In narratology and comparative mythology, the monomyth, or the hero's journey, is the common template of a broad category of tales and lore that involves a hero who goes on an adventure, and in a decisive crisis wins a victory, and then comes home changed or transformed.

The study of hero myth narratives started in 1871 with anthropologist Edward Burnett Tylor's observations of common patterns in plots of heroes' journeys. Later on, others introduced various theories on hero myth narratives such as Otto Rank and his Freudian psychoanalytic approach to myth, Lord Raglan's unification of myth and rituals, and eventually hero myth pattern studies were popularized by Joseph Campbell, who was influenced by Carl Jung's view of myth. In his 1949 work The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Campbell described the basic narrative pattern as follows:

The study of hero myth narratives started in 1871 with anthropologist Edward Burnett Tylor's observations of common patterns in plots of heroes' journeys. Later on, others introduced various theories on hero myth narratives such as Otto Rank and his Freudian psychoanalytic approach to myth, Lord Raglan's unification of myth and rituals, and eventually hero myth pattern studies were popularized by Joseph Campbell, who was influenced by Carl Jung's view of myth. In his 1949 work The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Campbell described the basic narrative pattern as follows:

A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.Campbell and other scholars, such as Erich Neumann, describe narratives of Gautama Buddha, Moses, and Christ in terms of the monomyth. While others, such as Otto Rank and Lord Raglan, describe hero narrative patterns in terms of Freudian psychoanalysis and ritualistic senses. Critics argue that the concept is too broad or general to be of much usefulness in comparative mythology. Others say that the hero's journey is only a part of the monomyth; the other part is a sort of different form, or color, of the hero's journey.

Terminology

Campbell borrowed the word monomyth from Joyce's Finnegans Wake (1939). Campbell was a notable scholar of James Joyce's work and in A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake (1944) co-authored the seminal analysis of Joyce's final novel.

Campbell's singular the monomyth implies that the "hero's journey" is the ultimate narrative archetype, but the term monomyth has occasionally been used more generally, as a term for a mythological archetype or a supposed mytheme that re-occurs throughout the world's cultures.

Omry Ronen referred to Vyacheslav Ivanov's treatment of Dionysus as an "avatar of Christ" (1904) as

"Ivanov's monomyth".

The phrase "the hero's journey", used in reference to Campbell's

monomyth, first entered into popular discourse through two

documentaries. The first, released in 1987, The Hero's Journey: The World of Joseph Campbell, was accompanied by a 1990 companion book, The Hero's Journey: Joseph Campbell on His Life and Work (with Phil Cousineau and Stuart Brown, eds.).

The second was Bill Moyers's series of seminal interviews with Campbell, released in 1988 as the documentary (and companion book) The Power of Myth. Cousineau in the introduction to the revised edition of The Hero's Journey wrote "the monomyth is in effect a metamyth, a philosophical reading of the unity of mankind's spiritual history, the Story behind the story".

Summary

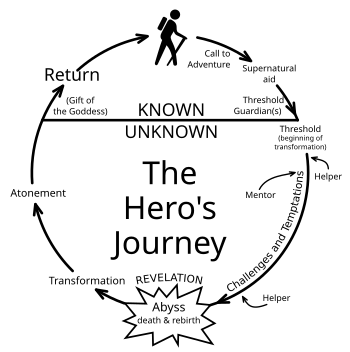

Campbell

describes 17 stages of the monomyth. Not all monomyths necessarily

contain all 17 stages explicitly; some myths may focus on only one of

the stages, while others may deal with the stages in a somewhat

different order. In the terminology of Claude Lévi-Strauss, the stages are the individual mythemes which are "bundled" or assembled into the structure of the monomyth.

The 17 stages may be organized in a number of ways, including division into three "acts" or sections:

- Departure (also Separation),

- Initiation (sometimes subdivided into IIA. Descent and IIB. Initiation) and

- Return.

In the departure part of the narrative, the hero or protagonist

lives in the ordinary world and receives a call to go on an adventure.

The hero is reluctant to follow the call, but is helped by a mentor figure.

The initiation section begins with the hero then

traversing the threshold to the unknown or "special world", where he

faces tasks or trials, either alone or with the assistance of helpers.

The hero eventually reaches "the innermost cave" or the central

crisis of his adventure, where he must undergo "the ordeal" where he

overcomes the main obstacle or enemy, undergoing "apotheosis" and gaining his reward (a treasure or "elixir").

The hero must then return to the ordinary world with his reward.

He may be pursued by the guardians of the special world, or he may be

reluctant to return, and may be rescued or forced to return by

intervention from the outside.

In the return section, the hero again traverses the

threshold between the worlds, returning to the ordinary world with the

treasure or elixir he gained, which he may now use for the benefit of

his fellow man. The hero himself is transformed by the adventure and

gains wisdom or spiritual power over both worlds.

Campbell's approach has been very widely received in narratology, mythography and psychotherapy,

especially since the 1980s, and a number of variant summaries of the

basic structure have been published. The general structure of Campbell's

exposition has been noted before and described in similar terms in

comparative mythology of the 19th and early 20th century, notably by

Russian folklorist Vladimir Propp who divided the structure of Russian folk tales into 31 "functions".

| Act | Campbell (1949) | David Adams Leeming (1981) | Phil Cousineau (1990) | Christopher Vogler (2007) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. Departure |

|

|

|

|

| II. Initiation |

|

|

|

|

| III. Return |

|

|

|

|

Campbell's seventeen stages

The following is a more detailed account of Campbell's original 1949 exposition of the monomyth in 17 stages.

Departure

The Call to Adventure

The hero begins in a situation of normality from which some information

is received that acts as a call to head off into the unknown.

Campbell: "...(the call of adventure is to) a forest, a kingdom underground, beneath the waves, or above the sky, a secret island, lofty mountaintop, or profound dream state; but it is always a place of strangely fluid and polymorphous beings, unimaginable torments, super human deeds, and impossible delight. The hero can go forth of his own volition to accomplish the adventure, as did Theseus when he arrived in his father's city, Athens, and heard the horrible history of the Minotaur; or he may be carried or sent abroad by some benign or malignant agent as was Odysseus, driven about the Mediterranean by the winds of the angered god, Poseidon. The adventure may begin as a mere blunder... or still again, one may be only casually strolling when some passing phenomenon catches the wandering eye and lures one away from the frequented paths of man. Examples might be multiplied, ad infinitum, from every corner of the world."

Refusal of the Call

Often when the call is given, the future hero first refuses to heed it.

This may be from a sense of duty or obligation, fear, insecurity, a

sense of inadequacy, or any of a range of reasons that work to hold the

person in his current circumstances.

Campbell: "Refusal of the summons converts the adventure into its negative. Walled in boredom, hard work, or 'culture,' the subject loses the power of significant affirmative action and becomes a victim to be saved. His flowering world becomes a wasteland of dry stones and his life feels meaningless—even though, like King Minos, he may through titanic effort succeed in building an empire or renown. Whatever house he builds, it will be a house of death: a labyrinth of cyclopean walls to hide from him his minotaur. All he can do is create new problems for himself and await the gradual approach of his disintegration."

Meeting the Mentor

Once the hero has committed to the quest, consciously or unconsciously,

his guide and magical helper appears or becomes known. More often than

not, this supernatural mentor will present the hero with one or more

talismans or artifacts that will aid him later in his quest. Meeting the

person that can help them in their journey.

Campbell: "For those who have not refused the call, the first encounter of the hero journey is with a protective figure (often a little old crone or old man) who provides the adventurer with amulets against the dragon forces he is about to pass. What such a figure represents is the benign, protecting power of destiny. The fantasy is a reassurance—promise that the peace of Paradise, which was known first within the mother womb, is not to be lost; that it supports the present and stands in the future as well as in the past (is omega as well as alpha); that though omnipotence may seem to be endangered by the threshold passages and life awakenings, protective power is always and ever present within or just behind the unfamiliar features of the world. One has only to know and trust, and the ageless guardians will appear. Having responded to his own call, and continuing to follow courageously as the consequences unfold, the hero finds all the forces of the unconscious at his side. Mother Nature herself supports the mighty task. And in so far as the hero's act coincides with that for which his society is ready, he seems to ride on the great rhythm of the historical process."

Crossing the First Threshold

This is the point where the hero actually crosses into the field of

adventure, leaving the known limits of his world and venturing into an

unknown and dangerous realm where the rules and limits are unknown.

Campbell: "With the personifications of his destiny to guide and aid him, the hero goes forward in his adventure until he comes to the 'threshold guardian' at the entrance to the zone of magnified power. Such custodians bound the world in four directions—also up and down—standing for the limits of the hero's present sphere, or life horizon. Beyond them is darkness, the unknown and danger; just as beyond the parental watch is danger to the infant and beyond the protection of his society danger to the members of the tribe. The usual person is more than content, he is even proud, to remain within the indicated bounds, and popular belief gives him every reason to fear so much as the first step into the unexplored. The adventure is always and everywhere a passage beyond the veil of the known into the unknown; the powers that watch at the boundary are dangerous; to deal with them is risky; yet for anyone with competence and courage the danger fades."

Belly of the Whale

The belly of the whale represents the final separation from the hero's

known world and self. By entering this stage, the person shows

willingness to undergo a metamorphosis. When first entering the stage

the hero may encounter a minor danger or set back.

Campbell: "The idea that the passage of the magical threshold is a transit into a sphere of rebirth is symbolized in the worldwide womb image of the belly of the whale. The hero, instead of conquering or conciliating the power of the threshold, is swallowed into the unknown and would appear to have died. This popular motif gives emphasis to the lesson that the passage of the threshold is a form of self-annihilation. Instead of passing outward, beyond the confines of the visible world, the hero goes inward, to be born again. The disappearance corresponds to the passing of a worshipper into a temple—where he is to be quickened by the recollection of who and what he is, namely dust and ashes unless immortal. The temple interior, the belly of the whale, and the heavenly land beyond, above, and below the confines of the world, are one and the same. That is why the approaches and entrances to temples are flanked and defended by colossal gargoyles: dragons, lions, devil-slayers with drawn swords, resentful dwarfs, winged bulls. The devotee at the moment of entry into a temple undergoes a metamorphosis. Once inside he may be said to have died to time and returned to the World Womb, the World Navel, the Earthly Paradise. Allegorically, then, the passage into a temple and the hero-dive through the jaws of the whale are identical adventures, both denoting in picture language, the life-centering, life-renewing act."

Initiation

The Road of Trials

The road of trials is a series of tests that the hero must undergo to

begin the transformation. Often the hero fails one or more of these

tests, which often occur in threes. Eventually the hero will overcome

these trials and move on to the next step.

Campbell: "Once having traversed the threshold, the hero moves in a dream landscape of curiously fluid, ambiguous forms, where he must survive a succession of trials. This is a favorite phase of the myth-adventure. It has produced a world literature of miraculous tests and ordeals. The hero is covertly aided by the advice, amulets, and secret agents of the supernatural helper whom he met before his entrance into this region. Or it may be that he here discovers for the first time that there is a benign power everywhere supporting him in his superhuman passage. The original departure into the land of trials represented only the beginning of the long and really perilous path of initiatory conquests and moments of illumination. Dragons have now to be slain and surprising barriers passed—again, again, and again. Meanwhile there will be a multitude of preliminary victories, unsustainable ecstasies and momentary glimpses of the wonderful land."

The Meeting with the Goddess

This is where the hero gains items given to him that will help him in the future.

Campbell: "The ultimate adventure, when all the barriers and ogres have been overcome, is commonly represented as a mystical marriage of the triumphant hero-soul with the Queen Goddess of the World. This is the crisis at the nadir, the zenith, or at the uttermost edge of the earth, at the central point of the cosmos, in the tabernacle of the temple, or within the darkness of the deepest chamber of the heart. The meeting with the goddess (who is incarnate in every woman) is the final test of the talent of the hero to win the boon of love (charity: amor fati), which is life itself enjoyed as the encasement of eternity. And when the adventurer, in this context, is not a youth but a maid, she is the one who, by her qualities, her beauty, or her yearning, is fit to become the consort of an immortal. Then the heavenly husband descends to her and conducts her to his bed—whether she will or not. And if she has shunned him, the scales fall from her eyes; if she has sought him, her desire finds its peace."

The Woman As Temptress

In this step, the hero faces those temptations, often of a physical or

pleasurable nature, that may lead him to abandon or stray from his

quest, which does not necessarily have to be represented by a woman.

Woman is a metaphor for the physical or material temptations of life,

since the hero-knight was often tempted by lust from his spiritual

journey.

Campbell: "The crux of the curious difficulty lies in the fact that our conscious views of what life ought to be seldom correspond to what life really is. Generally we refuse to admit within ourselves, or within our friends, the fullness of that pushing, self-protective, malodorous, carnivorous, lecherous fever which is the very nature of the organic cell. Rather, we tend to perfume, whitewash, and reinterpret; meanwhile imagining that all the flies in the ointment, all the hairs in the soup, are the faults of some unpleasant someone else. But when it suddenly dawns on us, or is forced to our attention that everything we think or do is necessarily tainted with the odor of the flesh, then, not uncommonly, there is experienced a moment of revulsion: life, the acts of life, the organs of life, woman in particular as the great symbol of life, become intolerable to the pure, the pure, pure soul. The seeker of the life beyond life must press beyond (the woman), surpass the temptations of her call, and soar to the immaculate ether beyond."

Atonement with the Father/Abyss

In this step the hero must confront and be initiated by whatever holds

the ultimate power in his life. In many myths and stories this is the

father, or a father figure who has life and death power. This is the

center point of the journey. All the previous steps have been moving

into this place, all that follow will move out from it. Although this

step is most frequently symbolized by an encounter with a male entity,

it does not have to be a male; just someone or thing with incredible

power.

Campbell: "Atonement consists in no more than the abandonment of that self-generated double monster—the dragon thought to be God (superego) and the dragon thought to be Sin (repressed id). But this requires an abandonment of the attachment to ego itself, and that is what is difficult. One must have a faith that the father is merciful, and then a reliance on that mercy. Therewith, the center of belief is transferred outside of the bedeviling god's tight scaly ring, and the dreadful ogres dissolve. It is in this ordeal that the hero may derive hope and assurance from the helpful female figure, by whose magic (pollen charms or power of intercession) he is protected through all the frightening experiences of the father's ego-shattering initiation. For if it is impossible to trust the terrifying father-face, then one's faith must be centered elsewhere (Spider Woman, Blessed Mother); and with that reliance for support, one endures the crisis—only to find, in the end, that the father and mother reflect each other, and are in essence the same. The problem of the hero going to meet the father is to open his soul beyond terror to such a degree that he will be ripe to understand how the sickening and insane tragedies of this vast and ruthless cosmos are completely validated in the majesty of Being. The hero transcends life with its peculiar blind spot and for a moment rises to a glimpse of the source. He beholds the face of the father, understands—and the two are atoned."

Apotheosis

This is the point of realization in which a greater understanding is

achieved. Armed with this new knowledge and perception, the hero is

resolved and ready for the more difficult part of the adventure.

Campbell: "Those who know, not only that the Everlasting lies in them, but that what they, and all things, really are is the Everlasting, dwell in the groves of the wish fulfilling trees, drink the brew of immortality, and listen everywhere to the unheard music of eternal concord."

The Ultimate Boon

The ultimate boon is the achievement of the goal of the quest. It is

what the hero went on the journey to get. All the previous steps serve

to prepare and purify the hero for this step, since in many myths the

boon is something transcendent like the elixir of life itself, or a

plant that supplies immortality, or the holy grail.

Campbell: "The gods and goddesses then are to be understood as embodiments and custodians of the elixir of Imperishable Being but not themselves the Ultimate in its primary state. What the hero seeks through his intercourse with them is therefore not finally themselves, but their grace, i.e., the power of their sustaining substance. This miraculous energy-substance and this alone is the Imperishable; the names and forms of the deities who everywhere embody, dispense, and represent it come and go. This is the miraculous energy of the thunderbolts of Zeus, Yahweh, and the Supreme Buddha, the fertility of the rain of Viracocha, the virtue announced by the bell rung in the Mass at the consecration, and the light of the ultimate illumination of the saint and sage. Its guardians dare release it only to the duly proven."

Return

Refusal of the Return

Having found bliss and enlightenment in the other world, the hero may

not want to return to the ordinary world to bestow the boon onto his

fellow man.

Campbell: "When the hero-quest has been accomplished, through penetration to the source, or through the grace of some male or female, human or animal, personification, the adventurer still must return with his life-transmuting trophy. The full round, the norm of the monomyth, requires that the hero shall now begin the labor of bringing the runes of wisdom, the Golden Fleece, or his sleeping princess, back into the kingdom of humanity, where the boon may redound to the renewing of the community, the nation, the planet or the ten thousand worlds. But the responsibility has been frequently refused. Even Gautama Buddha, after his triumph, doubted whether the message of realization could be communicated, and saints are reported to have died while in the supernal ecstasy. Numerous indeed are the heroes fabled to have taken up residence forever in the blessed isle of the unaging Goddess of Immortal Being."

The Magic Flight

Sometimes the hero must escape with the boon, if it is something that

the gods have been jealously guarding. It can be just as adventurous and

dangerous returning from the journey as it was to go on it.

Campbell: "If the hero in his triumph wins the blessing of the goddess or the god and is then explicitly commissioned to return to the world with some elixir for the restoration of society, the final stage of his adventure is supported by all the powers of his supernatural patron. On the other hand, if the trophy has been attained against the opposition of its guardian, or if the hero's wish to return to the world has been resented by the gods or demons, then the last stage of the mythological round becomes a lively, often comical, pursuit. This flight may be complicated by marvels of magical obstruction and evasion."

Rescue from Without

Just as the hero may need guides and assistants to set out on the quest,

often he must have powerful guides and rescuers to bring them back to

everyday life, especially if the person has been wounded or weakened by

the experience.

Campbell: "The hero may have to be brought back from his supernatural adventure by assistance from without. That is to say, the world may have to come and get him. For the bliss of the deep abode is not lightly abandoned in favor of the self-scattering of the wakened state. 'Who having cast off the world,' we read, 'would desire to return again? He would be only there.' And yet, in so far as one is alive, life will call. Society is jealous of those who remain away from it, and will come knocking at the door. If the hero... is unwilling, the disturber suffers an ugly shock; but on the other hand, if the summoned one is only delayed—sealed in by the beatitude of the state of perfect being (which resembles death)—an apparent rescue is effected, and the adventurer returns."

The Crossing of the Return Threshold

The trick in returning is to retain the wisdom gained on the quest, to

integrate that wisdom into a human life, and then maybe figure out how

to share the wisdom with the rest of the world.

Campbell: "The returning hero, to complete his adventure, must survive the impact of the world. Many failures attest to the difficulties of this life-affirmative threshold. The first problem of the returning hero is to accept as real, after an experience of the soul-satisfying vision of fulfillment, the passing joys and sorrows, banalities and noisy obscenities of life. Why re-enter such a world? Why attempt to make plausible, or even interesting, to men and women consumed with passion, the experience of transcendental bliss? As dreams that were momentous by night may seem simply silly in the light of day, so the poet and the prophet can discover themselves playing the idiot before a jury of sober eyes. The easy thing is to commit the whole community to the devil and retire again into the heavenly rock dwelling, close the door, and make it fast. But if some spiritual obstetrician has drawn the shimenawa across the retreat, then the work of representing eternity in time, and perceiving in time eternity, cannot be avoided" The hero returns to the world of common day and must accept it as real.

Master of Two Worlds

This step is usually represented by a transcendental hero like Jesus or

Gautama Buddha. For a human hero, it may mean achieving a balance

between the material and spiritual. The person has become comfortable

and competent in both the inner and outer worlds.

Campbell: "Freedom to pass back and forth across the world division, from the perspective of the apparitions of time to that of the causal deep and back—not contaminating the principles of the one with those of the other, yet permitting the mind to know the one by virtue of the other—is the talent of the master. The Cosmic Dancer, declares Nietzsche, does not rest heavily in a single spot, but gaily, lightly, turns and leaps from one position to another. It is possible to speak from only one point at a time, but that does not invalidate the insights of the rest. The individual, through prolonged psychological disciplines, gives up completely all attachment to his personal limitations, idiosyncrasies, hopes and fears, no longer resists the self-annihilation that is prerequisite to rebirth in the realization of truth, and so becomes ripe, at last, for the great at-one-ment. His personal ambitions being totally dissolved, he no longer tries to live but willingly relaxes to whatever may come to pass in him; he becomes, that is to say, an anonymity."

Freedom to Live

Mastery leads to freedom from the fear of death, which in turn is the freedom to live. This is sometimes referred to as living in the moment, neither anticipating the future nor regretting the past.

Campbell: "The hero is the champion of things becoming, not of things become, because he is. "Before Abraham was, I AM." He does not mistake apparent changelessness in time for the permanence of Being, nor is he fearful of the next moment (or of the 'other thing'), as destroying the permanent with its change. 'Nothing retains its own form; but Nature, the greater renewer, ever makes up forms from forms. Be sure that nothing perishes in the whole universe; it does but vary and renew its form.' Thus the next moment is permitted to come to pass."

In Popular Culture and Literature

The monomyth concept has been popular in American literary studies and writing guides since at least the 1970s.

Christopher Vogler, a Hollywood film producer and writer, created a 7-page company memo, A Practical Guide to The Hero With a Thousand Faces, based on Campbell's work. Vogler's memo was later developed into the late 1990s book, The Writer's Journey: Mythic Structure For Writers.

George Lucas' Star Wars (1977) was notably classified as monomyth almost as soon as it came out.

In addition to the extensive discussion between Campbell and Bill Moyers broadcast in 1988 on PBS as The Power of Myth (Filmed at "Skywalker Ranch"), on Campbell's influence on the Star Wars films, Lucas himself gave an extensive interview for the biography Joseph Campbell: A Fire in the Mind

(Larsen and Larsen, 2002, pages 541-543) on this topic. In this

interview, Lucas states that in the early 1970s after completing his

early film, American Graffiti,

"it came to me that there really was no modern use of mythology...so

that's when I started doing more strenuous research on fairy tales,

folklore and mythology, and I started reading Joe's books. Before that I

hadn't read any of Joe's books... It was very eerie because in reading The Hero with A Thousand Faces I began to realize that my first draft of Star Wars was following classical motifs" (p. 541).

Twelve years after the making of The Power of Myth, Moyers and Lucas met again for the 1999 interview, the Mythology of Star Wars with George Lucas & Bill Moyers, to further discuss the impact of Campbell's work on Lucas's films.

In addition, the National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution sponsored an exhibit during the late 1990s called Star Wars: The Magic of Myth which discussed the ways in which Campbell's work shaped the Star Wars films. A companion guide of the same name was published in 1997.

Numerous literary works of popular fiction have been identified as examples of the monomyth template, including

Spenser's The Fairie Queene,

Melville's Moby Dick,

Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre,

works by Charles Dickens, William Faulkner, Maugham, J. D. Salinger,

Ernest Hemingway,

Mark Twain,

W. B. Yeats, C. S. Lewis,

and J. R. R. Tolkien,

Seamus Heaney

and Stephen King, among many others.

Feminist Literature and Female Heroines within the Monomyth

Jane Eyre

Charlotte Brontë's

character Jane Eyre is an important figure in illustrating heroines and

their place within the Hero's Journey. Charlotte Brontë sought to craft

a unique female character that the term "Heroine" could fully

encompass. Jane Eyre is a Bildungsroman,

a coming-of-age story common in Victorian fiction, also referred to as

an apprenticeship novel, that show moral and psychological development

of the protagonist as they grow into adults.

Jane being a Middle-class Victorian woman would face entirely different

obstacles and conflict than her male counterparts of this era such as

Pip in Great Expectations.

This would change the course of the Hero’s Journey as Bronte was able

to recognize the fundamental conflict that plagued women of this time.

One main source of this conflict being women’s relationship with power

and wealth and often being distant from obtaining both. Charlotte Brontë takes Jane's character a step further by making her

more passionate and outspoken than other Victorian women of this time.

The abuse and psychological trauma Jane receives from the Reeds as a

child cause her to develop two central goals for her to complete her

heroine journey: A need to love and be loved and her need for liberty.

Jane accomplishes part of attaining liberty when she castigates Mrs.

Reed for treating her poorly as a child, obtaining the freedom of her

mind. As Jane grows throughout the novel she also becomes unwilling to

sacrifice one of her goals for the other. When Rochester, the temptress

in her journey, asks her to stay with him as her mistress she refuses as

it would jeopardize the freedom she struggled to obtain. She instead

returns after Rochester's wife passes away, when she becomes free to

marry him and able to achieve both of her goals and complete her role in

the Hero's Journey.

While the story ends with a marriage trope, Brontë has Jane return to

Rochester after several chances to grow allowing her to return as close

to equals as possible, while also having fleshed out her growth within the heroine's journey.

Since Jane is able to marry Rochester as an equal and through her own

means this makes Jane one of the most satisfying and fulfilling heroines

in literature and in the heroine's journey.

Psyche

The story Metamorphoses also known as The Golden Ass by Apuleius in 158 A.D. is one of the most enduring and retold myths involving the Hero's Journey. The tale of Cupid and Psyche is a frame tale, a story within a story and is one of the thirteen stories within Metamorphoses.

Use of the frame tale puts both the story teller and reader into the

novel as characters, which explores a main aspect of the hero's journey

due to it being a process of tradition where literature is written and

read. Cupid and Psyche's tale has become the most popular of Metamorphoses and has been retold many times with successful iterations dating as recently as 1956's Till We Have Faces by C.S. Lewis.

Much of the tale's captivation comes from the central heroine Psyche.

Psyche's place within the hero's journey is fascinating and complex as

it revolves around her characteristics of being a beautiful woman and

the conflict that arises from it. Psyche's beauty causes her to become

ostracized from society as no male suitors will ask to marry her as they

feel unworthy of her seemingly divine beauty and kind nature. Due to

this, Psyche's call to adventure is involuntary as her beauty enrages

the goddess Venus, which results in Psyche being banished from her home.

Part of what makes Psyche such a polarizing figure within the

heroine's journey is her nature and ability to triumph over the unfair

trials set upon her by Venus. Psyche is given four seemingly impossible

tasks by Venus in order to get her husband Cupid back: The Sorting of

the seeds, the fleecing of the golden rams, collecting a crystal jar

full of the water of death, and retrieving a beauty creme from Hades.

The last task is considered to be one of the most monumental and

memorable tasks ever to be taken on in the history of the heroine's

journey due to its difficulty. Yet, Psyche is able to achieve each task

and complete her ultimate goal of becoming an immortal goddess and

moving to Mount Olympus to be with her husband Cupid for all eternity.

During the early 19th century, a Norwegian version of the Psyche myth was collected in Finnmark by Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe, who are still considered to be Norway's answer to the Brothers Grimm. It was published in their legendary anthology Norwegian Folktales. The fairy tale is titled East o' the Sun and West o' the Moon.

Criticism

Scholars have questioned the validity or usefulness of the monomyth category.

According to Northup (2006), mainstream scholarship of

comparative mythology since Campbell has moved away from "highly general

and universal" categories in general.

This attitude is illustrated by e.g. Consentino (1998), who remarks "It

is just as important to stress differences as similarities, to avoid

creating a (Joseph) Campbell soup of myths that loses all local flavor."

Similarly, Ellwood (1999) stated "A tendency to think in generic terms

of people, races ... is undoubtedly the profoundest flaw in mythological

thinking."

Others have found the categories Campbell works with so vague as

to be meaningless, and lacking the support required of scholarly

argument: Crespi (1990), writing in response to Campbell's filmed

presentation of his model, characterized it as "unsatisfying from a

social science perspective. Campbell's ethnocentrism will raise

objections, and his analytic level is so abstract and devoid of

ethnographic context that myth loses the very meanings supposed to be

embedded in the 'hero.'"

In a similar vein, American philosopher John Shelton Lawrence and American religious scholar Robert Jewett have discussed an "American Monomyth" in many of their books, The American Monomyth, The Myth of the American Superhero (2002), and Captain America and the Crusade Against Evil: The Dilemma of Zealous Nationalism (2003). They present this as an American reaction to the Campbellian monomyth. The "American Monomyth" storyline is: A

community in a harmonious paradise is threatened by evil; normal

institutions fail to contend with this threat; a selfless superhero

emerges to renounce temptations and carry out the redemptive task; aided

by fate, his decisive victory restores the community to its

paradisiacal condition; the superhero then recedes into obscurity.

The monomyth has also been criticized for focusing on the masculine journey. The Heroine's Journey (1990) by Maureen Murdock and From Girl to Goddess: The Heroine's Journey through Myth and Legend

(2010), by Valerie Estelle Frankel, both set out what they consider the

steps of the female hero's journey, which is different from Campbell's

monomyth.

According to changingminds.org, "[Campbell's] much admired and

much-copied pattern has also been criticized as leading to 'safe'

moviemaking, in which writers use his structure as a template, thus

leading to 'boring' repeats, albeit in different clothes."

While Frank Herbert's Dune

(1965) on the surface appears to follow the monomyth, this was in fact

to subvert it and take a critical view, as the author said in 1979, "The

bottom line of the Dune trilogy is: beware of heroes. Much better [to] rely on your own judgment, and your own mistakes." He wrote in 1985, "Dune

was aimed at this whole idea of the infallible leader because my view

of history says that mistakes made by a leader (or made in a leader's

name) are amplified by the numbers who follow without question."

Science fiction author David Brin in a 1999 Salon

article criticized the monomyth template as supportive of "despotism

and tyranny", indicating that he thinks modern popular fiction should

strive to depart from it in order to support more progressivist values.

Other scholars on hero narrative patterns

In narratology and comparative mythology, others have proposed narrative patterns such as psychoanalyst Otto Rank in 1909 and anthropologist Lord Raglan in 1936. Both have lists of different cross-cultural traits often found in the accounts of heroes, including mythical heroes. According to Robert Segal, "The theories of Rank, Campbell, and Raglan typify the array of analyses of hero myths."

Self-help movement and therapy

Poet Robert Bly, Michael J. Meade, and others involved in the men's movement

have also applied and expanded the concepts of the hero's journey and

the monomyth as a metaphor for personal spiritual and psychological

growth, particularly in the mythopoetic men's movement.

Characteristic of the mythopoetic men's movement is a tendency to

retell fairy tales and engage in their exegesis as a tool for personal

insight. Using frequent references to archetypes as drawn from Jungian analytical psychology, the movement focuses on issues of gender role, gender identity and wellness for modern men. Advocates would often engage in storytelling with music, these acts being seen as a modern extension to a form of "new age shamanism" popularized by Michael Harner at approximately the same time.

Among its most famous advocates were the poet Robert Bly, whose book Iron John: A Book About Men was a best-seller, being an exegesis of the fairy tale "Iron John" by the Brothers Grimm.

The mythopoetic men's movement spawned a variety of groups and workshops, led by authors such as Bly and Robert L. Moore.

Some serious academic work came out of this movement, including the

creation of various magazines and non-profit organizations.