In Judaism, slaves were given a range of treatments and protections. They were to be treated as extended family with certain protections and could be freed. They were property but could also own material goods.

Early Christian authors maintained spiritual equality of slaves and free persons, while accepting slavery as an institution. Early modern papal decrees allowed enslavement of unbelievers, though some popes denounced slavery from the 15th century onwards. In the eighteenth century the abolition movement took shape among Christians across the globe, but various denominations continued to be pro-slavery into the 19th century. Enslaved non-believers were sometimes converted to Christianity, but elements of their traditional beliefs merged with their Christian beliefs.

Early Islamic texts encourage kindness towards slaves and manumission, while permitting enslavement of non-Muslim prisoners of war.

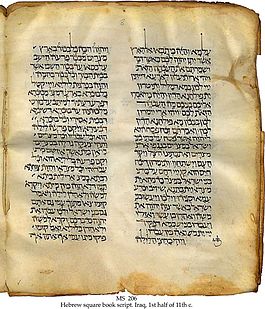

Slavery in the Bible

Genesis narrative about the Curse of Ham has often been held to be an aetiological story, giving a reason for the enslavement of the Canaanites. The word ham is very similar to the Hebrew word for hot, which is cognate with an Egyptian word (kem, meaning black) used to refer to Egypt itself, in reference to the fertile black soil along the Nile valley. Although many scholars therefore view Ham as an eponym used to represent Egypt in the Table of Nations, a number of Christians throughout history, including Origen and the Cave of Treasures, have argued for the alternate proposition that Ham represents all black people, his name symbolising their dark skin colour; pro-slavery advocates, from Eutychius of Alexandria and John Philoponus, to American pro-slavery apologists, have therefore occasionally interpreted the narrative as a condemnation of all black people to slavery. A few Christians, like Jerome, even took up the racist notion that black people inherently had a soul as black as [their] body.

Slavery was customary in antiquity, and it is condoned by the Torah. The Bible uses the Hebrew term ebed to refer to slavery; however, ebed has a much wider meaning than the English term slavery, and in several circumstances it is more accurately translated into English as servant. It was seen as legitimate to enslave captives obtained through warfare, but not through kidnapping. Children could also be sold into debt bondage, which was sometimes ordered by a court of law.

As with the Hittite Laws and the Code of Hammurabi,

the Bible does set minimum rules for the conditions under which slaves

were to be kept. Slaves were to be treated as part of an extended

family; they were allowed to celebrate the Sukkot festival, and expected to honour Shabbat. Israelite slaves could not be compelled to work with rigour, and debtors who sold themselves as slaves to their creditors had to be treated the same as a hired servant. If a master harmed a slave in one of the ways covered by the lex talionis, the slave was to be compensated by manumission; if the slave died within 24 to 48 hours, he or she was to be avenged (whether this refers to the death penalty or not is uncertain).

Israelite slaves were automatically manumitted after six years of work, and/or at the next Jubilee

(occurring either every 49 or every 50 years, depending on

interpretation), although the latter would not apply if the slave was

owned by an Israelite and wasn't in debt bondage. Slaves released automatically in their 7th year of service, which did not include female slaves, or did, were to be given livestock, grain, and wine, as a parting gift (possibly hung round their necks). This 7th-year manumission could be voluntarily renounced, which would be signified, as in other Ancient Near Eastern nations, by the slave gaining a ritual ear piercing; after such renunciation, the individual was enslaved forever (and not released at the Jubilee). Non-Israelite slaves were always to be enslaved forever, and treated as inheritable property.

In several Pauline epistles, and the First Epistle of Peter, slaves are admonished to obey their masters, as to the Lord, and not to men; however these particular Pauline epistles are also those whose Pauline authorship is doubted by many modern scholars. By contrast, the First Epistle to the Corinthians, one of the undisputed epistles, describes lawfully obtained manumission as the ideal for slaves. Another undisputed epistle is that to Philemon, which has become an important text in regard to slavery, being used by pro-slavery advocates as well as by abolitionists; in the epistle, Paul returns Onesimus, a fugitive slave, back to his master.

Judaism

More mainstream forms of first-century Judaism

did not exhibit such qualms about slavery, and ever since the

2nd-century expulsion of Jews from Judea, wealthy Jews have owned

non-Jewish slaves, wherever it was legal to do so;

nevertheless, manumissions were approved by Jewish religious officials

on the slightest of pretexts, and court cases concerning manumission

were nearly always decided in favour of freedom, whenever there was

uncertainty towards the facts.

The Talmud,

a document of great importance in Judaism, made many rulings which had

the effect of making manumission easier and more likely:

- The costly and compulsory giving of gifts was restricted the 7th-year manumission only.

- The price of freedom was reduced to a proportion of the original purchase price rather than the total fee of a hired servant, and could be reduced further if the slave had become weak or sickly (and therefore less saleable).

- Voluntary manumission became officially possible, with the introduction of the manumission deed (the shetar shihrur), which was counted as prima facie proof of manumission.

- Verbal declarations of manumission could no longer be revoked.

- Putting phylacteries on the slave, or making him publicly read three or more verses from the Torah, was counted as a declaration of the slave's manumission.

- Extremely long term sickness, for up to four years in total, couldn't count against the slave's right to manumission after six years of enslavement.

Jewish participation in the slave trade itself was also regulated by the Talmud. Fear of apostasy lead to the Talmudic discouragement of the sale of Jewish slaves to non-Jews, although loans were allowed; similarly slave trade with Tyre was only to be for the purpose of removing slaves from non-Jewish religion. Religious racism meant that the Talmudic writers completely forbade the sale or transfer of Canaanite slaves out from Palestine to elsewhere. Other types of trade were also discouraged: men selling themselves to women, and post-pubescent daughters being sold into slavery by their fathers. Pre-pubescent slave girls sold by their fathers had to be freed-then-married by their new owner, or his son, when she started puberty; slaves could not be allowed to marry free Jews, although masters were often granted access to the services of the wives of any of their slaves.

According to the Talmudic law, killing of a slave is punishable

in the same way as killing of a freeman, even if it was committed by the

owner. While slaves are considered the owner's property, they may not

work on Sabbath and holidays; they may acquire and hold property of the

own.

Several prominent Jewish writers of the Middle Ages took offense at the idea that Jews might be enslaved; Joseph Caro and Maimonides both argue that calling a Jew slave was so offensive that it should be punished by excommunication.

However, they did not condemn enslavement of non-Jews. Indeed, they

argued that the biblical rule, that slaves should be freed for certain

injuries, should actually only apply to slaves who had converted to

Judaism;

additionally, Maimonides argued that this manumission was really

punishment of the owner, and therefore it could only be imposed by a

court, and required evidence from witnesses.

Unlike the biblical law protecting fugitive slaves, Maimonides argued

that such slaves should be compelled to buy their freedom.

At the same time, Maimonides and other halachic

authorities forbade or strongly discouraged any unethical treatment of

slaves. According to the traditional Jewish law, a slave is more like an

indentured servant, who has rights and should be treated almost like a

member of the owner's family. Maimonides wrote that, regardless whether a

slave is Jewish or not, "The way of the pious and the wise is to be

compassionate and to pursue justice, not to overburden or oppress a

slave, and to provide them from every dish and every drink. The early

sages would give their slaves from every dish on their table. They would

feed their servants before sitting to their own meals... Slaves may not

be maltreated of offended - the law destined them for service, not for

humiliation. Do not shout at them or be angry with them, but hear them

out." In another context, Maimonides wrote that all the laws of slavery

are "mercy, compassion and forbearance".

Christianity

Slavery in different forms existed within Christianity for over 18 centuries. Although in the early years of Christianity, freeing slaves was regarded as an act of charity, and the Christian view of equality of all people including slaves was a novelty in the Roman Empire, the institution of slavery was rarely criticised. David Brion Davis

writes that the "variations in early Christian opinion on servitude fit

comfortably within a framework of thought that would exclude any

attempt to abolish slavery as an institution". Indeed, in 340, the Synod of Gangra condemned the Manicheans

for their urging that slaves should liberate themselves; the canons of

the Synod instead declared that anyone preaching abolitionism should be

anathematised, and that slaves had a "Christian obligation" to submit to

their masters. Augustine of Hippo, who renounced his former Manicheanism, argued that slavery was part of the mechanism to preserve the natural order of things; John Chrysostom, regarded as a saint by Eastern Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism, argued that slaves should be resigned to their fate, as by "obeying his master he is obeying God". but also stated that "Slavery is the fruit of covetousness, of extravagance, of insatiable greediness" in his Epist. ad Ephes.

As the Apostle Paul admonished the early Christians; "There is neither

Jew nor Greek: there is neither bond nor free: there is neither male nor

female. For you are all one in Christ Jesus". And in fact, even some of

the first popes were once slaves themselves.

In 1452 Pope Nicholas V issued the papal bull Dum Diversas,

which granted Afonso V of Portugal the right to reduce any "Saracens,

pagans and any other unbelievers" to hereditary slavery. The approval of

slavery under these conditions was reaffirmed and extended in his

Romanus Pontifex bull of 1455. (This was regarding wars caused by the

fall on constantinople) In 1488 Pope Innocent VIII accepted the gift of 100 slaves from Ferdinand II of Aragon and distributed those slaves to his cardinals and the Roman nobility. Also, in 1639 Pope Urban VIII purchased slaves for himself from the Knights of Malta.

Other Popes in the 15th and 16th century denounced slavery as a great crime, including Pius II, Paul III, and Eugene IV.

In 1639, pope Urban VIII forbade slavery, as did Benedict XIV in 1741.

In 1815, pope Pius VII demanded of the Congress of Vienna the

suppression of the slave trade, and Gregory XVI condemned it again in

1839.

In addition, the Dominican friars who arrived at the Spanish

settlement at Santo Domingo in 1510 strongly denounced the enslavement

of the local Indians. Along with other priests, they opposed their

treatment as unjust and illegal in an audience with the Spanish king and

in the subsequent royal commission. As a response to this position, the Spanish monarchy's subsequent Requerimiento

provided a religious justification for the enslavement of the local

populations, on the pretext of refusing conversion to Roman Catholicism

and therefore denying the authority of the Pope.

Some other Christian organizations were slaveholders. The 18th-century high-church Anglican Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts owned the Codrington Plantation, in Barbados, containing several hundred slaves, branded on their chests with the word Society. George Whitefield, famed for his sparking of the so-called Great Awakening of American evangelicalism, overturned a province-wide ban against slavery, and went on to own several hundred slaves himself. Yet Whitefield is remembered as one of the first to preach to the enslaved.

At other times, Christian groups worked against slavery. The 7th-century Saint Eloi used his vast wealth to purchase British and Saxon slaves in groups of 50 and 100 in order to set them free. The Quakers in particular were early leaders in abolitionism, attacking slavery since at least 1688. In 1787 the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade was formed, with 9 of the 12 founder members being Quakers; William Wilberforce, an early supporter of the society, went on to push through the 1807 Slave Trade Act, striking a major blow against the transatlantic slave trade. Leaders of Methodism and Presbyterianism also vehemently denounced human bondage, convincing their congregations to do likewise; Methodists and Presbyterians subsequently made the repudiation of slavery a condition of membership.

In the Southern United States, however, support for slavery was strong; anti-slavery literature was prevented from passing through the postal system, and even sermons, from the famed English preacher Charles Spurgeon, were burned due to their censure of slavery. When the American Civil War broke out, slavery became one of the issues which would be decided by its outcome; the southern defeat led to a constitutional ban on slavery. Despite the general emancipation of slaves, members of fringe white Protestant groups like the Christian Identity movement, and the Ku Klux Klan (a white supremacist group) see the enslavement of Africans as a positive aspect of American history.

Slave Christianity

In the United States,

Christianity not only held views about slavery but also on how slaves

practiced their own form of Christianity. Prior to the work of Melville Herskovits

in 1941, it was widely believed that all elements of African culture

were destroyed by the horrific experiences of Africans forced to come to

the United States of America. Since his groundbreaking work,

scholarship has found that Slave Christianity existed as an

extraordinarily creative patchwork of African and Christian religious

tradition. The slaves brought with them a wide variety of religious traditions including both tribal shamanism and Islam. Beyond that, tribal traditions could vary to a high degree across the African continent.

During the early eighteenth century, Anglican missionaries

attempting to bring Christianity to slaves in the Southern colonies

often found themselves butting up against not only uncooperative

masters, but also resistant slaves. An unquestionable obstacle to the

acceptance of Christianity among slaves was their desire to continue to

adhere as much as possible to the religious beliefs and rituals of their

African ancestors. Missionaries working in the South were especially

displeased with slave retention of African practices such as polygamy

and what they called idolatrous dancing. In fact, even blacks who

embraced Christianity in America did not completely abandon Old World

religion. Instead, they engaged in syncretism, blending Christian

influences with traditional African rites and beliefs. Symbols and

objects, such as crosses, were conflated with charms carried by Africans

to ward off evil spirits. Christ was interpreted as a healer similar to

the priests of Africa. In the New World, fusions of African

spirituality and Christianity led to distinct new practices among slave

populations, including voodoo or vodun in Haiti and Spanish Louisiana.

Although African religious influences were also important among Northern

blacks, exposure to Old World religions was more intense in the South,

where the density of the black population was greater.

There were, however, some commonalities across the majority of

tribal traditions. Perhaps the primary understanding of tribal

traditions was that there was not a separation of the sacred and the

secular.

All life was sacred and the supernatural was present in every facet

and focus of life. Most tribal traditions highlighted this experience of

the supernatural in ecstatic experiences of the supernatural brought on

by ritual song and dance. Repetitious music and dancing were often used

to bring on these experiences through the use of drums and chanting.

The realization of these experiences was in the "possession" of a

worshipper in which one not only is taken over by the divine but

actually becomes one with the divine.

Echoes of African tribal traditions can be seen in the

Christianity practiced by slaves in the Americas. The song, dance, and

ecstatic experiences of traditional tribal religion were Christianized

and practiced by slaves in what is called the "Ring Shout." This practice was a major mark of African American Christianity during the slavery period.

Christianity came more slowly to the slaves of North America.

Many colonial slaveholders feared that baptizing slaves would lead to

emancipation because of vague laws concerning the slave status of

Christians under British colonial rule. Even after 1706, by which time

many states had passed laws stating that baptism would not alter slave

status, slaveholders were worried that the catechization of slaves

wouldn't be a wise economic choice. Slaves usually had one day off each

week, usually Sunday. That time was used to grow their own crops, as

well as dancing and singing (doing such things on the Sabbath was

frowned on by most preachers), so there was little time for slaves to

receive religious instruction.

During the antebellum period, slave preachers - enslaved or

formally enslaved evangelists - became instrumental in shaping slave

Christianity. They preached a gospel radically different from that of

white preachers, who often used Christianity in an attempt to make

slaves more complacent to their enslaved status. Rather than focusing on

obedience, slave preachers placed a greater emphasis on the Old

Testament, especially the book of Exodus. They likened the plight of the

American slaves to the enslaved Hebrews of the Bible, instilling hope

into the hearts of those enslaved. Slave preachers were instrumental in

shaping the religious landscape of African Americans for decades to

come.

Islam

According to Bernard Lewis,

slavery has been a part of Islam's history from its beginning. The

Quran like the Old and the New Testaments, states Lewis, "assumes the

existence of slavery". It attempts to regulate slavery and thereby implicitly accepts it. Muhammad and his Companions owned slaves, and some of them acquired slaves through conquests.

The Quran does not forbid slavery, nor does it consider it as a permanent institution. In various verses, it refers to slaves as "necks" (raqabah) or "those whom your right hand possesses" (Ma malakat aymanukum). In addition to these terms for slaves, the Quran and early Islamic literature uses 'Abd (male) and Amah

(female) term for an enslaved and servile possession, as well as other

terms. According to Brockopp, seven separate terms for slaves appear in

the Quran, in at least twenty nine Quranic verses.

The Quran assigns the same spiritual value to a slave as to a free man, and a believing slave is regarded as superior to a free pagan or idolator.

The manumission of slaves is regarded as a meritorious act in the

Quran, and is recommended either as an act of charity or as expiation

for sins.

While the spiritual value of a slave was same as the freeman, states

Forough Jahanbakhsh, in regards to earthly matters, a slave was not an

equal to the freeman and relegated to an inferior status.

In Quran and for its many commentators, states Ennaji, there is a

fundamental distinction between free Muslims and slaves, a basic

constituent of its social organization, an irreparable dichotomy

introduced by the existence of believers and infidels.

The corpus of hadith attributed to Muhammad or his Companions contains a large store of reports enjoining kindness toward slaves. Chouki El Hamel has argued that the Quran recommends gradual abolition of slavery, and that some hadith are consistent with that message while others contradict it.

According to Dror Ze'evi, early Islamic dogma set out to improve

conditions of human bondage. It forbade enslavement of free members of

Islamic society, including non-Muslims (dhimmis)

residing under Islamic rule. Islam also allowed the acquisition of

lawful non-Muslim slaves who were imprisoned, slaves purchased from

lands outside the Islamic state, as well as considered the boys or girls

born to slaves as slaves. Islamic law treats a free man and a slave unequally in sentencing for an equivalent crime.

For example, traditional Sunni jurisprudence, with the exception of

Hanafi law, objects to putting a free man to death for killing a slave.

A slave who commits a crime may receive the same punishment as a free

man, a punishment half as severe, or the master may be responsible for

paying the damages, depending on the crime.

According to Ze'evi, Islam considered the master to own the slave's

labor, a slave to be his master's property to be sold or bought at will,

and that the master was entitled to slave's sexual submission.

The Islamic law (sharia) allows the taking of infidels (non-Muslims) as slaves, during religious wars also called holy wars or jihad. In the early Islamic communities, according to Kecia Ali, "both life and law were saturated with slaves and slavery".

War, tribute from vassal states, purchase and children who inherited

their parent's slavery were the sources of slaves in Islam. In Islam, according to Paul Lovejoy,

"the religious requirement that new slaves be pagans and need for

continued imports to maintain slave population made Africa an important

source of slaves for the Islamic world."

Slavery of non-Muslims, followed by the structured process of

converting them to Islam then encouraging the freeing of the converted

slave, states Lovejoy helped the growth of Islam after its conquests.

According to Mohammed Ennaji, the ownership gave the master a right "to punish one's slave". In Islam, a child inherited slavery if he or she was born to a slave mother and slave father.

However, if the child was born to a slave mother and her owner master,

then the child was free. Slaves could be given as property (dower)

during marriage. The text encourages Muslim men to take slave women as sexual partners (concubines), or marry them. Islam, states Lewis, did not permit Dhimmis

(non-Muslims) "to own Muslim slaves; and if a slave owned by a dhimmi

embraced Islam, his owner was legally obliged to free or sell him".

There was also a gradation in the status on the slave, and his

descendants, after the slave converted to Islam.

Under Islamic law, in "what might be called civil matters", a

slave was "a chattel with no legal powers or rights whatsoever", states

Lewis. A slave could not own or inherit property or enter into a

contract. However, he was better off in terms of rights than Greek or

Roman slaves.

According to Chirag Ali, the early Muhammadans misinterpreted the Quran

as sanctioning "polygamy, arbitrary divorce, slavery, concubinage and

religious wars", and he states that the Quranic injunctions are against

all this. According to Ron Shaham and other scholars, the various jurisprudence systems on Sharia such as Maliki, Hanafi, Shafi'i, Hanbali and others differ in their interpretation of the Islamic law on slaves.

Slaves were particularly numerous in Muslim armies. Slave armies

were deployed by Sultans and Caliphs at various medieval era war fronts

across the Islamic Empires, playing an important role in the expansion of Islam in Africa and elsewhere. Slavery of men and women in Islamic states such as the Ottoman Empire, states Ze'evi, continued through the early 20th-century.

Bahá'í Faith

Bahá'u'lláh, founder of the Bahá'í Faith, commended Queen Victoria for abolishing the slave trade in a letter written to Her Majesty between 1868-1872. Bahá'u'lláh also forbids slavery in the Kitáb-i-Aqdas

written around 1873 considered by Bahá'ís to be the holiest book

revealed by Bahá'u'lláh in which he states, "It is forbidden you to

trade in slaves, be they men or women."

Both the Báb and Bahá'u'lláh owned slaves of African descent

before the writing of the Kitab-i-Aqdas. While the Báb purchased

several slaves, Bahá'u'lláh acquired his through inheritance and freed

them. Bahá'u'lláh officially condemned slavery in 1874. 21st century

scholarship has found that the Báb credited one of the slaves of his

elders as having raised him and compares him favorably with his own

father.

Work has continued on other recent finds in archives such as a very

early document of Bahá'u'lláh's explaining his emancipating his slave

because as all humans are symbolically slaves of God none can be owned

by another saying "How, then, can this thrall claim for himself ownership of any other human being? Nay,…."

Hinduism

Hindu Vedas regard liberation to be the ultimate goal which is contrary to slavery. Hindu Smritis condemn slavery.

The term "dasa" (dāsa) in ancient Hindu text is loosely translated as "slave."

However, the meaning of the term varied over time. R. S. Sharma, in his

1958 book, for example, states that the only word which could possibly

mean slave in Rigveda is dāsa, and this sense of use is traceable to

four later verses in Rigveda.

The term dāsa in the Rigveda, has been also been translated as a

servant or enemy, and the identity of this term remains unclear and

disputed among scholars.

The word dāsi is found in Rigveda and Atharvaveda, states R.S. Sharma, which he states represented "a small servile class of women slaves". Slavery in Vedic period, according to him, was mostly confined to women employed as domestic workers. He translates dasi in a Vedic era Upanishad as "maid-servant". Male slaves are rarely mentioned in the Vedic texts. The word dāsa occurs in the Hindu Sruti texts Aitareya and Gopatha Brahmanas, but not in the sense of a slave.

Towards the end of the Vedic period (600 BCE), a new system of varnas had appeared, with people called shudras replacing the erstwhile dasas. Some of the shudras were employed as labouring masses on farm land, much like "helots of Sparta", even though they were not treated with the same degree of coercion and contempt. They could be given away as gifts along with the land, which came in for criticism from the religious texts Āśvalāyana and Kātyāyana Śrautasūtras. The term dasa was now employed to designate such enslaved people.

Slavery arose out of debt, sale by parents or oneself (due to famines),

judicial decree or fear. The slaves were differentiated by origin and

different disabilities and rules for manumission applied. While this

could happen to a person of any varna, shudras were much more likely to be reduced to slavery.

The Arthashastra laid down norms for the State to resettle shudra cultivators into new villages and providing them with land, grain, cattle and money. It also stated that aryas could not be subject to slavery and that the selling or mortgaging of a shudra was punishable unless he was a born slave.

Buddhism

In Pali language Buddhist texts, Amaya-dasa has been translated by Davids and Stede in 1925, as a "slave by birth", Kila-dasa translated as a "bought slave", and Amata-dasa as "one who sees Amata (Sanskrit: Amrita, nectar of immortality) or Nibbana". However, dasa in ancient texts can also mean "servant".

Words related to dasa are found in early Buddhist texts, such as dāso na pabbājetabbo, which Davids and Stede translate as "the slave cannot become a Bhikkhu". This restriction on who could become a Buddhist monk is found in Vinaya Pitakam i.93, Digha Nikaya, Majjhima Nikāya, Tibetan Bhiksukarmavakya and Upasampadajnapti. Schopen states that this translation of dasa as slave is disputed by scholars.

Early Buddhist texts in Pali, according to R. S. Sharma, mention dāsa and kammakaras,

and they show that those who failed to pay their debts were enslaved,

and Buddhism did not allow debtors and slaves to join their monasteries.

The Buddhist Emperor Ashoka banned slavery and renounced war.