specific primer signals presence of the specific SNP in a sequence.

- Assembly PCR or Polymerase Cycling Assembly (PCA): artificial synthesis of long DNA sequences by performing PCR on a pool of long oligonucleotides with short overlapping segments. The oligonucleotides alternate between sense and antisense directions, and the overlapping segments determine the order of the PCR fragments, thereby selectively producing the final long DNA product.

- Asymmetric PCR: preferentially amplifies one DNA strand in a double-stranded DNA template. It is used in sequencing and hybridization probing where amplification of only one of the two complementary strands is required. PCR is carried out as usual, but with a great excess of the primer for the strand targeted for amplification. Because of the slow (arithmetic) amplification later in the reaction after the limiting primer has been used up, extra cycles of PCR are required. A recent modification on this process, known as Linear-After-The-Exponential-PCR (LATE-PCR), uses a limiting primer with a higher melting temperature (Tm) than the excess primer to maintain reaction efficiency as the limiting primer concentration decreases mid-reaction.

- Convective PCR: a pseudo-isothermal way of performing PCR. Instead of repeatedly heating and cooling the PCR mixture, the solution is subjected to a thermal gradient. The resulting thermal instability driven convective flow automatically shuffles the PCR reagents from the hot and cold regions repeatedly enabling PCR. Parameters such as thermal boundary conditions and geometry of the PCR enclosure can be optimized to yield robust and rapid PCR by harnessing the emergence of chaotic flow fields. Such convective flow PCR setup significantly reduces device power requirement and operation time.

- Dial-out PCR: a highly parallel method for retrieving accurate DNA molecules for gene synthesis. A complex library of DNA molecules is modified with unique flanking tags before massively parallel sequencing. Tag-directed primers then enable the retrieval of molecules with desired sequences by PCR.

- Digital PCR (dPCR): used to measure the quantity of a target DNA sequence in a DNA sample. The DNA sample is highly diluted so that after running many PCRs in parallel, some of them do not receive a single molecule of the target DNA. The target DNA concentration is calculated using the proportion of negative outcomes. Hence the name 'digital PCR'.

- Helicase-dependent amplification: similar to traditional PCR, but uses a constant temperature rather than cycling through denaturation and annealing/extension cycles. DNA helicase, an enzyme that unwinds DNA, is used in place of thermal denaturation.

- Hot start PCR: a technique that reduces non-specific amplification during the initial set up stages of the PCR. It may be performed manually by heating the reaction components to the denaturation temperature (e.g., 95 °C) before adding the polymerase. Specialized enzyme systems have been developed that inhibit the polymerase's activity at ambient temperature, either by the binding of an antibody or by the presence of covalently bound inhibitors that dissociate only after a high-temperature activation step. Hot-start/cold-finish PCR is achieved with new hybrid polymerases that are inactive at ambient temperature and are instantly activated at elongation temperature.

- In silico PCR (digital PCR, virtual PCR, electronic PCR, e-PCR) refers to computational tools used to calculate theoretical polymerase chain reaction results using a given set of primers (probes) to amplify DNA sequences from a sequenced genome or transcriptome. In silico PCR was proposed as an educational tool for molecular biology.

- Intersequence-specific PCR (ISSR): a PCR method for DNA fingerprinting that amplifies regions between simple sequence repeats to produce a unique fingerprint of amplified fragment lengths.

- Inverse PCR: is commonly used to identify the flanking sequences around genomic inserts. It involves a series of DNA digestions and self ligation, resulting in known sequences at either end of the unknown sequence.

- Ligation-mediated PCR: uses small DNA linkers ligated to the DNA of interest and multiple primers annealing to the DNA linkers; it has been used for DNA sequencing, genome walking, and DNA footprinting.

- Methylation-specific PCR (MSP): developed by Stephen Baylin and James G. Herman at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, and is used to detect methylation of CpG islands in genomic DNA. DNA is first treated with sodium bisulfite, which converts unmethylated cytosine bases to uracil, which is recognized by PCR primers as thymine. Two PCRs are then carried out on the modified DNA, using primer sets identical except at any CpG islands within the primer sequences. At these points, one primer set recognizes DNA with cytosines to amplify methylated DNA, and one set recognizes DNA with uracil or thymine to amplify unmethylated DNA. MSP using qPCR can also be performed to obtain quantitative rather than qualitative information about methylation.

- Miniprimer PCR: uses a thermostable polymerase (S-Tbr) that can extend from short primers ("smalligos") as short as 9 or 10 nucleotides. This method permits PCR targeting to smaller primer binding regions, and is used to amplify conserved DNA sequences, such as the 16S (or eukaryotic 18S) rRNA gene.

- Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA): permits amplifying multiple targets with a single primer pair, thus avoiding the resolution limitations of multiplex PCR.

- Multiplex-PCR: consists of multiple primer sets within a single PCR mixture to produce amplicons of varying sizes that are specific to different DNA sequences. By targeting multiple genes at once, additional information may be gained from a single test-run that otherwise would require several times the reagents and more time to perform. Annealing temperatures for each of the primer sets must be optimized to work correctly within a single reaction, and amplicon sizes. That is, their base pair length should be different enough to form distinct bands when visualized by gel electrophoresis.

- Nanoparticle-Assisted PCR (nanoPCR): In recent years, it has been reported that some nanoparticles (NPs) can enhance the efficiency of PCR (thus being called nanoPCR), and some even perform better than the original PCR enhancers. It was also found that quantum dots (QDs) can improve PCR specificity and efficiency. Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) and multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) are efficient in enhancing the amplification of long PCR. Carbon nanopowder (CNP) was reported be able to improve the efficiency of repeated PCR and long PCR. ZnO, TiO2, and Ag NPs were also found to increase PCR yield. Importantly, already known data has indicated that non-metallic NPs retained acceptable amplification fidelity. Given that many NPs are capable of enhancing PCR efficiency, it is clear that there is likely to be great potential for nanoPCR technology improvements and product development.

- Nested PCR: increases the specificity of DNA amplification, by reducing background due to non-specific amplification of DNA. Two sets of primers are used in two successive PCRs. In the first reaction, one pair of primers is used to generate DNA products, which besides the intended target, may still consist of non-specifically amplified DNA fragments. The product(s) are then used in a second PCR with a set of primers whose binding sites are completely or partially different from and located 3' of each of the primers used in the first reaction. Nested PCR is often more successful in specifically amplifying long DNA fragments than conventional PCR, but it requires more detailed knowledge of the target sequences.

- Overlap-extension PCR or Splicing by overlap extension (SOEing) : a genetic engineering technique that is used to splice together two or more DNA fragments that contain complementary sequences. It is used to join DNA pieces containing genes, regulatory sequences, or mutations; the technique enables creation of specific and long DNA constructs. It can also introduce deletions, insertions or point mutations into a DNA sequence.

- PAN-AC: uses isothermal conditions for amplification, and may be used in living cells.

- quantitative PCR (qPCR): used to measure the quantity of a target sequence (commonly in real-time). It quantitatively measures starting amounts of DNA, cDNA, or RNA. quantitative PCR is commonly used to determine whether a DNA sequence is present in a sample and the number of its copies in the sample. Quantitative PCR has a very high degree of precision. Quantitative PCR methods use fluorescent dyes, such as Sybr Green, EvaGreen or fluorophore-containing DNA probes, such as TaqMan, to measure the amount of amplified product in real time. It is also sometimes abbreviated to RT-PCR (real-time PCR) but this abbreviation should be used only for reverse transcription PCR. qPCR is the appropriate contractions for quantitative PCR (real-time PCR).

- Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-PCR): for amplifying DNA from RNA. Reverse transcriptase reverse transcribes RNA into cDNA, which is then amplified by PCR. RT-PCR is widely used in expression profiling, to determine the expression of a gene or to identify the sequence of an RNA transcript, including transcription start and termination sites. If the genomic DNA sequence of a gene is known, RT-PCR can be used to map the location of exons and introns in the gene. The 5' end of a gene (corresponding to the transcription start site) is typically identified by RACE-PCR (Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends).

- RNase H-dependent PCR (rhPCR): a modification of PCR that utilizes primers with a 3’ extension block that can be removed by a thermostable RNase HII enzyme. This system reduces primer-dimers and allows for multiplexed reactions to be performed with higher numbers of primers.

- Single Specific Primer-PCR (SSP-PCR): allows the amplification of double-stranded DNA even when the sequence information is available at one end only. This method permits amplification of genes for which only a partial sequence information is available, and allows unidirectional genome walking from known into unknown regions of the chromosome.

- Solid Phase PCR: encompasses multiple meanings, including Polony Amplification (where PCR colonies are derived in a gel matrix, for example), Bridge PCR (primers are covalently linked to a solid-support surface), conventional Solid Phase PCR (where Asymmetric PCR is applied in the presence of solid support bearing primer with sequence matching one of the aqueous primers) and Enhanced Solid Phase PCR (where conventional Solid Phase PCR can be improved by employing high Tm and nested solid support primer with optional application of a thermal 'step' to favour solid support priming).

- Suicide PCR: typically used in paleogenetics or other studies where avoiding false positives and ensuring the specificity of the amplified fragment is the highest priority. It was originally described in a study to verify the presence of the microbe Yersinia pestis in dental samples obtained from 14th Century graves of people supposedly killed by plague during the medieval Black Death epidemic. The method prescribes the use of any primer combination only once in a PCR (hence the term "suicide"), which should never have been used in any positive control PCR reaction, and the primers should always target a genomic region never amplified before in the lab using this or any other set of primers. This ensures that no contaminating DNA from previous PCR reactions is present in the lab, which could otherwise generate false positives.

- Thermal asymmetric interlaced PCR (TAIL-PCR): for isolation of an unknown sequence flanking a known sequence. Within the known sequence, TAIL-PCR uses a nested pair of primers with differing annealing temperatures; a degenerate primer is used to amplify in the other direction from the unknown sequence.

- Touchdown PCR (Step-down PCR): a variant of PCR that aims to reduce nonspecific background by gradually lowering the annealing temperature as PCR cycling progresses. The annealing temperature at the initial cycles is usually a few degrees (3–5 °C) above the Tm of the primers used, while at the later cycles, it is a few degrees (3–5 °C) below the primer Tm. The higher temperatures give greater specificity for primer binding, and the lower temperatures permit more efficient amplification from the specific products formed during the initial cycles.

- Universal Fast Walking: for genome walking and genetic fingerprinting using a more specific 'two-sided' PCR than conventional 'one-sided' approaches (using only one gene-specific primer and one general primer—which can lead to artefactual 'noise') by virtue of a mechanism involving lariat structure formation. Streamlined derivatives of UFW are LaNe RAGE (lariat-dependent nested PCR for rapid amplification of genomic DNA ends), 5'RACE LaNe and 3'RACE LaNe.

History

Diagrammatic

representation of an example primer pair. The use of primers in an in

vitro assay to allow DNA synthesis was a major innovation that allowed

the development of PCR.

A 1971 paper in the Journal of Molecular Biology by Kjell Kleppe and co-workers in the laboratory of H. Gobind Khorana first described a method of using an enzymatic assay to replicate a short DNA template with primers in vitro.

However, this early manifestation of the basic PCR principle did not

receive much attention at the time and the invention of the polymerase

chain reaction in 1983 is generally credited to Kary Mullis.

"Baby Blue", a 1986 prototype machine for doing PCR

When Mullis developed the PCR in 1983, he was working in Emeryville, California for Cetus Corporation, one of the first biotechnology

companies, where he was responsible for synthesizing short chains of

DNA. Mullis has written that he first conceived the idea for PCR while

cruising along the Pacific Coast Highway one night in his car.

He was playing in his mind with a new way of analyzing changes

(mutations) in DNA when he realized that he had instead invented a

method of amplifying any DNA region through repeated cycles of

duplication driven by DNA polymerase. In Scientific American,

Mullis summarized the procedure: "Beginning with a single molecule of

the genetic material DNA, the PCR can generate 100 billion similar

molecules in an afternoon. The reaction is easy to execute. It requires

no more than a test tube, a few simple reagents, and a source of heat." DNA fingerprinting was first used for paternity testing in 1988.

Mullis was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1993 for his invention, seven years after he and his colleagues at Cetus first put his proposal to practice.

Mullis’s 1985 paper with R. K. Saiki and H. A. Erlich, “Enzymatic

Amplification of β-globin Genomic Sequences and Restriction Site

Analysis for Diagnosis of Sickle Cell Anemia”—the polymerase chain

reaction invention (PCR) -- was honored by a Citation for Chemical

Breakthrough Award from the Division of History of Chemistry of the

American Chemical Society in 2017.

Some controversies have remained about the intellectual and

practical contributions of other scientists to Mullis' work, and whether

he had been the sole inventor of the PCR principle

At the core of the PCR method is the use of a suitable DNA polymerase able to withstand the high temperatures of more than 90 °C (194 °F) required for separation of the two DNA strands in the DNA double helix after each replication cycle. The DNA polymerases initially employed for in vitro experiments presaging PCR were unable to withstand these high temperatures.

So the early procedures for DNA replication were very inefficient and

time-consuming, and required large amounts of DNA polymerase and

continuous handling throughout the process.

The discovery in 1976 of Taq polymerase—a DNA polymerase purified from the thermophilic bacterium, Thermus aquaticus, which naturally lives in hot (50 to 80 °C (122 to 176 °F)) environments such as hot springs—paved the way for dramatic improvements of the PCR method. The DNA polymerase isolated from T. aquaticus is stable at high temperatures remaining active even after DNA denaturation, thus obviating the need to add new DNA polymerase after each cycle. This allowed an automated thermocycler-based process for DNA amplification.

Patent disputes

The PCR technique was patented by Kary Mullis and assigned to Cetus Corporation, where Mullis worked when he invented the technique in 1983. The Taq

polymerase enzyme was also covered by patents. There have been several

high-profile lawsuits related to the technique, including an

unsuccessful lawsuit brought by DuPont. The pharmaceutical company Hoffmann-La Roche purchased the rights to the patents in 1992 and currently holds those that are still protected.

A related patent battle over the Taq polymerase enzyme is still

ongoing in several jurisdictions around the world between Roche and Promega.

The legal arguments have extended beyond the lives of the original PCR

and Taq polymerase patents, which expired on March 28, 2005.